Electronic literature as a method and as a disseminative tool for environmental calamity through a case study of digital poetry ‘Lost water! Remains Scape?’

Reflections on an emerging digital poetry whose primary theme is ecological loss, and personal reminiscence.

The terms “making” and “building” have circulated for some years in the field of Digital Humanities (see Drucker 2009; Svensson 2010; Stephen and Rockwell 2012; Klein 2017; Endres 2017). These terms indicate empirical and pragmatic approaches and have brought a paradigm shift in the graphic tools and digital technologies used for visualization. These approaches in the humanities deploy the information and innovative visualizations to reinforce and supplement the conventional hermeneutics. This transformation is underpinned by interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary collaboration and brings together a range of stakeholders and experts from different fields such as writers, artists, researchers, and the public. Scholars such as Pawlicka discuss the transformation in the humanities through its instrumentation and practical turn during the period of humanities crisis in the west that ratifies humanities disciplines as invariably useful and intrinsically valuable to the society (Pawlicka 4-7). The digital turn in this century has not only transformed research and teaching in the humanities but has also changed our ways of reading, writing and creating things. In short, the digital has fundamentally reordered the praxis of literature. Scott Rettberg and Roderick Coover in their article “Addressing Significant Societal Challenges Through Critical Digital Media” discuss the Norwegian government’s proposal that the humanities can “engage more directly with “great societal challenges,” such as climate change, mass migration, and how we as a society are adjusting to the digital turn” (2020). They argue that electronic literature and digital arts have a vital role in addressing the above-mentioned problems through their own collaborative cinematic and computational narratives that address the issue of climate change. In this essay we guage the capacity of both digital humanities and electronic literature to address the contemporary crisis and challenges for societal changes. In particular, we argue that affective, collaborative digital media can be mobilized to mitigate environmental calamity. We ask how the adoption/integration of digital literary method can be an effective agency and actor to represent environmental concerns and disseminate environmental research for targeted audiences?

Although the discussions described above are crucial for the conversation, they are grounded in the western context. This observation leads us to the question of how tools and methods can contribute to the digital humanities and digital literature grounded in materials from the global south. The main aim of this paper is to explore the digital literary method as an effective agency to communicate the research findings to the broader public through a case study of our digital poetry: ‘Lost water! Remainscape?’ This poetry was one of the outcomes from the project ‘Digital Innovation in the Water Scarcity in Coimbatore, India’ at Lancaster University. In what follows we first endeavor to describe and theorize electronic literature as a method and disseminative tool for contemporary environmental challenges and issues. Secondly, we discuss the situatedness of digital humanities and electronic literature in India, focusing on the case study of digital poetry: ‘Lost water! Remainscape?’.

Electronic literature as a method and as a disseminative tool for the environmental issues

Both digital humanities and digital literature originated through experimentation in the West. Digital Humanities began with Robert Busa’s experimentation with computers for creating the Index for Thomas Aquinas’ works (Burdick et al. 123). Similarly electronic literature emerged from Christopher Strachey and Theo Lutz’s creative experiments using computer in the mid-twentieth century (Funkhouser 37). Later both disciplinary fields were established through support from the institutions, funding schemes, courses and programmes and widespread research activities. But these may look like two distinct fields based on their fundamental approach towards creativity as one is producing creative works and another is applying creative methods to study works of humanities disciplines. However, electronic literature is part of digital humanities. For example, digital humanities can adopt the creative practice for building its method, organization and production. Electronic literature can also be a more instrumental approach for widening digital humanities’ praxis. In the panel “Intersectional Scholarship in Electronic Literature and Digital Humanities” of the Association of Digital Humanities Organizations conference (2016), Élika Ortega proposed that electronic literature offers a model for digital humanities praxis in terms of exploring and addressing “the effect of digital media as it has modified––and continues to propose a modification of––reading and writing practices as well as modes of abstracting, encoding, and communicating information” (Ortega et al. “Intersectional Scholarship in Electronic Literature and Digital Humanities”). Such approaches can be deployed to critically visualize and disseminate the digital born creative works to represent the environmental problems and can be used as a catalyst to bring the change in the social issues.

Scholars and artists such as J. R. Carpenter, Scott Rettberg, Roderick Coover, António Abernú, Andy Campbell, Eugenio Tisselli, Richard A Carter, Tina Escaja and Paulo Silva Pereira are engaged in using digital art and literature to capture environmental crises in their own unique way. For example, J. R. Carpenter’s ‘In The Gathering Cloud’ and ‘This is a Picture of Wind’ call attention to the impact of man-made environmental degradation and climate change. The former narrates the environmental impact on cloud-storage and the latter contains the narratives about climate change that triggered winter storms in South West England. Similarly, Scott and Roderick’s ‘Toxi•City: a Climate Change Narrative’ addresses flooding, pollution and chemical exposure in post-industrial settings. In the panel ‘Ecologies’ at the ELO 2019 conference in Cork, Richard, Tina and Silva Pereira examined “the intersection between digital creativity and ecological thematics, dynamics, and materialities” (Silva Pereira “Greening the Digital Muse”). Studying and producing literature pertaining to environmental concern is not a new phenomenon. Coover and Rettberg compare electronic literature to novels and observe that both carry the “cultural values, political debates, and societal challenges of the time in which they were produced”. In terms of the apparent capacity of digital literature to disseminate the results of scholarly enquiry, they also assert that “artworks that are conceived first and foremost as the communication of scientific research or as ideological statements tend to fall flat” (Rettberg and Roderick “Addressing Significant Societal Challenges Through Critical Digital Media”). We concur that electronic literary work employed as propaganda for scientific research is unlikely to find traction with non-academic audiences. Rather we argue that integrating electronic literature as a creative method can enhance and enrich, simultaneously, both findings and dissemination. One of the specific knacks of electronic literature is that it can function as a conduit between the artistic expression, artefact, creator and reader. The creator can invite the reader to play, read, explore through the digital literary entities and its expression. These properties allow readers to become an agent within the narrative and narration of the text. It is that aspect that brings together many diverse audiences including scholars, students, experts, NGOs, policymakers, and more importantly the public. This compelling dissemination method can amplify the cognizance about the environmental challenges, grapple with its issues, and rethink environmental flux in the physical world.

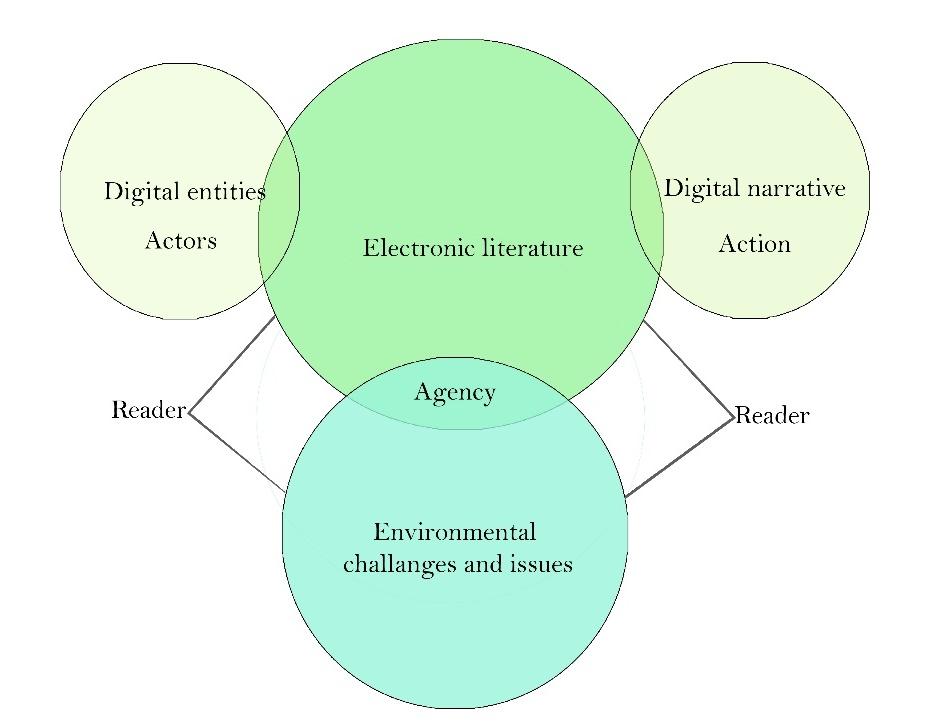

The dynamic, malleable nature of electronic literature means that its digital literary entities can function as an agency and actors (see Fig.1). As an agency between the user and creator, electronic literature is a conduit and platform through which plans for action can be formulated. The array of dynamic digital literary entities such as kinetic texts, images, videos, graphics, maps and other entities become actors and their narrative becomes the action of what functions as an impetus to bring positive societal change and to spark the critical thinking and decision making about environmental problems. The techniques and modes of expression of electronic literature may vary from one to another, “but the ability to address contemporary problems is unquestionable” (Silva Pereira “Greening the Digital Muse”). In the digital era, digital positivism and plurality disseminate electronic literature more efficiently and effectively as they can find many platforms to reach their targeted audiences such as social media and other digital platforms.

Situatedness of Digital Humanities and Electronic Literature in India

Digital Humanities in India is currently advancing remarkably as we can see from many national and international collaborative projects, programmes and courses, digital humanities departments and labs, government funding schemes (SPARC and IMPRINT), conferences and workshops and many more scholarly activities (Shanmugapriya and Menon para 1). Digital Humanities in India started off with archival projects. Of course, these archival projects are of paramount importance for widening the access to the cultural heritage. As we are in the progressive stage, we acknowledge that we still need to go a long way to achieve the items in our Digital Humanities resolution list such as adequate archives, sufficient digitized corpi and technical competencies and equality, Digital Humanities pedagogy, open access and many more. The particular challenges faced in India do not preclude the need to widen our vision to incorporate and adopt new methods and studies in digital humanities research and teaching, nor do they imply that India is at an apprenticeship stage of DH ‘development’. Indian electronic literature has begun receiving more attention from scholars and institutions. For example, the first Indian Electronic Literature Anthology publication from KSHIP at Indian Institute of Technology Indore. Indian electronic literary scholar Samya Brata Roy started an Elit India Whatsapp group which connects more than one hundred electronic literary scholars across the country and world. He is organizing a panel on ‘Literature and the Electronic in the Global South: Affordances and Complications’ in the upcoming third digital humanities conference of DHARTI in 2022. Scholars like Samya and others actively engage in studying the impact of digital culture on Indian literary praxis.

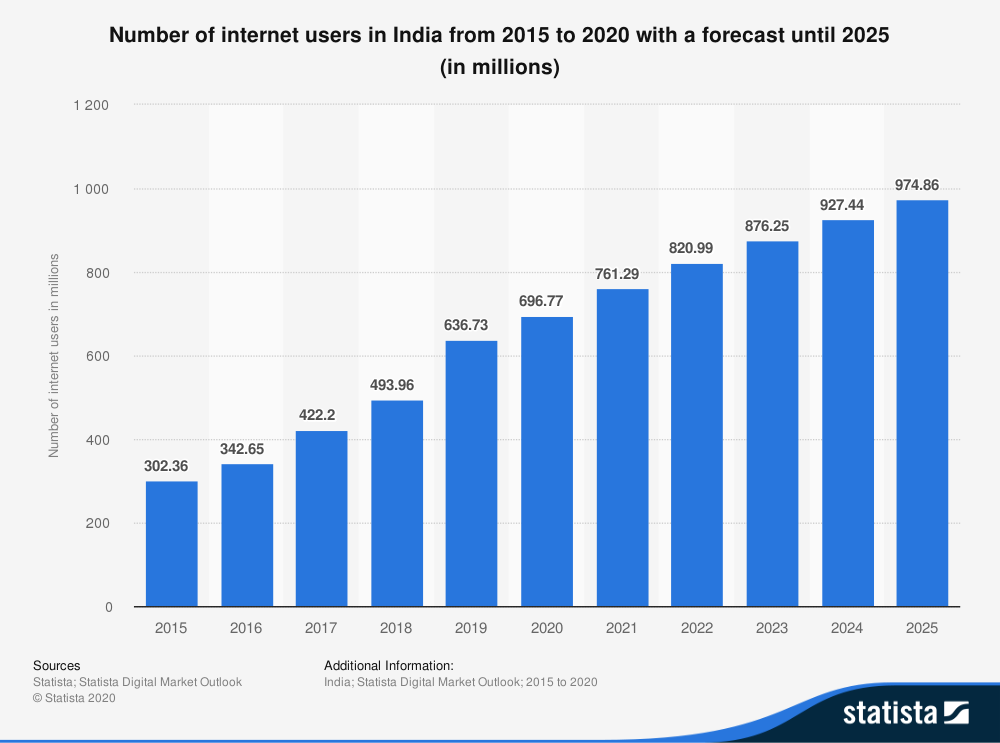

The recent Digital India movement has “a vision to transform India into a digitally empowered society and knowledge economy”. The vision areas also include ‘[a]vailability of high speed internet’ and ‘universal digital literacy’(“Vision of Digital India”). If we look at the number of Internet users in India, which is increasing tremendously, Indian digital humanists can harness this facility of outreach through critical and creative works (see Fig.2). The best example we can think of for interlinking the electronic literature and digital humanities for the Indian context is the Story writing machine in the novel The Vendor of Sweets by R.K. Narayan (Narayan 74). The novel was published in the mid-20th century. The author introduces a machine which can provide a formula for the story by clicking a few buttons of themes like love, revenge and hate and the interesting part is once the story is produced, the author can again use the machine for the text analysis of the story which is of course one of the cutting-edge features of digital humanities nowadays. What we are trying to say is that, like the story writing machine, both the creative practice and scholarly practice of electronic literature and digital humanities have more affinity and are capable of blurring the boundaries between humanities disciplines.

There are many ways digital humanities outputs can be mediated through interactive narrative forms of creative work. For example, Srinjoy Ghosh and Kshitij Gajapure’s “HyperPoetry Level 1” was “an initial attempt to bridge the philosophical thought of ‘Continuum Theory’ and the concept of Hypertext through the use of poems that have the subject matter of ‘infinity’ as its core”(Gajapure “HyperPoetry-Level-1”). Padmini Ray Murray’s Darshan Diversion is an example of both electronic literature and digital humanities (“Priests stop menstruating women from entering a temple. No, it’s not Sabarimala – it’s a video game”) because it uses technology creatively to address social issues. The narrative is about the prohibition of entry of menstrual women into a temple in the southern part of India. These projects manifest how digital humanities and electronic literature can underpin each other in many ways. Shanmugapriya T, the first author of this paper, has been in the fields of electronic literature and digital humanities for several years, and was working as a farmer for eleven years and having first-hand experience in the water issues in the selected geographical focus of the project helped in attaining the digital poetry ‘Lost water! Remainscape?’

‘Lost water! Remainscape?’

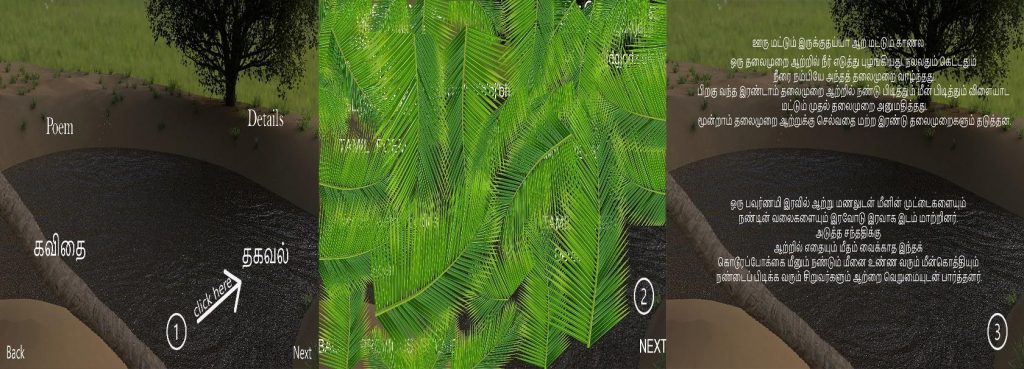

The digital poetry ‘Lost water! Remainscape?’ is written in Tamil by Jagadeesh and in English by Shanmugapriya T. It is created using 2D and 3D environments, and photos in Blender and Adobe Animate CC software. The 2D and 3D environments in the poetry reflect the narrative about the ecosystem of waterscapes in the past, and the photo animations represent the current situation of the water bodies in Coimbatore, the southernmost region in South India. This poetry is created based on the outputs from our AHRC funded project ‘Digital Innovation in Water Scarcity in Coimbatore, India’. This interdisciplinary project investigates the changed waterscape in Coimbatore, South India across 150 years by studying a range of materials and activities that include historical maps and satellite imagery, and conducting interviews with local farmers, activists and NGOs.

The report by the World Resources Institute says that India ranks seventeenth among countries confronting extreme high-water stress (Hofste and Schleifer “17 Countries, Home to One-Quarter of the World’s Population, Face Extremely High Water Stress”). Coimbatore has had frequent and severe droughts in the past four decades. Coimbatore region was under the Madras Presidency in British India and was divided into four districts of Coimbatore, Erode, Triupur and Karur in independent India. The water crisis in the region is the amalgamation of climate change, poor management, and unplanned development. The region had poor water depletion and was classified as ‘drought prone,’ in the 1970s (Priya K. L. et al. 448). Many lakes and tanks in the region have been encroached or are near-extinct. This transformation in water bodies, combined with the rapid population growth, have led to a massive imbalance between the annual supply and demand for water. Our research project has two principal strands: firstly, to draw together a large, digital corpus of graphic and textual information about the history of water in the region and, secondly, to work with local activists to design dynamic visualizations and narrations based on that corpus. The Survey of India maps of Southern India archived in the National Library of Scotland have been digitized as part of the project (https://maps.nls.uk/india/survey-of-india/). The georeferenced maps allow the user to explore the past and cartographic presence of water bodies over the past hundred years. For example, users can explore the transformation of perennial water bodies to dry lands and dry lands to concrete lands and roads. Insofar, twenty disappeared tanks and fifty shrinking water bodies have been identified. The analysis shows that most of the disappeared tanks are small ones which are encroached and occupied by houses and agricultural lands. The shrinking tanks are the larger ones which have been encroached by buildings and farming around the tanks. The text mining of the collected corpus of British India texts is underway.

Interactions with local farmers, activists, writers and NGOs are key to our analysis and visualizations. These interactions allow us to document water narratives from the local people. These narratives are the means by which our analysis and visualizations can meaningfully respond to and reflect lived experiences of water crisis in the region. Although inhibited by the Covid pandemic, our ethnographic study collects narratives about specific water bodies and about materials near and associated with water (pumps, wells, tanks, lithic epigraphy). Our aim is to re-situate the disembodied corpus of textual and graphic materials within the everyday realms of water scarcity. The prominence of nostalgia in these narratives for lost and absent water was key in connecting our data sets with contemporary scarcity. The digital poetry will reflect both the outcomes from the mapand the narratives from the local interviews and poetry about the past and current condition of water bodies in both Tamil and English. It also contains information about the water bodies in the past which are extracted from the historical texts such as Pulavar Rasau’s Kongu Aivugal (2018) and Tamil classic literary works.

Reminiscence is the primary theme of our digital poetry. It will be mediated through text, animations and images. Waterscape is an imperative source and forms a connective ecological community in every village of the region Coimbatore. It is a primary source for drinking, irrigation and other economic and cultural activities. However, the forgotten waterscapes due to drought, dereliction and climate change have become conduits of drainage waters, and garbage dumping areas. The photos taken during our field visits depict the current condition of water bodies among which most of them are in a dreadful state. In contrast to these images, the oral testimonies of the local farmers illustrate a different situation of waterscapes a few decades ago. They narrated how they were blessed to have had a healthy waterscape in the past. They also told us that particular flora and fauna that belong to the region had been destroyed. The interactive 2D and 3D environment of digital poetry will provide a revisitation to such lost waterscapes. It will also portray the current condition of waterscapes through photo animation and text narration. This digital poetry will be disseminated to students, scholars, activists and the general public through our academic and NGO partners and local schools and colleges. Feedback and some of the interviews conducted will be made available via the project website. The poetry is divided into five sections: Instructions, Historical Map, 3D River, 3D Water Tanks and Photo Animation. The first section will provide instructions on how to read and navigate the poetry.

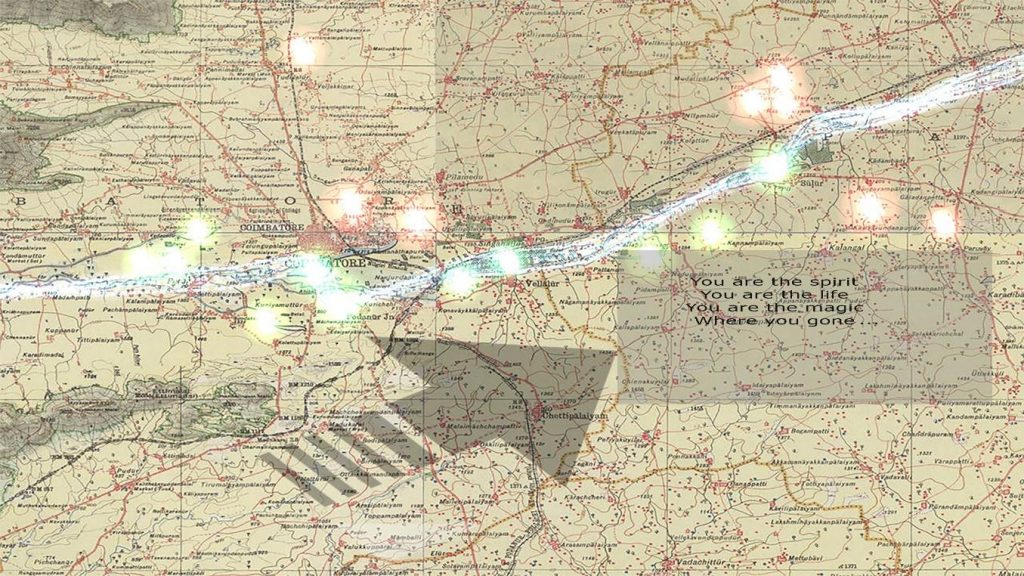

Historical Map

The below image shows the British India historical map and the shiny element represents the rivers and tanks in the region (see Fig.3). This stage is divided into four layers based on the segregation of the Coimbatore region: Coimbatore, Erode, Tripur and Karur. Each layer visualizes the rivers and the disappearing and shrinking tanks in the district. The white colour represents rivers, the red colour is disappeared tanks, and green colour is shrinking tanks. The poem and the information about the tanks are implanted in the arrow images which will pop up when the reader moves the cursor near to them.

3D River

The 3D River embodied the features of waterscape such as the flowing water, fish, butterflies and trees. It endeavours to portray the beautiful landscape of the river Coimbatore once had in the past (see Fig.4). The poetical lines in the Figure 4 narrates how Noyyal fills smoothly the tanks that were built alongside of its course. This animation will revisit the past and the poetry will arouse the emotions and reimagine the waterscape through both the rhetoric of visuals and words. The 3D River will provide some intriguing details about the rivers and tanks in the region which are extracted from the ethnographic study, historical texts and literature. For example, the interviewee N.Aruchamy painted a series of local stories about rivers which become agents of sentience and culture. He says that the rivers Cauvery and Bhavani join at Kooduthurai in Erode; however, the locals believe that another river called ‘Amirtha nathi’ also joins with these rivers beneath the water’s surface. In Pathittrupathau, one of the eight anthologies in Sangam literature (Tamil Classic literature), praises the rivers in the Kongu (Coimbatore) region as it is not uncommon to see the fragrance Sandalwood floats in Bhavani River, and if women lose their jewels while bathing in Bhavani, they can easily find them as the river was pure and crystal clear. During summer, people play water sports on the shore of Noyyal river (Rasu 20). The narratives not only celebrate the rivers. They also show how the rivers were a part of people’s lives.

3D Water Tanks

This animation illustrates the function of the tank system in the early period (see Fig.5). It provides information about the 30 historical tanks and 23 anicuts of Noyyal river that were built during the Karikala Chola period in 9th century to store its surplus water, and to avoid flooding in the region and how this breathtaking engineering technique kept the ground water level high. In Kongu Aivugal (2018), Pulavar Rasu writes that in total, there were 90 dams in Kongunadu (Coimbatore) according to Copper plates of Cheiftan Kalingrayan, who ruled part of Kongunadu and built a dam and a canal called Kalingrayan on Bhavani river to improve agriculture in Erode. There were 32 dams in Noyyal river, 20 in Amaravathi, 18 in Meenkolliyaru, 6 in Nallamangaiyaru, 4 in Bhavani, 4 in Upparu, 4 in Nankanji, and 4 in Kudavanru (125). Though a few dams and tanks are still in working condition, many are either damaged or encroached. Such information and poetry embedded in digital poetry narrates the functioning of the tank system in the past, and creates a cultural landscape of the local custom. Most of the local Hindu festivals begin and end with bringing water from these tanks which accentuate the pivotality of water in the cultural settings. The poem in the Figure 5 narrates change in the relationship between locals and rivers over three generations ending in the present (see Fig.5). The first generation depended on rivers for their survival and the second generation developed more connection with rivers as they catch fish and play sports on the shore. The current generation could not do anything as the rivers became dry. This poem also indicates the primary issue of river sand theft.

Photo animation

This stage has multiple layers of photo animation. The photos are taken during the field visits to the various water bodies. These pictures display the current condition of the water bodies alongside poetry and contextual information about the photo. The below image exemplifies the Panjapatti lake which is located in Karur. It is the third largest tank in Tamil Nadu and the original capacity of this tank was 1820 acres but it is now spread around 1300 acres. The foundation of the tank began in 1837 and the construction was completed in 1911 during the British colonial period. It was the principal source of water to 18 villages in and around Panjapatti village, Karur. However, it has been dried for 16 years due to climate change and mismanagement of the water body. The tank is now silted by sand and occupied by Prosopis juliflora plants. Overall, the technological advancements of electronic literature as a method of research projects that focus on the environmental crisis can open the door of new horizons which can accommodate and bring together researchers, artists, citizens and decision makers for positive change.

References

Burdick, Anne, Johanna Drucker, Peter Lunenfeld, Todd S. Presner, and Jeffrey T. Schnapp. Digital-humanities. The MIT Press, 2016.

Carpenter, J. R. The Gathering Cloud. Devon: Uniform Books, 2017. http://luckysoap.com/thegatheringcloud/

―. This is a Picture of Wind. IOTA: DATA, 2018. http://luckysoap.com/apictureofwind/

Coover, Roderick, and Scott Rettberg. Toxi•City: A Climate Change Narrative. CR Change Production, 2014. http://crchange.net/toxicity

Drucker, Johanna. SpecLab: Digital Aesthetics and Projects in Speculative Computing. University of Chicago Press, 2009.

Endres, Bill. “A Literacy of Building: Making in the Digital Humanities.” Making Things and Drawing Boundaries: Experiments in the Digital Humanities, edited by Jentery Sayers, University of Minnesota Press, 2017, pp. 44–54, doi:10.5749/j.ctt1pwt6wq.7.

Funkhouser, Chris. Prehistoric Digital Poetry an Archaeology of Forms, 1959-1995. The University of Alabama Press, 2007.

Gajapure, Kshitij . “HyperPoetry-Level-1”. 2018. https://github.com/Kshitij08/HyperPoetry-Level-1#readme

Hofste, R., Reig, and Schleifer, L. “17 Countries, Home to One-Quarter of the World’s Population, Face Extremely High Water Stress”, World Resource Institute, 2019. https://www.wri.org/insights/17-countries-home-one-quarter-worlds-population-face-extremely-high-water-stress

Klein, Julie Thompson. “The Boundary Work of Making in Digital Humanities.” Making Things and Drawing Boundaries: Experiments in the Digital Humanities, edited by Jentery Sayers, University of Minnesota Press, 2017, pp. 21–31, doi:10.5749/j.ctt1pwt6wq.4.

Narrayan. R.K. The Vendor of Sweets. Viking Press books, 1967.

Ortega, E., O’Sullivan, J., Grigar, D. (2016). Intersectional Scholarship in Electronic Literature and Digital Humanities. In Digital Humanities 2016: Conference Abstracts. Jagiellonian University & Pedagogical University, Kraków, pp. 82-85.

Pawlicka, Urszula. “Data, Collaboration, Laboratory: Bringing Concepts

from Science into Humanities Practice.” English Studies, vol. 98, no. 5, pp.526-5412017. doi: 10.1080/0013838X.2017.1332022

Priya, Jennifer, G., G. Thankam, S. Thankam and M. Mathew. “Monitoring the Pollution Intensity of Wetlands of Coimbatore, Tamil Nadu , India.” Nature Environment Pollution Technology, 12, no.3, 2011, pp. 447-454.

Ramsay, Stephen, and Geoffrey Rockwell. “Developing Things: Notes toward an Epistemology of Building in the Digital Humanities.” Debates in the Digital Humanities, edited by Matthew Gold, University of Minnesota Press, 2012, 75–84.

Ray, Padmini Murray. “Priests stop menstruating women from entering a temple. No, it’s not Sabarimala – it’s a video game”, Scroll, November 12, 2021.

Rettberg, Scott and Roderick Coover. “Addressing Significant Societal Challenges Through Critical Digital Media”, Electronic Book Review, August 2, 2020, doi:10.7273/1ma1-pk87.

Silva Pereira, Paulo. “Greening the Digital Muse: An Ecocritical Examination of Contemporary Digital Art and Literature”, Electronic Book Review, May 3, 2020, doi:10.7273/v30n-1a73.

Svensson, Patrik. “The Landscape of Digital Humanities.” Digital Humanities Quarterly, vol.4, no.1, 2010. http://digitalhumanities.org/dhq/vol/4/1/000080/000080.html#drucker2009a

T., Shanmugapriya and Nirmala Menon. “Infrastructure and Social Interaction: Situated Research Practices in Digital Humanities in India.” Digital Humanities Quarterly, vol. 14, no. 3, 2020. http://www.digitalhumanities.org/dhq/vol/14/3/000471/000471.html

“Vision of Digital India.” Digital India. N.d. https://www.digitalindia.gov.in/content/vision-and-vision-areas

Cite this article

T, Shanmugapriya and Deborah Sutton. "Electronic literature as a method and as a disseminative tool for environmental calamity through a case study of digital poetry ‘Lost water! Remains Scape?’" Electronic Book Review, 6 February 2022, https://doi.org/10.7273/8fce-9302