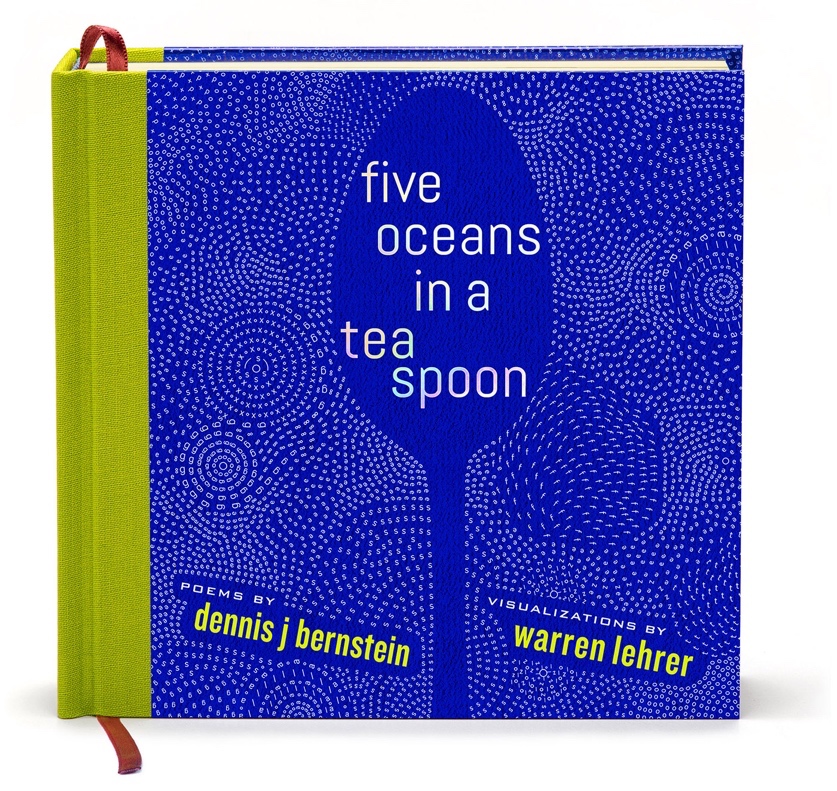

Here is the transcription of an extended conversation between multimedia artist and author Warren Lehrer and Brian Davis (a recent contemporary literature and poetics PhD grad from University of Maryland) that began in February 2020 at Lehrer’s studio in Queens, NY soon after the opening of the exhibition “Warren Lehrer: Books, Animation, Performance, Collaboration” at the Center for Book Arts in Manhattan. They discuss Lehrer’s recent book, Five Oceans in a Teaspoon (2019), a collection of visual poems written by Dennis J Bernstein, visualized by Lehrer, as well as Lehrer’s long running commitments to visual literature and collaborative art going back to the early 1980s. In addition to discussing several of Lehrer’s bookish projects, including his novel A Life in Books (2013), they discuss the different writing and printing technologies Lehrer has worked with and in over the years, as well as current issues in contemporary literature studies, such as documentary aesthetics, autofiction, and satire.

Brian: Five Oceans in a Teaspoon was recently published by Paper Crown Press and is the third book you and Dennis J Bernstein have collaborated on. Five Oceans is a collection of 225 short visual poems, written by Bernstein and visualized by yourself. Given that much of your previous work is also collaborative (e.g., Crossing the BLVD with Judith Sloan, The Search for It & Other Pronouns with Harvey Goldman, and of course the central protagonist in A Life in Books also does a lot of collaborative work), I thought we’d begin our conversation with collaboration. What was your and Bernstein’s process like for creating Five Oceans?

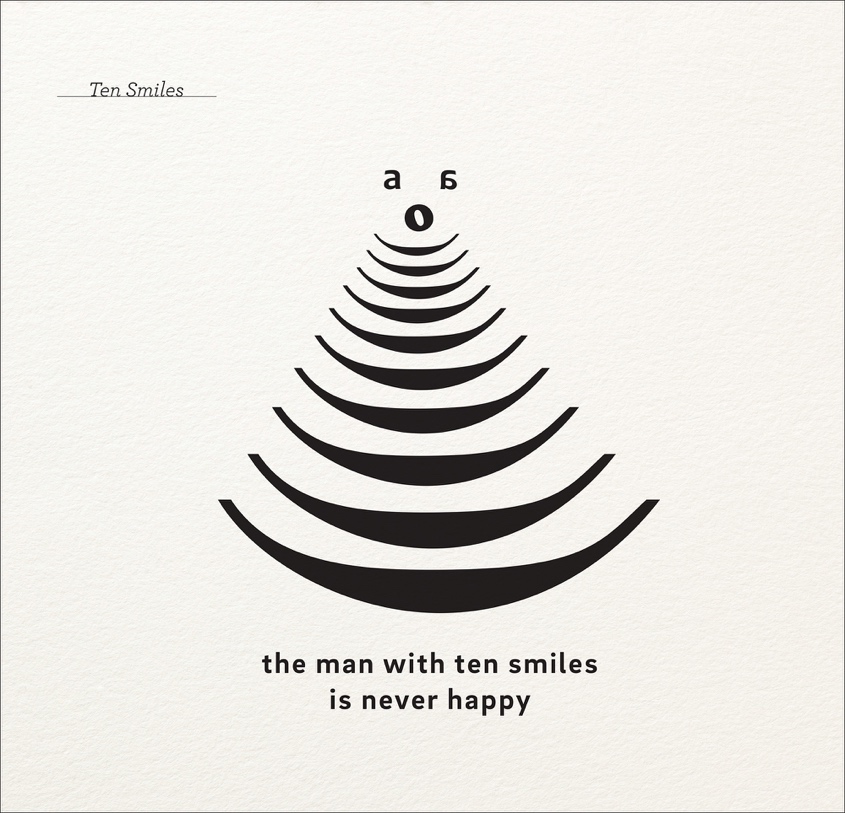

Warren: Well, I’m a workaholic. Or to put it more positively—I love doing my work. I love the process of writing and designing my self-authored books and projects. But I also love being with my friends. Looking back on it now I think one way I’ve sustained relationships with people I love is to collaborate with them. So I’m working and at the same time I'm with my friends, which is especially doable if I have very high regard for their creative work. Hence, Judith and I are married, we collaborate on projects together and started our nonprofit arts organization together (EarSay). And Dennis and I have been friends for four decades. We shared a house together when I was in college. I answered an ad that he placed looking for housemates and almost immediately I was struck by his poetry, especially his short poems which are exquisitely crafted, and sharp, and filled with rich content and often funny. Five Oceans in a Teaspoon began sort of by accident. I was touring with A Life in Books in San Francisco, staying at his and his girlfriend’s apartment there, and there was discussion about helping him with his next book. His previous collection of poems Special Ed, I edited and designed, but in a much more traditional way. I designed the cover and helped him structure the collection which features poems about teaching “special ed” kids in Far Rockaway. He started showing me these new poems he was writing in these small notebooks. He’s always carried notebooks around and is constantly writing poems. He’s the host and executive producer of a syndicated daily news radio program and ideas for poems can happen at any time, so the notebooks need to be portable. He said the larger page had become too frightening. It was less frightening to have smaller sized notebooks to write shorter poems. I noticed a poem in one of the notebooks called “ten smiles” that included a little doodle of ten smiles. For some reason I took out my laptop and began transcribing the poem and the doodle typographically making the smiles out of parenthetical brackets. He really liked it! So I took some of his other poems with me and on the plane started working on another one, and then another one. When I returned home to New York I emailed him the new compositions of his poems and he really loved what I was doing. Most of these poems don’t have visual cues, they’re written just as text, a few lines to a poem. In time we decided to do this book together as equal collaborators. It’s the first of my eleven books that I didn’t write or co-write.

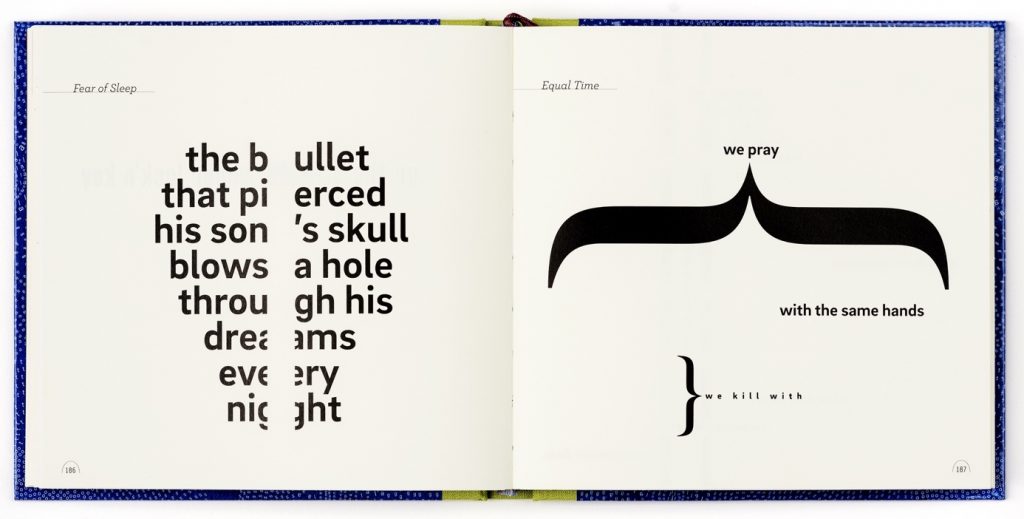

Brian: Most of these poems are only given the space of a single page, sometimes two, as is typical of concrete literature. They’re often anectodical, sometimes aphoristic, and sometimes they generate into short narrative poems. Each poem is also typographically different. Given that most of these poems do not possess a lot of narrativity, or “visual cues,” as you put it, how did you go about visualizing them?

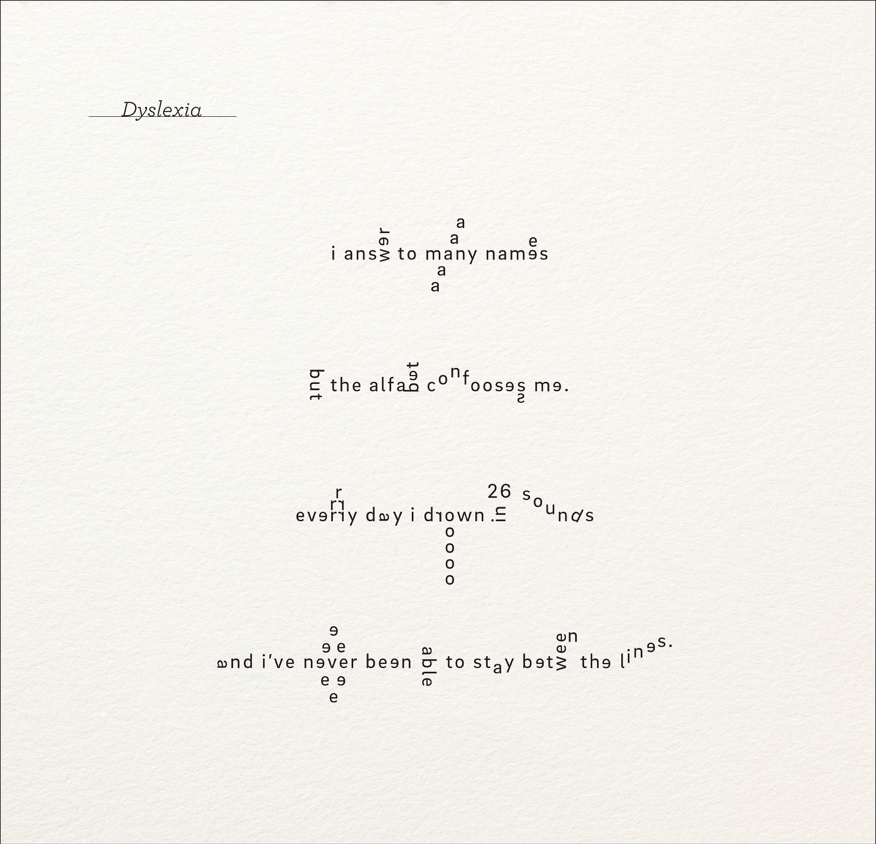

Warren: I let the writing take the lead, and I follow it. The ideas within the poem, its themes, metaphors, double meanings, ambiguities, subtexts, conflicts, voices, characters, structure, rhythmic cadences, underlying intent and emotional underpinnings were all grist for the mill. I work in a layout program, Adobe InDesign, and I go till I find the form for the poem. It could take 100 pages trying and trying, taking the last iteration of what I’ve done, copying it and pasting it in another page and tweaking it some more, trying this and that until something starts to happen. I think the very first poem in the book, “Dyslexia,” is a good starting point for what I was after. I wanted to get beyond the stereotype of dyslexia as just being about reading words backwards. Which is not all that is involved and everyone with dyslexia has a different experience. I talked with Dennis about his experience. So you have letters that are on the move, rotating up, flopped, moving diagonally and bouncing around. Part of what I’m after here is helping the reader not only read the text but have an experience of dyslexia.

Brian: Reading “Dyslexia,” like so many other poems in the collection, can be disorienting; readers must rotate the book in every which way in order to follow the movement of letters on the page. Because some of the letters in “Dyslexia” repeat or proliferate in various directions, the reading process slows down and the meaning-making process becomes a bit strenuous. What about line breaks and segmentation, though. To what extent did you maintain the prosody of the original poems?

Warren: I tried to adhere to Dennis’s line breaks, but he gave me a lot of liberties and he was accepting of new line breaks that I sometimes made. I would never break a line arbitrarily, even though it might not have been his line breaks. In the end, hopefully there is a grace to the final composition of each poem that does not reveal the struggle that it took me, or Dennis for that matter.

Brian: How many poems did the two of you work on that didn’t make it into the book?

Warren: I started with several thousand short poems by Dennis, mostly that had been typed up, not written by hand. We ended up with about 300 visualized poems, which got edited down to 225, and then I structured the book into eight movements that form a sort of narrative starting out with childhood and ending with more recent circumstances in Dennis’s life. It tells the arc of a life with all these other things in between like being a journalist, relationships, observing other peoples’ situations as well as his own. Cumulatively it forms a memoir in short visual poems.

Brian: There aren’t really any names in this book and there isn’t really any consistent voice or authorial point of view either. This takes me back to the point about the book’s minimal narrativity. To the extent this is a memoir, it’s highly fragmented, and the causal or thematic relationships that exist between and among poems is often obscure. Does this fragmentation and disjunction inform the book’s concept of the self and subjectivity? I’m also wondering to what extent this book is attempting a new take on what a memoir can be.

Warren: Yes. It’s fair to say that many of these poems are voice poems, some of the many voices one may encounter over the course of a life, as an observant poet, as a journalist, as a person reflecting on the smaller and larger aspects of existence. As compared with a more linear narrative that walks a reader through one event leading to another.

Brian: Five Oceans is also a multimedia project. The website for the book features short animations to individual poems that you created in Adobe After Effects, which are accompanied by original musical scores composed by Andrew Griffin. These animations perform the poems, as well as represent, in a sense, their process of creation. One of my favorite animations is the one for “Avowel,” one of the first epigrammatic poems in the book, which reads: “the alphabet is segregated with a small minority calling the shots”. Given the title and the arrangement of letters, this “small minority” obviously refers to English vowels. In the animation, the vowels are increasingly pronounced and isolated from the consonants which hang and swing from the vowels as if from a rope (an impression we don’t get from the printed version of the poem). The visualization gives the impression that vowels are superior to consonants, and the word “segregation” accompanied by the rope, at least in the U.S. context, brings to mind gruesome images of the Jim Crow south. There also seems to be some punning going on with the title. To “avow” is to confess openly, but given the language and imagery of segregation, the poem invites, to my thinking, associations with “disavowal” (the repudiation of morality, justice, etc.). Was this at all the intended effect of the poem and animation?

Warren: I love your interpretation. Let’s start with the printed version of the poem. When you first come upon this poem it isn’t necessarily easy to read. You don’t know what you’re looking at. It forces you to participate as an active reader to put it together, even though, in the end, it’s just a three line poem.

Brian: Like all great works of concrete literature—as well as graphic novels—the text teaches you how to read it if you give it a chance. There are stage directions, so to speak, built into the sequences.

Warren: Right, and while most of the impressions you had of the poem’s animation were intended, I can’t say that Dennis or I took the poem as far as the disavowal part. But one of the perks of collaboration is discovering things after the work is done. Dennis and I were talking over the phone one day after the book and animations were launched and he said that what I did with “Avowel,” both on the page and on the screen, really captures the dyslexic experience of having to wrestle letters and words down on the page and pull it altogether into meaning. This surprised me. There are other poems in the book, particularly in the first movement, that address dyslexia, but I hadn’t recognized this as a dyslexia poem. I saw it as a critique of culture, society, and racism, and yes, as vowels calling the shots, ruling the roost over the consonants, and yes, in the animation I was able to bring the strings to life in a way that I couldn’t on the page. On the page, the consonants feel more like marionettes tied to and controlled by the vowels. It’s more of a diagram about control. And you’re right, the words “segregation” and “minority” are no accident. Many of Dennis’s poems operate on a number of levels. This poem is about the alphabet, literally personifying letters and the experience of writing and reading with dyslexia. And also it’s about societal and historical domination and power. In the animation, the strings that connect the vowels to the consonants operate more like chains and/or ropes. It’s both a deadly serious yanking in the animation of these sentient consonants out from beyond the frame, like from another continent, and it’s also playful and suspenseful, like fishing. There’s something on the line that is resisting. Will it be able to avoid getting caught? Or if you’re thinking more from the perspective of the fisherman, will I be able to catch this subject? And yes, the pun is there in the title. Dennis is always playing with language and is also a sharp and informed critic of American history. Avowal is an affirmation and admission of the truth. Vow is there too—a solemn promise. And then there’s just a story about vowels. Of course, both Dennis and I studied Hebrew for our bar mitzvahs and consonants are the power players in Hebrew and vowels are treated more like accents. In some versions of Hebrew there are no vowels written at all. One could debate some of these truisms. Do the vowels call the shots or do consonants? But my job was to take his poems and find them a visual form.

Brian: It seems to me that the meaning packed into this poem, its affective power and connotations, would not be possible without the visualization or the animation. Some readers and critics have questioned the artistic or literary merit of visual literature, pointing to its hybridity and affinities with advertising as a kind of gimmick (e.g., Rigolot 1978; Hansen 2009). How do you respond to such criticisms?

Warren: It’s tiresome how conservative so many gatekeepers in the literary world are when it comes to visual form. For most of them, no matter how integral the visual composition is to the meaning and the reading experience, and how distinctive the approach, it will be described as a gimmick or derivative, stereotyped as Concrete Poetry

or relegated to a particular decade, or simply ignored because the writing takes on a visual form at all and is therefore weird

or experimental

and so discounted as worthy of consideration. Whereas texts, especially prose that is set in rectangular gray slabs of justified columns are never referred to by these critics or publishers or editors or professors as a derivative form. I teach Visual Literature, which spans centuries and many movements and individual efforts, and I believe it’s high time this vast field of literary production be taught as part of the literary canon, albeit one that overlaps with visual art, new media, semiotics and other areas.

Brian: How did Bernstein respond to your visualizations, which in a sense are translations or rewritings of his original poems? I’m also wondering, given your long history of collaboration, if either of your writing processes have changed over the years as a result of working together?

Warren: Through the years since Dennis and I have collaborated he’s said that working with me has changed the way he writes, and he tends to think more visually because of it. I feel fortunate because a lot of poets are not going to let some other person mess with their stuff like this. At times Dennis would say hey you went too far, or you can’t break that line there. So there’s definitely negotiation in certain instances. I respect what he’s trying to do, and sometimes I didn’t see the significance, mostly in terms of line breaks or sometimes I’ve missed a secondary or tertiary meaning. And I have learned a lot about writing from Dennis. I am generally a more is more writer. I’m more John Coltrane and he’s more Eric Satie. My writing is voluminous and expressionistic (a novel with 101 books within it, 1000+ page Portrait Series books, 400 page panorama about new immigrants in Queens, NY, etc.). Dennis’ compositions, especially these poems are very spare. Alice Walker said of his writing, Not-one-word-mislaid... Each word, each line, each thought has a weight, a texture, a surprise all its own.

I’ve learned a lot from interacting with his craft.

Brian: Do you think your visualizations constitute new poems, something different or other than the poems Bernstein originally delivered to you?

Warren: I would still say these are his poems, even though both of our names are on the cover of the book. The book is ours together. He wrote the poems. He has the copyright for each poem. We share a copyright of the book. My relationship to his poems is like a filmmaker’s relationship to a text he adapts to the screen, or like a choreographer's dance interpretation of a text. It’s a performance of these texts. I’m interested in the relationship between page and screen and performance and how literature can be manifest in these different ways.

Brian: I’m surprised you see your visualizations as still being Bernstein’s poems, even though the end result comes from a significant amount of interpretation and adaptation on your part. I would argue that what we have here is a 1+1=3 scenario, where your visualizations amount to something new, offering readers experiences and inviting responses that are not conceivable from the originals alone.

Warren: I’m good with that. The result of the best collaborations should be multiplication, not addition, with some degree of magic in there too.

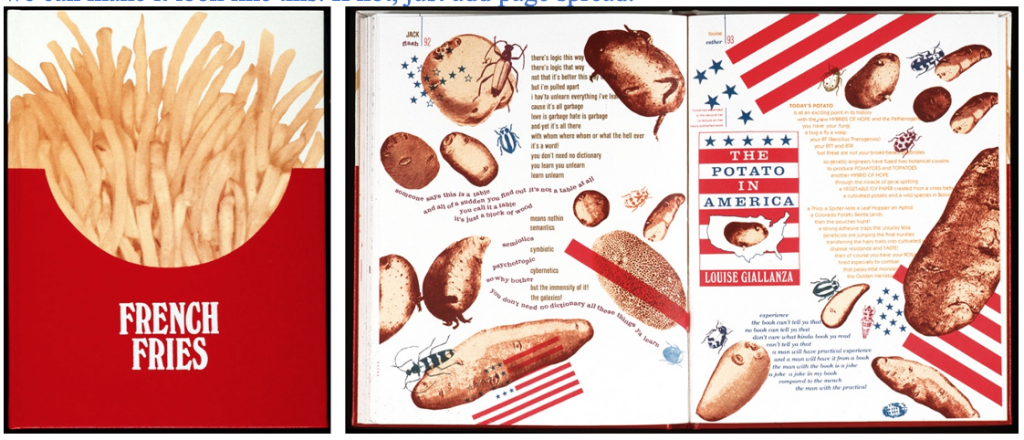

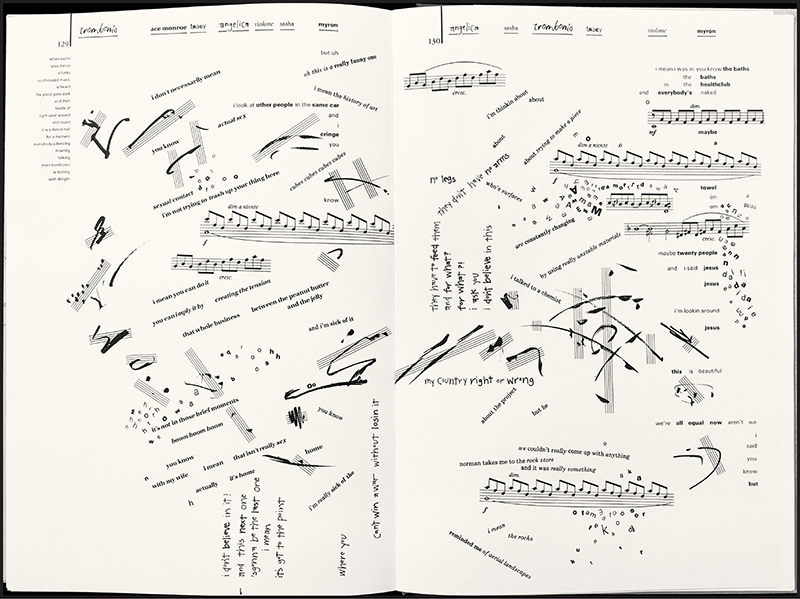

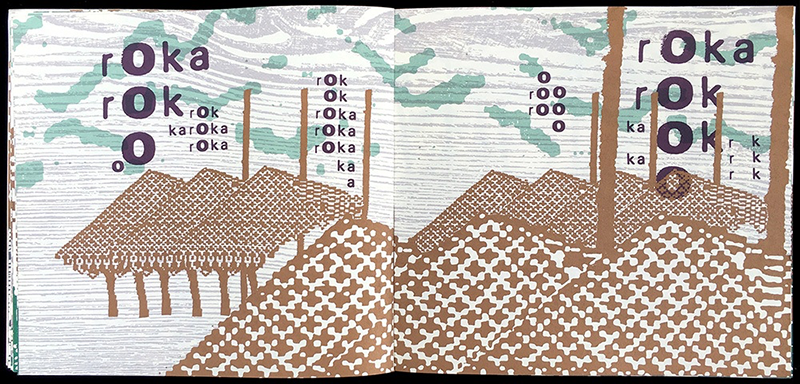

Brian: Before Five Oceans, you and Dennis collaborated on two books published by EarSay. In French Fries (1984), characters are inscribed in different fonts and colors, and in GRRRHHHH (1987), characters are also given distinctly different visual forms or identities. I was hoping you could talk about how you got into visual writing, as well as what interests you about the alphabet as both a writer/designer and a scholar.

Warren: Early on, my parents felt that I exhibited talent as a visual artist so they sent me to private art lessons in the basement of the Lutheran church in the town I grew up in from age six to eleven and then during school I remember having special permission to go to the easel in the back of the classroom to make paintings. So I’ve been making pictures from very early on. I got into writing early on too. Eventually I’m a fine art major—painting, printmaking, drawing—in college, but I’m writing poetry and short stories and for the school newspaper, mostly music reviews, sometimes reporting on events. At a certain point, letterforms and words started to make their way into my paintings and drawings. In 1975 or so, I brought a stack of drawings to a painting teacher of mine. He leafed through the stack, shook his head and said, “Warren, you’re a good student, but you’re barking up the wrong tree here. Words and images are two different languages and occupy two different parts of the brain. Don’t try to bring them together.” I left his office feeling like I had been given a mission in life and have been combining words and images in my work ever since, for better or worse, because to a certain extent his admonition was true. In many ways, writing and picture making had become separate. In the 1970s, in a fine art department, working words and language into printmaking and paintings was not something that was common. Looking back on it now, as someone who teaches visual literature and its history, I believe human language began with picture and writing as one and the same thing. Are cave paintings the beginning of writing or the beginning of picture making? Both fields lay claim to those early markings as part of their own origin stories. Then you get these writing systems that are iconographic. Eventually when the Phoneticians created a phonetic alphabetic system, I think that’s when writing and image making begin to rip apart. And I think those of us plagued with being makers of visual literature can’t help but see

our writing and are always trying to bring those two things back together again. So, my painting professor was right. But he was also wrong because the origins are more united. Also, I’m a bit of a synesthete, my senses are very interconnected. I think we all are born that way, hearing colors, tasting words, but our educational process forces us to separate the senses and inhabit these different cubby holes.

Brian: What about sound? You mentioned earlier that the poems in Five Oceans are essentially voice poems, but we’ve been talking mostly about the visual quality of writing and poetry. How does sound and music inform your writing process, including your collaborative work—which necessarily combines multiple voices?

Warren: Good point. We tend to think of the Gutenberg revolution as being a very positive thing. No doubt it helped to democratize the printed word, literature and literacy to more people beyond the aristocracy and the clergy. But it also helped separate storytelling from the lyric presentation of poetry. Eventually, storytellers became writers who wrote for the page more than for the campfire or the town square. I think a lot of people, including myself, have been interested in reuniting the printed page with the oral and pictorial traditions. But in visualizing the orality of speech and the spoken word, I’ve also been interested in visualizing interior narratives, and how to visualize/diagram thought, which can be different than speech.

Brian: These days, almost all information is mediated by digital devices. Do you think the internet is having similar effects on the democratization of information as Gutenberg’s letterpress did centuries ago with literacy?

Warren: Definitely. Technology always influences the means and ways of writing, telling and sharing stories, information, poetry. Digital devices and high speed internet make it easier for a more fluid mix of word and image and sound and motion and interactivity and polyvalent juxtaposition of voices. But it’s wrong to say that the internet and computers created the possibilities for thinking and working in these different modalities. We can see polyvalent literature and structures dating back to ancient illuminated manuscripts. We see all kinds of visual text compositions that were done by hand and printed on letterpress printers and typewriters, and interactive works dating back centuries. Even hypertext predates computers and the internet.

Brian: It’s hard to imagine the oral storytelling traditions of Ancient Greeks or Medieval troubadours thriving in our media ecology. What are some of the advantages and novelties, would you say, that our current technological moment brings to the literary arts?

Warren: You weren’t able to make a book that also had sound or where words literally danced across a page or protruded into third and fourth dimensions or were altered by algorithms or crowdsourcing, until CD Roms and then iPads and the personal computer and augmented software and coding enabled these kinds of things. But you were able to evoke many of these ideas previously, and you were able to have hybrid

interactions between printed objects and human beings and performance and audience before as well. Things change, but the human imagination also transcends time. There are pattern poems from the 4th century that function on multiple levels, relating to natural and supernatural planes of existence that read across, vertically, diagonally, like puzzles, in multiple colors. You have works of fiction, from the 14th century like The Decameron, which contains 100 novellas within it, and is erotic and raunchy and was illuminated with word and image, and you have Laurence Stern’s remarkably visual novel The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman, published in nine volumes in the mid 1700s that explores problems of language and misunderstanding and used punctuation and dingbats in place of expletives, and doodly lines to diagram mood and meandering trains of thought, and overprinting to signify the death of a character, and blank pages where readers were supposed to write their own responses. I can go on for quite a while before getting to the Modern

era, where we think we invented everything.

Brian: One could argue that your ideal readership wasn’t really around in the 1980s and 1990s, but that maybe has finally arrived over the past two decades or so. I mean, younger people find books like Mark Z. Danielewski’s House of Leaves easy to read. Why do you think this is?

Warren: On the one hand, I should only be thrilled about this moment we are in because I have been working on polyvalent structures and typographic/visual writing in ways that seemed very alien to people when I first started out. Now freshman college students and even high school students totally understood how to read these things and I think it’s because these books we’re talking about, mine and others, are similar to the hypertextual structures of the Internet, where you don’t have to read things in a linear way, and its visual, and photographs and maps are embedded into the text. So I am happy that we are in a more visually literate moment. On the other hand, I feel a sense of loss as well, and can lament, like Sven Birkerts does in his Gutenberg Elegies, about younger people not having the patience for long form, contemplative, interior literature. Mostly I’m optimistic and excited that young people are very engaged politically, and are intolerant of bigotry and unnecessary hierarchies, and I have students who are as serious and exploratory and brilliant as I’ve ever had. But I do have concerns about attention span. More generally, I think that the revolution that Stéphane Mallarmé and Filippo Marinetti, the Dadaists and Futurists were calling for and proselytizing, is actually starting to happen. Vis Lit was always on the fringes but now you see it popping up in bookstores and bestselling novels. It used to be 1 out of 1000. Not it’s more like 1 out of 100 books have some kind of typographic or pictorial aspects to them.

Brian: As visual literature becomes increasingly popular do you fear it will become co-opted by the mainstream and lose some of its critical grit? This is what happened to many aspects of postmodern literature, which people like David Foster Wallace warned us about in the early 1990s.

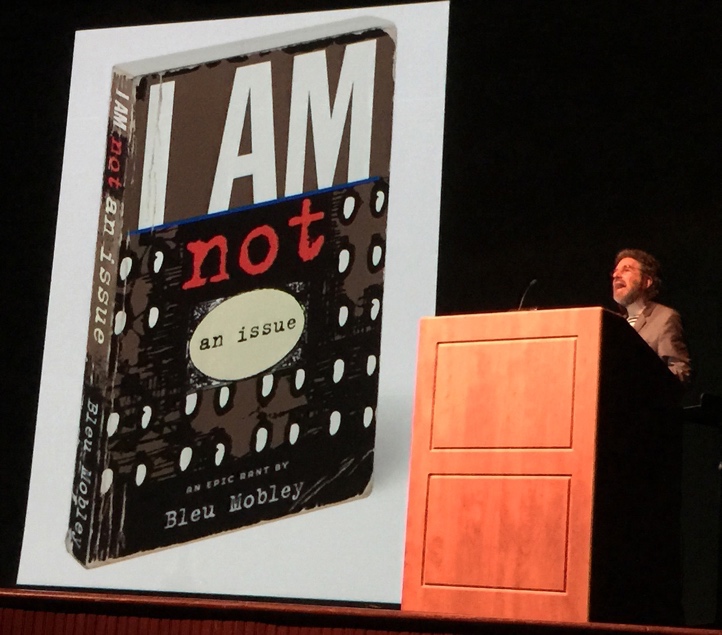

Warren: Yes, of course. In my illuminated novel A Life in Books, the protagonist/author Bleu Mobley works together with engineers from MIT to invent flying books that fly like constellations of kites over town and country. But then advertisers and politicians and other propagandists and commercial interests co-opt the technology and Bleu Mobley himself joins the protest movement calling for the banning of the technology.

Brian: You and Judith Sloan run a non-profit arts organization called EarSay, but this is also the name of the imprint to some of your early books. Would you mind talking a bit about this side of your work, the printing and publishing side of things? I’d also be curious to know more about how developments in writing software and printing have informed or influenced your creative process.

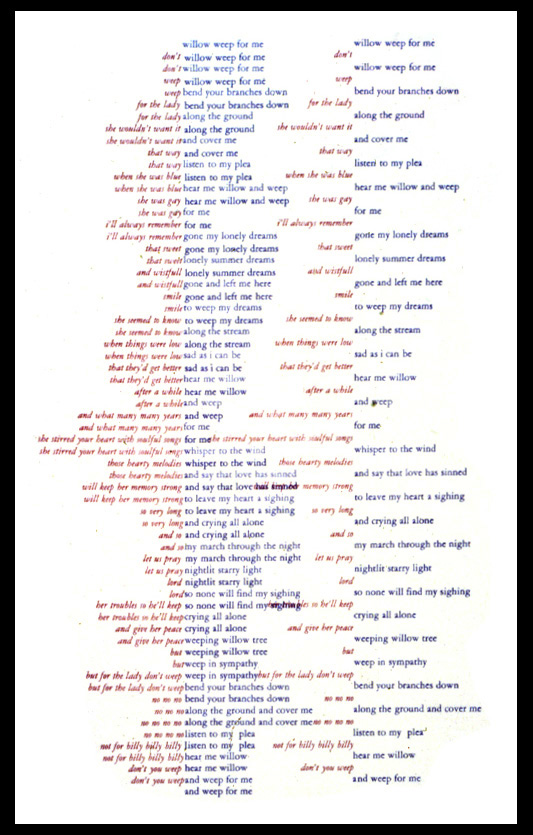

Warren: Like Bleu Mobley in A Life in Books, I was first introduced to printing via the letterpress shop in the basement of my public junior high school in Queens. But unlike Bleu, I didn’t really fall in love with the letterpress shop at the time. I was attracted to that shop more than other shops because it seemed less dangerous than the metal or wood shops. I learned how to do lithography, etching, and silkscreen as an undergraduate at CUNY. When I went to graduate school at Yale there was a letterpress shop that no one was using where I retaught myself how to set type and began making these letterpress mash-up performance scores.

and “Don’t Weep for the Lady,” 1979

One of the reasons I went to graduate school for graphic design instead of creative writing was to learn the tools and methodologies of printing. At that time, the technology for typesetting, besides letterpress, was phototypesetting. So you have a computer front end where you program typeface changes and point sizes, and it would come out on rolls of photographic paper and then I would cut and paste that stuff. So mechanical paste-ups became another part of the process. If I wanted the type to curve, or the baseline to shift, I couldn’t do that with the computer. I had to cut it up with an X-Acto knife. If I wanted type to go on an arc I had to cut between every letter of a word and manually manipulate and use wax to glue it on bristol board. A lot of labor intensive handwork.

Both i mean you know and French Fries have EarSay listed as the co-publisher, but the other publisher was VSW, Visual Studies Workshop, which is an artist access publisher and school with offset presses and other kinds of presses and bindery. I received project grants from the New York State Council on the Arts, and I would go up to Rochester where VSW still is and work with the printer and Joan Lyons the Director of the press at that time who had a vision about artists’ books and artists and writers having a hand in the production process. In 1988, when GRRRHHHH came out, which I printed at The Center for Editions at SUNY Purchase where I teach, I still wasn’t the printer operating the offset press, but I worked with former students who became printers and they ran the press, and I worked and reworked the book while it was being printed, learning from happy accidents that happen during the setup of make-readies used to get the ink just right before you say, “Okay, now we’re going to let it roll.” I printed that book in dozens of colors including metallic colors and employed overprinting and used some of the same plates on different pages. So there’s a relationship to printing that isn’t just mechanical, like here print this.

Nowadays, my relationship with the printer is less fluid. But I still like to sit on press

to make sure the quality of the printing is good, and the colors are close to what I envisioned. I also like to make sure that the paper is archival and off white and soft to the touch and the binding is smythe sewn. None of my books have ever been perfect bound,

which is an oxymoron because perfect binding

is just about the most imperfect kind of binding you could possibly have. Now that I’m no longer the publisher of my books, I’ve lost some of the control, you know, it’s a trade-off. I am happy with the production value of Five Oceans in a Teaspoon and A Life in Books which were both well produced.

I came up with EarSay as an imprint in 1983 and then when Judith and I got together in 1990 we soon created a non-profit arts organization and named it EarSay. The idea is: We listen with our Ears, hear stories, ears to the ground, look for soul and character and evidence of the communities and world we live in. And then it goes through our ears into our creative processes and our bodies and craft and produce projects that manifest as theatre, as books, as animation, audio works, radio. That’s the Say part. We also run educational programs with immigrant and incarcerated youth, helping them learn the tools to tell their own stories.

Brian: Do you think all art is collaborative then?

Warren: In part. Even art that is made in isolation has a connection to antecedents and to a culture if not a variety of cultures. There are artists who are very autobiographical, who look inward and are always writing about their own experiences. And then there are artists who look out more at the world and to other people and try to translate their findings. Journalists and documentarians do that more. I’m a little more of the artist who looks out. Even Bleu Mobley, the protagonist and narrator in A Life in Books, was mostly inspired by other people and the stories and issues of interest to him that are churning in the world, until finally he found himself in prison and had his own story to tell, and he succumbs to writing an autobiography, of sorts. And in so doing he comes to realize that he was always writing about himself and the people around him.

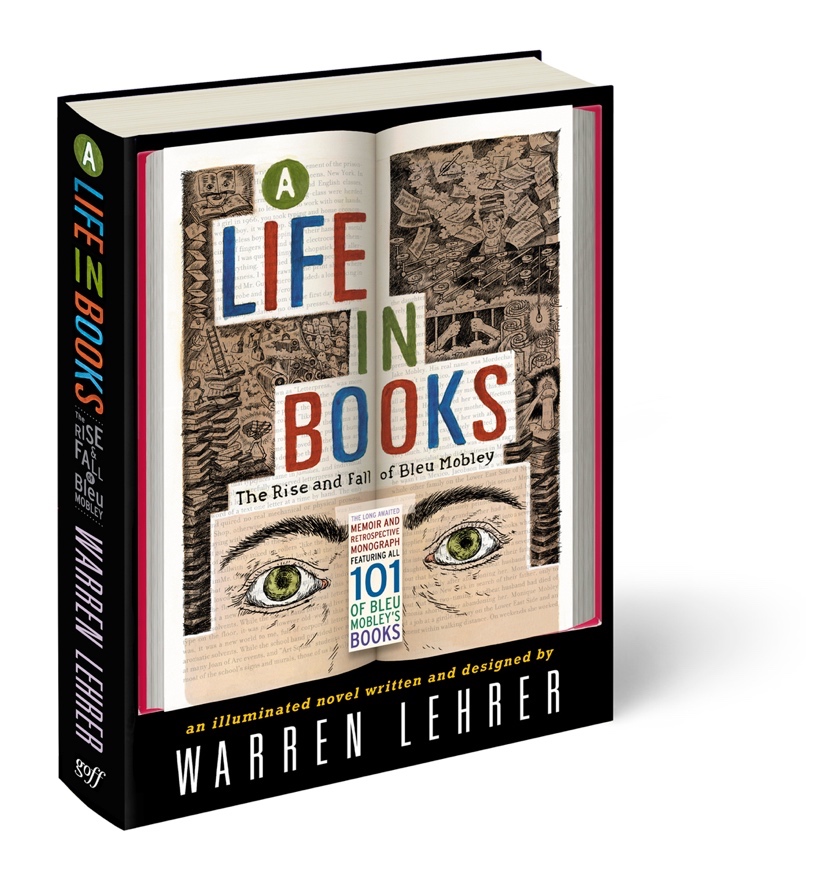

Brian: You have referenced A Life in Books a few times now, and as you know, I first came to your work through A Life in Books: The Rise and Fall of Bleu Mobley, so let’s focus on it now. A Life in Books is a novel presented as a retrospective monograph of a prolific fictional author named Bleu Mobley. Among other things, the novel provides a tour of the publishing industry—mediated by Bleu’s autobiography and excerpts from 33 of his 101 published books—beginning in the 1970s and that becomes increasingly bleak as the narrative moves closer to the present. A Life in Books is a literary compendium, a love song to the book as object, but it’s also a parody of the demise of publishing and of an informed and curious readership. Where did the ideas come from for this project, which is quite expansive in its engagement with literary and print culture?

Warren: A Life in Books was spawned in reaction to my previous five books, which were documentary, nonfiction works. Crossing the BLVD documents 79 real people from all over the world who live (or lived) in Queens, and before that The Portrait Series consisted of four books, around 250 pages each, that document real people, eccentrics, their life stories and perspectives through narrative and pictorial portraits. There is a lot of responsibility when you’re representing real people. It requires a certain way of working—listening to peoples’ stories, finding the arc of a life and giving visual form to them as well, which I loved doing, but I felt a real need after those five books to work on something that gave me more room for invention. Also those oral history-based projects are confined to the things people tell you, which can get very deep and intimate, but can also only go so far. I had a hankering to create an interior narrative, actually multiple interior narratives. It began with a notion about a character who is a prolific writer looking back on his life and career from prison, a place where a person needs to go inward to survive, particularly if you’re a writer; a place where you need to take stock of your life—a kind of how-did-I-end-up-here narrative. I also had all these book ideas in my head and in notebooks. Not all of them ended up in the novel, maybe a dozen or so did, and I had a bunch of short stories that I had written which had potential connections between them. Those were starting points. In the end, more than anything A Life in Books became a book about the creative process and the relationship between an artist, in this case a writer, and their work. I generally have found films about artists to be extremely unsatisfying. Usually there is a lot of emphasis on drug and alcohol addiction and dysfunctional relationships and a lot of hanging out at bars and having sex, and then somehow the person manages to make paintings or gets up on stage and plays amazing music, and there is hardly anything about the craft involved and the complex relationship between life and art. I was interested in exploring the inner workings of an artists’ craft and the oblique relationship between the life of the artist and their art, how the characters a writer writes reflect the self, the people around her or him and the greater world they’re a part of, and how the story you tell yourself about who you are can also be different than the narratives in your creative work, and different than how others perceive you. I was interested in juxtaposing those things. How life writes a person, as well as how a person’s work writes their life. The whole process of writing A Life in Books was very mysterious involving a back and forth between writing Bleu’s story and writing the book excerpts and designing the covers. The book titles and covers are often funny or satirical, but the content/the excerpts deal with characters grappling with serious stuff, life and death issues, war, disease, discrimination, difficult relationships.

Brian: There is certainly a lot of humor running through the entire book. I’d say the treatment of the material is usually comical, but the material itself is quite serious, often very political too, which makes for good satire.

Warren: What I think I tried to do is not satirize characters, but institutions. I punch up at institutions—the publishing industry, the medical and mental health systems or the lack of them, U.S. foreign policy—but treat the characters with compassion and as complex beings even if they’re not necessarily heroic. Then within their stories I portray the humor the characters find even through hard times. That’s the way I experience life, tragedy and comedy bundled up together.

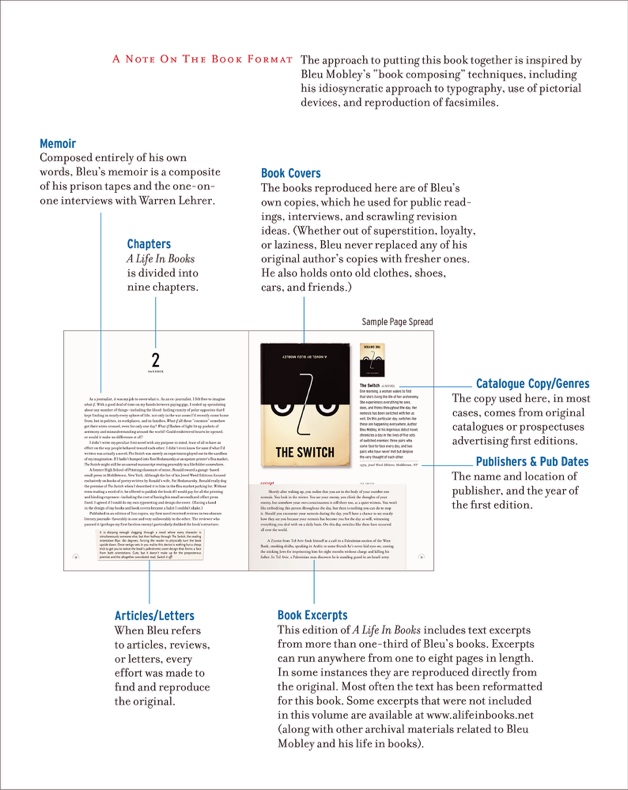

Brian: At the beginning of the book you provide a diagram that explains its format. Readers learn that the book consists of mostly memoir, but throughout the book there are images of book covers, reproduced news articles and letters, catalogue descriptions, publisher and publication dates for each book’s first edition, and of course book excerpts, which range anywhere from one to eight pages in length. Virtually every textual object functions, I would argue, as a PART FOR THE WHOLE metonymy. The reproduced photographs of Bleu’s books stand in for the physical book object as a whole; they are partial representations that index and provide mental access to each book as an object. The book covers stand in for some aspect of each book’s content as well, inviting metonymical and/or metaphorical interpretations. Furthermore, each of Bleu’s books is reflective of a technological stage in the development of printing. As for the snippets, these are meant to function as metonymies of entire reviews as well as of the attitude of readers towards Bleu’s books. The catalogue descriptions summarize each book, and although the 33 excerpts from Bleu’s books are not taken from actual books, readers are asked to interpret them as metonymies for each one as well as for pivotal moments in Bleu’s life. Given that many of the events narrated in Bleu’s memoir index actual historical events, both Bleu’s life and his books stand in for or index historical events in the real world too. Even the title of the novel is metonymical: Bleu doesn’t merely spend his life making books, his books stand in for his life (his life in books). Were you actively thinking in these terms while writing the book?

Warren: Yes, I was thinking of all of those things, except for the words metonymy and metonymical which I never heard of until I came across your use of them in relation to A Life in Books and other works. One of the reasons I call it an “Illuminated Novel” is because I didn’t want the book covers and excerpts and catalog descriptions and reviews to illustrate the memoir part of the book. That would be redundant. I wanted each aspect to illuminate each other, the life and the work, the images and the text, and to carry the whole thing forward. And hopefully readers noticed that certain things going on in Bleu’s life don’t show up in his work until 20 years later, and maybe the gender is different than the person who inspired the character, and aspects of Bleu's personality might show up as aspects of certain characters but in other respects those characters might be very different from him, and situations show up in his books that he didn’t experience directly but reflect things going on his neighborhood or the United States or the world.

Brian: What are the various effects, do you think, that result from employing your well-established documentary aesthetic within a work of fiction? Do you think these metonymical devices help the novel achieve a heightened level of mimesis or verisimilitude?

Warren: I’m generally not that interested in works of fantasy as I find the world we actually live in to be quite strange and fantastical already. So that is my starting point. Magic realism interests me because it’s usually rooted in a naturalism and then some seemingly unnatural things happen like dead people still keep showing up and dream and waking states flow into each other. I’m a student of dialogue, foremost; I sit in awe at the waterfalls of spoken word, the way people talk and what they have to say. I’m also a student of culture (high, low, sub, pop, avant-garde) and the artifacts people produce and consume: books, newspapers, magazines, films, media, advertising, personal letters, public letters, typography, photography, graffiti, the clothes people wear. Many of those artifacts have a lot to do with texts but their visual aspects also embody/deliver information, connotation, context, time, place, authenticity, shared tropes as well idiosyncracies. So when I’m designing the book cover of a culinary murder mystery by Bleu Mobley (say, The Night Crustaceans Screamed

), I’m not only playing off the milieu of murder mystery book cover designs and cookbooks of that particular time period, I’m also developing Bleu’s personal graphic style since he designed his own covers and for the most part was self-taught and worked in opposition to genre. The covers reproduced

in A Life in Books are said to be of Bleu’s original first edition copies, so they show different degrees of wear and tear. My approach to the writing and the visuals is similar. Writing a newspaper article that Bleu wrote in the 1970s covering a CIA-funded slaughter in Haiti is different than his experimental novel writing (like his 365 page one sentence novel that takes place over the course of a few hours inside the mind of a man painting a red house red), which is different than the writing style of a children’s book (like Bleu’s pull-out, pop-up book on the history of capital punishment titled How Bad People Go Bye Bye

). And Bleu’s running narrative (as whispered into a microcassette recorder over the course of one sleepless night in his prison cell) needs to read and look different than his cultural productions and the reactions to them. I guess you could call it an extended kind of world building

or universe building that I think/hope adds to the reader’s experience of the novel.

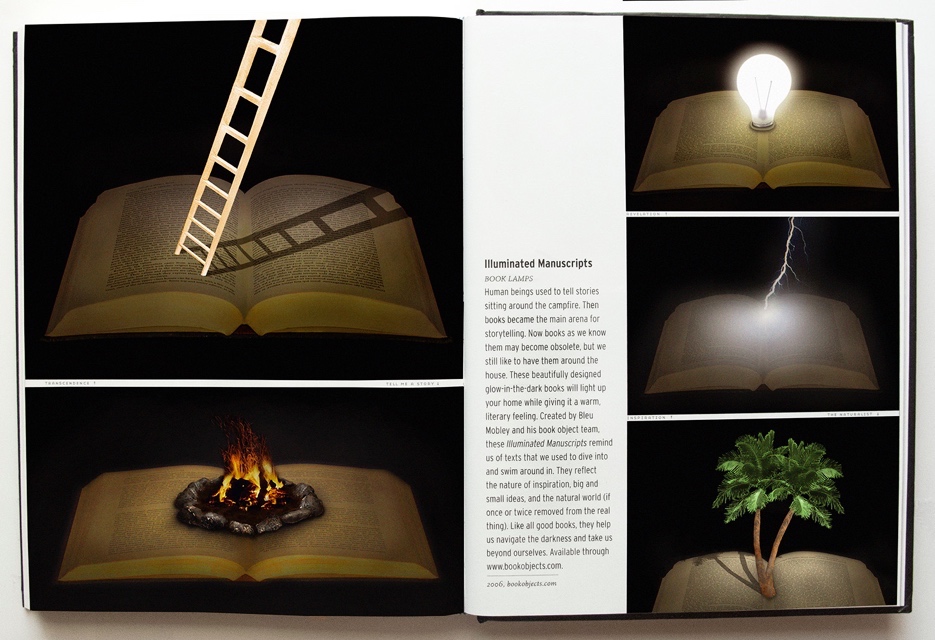

Brian: Bleu makes all kinds of books, some of which you just mentioned: scrolls, letterpress books, dos-à-dos books, repurposed artist’s books, works of bibliocircuitry, virtual reality book-installations, and of course he cuts across virtually every conventional genre at some point. In other words, this is not merely a novel about Bleu’s creative process as a writer and bookmaker, it’s about the institution of literature and publishing, and how they’ve changed over the past few decades. What is this book trying to say about the history and possible futures of literature and the publishing industry?

Warren: There are several branches of thematic interest running through this book, and certainly changes in the publishing industry and the future of literature became prominent ones. The parallels to Bleu’s story go further back than just a few decades. Bleu’s first encounter with printing and making books begins with letterpress which brings us back to Gutenberg and the invention of moveable type, and then his evolution parallels the evolution of centuries of technological changes in printing and in publishing. And before there were books, there were scrolls. Bleu makes those too. My process of bookmaking paralleled some of these historical developments as well, even though I was barely conscious of those connections at the time. It was similar for Bleu. We see him go through all of these different technologies and come to writing and making books very innocently, very idealistically, out of a need to make some sense of this crazy life. He isn’t thinking about genre or money or the literary market, his writing and his books come out of him organically. It isn’t until his daughter gets sick and he needs money to pay for her medical care that he is motivated to commercialize his writing. Even then he is still trying to be true to himself, trying to understand what genres are and work within them. At one point he goes to a big box bookstore and lies down in particular aisles until an idea for a book in that genre comes to him. It’s funny looking at it now, the big box bookstore was the boogieman when I wrote the book, but now when you find out a Barnes & Noble is closing, it’s like oh my god, that's terrible. Bleu struggles to meet the needs of his publishers and to provide for his daughter and mother and his own increasing material needs, and eventually he comes to realize that people are not reading like they used to, so he works on figuring out alternative ways to deliver literature and stories to people and to preserve books at least as objects. So yes, I’m playing with all of that stuff.

Brian: Late in Bleu’s career he begins to make some pretty wild and impractical books, like a book of poetry on toilet paper, a mini television built into a book, flying posters with poems written on them, and various types of bookish furniture and children’s toys that look like books. It seems to me that you are satirizing readers-as-consumers, here. I wonder how in addition to providing a tour of the publishing industry and of the history of the book, you are also satirizing changes in contemporary readership. I mean, Bleu begins as an experimental novelist and ends up mass-producing a line of self-help books with a staff of writers.

Warren: Increasingly as more and more people spend more and more time staring into and fingering their cell phones, readers have less and less attention span and time to read. And as much as Bleu loves the book as a medium, with his Allbook, a multi-sensorial electronic reader, for example, he goes completely digital—with a platform that includes a glove that enables you to feel what the characters are feeling, and nose plugs to smell their smells, and head sensors to see what they are seeing, so nothing at all is left to the imagination. That is a send up of the technology to an absurd degree, where every book is a film, where there is nothing left to the imagination, where every literary idea needs to be expressed through a kind of sensory overload. But I try not to spoof the reader or any of these characters. I still come to them with empathy, while I feel free to spoof the culture and the institutions.

Brian: Bleu tends to write books in order to fulfill some kind of wish or fantasy. One could argue that he creates books in order to symbolically resolve problems or tensions he experiences in the real world. Do you think this is one of the main purposes of art?

Warren: The book Bleu composes at fourteen years old about his mother, The Grandest Art Show in the World, sets him up for writing nonfiction, whereas his My Famous Father series, also composed when he was fourteen, fulfills the need to invent a world that doesn’t exist, since he didn’t have a father and his mother never told him who he was. Those first two book projects set the stage for Bleu’s creative output for the rest of his life. 1. Trying to make sense of the world around him through reportage, and 2. Trying to fill the holes in his life by dreaming up stories. Very early on he has a conversation with Mr. Guy Gutiero, his shop teacher who is a newspaper guy, about the difference between fiction and nonfiction. Bleu doesn’t understand why nonfiction has a non- prefix when it’s the truth. Ultimately Bleu gets into trouble when he blurs fiction and nonfiction. In the end, he vows to himself that he is not going to write any more books so he can live more fully and not always have to turn everything into a book, as Mallarmé famously put it. The reader shouldn’t necessarily believe that Bleu is capable of wrenching the writing of books from his life, but he messed up royally and wants to be a better father, husband, human being.

Brian: Toward the end of the book, we eventually find out why Bleu is in jail. Bleu writes a work of fiction called Under the Rug about the scandalous behavior of GW Bush, but it’s marketed as a work of nonfiction, an insider’s narrative meant to bring down his administration for its lawless behavior and war crimes. But even though the book is not an authentic record of history, the Bush administration interprets it as fact. Bleu is called before a grand jury and questioned by a federal prosecutor who demands the name of his source. Refusing to comply, the judge sanctions Bleu to a federal detention center claiming his silence showed contempt of court. We know why Bleu doesn’t confess—he’s the source. But the point I’m trying to make is that the administration treats a work of fiction, within the court of law, as a factual narrative. I’m wondering what you might be suggesting here about the consequences (societal, moral, political, historical) of not distinguishing the boundaries that separate factual narratives from fictions and how we might reexamine this element of your novel through the lens of what is sometimes referred to as “post-truth” (e.g., Browse 2017; Worthington 2017), the notion that objective facts are less influential in shaping public opinion than appeals to emotion and personal belief.

Warren: Bleu has had this confusion since he was a kid between fiction and nonfiction, and blurring the lines, or trying to understand the distinctions. By the end, he’s also having some kind of a mental breakdown bordering on psychosis, so during that time he very well might have lost track of what’s real and what’s not. At the same time, macro, you had an administration in Washington—of course, now we equate Trump and his administration as the number one perpetrators of lies and of constantly accusing everyone else of lying—but the GW Bush regime lied a heck of a lot too. The Iraq War was premised entirely on a lie and resulted in perhaps as many as a million people getting killed. So, the lies aren’t just a stylistic thing, they’re not funny anymore when they start a war and set off a horrible chain of events in a whole region of the world and beyond. That's why Bleu was willing to do a hit piece on the president using the most salacious and titillating means possible, to try to bring him down. If you love reading and writing novels, then fiction is a unique means to getting at deeper truths. But when you’re talking about politicians with a lot of power making up stories about weapons of mass destruction that don’t really exist, then fiction

becomes a crime against humanity. So the question of what is truth, what is myth, what is fiction, is no longer academic when a lie is elevated to very real life and death, war and peace consequences. As for the White House in A Life in Books, there was probably a kernel of truth to what is described in Bleu’s book, of an illicit affair and some other untoward behavior that motivated a former White House cleaning person to approach Bleu with the basis for a flush and tell

book. I don’t go into the exact details, in either the excerpt or in Bleu’s retelling of the events. But this gets to one of the novel’s big secrets. He’s not protecting his source; he’s protecting the fact that he made most of it up and he’ll be found out to be a fraud if he tells the truth. I like the fact that he’s in prison for an intellectual crime. There was no stabbing or robbery, just a pathetic intellectual crime confusing fiction with nonfiction.

Brian: But what about his justification? It doesn’t seem like simply a matter of confusion; it seems quite deliberate. Bleu believes his actions are morally justified. As he puts it: “I knew that I had played fast and loose with truth. But in my heart of hearts I believed that a greater truth was being served. I believed I was morally justified fictionizing a story that could take down the most powerful man in the world—a man who lied to bring his country to war, lied about torture, lied about spying on his own people, lied about the science of global warming and the fate of the planet, lied about so many things that imperiled millions of lives” (363). Under the Rug is meant to function as a noble lie, a lie that serves the public good regardless of its inveracity because it serves the greater good of society.

Warren: As you read that quote, it reminds me of Alan Dershowitz’s defense of Trump, saying that well, if he truly thinks that his reelection would be for the betterment of the country, then there’s no crime involved because he's acting on behalf of the country. I can’t justify what Bleu does, but of course people lie all the time, they think for good reason, to protect people they care about, fill in the blank. Bleu got himself into a pickle. I do think, especially now, the separation between what is true and what is not true is even more important a question than when I wrote A Life in Books, and it would be pretty easy to replace Bush with Trump, in fact I never mention Bush by name. You know Kurosawa’s film Rashomon? When I came of age, it was such a revelation to see a portrayal of the same story through different perspectives. Same thing with Russel Banks’ incredible novel The Sweet Hereafter, about a school bus accident where all these kids die, but there are survivors too including the bus driver, and the novel is written from all these different points of view telling different sides of the story. There was a film based on the novel that is also very good. And Rashomon was based on a short story. But the idea with all these multiple narrator works is that you’re getting all these different points of view. That’s part of what cubism was about, seeing the same thing from different angles. That’s what Einstein’s theory of relativity helped create in the modernist era—an understanding that there is no one reality. The truth depends on where you are. You’re playing ping pong on a moving train. Are you standing in one place or are you moving? Relativity paved a way for the exploration of artistic relativism. And you know, that concept used to be such an eye opener and invitation for me, artistically, but now it’s like, No, wait a minute. This has gotten out of hand. The fact that Democrats and Republicans in the U.S. see such different realities now on so many matters that should otherwise be objectifiable facts, and a president can invent lie after lie after lie and 40% of the population believe him because the truth and science don’t matter anymore. That’s just plain scary, not eye opening or cool or interesting. Ultimately, I’m critical of Bleu making a rationalization to blur fiction and non-fiction for what he perceives to be a greater good.

Brian: What used to be a mostly literary trope, the perspectivism of modernism, ontological metalepsis in postmodernism, and blurring the boundaries between fact and fiction, document and hoax, has now entered mainstream public discourse, so that, as you say, people in this country seem to be living in very different realities. But what used to be relegated mostly to the domain of art and literature has not merely seeped into public life, it’s destabilizing our institutions and undermining our democracy, not to mention the climate and stability around the world. I would argue that our society is experiencing a serious crisis in interpretation. What do you think we should attribute as some of the leading causes for these societal changes? Life is imitating art a bit too much, don’t you think?

Warren: It’s a perversion of something good and truth seeking. If I’m sitting on a moving train, it’s true that I'm both stationary and moving at the same time. It's also true that with all the different people in a single train car, there are many different realities, stories and points of view in the car. But when a politician takes advantage of that relativism to say that the train doesn’t exist, or only the white people on the train have value, or the earth is flat, or he scares people by making up a story that a train from Mexico is heading towards our train and we’re heading for a crash, that’s a perversion. Hitler and Goebbels were devilishly shrewd using and manipulating the Big Lie. Somehow that didn’t destroy our ability to separate that kind of horrific fiction-making from so many great works of fiction written in the 1930s and 40s. I think we’ll be able to get through this, but for sure, the Creature in the White House and his people are fucking everything up for now.

Brian: You also created a travelling exhibit of Bleu Mobley’s life work which you have displayed in several gallery spaces across the country. In this context, the 101 book covers, as well as all of the novel’s supplementary materials, are intended to be looked at and admired as authentic reproductions of Bleu’s oeuvre. When you remediate these objects into the space of the gallery, they lose their narrative framing and become decontextualized from their function in the novel’s narrative progression. What do you think the space of the gallery offers readers of this novel that they cannot get by reading the book? I mean the spatio-temporal experience of reading a novel is very different than that of walking through a gallery or a museum.

Warren: It’s different because you can’t expect a viewer in an art gallery setting to spend the kind of time you spend reading a 400 page novel. But they are prepared to take in the more visual aspects at a larger scale. And I still provide narrative context and I indicate in the opening didactic panel that the work and Bleu Mobley are a fiction, even though we call the exhibit A Retrospective.

When I give my live presentations, starting with the launch event (and I’ve done nearly a hundred A Life in Books presentations since), in the Q&A afterwards there is almost always the question, “Where is Bleu Mobley now? Is he still in prison?" When I say no he’s made up, he’s a fiction, it’s all a fiction, there’s often a collective gasp, a chorus of “What!?” A lot of people think I’m discussing the life and works of a real author. Even some people who have read the book have contacted me wondering why they can’t find his books anywhere.

Brian: When you give these presentations, you present yourself as a character named “Warren Lehrer,” your fictional doppelgänger of sorts, who assembles and edits A Life in Books. As such, this novel integrates autobiography with fiction, what critics sometimes refer to as “autofiction” (e.g., Worthington 2017; Krogh Hansen 2017). During these exhibits, the book’s textual artifacts are presented as being authentic objects created by Bleu Mobley himself, not you the actual author of these things. I guess I’m curious to know why you continued to blur the boundaries between fact and fiction in your presentations and gallery exhibits and exhibits in light of the negative consequences such actions result in in your novel.

Warren: As I said, there’s a large panel in the exhibit that says it’s all based on a novel, and on the cover and title page of the book it says it’s a novel, and on the copyright page it says it's a work of fiction and all incidents and dialogue, and all names and characters with the exception of a few well-known historical and public figures, are products of the author’s imagination—that whole disclaimer. All of which doesn’t seem to stop a percentage of people thinking it’s all real. But the book came out in 2013, so now, as we're talking about this in this post-truth age, it may be even more relevant and serious an issue, but maybe not as funny. I have to admit, at first, I felt bad that some people felt fooled by my presentation, because I wasn’t trying to fool anyone. Ever since that first live presentation, I’ve made sure that whoever introduces me says that it’s a work of fiction, mentions the two awards for fiction A Life in Books received. But I don’t press the point in my presentation, because there’s a part of me that enjoys the sleight of hand. And it’s kind of a complement, that readers and audience members suspend their disbelief to the point that they think Bleu Mobley’s life and books are real. And of course there’s a verisimilitude to the visual documentation

of the books and articles, letters, all of that. That’s part of the artistry.

Brian: Now that Five Oceans is out, and has been very well received by critics, what’s next—are you writing another novel?

Warren: I’m currently working on TRACE: A Surveilled Novel, which made its first appearance as one of Bleu Mobley’s 101 books in A Life in Books. The premise being that everything in TRACE is known by virtue of currently available surveillance technologies from email and social media intercepts to surveillance cameras, medical, FBI, IRS, police, personnel, medical files, to GPS and RFID trackings and all things slurpable on the internet. Now that it’s becoming its own full length novel and not just an excerpt, TRACE has taken on a life and structure I hadn’t thought of originally. Turns out, the whole book is presented as a document dump released by someone who works for a CIA contractor. The book begins with her being interrogated for misusing her arsenal of surveillance tools after she accidentally discovers something about her own family. It’s a lot of fun but also very challenging to write because everything a reader gets to know about the characters has to be known either because the subject

said it or wrote it themselves or by observing them and their actions. That makes it hard for me to get into the interior narrative I love so much about novels. So writing TRACE also puts to the test the notion that most of us are overexposed by these technologies, not just our addresses and phone numbers or our buying habits and political proclivities but also our inner lives, deepest feelings, thoughts and longings.

I’m also working on the first digital/app edition of the literary/art magazine Carrier Pigeon which is published by Paper Crown Press the same folks who published Five Oceans in a Teaspoon. My piece in there is a story I’ve adapted from A Life in Books called Riveted in the Word, about a woman recovering from a stroke. This iteration of the story plays up the visual experience of a narrator having a lot of cognition and memory while struggling to regain her grasp of language. In designing it for an interactive platform I’m trying to split the difference between reading a book and watching an animation. In one the reader has control over the pacing and the text lives mostly within a column, and in the other, the words and typography are more performative. Words are appearing, disappearing, coming in and out of focus, changing scale, trying to find memory of themselves. So the experience of reading/watching the piece is almost like being inside someone’s mind who is trying to regain language after a stroke.

Brian: What software are you using to create this piece?

Warren: I’m working with a programmer, Artemio Morales who is coding it all. I design and storyboard it and Artemio programs it. And then we get together and tweak. In the end it’ll be seen on an iPad or Kindle Fire or a good-sized smart phone. I’m also consulting on the design of the other pieces in the digital issue as well as designing the next print edition of Carrier Pigeon and contributing a story for that as well.

Brian: Thanks for chatting with me Warren. I’m very excited to read TRACE when it comes out, which sounds like a very compelling novel and multimodal book-archive about the state’s growing surveillance apparatus in the current media ecology. And I’ll be sure to check out the first digital edition of Carrier Pigeon, which sounds like a very promising and unique home for future experiments in multimedia literature.

Warren: Thank you, Brian. I really appreciate your very close reading and analysis of these works. It’s been a pleasure.

References

Bernstein, Dennis J and Warren Lehrer. Five Oceans in a Teaspoon. Paper Crown Press, 2019.

Birkerts, Sven. The Gutenberg Elegies: The Fate of Reading in an Electronic Age. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2006.

Browse, Sam. “Between Truth, Sincerity and Satire: Post-Truth Politics and the Rhetoric of Authenticity.” Metamodernism: Historicity, Affect and Depth After Postmodernism, edited by Van Den Ackker, Gibbons, and Vermeulen, Rowman & Littlefield, 2017, 167-181.

Hansen, Louise. “Is Concrete Poetry Literature?” Midwest Studies in Philosophy, 33, 2009, 78-106.

Krogh Hansen, Per. “Autofiction and Authorial Unreliable Narration.” Emerging Vectors of Narratology, edited by Per Krogh Hansen, John Pier, Philippe Roussin, and Wolf Schmid, De Gruyter, 2017.

Lehrer, Warren. A Life in Books. Goff Books, 2013.

___. i mean you know. Visual Studies Workshop Press and EarSay Books, 1983.

Lehrer, Warren and Dennis J Bernstein. French Fries: a play. Visual Studies Workshop Press and EarSay Books, 1984.

Lehrer, Warren, Sandra Brownlee and Dennis J Bernstein. GRRRHHHH: a study of social patterns. EarSay, 1988.

Rigolot, Francois. “Le Poetique et l’analogique.” Poetique, 35, 1978, 267-68.

Worthington, Marjorie. “Fiction in the ‘Post-Truth’ Era: The Ironic Effects of Autofiction.” Critique, 58.5, 2017, 471-483.