Amphibia: Infrastructure of the Incomplete

A slightly different version of this work originally appeared as part of a longer article, "The Architectural History of Disappearance: Rebuilding Memory Sites in the Southern Cone," in the December 2014 issue of the Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians. I am grateful to the University of California Press for permission to reproduce portions of that work here.

In what follows, I offer up a reading of where architecture – in particular the repurposing of spaces that have operated as torture and detention centers under twentieth-century dictatorships – opens itself up to nature, provides for nature, and in a dynamic relationship with the natural world, expands upon the ways in which both human craft and nature make meaning. In the example studied here – designs for a space called Amphibia to be situated on the land of the former Chilean prison camp and torture center known as Tejas Verdes – the built environment and nature function as a collective, fluid, and hybrid space whose interaction and interdependency give way to a new ethical ecosystem that asks for a re-evaluation of how we might integrate the legacies of torture into civil society. In particular, the proposed ecosystem of this repurposed space allows for multiple shared temporalities and new forms of memory, mourning, and political engagement. As a functional memory site – a space of memory that houses work and the routine of everyday life alongside historical reflection – Amphibia actively works toward the reciprocal remediation of history and the present moment. The ecoethics that the space communicates becomes a model for how to live with the searing social consequences of the state-sponsored perversion of man’s most fundamental and inalienable right not to be tortured.The natural medium of Amphibia responds to what is most unnatural in torture and disappearance and in so doing, opens up a space that Chile might move toward, live in, and live with.

Amphibia

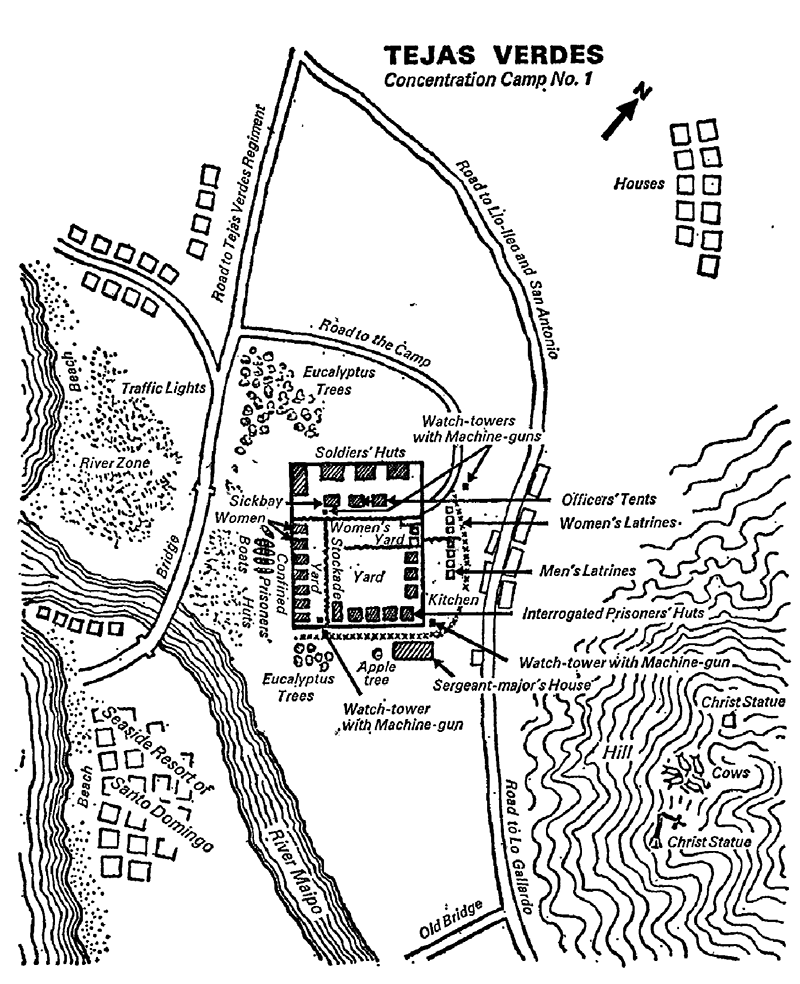

Campamento No. 2 de Prisioneros de la Escuela de Ingenieros Tejas Verdes (Prison Camp No. 2 of the Tejas Verdes Engineering School) was one of the first Chilean detention centers to be established after the coup d’état on 11 September 1973, which unseated Salvador Allende and ushered in what would become the seventeen-year Pinochet dictatorship. Tejas Verdes, about 70 miles southwest of Santiago, had been in use as an army engineering school since 1953. But at the beginning of the dictatorship, the complex was taken over by the Dirección de Inteligencia Nacional (National Intelligence Service, or DINA), the secret police branch of the Pinochet government, and set up as a clandestine detention and torture center. It operated as such from 1973 to 1976, while also serving as an important on-site training center in experimental torture techniques for DINA officers. The site sits just inland from the Pacific Coast near the resort town of San Antonio and on the banks of the Río Maipo. The camp consisted of separate huts and separate yards for male and female detainees, a sergeant-major’s house, officers’ tents, soldiers’ huts, huts for prisoners who were recovering from interrogation, a sick bay, a kitchen, and latrines. The prisoners’ yards were surrounded on all sides by armed watchtowers and eucalyptus trees. To the west lay the beach and to the east, hilly fields populated by grazing cows (Figure 1).

Map of Tejas Verdes, San Antonio, Chile (from Hernán Valdés, Tejas Verdes: Diary of a Concentration Camp in Chile [London: Victor Gollancz, 1975]).

In his 1974 testimonial work Tejas Verdes: Diario de un campo de concentración en Chile (Tejas Verdes: Diary of a Concentration Camp in Chile), in which he documents his months of detention and torture at the site, Hernán Valdés notes the proximity of the beach and river, the eucalyptus trees, the apple orchard, and the woods surrounding the camp.1 Of a trip to a makeshift latrine outside, he wrote: “Beyond the small eucalyptus wood, behind a barbed-wire fence, is a maize field. The river’s thirty yards away, curving round. From this point the river-mouth can be seen in its entirety. The camp’s hidden in a dip in the river bank. The motorists crossing the bridge can’t see us over the railings.”2 The camp is hidden in the landscape, protected by the curve of the river separating it from the beach. Nature here works to hide terror from view, or rather, man takes advantage of nature to hide terror within. By all accounts, Tejas Verdes was a bucolic setting for the horrors it would host.

Map of Tejas Verdes, San Antonio, Chile (from Hernán Valdés, Tejas Verdes: Diary of a Concentration Camp in Chile [London: Victor Gollancz, 1975]).

In his 1974 testimonial work Tejas Verdes: Diario de un campo de concentración en Chile (Tejas Verdes: Diary of a Concentration Camp in Chile), in which he documents his months of detention and torture at the site, Hernán Valdés notes the proximity of the beach and river, the eucalyptus trees, the apple orchard, and the woods surrounding the camp.1 Of a trip to a makeshift latrine outside, he wrote: “Beyond the small eucalyptus wood, behind a barbed-wire fence, is a maize field. The river’s thirty yards away, curving round. From this point the river-mouth can be seen in its entirety. The camp’s hidden in a dip in the river bank. The motorists crossing the bridge can’t see us over the railings.”2 The camp is hidden in the landscape, protected by the curve of the river separating it from the beach. Nature here works to hide terror from view, or rather, man takes advantage of nature to hide terror within. By all accounts, Tejas Verdes was a bucolic setting for the horrors it would host.

Today the site sits largely abandoned, home only to three military supply hangars. The engineering school, while retaining its name, has been moved to a nearby location, leaving, according to the architects at AGC, a “wasteland” where the camp once stood. In 2012, AGC Concept Architectes, an architectural group located in France headed by José Miguel Yañez Jaramillo in collaboration with María Dolores Yañez and Pablo Hormazábal, who work under the auspices of YH Arquitectos from Santiago de Chile, submitted a proposal to Architecture for Humanity’s biannual Open Architecture Challenge “[UN]Restricted Access” to repurpose the space of Tejas Verdes.3 The competition sought proposals from “the global design and construction community to identify retired military installations in their own backyard, to collaborate with local stakeholders, and to reclaim these spaces for social, economic, and environmental good.”4 Architecture for Humanity brings together a global network of community members with architects, design professionals, and disaster specialists and provides training for communities to develop local design solutions that respond to ongoing social problems, fill educational voids, and offer disaster relief in the built environment. The group’s social platform marries collaboration, education, environmental responsibility, and architecture.5 The ideals funded and promoted by Architecture for Humanity are wholly opposed to the totalitarian ideologies promulgated by the Pinochet dictatorship that systematically organized the torture of more than thirty thousand citizens and the disappearance of at least fifteen hundred. In submitting their proposal to the Open Architecture Challenge, then, AGC sought support from a nonstate, nonprofit entity committed to rebuilding and empowering communities in the wake of disaster. The reappropriation of this site of torture in this scenario would serve a local community reclaiming for itself what it lost under the dictatorship.

The project AGC submitted, Amphibia, reenvisions the abandoned military installation of Tejas Verdes as an ecocomplex for work and leisure that both returns the space to the natural environment and to the residents of San Antonio, a fishing port suffering from recent economic decline and high unemployment (Figure 2). In designing Amphibia, its architects sought to build a hybrid transitional space that functions as a dynamic border between the urban and the biological, serves the local population as much as the environment, and provides for a place of reflection and repose as well as action and growth (Figure 3). Above all, Amphibia, from the Greek amphis [αμφις] and bios [βιος], meaning two lives, is a space of metamorphosis where multiple dualities might meet, overlap, trespass, and inform each other.6 It stands in stark contrast to the strict ideologies that defined the detention and torture center once occupying the space. AGC’s design replaces a closed space with an open space that comprises difference, flux, and mutability. In proposing this in place of the prison camp, in lieu of the wasteland the site has become, Amphibia works to dislocate the memory and ruins of Tejas Verdes from the teleological historical continuum of state terror and resituate it in the temporal register of the kairotic, a new space predicated on the instant, the indeterminate, and the open. The space of Amphibia works – per, for example, Andrew Benjamin’s logic of the incomplete in architectural practice – to instantiate the incomplete.7

AGC begins their proposal with a brief introduction to the historical significance of the Pinochet dictatorship and an overview of Tejas Verdes as part of the machine of repression. José Miguel Yañez Jaramillo, author of the proposal and lead architect on the project, ends the introduction by foregrounding the timeliness of the project:

In Chile, this critical historical period is still cause for divisions or polarization in our society. It’s a taboo subject that gave way to a period of amnesia, necessary from our point of view for a democratic transition, as time needed for reconciliation, a collective silence that would allow us to reestablish lost social ties and habits. The year 2013 will mark forty years since the beginning of this conflictive episode. We believe it is the time, the moment, for the city and its inhabitants to take back their history, to afford an urban use to this place/non-place, to rethink this complicated sector of the urban scene so as to create a strategy of renovation and model appropriation as a response of economic, urban and ecological sustainability to the demographic, energy, and environmental challenges of future decades.8

Yañez speaks here to the divisions wrought upon Chilean society during the dictatorship and to the possibility that the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (the Rettig Commission), set up by Patricio Aylwin after assuming the democratic presidency in 1990 did not go far enough to heal the deep social wounds Chile was suffering because it did not bring to trial those who committed crimes against humanity under the dictatorship. He says that the time has come for the people of San Antonio, who might represent the larger nation of Chile, to take back their history and observes that they might accomplish this by affording to the space of the camp some usefulness, some ecologically ethical purpose. Yañez proposes that the residents of the area take control of time by recuperating the space of disappearance. Turning the ruined space into a functional place, he proposes, will help them construct a new history. The proposition of usefulness here is very important. To put the place of the camp to a new use means that there will be new civic and quotidian engagement with the space, new memories constructed, and most importantly, a new future built where before there was only a past wasting away.

Amphibia comprises five zones, or polyzones, as Yañez calls them, whose borders overlap and spaces bleed into each other (Figure 4). The first is a memorial zone named INIR, from the Spanish for “initiation,” which would feature a long walkway housing three elevated pavilions from which visitors can view the natural space around them. The second is a pavilion that would house ecooffices for start-ups or small to medium businesses. The third zone of conservation and observation would give way to a suspended aerial pier that would permit the public to view the river delta from observation pavilions while camouflaged within the surrounding flora and fauna (Figure 5). The fourth zone would be dedicated to a wall dock that would host beach access in the spring and ecolodges that would host a fluvial resort in the summer (Figure 6). The fifth zone would be an open space set aside for the organic agriculture of native crops. Amphibia is largely governed by the aim to open up the natural space of the area to the public through reflection, work, observation, leisure, or farming. The space AGC has in mind is first and foremost returned to the natural world—that same natural world used to hide the terror of Tejas Verdes from public view—but then it asks the residents of San Antonio to learn about that world, to inhabit it, and to participate in its care and cultivation.

The plan of Amphibia (see Figure 4) shows the relative placement of the zones. Note that the first, the memorial zone, looks out over the largest space of the site, which is the third zone, dedicated to conservation and bird viewing. The business zone is tucked away at the back in the northeast corner and the space reserved for the river beach and ecolodges spans almost the entire length of the site and runs parallel to the highway. The most functional spaces are situated closest to the town and give way to the more remote spaces of reflection closest to the river and beyond it, the Pacific Ocean. In this arrangement, the visitors move through usefulness in order to get to a site of observation and integration into the natural world. The implicit provocation here is that the public must put the space to use and only then might they remove themselves into a period of suspense, of stillness and watchfulness. Amphibia proposes a functional memory site, one founded on the premise that new works, daily work, and the construction of new memory will prove a worthy homage to those who were tortured or disappeared within the same space.

The Kairotic Space of Memory

A functional memory site is a complicated space. It allows for remembrance at the same time it allows for new memories to be made in a space engaged with the present. Critics of Amphibia may question the integration of the second (start-ups), fourth (ecolodges and fluvial resort), and perhaps even the fifth (native crop planting) zone since they will serve as sources of revenue. One risk is that Amphibia will superimpose onto the space of Tejas Verdes a neoliberal space of consumption by propagating similar economic injustices that helped fuel the dictatorship in the first place.9 Another risk is that Amphibia depoliticize or trivialize the space of Tejas Verdes by becoming a site of so-called “trauma tourism,” a global phenomenon that combines, as Laurie Beth Clark and Leigh A. Payne work out in their essay “Trauma Tourism in Latin America,” “leisure (tourism) with horror (trauma)” in opening up spaces of historical atrocity to visitors who want to marry their free time with social responsibility.10 But Amphibia, at least in its conception, manages to avoid both traps by fostering only local and small-scale economic development in the business zones and in the design, described more fully below, of the first (memorial) and third (conservation) zones that lead visitors to a space of memory and reflection with minimal guidance.

In its planning for large swaths of open, natural space on the site of Tejas Verdes, Amphibia aligns itself with other memory sites that have turned to open nature as memorial and thus promote a kind of ecoethics, or an ethics worked out by way of the environment. Other similar sites include the six million trees that make up the Forest of the Martyrs in Israel to commemorate the Jewish life lost in the Holocaust; the memorial site of the Nazi concentration camp Bergen-Belsen, which comprises a large, open landscape of heather punctuated by birch, juniper, and pine trees, and burial mounds grown over with natural vegetation;11 and Swedish architect Jonas Dahlberg’s controversial and now defunct plan to memorialize the 2011 mass shooting on the Norwegian island of Utøya.12 These memory sites, like Amphibia, turn to the openness and indeterminacy of nature to provide space for remembrance unbound to the chronological, historical linearity proffered by the museum, the visitor’s center, the guidebook, or even signage requiring a visitor to move in only one direction through a memorial landscape. But such memory sites avoid the trap of the sublime by asking visitors, however unconsciously, to perform the difficult task of memory work while traversing these open spaces. The negotiation of these memory spaces will fall largely to the visitor, thereby handing over agency for the production of memory to the individual instead of to a state institution.

The team at AGC offers up the first polyzone of Amphibia as a natural memorial to Tejas Verdes. Yañez explains: “No vestige of the Tejas Verdes detention camp remains. There are three supply hangars that store construction materials for the army on the land. A wasteland of a place, with no activity to speak of, this condition of emptiness drove us to a ‘détournement’ of the notion of memorial, but without losing sight of the fact that it would be the center of the proposal.”13 In selecting the reappropriation of Tejas Verdes, AGC had only the bare land to work with. The space of the camp may be a historical site, but they had no standing structure through which to communicate this historicity. So the challenge that the team took on in Amphibia is one of how to construct a space to register a history, a temporality, represented only by empty space. How they conceived of the notion of memorial had to evolve even as memorialization remained at the core of their design. What they proposed, in the end, provides for a temporal register that drafts history as only one of many possible tools we might use to engage with the past and the environment as an important catalyst for the production of memory.

In their design for Amphibia as a space not explicitly or solely identified as a memory site, AGC avoided the pitfalls of memory that Nora warns us against in his work. Residents of San Antonio and the surrounding area as well as many Chileans will know the space they are visiting as the site of the Tejas Verdes prison camp. But even as they acknowledge this, and even as they take time to reflect on the atrocities the space housed, they will also be otherwise engaged with the natural space of the site. This dual engagement with historical memory and nature allows for the production of a historical consciousness grounded in living memory, not the “reconstruction, always problematic and incomplete, of what is no longer” that Nora, and Nietzsche before him, tells us renders history an instrument of forgetting.14 AGC’s design proposes providing limited informational signage at the entrances to the first memorial zone and in the elevated pabellón de vigilia or pavilion of vigil within the zone dedicated, from an aerial vantage point, to not losing sight.15 Apart from this graphic support, visitors to the Tejas Verdes site will be expected to share in the production of historical consciousness of the space they inhabit, to bring to the site their knowledge of the crimes of torture and disappearance committed under the Pinochet dictatorship, or to leave the site with the knowledge that there are histories to which they are blind. This will make for a varied collective historical consciouness, but it also returns history to the hands of the individual and valorizes personal memory in a way no stone monument can do. Part of what AGC’s design proposes is that new, active memories of engagement with the natural world be superimposed, or in some way interact with, prior memories of recent history. This does not erase the disappeared or deny them their role in a historical imaginary so much as it allows the memory of the disappeared to inhabit various temporalities; not to become sequestered as an object of history but rather to participate in the production of new memory that exceeds the boundaries of the site.

AGC’s design imagines that this first memorial polyzone, INIR, comprise three pavilions that sit alongside an elevated concourse (Figure 7). The design for these pavilions are, Yañez explains, product of his reading of Valdés’s testimonial work Tejas Verdes. He noticed in the diary a kind of framing effect in which the surrounding landscape was fully visible but remained totally inaccessible to Valdés and the other detainees. In what reads as a kind of material reparation of that limitation, AGC’s architects proposed transforming that experience of framing into an experience of contact with nature. The natural memorial they proposed is one that brings visitors into direct contact with the natural world—the same world Valdés saw but could not access—framing Tejas Verdes. Along the concourse would stand first a pabellón intramuros, an enclosed structure that would allow the visitor a glimpse of the surrounding environment but require that he depend more fully on sound to locate himself; the second pabellón de espera, or waiting pavilion, would provide a view of the hills to the east and of the river to the west; the third pabellón de vigilia, or pavilion of vigil, alludes to the watchtowers surrounding the prisoners’ yards at the camp but in this case inverts the agency of spectating and provides the visitor with a wide aerial view of the site and the enclosed nature preserve, conceived as an “open air garden-museum.”16

The memorial space AGC’s design promises in this first zone aims to frame the landscape while also allowing the visitor to become part of it in sequential stages. The visitor to Amphibia moves from being walled in (which replicates the experience of captivity suffered by the detainees of the camp, particularly if they were blindfolded and had to depend only on sound to identify where they were being held); to waiting and watching (the only explicit agency afforded the prisoners); to a space of vigil or wakefulness that here positions the viewer in full view of the open landscape. This last space might intimate the certain wakefulness or insomnia the detainee would have suffered while in the camp, but it also invokes the ethical possibility of vigil or care, charging the visitor with, as Yañez explains, not losing sight of what happened here and keeping a watchful eye over what will happen to the space in the future. This charge, proffered after the visitor is “initiated” into nature, operates in multiple temporalities; it calls for protection of the memory of past histories at the same time it asks visitors to look out for the present space and what will become of it.

This memory space circumscribed by nature is an open invitation, indeed a call, to inhabit a new kind of ethical space itself marked by a different temporal register, the kairotic. The Greeks distinguished between two measures of time: chronos, which refers to the sequential passing of time, and kairos, which points to an opportune moment, the right moment, an instant filled with significance, a moment ripe with the opportunity for learning. Kairos is a charged and critical point in time, a point of passage to the dynamic and the meaningful.17 In his essay ” ‘The Present Obfuscation’: Cowper’s Task and the Time of Climate Change,” Tobias Menely tells us that, for Walter Benjamin a kairotic measure of time would provide for the possibility of a Jetztzeit, a “now time” that would explode open a linear historical continuum and allow us to engage with “a form of memory, still time, that would make the present legible, a ‘now of recognizability.’ ”18 Menely works out a correlation between Benjamin’s conception of history and a kind of metaphoric “meteorological legibility,” in which the interruptions and interferences of the weather act out the unexpected ways that history might open up to reveal a moment outside of historical measure, a “now time” of recognition.

Amphibia offers up the possibility of a similar legibility but in the natural world more largely understood. The natural memory space that AGC’s design proposes replaces the ruins of disappearance with the space of still time—intramuros, waiting, vigilance—that opens up the kairotic possibility of recognition. So Amphibia turns the space of disappearance into a space open to the opportune, due, and right moment of recognition that might occur outside of the linear confines of historical progression. Kairos provides for this recognition, perhaps of a historical event or past injustice, perhaps of something else, but more importantly it manifests a kind of memory that renders the present legible. And perhaps the most valuable memorial to the disappeared is one that serves as a cipher for the present. As conceived by the Pinochet regime, Tejas Verdes was a space of exception that proved the dictatorship’s historical teleology; as conceived by AGC, the site of Tejas Verdes is returned to the open space of nature, which operates outside of historical time and allows the memory of the disappeared to do the same. The open spaces of Amphibia coupled with the more functional zones of work, leisure, and sustainability together make up a site that allows the memory of the disappeared to inhabit new temporal registers predicated on openness and the functioning of everyday life. This means that in Amphibia the disappeared are participants in the construction of a new, living memory instead of remaining sequestered in historical event.

While Amphibia was selected as one of 24 (of 510) projects to make it to the semifinal round, it did not, in the end, win Architecture for Humanity’s competition. The other entries also proposed the transformation of military space into some kind of civic space, foregrounded ecological sustainability, and demonstrated the need for community rehabilitation. Other projects from Latin America that made it to the semifinals include a proposal to rehabilitate the island municipality of Vieques in Puerto Rico after having been wracked by sixty years of ammunitions and amphibious trials by the US Navy; a proposal to turn derelict military barracks in downtown São Paulo in Brazil into a youth sports academy; and a proposal to turn an abandoned police building that houses a lost archive of 80 million police documents in Guatemala City into a large-scale museum and community, cultural, and educational center that will speak to the long heritage of civil conflict and respond to entrenched legacies of violence and silence in the country.19 This last, the Kikotemal’ Rik K’aslem Memorial, won second place in the category of political response in the final round of the competition. Of these proposals, however, Amphibia is the only one to aim to reintegrate into a community and render useful a space of torture, an effort distinct in architectural mandate from the rehabilitation of other spaces in that it has to make room for crimes against humanity in the very structure of the new space it provides for. It remains to be seen, however, whether AGC will garner the funding and the permissions from the city of San Antonio to turn the site of Tejas Verdes into Amphibia; today, the space remains a wasted site of dismantled evidence of state terrorism. But Amphibia, if yet unrealized, serves as both hope for the economically depressed area and as a practical, innovative, and ethical example of how to make space for crimes against humanity in lived time and how to put the memory of the disappeared to use in the present.

The Incomplete

In his essay “The Counter-Monument: Memory against Itself in Germany Today,” James E. Young writes:

It may be true that the surest engagement with memory lies in its perpetual irresolution. In fact, the best German memorial to the Fascist era and its victims may not be a single memorial at all, but simply the never to be resolved debate over which kind of memory to preserve, how to do it, in whose name, and to what end. Instead of a fixed-figure for memory, the debate itself—perpetually unresolved amid ever-changing conditions—might be enshrined.20

Young’s observation responds to the overwhelming memorial activity that took place in Germany in the 1980s and 1990s in the long aftermath of the Holocaust, but it may be usefully applied to the memory work being done today in the Southern Cone. The debates about what to do with the spaces of torture embedded in the postdictatorial landscapes of Argentina and Chile will not soon be resolved, will never respond to a single version of historical memory, and will never satisfy the various interpretations of present or future political and pedagogical needs. As long as this irresolution remains, the memory of the disappeared persists. And in this inconclusiveness the many proposals, including the one studied here, for how to preserve or reconstruct the spaces of torture in the Southern Cone serve already as textual memorial to the disappeared.

A standing memorial, however, while it might mark a site of atrocity, fulfills hermeneutic expectations of immediate legibility and abiding symbolism that a space of memory need not meet, and one could argue, should not meet. For a space of memory can be entered into, traversed, inhabited, experienced; and in this inhabitation—be it of an enclosed space or of the natural world—a visitor might glean some cognizance of what comprises a space of torture. While the architecture of such a space may vary—again, these spaces were selected for their randomness and invisibility, not their craft of building—they have in common that they work to produce a certain unheimlichkeit or foreignness in the world that makes torture a crime not only exceeding its own temporal boundaries but undoing the very structures of subjectivity that allow for trust in the world. Holocaust torture survivor Jean Améry describes this “appropriation of the world”21 when he writes: “If from the experience of torture any knowledge at all remains that goes beyond the plain nightmarish, it is that of a great amazement and a foreignness in the world that cannot be compensated by any sort of subsequent human communication… . Whoever has succumbed to torture can no longer feel at home in the world.”22 Something of this foreignness in the world, this deep irreversible estrangement, is communicated in the proposal from the team at AGC to repurpose the space of Tejas Verdes. What Amphibia in particular provides for, however, is a space that acknowledges the inherent inadequacy of human communication of which Améry speaks. In opening up the space of Tejas Verdes to a nature preserve, Amphibia asks that visitors inhabit a realm that engages other forms of communication, a space in which human communication may reveal its own inadequacy, and then put this inadequacy to use. This is a failed compensation, to be sure, but one that acknowledges the inherent failure in all memory sites: the effort to communicate what alone may be experienced.

That the proposal from AGC works to protect or put to work this foreignness in the world is part of what makes it a viable proposition for the reconstruction of spaces of torture and a fruitful case-study of the kind of contemporary thinking that goes into conceiving of such spaces. AGC attempts to translate and reform the experience of this foreignness. In more practical terms, the architects at AGC propose initiating visitors into the open memory space of Tejas Verdes by moving them through a sequence of kinesthetic experiences that aim to replicate, as aid to the production of memory, the bodily sensations a detainee might have suffered. Amphibia—and this is what makes it an exemplary proposal for how to turn a space of torture into a space of memory—here places this foreignness, in the form of memorial, at the center of its site and then opens up that space to the everyday. But its porous boundaries, along with the explicit instruction that the site be a place of metamorphosis, ask that visitors to the site, and presumably those who will work there, conceive of this foreignness not as an exception but rather as constitutive to the workings of the world. In this conception, the memory of the tortured and the disappeared are drafted as integral to life rather than excepted from it. Amphibia, if a project still not realized, makes room for the incompleteness of the human world within the openness of the natural world.

Footnotes

-

Tejas Verdes was first published in Barcelona in 1974 and then again in 1978. It was translated into English in 1975 and published in London. The work was not published in Chile until 1996. The Orion Publishing Group currently holds the rights to works published by the imprint Victor Gollancz. All attempts at tracing the copyright holder of Valdés’s Diary of a Chilean Concentration Camp were unsuccessful. This map of the Tejas Verdes prison camps is reprinted here with thanks to Orion for their assistance throughout. ↩

-

Hernán Valdés, Tejas Verdes: Diario de un campo de concentración en Chile (Santiago: LOM Ediciones, 1996), 82; Tejas Verdes: Diary of a Concentration Camp in Chile, trans. Jo Labanyi (London: Victor Gollancz, 1975), 77:“Más allá del bosquecillo de eucaliptos, tras una alambrada de púas, hay un sembrado de maíz. El río a unos treinta metros, formando un codo. Desde aquí la desembocadura es perfectamente visible. El campamento está oculto en una hondonada en la playa del río. Los automovilistas que pasan por el puente no pueden vernos debido a las barandas.” ↩

-

The full team who designed Amphibia include lead architect José Yañez from AGC Concept Architectes in Valence, France; collaborating architects María Dolores Yañez and Pablo Hormazábal from YH Arquitectos, based in Santiago; Rémy Frapa and Cesar Baille from AGC Architectes and Constanza Neira from YH Arquitectos. I am grateful to José Miguel Yañez Jaramillo, Pablo Hormazábal, and María Dolores Yañez for their generous correspondence about the planning and design of Amphibia, and to AGC Concept Architectes for their permission to reprint images from the project. ↩

-

A full description of the open call can be found at http://openarchitecturenetwork.org/competitions/challenge/2011. There were 510 design teams from 71 countries registering for this challenge to transform abandoned, closed, and decommissioned military sites into usable and unrestricted space. The judging criteria used by the interdisciplinary jury of 33 experts in reappropriating military space considered community impact, economic viability, ecological footprint, contextual appropriateness, and general design quality. ↩

-

Further information about Architecture for Humanity and the projects they foster can be accessed at http://architectureforhumanity.org. ↩

-

José Yañez, “Amphibia,” 2. A web version of the proposal can be accessed at http://openarchitecturenetwork.org/node/12316. ↩

-

Andrew Benjamin, Architectural Philosophy (London: Athlone Press, 2000), 200. ↩

-

Yañez, “Amphibia,” 1: “En Chile este periodo histórico crítico aun es motivo de divisiones o polarización en la sociedad, es un tema tabú, que ha dado paso a un episodio de amnesia, necesaria desde nuestro punto de vista a la transición democrática, como un tiempo requerido para una reconciliación, un silencio colectivo para restablecer los vínculos y hábitos sociales perdidos. En 2013 se cumplirán 40 años del inicio de este episodio conflictivo, creemos que es el tiempo, el momento, que la ciudad y sus habitantes, se apropien de su historia, de darle un destino urbano a este lugar-no lugar, repensar este sector complejo de la trama urbana de modo crear una estrategia de renovación y apropiación modelo (ejemplar) como una respuesta de sustentabilidad económica, urbana y ecológica a los desafíos demográficos, energéticos y medio ambientales de la décadas futuras.” ↩

-

See Draper, Afterlives of Confinement, for a discussion of the consequences of neoliberalism in the reconstruction and marketing of former prison spaces. ↩

-

Laurie Beth Clark and Leigh A. Payne, “Trauma Tourism in Latin America,” in Accounting for Violence: Marketing Memory in Latin America, ed. Robert Alegre (Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press, 2011), 100. See also Jay Winter, “Sites of Memory,” in Memory: Histories, Theories, Debates, ed. Susannah Radstone and Bill Schwartz (New York: Fordham University Press, 2010), 312–24. ↩

-

Jan Woudstra, “Landscape: An Expression of History,” Landscape Design 308 (2002), 46–49. ↩

-

Dahlberg’s plan to cut a “memory wound” into the Sørbråten peninsula won the Norwegian government’s 2014 international competition for a memorial site. But the plan was cancelled in June 2017 amid much local controversy, namely that nature should not be made to also suffer the very violence it aims to commemorate. See Sarah Cascone, “Norway Officially Cancels a Controversial Memorial to Victims of its 2011 Terror Attack,” artnet.com, June 23, 2017, accessed 8 August 2018, https://news.artnet.com/art-world/norway-jonas-dahlberg-memorial-1004282 and Peter Schjeldahl, “Did a Cancelled Memorial to Norway’s Utøya Massacre Go Too Far?,” New Yorker, July 25, 2017, accessed August 8, 2018, https://www.newyorker.com/culture/cultural-comment/did-a-cancelled-memorial-to-norways-utoya-massacre-go-too-far. Dahlberg’s proposal for the memorial site can be accessed at http://minnesteder.no/Jonas_Dahlberg_-_Entry.pdf. ↩

-

Yañez, “Amphibia,” 3: “Actualmente no existe ningún vestigio del campo de detención Tejas Verdes, en la parcela existen 3 hangares de almacenamiento de material de construcción perteneciente al ejercito, un sitio eriazo o baldío, sin mayor actividad, esta condición de vacío nos condujo a un ‘détournement’ de la noción de memorial, sin perder de vista que será el centro de la propuesta.” ↩

-

Nora, “Between Memory and History,” 8. ↩

-

José Yañez, Pablo Hormazábal, and Dolores Yañez, email to author, 8 July 2013. ↩

-

Yañez, “Amphibia,” 3. ↩

-

Kairos is also related etymologically to “death,” “ruin,” “to destroy,” “to kill,” and, interestingly, “to care for.” Homer used it to mean “mortal,” but in the later works of Aeschylus, it begins to take on the meaning of opportunity. See Phillip Sipiora, “Introduction: The Ancient Concept of Kairos,” in Rhetoric**and Kairos: Essays in History, Theory, and Praxis, ed. Phillip Sipiora and James S. Baumlin (Albany, N.Y.: SUNY Press, 2002), 5. ↩

-

Tobias Menely, ” ‘The Present Obfuscation’: Cowper’s Task and the Time of Climate Change,” PMLA 127, no. 3 (2012), 489. ↩

-

See http://architectureforhumanity.org/blog/07-9-2012/unrestricted-semifinalists for full profiles of the semifinalists’ projects. ↩

-

Young, “The Counter-Monument,” 270. ↩

-

In her landmark work on torture, Elaine Scarry describes the “appropriation of the world” as the drafting by the torturer of everyday routines and objects as weapons against the torture victim. I use the term here also to describe the resultant separation from the world itself—a move constitutive to torture–that this process provides for. See Elaine Scarry, The Body in Pain: The Making and Unmaking of the World (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1985), 38–45. ↩

-

Jean Améry, At the Mind’s Limits: Contemplations by a Survivor on Auschwitz and Its Realities (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1980), 39–40. ↩

Cite this article

Bishop, Karen Elizabeth. "Amphibia: Infrastructure of the Incomplete" Electronic Book Review, 1 December 2019, https://doi.org/10.7273/bnxm-qt94