"A Snap of the Universe": Digital Storytelling, in Conversation with Caitlin Fisher

In this conversation with ebr Editor Lai-Tze Fan, internationally acclaimed artist Caitlin Fisher talks through her origins, inspirations, and processes with a clear message: things can always be unlocked with more than one key and stories can always be told with more than one method. Fan asks Fisher about the 20th anniversary of These Waves of Girls at the end of Flash, the archival impulse of her stories from doll collections to hand-held museums, and the importance of creating tiny stories out of high technologies and giant institutional labs. Of the many lives Fisher has already lived and of her works to come, this conversation gives only a glimpse—a snap of the universe.

Lai-Tze Fan: Hello, Caitlin. My first question for you is short and simple: how did you get into electronic literature? How were you introduced to the field?

Caitlin Fisher: My doctoral work is in Social and Political Thought, and I’d done a double major in Economics and Women’s Studies. I was TAing in Women’s Studies and one of the things that I recognized—this was in the nineties—was that all of the syllabi and the arguments that were particularly heated at that time in feminist circles were around the origin of analysis. Do you start with the suffragettes? Where do you begin? With CD-ROMs I realized you could begin anywhere. You could begin globally anywhere. You could begin temporarily anywhere. You could begin in the Middle Ages. You could begin with a vote. You could begin with the forties. You could begin with the 17th century.

It was like a light bulb went off where I realized that being able to access knowledge in a way that moved beyond the printed page allowed more than changing the content or offering an alternate syllabus. It really concretized an epistemological shift. What digital tools could do was have a whole universe of ideas open up, simultaneously, and I was way more interested in that universe of ideas than the page.

There’s a quote by Deena Larsen about setting up strings and trains as part of her writing process. This was entirely resonant with my graduate work. For my Master’s thesis I had ended up in an empty room with about 300 pages over all of the walls—and the ceiling—and the floor—and connected with string. My struggle had always been: how do you get all of this, all of these associative mappings, onto a page? It wasn’t actually the content, it wasn’t actually the researching, it wasn’t actually the putting things into relationship. The struggle was focusing into that form. When I realized that you might not have to focus into that form, that there could be ways that you could communicate these associative mappings—and these to my mind, much richer relationships—that was just really revelatory and it kind of went from there.

Images from Fisher’s dissertation in development. Source: Caitlin Fisher.

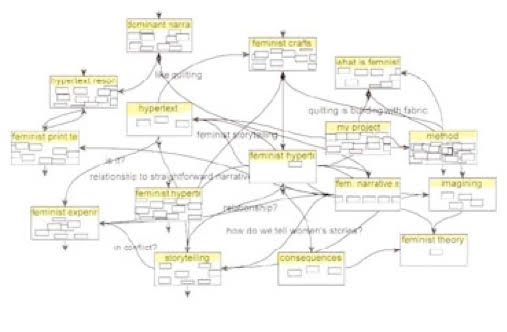

My doctoral work was not fiction. In spite of people thinking that I did a work of fiction for my PhD, I did not. [My dissertation] was very theoretical and it was called Building Feminist Theory: Hypertextual Heuristics; I started to look at feminist hypertexts and digital technologies—not specifically electronic literature, but the digital capacity to think differently, and this included electronic literature.

I was working in Storyspace and the method itself was so intriguing, basically producing a knowledge domain visualization. I realized that one of the guiding principles that I was looking at for building feminist theories were these multimodal works that could be multivocal, that probably could include fiction and poetry alongside theoretical texts. I was looking to story quilts and early feminist zines, thinking of the way in which theory was always advanced by using art and literature and poetry. When I really got into the groove of that, I [wondered]: what would experimental poets of the [nineteen] twenties be doing? They’d be working in hypertext, they’d be working in these areas. Then there was kind of no turning back. I thought electronic literature is actually sort of the end game for where all of that was going. It was super fun! I’ve written about it elsewhere, but the dissertation itself I was enormously proud of. Writing it changed me.

Image from Fisher’s dissertation. Source: Caitlin Fisher.

There were really no readers for it at the time I produced it. It wasn’t even archived. The electronic literature piece that I turned around and produced immediately following that, [These Waves of Girls (2001), let me take] all of the lessons learned in my dissertation and leverage those lessons by doing the exact opposite. Waves was very character driven, I tried to make it much more crowd pleasing and much less clever. I tried to write something people would want to read. It was actually an amazing lesson to think that, especially with digital literacies and emerging literacies, that there are always important tensions between pushing people experimentally and allowing people to find pleasure where they are. That’s been a guiding principle in much of my work.

When do you actually think about advancing avant-garde forms as the main goal and when do you think of communicating the stories as the main goal? And when can you do both? And how do you do both? So that’s sort of how it happened. I realized that after many years of working in the academy, that for many of us who write fiction or poetry, there had always been writing. I’d always been part of writing groups, all through my doctoral work, but I’d always thought of my creative writing as being tangential to the main work of academic research. Electronic literature was actually an incredibly important homecoming in terms of being able to say: these things don’t have to be in opposition.

L.F.: The description of your origin story into e-lit resonates with me in that a lot of personal evolution has got to come through finding things coming together that happen to make sense: this led me here, that led me to this point.

You spoke of your disciplinary positionality at the very beginning. You mentioned that your PhD is in Social and Political Thought, that you have a background in Political Economy and Women’s Studies, and you’re also a creative writer and feminist theorist, an artist, a professor—many other things. I want to ask about that disciplinary positioning for e-literature, because I think that e-lit practitioners and scholars can be found in various disciplines and departments. How much does one’s department or discipline really matter in regard to how we engage with e-lit in our education, training, creation, pedagogy, or the parameters or expectations of research? Is it important to be interdisciplinary—and if not in training then maybe in imagination? C.F.: I think it’s changing now, but I think my career is slightly different than other people’s because many people in that first generation of e-lit scholars—in those early days of the establishment of electronic literature and the establishment of the ELO—most of the people who were doing e-lit were typically professors of English and typically people who would imagine themselves as writers. In some ways, there are more people now who probably have careers that are nearer my own, just as there are novelists who are firefighters and doctors and security guards and waitresses. If you write, you can really come from anywhere, but it’s also not true that it doesn’t make a difference where you start. My e-lit can’t help but be influenced by training in an expansive, theoretical and political way of approaching the world.

And to come from a place where I had to struggle around doing creative work, making it fit, and to then be immediately hired after my PhD into a Faculty of Fine Arts, largely on the strength of an e-lit and digital practice, to be hired into a place where the real work is the creative work, to be surrounded by colleagues and students whose formation was: in order to understand things, you make things—where there was no apology around making as a route to knowing things—was amazing to me. Landing in Cinema and Media Arts probably made my work more visual than it might otherwise have been. And I may never considered AR as a literary medium if my institutional location had been different.

In some ways it was a more circuitous journey, but also a super interesting one, and very different than if I’d said, “I’m going to be a creative writer.” In retrospect I see that I tried really hard to get into e-lit—or at least to engage meaningfully in the digital experimentation the moment seemed to demand; this long roundabout path to electronic literature was interesting because by the time I ended up in the Faculty of Fine Arts, I was so interested that position—in being able to [see] what being a professor in those spaces could accomplish and in being able to teach people the things that I had to struggle so hard to figure out “how do you make that happen?” Even when there was the opposite—people who just wanted to make aesthetically pleasing stuff—I’d ask “what is your story?” Or “how does this work theoretically?” Or “how is this political?” The moment you bring together the digital and storytelling, and the aesthetics and the interface, you’re building a kind of thinking machine.

L.F.: It’s interesting to talk about making before “research-creation” and “critical making” were considered accepted practices in academia. I want to rope in what you were saying earlier about the room in which you had all the paper and string, trying to figure out how all these things connect. There’s a hapticity that you had with thinking of language and ideas in terms of interaction and objects that I think is really cool. The act of actively connecting words together with string—literal string or a stringing together lexia—reminds me of making in terms of domestic labour and how we validate that as a form of making. It could be sewing or clothes making, mending, or being crafty and doing crafts. I don’t think it’s an accident that a lot of these forms of labour are actually mediated in early e-lit: Shelley Jackson’s Patchwork Girl (1997) connoting patchwork quilts, and more recently Christine Wilks’ Fitting the Pattern (2008) and Anastasia Salter’s Re:Traced Threads (2019).

C.F.: We also have Gail Vanstone’s work coming out of my AR Lab [at York University]—a feminist quilting project in AR. And a lot the time in that room full of string was very indebted to games of Cat’s Cradle and its feminist offshoots—tactile, potentially collaborative, hand-to hand, accessible … My lens for e-lit has always been through feminist practices of knowledge production. [When I started,] I don’t even know if hypertext 2.0 was out. Back then, we looked at [Italo] Calvino, Joyce … it was all male authors. Meanwhile, I was like, let’s look at Zora Neale Hurston. Let’s look at quilts. Let’s look at practices of femmage. Let’s look at Trinh T. Minh Ha. I was really influenced by feminist quilting, by practices like that 1970s womb room, all string—these incredible rhizomatic structures. And I made those structures—quilts and collages and sculptures—both for the fun of it and to enable me to think new things.

My initial response to entirely machine-crafted texts was really to resist and step more firmly into domestic literatures, into—you talked about haptics—very conscious forays into feminist making … concrete objects alongside the digital … handheld stories, concerns around the body, around confessional literatures around private, subjective moments rather than making a claim for universal language and a clean machine. Messy, intuitive, rococo. I see myself very much in the tradition of what was happening with feminist theory anyway, and seeing my working in electronic literature as really a direct line from feminist theory production into this.

L.F.: The return to materiality and embodiment through this term “domestic literatures” reminds of me conversations happening in the field of New Materialism around materialism and femininity, a lot of which is about thinking about materiality and matter. We would use your work as an example: the photo album in 200 Castles (2014), the family trinkets in Circle (2012), the pop-up book in Andromeda (2013)—things that you have to interact with to draw out the story and that you can’t forget have a body. I think something New Materialists would say is that women are not allowed to forget that they have a body. To also not consider the bodies of domestic literatures, domestic labour—very unseen labour—it’s privilege to be able to forget about those bodies. Do you have any more plans for different types of domestic literatures, or maybe embodied or haptic projects that you are thinking about putting out in the future?

C.F.: Totally. In many ways the room-scale VR work I’m doing right now makes it impossible not to ask – where is the body in relation to this world I’m making? What does it feel like to walk through this story? But I’ve also always been interested in the desiring body … what do we yearn for? How can I make someone want, through words? I also really like material objects … I like touch and weight and connected to haunted things. I like collecting and the digital makes that compulsion worse! It’s also familiar—I inherited thousands of objects … 17th century miniatures, 19th century bisque, memento mori hair broaches, ephemera, doll houses, tin toys, a hundred tiny fans—from mother. She told the story of her life through objects … what she hunted, what she wanted, what she loved, the arrangements she made… from the time she was a late teenager all through her life. One of the things I bought for the lab recently was an Arctic Leo scanner to scan them all for a VR project called The Doll Universe, because if I ever donate the collection I still want to be able to inhabit it—well, my father wrote books, my grandma wrote books … words are mostly easy to inherit. But being an executor to this very special world of things is a bit different—and my mother actually left this narrative of the way she made meaning of the world through these objects.

Some of the dolls that Fisher inherited. Source: Caitlin Fisher.

I think it’s not coincidence that they’re mostly also small domestic objects. Tons of ephemera from the early 18th century, so much needlework from 1812, from the 1780s. A lot of these are domestic. I do think of collecting as a consoling practice. What does it mean to build this world? I think of it very much as a storyworld that I have here, so one of my impulses is to digitize it and create a universe in VR. There’s something about small things that you control that I’ve always liked … to have AR in your hand … but I’ve also liked throwing artefacts into the trackers and making small things gigantic. To have them as these inhabitable worlds. I guess that’s a standard dream of childhood, right? Making a world and then jumping inside it. If I could have a superpower, it would be the power to miniaturize. And I guess the technologies in my Immersive Storytelling Lab kind of does that … digitize, shrink, reconstitute, defy the laws of physics. I like the idea of bringing really high tech to these domestic objects. I like storytelling through them.

There’s a linear narrative through most people’s impulse to collect. In my case, coming at it from an e-literature perspective, thinking about it as wanting to have a snap of the universe, but also to change that in the question: what happens when you walk through somebody else’s world? I think that’s very much the origin of most fiction.

More of Fisher’s inherited items. Source: Caitlin Fisher.

L.F.: I love this phrasing, “a snap of the universe,” as a description of your style of writing, but also as language around your interests and the way you see things. In observing parts of your mom’s collection [in our video call], some could describe those objects as tchotchkes, but they are active things, vibrants. There’s a thread that comes through them, within and among them, a relationality of objects to each other.

C.F.: [laughing] The tchotchkes in that cabinet are gold, but whatever. Yes, objects can connect and resonate in powerful ways. So can our stories. The observation that women’s stories cannot be universal, that they cannot matter universally, that the attention to the things that are private life rather than public life are the stories of indulgence in the culture … How do you make sense of the world if not starting from your story and starting to connect it politically with others? You don’t change the world through thinking that your story is not important and through accepting universal stories. So it’s a politically courageous act to disavow the dominant narrative of the culture. This is how change happens. It is kind of [wild] the change making that women do by saying, “Hey, hang on. That’s actually not what happens in my part of the world. That’s actually not the story of the whole culture.” There’s a political expediency of dismissing that as trite, that if you want to focus on yourself that is totally parochial, crappy writing, and not of interest to real people. And it’s obvious now—I’m at a point in my life where it’s super obvious that it matters when you tell people that the stories of their lives are not important.

L.F.: Yes, and very much connected to those feminist traditions in which you were trained. In fact, your practices could be and have been described as aesthetic feminist practice. In considering what it means to make e-lit with a political intention, as a close reading, I’m thinking about other types of aesthetic practices for what they could lend to a feminist undercurrent of your work—not just smaller stories, but how those stories are counter-narratives, political, resistant—I’m thinking about those in terms of aesthetic. That comes through in how the technology works. In Circle, for instance, while moving from physical section to section of stories from three generations of women, sometimes the voices overlap. In watching videos of this work, I try to focus on one voice at a time to hear what specific voices are saying. At some point, I realize that maybe I have to embrace the voices as they overlap.

Images from the e-literature work Circle (2012). Source: Caitlin Fisher.

C.F.: If you didn’t have to rely on video documentation, you could also at let them sound fully. A lot of this documentation is to show that both of these modes are possible. I kind of like the cacophony. In a lot of my work, there’s an overlap where maybe you can’t hear unless you are being super attentive, so the actual interactivity is to bring it close for spatialized audio, so you can also isolate those sounds. Or combine them.

L.F.: Having that ability to understand individual and collective voices is a big part of that. I also wonder: do you have any comments on the ways in which visual glitches might work in some of these projects? It doesn’t have to be Circle, but could be in works where I’m trying to lock into something and there’s a flickering that occurs. How do we read the glitch in your work?

C.F.: There’s a long tradition of experimental work that relies on the glitch and it would be wrong for me to say that I come out of that exact tradition, but in starting the AR Lab, I found I had to let myself love the glitch because a lot of that early work was super glitchy.

The biggest glitch was probably Andromeda where we couldn’t fix the software in time to stop the cacophony of overlapping audio files, so it ended up being very much like a choral poem though it had been written and designed so that you could hear every word. The idea that it just started overlapping and that very soon, all my character’s voices were drowned out—at first, it was incredibly annoying to me and I was committed to fixing it so that women’s voices would sound fully and you could hear them all. It was also a poem and I was being a bit precious. But I relaxed and played with the result and loved it, in the end. It actually changed the way I worked, because though this happened accidentally in Andromeda, it’s something that I sometimes consciously reproduced later. Now I see the glitch, the accident, the broken thing, the detour as a gift.

Oh. I did do it in Waves. At the time I was writing it, it was really difficult to get video and audio into HTML and have it stream properly. There’s one stream, the piece about “I don’t feel what running boys feel, only this wave of girls” that is kind of the signature piece, that is divided into about 20 different audio files that all start playing at once, so you can’t actually pull it apart. It’s not like I had never done it consciously. This idea of the digital being amenable to cacophony [offered] simultaneity in terms of the architecture of the writing, but also just to how that’s concretized in the listening or the seeing.

L.F.: Right now [in December 2020], I am teaching These Waves of Girls as a dynamic piece for the last time, it seems, as Flash will no longer be available as of December 31, 2020. I know that I’m spending much of my December recording and archiving some of my favourite e-lit works. What will the end of Flash mean for your earlier works and their archiving and preservation? Have you looked into ways that e-lit students and scholars can access these important canonical works?

C.F.: It has been exactly 20 years since I wrote that work for the ELO prize [for Fiction in 2000]. I wrote it in response and as a reaction to my doctoral dissertation. I defended in late June, I started my first academic post in July, and then I think the deadline was December 31st for Waves. I’d always thought that if I had time, it would have all been in Flash. Glad I didn’t! I actually looked a couple of weeks ago: the whole front is in Flash, which renders it inaccessible if I don’t do anything [to change that], but I realized I can probably just put it into HTML5, it is fixable for Waves because so much of it is HTML and tables.

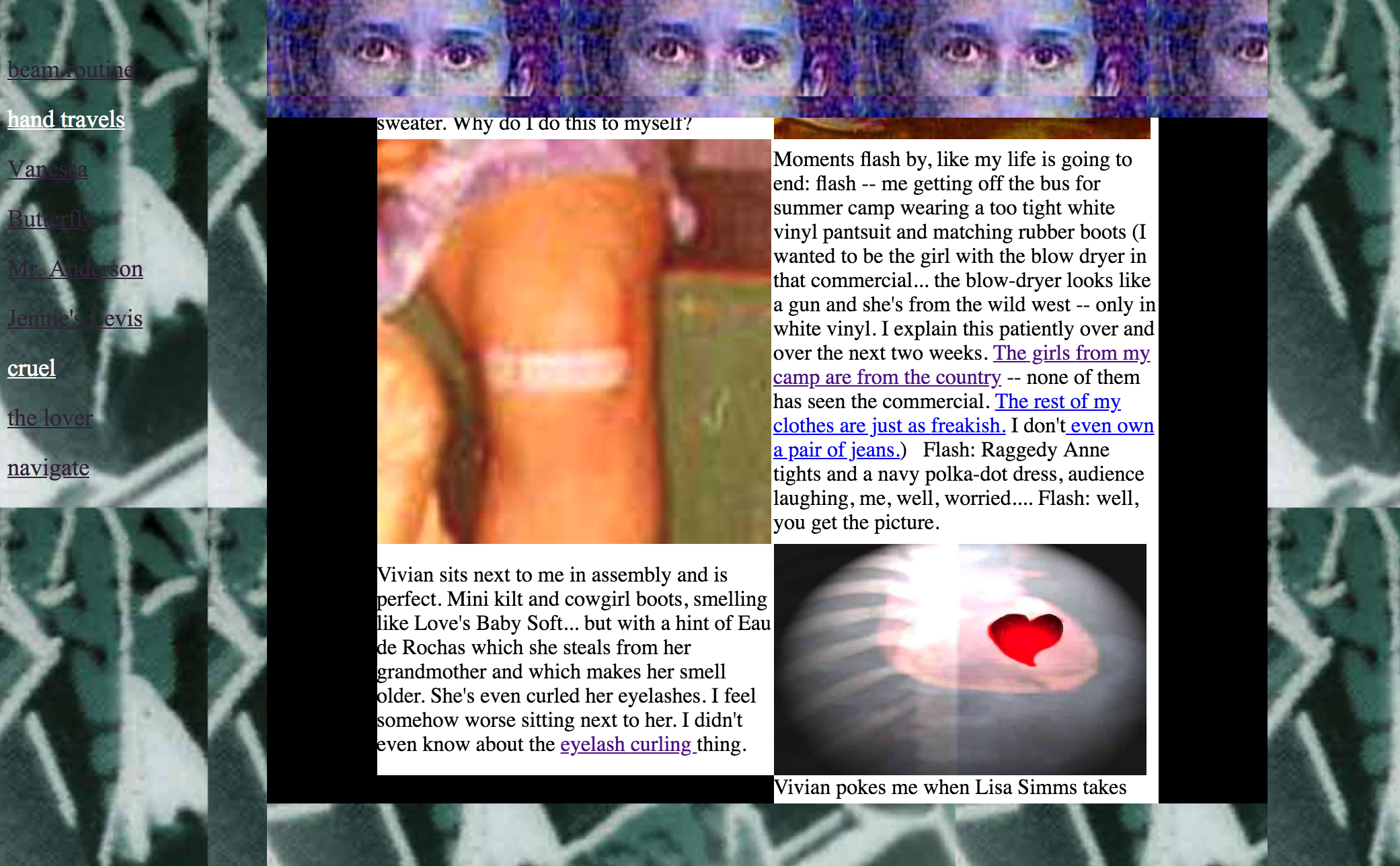

Image from These Waves of Girls (2000).

Part of this isn’t so much that these kinds of works can’t be translated. But there is a difficulty of going back to early works and putting energy there rather than just writing the new. But Waves—I was thinking maybe in honour of its 20th anniversary, I would maybe at least re-do the table of contents. I don’t know what kind of experience it would be for all the other small Flash things inside it.

It’s hard to look back on early work. I’m not that same person who wrote it. There is a kind of pulsing feminism to the work generally that comes from circumstance.

That is a hinge to the work and I’m sure it’s not unrelated to being a woman in the academy at a particular time. It’s also about having access to certain ways of working and ways of knowing that some people weren’t interested in.

I still love the idea of bringing small stories and unpopular poems into collision with the academic cultures I inhabit, changing things. I remember talking about feminism and materialist practices at a conference on a panel with Jessica Pressman and Kathi Berens on feminism and e-lit. And I remember coming away thinking much harder around what it means to have a million-dollar infrastructure and putting it into the service of experimental poems, coming out stories and tiny haunted domestic things? It’s hilarious.

When I started I felt that the emerging field of e-lit hadn’t yet captured the contribution of its women writers and that there were many unexplored and under-theorized and even neglected artistic and theoretical contributions that could help us make sense of the field and also inform what could come next. That’s where I intervened. So, part of the impulse of my doctoral work was to ask: why are there so few women when we start to talk about these contexts, when we think about the knowledge domain in which we’re considering electronic literature residing?

I still think that’s something I do. The space I inhabit. To make sure new tools have this knowledge and magic embedded in them. I pride myself by wanting [to respond to the question] “well, what do you want to do with your new, incredibly expensive facility?” at least in part with “I’m going to write tiny erotic stories of women’s lives that are super particular and hope that they have resonance.” Both the theory and both my own experience of reading suggest they do. And people write to me about those tiny stories all the time. And those stories are inside the software we make in the lab, the interfaces, the experiments in AI and the way I think about very specific bodies moving through a fogscreen.

L.F.: I think those tiny stories are needed, especially because they go against a lot of what is expected of giant infrastructures—institutions that often produce giant projects that want to fix the world and forget about tiny subjectivities.

[ … ]

L.F.: I wonder if you have any comments on how digital storytelling and/or e-literature then thinks about itself as an alternative to print-based publishing, especially in Canada? Is there something unique going on with e-lit in Canada or e-lit compared to other forms of Canadian writing?

C.F.: I spent my entire career sort of not being part of the traditional Canadian literary scene. Being very much on the outside. I have a career where I write and talk and give readings mostly outside of traditional writing circles in Canada, expect in the case where I’m asked to speak about publishing futures. I don’t know [if in a] parallel universe, if I would have in the absence of discovering hypertext in the late nineties and in the absence of being fortunate enough to have this other path, whether I would have maybe tried to be part of the traditional Canadian literary scene. I think traditional publishing with its particular political economy and gatekeepers is a difficult road. Electronic literature challenges this model in so many ways, and good work has new pathways for finding audiences, if not paying ones. Hence all the academic sidegigs! But I also see this changing. And in e-lit the people who love words often also love code and moving image and immersion. We can experiment with duration and scale and granularity outside the constraints of print.

I also think there are consequences to e-lit being formalized as a field in Chicago. It meant that the first things you did as an e-lit writer, even a Canadian one, were international, rather than local. And I know that receiving recognition for e-lit in the U.S. made a difference to how my work was understood, at least inside the university.

There are so many strong digital writers in Canada. Canadians have such a presence in global e-lit, but it doesn’t seem—except in this moment when I’m talking to you and you’re doing this issue [of electronic book review]—very rarely in my experience has it felt to me as if electronic literature is considered CanLit. I don’t have a sense that there is a strong argument being made outside of electronic literature circles that [digital poetics are being represented as] a part of Canadian strength.

L.F.: Well, if there is potential exclusivity to traditional printing and publishing platforms in Canada, might e-literature offer alternative forms or dissemination platforms for our writers and practitioners?

C.F.: Oh, definitely. E-lit writers are so often their own publishers. And the expressive tools we use for writing and our networks are also strategies for dissemination. We can target work for specific audiences on specific platforms. We can archive our work in central directories that are increasingly attuned to diversity and what it means to tell foundational stories of a field. E-lit exceeds geographic boundaries. And can also be crafted iteratively with media that is already in people’s hands every day … TikTok e-lit, mobile.

It’s interesting: I know just from talking to you that almost all of my touchstones for influence seem to have been either e-lit or theoretical texts, or particular kinds of visual arts practices of the 1970s. I haven’t really talked about print writers in influence, but I think that really has to do with the origin story of my writing. There are ways in which being able to take on digital writing has changed those origins. In 2000, the ELO prize [for Fiction] was a super significant prize. In the absence of those kinds of [opportunities], I might not have given a thought about e-lit as being a place where there was a community of readers and writers. It was actually a fantastic community for me, people who were really interested in ideas, in language, in the affordances of computing. But it was very different than the print publishing community: different people, different concerns, and different money. We really don’t have commercial e-lit publishing houses. These all have to be subsidized somewhere else, which is not unlike the reality for most poets I know. For a while my lab had a press, Futurestories Press, particularly focussed on augmented reality works.

In the last seven or eight years, there’s been a lot more interest that I’ve found from publishers. Publishers will get into spaces that have been traditional e-lit spaces, with more and more AR publishing and VR publishing. I don’t know the political economy of how that’s going to shift. Print publishers are more risk averse, of course. This is an area where practitioners of electronic literature could lead. We are already building the audiences of the future and often responding to the audiences of the moment. There are a lot of ways that, even if people are just imagining transmedia tie-ins, children’s books, then partly, e-lit will change the industry. The e-lit community has decades of experience and deep roots in both experimental and more mainstream writing. We know about co-creation. Many of us write at the intersection of performance and design. And we already witness a future for the CanLit beyond the book.

L.F.: Speaking more about the Canadian landscape, I have another question about your origin story as it links to Canadian figures. If I recall correctly, you had the opportunity to do work with the late Ursula Franklin, a renowned physics and technology scholar at the University of Toronto. What lessons did you take from the independent study that you did with her—for instance, perhaps on the social and political effects of technology? Did this time with Franklin shape or inspire your work in literature or media arts?

C.F.: There were a number of amazing people that I encountered at U of Toronto. The other person I did an independent study with was Rosalie Bertell, who was also incredible. Ursula Franklin was the nominal supervisor for one of my senior projects in undergrad that I wanted to do in Museum Studies. So that will tell you a little something, right? All of my things, the museum and the material—I was trying to come up with an angle with her.

First of all, she was so smart and so amazing. She concretized and embodied so much of what I was imagining of being an ethical feminist in the world and of being a scholar. I [had] total admiration and really knew her not at all, but she helped me to hone my project around thinking about materiality. I was coming from Museum Studies and was also an Economics major—

L.F.: —you’ve had a million lives! [laughs] This is why we need a time machine, to explore the alternate universes. Pardon me for interrupting.

C.F.: I did do my degree in Economics from U of Toronto, but I was very interested in material objects, so getting this independent study [with Ursula Franklin] got me a little bit away from macroeconomics.

She was incredibly helpful in thinking through material culture, and her support in shifting my skillset to material culture—even though that wasn’t the [original] trajectory—really did change the way I understood myself as a thinker, and in some ways gave me my material practice. I would imagine that it’s one of the hauntings in a lot of my work that goes back to wanting to make these tiny museums, to have these old objects, to have things that resonate between the physical and the story world. L.F.: I probably didn’t come across this way of thinking about materiality until the late 2000s and early 2010s, when it seemed to be starting to come into vogue. So, hearing that you were thinking about this in your undergrad—clearly, Franklin was ahead of her time—

C.F.: —she was a material scientist!

L.F.: Yes! When I started being interested in materiality as part of my PhD examination of book materiality, it completely changed my relationship to how I understood media.

C.F.: I think my entire house could be a book. As I walk through it, everything is an associated story, everything’s a spatial hypertext for me, and I curate and create environments that basically could be books. Something like Cardamom of the Dead (2016) is this expansive universe that riffs on a cassette tape from my 18th birthday. The first VR component is just called ‘Everybody at this party is Dead’ because they all are now. It’s bittersweet to start with those party voices. I also had an old tape from an aunt who was in her nineties talking about a fire, and also, there is a murder through it. I love VR’s infinite canvases and there [may be] a temptation to fill those. Again, about the museum and the material, I do like to fill space with objects and then create stories across them builds these story worlds. Many times, I think I’ve just made too many of them and I know people don’t explore all of these spaces. They’re too long, I know. But sometimes I like to think I’m writing for future forms – a time when the headsets aren’t too heavy and don’t make us dizzy. I also love the idea of long-form AR novels spread across the entire city, the world. AR is in many ways the perfect medium for someone who loves the digital but also wants to put something in your hand, or have you feel the wind on your face while she whispers.

If I have an avant-garde moment, that’s it: what does it mean to write for literacies that aren’t there or for technologies that have not quite caught up? I think Cardamom has 18 VR spaces, and its granularity is super short because people get nauseous because we haven’t fixed latency. There’s actually a hardware problem, but ten years from now, all of that will be fixed, and there won’t be any problem to go through a novel-length VR work. Most of what I want to do in AR is imagined for a moment when we have decent optical see-through headsets or AR contact lenses. I have so many stories that just can’t be experienced the way I want them to be, not yet. But soon.

L.F.: You’re asking the question of what it means to write for literacies that aren’t there—we’re talking about you as a storyteller, but we’re also thinking about the alternative purposes of what your works may have. As you describe your work, some of it seems to be an archive. Works and parts of works don’t necessary need to be read, but they are left there as a trace, a museum, a built world.

C.F.****: I do agree with “archive,” but what I’ve always loved about hypertext or associative mapping or being able to link is that I’m not just leaving a person in a room. All of the things can actually talk, but also the web of associated structures create arguments across different places in an arc. It’s not just curatorial. Not just that things are left in this space and if people visit them, a million different stories or ideas can [come out of] them, even if that is maybe also true. But, while my practice is archival to a certain extent, what I’ve been excited about in terms of the capacity of the digital is for me to at least take you by the hand and say “this one went with this one,” “this one goes here,” “this is what happens when these three go together,” and “this is what happens when the whole room implodes and becomes something else.” The ability of leaving a trace of the way that I tell the story of the archive is still where I think the literary and the archive meet [with] the digital.

Interactions with the haptic e-literature work Circle (2012). Source: Caitlin Fisher.

L.F.****: I really love having your own trace among the found things, because I think it presents an alternative to the ways in which people might otherwise think of archives. It’s not like a Foucauldian archive, which is all history and ideology and power. It’s not a Kittlerian archive necessarily either, in thinking about the archaeologies of the objects. Maybe you’re shaping a new form of archive that’s much more interactive in its storytelling.

C.F.: I never really thought of it as archive so much, but the other big influence on me was [Theodor] Adorno. A big touchstone was me was [a quote of his, in which he describes] theoretical thought not being unlocked by a single key, but being unlocked by multiple keys.

That’s how I understand the capacity of early hypertext, but also the digital now. There’s something about creating these constellations of thought that is still something I want to do right by at some point: there’s an incredible capacity to create thought-sculptures if you leave the philosophical line. If you have the sculptural form of all the associated things in your head, you will eventually come down to the thing. And digital literature makes it possible for you to concretize these sculptural forms and share them. When I pass an e-lit constellation to you, it’s back to cat’s cradle. A feminist proposition. Desire. A theory machine. I pass the form to you and you can actually inhabit it. But not like an empty building. I’ve left breadcrumbs for you. Or given you my hand. String.

I’ve always been really struck by that [idea] that we don’t unlock things with a single key, we unlock them from multiple areas. That’s the power of the digital and the power of the spatial. It’s how thought is activated. Why wouldn’t you, living in this moment, want to write this way?

Acknowledgements

Lai-Tze Fan would like to thank Caitlin Fisher for agreeing to participate in this conversation, as well as for generously providing images from her personal collection of work and inherited items.

Cite this essay

Fan, Lai-Tze and Caitlin Fisher. ""A Snap of the Universe": Digital Storytelling, in Conversation with Caitlin Fisher" Electronic Book Review, 7 February 2021, https://doi.org/10.7273/2axc-bc12