Letters That Matter: The Electronic Literature Collection Volume 1

John Zuern considers the significance of the first volume of ELO's Electronic Literature Collection for the future of electronic arts.

John Zuern considers the significance of the first volume of ELO’s Electronic Literature Collection for the future of electronic arts.

“What are letters?”⏴Marginnote gloss1⏴Our treatment of words and letters as material objects is of particular concern to Walter Benn Michaels in The Shape of the Signifier, reviewed here by Lori Emerson.

— Lori Emerson (Oct 2007) ↩

Nell, the young heroine of Neal Stephenson’s The Diamond Age, poses this question to her older brother Harv in response to his explanation that the letters “MC” are an abbreviation for “Matter Compiler,” a household device that in the novel’s nanotech-saturated world assembles consumer goods on demand from their molecular components. The children are examining the MC’s interface, made up primarily of a scrollable menu of animated icons, “mediaglyphics,” that represent the available products. It is only in terms of these universal pictograms that Harv, himself barely able to read, can make the concept of “letters” make sense: “Kinda like mediaglyphics,” he answers, “except they’re all black, and they’re tiny, they don’t move, they’re old and boring and really hard to read. But you can use ‘em to make short words for long words” (46). In a civilization in which images, in particular moving images, have superceded alphabetic text as the principal means of communicating ideas, “letters” are pushed into an ancillary role, good for little more than captions, trademarks, and abbreviations.

The scene is something of a set-up, for one of the main plot lines of The Diamond Age follows Nell’s burgeoning literacy, and to a large extent her co-protagonist in the novel is a book, the “young lady’s illustrated primer” that rescues Nell (and, ultimately, legions of abandoned Chinese girls) from the squalor and danger of an unlettered, underclass existence. Far from old and boring and really hard to read, however, Nell’s interactive primer is a supremely user-friendly, voice-activated, image-rich, interactive text that keys its lessons to Nell’s abilities and circumstances with uncanny precision. Though some might understand The Diamond Age as a critique of runaway technological development and a conservative plea to get back to the fundamentals (“If only our young people would read more!”), more than a decade after its publication in 1995 the novel’s vision of a powerful confluence of literate practices and emergent technologies continues to inspire optimism in all of us who believe that reading still matters and that our technologies for the display and transformation of written texts are allowing us to develop forms of digital literature that will matter as much, though perhaps in different ways and for different audiences, as have the dominant print-based forms of literary expression whose cultural prestige may now be on the wane. Indeed, Stephenson’s novel can be read as a cautionary hymn to “letters,” not only as graphical symbols but as a whole domain of artifacts geared toward delight, instruction, and ethical-political mobilization. In Nell’s primer, cutting-edge technology augments and accelerates the power of the written word, and Stephenson’s novel leaves us with the hope that MC might not, after all, turn out to be the TV’s inevitable successor as the cornerstone of human culture.⏴Marginnote gloss2⏴Adalaide Morris more specifically considers the ‘tutor texts’ in the Electronic Literature Collection and, in doing so, articulates a poetics for the emerging field of e-lit. Chris Funkhouser, on the other hand, reads the Electronic Literature Collection Vol. 1 as an effective reflection of literary expression and areas of textual exploration in digital form.

— Lori Emerson (Oct 2007) ↩

Whether or not “ELC” becomes, as I think it should, the universally recognized acronym for our most comprehensive, most painstakingly documented, and most intelligently designed resource for primary texts in electronic literature, the first volume of the Electronic Literature Organization’s Electronic Literature Collection, edited by Katherine Hayles, Nick Monfort, Scott Rettberg, and Stephanie Strickland, will stand a monument to responsible (and admirably non-commercial) matter compilation. Released on the Web and as a freely distributed CD-ROM in October 2006, ELC 1 gathers together 60 computer-based literary projects from over 45 authors or teams of collaborators. The selection spans a little more than a decade: the earliest entries are Alan Sondheim’s Internet Text, the first installments of which appeared in 1994, and Michael Joyce’s Twelve Blue, published in 1996; among the most recent works are Sharif Ezzat’s Like Stars in a Clear Night Sky, Mary Flanagan’s [theHouse], Richard Holeton’s Frequently Asked Questions about ‘Hypertext,’ and Marko Niemi’s Stud Poetry, all of which appeared in 2006.

Even this small sample of six works from both ends of ELC 1’s historical spectrum - one tenth of the volume’s contents - testifies to the diversity of genres, interface modes, programming environments, and human languages represented in the collection. Sondheim’s project invites readers to browse text files the author has published on mailing lists since 1994. Twelve Blue represents Joyce’s attempt to adapt his pioneering approach to composing hypertext fiction in Eastgate’s StorySpace software to the constraints of mid-1990s HTML. Ezzat uses Flash to layer audio files in Arabic and short fictions written in English by way of a strikingly simple clickable interface. Flanagan uses Processing to create a navigable architectural environment within which texts and geometric shapes unfold an autobiographical narrative. Holeton warps the familiar Web FAQ list into a wry meditation on hypertext authorship, identity, sexuality, and U.S. politics. Niemi’s Stud Poetry employs JavaScript to stage a poker game in which the values of cards are words and the reader plays (with the welcome option to vary the speed of the game) against major French poets. Virtually any random sampling of ELC 1’s offerings will reveal a similar cross-section of styles, themes, and technologies.⏴Marginnote gloss3⏴ebr has long been an advocate of critical and creative pieces on/of eletronic literature - its ever-growing collection of writing includes work by the editors of the ELC (Strickland, Hayles, Montfort, and Rettberg) as well as work by contributors to the ELC (Sondheim, Memmott, and Stefans).

— Lori Emerson (Oct 2007) ↩

One of the greatest strengths of this first volume is its generously broad and refreshingly international interpretation of what constitutes “electronic literature.” Rather than defaulting to a “Web portal” model, the editors have done an impressive job of leveraging the format of the Collection to allow the inclusion of works that were not originally Web-based, in particular a judicious selection of interactive fictions such as John Ingold’s All Roads, Aaron A. Reed’s Whom the Telling Changed, and Emily Short’s Galatea, for which they provide downloadable z-interpreters. ELC 1 also includes materials in languages other than English, notably representative works of the French ALAMO and LAIRE poets who where among the first to experiment with computer-generated texts, among them Philippe Bootz and Marcel Frémiot’s The Set of U and Patrick-Henri Burgaud’s Jean-Pierre Balpe ou Les Lettres Dérangée. Loss Pequeño Glazier’s Spanish-English White-Faced Bromeliads on 20 Hectares represents another part of the world and another set of literary traditions. The editors’ commitment to diversity and their finely tuned historical sensibilities make ELC 1 a boon to experts and novices alike. No one who spends any time perusing this collection can come away with the impression that electronic literature is synonymous with hypertext, or with combinatorial experiments, or with kinetic typography, or with computer games, though even the most casual browser may well encounter in a single reading session all of these dimensions of the field, as individual examples as well as in various combinations in the many “hybrid” works featured in the collection.

Traversing the ELC

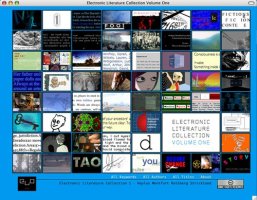

Serendipitously rewarding as it may be, casual browsing is not the only and probably not the optimal way to engage with ELC 1. Exemplifying the powerful fusion of a simple, lucid hypertext architecture and a consistent, understated editorial style, its interface design elegantly facilitates a range of more consciously directed approaches to the material. The collection clearly draws on the strengths of the ELO long-established Electronic Literature Directory The ELO Electronic Literature Directory, supervised by Robert Kendall and programmed by Nick Traenker, can be accessed at http://directory.eliterature.org/index.php. but with the advantage of a more approachable scale (60 works versus the more than 2300 currently in the Directory) and consequently a more intuitive interface. Dominating the site’s home page is a visually appealing gallery of thumbnail screenshots from each of the selections, arranged in a grid according to the arbitrary diplomacy of alphabetical order by the primary author’s last name (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. The home page of the Electronic Literature Collection, Volume 1.

These rollover images allow readers to identify and then navigate to each work in the collection. Readers can also consult tables of contents arranged by author, by title, and by a provocatively jumbled assortment of “keywords.” All paths to the individual entries, however, initially bring readers to the eminently useful page of notes that accompanies each selection, offering concise descriptions of the work by both the ELC editors and the original author(s), a publication history, helpful instructions for reading (and occasional warnings about works that crashed browsers in user testing), and a list of the ELC keywords associated with the text. These prefatory notes play a central role in establishing the coherence of the collection, orienting readers to the ELC’s overarching organizational structure without hampering their access to the texts they want to read or, as sometimes happens with more heavy-handed editors, dictating how they ought to read them.

Many of ELC 1’s keywords appear to have been derived not so much from deductive (and reductive, predetermined) categories as from inductive (and provisional, emergent) observations of the distinctive qualities of individual works. While the collection’s many genre- and technique-based keywords point critically inclined readers toward the “more pragmatic questions of taxonomy and epistemology” (that ELC editor Scott Rettberg upholds in a 2002 riposte here on EBR), the not-quite-Borgesian range and diversity of its other organizational categories mitigate the seductive will-to-typology that has at times constricted critical discourse on electronic literature, hypertext in particular. While keywords such as “Flash,” “Java,” “Inform,” and “Quicktime” allow readers to group together pieces composed using specific technologies and to conduct intra- and inter-format comparisons, “Memoir,” “Poetry,” “Fiction,” and other genre-centered categories suggest other sets and other comparative strategies. Keywords pointing to social and linguistic factors, for example “Women Authors,” “Authors outside North America,” and “Multilingual or Non-English,” contribute an important counterweight to those emphasizing genre and form. The editors have paid careful attention to how they assign keywords to selections, maximizing their utility as fairly fine-grained identifiers while maintaining their categorical integrity.

Some of the available keywords, for example “CAVE,” “hacktivist,” “installation,” “locative,” and “database” are not associated with any of the titles included in this first volume, though the uncharacteristically baggy category “critical/political/philosophical,” which includes works such as Melinda Rackham and Damien Everett’s carrier (becoming symborg) and Noah Wardrip-Fruin, David Durand, Brion Moss, and Elaine Froehlich’s outstanding Regime Change, does appropriately cross-index “hacktivist.” We can hope that these “empty” keywords serve as placeholders for works that will be included in future ELC volumes. In a less fully conceived project they would have been a distracting inconsistency, but here they speak to the inclusive, forward-looking spirit propelling the ELC’s project. If upcoming volumes aim to feature works produced for CAVE and installation environments, for example the projects Screen and Talking Cure led by Noah Wardrip-Fruin, the ELC will have to develop a robust means of documentation, a departure from this inaugural volume, which seems admirably dedicated to delivering “the thing itself.” Judging by the care the present editors have taken to describe and contextualize each piece in ELC 1, it seems clear future editorial collectives, following their lead, will be up to this task.⏴Marginnote gloss4⏴Even though the collection lacks a formal timeline, Chris Funkhouser praises the possibility of tracing the evolution of digital textuality within the past two decades in his own review of ELC 1, also available on ebr.

— Stefanie Boese (Oct 2007) ↩

Though it is not unusual for literary anthologies to be assembled by a team of editors, it seems highly appropriate that the ELC has been guided by a group of four prominent members of the electronic literature community with complementary areas of expertise. Exploring the ELC by way of the list of authors quite strikingly reveals the degree to which the creation of electronic literature has itself depended upon community and collaboration. The Flash piece Cruising represents the enormously productive partnership of Ingrid Ankerson and Megan Sapnar, whose online journal Poems that Go provided a forum for work in kinetic literature from 2000 until 2004. The collaboration of Judd Morrissey and Lori Talley has produced, in addition to The Jew’s Daughter, remarkable later works such as My Name is Captain, Captain. (published by Eastgate Systems in 2001) and the installation/performance piece The Error Engine. M D. Coverley, who has collaborated with many writers on electronic projects, including ELC editor Stephanie Strickland, appears here as the author of Accounts of the Glass Sky as well as co-author, with Rainer Strasser, of the lovely ii - in the white darkness: about [the fragility of] memory. Rainer Strasser appears as co-author, with Alan Sondheim, of Dawn. Kate Pullinger, whose collaboration with the artist-designer babel Inanimate Alice: Episode 1: China is included here, has also worked with Talan Memmot. The selection of generative poetry by Australian writer geniwaite borrows text from Brian Kim Stefans, whose celebrated Dreamlife of Letters is based on a text by critic Rachel Blau DuPlessis… In short, ELC 1 gives us a glimpse of the dense web of interpersonal relationships, borrowings, tributes, and lampoons that make up the central nervous system of any literary movement.

In ELC 1, entries cannot be sorted by date of publication, a deficit that for the time being poses no serious problem, as the dates are prominently included in all listings and in the explanatory notes, and historically inclined readers can easily assemble their own timelines. As the ELC expands to include more volumes, however, I think many readers would welcome the opportunity to sort entries across volumes into some kind of timeline structure. A temporal overview of the material would allow for a range of interrelated historical perspectives.

Among the many threads of historical research ELC 1 suggestively spins out, the opportunity to trace the afterlives of classical literary hypertext through what Hayles has called “second-generation electronic literature” is especially inviting. This first volume is bright with the hypertext stars of the early 1990s: Michael Joyce, Stuart Moulthrop, Shelley Jackson, and Deena Larson are all represented, though in all cases in the form of more recent (and more Web-tolerant and often image-laden) examples of their writing. In his well-known 1999 eulogy for the “golden age of hypertext,” Robert Coover expresses concern about the potential of the highly visual, animated formats for electronic literature that have emerged since the mid-1990s “to suck the substance out of a work of lettered art, reduce it to surface spectacle.” The intelligence of the recent work ELC 1 groups under “Animation/Kinetic” and “Visual Poetry or Narrative,” such as Coverley’s Accounts of the Glass Sky and Deena Larsen and Matt Hanson’s Carving in Possibilities, seems to suggest not only that these concerns are unfounded, but that authors are incorporating elements of the classical hypertext tradition into the concrete forms and conceptual structures of contemporary electronic writing. Nick Monfort may well be correct in his assessment that “the hypertext corpus has been produced; if it is to be resurrected, it will only be as part of a patchwork that includes other types of literary machines” (“Cybertext”), but even in patchwork, the aesthetics of hypertext pervade contemporary electronic literature. A great many of the works collected in ELC 1, and indeed the format of the collection itself, indicates the extent to which the tendrils of golden-age hypertext continue to cling to the structures of very different literary edifices, perhaps including its own mausoleum.

Like the history of hypertext, the history of electronic literature as a whole is brief but hardly shallow; the 10-odd years and 60 works represented by ELC 1 amply indicate the aesthetic and technical complexity the field’s past. As it grows older, an explicitly historical orientation to collecting its exemplars will be increasingly crucial. In this regard, Chris Funkhouser’s Prehistoric Digital Poetry: An Archaeology of Forms 1959-1995 provides a welcome contribution to historical work on electronic literature.

Collection, Preservation, and Canonization

The dates that would in some ways be even more useful but that cannot be listed with any precision are the expiration dates of the works included in the ELC. How far out are we, for example, from the end of Flash, a technology abundantly represented in this volume? What provisions have we, as a culture or as individual artists, made to ensure that something of the work remains accessible even after the program that created it and the platform on which it runs are obsolete? Should we see these selections as performances rather than as durable artifacts, and the ELC’s relatively stable (and necessarily brief) descriptions of the works, illustrated with a single representative screen shot, as something on the order of “program notes” for ephemeral cultural phenomena like stage plays and political demonstrations?

Since its establishment in 2002, the Electronic Literature Organization’s Preservation, Archiving, and Dissemination project (PAD) has been in the forefront of the struggle to establish criteria and procedures for the preservation of digital literary artifacts. In 2003, the PAD project convened an international conference on these issues at the University of California-Santa Barbara, and in the following two years the ELO published two white papers outlining best practices for creating and maintaining sustainable digital artworks. These are Nick Monfort and Noah-Wardrip Fruin’s “Acid-Free Bits: Recommendations for Long-Lasting Electronic Literature” (2004) and “Born Again Bits: A Framework for Migrating Electronic Literature” (2005) by Alan Liu, David Durand, Nick Montfort, Merrilee Proffitt, Liam R. E. Quin, Jean-Hugues Réty, and Noah Wardrip-Fruin. Both are available on the ELO web site at http://eliterature.org. Hayles’ essay “Electronic Literature: What is it?” is the third installment in this series. In the context of its sponsor organization’s mandate, the first volume of the ELC must be understood as an act of curatorial conviction. It is not only an effort to document, to promote, and to make more accessible computer-based literary texts; it is an effort to tend the rich panoply of electronic literature that has emerged in the past decade, in the way that public gardens and monuments must be tended (and signposted) in order to survive, let alone to retain their social significance. In January 2007, a few months after the release of ELC 1, the ELO published a landmark essay by Katherine Hayles, “Electronic Literature: What is it?” Addressing a broad audience of “scholars, administrators, librarians, and funding administrators,” Hayles makes the curatorial aims of the ELC explicit, laying out a detailed history of the development of electronic literature as well as a rationale for its perpetuation. Hayles’ essay, along with EBR editor Joseph Tabbi’s set of recommendations for enhancing the ELO’s archiving and documentation practices, “Toward a Semantic Literary Web,” which was published at the same time, are to be considered companion pieces to ELC 1 and components of its crucial advocacy work.

Noble efforts of cultural preservation are always in a touchy do-si-do with the sometimes ignoble work of canon formation. In the case of ELC 1, the tact and broad-mindedness of the editors is abundantly evident in all choices they have made. It must have been difficult to select a representative set of sixty works for the first issue of what certainly will be the leading anthology of electronic literature, and only a few absences are truly palpable. There’s no sample of Young-hae Chang Heavy Industries’ fascinating and widely discussed Flash texts. The omission of Caitlin Fisher’s hypermedia novella These Waves of Girls suggests an interesting tension in relation to the ELO’s own history: in 2001 Fisher’s text won first place in the Fiction division of the organization’s Electronic Literature Award, leading to a certain amount of critical controversy. The winner in the Poetry division was John Cayley’s windsound, which is included in ELC 1. Other prominent early Web-based hypertexts that are missing from ELC 1 are Olia Lialina’s My Boyfriend Came Back from the War and Mark Amerika’s Grammatron.

Editorial modesty has apparently led to more serious omissions: nothing from the editors, three of whom have produced significant works of electronic literature, is represented in the collection. Where, for example, is Strickland and Cynthia Lawson’s V:Vniverse, or Monfort and Rettberg’s Implementation? If we are going to bother with canons at all, we should take the trouble to insist that writers as significant as Rettberg, Monfort, and Strickland make it through the door. Fortunately, canon building (and, more important, recognition and preservation) will not stop with ELC 1, and we can hope that upcoming volumes will rectify these absences.

Electronic Literature and Literature as Such

In addition to sheer convenience, especially for teaching purposes, one of the great values of literary anthologies, despite their inevitable omissions and biases, lies in their synoptic presentation of a period or movement within literary culture. The best anthologies, however, always resist a rigidly acute synopsis. The Electronic Book Review has itself recently confronted the vexed issue of anthologizing. Editor Joseph Tabbi’s Recollection in Process, a “gathering” of provocative contributions to ebr since the site’s inception, exemplifies the rational yet capacious selection process for collections that reflect the dynamism of active communities and discussions rather than the arid predictability of static categories. In emphasizing a commonality among the productions of numerous artists - a genre, a historical period, a “school,” a category of personal identity such as ethnicity or sexuality - they also provoke questions about what differentiates works within that domain. When we read anthologies, our consideration of particular selections inevitably puts pressure on the general rubric under which they have been selected, and through this dialectic we come to a richer understanding of the complex artistic, social, and historical phenomena of literary traditions.

In the case of the ELC, of course, “electronic” serves as the overarching rubric. The broad range and diversity of the collection’s technical keywords, however, point to the heterogeneity of this apparently unifying category, while the genre-oriented keywords indicate the same multiplicity as regards “literature.” If the ELO had been the MLA, it might as easily have come up with one of the evasive and unsatisfactory titles that grace some of the Modern Language Association’s official-but-fringe Discussion Groups - perhaps “Imaginative Writing Other than in Print.” Yet there seems to be something in “electronic,” “digital,” “computer-based” that does serve as an organizing principle for this domain of artistic endeavor, however difficult that principle might be to articulate. The ELO committee charged with creating a definition of “electronic literature,” led by Noah Wardrip-Fruin, determined that it is “work with an important literary aspect that takes advantage of the capabilities and contexts provided by the stand-alone or networked computer” (qtd. in Hayles, “Electronic Literature”). Since ELC 1 provides such a momentous occasion for reconsidering our presuppositions about the meaning of “electronic,” as well as “literary” and “important” and “capability,” I will frame the concluding section of my remarks by asking a question that will initially appear even more naïve and certainly a good deal more tendentious than Nell’s innocent “what are letters?”

What is at stake in maintaining that the difference between print and electronic literature is anything other than trivial? “Trivial” has, of course, a precise meaning in discussions of digital literature. Thanks to Espen Aarseth’s influential 1997 study Cybertext: Perspectives on Ergodic Literature, the “nontrivial effort… required to allow the reader to traverse the text” (1) has become the key differentiator of the categories cybertext and not-cybertext. In the decade since the publication of Cybertext, this distinction and the category “cybertext” itself have met with a range of critiques as well as further elaborations. I invoke the term here to point to the often- intractable difficulties in maintaining clear and critically productive boundaries between types of cultural phenomena such as literary texts.

In asking this question, I am in no way suggesting that nothing is at stake; on the contrary, I am seeking to underscore the urgency of the multifaceted project, carried on by many different artists and critics and editors, to consolidate something like “electronic literature” as a domain of creation and inquiry that can do justice both to the advancement and investigation of its material culture and to the philosophical, conceptual frameworks that guide that advancement and investigation. At the heart of this project is the relationship between protocols of computation and protocols of human language use, a relationship that despite all the critical attention it has received continues to present itself as vexed and indeterminate.

Current critical discourse on electronic literature must grapple with a problem Ron Burnett points to in his study of digital images. “At this stage,” Burnett argues, “digital artifacts are being approached and used as if they had a level of autonomy that is far greater than is actually possible. It is as if the material basis for the operations of digital machines had been metaphorically sidelined to confer greater power on them” (201). Our critical discourses can hardly be accused of sidelining the material basis of the literary application of computation. Taking to task both the presuppositions of academic cybernetic theorists such as Claude Shannon and the exuberance of popularizers like Nicholas Negroponte, the diverse contributions of Hayles, Mark Hanson, John Cayley, Matt Kirschenbaum, Jerome McGann, Rita Raley, and many others have insisted on the materiality of digital artworks, and in fact use the example of the digital to renew our attention to the materiality of literary texts as such. At the same time, however, in their laudable effort to turn literary criticism toward a critique of information theory’s idealism, critics have tended in the name of empiricism to focus on technical contingencies at the expense of considerations of how literary meaning comes into being and from whence it draws its aesthetic and social force. In a theoretical turnabout, criticism often confers on “the material,” and at times on “technology” itself, an agency and autonomy that is in the end no more philosophically defensible than the supposed agency and autonomy of bodiless, idealized information. A number of factors have contributed to this tendency toward a limiting empiricism, many of them perfectly valid critical positions in their own right. These include Aarseth’s carefully considered dismissal of semiotics from his theory-building project in Cybertext, as well as the important contributions to our critical discourse from the textual studies of Jerome McGann and Matt Kirschenbaum. For a compelling argument on the value of textual studies to the criticism of electronic literature, see Kirschenbaum’s “Materiality and Matter and Stuff: What Electronic Texts Are Made Of.” To some extent, Hayles’ command of the fields of cybernetics and information science, which she brings to bear with such panache in her critical writing, has also steered our focus toward pragmatic concerns, despite Hayles’ repeated plea that we strive for balance. To give requisite attention to these philosophical considerations, we must learn somehow to split the difference between idealist and empiricist orientations and grapple with the strange materiality of ideas, with literary texts as materializations of ideas, and with reading as the uptake and embodiment of ideas.

In making available a wide assortment of digital literary artifacts for discussion, ELC 1 goes a long way in setting the stage for such difficult investigations. Regardless of the categories we use in traversing the ELC, one feature all the selections have in common is that they are composed at least in part of written language. Even in the least conventionally “literary” of texts - such as Jason Nelson’s devious textual playthings (versions 1 and 2 of Dreamaphage are included in ELC 1) and Shawn Rider’s send-up of corporate advertising myBall - written and spoken language, as well as complex rhetorical figuration within that language, constitute indispensable components of the aesthetic whole. Though I am at times reluctant to agree with Charles Altieri, I find his attempt to give a dynamically relational account for what we experience as “the literary” apropos to the present context:

Literariness seems ultimately less a quality created by specific features of the work than a marker that we are expected to assume a willingness to take on in imagination the force that the work may be able to muster as a whole, as a specification of modes of agency and of consciousness capable of making demands on how we forge identifications. Literariness challenges us to examine who we become by virtue of the modes of participation within which we find ourselves engaged. (43)

Emphasizing the uptake of models into the imagination and the active participation with one’s own becoming that literature invites, if not demands, Altieri broaches the difficult domain of literary ethics. Literature matters, in part, because we sense, sometimes passionately, that it is “good for us,” that it is “a good.” Most of us, however, quickly resist any characterization of the goodness of the literary that reduces it to didacticism and turns literature into endless renditions of Aesop’s fables. Literature’s ethical power seems to derive, rather, from our encounter with the possibilities that inhere in our intersection, as particular readers at a particular time, with the general and historically durable systems of meanings in which both we readers and the texts we read are irrevocably implicated.

Literature, like the language in which it is written, is at once “in” its medium and “between” us; while grounded in the material means of its production and distribution, it is also suspended within its intralinguistic and intersubjective modalities of reception. Only as an instance of a shared language can electronic literature, or any literature for that matter, accede to meaning and, in turn, to cultural value and socio-political efficacy. In his 2002 riposte to Jeff Parker, Rettberg articulates a version of this problem in his critique of the anti-print biases of many critics of electronic literature:

If there is a defining flaw of the cybertext debate, it is a failure to take into account the “non-trivial effort” of “mere” interpretation that even lowly works of linear literature require. These crucial efforts of interpretation are further complicated by the additional constraints that cybertexts introduce into writing and reading practice.

More recently, Brian Kim Stefans has argued that “one cannot simply say that the word is another element to be treated like a sound or a color if one is to do justice to the notion of language as a very specific ability that humans possess, one that has been shaped by the sediments of conventions and conversations layered over several centuries.” Following the lead of Stefans’ critique of “the reduced emphasis placed on text as something that can be read” in discussions of electronic literature, my question can be reframed: in the field of literary criticism dealing with electronic texts, has our focus on “practical questions,” our concentration on the materialization and embodiment of the word in electronic literary texts, and, above all, our emphasis on the differences between print and electronic media led us to eclipse the radiant strangeness of written language itself?

“Letters that Matter” of course alludes to the title of Judith Butler’s 1993 book Bodies that Matter. In that text, Butler reminds us that

the process of signification is always material; signs work by appearing (visibly, aurally), and appearing through material means, although what appears only signifies by virtue of those non-phenomenal relations, i.e. relations of differentiation, that tacitly structure and propel signification itself. Relations, even the notion of différance, institute and require relata, terms, phenomenal signifiers. And yet what allows for a signifier to signify will never be its materiality alone; that materiality will be at once an instrumentality and deployment of a set of larger linguistic relations. (68)⏴Marginnote gloss5⏴Linda Brigham writes of how Hayles, in My Mother was a Computer, in her continued vigilance against technologically inspired monisms, has produced not only a critical book, but a riven, multifocal book, far from equilibrium.

— Lori Emerson (Oct 2007) ↩

Meaning, including literary meaning, emerges in a dialectical interaction between the material substrate of a symbol’s instantiation in a communication system and something else, an entity or a process that at once is and is not strictly “material.” While we have gone a long way toward establishing criteria for naming and accounting for the material instantiation of electronic literature, I submit that we have not come sufficiently to grips with this other dimension of the experience of the literary; even naming it “mind,” “consciousness,” “reception,” or “social relations of production” immediately encloses us in pre-posthuman philosophical traditions we might like to think we have shaken off. John Cayley, a practicing poet and critic operating in respectful tension with a number of strands of postmodern philosophy, has recently suggested that while print-based language can achieve some of the complex effects computer-based writing enables, “in so far as this is achieved it is achieved as concept, in the familiar and comfortable realm of literary virtuality, in the ‘mind’ and in the ‘imagination,’ but not in the material experience of the text and its language” (“Writing on Complex Surfaces”). This upholding of a “tangible,” “embodied,” “material” textual experience over a merely “mental,” “conceptual,” “linguistic” experience is one of the compelling dimensions of arguments for the distinctiveness and value of electronic literature’s materiality. Mark Hansen’s has provocatively articulated this argument within the broader domain of computer-based art forms. “Because of the crucial role it accords the computer as an instrumental interface with the domain of information,” Hansen argues, new media art opens up new avenues for our bodily as well as our intellectual engagement with artworks. Moreover,

new media art transforms this haptic prosthetic function into the basis for a supplementary sensorimotor connection with the digital. In the process, it helps unpack what exactly is at stake in the shift from an ontology of images to an ontology of information, from a world calibrated to human sense ratios to a world that is. . .in some sense fundamentally heterogeneous to the human. (123)

The computer-based art form we call electronic literature seems to be elbowing its way into a place between the information-image divide Hansen posits here. In all the works included in ELC 1, the letter is at once image and information, simultaneously the trigger of sensual experience and of cognitive expertise, as well as, in many instances, the stimulus to a bodily response. As the final lines of Toni Morrison’s novel Jazz and of Rainer Maria Rilke’s poem “Autumn” attest, print literature, too, has had the goal of pulling the reader’s body, as a reading instrument, as embodied cognition, into the virtual ethical-aesthetic zone of the text. In the conclusions of these texts, Morrison and Rilke call their readers’ attention to their physical hands, which are presumably engaged in the act of “holding” the book they are reading - an act onto which both writers confer powerful ethical implications. As we work to define (and extend) the category of “electronic literature,” a category that ELC 1 stocks with so many diverse examples, how do we account critically for the “important literary aspect” (Wardrip-Fruin, qtd. in Hayles, “Electronic Literature”) that interacts with the specific material features of the electronic textual object to catalyze, in the event of reading, a specifically literary experience?

As one of the foremost critics of electronic literature, ELC co-editor Katherine Hayles maneuvers nimbly through these theoretical conundrums. Much of her work is guided by the insight that “the view that the text is a immaterial verbal construction [is] an ideology that inflicts the Cartesian split between mind and body upon the textual corpus, separating into two fictional entities what is in actuality a dynamically interacting whole” (“Print is Flat” 86). Rather than tipping the balance of her critical attention toward a hypostatized “material,” however, Hayles’ analysis consistently emphasizes our need to appreciate “the specificity of new media without abandoning the rich resources of traditional modes of understanding language, signification, and embodied interactions with texts” (“Electronic Literature”). For Hayles, these modes of understanding include giving an account of the “something else” that emerges within a dialectic with literature’s materiality, whatever that strange entity might turn out to be. “In my view,” she argues in her conclusion to My Mother Was a Computer, “an essential component of coming to terms with the ethical implications of intelligent machines is recognizing the mutuality of our interactions with them, the complex dynamics through which they create us even as we create them” (243).

Just as physical matter requires human engagement to emerge as humanly meaningful “matters of concern” (Hayles, My Mother 3), so does the physical, graphical letter, whether ink-based or bit-based, require the event of reading to release its social efficacy. In The Diamond Age, the illustrated primer does not muster the Mouse Army of Chinese orphans by merely existing; the novel’s denouement depends upon Nell’s act of reading the primer and the transformations she undergoes in the course of that reading. Stephenson’s imaginary example of the primer, along with the 60 real examples of dynamic literary artworks gathered in ELC 1, prompt us to ask how we might get better at deploying our increasing familiarity with the protocols for the digital manipulation of information, along with our far more familiar (but no less difficult to master) protocols for the logical and tropological manipulation of grammar, to leverage the aesthetic, ethical, and socio-political potentials of the perennial, emergent strangeness of human language.

In bringing together so many beautiful and stimulating works of literary art, none of them the same, all of them “electronic,” and all of them decidedly “written,” ELC 1 and its eagerly anticipated future volumes will help to return us to such old but vital literary-critical questions from new perspectives. “At the early stages of an emerging technology,” Stephen Wilson has noted, “the power of artistic work derives in part from the cultural act of claiming it for creative production and cultural commentary” (10). Even if “the ELC” never attains the ubiquity of “the OED” or, for that matter, “the DSM-IV,” the work of Hayles, Monfort, Rettburg, and Strickland constitutes a vital contribution to our efforts to claim that electronic literature matters, not only in our personal and professional lives as writers and critics but also in our wider intellectual and public cultures. Furthermore, the ELC’s accomplishment encourages us to remain vigilant in questioning the theoretical presuppositions we bring to our reading of these texts, ensuring that our attempts to reflect “critically/politically/philosophically” on emerging work within the ever-widening (and yet still under-recognized and under-funded) domain of electronic arts and letters will continue, like letters themselves, to be good for something other than abbreviation.

Works Cited

Aarseth, Espen. Cybertext: Perspectives on Ergodic Literature. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins UP, 1997.

Altieri, Charles. “The Literary and the Ethical: Difference as Definition.” The Question of Literature: The Place of the Literary in Contemporary Theory. Ed. Elizabeth Beaumont Bissell. Manchester: Manchester UP, 2002. 19-47.

Burnett, Ron. How Images Think. Cambridge: MIT P, 2004.

Butler, Judith. Bodies that Matter: On the Discursive Limits of “Sex.” New York: Routledge, 1993.

Cayley, John. “Writing on Complex Surfaces.” dichtung-digital (2005). 25 May 2007. http://www.brown.edu/Research/dichtung-digital/2005/2/Cayley/index.htm

Coover, Robert. “Literary Hypertext: The Passing of the Golden Age.” Keynote address at the Digital Arts and Culture conference, Atlanta, GA, October 29, 1999. Published online in Feed Magazine in 2000; a copy of the text is now available at Nick Montfort’s web site. 31 May 2007. http://nickm.com/vox/golden_age.html

Funkhouser, Chris. Prehistoric Digital Poetry: An Archaeology of Forms 1959-1995. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama P, 2007.

Hansen, Mark B. N. New Philosophy for New Media. Cambridge: MIT Press, 2004.

Hayles, N. Katherine. “Electronic Literature: What is it?” Electronic Literature Organization. 2 Jan 2007. 31 May 2007. http://eliterature.org/pad/elp.html

- . My Mother Was a Computer. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005.

- . “Print is Flat, Code is Deep: The Importance of Media-Specific Analysis.” Poetics Today 25.1 (Spring 2004), 67-90.

Jackson, Shelley. “Skin Guidelines.” Shelley Jackson’s Ineradicable Stain. 31 May 2007. http://www.ineradicablestain.com/skin-guidelines.html

Kirschenbaum, Matt. “Materiality and Matter and Stuff: What Electronic Texts Are Made Of.” Electronic Book Review. 1 Oct 2001. 29 May 2007. http://www.electronicbookreview.com/thread/electropoetics/sited

Monfort, Nick. “Cybertext Killed the Hypertext Star.” Electronic Book Review. 30 Dec 2000. 31 May 2007. http://www.electronicbookreview.com/thread/electropoetics/cyberdebates

Monfort, Nick and Scott Rettberg. Implementation. 23 Jun 2006. 15 Sep 2007. http://nickm.com/implementation/

Rettberg, Scott. “The Pleasure (and Pain) of Link Poetics: A Riposte to Jeff Parker,” Electronic Book Review. 10 Jan 2002. 30 Apr 2007. http://www.electronicbookreview.com/thread/electropoetics/pragmatic

Stefans, Brian Kim. “Privileging Language: The Text in Electronic Writing.” Electronic Book Review. 5 Nov 2005. 31 May 2007. http://www.electronicbookreview.com/thread/firstperson/databased

Stephenson, Neal. The Diamond Age, or, A Young Lady’s Illustrated Primer. New York: Bantam, 1995.

Strickland, Stephanie and Cynthia Lawson. V:Vniverse. 2002. 15 Sept 2007. http://vniverse.com/

Tabbi, Joseph. “Toward a Semantic Literary Web: Setting a Direction for the Electronic Literature Organization’s Directory.” Electronic Literature Organization. 29 Jan. 2007. 31 May 2007. http://eliterature.org/pad/slw.html

Wilson, Stephen. Information Arts: Intersections of Art, Science, and Technology. Cambridge: MIT P, 2002.

Cite this essay

Zuern, John. "Letters That Matter: The Electronic Literature Collection Volume 1" Electronic Book Review, 9 October 2007, https://electronicbookreview.com/publications/letters-that-matter-the-electronic-literature-collection-volume-1/