Locative Texts for Sensing the More–Than–Human

Fostering a sense of connection or engagement towards the more–than–human world, or what David Abram has termed the “sensual world,” has the potential to allow humans greater understanding of our ecological place in inter–species communities. Digital artist Alinta Krauth enacts this understading with Diffraction, a mobile digital writing artwork that encourages users to experience a heightened sense of more–than–human relationality while outdoors. Krauth's practice–led research advances her argument "by using locative media, and emplaced play, as positive forces for considering our relationships with wild nonhuman Others."

In moments like this, something flutters open. Shifting fields of relations bloom. Wind stirs nothing. Not just my alertness and sudden attention, but the odd sensation of knowing that these trees, this creek, this bear, are all already alert to me in ways proper to each and despite my attention. Something flutters open, beyond this centered self. -David Jardine (182).

Fostering a sense of connection or engagement towards the more–than–human world, or the “sensual world” as Abram (ix) called it in his seminal text on the same topic, has the potential to allow humans greater understanding of our ecological place in inter–species communities. Biologist and philosopher Haraway (13) argues that this recognition of our inter–species network, as a form of more–than–human relationality, is imperative for moving forward when faced with issues of the Anthropocene such as the looming extinction crisis and changing climate. I take the position that through creative practice we can create new ways of fostering positive relations with our landscape and wildlife communities, a position strongly backed by creative practitioners (See: Liu, Byrne and Devendorf 2; Foth and Caldwell 8; Armstrong 1). An example of this is Diffraction, a digitally locative piece that uses Situationist–inspired narrative instructions, and place/time specific content, to draw the user’s attention towards engagements with flora, fauna, and geological actors in non–urban spaces.

However, two problems persist with using locative writing practices for this purpose: Firstly, digitally locative works are traditionally urban–focused and generally anthropocentric (Berry, 109; Tierney 253). Secondly, Abram argues that phonemic alphabets, and literature more generally, are barriers to our sensory engagements with the more–than–human (254). I respond in this article by arguing that digital locative experiences are a good candidate for fostering engagements in wilderness landscapes, due to its place–based nature. And secondly, writers of digital literature consider language and text within their works to be more than the written word, taking imagery, function, interaction, movement, mobilities, and sound, as literary devices that generate understanding (Funkhouser 10; “Interview with Jason Nelson” 1). My practice–led research aims to contribute to this argument by using locative media, and emplaced play, as positive forces for considering our relationships with wild nonhuman Others.

What is more-than-human?

Prominent global environmental issues such as climate change and species extinction are causing shifts in the discourses of arts and humanities research, towards those which are critical of human exceptionalism and anthropocentrism. Instead, values, ethics, and practices that are inclusive and equitable towards nonhuman life are slowly being approached. This distinction of nonhuman life has been adapted by researchers as everything from wildlife, such as in Jamie Lorimer’s Wildlife in the Anthropocene: Conservation after Nature, to the earthy and naturally–made environment, such as in Jussi Parikka’s A Geology of Media, through to the spirit world in the work of Abram (3) already mentioned.

The more–than–human world, a term used by Abram (ix) in 1997, has since sprung up as a more useful term than its sister terms ‘nature’, and the bifurcated term ‘human/non–human nature’ that semantically distance us from the rest of the world (Cianchi 32). To speak of the more–than–human world is to recognize us as just one part of an extensive natural universe within which we exist in “a communicative, reciprocal relationship with nature” (Cianchi 32). This stems from a system of thought, and an ethical standpoint, that has been recently attributed as an overcoming of scientific research and knowledge’s numbness towards its plant and animal subjects in western culture (Bastian, Jones, Moore, and Roe 2). Instead, to consider the more–than–human is to invite subjectivity and emotive reactions into traditionally objective encounters with plant and animal kin.

Abram (ix) argues that in order to connect to the more–than–human, we must re–attune our humanly senses toward place. For Abram, environment and the senses are inexplicably entwined. This is a notion reminiscent of biologist and biosemiotician von Uexküll’s explanation of creature senses from the early 1920s, commonly known as the theory of umwelt. Von Uexküll’s concept of umwelt states, among other points, that different species experience the environment based on sensory perception, therefore we may only understand our surroundings through our species–specific body (43). For Abram, this sensuous way of experiencing the world has been upset by our Western writing (52), with its phonemic nature that no longer points to imagery of the environment through its graphemes. He believes that such texts pull our attention away from a more fundamental sensory relationship with the environment around us, and cause us to believe ourselves uniquely separate from it (52).

Cianchi (34) argues that it is specifically more–than–human agency that marks the difference between nature as a passive force to be objectified, and the more–than–human world as a dynamic active force that we are in relationship with. While Cianchi (35) agrees with Abram that experiencing the more–than–human world is a fundamentally sensuous process with which we must engage, he adds that it is only once we perceive the agency of the non–human that we can recognize the nonhuman’s importance in a more–than–human world. Following Cianchi’s argument, the next logical step may be to consider ways in which we can encourage humans to see, engage with, and respond to such agency in an open dialogue across species lines (Plumwood 227).

Locative Dérive

The use of the term ‘locative’ to describe media digitally emplaced in a location via technology was first coined in 2002, and has since spread to consider works of art, narrative, and digital interaction that engage with place and social inclusion through technologies such as GPS, augmented reality, mobile applications, and mixed reality interfaces (Berry 110; Tuters and Vernelis 1). Combining this with the use of reading experiences contributes to what Berry (110) calls the “poetic landscape”. Such a poetic landscape sees text and poetry as having place–specific, and yet entirely mobile agency – creating a new layer of meaning that ties the literary directly to the land through locative media.

My understanding of locative texts is inclusive of the wide range of digital writing forms that can be made digitally locative – whether those be fiction, non–fiction, poetry, or other. This, and my understanding of locative media more generally, align with concepts from the Situationist International (SI) movement of the 1950s, ‘60s, and ‘70s, where artists designed new ways of socially engaging within the burgeoning loneliness of urban sprawl. SI contributors would use, among other urban gameplay elements, written suggestions for engaging differently to the accepted norm in a particular place. This gamification of social and environmental interaction, known as dérive, was designed as a way to get lost in one’s own city by performing unusual tasks. Dérive functions with an emphasis on the unexpected, which can add new layers of identity and place–making to the urban landscape (Berry 110). Contemporary locative media makers tend to use digital technologies and telecommunication networks to share these same themes of intervening with urban landscapes (Berry 109).

However, locative writing and artworks, including those that play with dérive and similar place–making concepts, have traditionally been attuned to practices of way–finding and emplacement that privilege anthropocentrism in urban landscapes. Moving these forms away from anthropocentric spaces and engagements, and towards more–than–human engagements, is an endeavor less commonly taken. And yet, locative works seem quite well placed to foster interactions between more–than–human elements of the world around us: Locative writing has a design focus on emplaced literary forms, as well as nonlinearity, rhizomic structures, interactivity, and multimodal sensory engagement (Hemment 2). Because of this, it may be a particularly potent contemporary art form for revealing tacit interactions between human and nonhuman actors.

Place and landscape have often served as a significant Other in locative works – the collaborator and emplacer of the user. One sees this in works such as Caitlin Fisher and Tony Vieira’s Chez Moi: Lesbian Bar Stories from Before You Were Born, where emplaced audio stories encourage users to make sensory connections with specific buildings, and the fleeting histories that may have occurred within and around them. This work is thus not just an engagement with text and story, but the facilitator of tacit engagements with surroundings through touch, smell, sound, taste, interaction, and any number of other sensory engagements that are suggested by the piece itself. This would appear to make the use of locative media a robust choice for developing more–than–human interactions in this work, as it allows the user to be positioned in place and space by mobile technological extensions.

Methodologies of more–than–human engagement through digital experiences

Considering methodologies for more–than–human engagements has blossomed in the form of participatory experiences, where the more–than–human world becomes an active partner in research (Bastian, Jones, Moore, and Roe 1). This has so far included, but not been limited to, methods that are mobile, and/or creative (Bastian, Jones, Moore, and Roe 3).

For my practice–led research that resulted in Diffraction, I have drawn on the sorts of participatory experiences that lend themselves to the phenomenology of Husserl and Merleau–Ponty: those which highlight sensory perception, experiences of the flesh, and performativity, in much the same way Abram ideated in 1997 (26). I also take into account postphenomenologist viewpoints such as Aagard (519), and Tripathi (200) who look to human–made technologies as an element of the more–than–human world. While phenomenologists such as Abram are largely skeptical of technological use in participatory experiences (Cianchi 28), creative practice–led research may be one way that the views of phenomenologists and postphenomenologists can intermingle, by showing how creative technologies and environmental experiences play together.

Diffraction

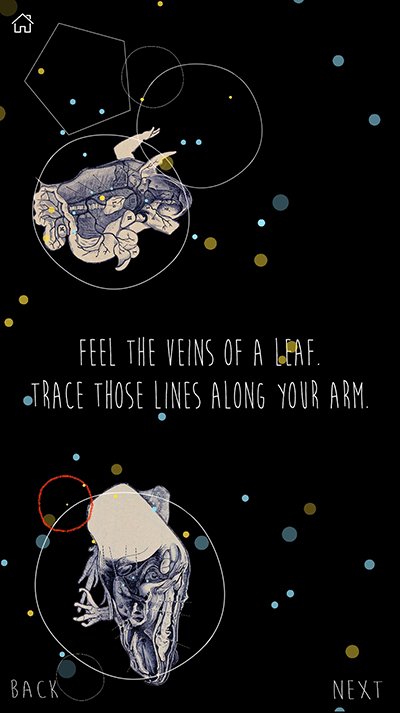

The Diffraction application is a mobile, interactive, and GPS responsive artwork that uses dérive–styled instructions made to act as a conduit for engaging with more–than–human agency through the senses. It was born from my work as a citizen scientist with the organization Wildlife Preservation Society of Queensland, including members from Griffith University’s biology department in Australia. Through this collaboration I was involved in a long–term fieldwork project surveying Gliders: a range of nocturnal Australian marsupials, which use a skin membrane between their front and back legs to glide between trees. Our project involved finding and documenting Gliders in their habitat in order to learn how habitat destruction was isolating populations.

During this study, I began to notice that when I considered scientific fieldwork as a creative and sensory game of Glider hide and seek, I began to interact with my environment in new and unusual ways. My interactions with the more–than–human began to favor the absurdist, as I attempted to subvert the logic–based quantitative methods I was following as a life scientist. For instance, instead of looking up into the trees, I asked whether I might be more open to engaging a Glider by performing absurdist language tasks, such as walking an amount of steps based on the letters in a particular word. This seemed like as good an idea as any in the dark silence of 2:00 in the morning when nothing else had yet worked. From this I was inspired to consider how a digital creative writing and arts practice could reflect and build on these experiences. This has directly steered the tasks given to the user within Diffraction: these tasks firstly attempt to diffract what we might perceive as normal human behavior in more–than–human spaces by asking the user to act in odd or absurd ways. Secondly, these tasks highlight sonic, olfactory, interactive, and tactile elements within a given location. In these ways, Diffraction attempts to use language to draw the user’s attention toward their sensory umwelt connections with the more–than–human world.

To use Diffraction, one must still rely on written language. This was chosen over other forms of representation for its swift and silent effectiveness in dark night, as the first iteration of this work was made for nocturnal use. However, Abram suggests there is a fundamental problem that exists in phonemic written language, “only by training the senses to participate with the written word could one hope to break their spontaneous participation with the animate terrain” (254). In other words, he suggests that the creation and use of the written word, as opposed to pictograph writing systems, interrupts our engagements with the surrounding environment. For Abram, this has set in motion an anthropocentrism borne of alphabets that now plagues Western society. This perspective is difficult to ignore, however language is not merely text and words; it is the wide range of ways in which we engage in communication with not just each other but the world around us – body language, touch, smells, and other ways that we present ourselves. This notion of a sensory language is implicit in the work of Abram himself (89), and inspired by the phenomenology of Merleau–Ponty (4). Abram sees sensory languages as being key to more–than–human engagement (256), as it opens us up to non–anthropocentric interactions, understandings, and communications.

Abram’s sensory language can be juxtaposed with the ways in which we read works of locative media, and digital literature more generally. Both Funkhouser (10), and Nelson (“Interview with Jason Nelson” 1) explain reading works of digital poetry and literature as the reading and interpreting of not just textual elements, but imagery, sound, movement, mobilities, technology, media, touch, smell, and interaction itself. These authors see sensory perceptions and bodily actions as potential literary devices that can be used inherently in the language of works presented digitally. I see this explanation of digital writing as highly reminiscent of Abram’s notion of sensory languages. Both consider engagement through a range of senses, bodily action and perception, and non–human agency, as vital forms of communication. Similarly, both attempt to look beyond phonemic alphabets to the range of sensory forms of communication that we have available in our umwelt. This potential for immersion into a digital writing work through the senses is perhaps made even stronger in locative works, which include full environmental immersion in place. Locative writing, in particular, would seem to serve not just as a platform for sensory language, but sensory language that specifically engages with the more–than–human world through the emplaced spatiality of the user.

I would not wish to suggest that locative literature and digital writing works are the grand answer to Abram’s concerns regarding phonemic language systems and the written word. However, it certainly seems a step in the right direction when one considers not just the viewpoints of Funkhouser (10) and Nelson (1) mentioned above, but the ways in which works of locative writing allow the user to interact more specifically with their environment and their own sensory perceptions, beyond text or story itself.

Future directions

Future possibilities for this research and its locative outcomes include further participant observation during hiking trips and other non–urban engagements. In this vein, Diffraction as a creative outcome has proven preliminarily interesting in questioning what odd, absurdist, and creative injections of Berry’s “poetic landscape” (110) can do for life sciences fieldworkers. This connection was made when some participants from my Glider study group were asked to use Diffraction during nighttime wildlife spotting routines, in order to consider how this may affect their experience with the more–than–human world. However, this preliminary involvement of participants is still ongoing.+++

References:

Aagaard, Jesper. “Introducing Postphenomenological Research: a Brief and Selective Sketch of Phenomenological Research Methods.” International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, vol. 30, no. 6, 2016, pp. 519–533. Taylor and Frances Online: doi:10.1080/09518398.2016.1263884.

Abram, David. The Spell of the Sensuous Perception and Language in a More–than–Human World. Vintage Books, 1997.

Armstrong, Keith. “Embodying a Future for the Future: Creative Robotics and Ecosophical Praxis.” Fibreculture Journal, vol. 28, 2016, http://twentyeight.fibreculturejournal.org/2017/01/23/fcj-211-embodying-a-future-for-the-future-creative-robotics-and-ecosophical-praxis/. Accessed 15 February 2017.

Bastian, Michelle, Owain Jones, Niamh Moore, and Emma Roe, editors. Participatory Research in More–Than–Human Worlds. Routledge, 2018. Taylor and Frances Online: doi.org/10.4324/9781315661698.

Berry, Marsha. Creating with Mobile Media. Palgrave Macmillan, 2018.

Cianchi, John. Radical Environmentalism: Nature, Identity and More–than–Human Agency. Palgrave Macmillan, 2015.

ELR. “Interview with Jason Nelson.” Electronic Literature Review, 20 Sept. 2015, https://electronicliteraturereview.org/interview-with-jason-nelson/#.XY7HTtMzZN1. Accessed 8 March 2019.

Foth, Marcus, and Glenda Amayo Caldwell. “More–than–Human Media Architecture.” Proceedings of the 4th Media Architecture Biennale Conference on – MAB18, 16 Nov. 2018. doi:10.1145/3284389.3284495.

Funkhouser, Chris. New Directions in Digital Poetry. Continuum, 2012.

Haraway, Donna Jeanne. Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene. Duke University Press, 2016.

Hemment, Drew. “Locative Arts.” Locative Media, 2013, http://locative.articule.net/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/Hemment_Locativearts.pdf. Accessed 13 April 2018.

Husserl, Edmund. Ideas: General Introduction to Pure Phenomenology. Routledge, 2015.

Jardine, David W. “‘All Beings Are Your Ancestors.’” Back to the Basics of Teaching and Learning, 2008, pp. 181–183. Taylor and Frances Online: doi: 10.4324/9781315096681.

Liu, Jen, Daragh Byrne, and Laura Devendorf, “Design for Collaborative Survival.” Proceedings of the 2018 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems – CHI 18, 2018. doi:10.1145/3173574.3173614.

Lorimer, Jamie. Wildlife in the Anthropocene: Conservation after Nature. University of Minnesota Press, 2015.

Merleau–Ponty, Maurice, and Thomas Baldwin. Maurice Merleau–Ponty: Basic Writings. Routledge, 2004.

Parikka, Jussi. A Geology of Media. University of Minnesota Press, 2015.

Plumwood, Val. Environmental Culture: the Ecological Crisis of Reason. Routledge, 2002.

Tierney, Thérèse F. “Positioning Locative Media: A Critical Urban Intervention.” Leonardo, vol. 46, no. 3, 2013, pp. 253–258. MIT Press Journals: doi:10.1162/leona00565.

Tripathi, Arun Kumar. “Postphenomenological Investigations of Technological Experience.” AI & Society, vol. 30, no. 2, July 2014, pp. 199–205. Springer: doi:10.1007/s00146-014-0575-2.

Tuters, Marc, and Kazys Varnelis. “Beyond Locative Media.” Networked Publics, The University of Southern California’s Annenberg Center for Communication, 2011, http://userwww.sfsu.edu/telarts/art511-locative/READINGS/beyondLocative.pdf. Accessed 13 April 2018.

Uexküll, Jakob von. A Foray into the Worlds of Animals and Humans: with a Theory of Meaning. Translated by Joseph D. O’Neil, University of Minnesota Press, 2010.

Cite this article

Krauth, Alinta. "Locative Texts for Sensing the More–Than–Human" Electronic Book Review, 3 May 2020, https://doi.org/10.7273/ppyv-fv21