Against Information: Reading (in) the Electronic Waste Land

Andrew Klobucar argues that a new iPad app for The Waste Land demonstrates, despite the developer's intentions and Eliot's fears, that the symbolic form of the database is irrepressible. According to Klobucar, Eliot bemoans the cultural impact of new media and technological innovation, though his poem--particularly through Pound's editorial notes and Eliot's added annotations--employs the structure of a database. The app for The Waste Land attempts to mitigate this tension by promoting a sing...

Andrew Klobucar argues that a new iPad app for The Waste Land demonstrates, despite the developer’s intentions and Eliot’s fears, that the symbolic form of the database is irrepressible. According to Klobucar, Eliot bemoans the cultural impact of new media and technological innovation, though his poem—particularly through Pound’s editorial notes and Eliot’s added annotations—employs the structure of a database. The app for The Waste Land attempts to mitigate this tension by promoting a single legitimate version of the poem, though the app’s structure ultimately works against that model, as it frees readers from the imposed authority of singular narrative.

Touchscreen devices, with their capacity to combine the computing power of desktop platforms with the level of accessibility provided by mobile networks, seem particularly emblematic of electronic culture’s overall association with ideals of progress and innovation. At the same time, these technologies offer a distinctly conservative, almost reactionary challenge to late 20th century understandings of the human-computer interface as an advanced typographic environment compared to more traditional, print-based modes of communication. Open the iBooks app on Apple’s iPad screen, for example, and the viewer immediately faces an image of a pale, wooden bookshelf, upon which are laid his or her most recently downloaded print works. An additional brush of the index finger over one’s choice of book icon brings to the screen the full, pixelated replica of an open codex, pages ready to turn from one cover to the next as the physical act of print-based reading is flawlessly simulated before our very eyes. Conveniently hidden from the reader’s view is all reference to coding or programming as a linguistic activity where information is, in fact, engaged at any level in a symbolic activity – never mind a specific programming practice.

In this way, the iPad helps to re-form our relationship to electronic media, somewhat deceptively and regardless of its content, as a referential mode of representation. In other words, reading or viewing media using a touchscreen interface tends to re-situate such practices as physical activities first and cognitive ones second. One does not cognitively engage with media via these latest advances in screen-based interfaces so much as one physically interacts with it, while the screen itself, along with the media forms it suggests, function like any concrete entity or body to be handled and engaged accordingly. It functions as a musical instrument to be played as a keyboard, perhaps, or even a string instrument, if chosen and opened as such. In short, most users of a touchscreen device like the iPad will find themselves hard-pressed to discover they are in fact engaging with any kind of programming or language-based activity.

It is exactly this attribute of symbolic variability and plasticity, however, that throughout Modernist thought and writing has been habitually associated with attitudes of anxiety, if not terror. Rilke’s celebrated opening complaint in The Duino Elegies continues to haunt the annals of high modernism as an exemplary reflection on the sweeping cultural transformations associated with European civilization at the beginning of the twentieth century. In his first elegy, the poet offers only a plea for help concerning the post-Aristotelian uncertainties of aesthetic inspiration, presenting beauty itself as “nothing but the beginning of terror.” Rilke persists,

Each single angel is terrifying.

And so I force myself, swallow and hold back

the surging call of my dark sobbing.

Oh, to whom can we turn for help?

Thus we have one of the more formative images of western culture’s entanglement with the new political, economic, and intellectual realities of modernity. Proust, too, described the sensual appreciation of an artwork as nothing short of “traumatic,” likening a modern aesthetic experience to a kind of break or rupture in consciousness. The most exemplary literary works featuring this attitude of ideologico-historical crisis are likely T.S. Eliot’s contributions to the Modernist canon, as can be seen as early as in The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock (1917):

It is impossible to say just what I mean!

But as if a magic lantern threw the nerves in patterns on a screen:

Would it have been worthwhile

If one, settling a pillow or throwing off a shawl,

And turning toward the window, should say:

“That is not it at all, That is not what I meant, at all.”

Eliot’s language means to invoke on one level a strict ethical concern over the declining social impact of poetry (and the high arts in general) concurrent with the beginning of the first world war and the emergent mass culture of the early twentieth century. Yet, while the focus of his disquiet seems located first at the point of speech – the poet admits the limits of his voice (“It is impossible to say just what I mean”), an equally engaging comparison emerges between Prufrock’s drive towards verbal lucidity and his audience’s increasingly enthusiastic encounters with its “magic lanterns” and “screens.” Placed where it is in the poem, the pairing seems, for Eliot, particularly emblematic of his larger conflict with language as a medium of technical innovation, rather than a way of preserving historical and cultural continuity. To Eliot’s umbrage, these screen patterns underscore what his words continuously fail to do – achieve some measure of cultural significance, even though the level of meaning associated with them can seem trivial at best. Cast in the shadow of popular media’s growing capacity to tantalize its audiences with chaotic swirls of incomplete thoughts and emotions, poetry, Eliot suggests, too often seems content to offer little but patterns and affect as opposed to any concepts of consequence.

Eliot’s well-debated ethical anxieties over the metaphysical shortcomings of modern culture are formative in the development of a particular lineage of Modernism. Understood in this context, Eliot’s poetry summons an early anti-aesthetic literary complaint against what he likely saw as the confusion of technology-inspired rationalizations of visual schema for authentic, creative insights. Even today, new media technologies tend to inspire poets and artists to adopt Eliot’s conservative stance by comparing advances in digital visualization tools to updated versions of the “magic lantern” throwing nerves in increasingly detailed “patterns” on screens of higher and higher resolution.

Eliot is critically aware throughout his work of the implicit, almost existential terror accompanying nearly every technological challenge to cultural traditions and habits of thought. In the opening stanza of his liturgical play The Rock (1934), he asks,

Where is the wisdom we have lost in knowledge?

Where is the knowledge that we have lost in information? (1952, 104)

The two questions imply in a kind of reversed syllogism both a hierarchy of modern epistemological forms and a general critique of the modes of reasoning that derive from it. If knowledge is not equivalent in value to wisdom, and information of still less value than knowledge, then it would seem accurate to deem information’s relationship to wisdom as especially fragile. Suddenly modernity itself, being premised upon the accumulation of information over a priori beliefs,becomes seems equally identifiable with the loss of wisdom. Not only can knowledge, and thus information, not produce wisdom, it would seem that the more one is invested in the former, the less access he or she has to the latter. To be modern, in other words, is to forfeit the very possibility of wisdom.

The play’s Christian theme clearly aligns modernity’s information-driven epistemological decline with the loss of religious authority in western culture. AsThe Rock progresses, the Chorus summarizes for the audience the two most important Christian events, namely the creation of the world and the incarnation of Christ, and then promptly and formally grieve the modern progression of atheism:

But it seems that something has happened that has never happened before: though we know not just when, or why, or how, or where.

Men have left GOD not for other gods, they say, but for no god; and this has never happened before

That men both deny gods and worship gods, professing first Reason,

And then Money, and Power, and what they call Life, or Race, or Dialectic. (1952, 108)

In Pericles Lewis’ reading of the play, the central conflict remains theological in nature, following what he describes as a persistent concern in Modernist culture over what was for many artists and writers a transformative moment in the social and political role of faith (2007, 20). Modernist thinkers seemed critically interested in what Lewis calls “religious inclinations,” reviewing aesthetics as a kind of framework for exploring the transcendent in both culture and human experience. Eliot’s obvious concern for declining structures or vehicles of faith in modernity certainly compares to themes and questions on the sacred introduced by novelists like Henry James, Marcel Proust, Virginia Woolf, and Franz Kafka, among others, though Eliot’s turn to religion was far more explicit than these other writers (2010, 5).

At the same time, we can also take Eliot’s apprehensions in the play quite literally and interpret them in part as an explicit critique against modern culture’s misplaced dependence on information - labeled here as “Reason” - to provide both a method of interpretation and a basis for understanding one’s surrounding world. It seems significant that its flawed epistemological function is grouped with “Money, and Power,” as well as “Life, or Race, or Dialectic” to form the top false sources of modern social meaning and value. Lewis is right, of course, to qualify Eliot’s critique as ultimately a protest against atheism, yet the precise issues being examined remain economic, political, biological, ethnic, and social insofar as the way in which reason is able to transform how the modern individual makes sense of the world around him or her. Modern reason, Eliot contends, repudiates any hope for a holistic understanding of reality, not just by repudiating theological belief systems, but by emphasizing an innately divided, multi-categorised framework of knowledge in general. Understanding the world is tantamount to partitioning it - abstractly sectioning it off into questions of economics, politics, biology, ethnicity, and social relations, to name the primary areas of analysis. But the specific categories or disciplines Eliot has chosen to feature are not as significant as the poet’s broader emphasis on the modern construction of knowledge itself as a mode of fractioning or ramification. Information-based reasoning abhors the whole. One understands the world only so much as one can divide it.Thus we are able to see through Eliot’s eyes just how the inherent function of data or facts at one level is to displace or disorient one’s relationship to the extant real. Theological debates aside, what interests Eliot here is modern culture’s ostensible development of a knowledge system that effectively negates any possibility of authentic, purposeful creative insights due to its inherently structurally divisive logic. Culture, so informed, whether via language or any other media format, thus evokes, at least for Eliot, a perpetual incapacity to function as a mode of perception or cognizance.

The work that most fully develops this critique is, of course, his vast 434 line dissonant and dark elegy to modernity, The Waste Land. Published in the late fall of 1922, the most commonly read version of the epic poem appeared with a complete set of notes and references in the United States under the imprint of Boni and Liveright. Eliot had previously published a more condensed version of it without any annotations in the UK in the first issue of The Criterion (October 1922), a new literary magazine he was starting and editing that year. The poem appeared next a few weeks later in the US in the November 1922 issue of The Dial magazine. The first complete UK book version appeared almost a full year after the Boni and Liveright edition in September 1923 when Leonard and Virginia Woolf’s well known publishing venture, the Hogarth Press, produced a private run of 450 copies, handset by Virginia.

The poem’s publishing history is significant to understanding some of the complex critical issues Eliot had concerning the cultural and social effects of an information-driven, technology-oriented political economy. While the most commonly recognized form of the poem remains its later book editions with notes and references, most literary histories of the work agree that this annotated version does not correspond to Eliot’s original intentions. As well, the re-discovery in 1968 of the original manuscript stored at the NYPL revealed for the first time in almost half a century just how significantly the project had been altered by Ezra Pound upon being asked by Eliot to review it in January 1922. Eliot had already sent the original version of the poem, pre-Pound’s amendments, to one of his patrons in New York, a lawyer named John Quinn. Working with Pound’s many detailed editorial comments and manuscript changes, Eliot prepared a much shorter version for its debut appearance in The Criterion. A still later edition of the poem re-published in 1925 and featured its famous dedication to Pound, distinguishing his role in Eliot’s professional life as “il miglior fabbro” - the better craftsman - a line taken from Dante in reference to the twelfth century troubadour Arnaut Daniel and noted by Pound himself in his study of the troubadour tradition,The Spirit of Romance** (1910). Only in 1968 would readers generally come to see just how complex and meaningful this dedication might be in the context of the poem’s dramatic transition over the early winter of 1922.

Following from this history, it seems accurate to identify at least two primary ways in which The Waste Land develops its critique of modernity’s information-centric culture. Across its five sections, the text is replete with images and descriptions emphasizing cultural fragmentation and discontinuity in a variety of contexts. Nature’s seasons arrive abruptly, almost violently, as Eliot famously describes the shift from March to April in the opening lines. Multiple voices reflect on events and perspectives in an almost ad hoc manner, fraught with anxiety and incoherence, denying the reader any central focus or premise. At the same time, these images of incompleteness artfully combine with an equally discontinuous mode of presentation to provide a kind of methodological critique of any coherence in format or structure.

To look more closely, albeit briefly, at the poem’s content, the season of spring, again as it is imaged in the poem as a sickly, almost violent state of transition between winter and summer, seems to function as a metonym for the process of creativity itself in the deteriorated condition Eliot understands it to be in relation to information and mass media. No longer its own activity, no longer, in other words, a process of power aligned with the irruption of life itself as an erotic, natural force of determination, creativity now suggests little beyond a momentary shift or perhaps disturbance between two seasonal limits – a nebulous “mixing” of “memory and desire, stirring / Dull roots with spring rain” (lines 2-4). Whereas beyond this liminal state, where process seems never ending, we find an unusual sense of comfort in the prior, less dynamic - hence better defined, more reliable – inertness of winter: a condition that “kept us warm, covering / Earth in forgetful snow, feeding / A little life with dried tubors” (lines 5-7). Eliot is right, of course, to convey such a devolved or reduced status of “creation” and creativity within the modern episteme. Acknowledging the covert terror in modern aesthetics of any sensory experience as yet unmediated via form or function, Eliot must consequently understand the implicit cultural rejection of creative practices for modes of innovation or invention. If an act of creation in neo-aristotelian terms can propose the capacity to produce something out of nothing, thus imagining void, not as an emptying of meaning, but its veritable source, no terror would emerge.

But we are agents of innovation here. The “different voices,” as Eliot labelled them in the original title of the poem, present together a still fascinating cacophony of narrative bits. The varying cadences, dialects, and personalities shift disruptively, even erratically, preventing any pretence to conversation or an exchange of viewpoints, however fragmentary. One of the first caricatures to appear emerges as a quick paced, first person account of an aristocrat’s summer reveries. Invoking a light-hearted, erratic tone, conjunctive clauses – “And went on in sunlight,” “And drank coffee” – tumble forward mechanically – “And when we were children,” “and I was frightened,” “and go south in the winter” - spilling aimlessly into a series of run-on sentences that do not so much address the poem’s readers as rush breathlessly past them. Before any narrative point can be gleaned, however, these fleeting memories, culled perhaps from the memoirs of a Duchess, are fully negated by a new tone: a dramatic, heavy-handed voice of enquiry shifts the poem’s focus, such as it is, wholly and abruptly from a voice of reminiscence to one of cold, quasi-metaphysical interrogation. “What are the roots that clutch?” (line 19). Again, pitted as they are firmly against each other, these voices do not suggest dialogue but signify instead disparate fragments arranged around even larger, more prominent silences. Foreshadowed as such, the gaps between narratives seem endlessly more significant, evoking an echo that at times seems louder than the words themselves, as if the function of the latter was merely to emphasize discontinuity; recall how information functions in the poem: as noted above, meaning occurs through assemblage. Void remains terrifying. Where an emergent will to bring forth once functioned, now there’s only silence; again, the complaint against language as a mode of creation noted in Prufrock comes to mind: “I should have been a pair of ragged claws / scuttling across the floors of silent seas.”

As noted above, two significant structural developments to have evolved out of the poem’s complex publication history are Pound’s edits, which effectively cut the poem to half its original length, and Eliot’s own subsequent addition of annotations and references to its final publication as a book. Both changes share the distinction of originating outside the author’s own personal literary aims regarding the poem’s presentation. Exactly how Eliot felt about Pound’s edits appears on record as overly positive. As Wayne Koestenbaum charges, “Eliot admitted that he ‘placed before [Pound] in Paris the manuscript of a sprawling, chaotic Poem’; in his hesitation to claim those discontinuities as signs of power, he resembles Prufrock - unerect, indecisive, unable to come to the point” (1989). Indeed, the poem effectively seems to cast the two poets into a symbolic relationship of power, perhaps gendered, with Pound providing the structural (male) support and coherence that Eliot agreed was lacking in the earlier, longer versions of the work. Upon working with Pound, Eliot himself claimed that his friend and editor never gave in to the temptation merely to re-write the poem according to his own vision, but instead “tried first to understand what one was attempting to do, and then tried to help one do it in one’s own way” (175). Yet, referring back to Koestenbaum’s comments, literary history tends to acknowledge Eliot’s overly passive relationship to Pound in this critical stage of the composition process. Certainly the resulting changes seem significant enough even today to qualify Pound’s work with Eliot as nothing less than transformative. In fact, were Pound’s revisions less substantial, the second structural amendment might not even have been necessary, for the added notes and references to the work came only at the request of Eliot’s U.S. publisher who regretfully informed in the fall of that year that the poem’s length of 434 lines were not quite sufficient to warrant an entire book. The annotations were thus added, primarily, Eliot admits in a later essay, to bulk up the publication’s overall number of pages.

Each of these significant editorial changes were ultimately approved and administered by Eliot; yet, in many ways, they illustrate a distinct set of conflicts with respect to the structure of the poem and its relationship to its primary themes. Paired with Eliot’s annotations, the poem’s 434 lines offer as much satire as elegiac lament, for the references Eliot adds encourage us to review the work, at least in terms of its structure, as an annotated study of 2500 years of cultural, philosophical, and scriptural writing. In fact, from this perspective, the work manages much more than a heap of broken images; it provides a veritable archive of prominent western intellectual references, built as a compendium of sources, ranging from Homer, Petronius, and Vergil to more contemporaneous academic sources like The Golden Bough: A Study in Magic and Religion by Sir James George Frazer and Weston’s work From Ritual to Romance (1920), organized, summated, and verified for public presentation.

To fully appreciate Eliot’s concerns over the role of annotation, one might refer here to Steve McCaffery’s unique study of what he calls the proto-semantic where he traces a history of writing’s development as exposition, with its complementary capacity to abstract and/or abridge notes of observation into more elaborate modes of discursive analysis from the pre-Renaissance before formal prose genres and disciplines of study eventually arose (Prior to Meaning 59).

I have written a more detailed summary of McCaffery’s examination of proto-semantic lineages in writing recently published in From Text to Txting (UP Indiana, 2012), where I look at how an historical understanding of annotation and poetics can help contemporary literary theory develop new teaching methods for the 21st-century classroom. It’s also possible to look more closely at recent critical work that extends this important, yet understated literary history of annotation into the digital era to include critical analyses of the poignant relationship between code and commentary offered by contemporary programmable media artists and writers like Stephanie Strickland, Nick Montfort, Mark Marino and Mez Breeze. Linking annotation as an important practice between print and electronic formats is a discursive tension between the conceptual object of study - the artifact or tool at hand, whether it be a code or poem, and its annotation or social distribution.

As these writers and artists working with programmable media make clear, a simple database environment begins to emerge both symbolically and literally as soon as one engages in any kind of dialogue with a text or textual object. In other words, what the database makes most evident, and, in fact, preserves, is an important discursive tension between whatever conceptual object of study is apparently at hand - the artifact or tool or device of discussion - and the annotations and commentary surrounding it.

Such a discourse remains especially vital to critical studies of electronic literature, since most works composed for digital distribution present themselves simultaneously as two very different types of linguistic structures:

- as programmable code, and

- as a separate media object or interface.

The significant, if underemphasized, gap between these two levels of writing and production is especially apparent in any electronic or programmable literary work, allowing authors and users alike to view each respective project as a working database of related functions, processes and media events. Arguably the relatively new, but growing study of critical coding practices is partly premised upon the structure of the database as the best visible framework to feature modes of programming alongside any specific, related set of processes or events. Within the database, neither one of these elements can be prioritized over the other, while at the same time they can’t be combined together to be interpreted as a single, holistic form or genre.

To interpret each of these dimensions of an electronic literary project (whether form or reading practice) as interrelated, though not equivalent, is to engage with the poem as a database. Accordingly, it is perhaps possible to compare Eliot’s own cultural conflicts with annotating The Waste Land at least partly to the broader disputes or ambiguities in meaning that underlie the very structure of the database itself as a discursive platform. When Pound and Eliot in the early winter of 1922 sat down in Paris to re-shape the latter’s original manuscript into the shorter, more formally consistent work we now have, a cultural object - much like Eliot’s vision of spring in April - was simultaneously destroyed and constructed. Eliot’s later dedication of the poem to Pound as il miglior fabbro does not with any accuracy call him a better “poet,” though many quick references to the phrase tend to qualify it as such. If Pound, in Eliot’s eyes, is to bear the honor of il miglior fabbro, it is most likely a reference to his skills as a better craftsman or artisan - a writer, in other words, able to focus on the more technical aspects of a text and its meaning. Hence, il miglior fabbro sees Eliot’s poem in a way that Eliot himself surely hesitates to consider fully: namely, as a distinct linguistic object or structure implicitly open to multiple modes, multiple of levels of engagement. Of course, Pound would not likely have emphasized any such openness in the work, conceiving, as his cultural vision mandated, a prominent degree of cultural authority being innate to the object itself. However, Eliot’s poetics presumably aligned certain attributes of Pound’s formal or structural engagement with The Waste Land with many of the same key epistemological dilemmas that he associated with modern, information-based approaches to language in general. Evidence of language’s structural integrity at some level could only serve to underscore its incapacity as a medium to engage meaningfully or substantially with the world as is. Where for Pound, the form and materiality of a medium signified together new possibilities of cultural significance, for Eliot what remained chiefly valuable with respect to such structures derived, as suggested earlier, from their ultimate failure to signify anything resembling a deeper, meta-coherent sense of reality. From this perspective, a dual significance in Pound’s designation as the better craftsman suddenly emerges. Pound as artisan, as fabricator is thus a builder of both objects and objectivity, but at the same time, he evokes just as notably a barrier to the kind of wisdom and vision Eliot laments is lacking in the modern worldview. In becoming craftsmen and technicians, we may have opened the door to an array of new conduits of knowledge; yet, at the same time, we have just as surely impeded the possibility of ever communicating a more holistic sense of our reality.

In this way, any subsequent request for annotation - for commentary or discourse - with respect to the poem seems formally consistent with Pound’s edits; for both revisions highlight the text as a structure ready to be analyzed - a mode of reasoning plainly invoked for the reader as an archive of textual fragments to be engaged, processed, examined and then processed again, perhaps in perpetuity. What hope for any sense or understanding to emerge at some point from this type of framework obviously recalls both the structure and function of the database. Eliot’s annotations in combination with the fragments themselves effectively present, and in some ways even dramatize, many of the same characteristics associated with how modern knowledge itself has evolved as a discourse - which is to say, in terms of a framework of distinct media-based objects consistently, yet dynamically organized in relation to various modes and practices of interpretation.

For a fuller, in-depth study of the database, one might turn briefly to the media theory of Lev Manovich, for whom such a framework exemplifies what Erwin Panofsky calls a “symbolic form” - literally, a historically and culturally specific mode of mediating social perspective and interpretation. According to Manovich, the symbolic form of the database, and thus Eliot’s early literary interest in it, follows chronologically from the cultural apparatus Panofsky identifies as narrativity, which in turn developed from linearity - the conceptual framework that signaled the very beginning of the modern episteme. Manovich writes: “Indeed, if after the death of God (Nietzche), the end of grand Narratives of Enlightenment (Lyotard) and the arrival of the Web (Tim Berners-Lee) the world appears to us as an endless and unstructured collection of images, texts, and other data records, it is only appropriate that we will be moved to model it as a database” (“symbolic”). Such a history of consecutive developments in symbolic form may, in itself, appear too linear. While the database is easily more apparent as a working model of cultural perception, just as the Web itself may help us visualize “an endless and unstructured collection” of data, the data appeared just as unlimited in the print era, and the subsequent frameworks needed to archive and demonstrate it were just as important, if not almost as visible as any narratives. Manovich’s earliest examples of digital databases emerging into culture are CD ROM encyclopedias. However, the formal emergence of print encyclopedias in the 18th century suggests that the database has been an important symbolic form for the entire modern period, providing a conceptual framework for knowledge the moment it became information-based. Certainly narrativity is symbolically dominant within early modern culture, as is evident with the rise of late 18th and 19th century prose genres like the novel, the memoir, the political manifesto and even natural science essays. Hence, Panofsky is correct to emphasize the narrative as a key symbolic form where, contrary to the structural outline of a database, texts evoke a more continuous, sequential set of references disseminated via a single, distinct perspective. What discursive enquiries or points of analysis a narrative may inspire are very quickly pushed to the margins of the central text itself, to appear in the form of footnotes or endnotes. A narrative’s development is temporal, suggesting an almost evolutionary aspect to the form of later “corrected” editions of the original work.

Returning to Eliot and his own respective analytical and annotative work with The Waste Land, one can perhaps see better now how focusing on the materiality of the various poetic devices he uses in the poem similarly interrogates and thus de-stabilizes any assumed meanings or references to established intellectual traditions. Elements that may have once been considered both historically and culturally purposeful in and of themselves have been reduced to mere points of information perpetually open to revision and re-evaluation. Certainly, by turning The Waste Land into a kind of database in itself, Eliot must feel somewhat disconcerted to have shifted the locus of interpretation away from the poem’s textual fragments to tensions he himself has built between them and the myriad new contexts suggested via his marginal notes and comments. In some ways, given his uneasiness with the influence of data and information-based reasoning on poetics, it seems that Eliot would prefer to take us back to a point in literary history before the emergence of McCaffery’s proto-semantic lineage. At the same time, the poet also realizes that higher levels of authority and purpose cannot be re-introduced into the cultural fabric of Modernism without actively dismantling most its critical apparatuses and practices. Therefore, it’s tempting to interpret Eliot’s annotated edition of The Waste Land in part as a critique of such apparatuses and their complex relationship to both poetics and cultural history - especially considering the interesting set of structural and semantic conflicts they initiate throughout the poem. The 51 references Eliot provides, as noted above, at the publisher’s request to fill out the minimum content requirements for the book’s publication, offer together a flawed, even at times whimsical, use of citation and etymology. Often it seems that the primary purpose of Eliot’s marginalia is to reveal how easily such tools can be misused, resulting in permanently obfuscating a work’s cultural significance. In the case of The Waste Land, Eliot’s annotations, it seems, capably provoke any pretense a work might have to lasting serious argument or discussion. When, in his 1956 essay “The Frontiers of Criticism,” Eliot offers considerable regret for, in his own words, “having sent so many enquirers off on a wild goose chase after Tarot cards and the Holy Grail” (1986, 110), he is most likely referring to the note he added for line 46 of The Waste Land. The note itself is constitutes Eliot’s sixth formal addition to the poem and begins by admitting his own lack of “familiarity”

… with the exact constitution of the Tarot pack of cards, from which I have obviously departed to suit my own convenience. The Hanged Man, a member of the traditional pack, fits my purpose in two ways: because he is associated in my mind with the Hanged God of Frazer, and because I associate him with the hooded figure in the passage of the disciples to Emmaus in Part V. The Phoenician Sailor and the Merchant appear later; also the “crowds of people,” and Death by Water is executed in Part IV. The Man with Three Staves (an authentic member of the Tarot pack) I associate, quite arbitrarily, with the Fisher King himself. (Eliot’s note for line 46)

Similarly in line 68 of the poem, Eliot describes the sounding of the bells of St. Mary Woolnoth, keeping the hours “with a dead sound on the final stroke of nine,” and then refers his readers to the essentially meaningless annotation: “a phenomenon which I have often noticed” (note for line 68). It seems clear that Eliot’s aims with his annotations are not to clarify or even stimulate much discussion. He writes in the same essay, “I have sometimes thought of getting rid of these notes; but now they can never be unstuck. They have had almost greater popularity than the poem itself - anyone who bought my book of poems, and found that the notes to The Waste Land were not in it, would demand his money back” (1986, 110).

Reviewing Eliot’s significant anxieties over the cultural role of annotation and thus analysis itself as a method of interrogating, perhaps even destabilizing, socio-historical authority, we can (with some irony) see that touchscreen technologies may in fact disseminate this particular literary project more faithfully - in other words, with less of a conflicted relationship to the material conditions of production - than the printed book format he used in 1922. Specifically, it seems reasonable to consider the digital touchscreen’s technical capacity to subordinate some of the more discursive elements innate to databases for a more singular, perhaps even holistic sense of cultural history.

As contemporary readers of The Waste Land know, the poem’s first official electronic appearance, in fact, is in touchscreen format, though various unofficial hypertext versions have existed since the mid 1990s.See, for example, the compilation published as a tripod Website at http://eliotswasteland.tripod.com/ and Richard A. Parker’s “Exploring The Waste Land” Website (1997-2002) at http://world.std.com/~raparker/exploring/thewasteland/explore.html. Working with Faber and Faber, the London based software and media company Touch Press both programmed and released the 1922 poem as an iPad app in the spring of 2011. Not only does the iPad re-cast Eliot’s definitive modernist project as a less disparaging critique of cultural fragmentation across different media formats, the device’s well preserves Eliot’s persistent anti-aesthetic/anti-information efforts in his writing in order to preserve a more traditional cultural orthodoxy and sense of purpose for the digital era.

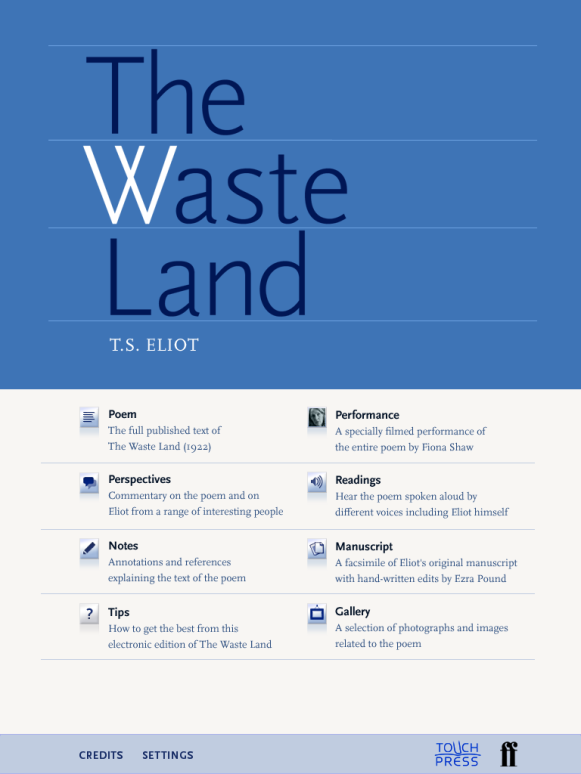

Figure 1

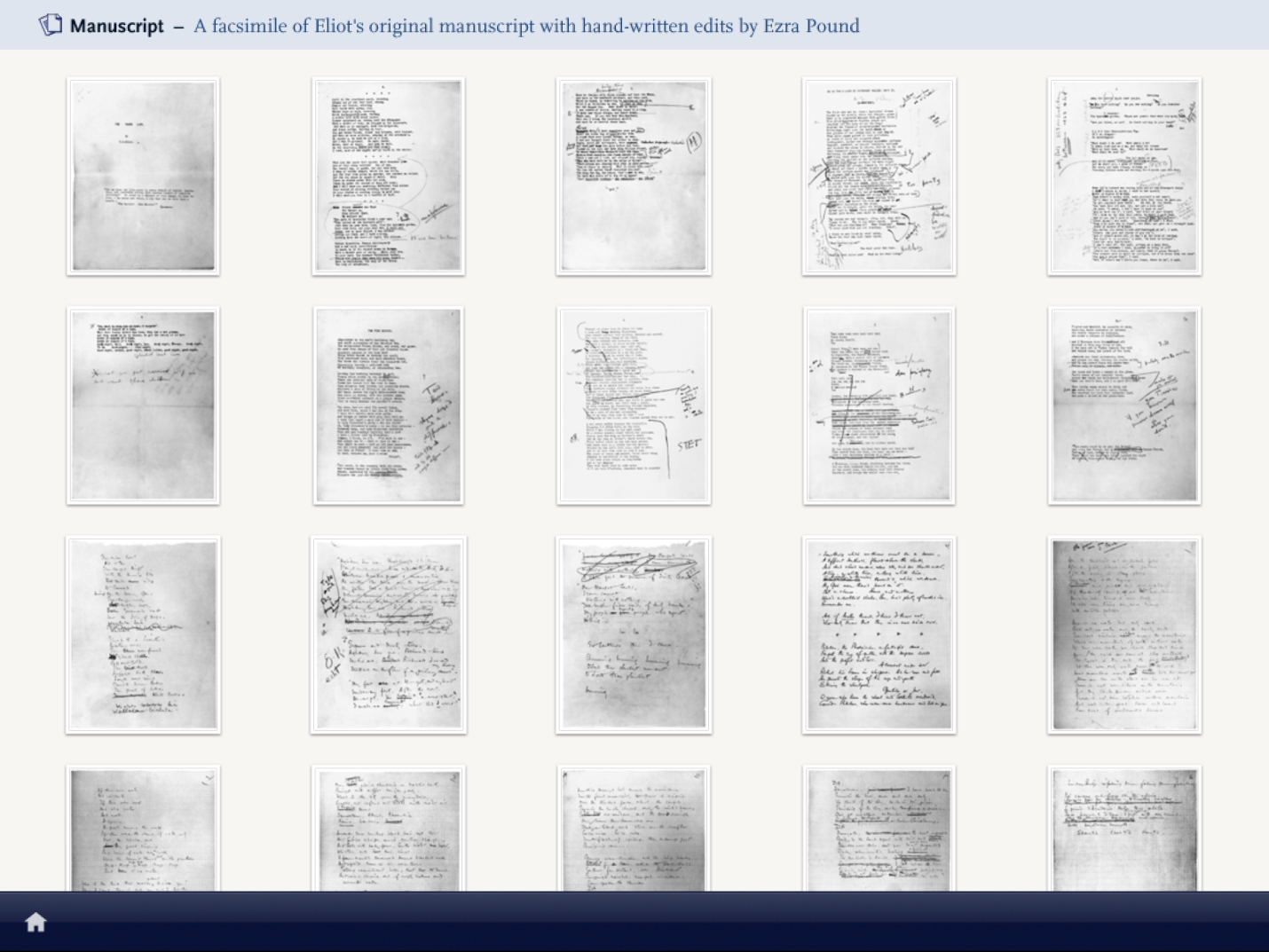

Typical of the iPad, The Waste Land as an “app” presents the reader (or viewer) with multiple ways to experience the poem in a variety of formats. In fact, the first screen the reader encounters in the The Waste Land app - the index screen - immediately offers a choice of at least four distinct versions of the work: the poem can be opened and read in what is still surely its most common format - that of a single literary work, “the fully published” 1922 text. The app also engages the poem in a theatrical fashion, offering a number of recorded “readings”, including a “specially filmed performance of the entire poem” by contemporary British actress Fiona Shaw, and, finally, the viewer has the opportunity to “click” beyond the work’s official distribution and read it as it appeared in manuscript form (see figure 1). As noted previously, the re-discovery of the manuscript in New York City in the late 1960s allowed both scholars and general readers alike to see the amount of editorial changes that had been applied to the work before its final publication. As part of the app, however, this history has been duly flattened into an instantly retrievable, albeit brief, comment on revision as an element general to all literary projects, including its best known, canonical masterpieces. The manuscript itself has been arranged for the viewer as a thumbnail grid of 20 separate images of its individual pages (see figure 2).

Figure 2 Screen Shot

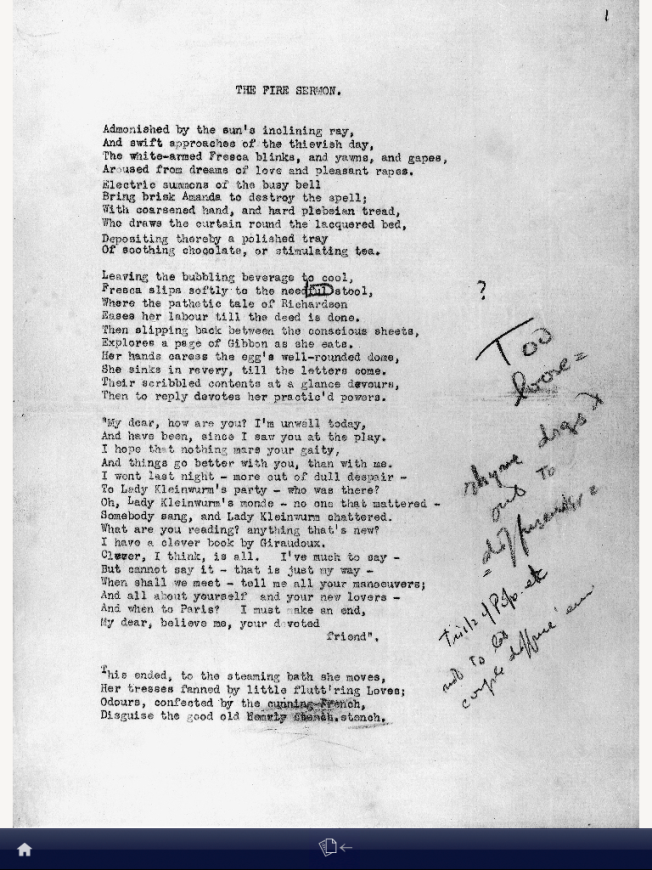

Clicking on the thumbnails will bring to full screen view a readable facsimile of each page, giving the viewer a fairly clear glimpse into the kind of editorial dialogue Eliot presumably had with Pound over the original poem. In figure 3, for example, we see an image of Eliot’s opening stanzas for section II of the poem, “The Fire Sermon.” The lines displayed are especially interesting, historically speaking, since they comprise whole sections of the original poem that Pound convinced Eliot to discard completely. It seems that the first completed draft of the work began with a caustic, somewhat vulgar description of the character “Fresca’s” morning ritual, inclusive of breakfast, choices in reading material and a few details about her washroom habits all rendered in heroic couplets in a kind of parody of Pope’s satiric verse forms one and a half centuries earlier. Pound’s critical points appear handwritten in the right margin with a few corrections penciled in over the typescript. “Fresca,” with her banal sense of self-entitlement, lack of interest or even awareness concerning the world beyond the tea and chocolates that magically appear each morning adjacent to her curtained bed, appears to have been air-lifted straight from Prufrock’s social environment. She could easily be one of “women” in the room Prufrock subtly admonishes, who “come and go / talking of Michaelangelo.” “Too loose,” Pound decides, indicating, one presumes, that the couplets are not as rigorously constructed as they should be. Nor does he seem particularly impressed with Eliot’s overall appropriation of Pope given the new poem’s themes and statements on culture.

Figure 3 Screen Shot of Original MS

Again, the literary and historical value of this dialogue even today remains quite high. What’s interesting to note, however, with respect to the digital presentation of this material as part of iPad app is how easily this part of the poem’s history can be absorbed and neutralized by the final product being highlighted as the app’s central document. Placed in the context of additional supporting material, along with recorded readings, dramatized performances and even a collection of video interviews with contemporary critics and Eliot “specialists” from various academies, the manuscript takes on a kind of pre-determined foundational role within a larger, fairly linear history of cultural evolution. In this way, the app quite effectively invokes or builds a singular narrative on the poem’s development, encouraging the reader to engage with it less as an aggregate of multiple cultural influences, dialogues and individual efforts and more as a sequential set of events leading to a final, singular product of everlasting value.

Part of the way the app achieves this effect is through its careful editorial and archiving methods, bringing together, while sifting through, a vast collection of documents and ongoing projects about Eliot and this poem. In a manner generally consistent with a long tradition of literary assessment, beginning, perhaps, with the early Christian church’s own efforts in the 4th century to construct an official “New Testament,” any attempt to collect and distribute new versions of Eliot’s work begins by determining exactly what is to be considered culturally legitimate and what is to remain “apocryphal” - that is, not worthy of supporting the current canon of Eliot scholarship. The Waste Land app certainly proves itself to be up to the task, building from multiple sources a fairly consistent and uniform narrative. The range of critical perspectives has been carefully selected and placed in an obvious effort to combine viewpoints from multiple disciplines, re-emphasizing Eliot’s cultural relevance across eras and practices. From the menu we begin with direct access to the voice and opinion of one of British writing’s most current literary authorities: Seamus Heaney; Faber and Faber, Eliot’s own publishing house, is represented by Paul Keegan; the continued academic importance of both the poet’s and poem’s legacy in Anglo-American writing is supported via interviews with two top Eliot experts, literary critics Craig Raine and Jim McCue. And any doubt of Eliot’s significance within more popular streams of modern culture is addressed through the personal contributions of hard core punk performer Frank Turner, who immediately confirms his cultural and physical loyalty to the poet by displaying for the camera The Waste Land’s epigraph tattooed in the original Greek on the underside of his wrist and forearm.

Perhaps the most significant format-related feature of the app actively promoting the poem as a statement of cultural coherence remains Touch Press’s notable removal of Eliot’s annotations from the original text to be reconfigured as a separate document available for study alongside or parallel to the poem itself. Recalling Eliot’s own personal doubt over the literary value of these additions, their excise within the app may in some way conform to the poet’s original conception of the work’s appearance and distribution. Navigating through the app, viewers are first offered the poem as a single, continuous text, its only editorial breaks visible in the form of its sub-titled sections and line numbering set off on the left margin (see figure 3). To view the original annotations Eliot added for the first book edition, the viewer must exit the poem and open up the separately titled link “notes.” This document presents the poem yet again, only this time adding an extended series of editorial comments on the left margin of the screen. The viewer is able to select individual notes with a single touch of the finger, simultaneously visually linking the annotation to the relevant line or phrase in the poem itself. As noted before, Eliot’s annotations for the first full-length book edition came at the specific request of his editor, whose primary goal, it appears, was to add to the work’s overall page count. The 51 notes Eliot subsequently provided are all available in this digital format, supplemented by an even larger set of editorial comments originally produced by Brian Southam for Faber and Faber’s A Student’s Guide to the Selected Poems of T. S. Eliot (1968, 1994). Touch Press mines specifically the sixth and expanded edition of the guide, published in 1994, which appears just as detailed now as it did then. Each section of the poem carries between 20 and 50 notes, easily tripling Eliot’s own original contributions. What must, in turn, be “noted” here, however, is how the Touch Press app with its careful control over its various interactive features is able to separate each different media component, whether it be a video performance of the poem itself, a critical commentary on Eliot’s life and oeuvre or a set of carefully linked annotations, into highly distinct, self-contained viewing experiences. The overall effect is to create in the process a pronounced continuity between viewer and the various media channels he or she engages, superseding more traditional interpretations of the poem as information fragments to be analyzed both within and alongside the work. In this way, the touchscreen offers more of the type of framework that Eliot himself may have envisioned for his epic statement (or set of statements). Certainly, as I and many other critics have historically argued about Eliot’s literary aims and The Waste Land, the poem’s fragmented, information-dependent format as a print work, laden with supplementary notes, can easily be read as a critical statement against western society’s increasingly diminished sense of its own cultural unity. One cannot properly represent ideas of truth or some kind of universal significance, Eliot seems to say, unless such values are actively supported within the social context in which they are distributed. Each stanza in the poem, as an information fragment, continues to testify to the loss of such principles, reminding us more of what cannot be stated, rather than what the words themselves are able to accomplish:

…Son of man,

You cannot say, or guess, for you know only

A heap of broken images, where the sun beats,

And the dead tree gives no shelter, the cricket no relief,

And the dry stone no sound of water. (ln 20-24)

Yet in the form of an “app” the work may perhaps finally offer the reader as viewer – epiphenomenally engaged in the work via his or her fingertips – some measure of “relief.” Neither text nor program, the poem now exemplifies a significantly different relationship to information than it did in 1922 - one characterized by the contemporary viewer’s innately ambiguous relationship to programmable language in general. Viewing digital culture through the touchscreen, we find ourselves thus momentarily free as electronic consumers of Eliot’s original suspicions of the ultimate threat information supposedly presented to cultural history’s singular, continuous sense and respect of authority. Where the symbolic form of the database, whether in print or electronic mode, inherently interrogated language in terms of its capacity to index or reference reality, the iPad app of The Waste Land attempts to restore language as an epic event of high culture, in the process, re-mythologizing Eliot and his work and life into a an even grander source of cultural authority almost a full century after the poem’s original publication. What passes for scholarly discourse in the array of authoritative figures offered to the fingers and eyes of the new electronic touchscreen viewer invites us to bear witness to the very ruins of critical interrogation as an obsolete set of practices based in inferior interface technologies, not genuine philosophical critiques of culture and authority. Thus does the electronic page claim to fulfil the printed page’s innate deficits in each subsequent digital swish.

Works Cited

Eliot, T. S. The Rock. London: Faber & Faber, 1934.

_____. The Complete Poems and Plays. New York: Harcourt, Brace, 1952.

_____. “The Frontiers of Criticism.” On Poetry and Poets. 1986. London: Faber and Faber Ltd., 1956, 1957. 109-110.

Klobucar, Andrew. “The ABCs of Viewing: Material Poetics and the Literary Screen.” Text to Txting: New Media in the Classroom. Ed. Paul Budra and Clint Burnham. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2012. 284.

Lewis, Pericles. “Religion.” Kevin J. H. Dettmar and David Bradshaw, Editors. A Companion to Modernist Literature and Culture. Oxford: Blackwell, 2006. 19-28.

McCaffery, Steve. Prior to Meaning: The Protosemantic and Aesthetics. Minneapolis: Northwestern University Press, 2001.

Cite this essay

Klobucar, Andrew. "Against Information: Reading (in) the Electronic Waste Land" Electronic Book Review, 2 June 2013, https://electronicbookreview.com/publications/against-information-reading-in-the-electronic-waste-land/