Digital Ganglia and Darren Wershler’s “Nicholphilia"

This essay engages with the complex translation of materiality that occurs between Darren Wershler’s NICHOLODEON (1997) and its eventual digital incarnation as NICHOLODEONLINE (1998). Both of these works pay homage to the influential avant-garde Canadian poet, bpNichol. Beyond situating Wershler’s texts in a historical framework that moves from Nichol to the 'Pataphysics of Alfred Jarry, Sean Braune looks at select metadata “clues” that Wershler left behind for the curious-minded reader (human and machine), as well as placing Wershler’s work (and Nichol’s by extension) in the context of theories of language that move from the human to the “tower of programming languages” that are described by Rita Raley and Friedrich Kittler.

The focus of this essay will be Darren Wershler’s NICHOLODEON: a book of lowerglyphs and its living, digital manifestation as a ganglion of texts and links in its online version, NICHOLODEONLINE. Wershler creates a textual homage to the influential Canadian avant-garde poet, bpNichol, in NICHOLODEON, which is a “book” initially published as a print version in 1997 and then later in an online iteration as NICHOLODEONLINE in 1998. The materiality of each iteration differs drastically from the traditional appearance and presentation of its book version to its online manifestation. NICHOLODEONLINE is a moving and dynamic aggregate of pathways—it is a ganglion of intersecting points. NICHOLODEONLINE is more attuned to Nichol’s own poetic oeuvre because the materiality of NICHOLODEONLINE presents as ganglia (the term “ganglia” resonates in Nichol’s oeuvre as the name of a small magazine and press that he formed in 1965 with David Aylward). The Greek physician Galen uses the term ganglion to designate a complex nerve centre that appears as an intersection point or as a “consolidated structure” (217). Because of Nichol’s interest in the embodied quality of language, it is easy to extend the notion of the ganglion to designate a point of consolidation or intersection between the physiological, biological, and semantic. A meeting place appears between signifier, signified, referent, and body and such a meeting place functions like a kind of ganglion; a tightly interwoven knot of meanings in flux and becoming. The notion of a ganglion is apt for discussing a complex point or event of intersection and consolidation because a ganglion is, by necessity, liminal; it is both an interwoven knot of complex materiality and can also be a tumour that develops on or near a sinew or a tendon. A ganglion is multifaceted in that it is an informational hub in the body that allows for the transition of electrical information along synapses, but it can also denote a swelling or a tumour on or near a tendon. For this reason, I think of NICHOLODEONLINE as a complicated ganglion that is composed of the consolidation of print and electronic media—it is a tightly knotted online network that builds on and is linked to its print iteration. The online version can be navigated like a ganglion in that the reader or the viewer functions very much like a synapse who travels along a nerve.

From an experiential perspective, both iterations of Wershler’s text—or is it “texts?”—offer drastically different engagements with textuality, language, and materiality. Both NICHOLODEON and NICHOLODEONLINE wear their anxieties of influence on their sleeves, so to speak, and situate this Wershler-created ganglion as an archaeological or a genealogical site. NICHOLODEONLINE is akin to an archaeological locale that requires nonlinear reading practices: the text does not progress in a linear fashion—as it does in the print version for example—but rather proceeds along a nonlinear process of clicks as a reader or viewer experiences the text or texts through the various pathways of the textual-digital-ganglion. It is a ganglion of forking paths. The content is repeated between the print and the online versions, but the experiential aspect of moving through the text is drastically different. This is also the case with any digital text or poem; however, what is interesting about Wershler’s homage to Nichol is its dual manifestation as both print and digital in versions that can be read or experienced singularly or in whatever order the reader or surfer chooses. NICHOLODEONLINE and NICHOLODEON manifest the tense relationship between print and the digital and comment as well on the larger anxiety of influence that links Wershler’s early poetic experiments to Nichol’s own artistic and poetic practice.

It is for these reasons that NICHOLODEONLINE and NICHOLODEON are locked—singularly and together—in a complicated interplay of adaptation and remediation. Perhaps these concepts create their own ganglion of relations to Wershler’s project. As I mentioned earlier, NICHOLODEONLINE is an electronic literary adaptation or reproduction of NICHOLODEON that also engages in processes of remediation because of its transition from print to digital. Jay David Bolter and Richard Grusin point out that remediation is the “representation of one medium in another” (45). Instances of remediation also accompany some degree of loss; Aaron Mauro, for example, reads Jonathan Safran Foer’s Tree of Codes (2010) through the notion of loss—specifically, the various forms of loss that are engendered by Foer’s erasure experiment that cuts through Bruno Schulz’s The Street of Crocodiles (1934). Any intermedial text is subject to various degrees and types of loss. NICHOLODEONLINE performs its own remediated loss in relation to NICHOLODEON, but does so in a unique manner that emphasizes the thematic import of a Nicholian ganglion.

The print version of NICHOLODEON can be entered through a reading practice of traditional linearity; i.e., the reader has the option of beginning on the first page and proceeding, in a linear sequence, through the text. There are several options for engaging with the work. Instead of creating a table of contents, Wershler begins the book with a “Legend” and this “Legend” acts as the central, guiding node of the print version. The “Legend” includes such topics as “appoggiaturae,” “metempsychoses,” and “nicholphilia.” Therefore, even with the print version, the reader could potentially move through the text in an experiential manner that matches the networked structure of NICHOLODEONLINE; however, the materiality of the book—and the ideological dictates of readerly habits—lead the well-trained reader to proceed like a traditional grid thinker, which is to start at the “beginning” and move through to the “end.” The “body” of the text of NICHOLODEONLINE is primarily discovered through clicking the “lowerglyphs” link. This choice makes intuitive sense because the subtitle of NICHOLODEON is “a book of lowerglyphs.” The “Legend” itself can be considered a kind of dissertation on Nichol’s oeuvre in that it is similar to a ”pataphysical walk-about Nichol’s influence on the Canadian avant-garde. The print version betrays its own death drive because it contains a section at the end called “Instructions for Disposal” in which a playful list of 26 instructions are given to destroy the book. The helpful “Surplus Explanations” section at the end of the print edition says, regarding “Instructions for Disposal”: “Go ahead. Display your casual contempt for commodity fetishism and your commitment to a general economy by destroying this book” (n.p.). Apart from engaging with NICHOLODEON in both a linear and nonlinear way, the text itself instructs a reader, if the reader so chooses, to destroy it.

NICHOLODEONLINE manifests in a manner that is reminiscent to Alfred Jarry’s spinning Clinamen machine that is found in his experimental novel, Exploits & Opinions of Dr. Faustroll, Pataphysician (written in 1898 and first published in 1911). The Clinamen machine is a spinning cylindrical device that spits paint onto the walls “in the iron hall of the Palace of Machines” (88-89). The references to the Clinamen machine in Exploits & Opinions of Dr. Faustroll, Pataphysician lead to the generalized ’pataphysical interest in the clinamen atomorum or the “atomic swerve” of Lucretius (63, II: 217-225). In any case, the digital version of NICHOLODEONLINE behaves like a kind of Jarryesque Clinamen machine because the “lowerglyphs” connect to the various links and striations of the text—these striations are like the paint-signs that the Clinamen machine sprays on walls. The print version, on the other hand, does not act like a Clinamen machine.

Admittedly, NICHOLODEONLINE lacks the full dynamism of Jarry’s ’pataphysical machine, but it does contain some degree of readerly interactivity in the production of meaning or even non-meaning. Alan Liu argues, in “The End of the End of the Book” (2009), that “the digital subordinates books, films, music, and anything else to a focus on documents (or, equivalently, files)” (505), and NICHOLODEONLINE manifests such a mode of digital absorption—it is a collection of documents, files, or better yet, links that lead to a kind of “art installation” in the digital realm where each linked page presents like the wall of a museum in cyberspace. The intermediality of NICHOLODEON is subsumed by the digital in a manner that renders the online experience of NICHOLODEONLINE one of direct consumption where the original text is transformed by its digital likeness. NICHOLODEONLINE thwarts NICHOLODEON because the ideality of the remediated text reorganizes the concrete poems of the print version and subsumes the differentiation of these images and texts under the heading of “files” or hyperlinks.

The possibility of NICHOLODEONLINE to mirror or manifest as NICHOLODEON is foiled because the reader/viewer experiences a new text in a new medium. Certainly, this is one of the hallmarks of remediation, but the experience can be somewhat jarring because it opens onto a variety of alternate pathways and remakes these pathways through newly reified forms. However, this claim does not deny that there remains an experience of familiarity or recognition when engaging with NICHOLODEONLINE—a familiarity that registers a similarity with the “original” print text. And yet there also remains an eeriness to the original text because it is already intermedial; it is a book of concrete poetry and features a variety of images and text-image combinations. On the one hand, the visual appearance of NICHOLODEON renders it intermedial, but its materiality is made explicit through the medium of print and the direct tactility of the book; NICHOLODEONLINE, on the other hand, lacks the tactile experience of a codex or a manuscript because its contours remain outside of human experience and firmly within the dimension of digital source text. The “contours” of NICHOLODEONLINE are, for this reason, primarily “read” or materially “cognized” by the computer, who functions very much like a robopoet, as the computer translates the source text, which is, in this case, the unconscious textuality of the online code, into the surface of human-based textuality. To a certain extent, this argument is similar to saying that the materiality of print is absent in the online version of NICHOLODEONLINE, but the issue becomes more complicated because of the various instances of textuality that are involved: 1) the palimpsestic dimension of the structural code (that is read by a nonhuman computer or machine), and 2) the surface appearance of an anthropocentric text (and there are, no doubt, many levels that would exist in between these two planes).

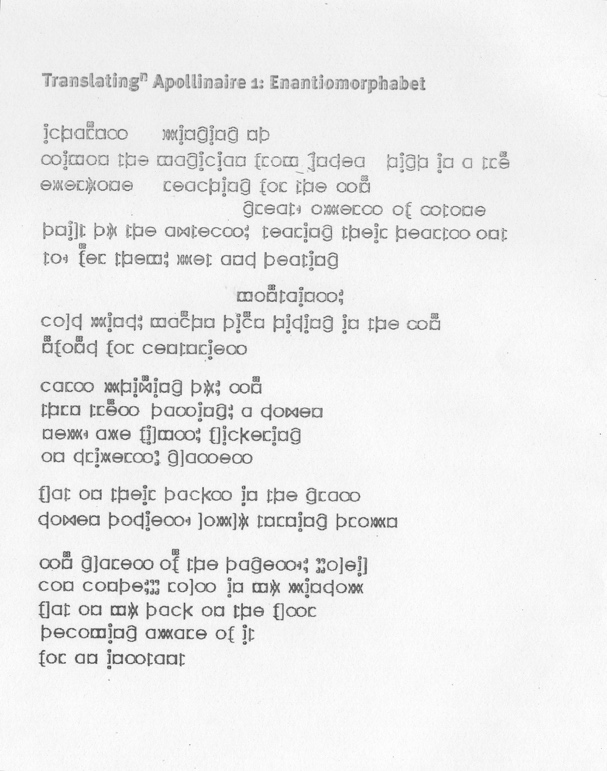

One way to conceive of this structure—which is a structure that reflects Nichol’s own conceptual and aesthetic interest in ganglia—is to read the text or the levels of the text in relation to a mirror. The print version of NICHOLODEON “begins” after several images of concrete “errata” with a homolinguistic translation that is written in the tradition of Nichol’s own series of “Translating Translating Apollinaire.” Wershler’s “Translatingn Apollinaire 1: Enantiomorphabet” is a whimsical homolinguistic translation of an Apollinaire poem through the ”pataphysical theory of enantiomorphosis.

I have written about enantiomorphosis and its importance for the Canadian avant-garde elsewhere, but here I want to draw attention to the ways in which enantiomorphosis is an act of ”pataphysical copying that creates a complicated play of mirrors and mirroring. Enantiomorphosis is a useful way of conceiving of the ganglion that emerges from the conceptual interplay of intermediality, remediation, adaptation, and versioning loss. Enantiomorphosis is itself a myth—a post-Borgesian myth—that is “discovered” by Christian Bök when he historicizes the origins of the Catoptriarchs, “a Slavonic sect of Christian Gnostics” who “advocated the Enantiomorphic Heresy, which declared that all earthly existence was but a fleeting reflection in a looking glass unveiled in the gardens of the Heavenly Father” (Crystallography 142). Enantiomorphosis is a concept proposed by the Catoptriarchs—a ”pataphysical sect that remains untouchably transcendent, but nonetheless manifest through the immanent textuality of the present. The inexistence of the Catoptriarchs bleeds into the present like a data pour that is positioned through a post-Borgesian mythography; this process operates in much the same way as a homolinguistic translation that functions on the basis of a ”pataphysical swerve or the creative productivity of a clinamen. The Canadian ”pataphysical interest in the clinamen emerges from the importance the French Oulipians and ’pataphysical writers placed on the literary or poetic concept or conceit as an image of chance that results from a constraint-based writing practice (Becker 87-88). Warren F. Motte, Jr. discusses the influence that the clinamen has had on experimental writers—he especially highlights Georges Perec—as well thinkers as disparate as Michel Serres, Harold Bloom, René Thom, and Ilya Prigogine (19-20).

How is a clinamen like a data pour though? When Liu discusses “data transcendence” in “Transcendental Data” (2004), he is referring to his conception of “data pours,” which is an idea that refers to the hyperlinked moments that can be clicked and moved through towards further text and data streams. “Data pours” are connected to other websites and content (59) and designate an unknown quantity of information because textuality extends beyond the present, surface text and manifests as a digitally transcendent palimpsest. According to Liu, data flows from transcendent sources in online media and in this way, an experience of “reading” electronic literature is, by necessity, palimpsestic.

The metadata in the source code of NICHOLODEONLINE is unique because it contains text that remains present for the computer-reader, but not for the human-reader. As N. Katherine Hayles points out in How We Think (2012), the field of machine reading is still in its infancy (71), but it is important to acknowledge that computers do, in a way, read; they just do not read in a human way. Hayles develops three modes of reading in How We Think that include the more traditional version of close reading alongside “hyper reading,” which is a mode of reading that is endemic to the contemporary digital age of informational excess, and “machine reading,” which is a kind of reading that can supplement the work of a traditional humanities scholar in order to address questions that would be infeasible for a human reader—these questions typically relate to the “reading” of massive repositories of information or large digitized corpora.

The image of the “Enantiomorphabet” pictured above is named, in the source code, on line 40 of that page, as: “Pretty landscape, the walls and ceiling lodge in the debris of mirrors as best they can.—Jacques Rigaut” (n.p.). Another double exists in the source code of NICHOLODEONLINE as demonstrated by the hidden inclusion of this quotation from the surrealist poet, Jacques Rigaut. What is unique about this hidden message or quotation in the source code is that a computer-reader would have no knowledge, awareness, or investment in the poetry of Rigaut—he is, of course, a human poet—but it remains in the source code as a message that ostensibly exists for the computer, unless a curious human poetry-reader consults the source code.

The problem with an enantiomorphic double is that it becomes an ideological knee-jerk to claim that a double is a double of an original; i.e., a copy or an exact reproduction or (re)duplication of an originary source. However, the issue with an enantiomorphic and a generalized double is that the double is its own entity—that is, it is uniquely singular—even as it exists in simultaneity with the ontological status of a “double.” What this means is that every mirror image or act of mirroring (such as translating NICHOLODEON into NICHOLODEONLINE) is also a transformation that produces various degrees of loss and gain. In other words, doubling produces systems of complexity. These issues of doubling and complexity are intrinsically related to questions of mapping; i.e., they question the ways in which the apparent surface interface of the computer is mapped across deeper programming languages and a foundation of zeros and ones. As Rita Raley argues, building on a point made by Friedrich Kittler (“There is No Software” 148), a “tower of programming languages” is produced (307)—a kind of architecture or structure of languages that map upon each other. These languages are all inevitably, as Hayles maintains throughout Chapter Two of How We Became Posthuman (1999), conceivable as “flickering signifiers.”

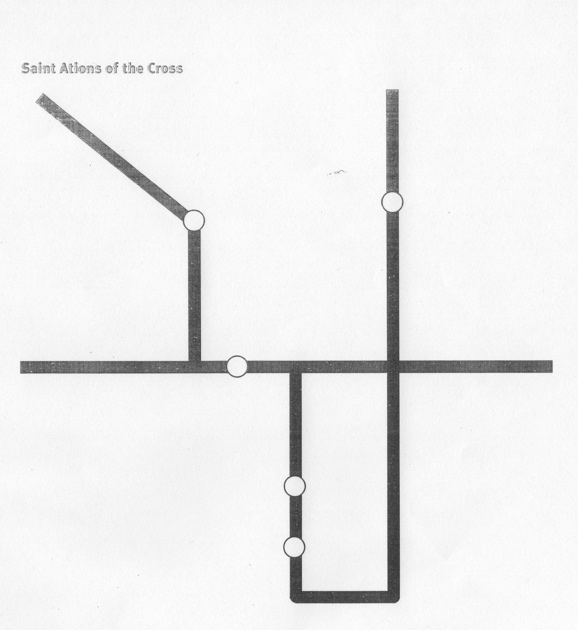

One of Wershler’s visual poems in NICHOLODEON presents the complicated dynamics of mapping and the potential poetico-theological implications of such a mapping. The poem is called “Saint Ations of the Cross”:

The source code for this image reads (on line 39): “St. Clair West, St. George, St. Patrick, St. Andrew, St. Clair.” This poem-map is an overlay of part of the TTC (Toronto Transit Commission) subway map for the city of Toronto—Nichol’s home for much of his life. The famously limited subway in Toronto—“limited” because it is far less expansive and less reliable than the subways of other large, metropolitan cities like New York, London, or Montréal—consists of two lines that intersect in what is roughly considered to be the middle of the city: the West-to-East “Bloor-Danforth line” and the North-to-South-to-North “Yonge-University line.” The subway stops that are shown at the circular points on Wershler’s map-poem are all of the Toronto subway station names that begin with “St.” The station stops beginning at the upper right of the map-poem and proceeding down or southbound on the “Yonge-University line” are: St. Clair West, St. George, St. Patrick, St. Andrew, and then proceeding down the line and back up north, St. Clair. This moment shows all streets from the TTC subway map that contain “saints.”

This concrete poem-map is connected to the complicated cosmogony of poetical saints that Nichol creates throughout his lifelong poem, The Martyrology (1972-1993), and that also appear at several other places in his oeuvre. “Saint Ations of the Cross” could also be said to depict a split-apart and reorganized Christian cross where the station stops (or “Saint Ation” “Saint Ops”) of the Toronto subway map are concerned—each point on the map could be considered the endpoints of the two intersecting lines that form a cross with the extra point being the middle point of intersection. As well, this map-poem manifests as a kind of living data pour that knots together, through a poetico-conceptual ganglion, Christian discourse, Nichol’s martyrology, and the general format of the Toronto subway map. This piece also implicates Nichol’s The Martyrology directly, especially Book 5, which is infused throughout with questions of place, such as when the streets of Toronto become central to the action of the poem; i.e., in one example, from a stand-alone page prior to the cover page, “blue” leads to “bluer,” which leads to “bloor” (n.p.). The saints from the earlier books of The Martyrology reappear on the streets of Toronto.

It is possible to speculate that a data pour is not necessarily digital. What I mean is that data pours have the potential to occur everywhere and wherever textuality is present or where there is some evidence of a textual clinamen. If there is a constraint that can be found, then there is likely a data pour that is present and this data pour persists throughout the manifested text like the material unconscious of a subsistent palimpsest.

It is important to note that Liu’s theory of the “data pour” is both transcendental and also material because the specificity of data transcendence means that the data that “pours” through a hyperlink is the result of an instance of an earlier form of materiality—the materiality of the database or of digital technology itself. This notion of materiality is not limited to the materiality of hardware, but also includes the programming language that produces and structures the pour. Therefore, there are many existent material-transcendentals that permit the kinds of data pours that frequently occur in digital poetry, electronic literature, or hyperlinked websites in general. The other type of data pour that I mention above relates to the ways that influence functions like a data pour; i.e., influence is a kind of data pour that permits the development of a poetical or authorial tradition. This second type of data pour can be called a subsistent instance of a material-transcendental. The semantic content of the code may be less clearly defined than in the more traditional example of hyperlinks, but a text is still nonetheless running in the background—it runs in the background of the human that has now become posthuman.

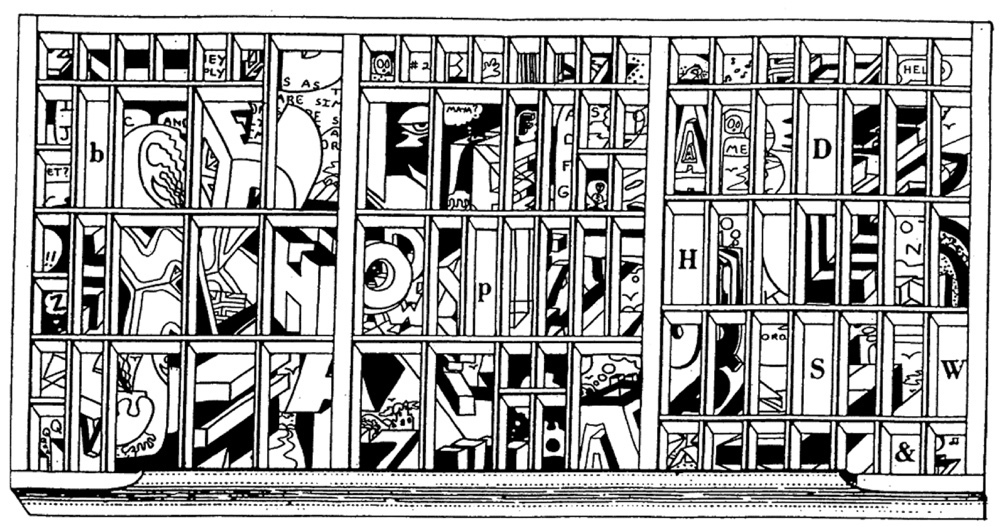

The center of NICHOLODEON contains a massive fold-out section called “Collected Allegories” that appears like a grid-like box. The box itself is a drawn representation of what is called a type case or a job case, which is a set of compartments in a larger box that contains the type that is used in letterpress printing—each letter of a printing press is, in this sense, a material object. Typically, a job case consists of two dominant sections for either uppercase or lowercase type with each having distinct sections for differently sized capital letters, braces, and fractions in the uppercase, or small letters, spaces, quadrats, etc., in the lowercase. There have been many different job case designs throughout history, but the one used by Wershler for “Collected Allegories” is a California job case, which is generally considered to be an improvement on the earlier designs of job cases; the primary innovation of the California job case is that it combines the uppercase and the lowercase boxes into one case without changing the position of the lower case letters (Ringwalt 95).

Unlike a traditional California job case though, “Collected Allegories” features an empty bottom that functions like a window that looks onto a subterranean realm of language.

Nichol’s poetry collections regularly feature comic book drawings that contain the letters of the alphabet as characters or as massive landscapes while a ghostly figure moves inside them or interacts with them. This ghostly figure, called Milt the Morph, is a repeating character in Nichol’s comic book drawings and can possibly “morph” into other characters like Lonely Fred, Tommy the Turk, Captain Poetry, or even Milt the Morph himself. Wershler’s choice to name this piece “Collected Allegories” points to the fact that the job case contains, beneath it, all of the comic book drawings or visual poems that Nichol created for his Allegories series—collected in full in love: a book of remembrances (1974). Allegories consists of thirty-two visual poems that feature the letters of the alphabet in various configurations and knotted forms—often the letters betray an “inner life” or consciousness as they think about other letters (such as when the letter L thinks about “L” in a thought bubble from “Allegory #22”) or when they interact with Milt the Morph. The letters combine and permute throughout Allegories in a manner that is reminiscent to the ways that a shape can morph in the mathematical field of topology.

Allegories relates to Nichol’s visual poems in ABC: the aleph beth book (1971) and Aleph Unit (1973). Both of these short works feature a similar logic of the permutational and comic book quality of the alphabet. However, as Nichol points out in the “Afterword” to Aleph Unit, he composed Aleph Unit “following the principles i had first applied in the ALLEGORIES [Allegories was created before Aleph Unit, but was not published until 1974] of eliminating the frame as a compositional unit and thereby compressing what i had spread over a number of frames into one visual unit” (The Alphabet Game 47). It is important to note that one of Nichol’s goals with Allegories was, as he claims, to “eliminate the frame as a compositional unit” and yet, in Wershler’s “Collected Allegories,” a frame is reintroduced—the frame of the California job case, which links “Collected Allegories” not only to Nichol’s Allegories series, but also to the tradition of the printing press. It is of course the various presses used at the Coach House Press that brought much of Nichol’s work into the world. However, it is important to note that Allegories would not have required the use of a job case and would not have been letter-pressed. Therefore, this piece demonstrates a collision in the materiality of the printing press and the tension between the free-flowing conception of the alphabet as an abstract entity and its manifestation in the materiality of a printed book.

A somewhat impressionistic consideration of “Collected Allegories” could link it to the Oulipian interest in the mathematical conceit of the “knight’s tour,” which is a mathematical chess problem that models a knight’s moves across a chessboard in such a manner that the knight only makes contact with each square once. Georges Perec’s novel La Vie mode d’emploi (1978) or Life: A User’s Manual (1987) makes use of the progression of the knight’s tour for a 10x10 chessboard to structure the text. In mathematics, the knight’s tour is used for chessboards or for grids that do not match a standard chessboard, which contains 8x8 squares; for this reason, a perhaps whimsical linkage can be drawn between Perec and the Oulipo’s interest in the knight’s tour and applied to the California job case. NICHOLODEON and NICHOLODEONLINE contain a short series of visual poems called “Language: A User’s Manual” that situate Perec’s novel as an intertext, but explores a different set of visual conceits that are grounded in playful explorations of certain aspects of structuralist and poststructuralist notions of language.

There is more that can be found when considering “Collected Allegories” because the image also presents the “collected” Allegories as a subterranean realm of swerving and topological alphabetic potential. This subterranean alphabetic realm can be understood as the dynamic and reassembling notion of the “realphabet”—this is a concept that Nichol primarily discusses in “Rediscovery of the 22-Letter Alphabet” (the fourteenth entry in the “Probable Systems” series), which is collected in the special issue of Open Letter on “Canadian ”Pataphysics” (1980-1981). The linguistic-being of a realphabet peers back from the base of the California job case as if from an exterior dimension, threatening to leak into the reality of the present world, the world of the reader. Nichol considers the language-inside-language to be a “realphabet” (42). In the strict sense, Nichol’s realphabet historicizes the Semitic aleph-beth, which eventually leads to the modern alphabet: the realphabet is composed of pictorial signs that represent objects such as the ox-head or the aleph ( ) that will eventually become the vowel A. Nichol’s speculative ”pataphilology or ”pata-poetics are, in this case, working within a Cratylean tradition because his thesis here presumes a synchrony between word and world. For Nichol, the surface conventionalism of the Hellenized and Latinized alphabet betrays the Semitic alphabet that exists underneath; put differently, the existence of the realphabet subsists in spite of the existence and dominance of the modern alphabet. This ”pataphilological speculation theorizes a potential geology of language. I am extending the way Nichol conceived of the realphabet in “Rediscovery of the 22-Letter Alphabet”—i.e., the depiction of the realphabet in that piece is different from the drawn, comic-esque, and topological appearance of the letters in Allegories —but I would argue that there is a similarity in the ways that both approaches seek to remove the alphabet from its traditional confines as a tool for the use of humans and resituate it as an entity-in-itself or as something that is intrinsically real —perhaps this Nicholian realphabetic approach to letters can be said to evoke a directly living language. In this way, the alphabetic characters and places of Allegories reflect realphabetic qualities and fit well within a context of a speculative linguistics and a ”pataphilology that would have interested Nichol.

) that will eventually become the vowel A. Nichol’s speculative ”pataphilology or ”pata-poetics are, in this case, working within a Cratylean tradition because his thesis here presumes a synchrony between word and world. For Nichol, the surface conventionalism of the Hellenized and Latinized alphabet betrays the Semitic alphabet that exists underneath; put differently, the existence of the realphabet subsists in spite of the existence and dominance of the modern alphabet. This ”pataphilological speculation theorizes a potential geology of language. I am extending the way Nichol conceived of the realphabet in “Rediscovery of the 22-Letter Alphabet”—i.e., the depiction of the realphabet in that piece is different from the drawn, comic-esque, and topological appearance of the letters in Allegories —but I would argue that there is a similarity in the ways that both approaches seek to remove the alphabet from its traditional confines as a tool for the use of humans and resituate it as an entity-in-itself or as something that is intrinsically real —perhaps this Nicholian realphabetic approach to letters can be said to evoke a directly living language. In this way, the alphabetic characters and places of Allegories reflect realphabetic qualities and fit well within a context of a speculative linguistics and a ”pataphilology that would have interested Nichol.

“Collected Allegories” not only depicts the realphabetic world that Nichol develops in his poetry and comic book poems, but it also manifests as a suggested or allegorical data pour; put differently, the permutational existence of the Nicholian realphabet leaks into the world through the material constraints of the printing press and permits the novel configurations of poetry. To that end, Wershler’s “Collected Allegories” collects Nichol’s Allegories series and reintroduces a comic book frame that Nichol chose to originally discard or push beyond. “Collected Allegories” also deploys the reintroduced comic book frame via the “architecture” of the California job case. Wershler’s piece works in the context of his homage to Nichol and it would also fit in the tradition of Nichol’s oeuvre because it is, at its essence, playful and ludic as well as being simultaneously serious, speculative, poetic, ”pataphysical, and funny.

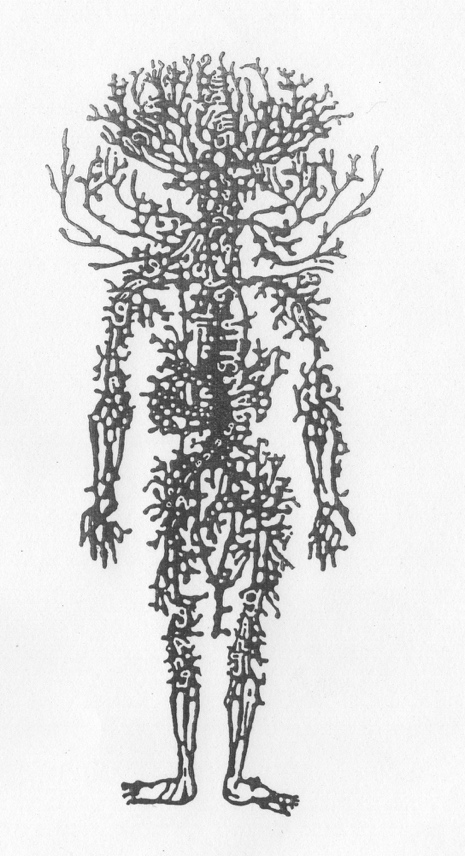

I would like to conclude by considering a final piece from NICHOLODEON and NICHOLODEONLINE: the concrete poem “Ganglia.” This piece presents a poet’s nervous system—it is called “Portrait of the Artist as a Nervous System” on line 39 of the source code—and features the general quality of both Nichol’s oeuvre and Wershler’s homage because the various nerves in the concrete poem proliferate like a kind of realphabet. The word “ganglia” appears at several places throughout “the artist’s” body.

The piece also resonates with Nichol’s interest in “zygals,” which are cerebral formations that connect two parallel fissures in the shape of an “H.” A zygal can be considered an anatomical instance of ganglia because both are anatomical points of intersection. “Ganglia” expands and is structured by the various electrical signals that function like insistent “data pours”—the data pours of the brain.

For writers like Nichol and Wershler, Canada becomes Canadada —a land of permutational potential and linguistic possibility. The trajectory from Nichol’s work to Wershler’s NICHOLODEON and NICHOLODEONLINE is more than a timeline of influence because it is also a textual ganglion of intersecting modes of writing, literary traditions, and influences. Such a ganglion is a depiction of the difficulties of influence in any poetic work and it also appears as a ludic history of a certain kind of “avant-garde” experimental writing in Canada. This particular ganglion of influence and creation is akin to the geological and sedimentary formations of the Canadian landscape as it intersects with the unforgiving wilderness and the growing metropolises of Calgary, Vancouver, Montréal, and Toronto. As well, this “ganglion” that I have been discussing also presents as the transition from the materiality of print to the materiality of the digital—a transition to e-CanLit.

WORKS CITED

Becker, Daniel Levin. Many Subtle Channels: In Praise of Potential Literature. Cambridge: Harvard UP, 2012. Print.

Bök, Christian. Crystallography. Toronto: Coach House, 2006. Print.

---. “Nickel Linoleum.” Open Letter: bpNichol + 10 10.4 (1998): 62-74. Print.

Bolter, Jay David, and Richard Grusin. Remediation: Understanding New Media. Cambridge: MIT, 2000. Print.

Braune, Sean. “Enantiomorphosis and the Canadian Avant-Garde: Reading Christian Bök,

Darren Wershler, and Jeramy Dodds.” Canadian Literature 210/211 (2012): 190-206. Print.

Drucker, Johanna. The Alphabetic Labyrinth: The Letters in History and Imagination. London, UK: Thames and Hudson, 1999. Print.

Foer, Jonathan Safran. Tree of Codes. New York: Visual Editions, 2010. Print.

Galen. Galen on Anatomical Procedures: The Later Books. Trans. Wynfrid Laurence Henry

Duckworth. Ed. M.C. Lyons and B. Towers. London: Cambridge UP, 1962. Print.

Hayles, N. Katherine. How We Became Posthuman: Virtual Bodies in Cybernetics, Literature, and Informatics. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1999. Print.

---. How We Think: Digital Media and Contemporary Technogenesis. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1. Print.

Jarry, Alfred. Exploits & Opinions of Dr. Faustroll, Pataphysician. 1911. Cambridge: Exact Change, 1996. Print.

Kittler, Friedrich. “There is No Software.” Literature, Media, Information Systems: Essays. By

Friedrich A. Kittler. Ed. John Johnston. Amsterdam: G&B Arts International, 1997. 147-155. Print.

Liu, Alan. “The End of the End of the Book: Dead Books, Lively Margins, and Social

Computing.” The Michigan Quarterly Review Fall (2009): 499-520. Print.

---. “Transcendental Data: Toward a Cultural History and Aesthetics of the New Encoded

Discourse.” Critical Inquiry 31.1 (2004): 49-84. Print.

Lucretius. On the Nature of Things: De rerum natura. Ed. and trans. Anthony M. Esolen. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins UP, 1995. Print.

Mauro, Aaron. “Versioning Loss: Jonathan Safran Foer’s Tree of Codes and the Materiality of Digital Publishing.” Digital Humanities Quarterly 8.4 (2014): np. Web. 3 October 2017. .

McCaffery, Steve. “Nichol’s Graphic Cratylism.” At the Corner of Mundane and Sacred: a bpNichol Symposium. Avant Canada: Artists, Prophets, Revolutionaries. Niagara Artists Centre. 7 Nov. 2014. Conference Paper.

Motte, Jr., Warren F. Introduction. Oulipo: A Primer of Potential Literature. Trans. and ed.

Warren F. Motte, Jr. Lincoln: Dalkey, 1998. 1-22. Print.

Nichol, bp. a book of variations: love—zygal—art facts. Ed. Stephen Voyce. Toronto: Coach House Books, 2013. Print.

---. bpNichol Comics. Ed. Carl Peters. Vancouver: Talonbooks, 2002. Print.

---. First Screening: Computer Poems. N.p.: 1984. http://vispo.com/bp/firstscreening.mp4.

---. The Martyrology: Book 5. Toronto: Coach House Press, 1982. Print.

---. The Alphabet Game: a bpNichol reader. Ed. Darren Wershler-Henry and Lori Emerson. Toronto: Coach House Books, 2007. Print.

---. Translating Translating Apollinaire: A Preliminary Report from a Book of Research. Wisconsin: Membrane Press, 1979. Print.

Open Letter: Canadian ”Pataphysics 6 and 7 (1980-1981). Print.

Perec, Georges. La Vie mode d’emploi. Paris: Editions Hachette Littérature, 1978. Print.

---. Life: A User’s Manual. Trans. David Bellos. Boston: David R. Godine, 1987. Print.

Powell, Barry B. Writing: Theory and History of the Technology of Civilization. West Sussex, UK: Wiley-Blackwell, 2012. Print.

Raley, Rita. “Machine Translation and Global English.” The Yale Journal of Criticism 16.2 (2003): 291-313. Print.

Ringwalt, J. Luther, ed. American Encyclopædia of Printing. Philadelphia: Menamin & Ringwalt, 1871. Print.

Schulz, Bruno. The Street of Crocodiles and Other Stories. 1934. Trans. Celina Wieniewska. New York: Penguin Books Ltd., 2008. Print.

Spinosa, Dani. Anarchists in the Academy: Machines and Free Readers in Experimental Poetry. Alberta: U of Alberta P, 2018. Print.

Wershler-Henry, Darren. NICHOLODEON: a book of lowerglyphs. Toronto: Coach House Books, 1997. Print.

---. NICHOLODEONLINE. Toronto: Collections Canada, 1998. http://www.collectionscanada.gc.ca/eppp-archive/100/200/300/chbooks/online/nicholodeon/index.html. 1998. 8 Oct. 2017.

Cite this article

Braune, Sean. "Digital Ganglia and Darren Wershler’s “Nicholphilia"" Electronic Book Review, 7 February 2021, https://doi.org/10.7273/5x7n-pz03