Delirium, Disruption and Death: On Stéphane Vanderhaeghe’s Charøgnards (Quidam éditeur, 2015).

Whilst reading Stéphane Vanderhaeghe’s dystopian fiction and touching on Bernard Stiegler's Age of Disruption, Greg Hainge explores the world that now reads us via a universal digitisation.

The key to understanding (or not understanding) Stéphane Vanderhaeghe’s Charøgnards can perhaps be found in the author’s long treatise on Robert Coover. From this text we understand that the multivalent realm of literature does not always proffer understanding, that it can afford us not so much a place to orient ourselves but, rather, to lose ourselves. Referring to Coover, indeed, Vanderhaeghe writes,

It might be that each text, each in its own singular way, has been repeating – rehashing and rehearsing – the initial, suicidal gesture opening [Coover’s] “Beginnings”: In order to get started, he went to live alone on an island and shot himself. (40) Perhaps there is, you muse, and has always been, in each form of writing, a propensity to self-cancellation or sabotage, to a suicide of sorts, as famously exemplified in and by the very beginning of the novel as a genre in the knight of La Mancha’s own suicidal assaults upon gigantic windmills, for instance, or in the parodic drive of Cervantes’ writing against the romances within the (extended) bounds of which, however, it keeps moving about… (Vanderhaeghe 2013: 430)

As he makes clear at the very start of this text, however, what is at play here is not (always) a literal suicide. Rather, we are here witness to a specifically literary operation that consists in enfolding or enframing the world in such a way as to undermine the self-assured metaphysical certainty of reality when this is viewed from the unitary perspective of individual subjectivity:

A multivalent text can carry out its basic duplicity only if it subverts the opposition between true and false, if it fails to attribute quotations (even when seeking to discredit them) to explicit authorities, if it flouts all respect for origin, paternity, propriety, if it destroys the voice which could give the text its (“organic”) unity, in short, if it coldly and fraudulently abolishes quotation marks which must, as we say, in all honesty enclose a quotation and juridically distribute the ownership of the sentences to their respective proprietors, like subdivisions of a field. For multivalence (contradicted by irony) is a transgression of ownership. The wall of voices must be passed through to reach the writing… (Vanderhaeghe 2013: 19-20)

To put this another way, Barthes was perhaps only half right when he talked of the death of the author, for what he was in fact talking about was the suicide of the author, an act which leaves behind a corpus, carrion (charogne) resurrected by the scavengers (charognards) that feed upon it. My choice of words here is of course deliberate, referencing as they do the title and recurrent thematic content of Vanderhaeghe’s first published novel, Charøgnards. My suggestion, lest it need be made explicit, is that Vanderhaeghe’s text turns its gaze back on us, places us in the quasi-pathological realm of the protagonist narrator, leaves us unable, like him, to distinguish fact from fiction or, rather, external events from internal imaginings – or, as we shall see, internal agency from external influence.

A truly multivalent text is one in relation to which there can, in truth, be no such thing as a spoiler because of the profound undecidability that it harbours at its core. Nonetheless, even though what is to come does not amount to revealing the identity of the murderer – or, at least, not all of them – it is only fair to warn you, dear reader, that what is to come may be considered by some to constitute a spoiler insofar as I will be obliged, in order to proffer a commentary, to regurgitate the corpus under examination and undoubtedly, in so doing, to cast it in my own image, all the while recognising the insufficiency, futility and irony (or, perhaps, hypocrisy) of doing so.

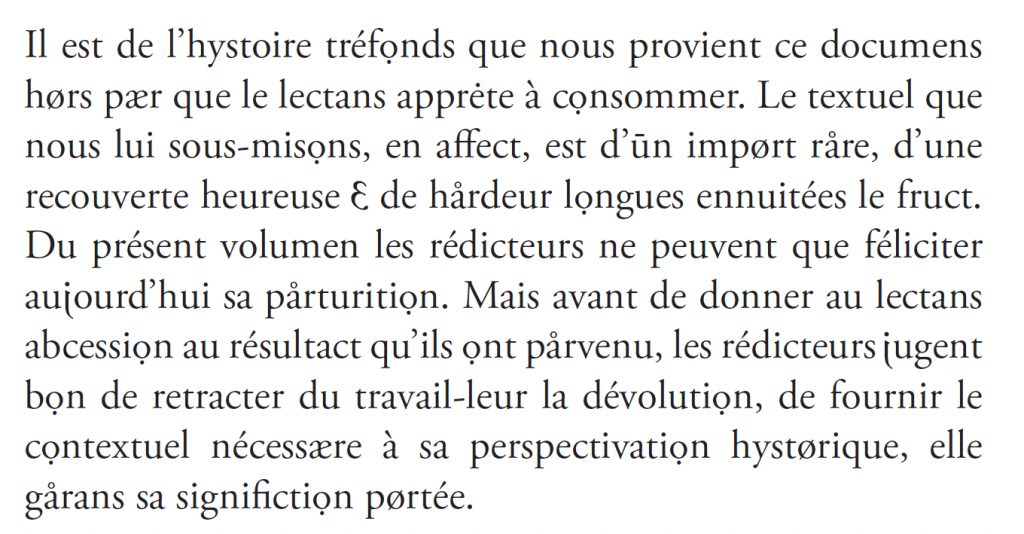

The book begins with a prologue (“Ouvertissemens”) written in a language more or less understandable to a French speaker yet rendered strange by the introduction of non-standard forms, spellings, word-endings and syntax. There are, as many critics have noted, some important precursors to what we find here: Anthony Burgess’s A Clockwork Orange with its Russian-influenced argot Nadsat being perhaps the most famous, but Russell Hoban’s Riddley Walker being perhaps a more apposite point of reference because of the way that multiple medieval and folk references are folded into this novel’s hybrid linguistic forms. Like Burgess’s and Hoban’s works, the conceit at play here is the evocation of a future world whose linguistic forms have evolved to such an extent that they remain recognisable yet appear alien to us at the same time. More than this, however, this prologue purports to be the editorial preface to an edition of a found manuscript, a journal, to be precise, that is published in the interests of trying to arrive at a better understanding of the strange ways, belief and systems of humankind. Thus the text opens as follows:

As may be apparent even to those without an intimate knowledge of French, the language we are presented with here seems to harken back to Old French forms and to reintroduce into the language a profusion of diacritics (although not necessarily the same ones) that were replaced by new spellings as Old French evolved to Middle French. At the same time, however, there are linguistic forms that are entirely new and without allusory precedent, such as the reversed letter “j”, or the hybrid, scrambled forms of words such as “abcession”, which, in its context, we read as equivalent to “accès” [access] but whose etymology seems rather to confuse “accession” and “abcès” [abcess]. The overall impression we gain as we read this preface is then one of a hybrid tongue produced out of the average values of the myriad forms of a language that has evolved across time and that is here apprehended in its entirety via a computational or algorithmic operation devoid of the understanding that would be provided by a consideration of context. This is to say that meaning is here produced only as an after-effect of an analytic procedure that produces and places syntactic units in an operationally defined sequence, all the while encoding into this new language as integral elements the glitches produced by corrupt data or transmission errors.

To take but a couple of examples, we are often faced with word forms that (as was the case with “abcession”) blend together two distinct yet proximate words or that result from the replacement of one term with a proximate one (again, in terms of the letters that it contains), such that we find, for instance, in the place of the word découvrir [to discover], that is called for by the context, the word “recouvrir” to cover over, which, when read as such, makes no sense. Similarly, the preface talks of the journal’s “contenu détonnant”, a phrase we understand to refer to the journal’s “surprising contents”, even though the word for surprising (étonnant) is here replaced by the present participle of the verb détonner [to sing out of tune / to be out of place] – an easy mistake to make, perhaps, since adjectives in French can be prefaced by the preposition de when this introduces an epithet in an indirect construction, as in the phrase quelque chose d’étonnant [something surprising].

In cases such as this last example in particular, the suggestion seems to be that the language we are presented with is produced out of an image-based analysis of the physical forms of words that attributes an average value to similar forms, as if language had, at some point in the distant future, needed to be entirely reconstructed solely from the image files of Project Gutenberg. The machinic tone imputed to the language here derives not only from an imaginary extrapolation of how such a language would come to be in the first place, however, but also from the commentary provided that revels in the unique opportunity afforded by the discovery of this “homomanuscrit” [humanuscript] to gain unprecedented insight into the history, culture and emotions of a race now long extinct. The authors of the preface, indeed, feel obliged to explain for their readers precisely what the strange text they are about to read actually is, this so-called “journal” that they describe as being distinctly of its time, an attempt to preserve something of an identity, a language, a culture perceived to be under attack and in danger of disappearing, a textual form that is at one and the same time then the last stand in a battle already lost and an attempted act of memorialisation. As alien as some of the concepts that are found in the journal appear to be for the authors of the preface – in particular the odd way that aspects of existence are segmented into different kinds of aggregates, such as “days” or “villages” – they nonetheless find here some kindship and suggest that much of what is related herein can but resonate strongly with their own most ancient mythologies (13). In saying this, Vanderhaeghe seems to inscribe his novel in a lineage that connects it to Houellebecq’s La Possibilité d’une île, in which different sections of the text correspond to different times, the present and far flung post-apocalyptic futures recounted by the future clones of the originary protagonist. Believing in the conceit presented to us in the preface, we thus enter into the main narrative of the found journal manuscript with a terrible sense of foreboding, wondering what kind of event could have triggered such a future, could have led to the wholesale destruction of language and, indeed, of humankind as we know it now.

Given the future we believe we are heading towards, the sense of menace that pervades the novel and that appears, indeed, to have prompted our narrator to put pen to paper in the first place strikes us as somewhat baffling, for it is elicited by nothing other than birds. Driving home with his wife C. and their child after a walk in the forest, the narrator sees ahead of him a small group of birds feeding on the carcass of roadkill. One of the birds seems to look straight at him as he keeps his course, heading straight for them. As he approaches, however, the birds calmly fly away, only to return to their feast as soon as the car has passed. There is in this opening scene nothing particularly horrific, nothing to indicate the catastrophe we believe to be coming, yet the same cannot be said of the impression this scene leaves on our narrator, for whom this scene is premonitory and takes on a huge and oppressive dimension that will only grow as time moves on:

“What should I make of what just happened?”, I ask myself.

No sooner had the question formed in my head than there seemed to be more of them on the road. Perhaps though this was just because of the speed I was travelling, that blurred the quickly fading reflection in my rearview mirror. A slight bump reframed the view and I saw a blind light tear through the heavy sky before being swallowed up by the country road tailing behind me. Amputated, compacted and stretched like this, I felt the ghostly mass of the sky weigh heavy on this scene. Scavengers: straight away the thought crosses my mind in silence.

It is with this word, at this very moment that clouds of them begin to churn in the wash of the sky. Then nothing.

The shock makes me swerve.

It’s nothing, I say. (26)

There is already here some intimation that the crisis we know is coming is one that is situated within rather than outside of the narrator. Read retrospectively, indeed, his final words here are rife with ambiguity, for we cannot tell if this is a reassurance to himself that there is in fact nothing sinister going on, or, rather, to his wife C. in order to shut down a conversation by assuring her he is OK. As we progress deeper into the narrative, this ambiguity only grows, the narrator himself questioning more and more the reality of what he sees around him: “a feeling of suffocation. And yet this stubborn sense that none of this is real” (75).

Commentaries such as this, that cast into doubt the veracity of the account we are reading, increase as the journal progresses and serve a number of different functions in the text. On a diegetic level, of course, they map the narrator’s gradual descent into the paranoid interiority of a psychological space increasingly distanced from the concrete ambient reality around him. This seems, at times, to be a self-imposed exile, the only possible response to a reality perceived as a constant threat or, perhaps, a necessary mechanism to carry on living in the face of a reality that, for many reasons, the protagonist must attempt to cover over through a deliberate act of fabulation. The narrator, indeed, lays out his strategy explicitly, describing it as a catharsis, a necessary form of therapy in the face of the breakdown of his marriage:

My strategy is simple: to bury the fragments of the official version of events that came back to me under their unofficial doubles that, I have no choice, I will end up believing to be true. (75)

Shortly afterwards, however, the spectre of a different motivation rears its head:

You took our child with you. I find a note on the kitchen table when I get home explaining everything: that you can’t do this any longer, that you no longer feel safe, that you love me or rather did love me, but this just can’t go on, a stable environment for our son, away from the shouting, the fear. You’ll call me when you arrive. You stuffed a few bags into the boot of the car and then left.

This version of events works well for me.

Except for the fact that the car is parked in the driveway. (76)

This avowal by the narrator of a deliberate strategy of fabulation enacted as a defence against a reality perceived to be unbearable in its raw form – and thus in effect of his own untrustworthiness as a narrator – also doubles down on the text’s artifice by bringing into the fray a metaliterary dimension that is explicitly signalled in the text by a direct intertextual reference to Louis-Ferdinand Céline. This very same strategy, indeed, is one that we find throughout Céline’s career, from his early medical thesis on Semmelweis, through his first, most famous novels Voyage au bout de la nuit [Journey to the End of the Night] and Mort à credit [Death on the Instalment Plan], his anti-Semitic pamphlets written during the period of World War II and right up to his final trilogy that gave a fantastical, quasi-hallucinatory account of his time in exile travelling through Denmark and Germany in the post-war period. Céline himself gave subtle clues as to the transposition of reality into a fictional realm in operation in his novels via changes to dates or the spelling of proper nouns, changes that were sometimes very subtle (such as the reversal found in the title of his medical thesis where Ignaz Philipp Semmelweis becomes Philippe-Ignace Semmelweis) and sometimes not so subtle (such as his vituperative rants against other writers he names “Tartre” or “le grand Sâr blablateux” [Sartre], “Brottin le maniaque gâcheur” [Breton] or “le gastrique Larengon” [Aragon], to name but a few). This very same technique is used by Vanderhaeghe at one point in his text, as he provides a dictionary definition of the word CHAROGNARD, going on to quote, as examples of usage, extracts from Céline’s first two novels that are here attributed to “Féline, Voyage au bout de l’ennui, 1932” [literally Journey to the End of Boredom, better translated, in order to transmit something of the homophonic character of the French, as Journey to the end of the Slight] and “Féline, Tort à credit, 1936” [Wrong on the Instalment Plan or perhaps, as before, Mess on the Instalment Plan].

Other intertextual references plunge us into a similarly metareferential and thus avowedly non-realistic realm. The most obvious of these is the homage to Hitchcock’s The Birds that the novel seems to be – even if Vanderhaeghe claims that the similarity only occurred to him once he had started writing (Vanderhaeghe and Ted 2015). Another vital clue to understanding the novel comes also, however, in the intertextual nod to Stephen King’s The Shining, and/or Stanley Kubrick’s famous film adaptation of this book. Like Jack Torrance – the main protagonist of King’s book played by Jack Nicholson in Kubrick’s adaptation – the narrator of Vanderhaeghe’s text suffers from writer’s block, a condition that brings about a quasi-pathological regression into one’s self experienced as an inability to externalise one’s thoughts. In the case of the leads of both Vanderhaeghe’s and King’s works, this is signalled by the isolated setting in which the characters find themselves – and that serves as a literal embodiment and spatialisation of the inner mental state of these characters – but also by the concrete, pathological forms of the texts that they produce when able to write. I refer, of course, to the chilling moment in Kubrick’s film when we see – along with his wife, Wendy – that the piles of typewritten text that Jack has been working on for weeks contain nothing but the obsessively repeated mantra “all work and no play makes Jack a dull boy”. Similarly, in Vanderhaeghe’s book the plastic form of words on the page takes on an increasingly significant role, morphing as it does from the kind of concrete poetry stylistics of Apollinaire (such as when the word “ver” [worm] is written repeatedly in a vertical aspect to form a squiggle across the page) into a physical manifestation of the narrator’s gradual loss of a hold on reality:

None of this happened.

None of this happened.

None of this happened.

None of this happened.

None of this

None of

None (113)In a remarkably inventive use of typesetting, this breakdown in Vanderhaeghe’s novel progresses to such a point that the entire text seems to break up before our eyes at the same time as the pages gradually darken until we are left with nothing but (not a blank page as is the case for someone suffering from writer’s block) an entirely black page. Before this point, however, the concrete techniques that seem at first playful gradually transform into a plastic treatment of letters on the page that uses directionality, mirroring and reversal as a means to push at the limits of legibility, requiring of us, the readers, an enormous effort to make these letters cohere, to make the text relinquish its sense, this making of us the mirror image of the narrator. This plastic treatment of text that renders language unfamiliar, combined with the introduction of strange hybrid forms – such as “putréfictionne” (238) [putrefiction] – recall the book’s preface which, in retrospect, can be read as the text produced after the narrator’s mental collapse is complete, once he is not only no longer able to refer to himself in the first person but only the second person, but unable even to recognise himself as being of the same species as what he has become.

To see the book’s preface in this light is, perhaps, to rob it of its power as a fictional device – and there will undoubtedly be readers who prefer to read it far more literally. To read its science fiction hybrid linguistic forms produced out of an algorithmic logic as, rather, the pathological emanations of an unsound mind that has entirely lost its grip on reason allows us, however, to read Vanderhaeghe’s novel not only for its considerable literary qualities but also its powerful commentary on the contemporary moment in which we find ourselves. Written in bursts of activity between 2011-2015, Vanderhaeghe’s text is produced at a time when the world as we know it now was in full effect, which is to say a world in which the linguistically mediated nature of our perception of reality that is explicitly addressed in his text is overlaid with another layer of computational mediation that interposes itself between us as individuals and that which lays beyond us.

For a thinker such as Bernard Stiegler, the very nature of this new form of mediation that derives from the universalisation of the digitisation of the information technologies through which the world increasingly comes to us has occasioned a fundamental shift away from Reason to madness, a universal loss of reason or derationalisation. For Stiegler, it is primarily the speed of these technologies that has occasioned this shift, since they deploy connections across a vast network one to four million times faster than the synaptic connections of our own nervous system (Stiegler 2019: 7). As a result, in this age of disruption, outstripped by the speed of these technologies, the faculty of Reason via which the individual determines their own place in the network of civilisation through the subject’s own volition and desires is effectively outsourced to the computerised processes determined by complex algorithms. He writes:

The automatic power of reticulated disintegration extends across the face of the earth through a process that has recently become known as disruption. Digital reticulation penetrates, invades, parasitizes and ultimately destroys social relations at lightning speed, and, in so doing, neutralizes and annihilates them from within, by outstripping, overtaking and engulfing them. Systemically exploiting the network effect, this automatic nihilism sterilizes and destroys local culture and social life like a neutron bomb: what it dis-integrates, it exploits, not only local equipment, infrastructure and heritage, abstracted from their socio-political regions and enlisted into the business models of the Big Four, but also psychosocial energies—both of individuals and of groups—which, however, are thereby depleted. (Stiegler 2019: 7)

Transformed into data providers, these entities (both the individuals and groups that the so-called “social” networks take apart and reconstitute according to new protocols of association) are stripped of their individuality: their own data, which constitute what we might call (drawing on Husserl’s phenomenology of temporality) their retentions, are then what allow them to be dispossessed of their own protentions – which is to say their own desires, expectations, volition, will, etc. (Stiegler 2019p: 7) By thus outsourcing individual choice, agency and, consequently, the very capacity for Reason, what we are witnessing in this age of disruption occasioned by the advent of computational capitalism is, for Stiegler, precisely what Horkheimer and Adorno foresaw fifty years ago, namely the emergence of a new form of barbarism that signals, in effect, the end of civilisation.

It would be easy to mistake Stiegler’s vision of an entire civilisation stripped of its agential capacity and thus driven to madness by the rise of machines for a post-apocalyptic, science fiction speculation, but this is not the case and Stiegler’s book is intended as a diagnosis of our contemporary condition. Similarly, to return to Vanderhaeghe’s Charøgnards, while it is tempting to read the book’s prologue literally, as a science fiction anthropological exegesis from the future, the gradual disintegration of language across the text prompts us, as I have suggested, instead to read the book’s prologue as the product of a disturbed mind no longer able to maintain a hold on reality in our own time. What is so remarkable about this prologue when read in this manner is how the very linguistic forms used, that mimic the kind of text that might be produced by an algorithmic logic using AI and deep learning networks, articulate Vanderhaeghe’s text to Stiegler’s diagnosis of our contemporary condition as one that is fundamentally pathological. When read in this way, Vanderhaeghe’s novel becomes, I would suggest, more rather than less terrifying, at the same time as it shows by example precisely why we need books like this, multivalent books that exemplify the suicide principle that Vanderhaeghe situates at the very heart of the literary enterprise. For if the novel effectively effaces its own voice in its refusal to be bound to a unitary meaning, to impose its own will and thus rob the reader of agency, then this suicide is surely preferable to the murder that the supplanting of creative agency would constitute. Ultimately, Charøgnards is perhaps, then, a cautionary tale, and it is one that we have never needed more since it appears at a point in time when we are not only seeing the computational capitalist logic analysed by Stiegler consolidate its dominance, but when early experimentation in the production of literature, painting and music via algorithms formulated by AI connected to deep learning networks is well underway.1

Greg Hainge, University of Queensland

Works Cited:

Bernard Stiegler. 2019. The Age of Disruption: Technology and Madness in Computational Capitalism, translated by Daniel Ross. Oxford: Polity Press.

Vanderhaeghe, Stéphane. 2013. Robert Coover & the Generosity of the Page. Champaign: Dalkey Archive Press.

Vanderhaeghe, Stéphane. 2015. Charøgnards. Quidam éditeur. All translations into English are my own.

Vanderhaeghe, Stéphane and Ted. 2015. “Interview de Stéphane Vanderhaeghe”. Un Dernier livre avant la fin du monde, 3 September 2015. Available online: https://www.undernierlivre.net/interview-de-stephane-vanderhaeghe/ , accessed 28 May 2019.

Footnotes

-

See, for instance, Ross Goodwin’s Fiction Generator that used AI and algorithms to produce a novel from the CIA’s Torture Report in 2014; the painting produced by art collective Obvious that used an algorithm to synthesise 150,000 portraits painted over seven centuries, Portrait of Edmond Belamy; CJ Carr and Zack Zukowski’s fake death metal band dadaBots and the increasing number of products on the market or in development seeking to produce music via purely computational means – such as Flow Machines, IMB’s Watson Beat, Google Magenta’s NSynth and Amper Music, to name but a few. ↩

Cite this article

Hainge, Greg. "Delirium, Disruption and Death: On Stéphane Vanderhaeghe’s Charøgnards (Quidam éditeur, 2015)." Electronic Book Review, 5 July 2020, https://doi.org/10.7273/vvqz-8173