This is an informal essay, not a paper. There are simply too many questions and few answers. The text was assembled from notes from my keynote conference at ELO 2018 in Montreal ("Mind the Gap!"), where I have experimented with a tentative form of performing theory, possibly pushing the limits of Walter Benjamin's desire to write a book made of quotations only. Also, as with all things, this is an incomplete account of the use of humor and constraint in electronic literature. Many examples just simply could not be included here, and it is not my intention to perform close-readings of any of these works either. My goal is simply to create a narrative that signals how humor is related to constraint in art and technology. Perhaps we can prepare an Anthology of Humorous Electronic Literature together? Also, some disambiguation is in order: this is not about computational humor, or the use of computers in humor research, or about jokes concerning computers. And this is also not about OuLiPo or other literary works specifically written under constraint.[footnote]For a discussion about these type of works, read ebr's thread "Writing Under Constraint," edited by Joseph Tabbi at the turn of the millennium. https://electronicbookreview.com/essay/writing-under-constraint/[/footnote]

echo intro >/dev/null 2>&1 ; read

In the introduction of his book The sense of humor, Max Eastman states:

“This may seem a remote opening for a book about humor, but it happens that the problem of humor has always been a special field of play for the irresponsible essay-writer, and the literature that adorns it is notoriously inconsequential. When I told Bernard Shaw that I was writing this book, he advised me to go to a sanitarium. “There is no more dangerous literary symptom,” he said, “than a temptation to write about wit and humor. It indicates the total loss of both."" (viii).

This may as well seem a remote opening for a keynote – now transcoded into an informal essay – on humor, but I accept the risk and raise my bet, addressing not only humor, but humor and constraint. I admit that I feel somewhat embarrassed, as I have more questions than answers: does humor belong in e-lit?1 Is e-lit under pressure? What forms of control keep e-lit within particular limits, restraining its freedom? Can humor afford aesthetic and technological self-reflexivity? Is humor a form of overcoming constraints? How can we read and write in the post-digital world? How can we read and write in the current networked ecology of texts? Twenty years after Kittler declared that “There is no Software,” can we move beyond his pessimistic statement that “[w]hat remains a problem is only recognizing these layers which, like modern media technologies in general, have been explicitly contrived to evade perception. We simply do not know what our writing does” (1997, p. 148) in modern media technologies?

I understand humor and e-lit as acts of resistance, as categories of writing that appropriate, and not simply employ, forms of expression. Humor as self-reflexive practice that transforms constraints into freedom acts: freedom to demolish/ disassemble/ reveal the actual code(s) of writing; freedom to appropriate materials, reconverting them upon new contexts; freedom to integrate different material configurations. E-lit as the result of ingenious and creative work with technological apparatuses.

var humor = subversion, parody;

When I was doing my research on humor and constraint, a song by the Monty Python comedy troupe, “I Bet You They Won’t Play This Song on the Radio,” often came to mind. Performed by Eric Idle, it mocks radio censorship of words considered inappropriate, replacing them with beeps and comic sound-effect noises. Although profanity is thus abolished, it finds a way to be present. We know too well what those bleeps stand for: “You can’t say (bleep) on the radio, / Or (bleep) or (bleep) or (bleep). / You can’t even say I’d like to (bleep) you some day / Unless you’re a doctor with a very large (bleep).” The repressed always finds a way to resurface/return, even if unrecognizable. So why does this song matter? Firstly, because humor reveals the underlying constraint, it reflexively creates and disaggregates. Secondly, because the media cannot understand humor. It is curious how software bots planted an advisory message in this self-censored song! The metrolyrics website inserted a

tag right on top of the page with an Advisory stating: “[T]he following lyrics contain explicit language.”2 Obviously they don’t! Bots are blind to humor. And censors are blind bots. This song – which ironically played on the radio quite frequently – demonstrates how humor is able to overcome censorship, and how the implicit discourse is able to circumvent constraint and pressure.

Picking another fragment from popular culture, in the final scene of Batman: The Killing Joke, by Alan Moore (1988), Batman chases the Joker (again!), who runs, resisting arrest, and upon facing the ultimate crossroads, he shoots the Batman. However, his gun only discharges a “Bang” flag. A self-reflexive gun! As a last resort, he fires back with humor, the so-called final joke:

“See, there were these two guys in a lunatic asylum… and one night, one night they decide they don’t like living in an asylum any more. They decide they’re going to escape! So, like, they get up onto the roof, and there, just across this narrow gap, they see the rooftops of the town, stretching away in the moon light… stretching away to freedom. Now, the first guy, he jumps right across with no problem. But his friend, his friend didn’t dare make the leap. Y’see… Y’see, he’s afraid of falling. So then, the first guy has an idea… He says “Hey! I have my flashlight with me! I’ll shine it across the gap between the buildings. You can walk along the beam and join me!” B-but the second guy just shakes his head. He suh-says… He says “Wh-what do you think I am? Crazy? You’d turn it off when I was half way across!” (Moore 1988, n.p.)

To walk along the beam across a narrow gap: is this not what we do on the web? Isn’t this the nature of digital texts? The Joker (and humor) is the revelry, the embodiment of Carnival, making room for an inversion of hierarchies, accepting contradictions, integrating opposites, desecrating, resisting unification. And to write is to resist, it is the ability to destroy this (invisible) line. Julio Cortázar asked in his novel Rayuela, in 1963: “Para qué sirve un escritor si no para destruir la literatura? [What good is a writer if she can’t destroy literature?]” (2014, p. 463). And that is why we should further ask: does e-lit resist digital and digital writing constraints? Or does it conform to them, accommodating to templates? To use Umberto Eco’s (1964) distinction: is e-lit apocalyptic or integrated? Is it ironic, sarcastic, related to what Sloterdijk (1987) calls kynicism; or ideological, conformed, connected to cynicism?3

In his Le plaisir du Texte [The Pleasure of the Text], from 1973, Barthes lays down a frontier between texts that give pleasure and texts that yield bliss. A text of pleasure “contents, fills, grants euphoria; the text that comes from culture and does not break with it, is linked to a comfortable practice of reading” (1998, p. 14). You walk the Joker’s line of light, you cross the gap. The text of bliss (in French jouissance, also pleasure), on the other hand, places the reader in “a situation of loss (…) discomforts (…) unsettles” (p. 14), making foundations falter, turning our relationship with language into crisis. You understand that the line is a beam of light, you mind the gap. Humor is blissful; its nature is dionysiac, orgasmic.

Humor and the humorous, as Alleen and Don Nilsen explain, can be traced back to medieval physiology, in which “the bodily fluids, or humours, were described as yellow bile, black bile, phlegm, and blood. (…) If these bodily fluids were out of balance, a person would likely become emotionally unbalanced” (Nilsen and Nilsen 2008, p. 248). Out-of-balance folks were eccentrics, obsessed people who made normal people laugh. They are humorous characters (rather resembling the Joker), surprising and “absurd, ludicrous, or exaggerated.” (Nilsen and Nilsen 2008, p. 248).

Plato was a critic of laughter, treating it as “an emotion that overrides rational self-control.” (Morreall, n.p.). And in his ideal State, as Morreall also informs, comedy should be controlled, and “such representations be left to slaves or hired aliens.” Correspondingly, in the Bible, mockery is so offensive it is punishable by death. Morreall quotes from Kings: “He went up from there to Bethel and, as he was on his way, some small boys came out of the city and jeered at him, saying, “Get along with you, bald head, get along.” He turned round and looked at them and he cursed then in the name of the Lord; and two she-bears came out of a wood and mauled forty-two of them.” (2 Kings 2:23 apud Morreall). Dare not mock the baldness of prophets! This perspective, let us be clear, has “dominated Western thinking about laughter for two millennia”… (Morreall, n.p.).

For many, laughter still expresses feelings of superiority over others, or “violates our mental patterns and expectations” (Morreall), as theorized by Kant, Schopenhauer, or Kierkegaard. No wonder the academia is still unable to find any solemn intention in humor, interpreting it as inconsequential and irresponsible. Matt Kirschenbaum masters the history of e-lit, and he is knowledgeable enough to explain that e-lit has historically been defined, like prog-rock, by a “seriousness of purpose,” or “conceptual density.” These characteristics “have served to gain e-lit a firm institutional purchase in academia, where difficulty and seriousness are rewarded” (2018, p. 31), he explains. And the academy did have rewards: “jobs for some fortunate few, but also publication outlets, grants, endowments, office space, conference facilities, graduate assistants, students who could be “exposed” to the work, and more.” (31).

However, if humor is a complicated substance for academic fellows, the same cannot be said regarding the avant-gardes. The Dadaist babble, although seen as “the first neokynicism of the twentieth century” (1987, p. 391) by the German philosopher Peter Sloterdijk, is a good example of a specific chaotology, that of Cynical Reason and Semantic Cynicism. In an article on diabolic poetics suitably entitled “Humor — Technology — Gender,” Friedrich W. Block declared an affinity of comic aspects to reflexive or experimental art, arguing that “contemporary (media-) art per se tends towards humor.” (162). Adopting an argument of poietike techné (“poetics also self-referentially works as technology”), Block is interested in poetry that adapts to the culture of technology, and relates this to its own means and procedures, experimenting with technology, forcing us to make sense between restriction and freedom. According to Block, poetry, or language art, “raises the linguisticality of the technology culture, as well as existing and new language techniques, and acts these out, condenses and recontextualizes them—in short, contaminates them poetically” (171). Humor, which is not formed as an end in itself, is then “subversive and deconstructive” and all art in movement tends towards humor. Moreover, as Block notes, we should not forget that “art which lacks a sense of humor frequently seems to be rigid and suspected of ideology.” (171)

In her studies on parody, Linda Hutcheon has argued that parody constitutes a privileged mode of formal self-reflexivity because it incorporates the past by identifying the ideological contexts in which it can be perceived, critically addressing discourses from within, thus becoming “the mode of the marginalized, or of those who are fighting marginalization by a dominant ideology.” (1987, p. 206). Hutcheon further explains that ”(…) parody has certainly become a most popular and effective strategy of black,4 ethnic, and feminist artists,5 trying to come to terms with and to respond, critically and creatively, to the predominantly white, Anglo, male culture in which they find themselves. For both artists and their audiences, parody sets up a dialectical relation between identification and distance.” (206).

The clown (the Joker, the lunatic) is not a rigid character. Instead, it embodies the inversion of Royal properties, articulating irreverence and laughter, piracy and spree, sin and transgression. If we consider appropriation and remix, and other discursive forms disrupting the traditional order, Procrustes,6 the bandit who attacked passers-by, best represents our time.7 Known to lay the tall ones on a small bed, cutting off their feet so they would fit; and the short ones on a big bed, stretching them, this rogue smith leads us to ask: adapting text to template, adjusting content to form, is this not Procrustean?8 One size fits all, or rather, not everyone fits the mold? Mind the gap!: when we appropriate form, are we making it intelligible as form? By using the form of the sonnet in a different, unexpected manner, are we making its authoritarian form visible? Or are we being slaves to it?

By playing with form, mocking it and processing it, humor becomes the counterpart of tragedy. And tragedy, as Morreall explains, assessing the serious engagement with life’s problems, is a way of building stereotypes, those of the “Western heroic tradition that extols ideals, the willingness to fight for them, and honor. The tragic ethos is linked to patriarchy and militarism—many of its heroes are kings and conquerors—and it valorizes (…) blind obedience (…) resoluteness of purpose, and pride.” (Morreall 2016, n.p.). Comedy, on the contrary, embodies Carnival and leads to a carnivalization: subverting norms upside down and inside out. A narrow gap stretches away to freedom, as the Joker has taught us.

var constraints = rules, systems;

We are all aware that language and writing are rule-based systems. Because of that, as Manuel Portela explains, “[i]nsofar as language and writing are rule-based systems, a number of enabling constraints are already in place in any act of writing.” (2017, p. 181). “Language Is A Virus,” Laurie Anderson sings after William Burroughs. Language works under constraint, and literature, a creative and reflexive discourse on language(s), tries to move beyond and against constraint.

In “Post-Digital Literary Studies,” Florian Cramer (2016) explains that Saussure’s and Jakobson’s structuralist models of speech (the paradigmatic selection of elements and the syntagmatic combination of those selected elements) constitute (and establish) “a digital model of language.” (12). The alphabet, he argues, is an example of how digital information can be computable: “The alphabet is a digital system, since it consists of letters as its countable elements in a finite set.” (12). Language can thus be computable, and that is why “big data” technologies, as Cramer argues, can produce automatic translations, even “robot journalism” which uses statistics, but computer linguistic analysis is “doomed to fail when applied to any semantics that deviates from the norm.” (15). Poetry and complex grammars are a problem, as is humor and irony…

A similar constraint is identified by Johanna Drucker when describing an 1842 compendium of literary curiosities assembled by Gabriel Peignot, a collection of works and rules for their composition. Drucker contends that this compendium can be correlated with electronic, computational, and digital production of poetic works. Because they were written under constraint, “their rule-bound approach has an algorithmic character that can be compared with the compositional tactics used in computational work.” (2018, p. 27). Included in these digital-like works is a category that specifically consists of “works that flirt with double-meanings,” (30) leading Drucker to argue that the creation of parodies and burlesques in which semantic values have to be matched is too nuanced for mechanistic production: “Ambiguity, after all, is not an algorithmic strong point. Formal structures, rather than semantic complexity, lend themselves to automatic processes.” (30). In short, we can abstract a set of procedures from these inventories, but we cannot do the same with ambiguous discourses, for ambiguity [and humor] is not easily constrained. And yet language remains a constraint.9

The langue, for Saussure, lest not forget, is institutional: it imposes itself on each and every one of us, although we believe we are free to use it.10 And that is why in his Leçon [Lesson], Roland Barthes declared that the langue is simply fascist, in the sense that fascism is not to prevent one from saying, it is to oblige one to say (1978, p. 14).11

And how can we resist language? For Barthes, resistance is only possible outside the power of language [“hors du langage”], in its beyond, but this beyond does not exist, because there is no beyond or exterior to language: language is a hermetically closed place, enclosed… (Barthes 1978, p. 15). As Sylla explains (2015, p. 6), we need to resist within language itself, by creating non-places, u-topoi, i.e. places that are not detectable. The unlimited game with the material of language, a game that allows deluding language (what Barthes calls a salutary cheating, a magnificent lure), is thus revealed as poetry, a displacement, a permanent change of place, a textual flexibility with no fixed topos, utopic, nowhere to be found. (Sylla, 2015, p. 6).12 Resistance is a subversive power hiding within the entity it resists to (p. 7). This is why experimental language art resists “the dominant literature, official, consecrated” (Saraiva 1980, p. 5). It is marginal and marginalized because of literary ideologies and the “publishing market economy” (6), which have always acted as constraints. Literary marketing still fails to legitimate experimental forms of writing, unable to compartmentalize them in the molds set by the market.

Is this true for e-lit? Can it resist the automatization of language(s)? Jan Mukarovský explained in 1932: if “automatization schematizes an event; foregrounding means the violation of the scheme.”(1964, p. 19). Maybe we should now adapt Mukarovský: e-lit foregrounds the technical scheme of post-capitalist digital textuality. Not less than one hundred years ago, Victor Shklovsky also had a vision, a vision that is still very much provocative nowadays: “The purpose of art is to impart the sensation of things as they are perceived and not as they are known. The technique of art is to make objects ‘unfamiliar,’ to make forms difficult, to increase the difficulty and length of perception.”(1965, p. 12). To deautomatize or to estrange digital technologies and digital textualities is to fight the obsolescence of its forms. And difficulty should not be a problem: as per Barthes, literature puts us in a “situation of loss”, it “discomforts.”13

Joe Tabbi, introducing the Electronic Literature Organization’s recommendations for the Preservation, Archive and Dissemination of e-lit, advocated: “Those who neglect basic preservation issues very quickly discover the mess that technological obsolescence makes, not only of individual works, but of the connections among texts, images, and code-work that are crucial for any sustained, community-wide literary practice.” (2004, n.p.).14 We’ve been coping with this mess of obsolete e-lit: clearly, obsolescence is a constraint. “Acid-Free Bits,” the report by Nick Monfort and Noah Wardrip-Fruin (2004) that initiated these PAD activities, described the good practices we should keep in mind for maintaining e-lit alive (i.e., readable and accessible) - choose open systems over proprietary ones; consolidate, comment and distribute/share code, etc.

However, where obsolescence seems inevitable (“let them die!,” Jason Nelson once told me),15 and programmed obsolescence may read as a remote conspiracy, lock-ins are our current most critical issue. Jaron Lanier, in You Are Not a Gadget: Manifesto (2010), provides the example of the MIDI, which became the standard scheme to represent music in software, but soon became “entrenched.” Forms of forced standards are “a nuisance [even] before computers,” but software, Lanier argues, “is worse than railroads, because it must always adhere with absolute perfection to a boundlessly particular, arbitrary, tangled, intractable messiness. (…) So while lock-in may be a gangster in the world of railroads, it is an absolute tyrant in the digital world.” (8-9). Lock-ins in software happen when a particular design will “fill a niche and, once implemented, turn out to be unalterable,” becoming permanent (9). Lock-ins have a rigid, mandatory structure, they are “like a wave gradually washing over the rulebook of life” (10), obeying monopolies which are opaque and proprietary. An example: “Commercial interests promoted the widespread adoption of standardized designs like the blog, and these designs encouraged pseudonymity in at least some aspects of their designs, such as the comments, instead of the proud extroversion that characterized the first wave of web culture.” (14).

Participatory culture, interactivity, online cultures, they are all diminished by Lanier, who sees “trivial mashups” and “a culture of reaction without action.” (16), suggesting that constraints are important and even missing in our culture: “What is crucial about modernity is that structure and constraints were part of what sped up the process of technological development, not just pure openness and concessions to the collective.” (42).

Maybe we’ve been creating our own mythologies, placing the “digital” as what Barthes called our utopic non-places of ambiguity, transforming resistance into a constraint itself.16 The digital, thusly characterized as impermanent, fluid, open, variable, indeterminate, performative, featuring a structure of contingent centers, decenterable and recenterable (Bass 1999, p. 660), “expansive, dispersed, decentralized, [and] undisciplined” (662). Katherine Hayles has summoned this discourse on openness by calling upon a “new form of textuality”: electronic literature, that which is “dispersed rather than unitary, processual rather than object-like (…)” (2003, p. 276).

Portela explains that the literary production of our techno-social moment “has been automated, that is, many constrained procedures have become executable code.” (2017, p. 182). Nevertheless, constraints are reflexive and expressive tools, since they expose “the architecture of language as produced text and textual engine.” (183). Portela recalls Italo Calvino’s 1967 essay on “Cybernetics and ghosts” where the ideal writing machine is imagined as feeling the need to overthrow the own rules, and writes: “That will be one of the signs of the literary in a future of fully automated constrained, state-surveilled, and corporate-owned writing: a text that could not be accounted for solely or predominantly on the basis of its algorithm, that is, a text that could free itself from its constraint, a stochastic anomaly.” (192).

if (constraints){ humor }

If a stochastic anomaly – a text free from constraints – cannot be anticipated yet, maybe we can assign u-topoi to humor acts of transgression: performing on redundant structures, forcing unexpected configurations.17 Language art can foreground the technological apparatuses that circumscribe current writing tools and mechanisms; and humor may well be the par excellence device to guarantee such a strategy. Poetry does resist myth, constituting a regressive semiological system, as Barthes explained: “Whereas myth aims at an ultra-signification, at the amplification of a first system, poetry, on the contrary, attempts to regain an infra-signification, a pre-semiological state of language (…)” (1972, p. 133). Poetry is an “anti-language,” or at least a “murder of language, (…) analogue of silence.” (134). And if myth transcends into a factual system, then poetry contracts into an essential system (134). If Parody, as critical distance, is added to the poetic equation, then we move into open horizons, beyond and against constraints. Aurature, as John Cayley (2018) proposes, could perhaps resist myth, constituting a regressive semiological system, as Barthes explained.

Philippe Bootz’s aesthetics of frustration, i.e., to read the reading, which implies a double reading, may support this argument: deception, frustration, failure (2001); whatever writers try to avoid, e-lit can put into practice. That is probably why electronic literature is defined by Bouchardon as the result of various creative tensions: tensions between media types and platforms, between distinct semiotic forms, between computer programming and writing (Bouchardon 2017, p. 6).

Recalling the Monty Pythoncomedy troupe, Rob Wittig’s essay on “Literature and Netprov in Social Media” explains that to reuse styles in a fictionalized way implies their entrance in culture as new, spontaneous voices. Citing the Monty Python’s explicit references to TV conventions, Wittig quotes his favorite example: ”(…) like other half—hour comedies of its time, Monty Python was mostly shot on video, but had budget for a certain amount of more expensive shooting on film, which was usually used for exteriors. In one episode, a character repeatedly goes from indoors to outdoors, loudly marveling at the fact that inside he is on video and outdoors he is on film.” (2017, p. 122-23). Wittig uses this example to conclude that technological self—awareness becomes political self-awareness. Much like the radio song that won’t play on the radio, this is a “method to make the invisible visible, (…) a kind of structural satire that provokes structural insight.” (123).

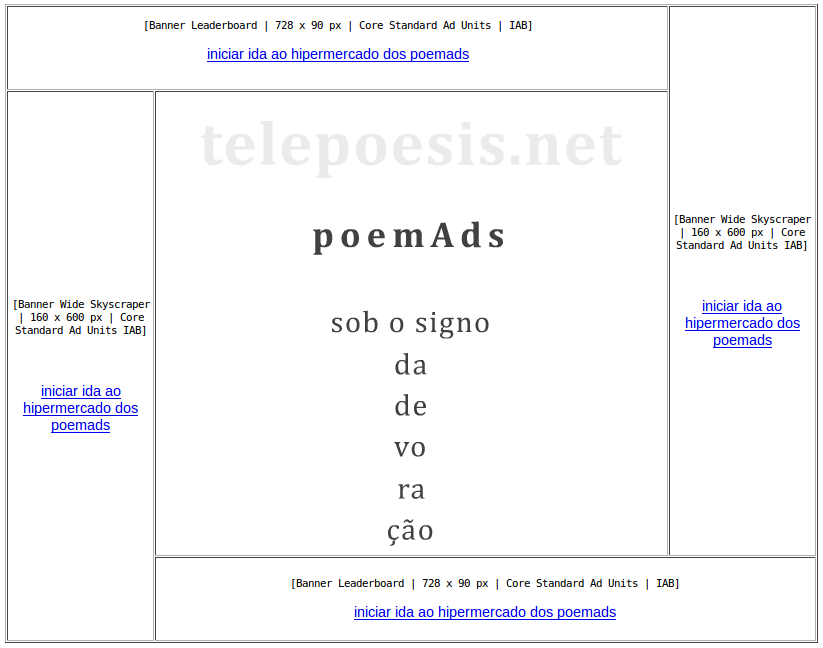

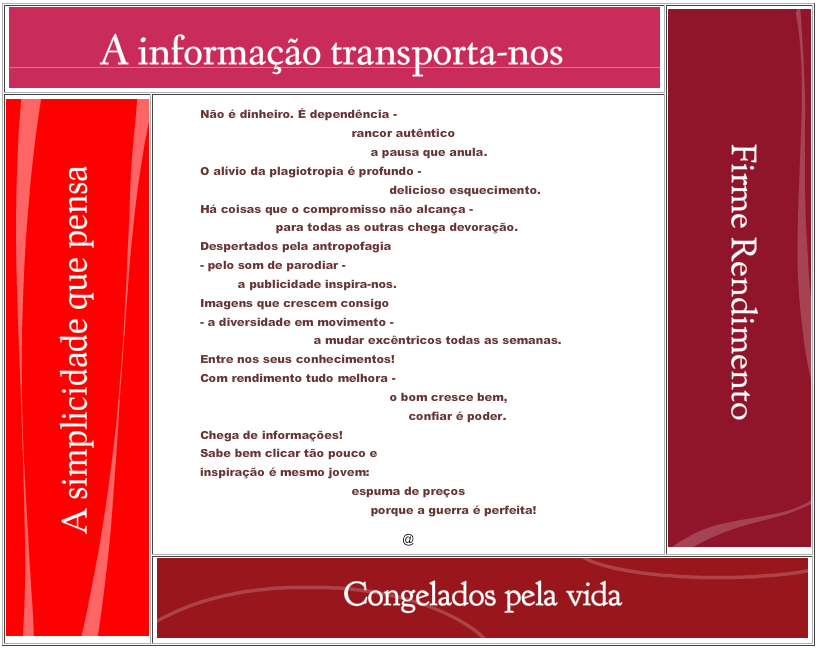

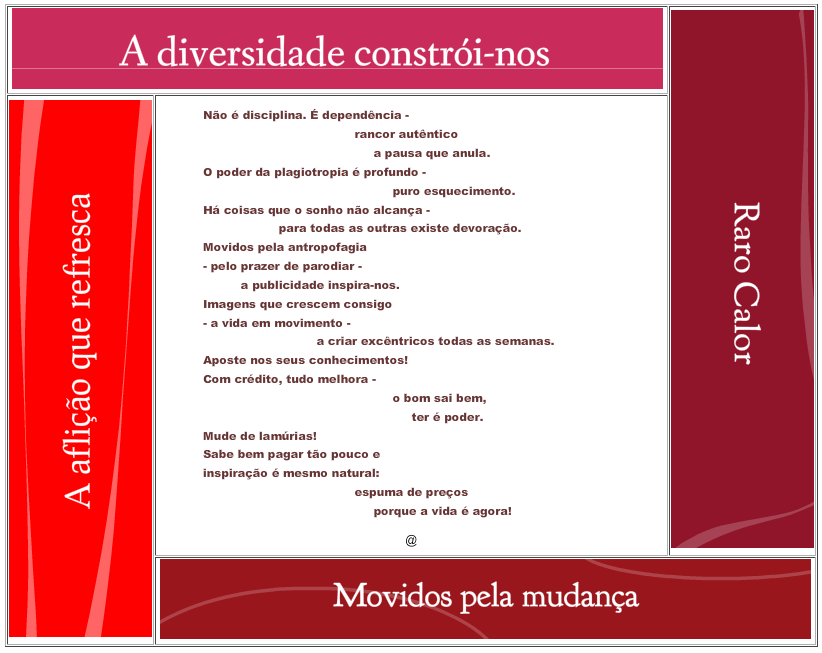

PoemAds is a generative poem that uses permutation mechanisms to promote the structural insight that Wittig mentions, in this case via the deformation of Portuguese advertising campaigns (ads for butter, yogurts, cars, credit cards, etc). PoemAds was stimulated by the Mode d’emploi du détournement, by Débord and Wolman, among other tactical media. These PoemAds were inserted into an HTML page with four (4) banners which follow the Core Standard Ad Units proposed by the IAB- Interactive Advertising Bureau. The editors of the ELMCIP Anthology, for which this work was created, wrote: “Taking on corporations and consumerism with combinatorial poetry may seem an odd enterprise but that is just what Rui Torres is attempting with PoemAds. By appropriating the slogans from various banks and other institutions, and remixing them algorithmically, PoemAds produces a text that is not singular but transitory, morphing over time. The outcome is a sort of mashup of promises taking the form of critical poetry.” (Engberg, Memmott and Prater 2012, n.p.). “Machiavellian,” Leonardo Flores has called it.

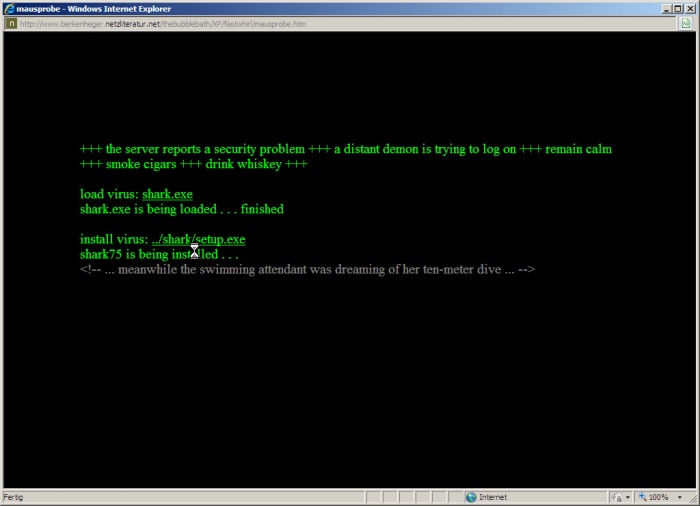

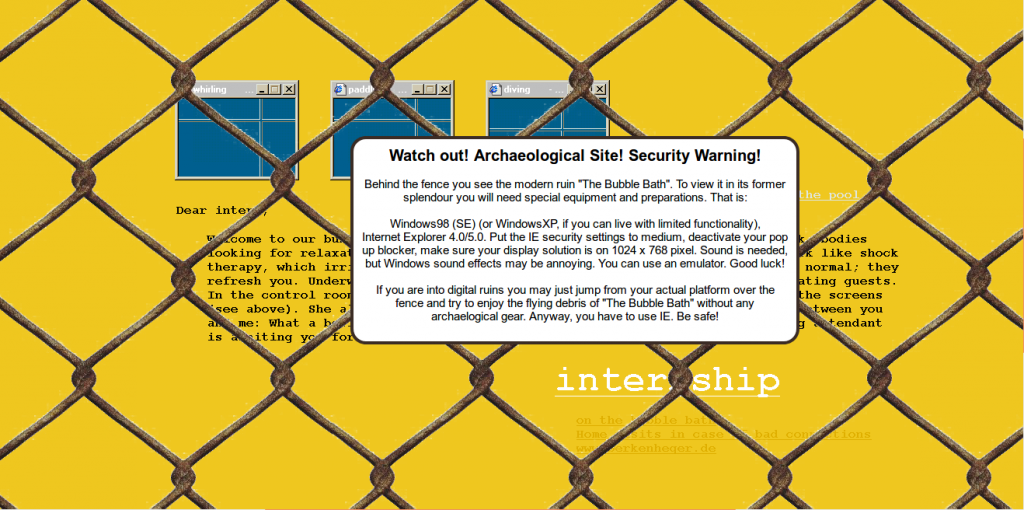

Parody with trademarks, proprietary software, and copyright laws is also staged on The Bubble Bath, by Susanne Berkenheger (2005), accessible only with a Microsoft browser. Readers using other operating systems are (were?) bestowed with a message: “The Bubble Bath is set in the eye of the occupying power called Microsoft.” More: readers are asked to reduce their protection against viruses! Because this work included ‘shark75,’ a “little fictional virus [which was] harmless [but] did what other malicious scripts and real viruses were doing,” The Bubble Bath, Berkenheger recognizes, “has become a digital ruin. As such, it is also an experiment.” (Berkenheger 2011).

Digital ruins are the result of corrupted memories, what Giselle Beiguelman has related to our contradictory experience of “a super production of memory, but also a documentary overdose.” Although we often state that the Internet never forgets, she explains, “digital culture does not allow us to remember.” (66-67). And what’s more: “We are facing a noisy ‘datascape’, which goes far beyond our screens (…). A peculiar ‘ruinology’” (78). Memory, in order to be functional, “needs to be selective, otherwise it will sink into chaos,” Jan Baetens and Van Looy remind us: “without forgetting, no remembering”(2007, n.p.). That is why the primary function of the Internet “is not that of conservation (…), but [rather] one of transformation (…)” (n.p.).

For Susanne Berkenheger, The Bubble Bath constituted ”(…) an educational training camp (…) to make the readers learn to love the fact that it is not they who drive the text; rather it is the text that is pulling them (…) by means of cheap tricks, false cursors, empty promises, invisible windows, and bad-mannered javascript codes (…)” (2011, n.p.).

These serious gibberishes may well be regarded as dadaist collages, and they share similar tactics with René Bauer and Beat Suter’s road poem AndOrDada, among many other works of e-lit that pay hommage to the dadaists.

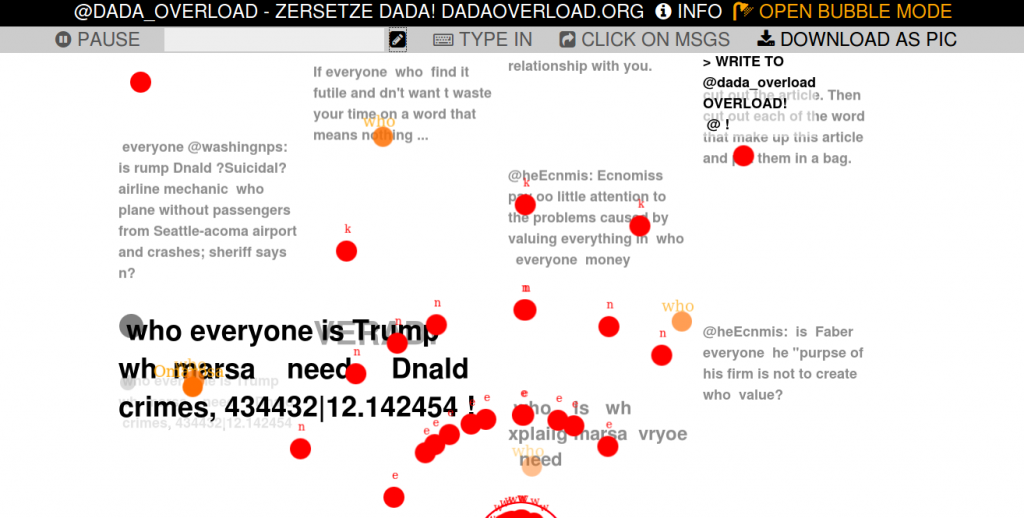

More recently, with Mirjam Weder, Bauer and Suter have programmed dadaoverload, where dada is considered as a “system cracker,” self-reflexive device that makes us “think about the poem-algorithm.” In the provided documentation, we can read:

“The world is filled with a dada overload. Today’s source material for Dada are Tweets and spam messages, ad messages and any kind of short messages. Dada used newspaper clippings, cut them down to words and randomly reassembled them. Dada was a creative process in 1916. Today, Dada is everywhere and nowhere. It is massive disintegration of language and communication. (…) Our Dada destroys tweets. It subverts, undermines, disintegrates and decomposes tweeted messages.” (2017b)

Is Dada the right affiliation of e-lit? And, if yes, is e-lit cynical, a “cynicism (…) enlightened [by] false consciousness”? Connected, like Dada, to a “dynamic of cultural liberation struggle”? An “art of a militant irony” (391), as Sloterdijk also determines? Kirschenbaum’s “seriousness of purpose” and “conceptual density” in e-lit thence connects to the social and symbolic institutionalization identified by Block in the identity of a field that is aggregated by “Internet platforms, databases, archives, collections, anthologies, exhibitions, festivals, congresses.” (2018, p. 15).18 For Block asks: “How much room is there for destabilization within the stabilizing organization of electronic literature?” (15). Sloterdijk similarly identified the ‘failure’ of Dada in its respectability: “Instead of the unrespectably glittering productions of Dadaist ‘projected’ artists of life and politicking satyrs, projectedness in its respectable variant won out.” (1987, p. 394). How can we resist stabilization and projectedness? How can we circulate textuality in an age of big data? Dada’s chaotology may well be the opposite of database structures and archival taxonomies. And yet, here we are, dealing with archives, collections, festivals, and congresses.

How can we be humorous, let’s say, with databases and archives? Archives are intended to regulate, and to archive is to rule, to govern. For Foucault, archives are available to be “institutionalized, received, used, re-used, combined together” (1972, p. 115), forming statements of existence. Archives deal with memory, and therefore they are very much connected to data.19 To archive reinforces the notion of accumulation, signaling and encompassing discourses of totality: ”(…) the idea of accumulating everything, of establishing a sort of general archive, the will to enclose in one place all times, all epochs, all forms, all tastes (…), this whole idea belongs to our modernity.” (Foucault 1986, p. 26; my italics).

Les Archives de C.B., by Christian Boltanski,20is a collection of over 2,000 photographs, letters, and other personal and professional documents that stage, as Kate Albers acknowledges, our “fascination and obsession with the total archive.” The boxes where the archives are confined, bearing no labels, imply, for Albers, that “inaccessibility is built in to their design and presentation.” (2011, p. 252). And Alber concludes that “[t]he work teases the viewer, and particularly the scholarly one: twenty-three years worth of archival material, safely ensconced in a museum’s care, but rendered inaccessible.” (252). A silent archive, or an archive of silences, demonstrating the artist’s “compulsion to attend to the problem of “saving everything"" (Albers 2011, p. 252).

Write-only memory (WOM) is the opposite of read-only memory (ROM) - a memory device which can be written but never read.21Boltanski’s archive can be interpreted as WOM, a work that smartly (and humorously) compels us to reflect on memory processes in an age of big data.

WOM, on the other hand, seems to be the opposite of Kenneth Goldsmith’s (failed?) project “Printing out the Internet,”22 precisely inspired by the Aaron Swartz’s case with Big Data. A provocation, for sure, detouring the gap, asking how it is that power can be exercised through totality, and how indeterminacy and the impermanence of networks provides an opportunity for a change of mindsets, or at least some reflection.

From archival materials rendered inaccessible to the excess of full accessibility, from silence to noise, in the case of sound artist Christian Marclay, the illegibility of representation seems to sustain White noise (1993), an installation of photographs, where readers can only see their backs.23 When we write in a digital environment, do we add, do we substitute, or do we delete the previous layers of writing?

Is The Black Book (a print on demand volume by Jean Keller, consisting of 740 pages24 that are completely printed in black on both sides) the opposite of White Noise by Marclay?

What gets to be archived? And what gets to be silenced, erased, or deleted? Graffitis, much like palimpsests, are erasures, multi-layered texts/surfaces, scraped or washed off in order for the scroll or page or wall to be reused for another document. For Gérard Genette (1982), palimpsests are metaphors for ‘second degree’ forms of literature and art. Banksy’s Graffiti Removal (also known sometimes as Power Washer),25 created in May 2008 on Leake Street, London, and painted over by August 2008, is a depiction of an ancient cave painting being cleaned by a city worker. It proves awareness about the destruction of his/her/their work. What about ourselves? Are we aware about the tenuous nature of our own works?26 That which remediates abstract numerical information into readable information or meaningful signs remains invisible as such, Laermans and Gielen (2007) have explained.

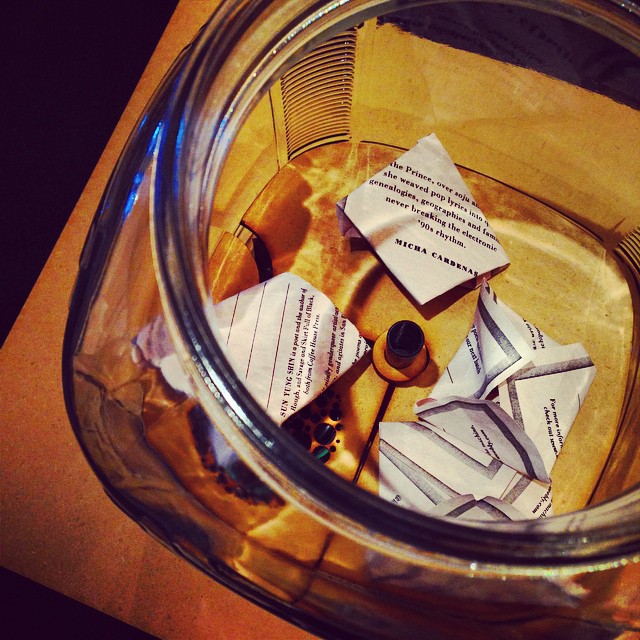

Escrita [Writing] is a poem-object by Abílio-José Santos (Santos s.d.) composed of punch cards and paper tape (used to store data and computer programs) inside a pharmaceutical jar. What is written (and what constitutes writing) here? What does this code do?

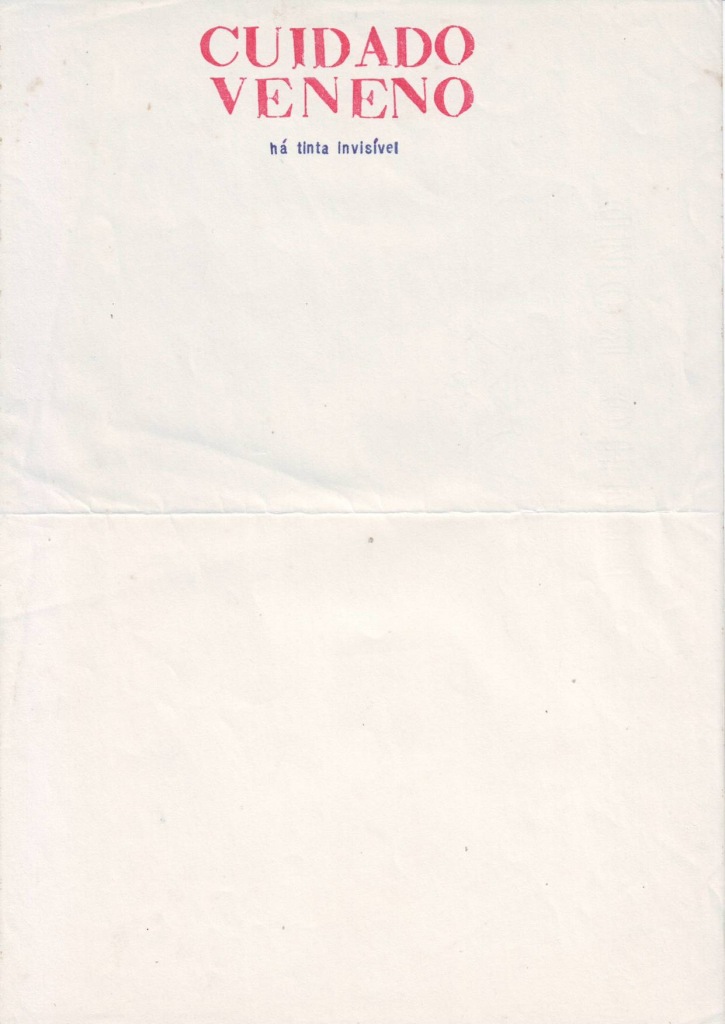

Another poignant example by Abílio-José Santos is Cuidado Veneno, 27 an empty page (is there such a thing as an empty page?) with “Careful Poison” as title, and “there’s invisible ink” as sub-title. What is read (and what constitutes reading) here? 28 What does this instruction do?

These works by Boltansky, Banksy, Marclay, and Abílio, being so different between them, and not recognizable as examples of electronic literature, nevertheless establish expressive dialogues with concepts that should be dear to those writing in, and about, digital platforms, namely illegibility and erasure. Let’s recall the Joker and his killing joke again. Let’s imagine that we acknowledge we are living in an asylum, and we decide to escape from it. What narrow gaps will we be forced to cross? What flashlights will show us the paths between these gaps?

Let us now do another exercise, trying to translate these non-electronic literature works to forms that now include some remnants of code, networking, programmability. Let us ask: how should we, how could we remediate these works?

Escrita [Writing] could perhaps be remediated (or better, recontextualized) in the Kimchi Poetry Machine, by Margaret Rhee (2014), where she uses tangible computing: when the jar is opened, “poetry audibly flows from it, and readers and listeners are immersed in the meditative experience of poetry.”

Small paper poems are inside the jar, with invitations to tweet a poem to the machine handle, and eight original feminist “kimchi twitter” poems were written for the machine by invited women and transgender poets.29 Poetry is food, feeding participation.

As for “Careful Poison,” my own Fakescripts (Torres and Ferreira 2017), code snippets from several programming languages, appropriated and adapted for the inclusion of poetry, may establish a parallel and a transcoding engagement. Programmed – but inoperable – poetry, code stuck on the wrong medium, defamiliarizing our digital condition, transforming transparent appliances into illegible devices. Indeed, a programmed – but inoperable – poetry is put to sleep in the public space of a city: printed on cushions, placed on the benches of a gallery, awaiting for the uneasy discovery of the visitor. A poetic operation, programmed to be seen only, is inscribed in a digital technology of inverted materiality (a code stuck on the wrong medium, i.e., a fakescript). A code thus falsified, integrating programming languages with syntactic coherence, semantic ambiguity, but pragmatic inefficiency: a poetic programming extracted from the mediaphere, printed in the ecosphere.

The same seems true for C.O.P.Y., by Martin Wecke (2013). We can only read if. The pages of C.O.P.Y. are unavailable for our eyes, they can not be read. However, after copying or scanning them, the book unveils the essay Copyright, Copyleft and the Creative Anti-Commons by Anna Nimus (2006). The inevitable irony remains in the fact that the text’s legibility improves with the copying process. Martin Wecke explains that Nimus’s essay “traces back the history of copyright and its underlying power relations and offers a radical conception of a cultural commons and Copyleft. The work C.O.P.Y. consists of a book developed for this text, exaggerating the idea of Open Source and its main principles of copy, modification and distribution rights by applying them to the realm of print publishing.”

Constraint is exercised through humor, and humor is a strategy to exercise our freedom acts from within closed platforms and the rules of software. Unlike with Eastman’s “irresponsible essay-writer,” performing inconsequential theory about something that evades theorization (that would be me), the sanitarium where Bernard Shaw wants to place those writing about wit and humor is not proper punishment for e-lit authors using parody, irony and humor in general. Rather, it is a sanitarium where we all already seem to be living. Wecke’s C.O.P.Y. is disturbing precisely because it hides the text from the reader’s view, forcing her to commit a mechanical (and albeit illegal) action in order to disclose it.

“OK, sit down and pay attention. We’re only going to say this once,” William Gibson declared on National Public Radio, December 9, 1992. Agrippa (A Book of the Dead),30 created with Dennis Ashbaugh in 1992, is an electronic poem (is it?) by Gibson regarding the ethereal nature of memory (Gibson et al. 1992), hence and again encompassing archives. Stored on a 3.5” floppy disk, this book/program was programmed to encrypt itself after a single use, and standard spy trope aside,31 the pages of the book were treated with photosensitive chemicals, causing the successive fading of the words and images… A “book of sand,” as with Borges’? “Careful, Poison, there’s invisible ink?,” as in Abílio’s? C.O.P.Y. me? According to Matthew Kirschenbaum, “[t]oday, the 404 File Not Found messages that Web browsing readers of Agrippa inevitably encounter … are more than just false leads; they are latent affirmations of the work’s original act of erasure that allow the text to stage anew all of its essential points about artifacts, memory, and technology.” (2005)32

These works are conscious of the processuality of writing, they have an intentional incompleteness. They escape the domain of archives, notational systems, they evade the slavery of writing. Writing appears as a mechanism of liberation of the imagination. Humor sets them free from constraint. They stand as a metaphor for Big Data and how it turns archives into “manifestation[s] of power, (…) symbol[s] of authenticity and authority” (Hui 2013), much in the same way that Google and/or Facebook struggle to keep, organize, and aggregate our private lives on records, on servers, in “the cloud.”

The Deletionist, as Amaranth Borsuk, Jesper Juul, and Nick Montfort (Borsuk et al. 2013) explain, is “a concise system for automatically producing an erasure poem from any Web page [that] systematically removes text to uncover poems.” Removing text to uncover poems through a JavaScript bookmarklet echoes other methods of erasure, in painting and literature, in applets and videogames, as the authors recognize. However, in this “game of destroying language,” the declared goal is to further “amplify, subvert, and uncover new sounds and meanings in their sources.” Is there poetry hidden in the electronic book review?

Degenerativa [Degenerative] by Eugenio Tisselli (2005) is yet another example of a web page that slowly becomes corrupted with user interaction. Each time the page is visited, one of its letters is (was?) either destroyed or replaced.

Ephemeral and self-destructive messages are an actual phenomenon of the web, a way of protecting oneself from prying eyes… Here, however, the programmed impermanence is a reflection on our latent net condition.

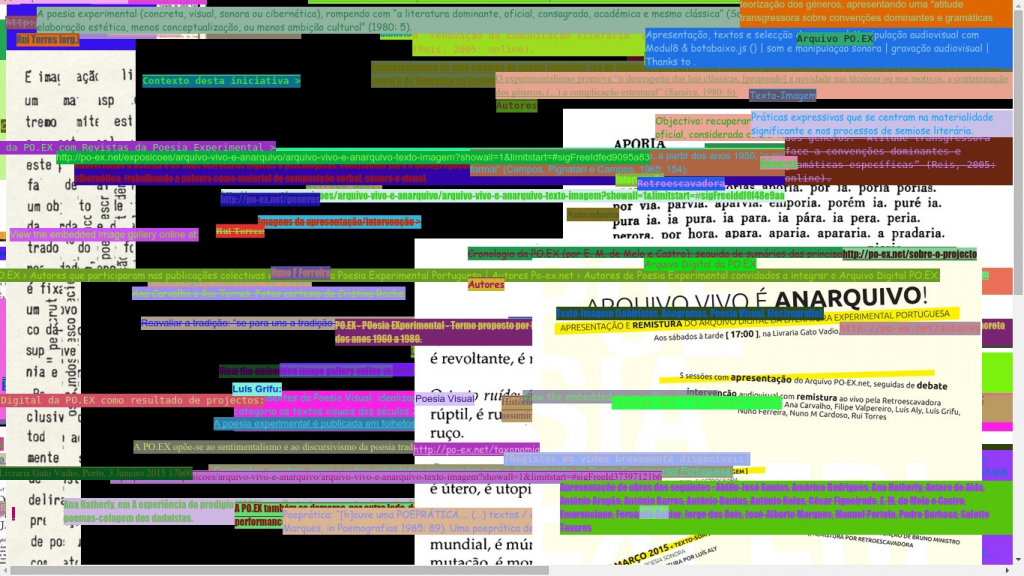

In A LIVING ARCHIVE IS AN ANARCHIVE!, organized in Porto and in Coimbra, among other remixing activities, a series of scripts were programmed by Nuno Ferreira to actually transform and destroy the po-ex.net database, allowing for live-manipulation of style and contents, distorting, inverting, and eventually deleting its pages.33

And now, working on the Electronic Book Review as well:

Nuno Ferreira’s script fademe.js [progressively evaporating ebr’s web site text content]. April 2019.

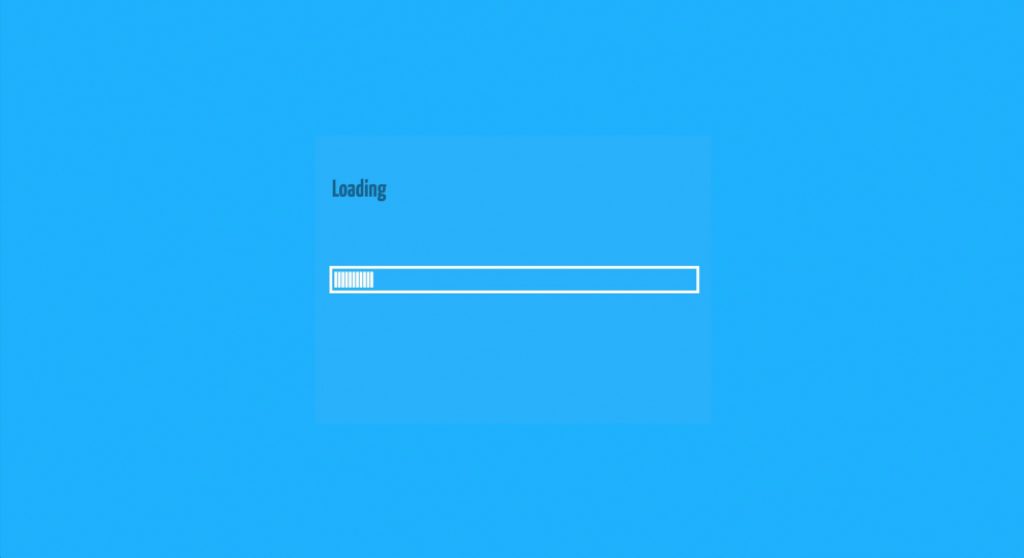

1_100 is a digital minimal poem by Bruno Ministro (2016a), based on the appropriation of the sound work “1,100” by Charles Bernstein (1969). The poem’s interface uses the blue color of the standard theme of Windows 10 operating system, “seeking to build a poetic path for profanity and détournement.” (Ministro 2016b). The user’s expectation are frustrated: we expect the “poem” to appear, so that we can read it, but all we get is an error message and a call to refresh the page. This Sisyphus-like process of having to load the loading poem all over again, as Ministro explains, acts “through latency, despair, and frustration.” (Ministro 2016b). And Ministro further asks: “Is time in the digital age a different type of time?” (2016b).

Nuno Ferreira’s script fademe.js [progressively evaporating ebr’s web site text content]. April 2019.

1_100 is a digital minimal poem by Bruno Ministro (2016a), based on the appropriation of the sound work “1,100” by Charles Bernstein (1969). The poem’s interface uses the blue color of the standard theme of Windows 10 operating system, “seeking to build a poetic path for profanity and détournement.” (Ministro 2016b). The user’s expectation are frustrated: we expect the “poem” to appear, so that we can read it, but all we get is an error message and a call to refresh the page. This Sisyphus-like process of having to load the loading poem all over again, as Ministro explains, acts “through latency, despair, and frustration.” (Ministro 2016b). And Ministro further asks: “Is time in the digital age a different type of time?” (2016b).

Again, here we are reading the reading, and thus performing a double reading (Bootz 2001). And if literary works are not the sum of their technical features, then e-lit cannot be at the service of a technocratic culture where all writing practices seem to fall under the logic of industrial management (Torres and Baldwin 2014, p. xvi). But the question remains: what type of time are we dealing with?

With Ministro’s Collected Works (2008-2016), the plot thickens: a 720 page book, with manual and traditional binding by Miss Isabel from Encadernação Progresso (Beja), employing as material data the personal history of the author’s Google activity, using the JSON files exported via My A**ctivity. As Ministro explains, privacy and freedom, vigilance and control are critically questioned in these nine years of online research. And the internet, technocapitalism and data culture are unveiled in this political engagement and commitment to the real: “The violently silent obstruction of privacy and freedom, along with the escalation of vigilance and control, are the result and process of certain hegemonic socio-political models of the new media.” (2017, n.p.)34

Liliana Vasques (2018) argues that Collected Works ” engages with the field of literature and asks questions – is this literature? What is literature? Can a work of literature involve no writing as we understand it?”. In his text “An introduction to the 21st Century’s most controversial poetry movements,” Kenneth Goldsmith seems to provide an answer: “With so much available language, does anyone really need to write more? Instead, let’s just process what exists. (…) Our immersive digital environment demands new responses from writers. What does it mean to be a poet in the Internet age?” (2009, n.p.). Goldsmith names two movements, Flarf and Conceptual Writing, identified as direct research on this subject. According to him, this new form of writing “is not bound exclusively between pages of a book; it continually morphs from printed page to web page, from gallery space to science lab, from social spaces of poetry readings to social spaces of blogs.” The work also constitutes “a poetics of flux, celebrating instability and uncertainty,” which is why Ministro’s work falls under the category of Flarf: it is “quasi-procedural and improvisatory,” “sculpted” from the Internet. And Flarf plays Dionysus, humor against constraint.

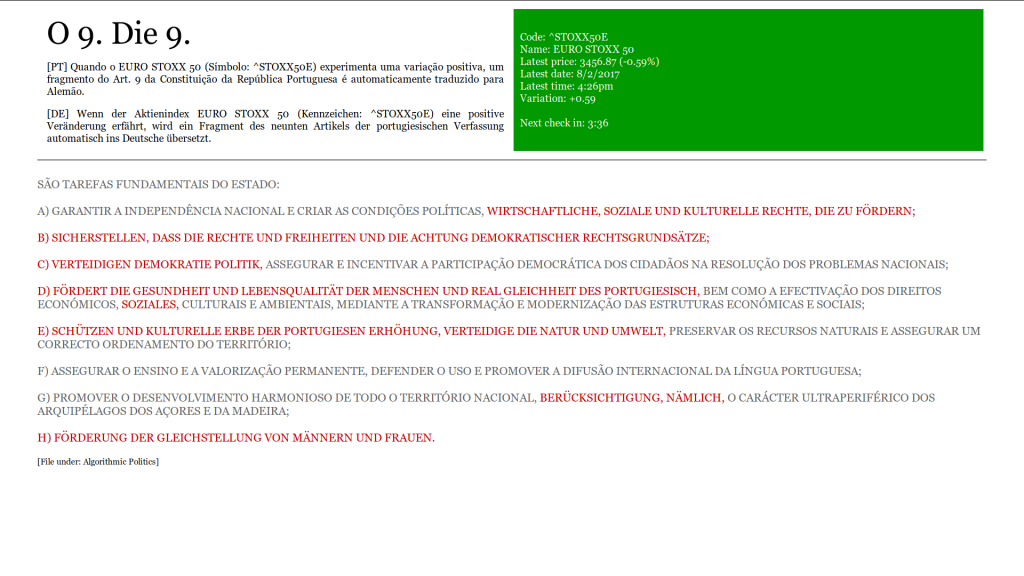

Technological self-awareness becomes political self-awareness, Wittig has argued. That is also what happens in Eugenio Tisselli’s O 9 / Die 9 [The 9th], created for one of the ELO 2017 exhibits in Porto,35 adapting (translating) El 27 / The 27th (2013), a work that criticizes the ways in which global financial capitalism spreads and devours the political autonomy of national states. In the original version, whenever the New York Stock Exchange closed with a positive percentage balance, a fragment of Article 27 of the Mexican Constitution was automatically translated into English. In the Portuguese “translation,” Article 9 of the Portuguese Constitution (with the “Fundamental Tasks of the State”) depended on the Frankfurt Stock Exchange. The text was gradually translated to German according to the financial fluctuations, obeying an automatic process of Google translator. A translation of a translation of a translation…

Ministro and Tisselli’s works seem to prove what Portela wrote concerning e-lit by Jhave, Cayley, and others: “Now that automated constrained processes are able to collect and generate endless snippets of language and thousands of poems per hour, poem-mining can still be offered to a human voice for stitching and improvisation. “Reading along with the machine” is, perhaps, the only possibility of overwriting its writing constraint.” (2017, p. 198).

In her study on “Algorithmic Translations,” Rita Raley claims that automatic translation tools “reinforce the techno-linguistic consensus, the mandate that ‘everything,’ every inscription and every speech act, be made accessible, ‘all the time,’ ‘on demand,’ wherever we are.” (2016, p. 122) – resembling Foucault’s modernist compulsion of the archive to accumulate everything. Raley proposes that because translation is a mediated, technically organized activity, “media artists working on site, within the actual terrain of translation practice—computational environments—are at the moment best positioned to explore this aspect of translational practice (…)” (122).

Google translating a paragraph of the Mexican or Portuguese Constitution becomes a performance with the machine, the algorithm intentionally substantiating the actual flaws of the system, and the work relies exactly on those imperfections to operate. Tisselli further writes: “Through total computability, numbers have become the ultimate truth: an abstract hegemony that collapses contexts and erodes human languages, imposing upon them combinatorial, connective and operational rules that render them efficient and functional, and transform them into raw data to feed economic transactions. [And] It is precisely upon this scenario where electronic literature takes place.” (2018, p. 12).

One final example, and one that may be a provocation, because it may appear to be tangential to electronic literature (not for me), is Américo Rodrigues’ performance at ELO in Porto (Rodrigues 2017). He called his performance “Vociferar contra,” (literally, To Vociferate [to shout] Against), and in many occasions his gestures holding his mouth and grasping his throat were forms of constraining his vocal improvisations. Rodrigues regularly performs by inscribing his “poems” in processes of deautomatizaton of the very reproduction mechanisms allowing sound recording. By making this reproduction device visible, by exposing the materiality of the recording, communication and amplification systems employed, and by expressively introducing the telephone, cassette recorder, megaphone or intercom, the author assembles a set of meta-mediatic sound textures, making technical reproduction itself reflexive. Ões, for Voice, French fries and Camões,36in memoriam Philadelpho Menezes, is a decisive humorous example of overcoming constraints.

conclusions ? tee write.log : sleep

In Grammalepsy, John Cayley studies digital language art both in terms of digital media and digital affordances. He argues that indexed access and archive will eventually “offer our cultures the potential to shift the central focus of its most significant and affective linguistic practice from literature to aurature.” (2018, p. x) And he further explains: “Writing and literature are overdetermined by their implicit media—archival publication in print, and practices of writing in a visuality that is constrained, typically, to literary forms or, of necessity, to literal forms.” (4)

And in our age of post-digital normativity, Joseph Tabbi debates, the literary arts are assigned to reclaim (or to make strange again) the normalization of affordances and potentials of our cultural and communicative moment (2017, p. 8). But Tabbi also polemizes: “The post-digital is no place for avant-gardes,” (7) he writes; and: “With the going mainstream of multi-modal, interconnective practice, the avant-garde is at best ‘peripheral’ (….)” (8). Although, as an artist, this was difficult to accept, after a bit of mourning, the scholar in me accepts it. But we do need to keep asking: are we ready to comply with the post-digital “domestication of a medium” (6) that we (as creators) “know how to engage from the inside, as makers [and] not as passive watchers”? Can we still “apply technical affordances in innovative ways”?

Too many questions, too few answers, I know. Allow me to finish with some balance:37

Is e-lit playing a vital role in shaping current and future literary theories and practices? Is e-lit critically engaging readers with the materiality of media, motivating aesthetic awareness about our media ecology? Is e-lit making electronic media visible, defamiliarizing our experience of interfaces? Is e-lit rendering code visible? Is e-lit (re)connecting us to the universal digital machine, translating our networked lives through awareness and criticism?

E-lit will not become a sovereign form of expression. E-lit cannot operate in complicity with the already existing media. E-lit must embody the resistance to dominant discourses. E-lit is literature, as designated. E-lit must become literature: maybe we should leave it to rest, and invent something else. Something that can help us change the world into a better place.

Albers, Kate Palmer. “It’s Not an Archive”: Christian Boltanski’s Les Archives de C. B., 1965–1988. In: Visual Resources, 27.3, 2011. p. 249-266. https://doi.org/10.1080/01973762.2011.597166

Baetens, Jan, and Jan Van Looy. “Digitising Cultural Heritage. The Role of Interpretation in Cultural Preservation.” In: Image & Narrative 17, 2007. p. 1-9. http://www.imageandnarrative.be/inarchive/digital_archive/baetens_vanlooy.htm

Barthes, Roland. Leçon. Paris: Éditions du Seuil, 1978.

Barthes, Roland. Mythologies. J. Cape, 1972.

Barthes, Roland. The Pleasure of the Text. Translated by Richard Miller. 23rd ed. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1998.

Bass, Randy. “Story and Archive in the Twenty-First Century.” In: College English, 61.6, 1999, p. 659-670.

Bauer, René, Beat Suter and Mirjam Weder. dadaoverload. 2017a. http://www.dadaoverload.org/

Bauer, René, Beat Suter and Mirjam Weder. dadaoverload.documentation. 2017b. http://www.and-or.ch/dadaoverload/

Beiguelman, Giselle. “Corrupted Memories: The Aesthetics Of Digital Ruins And The Museum Of The Unfinished.” In: Uncertain Spaces: Virtual Configurations in Contemporary Art and Museums, ed. Helena Barranha and Suzana Martins. Lisbon: UNL/Instituto de História da Arte, 2015.

Berkenheger, Susanne. Preface: The Bubble Bath. 2011. http://collection.eliterature.org/2/works/berkenheger_bubble_bath/altegurken/fastwhirl/browser.htm

Berkenheger, Susanne. The Bubble Bath. 2005. http://www.thebubblebath.de/

Block, Friedrich W. “Electronic Literature as Paratextual Construction.” In: MATLIT: Materialities of Literature, 6.1, 2018, p. 11-26. https://impactum-journals.uc.pt/matlit/article/view/5244

Block, Friedrich W. “Humor — Technology — Gender. Digital Language Art and Diabolic Poetics.” In: The Aesthetics of Net Literature: Writing, Reading and Playing in Programmable Media, ed. Peter Gendolla and Jörgen Schäfer. Transcript, 2006, p. 161-178.

Boltanski, Christian. Les archives de Christian Boltanski 1965-1988. 1989.

Bootz, Philippe. “Reading and beyond.” In: p0es1s. University of Erfurt, 2001. http://www.p0es1s.net/poetics/symposion2001/bootz.pdf

Borsuk, Amaranth, Jesper Juul and Nick Montfort. The Deletionist. 2013. http://thedeletionist.com

Bouchardon, Serge. “Towards a Tension-Based Definition of Digital Literature.” In: Journal of Creative Writing Studies, 2.1, 2017. http://scholarworks.rit.edu/jcws/vol2/iss1/6

Cayley, John. Grammalepsy. Essays on Digital Language Art. Bloomsbury Academic, 2018.

Cortázar, Julio. Rayuela. Fundacion Biblioteca Ayacuch, 2004.

Cramer, Florian. “Post-Digital Literary Studies.” In: MATLIT: Materialities of Literature, 4.1, 2016. p. 11-27. http://dx.doi.org/10.14195/2182-8830_4-1_1

Drucker, Johanna. “Amusements Électroniques.” In: MATLIT: Materialities of Literature, 6.1, 2018, p. 27-35. https://doi.org/10.14195/2182-8830_6-1_2

Eastman, Max. The Sense of Humor. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1922.

Eco, Umberto. Apocalittici e integrati: comunicazioni di massa e teorie della cultura di massa. Milano, Bompiani, 1964.

Engberg, Maria, Talan Memmott and David Prater. “About: PoemAds. Sob o signo da devoração.” In: The ELMCIP Anthology of European Electronic Literature. 2012. https://anthology.elmcip.net/works/sob-o-signo-da-devoracao.html

Ferguson, Russell. Christian Marclay. Los Angeles: UCLA Hammer Musem, 2003.

Flores, Leonardo. “sob o signo da devoração (PoemAds)” by Rui Torres. In: I Love E-Poetry. 2013. http://iloveepoetry.org/?p=72

Foucault, Michel. “Of Other Spaces.” In: Diacritics, 16, 1986. p. 22-27. [original from 1967].

Foucault, Michel. The Archaeology of Knowledge and the Discourse on Language. Trans. A. M. Sheridan Smith. New York: Pantheon Books, 1972.

Gibson, William, Dennis Ashbaugh and Kevin Begos, Jr. Agrippa (A Book of the Dead). 1992.

Goldsmith, Kenneth. “Flarf is Dionysus. Conceptual Writing is Apollo.” In: Poetry Magazine. 2009. https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poetrymagazine/articles/69328/flarf-is-dionysus-conceptual-writing-is-apollo

Goldsmith, Kenneth. Printing out the Internet. LABOR gallery, Mexico, and UbuWeb. 2013.

Hayles, N Katherine. “Translating Media: Why We Should Rethink Textuality.” In: The Yale Journal of Criticism, 16.2, 2003, p. 263-290.

Hui, Yuk. “Archivist Manifesto.” In: Mute/Lab. 2013. http://www.metamute.org/editorial/lab/archivist-manifesto

Hutcheon, Linda. “The Politics of Postmodernism: Parody and History.” In: Cultural Critique, 5, Modernity and Modernism, Postmodernity and Postmodernism, 1987, p. 179-207.

Keller, Jean. The Black Book. 2013. http://p-dpa.net/work/the-black-book/

Kirschenbaum, Matthew. “ELO and the Electric Light Orchestra: Electronic Literature Lessons from Prog Rock.” In: MATLIT: Materialities of Literature, 6.2, 2018: 27-36. DOI: 10.14195/2182-8830_6-2_2

Kirschenbaum, Matthew G. Hacking ‘Agrippa’: The Source of the Online Text. 2005. http://agrippa.english.ucsb.edu/kirschenbaum-matthew-g-hacking-agrippa-the-source-of-the-online-text

Kittler, Friedrich. “There is no Software.” In: Literature, Media, Information Systems, ed. John Johnston, Amsterdam, pp. 147-155. 1997.

Laermans, Rudi and Pascal Gielen. “The Archive of the Digital An-archive.” In: Image & Narrative, 17. 2007. p. 1-13. http://www.imageandnarrative.be/inarchive/digital_archive/laermans_gielen.htm

Lanier, Jaron. You Are Not a Gadget: Manifesto. Alfred A. Knopf, 2010.

Maduro, Daniela Côrtes. Digital Media and Textuality: From Creation to Archiving. Transcript Verlag, 2017.

Manovich, Lev. The Language of New Media. MIT Press, 2001.

Marclay, Christian. White Noise. 1998.

Ministro, Bruno. 1_100. 2016a. http://hackingthetext.net/1_100/project.html [Also published in The New River Journal, Virginia, USA, June 2016: http://www.cddc.vt.edu/journals/newriver/16Spring/index.html]

Ministro, Bruno. 1_100: Brief Summary. 2016b. http://hackingthetext.net/pdf/1_100_Presentation_BrunoMinistro_2016.pdf

Ministro, Bruno. Collected Works (2008-2016). 2017. https://projectocandonga.wordpress.com/trabalhos/collected-works/

Montfort, Nick, and Noah Wardrip-Fruin. “Acid-Free Bits: Recommendations for Long-Lasting Electronic Literature.” In: Electronic Literature Organization, 2004. http://www.eliterature.org/pad/afb.html

Moore, Alan. Batman: The Killing Joke. New York: DC Comics, 1988.

Morreall, John. “Philosophy of Humor.” In: The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2016 Edition), ed. Edward N. Zalta. 2016. https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2016/entries/humor/

Moulthrop, Stuart. ‘Just Not the Future’: Electronic Literature After the Fall. MATLIT: Materialities Of Literature, 6.3, 2018, p. 11-20. https://impactum-journals.uc.pt/matlit/article/view/5221/4730

Mukarovský, Jan. “Standard language and poetic language.” In: A Prague School reader on esthetics, literary structure, and style, ed. P. L. Garvin. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press, 1964. p. 17-30.

Nilsen, Alleen and Don Nilsen. “Literature and humor.” In: The Primer of Humor Research, ed. Victor Raskin and Willibald Ruch. Mouton de Gruyter, 2008. p. 243-280.

Portela, Manuel. “Writing Under Constraint of the Regime of Computation.” In: The Bloomsbury Handbook of Electronic Literature, ed. Joseph Tabbi. Bloomsbury Publishing, 2017. p. 181-200.

Raley, Rita. “Algorithmic Translations.” In: CR: The New Centennial Review, 16.1, 2016. p. 115–138. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/9p08q4wq

Rhee, Margaret. Kimchi Poetry Machine. 2014. http://kimchipoetrymachine.weebly.com/machine.html

Rodrigues, Américo. “Ões.” In: Escatologia. 2003. https://po-ex.net/images/stories/audio/americorodrigues/escatologia/ar_escatologia_01.mp3

Rodrigues, Américo. “Vociferar contra.” In: ELO 2017 Electronic Literature: Affiliations, Communities, Translations. TNSJ-Teatro Nacional de São João, Porto. 2017. https://po-ex.net/taxonomia/materialidades/performativas/americo-rodrigues-vociferar-contra/

Santos, Abílio-José. Escrita. s.d. https://po-ex.net/taxonomia/materialidades/tridimensionais/abilio-escrita-objecto/

Saraiva, Arnaldo. Literatura marginal izada: Novos ensaios. Porto: Árvore, 1980.

Shklovsky, Victor. “Art as Technique.” In: Russian Formalist Criticism: Four Essays, ed. Lee T. Lemon and Marion J. Reis. U of Nebraska P, 1965. [original from 1917].

Sloterdijk, Peter. Critique of Cynical Reason. Translation by Michael Eldred. The University of Minnesota Press, 1987.

Sylla, Bernhard. Roland Barthes: “A língua é fascista” – aproximações a um topos da filosofia do século XX. In: Diacrítica, 29.2, 2015, p. 135-148. https://repositorium.sdum.uminho.pt/handle/1822/47279

Tabbi, Joseph. “Introduction.” In: The Bloomsbury Handbook of Electronic Literature, ed. Joseph Tabbi. Bloomsbury Publishing, 2017.

Tabbi, Joseph. “Preface: Acid-Free Bits and the ELO PAD Project.” In: Electronic Literature Organization, 2004. https://eliterature.org/pad/afb.html

Tisselli, Eugenio. Degenerativa. 2005. http://www.motorhueso.net/degenerativa/

Tisselli, Eugenio. O 9 / Die 9. 2017. http://www.motorhueso.net/o9/

Tisselli, Eugenio. “The Heaviness of Light.” In: MATLIT: Materialities of Literature, 6.2, 2018. p. 11-25. http://impactum-journals.uc.pt/matlit/article/view/5379

Torres, Rui and Nuno F. Ferreira. Fakescripts [for Kassel]. 2017. http://p-dpa.net/work/fakescripts/

Torres, Rui and Sandy Baldwin. “Introduction.” In: PO.EX: Essays from Portugal on Cyberliterature and Intermedia by Pedro Barbosa, Ana Hatherly, and E. M. de Melo e Castro, ed. Rui Torres & Sandy Baldwin. Computing Literature series, Center for Literary Computing. 2014. p. xiii-xxiii. https://www.po-ex.net/pdfs/torresbaldwin_intro.pdf

Torres, Rui. “Curating Digital Archives: Interoperability and Appropriation @ PO-EX.NET.” In: De poesia. Arxius, poètiques i recepcions, ed. Marc Audí, Glòria Bordons, Lis Costa, Eva Figueras Ferrer, Mar Redondo-Arolas. Barcelona: Universitat Barcelona, 2017. p. 311-326.

Torres, Rui. PoemAds. “Sob o signo da devoração.” In: The ELMCIP Anthology of European Electronic Literature, ed. Maria Engberg, Talan Memmott and David Prater. 2012. https://anthology.elmcip.net/works/sob-o-signo-da-devoracao/index.html

Vasques, Liliana. “Review of Collected Works (2008-2016).” In: Electronic Literature Directory. 2018. http://directory.eliterature.org/individual-work/4951

Wecke, Martin. C.O.P.Y. 2013. https://martinwecke.de/projects/c-o-p-y/

Wittig, Rob. “Literature and Netprov in Social Media.” In: The Bloomsbury Handbook of Electronic Literature, ed. Joseph Tabbi. Bloomsbury Publishing, 2017. p. 113-132.

Žižek, Slavoj. Less Than Nothing: Hegel and Shadow of Dialectical Materialism. Verso, 2012.

Žižek, Slavoj. The Sublime Object of Ideology. London; New York: Verso, 1989.

Footnotes

-

E-lit = electronic literature. ↩

-

http://www.metrolyrics.com/i-bet-you-they-wont-play-this-song-on-the-radio-lyrics-monty-python.html ↩

-

Borrowing from Sloterdijk, Slavoj Žižek explains: “Kynicism represents the popular, plebeian rejection of the official culture by means of irony and sarcasm: the classical kynical procedure is to confront the pathetic phrases of the ruling official ideology—its solemn, grave tonality—with everyday banality and to hold them up to ridicule, thus exposing behind the sublime noblesse of the ideological phrases the egotistical interests, the violence, the brutal claims to power.” (1989, p. 29). On the contrary, “Cynical reason is no longer naïve, but is a paradox of an enlightened false consciousness: one knows the falsehood very well, one is well aware of a particular interest hidden behind an ideological universality, but still one does not renounce it.” (29). ↩

-

As Alleen and Don Nilsen explain, in The Signifying Monkey (Oxford UP, 1988), Henry Louis Gates, Jr. also contends that slaves, for being denied the use of normal and private communication, developed double-entendre Trickster signifiers: “The humor comes from the realization that simultaneous messages are being communicated and that the authority figures (usually whites) understand only one message while the other participants comprehend both.” (2008, p. 258). ↩

-

Regina Barreca argued against the notion that humor is mostly masculine. One of her arguments was precisely that feminine humor has emerged “as a tool for survival in the social and professional jungles,” working as a “weapon against the absurdities of injustice.” (Barreca apud Nilsen and Nilsen 2008, p. 259). ↩

-

Procrustes (Προκρούστης Prokroustes) or “the stretcher [who hammers out the metal]”, also known as Prokoptas or Damastes (Δαμαστής, “subduer”). https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Procrustes ↩

-

Another interesting mytheme of digital cultures is Proteus, who possesses the gift of metamorphosis, allowing him to convert in whatever his desire was: being versatile and mutable, he is liquid enough to represent our time. Hence perhaps the X-Men character Mystique, the blue female mutant, playing such a crucial role in the Marvel’s Comics and films ecology, being able to transform herself into any sort of person. Daniela Maduro (2017) adopted the concept Shapeshifting Texts in order to understand contemporary (and digital) textuality. ↩

-

Slavoj Žižek draws upon this rogue smith as a metaphor to criticize the poetic form, advocating that: “The most elementary form of torturing one’s language is called poetry—think of what a complex form like a sonnet does to language: it forces the free flow of speech into a Procrustean bed of fixed forms of rhythm and rhyme.”(2012, p. 871). I wonder if Žižek included a tradition of sonnets whose form was cannibalized throughout the history of experimental language art… To name just a few: Soneto soma 14x by Melo e Castro – poetry as math! (https://po-ex.net/images/stories/leituras/emmc\_sonetosoma14x/emmc\_sonetosoma14x\_antologiadapoesiaconcretaemportugal\_1963\_p068.jpg); Soneto ecológico by Fernando Aguiar – poetry as living organism! (https://po-ex.net/taxonomia/materialidades/tridimensionais/fernando-aguiar-soneto-ecologico/); Cent mille milliards de poèmes by Raymond Queneau – poetry as mechanism! (https://textualites.files.wordpress.com/2015/03/extrait1.jpg); Jason Nelson’s The Poetry Cube from the Series Eleven or Five – poetry as collaborative and performative event! (http://www.secrettechnology.com/poem_cube/poem_cube.html) ↩

-

An interesting example, among many possible others, of this “algorithmic character that can be compared with the compositional tactics used in computational work” is Taper, a digital literary magazine that established, for its first issue, a constraint: HTML poems no more than 1kb, 1024 ASCII characters. And Taper #2 further explored the literary traditions of the OuLiPo with the restrictions of computing systems, calling for poems with a 2KB or 2048 byte constraint. Taper is part of Nick Montfort’s Bad Quarto project, a “very small press publishing experimental and poetic work.” https://taper.badquar.to/ ↩

-

Language is a system of pure values, made possible by an economy of possibilities: paradigmatic (associative) and syntagmatic (combinatory) relationships. Electronic poetry, we all acknowledge, is much indebted to this form of dealing with constraint(s), because the relation between declared (manifested) and implied (virtual) allows for permutation, in combinatory but also in database driven aesthetics, in cybertext as in hypertext. ↩

-

The structured work (langue) is also there for freedom acts (parole). ↩

-

Original text by Sylla, translated and adapted by myself: “Não havendo um exterior à linguagem num espaço fora ou além da linguagem, cria-se então este além no interior da própria linguagem, precisamente pela estratégia da criação de não-lugares, u-topoi, i.e. lugares não ou dificilmente detectáveis.” (Sylla 2015, p. 6). ↩

-

Why walk the easy path? As stated by John Cage, in Diary: Audience 1966: “Are we an audience for computer art? The answer’s not No; it’s Yes. What we need is a computer that isn’t labor-saving but which increases the work for us to do (…)” (50). ↩

-

Tabbi also addresses the normalization of affordances and potentials in a perspective that is connected to the Russian formalists in his “Introduction” to The Bloomsbury Handbook of Electronic Literature (2017). I will return to this. ↩

-

Once upon a summer night, while enjoying the Canadian sunset with Jason Nelson, and whilst dialoguing about the end of our Flash-based works and what to do in order to reprogram (resurrect) them, he declared: “Let them die! Why don’t we just let them die?”. That really hurt me, I must admit!, but I have to agree with him. In recent email conversations, Jason confirmed: “I am fine with old works plunging to their death in a fiery hardware crash. It is inevitable that the works we make will die. This might happen through software, hardware changes.” ↩

-

Stuart Moulthrop (2018) questioned: “Do we want to have anything more to do with the Internet?”. And he replies to his own question, saying that “[m]aybe we have had enough.” According to Moulthrop: “Here is an outrageous claim: various forms of software culture circa 1975- 2000 (…) introduced discursive practices that now lie at the heart of our crisis. (…) These things have changed the world. (…) We broke (the news of) the Internet. Now we own it. (…) Yet anyone who works with data, code, and immersive media must feel a deep unease about the uses to which these technologies increasingly are turned.” (2018, p. 13-14). ↩

-

We could also argue (echoing Espen Aarseth’s ELO2015 keynote in Bergen, Norway) that there is no digital or electronic literature, just simply literature. The computational layer has influenced culture inasmuch as the cultural layer influenced the computational. As Manovich (2001) would argue with his transcoding principle, they are now being composited together. ↩

-

These essays from the Porto Conference of the Electronic Literature Organization by Block and Kirshenbaum were published in MATLIT and will appear later this year (2019) in Post-Digital: Dialogues and Debates From electronic book review (Bloomsbury Press). ↩

-

The analysis of Boltanski, Goldsmith and Marclay’s works, framed by Foucault’s theory, was previously published in an article that I have written (Torres 2017). ↩

-

More information about this work, including a photograph by Philippe Migeat, as well as documentation, can be found at the Centre Pompidou’s website: https://www.centrepompidou.fr/cpv/resource/c4rrdBq/ryjRG8r ↩

-

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Write-only_memory_(engineering) ↩

-

A blog documenting this crowdsourced project can be accessed via the Internet Archive’s Way Back Machine at https://web.archive.org/web/20151007104113/http://printingtheinternet.tumblr.com/ ↩

-

See Laura Manney’s dialogue with Marclay’s work here: https://lauramanney.com/tag/christian-marclay-white-noise/. Other examples from Marclay’s works dealing with “silence” and synesthesia could be included here. His “Tape Fall” (1989) or “The Beatles” (1989) are stimulating examples of works that are conceived to be hidden from the viewer/listener. In “Tape Fall,” resulting from an installation, a glass bottle with magnetic tape sounds of water falling inside was produced; in the second case, the complete works by The Beatles were crocheted (or weaved, to use the etimology of text) onto a pillowcase. In these cases, the question would be: how do we/can we listen? How do we/can we hear? For an overview of Marclay’s works see the catalog of the exhibition “Christian Marclay” organized by Russell Ferguson at the UCLA Hammer Museum (Ferguson 2003). ↩

-

From the author’s statement: “the price of a book is not calculated according to the amount of ink used in its production. For example, a Lulu book of blank pages costs an artist as much to produce as a book filled with text or large photographs. Furthermore, as the number of pages increases, the price of each page decreases.” (Keller 2013). ↩

-

A photograph of the work is available here: http://www.bradshawfoundation.com/banksy/ ↩

-

Interestingly, “Works by Banksy that have been damaged or destroyed” is the title of a Wikipedia page with a list of “damaged or destroyed works” created by Banksy: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Works_by_Banksy_that_have_been_damaged_or_destroyed ↩

-

https://po-ex.net/images/stories/abilio/dispersos/cuidado/abilio-josesantos_cuidado%20veneno.jpg. ↩

-

The works of César Figueiredo (https://po-ex.net/tag/cesar-figueiredo/) often deal with the usage of shredded books places in boxes or plastic bags. In dialogue with Abílio, whom he knew and worked with, his poetics of illegibility and inaccessibility seems to constitute an(other) example of an aesthetic antecedent of electronic literature. See, for example, “Der AV 01 frißt und schweigt” (1993), available at https://po-ex.net/taxonomia/materialidades/tridimensionais/cesar-figueiredo-der-av-01-frisst-und-schweigt/. ↩

-

In her description of the work, Rhee (2014) writes: “As a response to ‘bookless’ libraries, The Kimchi Poetry Machine reimagines how tangible computing can be utilized for a feminist participatory engagement with poetry. This installation work exists at the intersection of poetry, food, and machines. The fermentation process used to create and store kimchi in the jar becomes a metaphor for the creative and computational processes that produce the work. Opening a jar to activate the work creates parallels with the opening of a book or executing a file for a reader to consume.” ↩

-

The Agrippa Files, created by the UC Santa Barbara’s “Transcriptions Project,” is a scholarly site that presents pages from the book, archive of materials, an emulation of the poem, analysis of the code, a vídeo, essays , annotated bibliographies, etc.: http://agrippa.english.ucsb.edu/ ↩

-

“This tape will self-destruct in five seconds. Good luck, Jim,” we can hear in Mission: Impossible… ↩

-

Agrippa remains a fundamental case study for anyone interested in studying aspects of erasure and memory, emulation and obsolescence. Matthew Kirschenbaum’s Mechanisms: New Media and the Forensic Imagination (MIT Press, 2007) is a significant contribution to that discussion. ↩

-

https://po-ex.net/exposicoes/arquivo-vivo-e-anarquivo/nuno-ferreira-botabaixo-fademe-fuzzyme-scripts-para-manipulacao-do-po-ex-net/4/ ↩

-

My translation of Portuguese description by Ministro published here: https://po-ex.net/taxonomia/materialidades/planograficas/bruno-ministro-collected-works/ ↩

-

Translations - Translating, Transducing, Transcoding at Mosteiro de São Bento da Vitória, curated by Ana Marques and Diogo Marques. ↩

-

https://po-ex.net/images/stories/audio/americorodrigues/escatologia/ar_escatologia_01.mp3 ↩

-

The “manifesto” that follows contains excerpts from my reply to “Complicity and Resistance: a Critical Mass Interview”, by David Ciccoricco, to be included in “Poetics, Polemics,” a section of a forthcoming book edited by Joe Tabbi. My thanks to Joe and David for granting me permission to re-use this text in another context. ↩

Cite this article

Torres, Rui. "" Electronic Book Review, 5 May 2019, https://doi.org/10.7273/ak6v-pv72