Mapping Electronic Literature in the Arabic Context

In her essay, Egyptian elit scholar Reham Hosny observes and quantifies the ways that Arabic electronic literature has been historically underrepresented in the predominant critical venues like the ELO's Electronic Literature Collections and other central repositories for the dissemination and study of e-lit. Rather than simply observing this vacancy, however, Hosny proposes real, practical methods for addressing and bridging this discrepancy, bringing new works to light and encouraging translation, open access, and consideration of the language-based and nationalist biases in the scholarship surrounding elit.

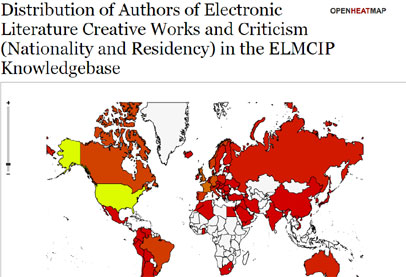

In his analysis of the data included in the Electronic Literature Collection, Volume 3 (ELC3) that was issued in February 2016, Leonardo Flores presents a map of the geographic distribution of the ELC3 authors (Fig. 1).

The fact that the white color, denoting a lack of representation, covers the Middle East and the whole continent of Africa struck e-lit scholars around the world as surprising. The causes behind this gap in the distribution of world e-lit authors has puzzled many researchers. Moreover, the situation becomes more provocative when we consider the fact that several e-lit communities have already existed since the turn of the 21st century in most of the white areas on this map.

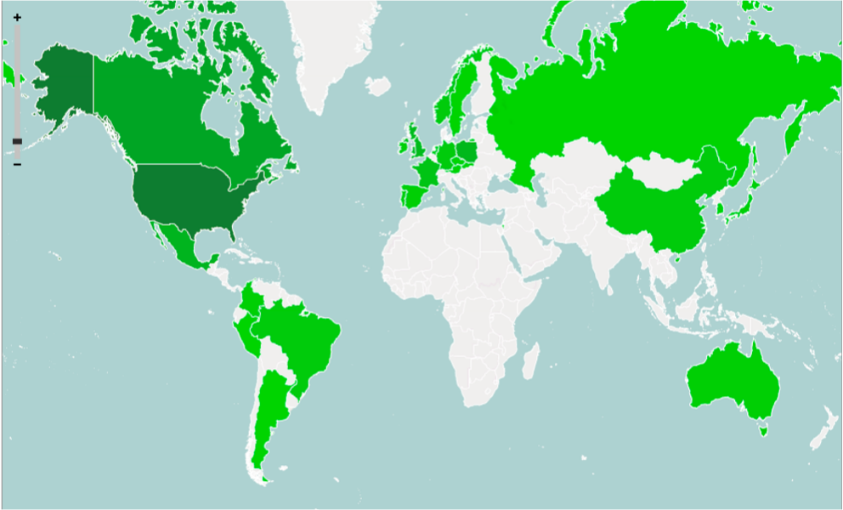

In the same analysis, Flores presents a pie chart for the ELC3 language distribution (Fig. 2) where some languages are well- represented, such as English with 50%, alongside works translated into English with 17%. Conversely, other languages such as Swedish, Arabic, Chinese, and Dutch are barely represented with 1%. This wide difference in representing authors and languages in the ELC3 provokes questions that urgently need to be addressed.

This study will address the reasons for the gap between ELC3 and Arabic author and language distribution and how we might begin to close this and offer some solutions. Moreover, the present context of Arabic e-lit will be investigated as a first step in the long process of putting Arabic e-lit on the world e-lit map.

The Turmoil of Arabic e-lit:

The current place of Arabic e-lit on the world stage is in turmoil. The following lines will investigate the reasons that might be behind this state of unrest.

- The Digital Divide and Language Barrier

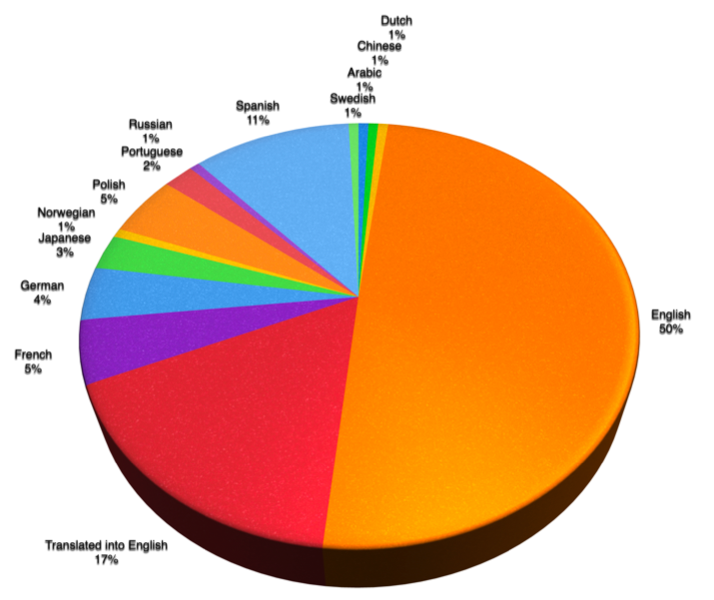

According to The Arab Knowledge Economy Report 2015/16, “The number of internet users in the Arab World [was] predicted to rise to about 226 million users by 2018” (Orient, March 29, 2016). However, there is a digital divide between the Arabic e-lit community and the international community. Comparing software and programing languages used in the Arabic e-lit context to those used in ELC3 (Fig. 3) a digital gap becomes clear. Up until now, Arabic e-lit artists and authors have not made use of software, programing languages, platforms, or techniques such as virtual reality, augmented reality, Twitter, installations, bots, locative devices, remixes, comics, games, Ruby, alternate reality, fanfiction, database, Kinect, Twine, netprov, performance, Perl, and Prezi.

There are neither artistic nor academic connections between the Arabic and the world e-lit communities. The same situation applies to programmers in both communities by adding the fact that the English language is the dominant language of programming. Language is a great barrier in creating networks between the two groups whether in e-lit or computer programming. Additionally, there are no works translated from other languages into Arabic in the field of e-lit, except for a few French e-lit articles translated by Mohamed Aslim.

The three ELCs do not include any works by Arab artists. However, the first ELC includes Like Stars in a Clear Night Sky (2006), written in Arabic and English by the Egyptian-American artist Sharif Ezzat who was classified as an American not an Arab artist. The same seems to have happened with the Lebanese-American Ramsey Nassir and his piece Alb (2016), a programing language written in Arabic to mock the hegemony of English in computer programing.

- The Mess of Terminology

There is an obvious confusion in drawing the borders of definitions in the Arabic e-lit scene. There are no clear-cut definitions for terms such as hypertext, digital literature, electronic literature, or interactive literature. Al-Buriky (2006) and Melhm (2014) use the terms “digital” and “electronic” interchangeably to refer to digital texts that do not provide the reader with chances for interaction, and texts that make full use of multimedia and allow the reader to participate in “interactive writing” (p. 75; pp. 30-31). According to Al-Buriky, there are two types of hypertext: “negative,” which does not provide the user with the chance to make changes to the presented texts and the links among them, and “positive,” which does allow the user to add, omit, and change the structure of the text, as well as to create a collaborative text written by several authors and reader (2006, pp. 22-23).

For Sanajleh (2005a) and Negm (nd.), digital literature is any text that is electronically published whether via the Internet, CD, or e-book. This literature is divided into negative digital text, which does not use the computer’s multimedia potentials because it is just a digitized text that can be printed, and the positive digital text, which is digitally published and employs the capabilities provided by digital and information revolution such as hypertext, audio and visual media, animation, and graphics. Sanajleh also presents the “digital reality novel” as a new concept in digital writing. His notion of digital reality novel is linked to the idea of a novel that is designed using the techniques of hypertext and a multimedia environment to depict the features of virtual society and the transformations that accompany human beings during their process of becoming virtual figures (2005b). With this description, Sanajleh defines not only the formal features of the digital reality novel, but also its content. Additionally, Yaktin (2005) and Yuonis (2011) use the term digital literature as an umbrella term designating two types of digital texts: the simple digital text, which is close to the paper book in its linearity, and a complex digital text, which benefits from the capabilities provided by digital devices and allows the reader to interact with its components (p. 142, p. 33).

This confusion in terminology is heightened in the Arabic e-lit scene for many reasons. Borrowing terminology from other disciplines such as computer science or game design provides literary scholarship with new horizons and perspectives. However, uprooting a term from its original milieu and implanting it in a new one could create some controversies. Take the example of the term “hypertext,” which appeared in the 1960s by Ted Nelson as a technological technique of linking chunks of texts by activating links and nodes. Hypertext represents the first generation of e-lit writers who adopted it as their main writing tool (Hayles, 2008, p.7) and triggers the controversy of whether using hypertext as a writing tool is a condition for the digital text to be labeled interactive or not.

Interaction between the reader/user and the digital text is a criterion that Al-Buriky (2006) uses to differentiate between digitized, digital, and electronic texts on the one hand, and the interactive text on the other hand (pp. 75-8). The range of the first category, for Al-Buriky, includes examples that range from digitized versions of paper-based literature to texts that employ programs such as Flash and programing languages such as DHTML and even hypertext, but do not consider interactivity as their primary technique.

But, what is the range of interactivity required to be labeled an “interactive reader”? Is clicking on hyperlinks considered “trivial” or “nontrivial” effort in the terms of Espen’s ergodics (1997)? Other arguments divide the influence of interactivity into two levels: “Interactivity appears on two levels: one constituted by the medium, or technological support, the other intrinsic to the work itself” (Ryan, 2001, p. 205). Such new terms brought from different disciplines create controversies in setting their references in the literary context.

Hayles (2008) argues that addressing e-lit with the same principles inherited from printed literature will not result in a genuine understanding of the field: “To see electronic literature only through the lens of print is, in a significant sense, not to see it at all” (p. 3). Although borrowing from structuralism and poststructuralism to understand and evaluate e-lit helps to consider it a continuation of the literary history, this same theoretical turn may also create a terminological and conceptual turmoil. Interactivity, for example, is considered by many e-lit theorists as a privilege of e-lit only, while it can be traced in some paper-based texts such as Raymond Queneau’s A Hundred Thousand Billion Poems (1961) and Mark Z. Danielewski’s House of Leaves (2000), as many scholars, including Hayles, have observed.

Translation also helps heighten terminological imprecision. The term hypertext, for example, is translated into many terms in the Arabic digital literary scene such as “alnas altasha’ubī,” “alnas almutarabit,” “alnas alfa’iq,” “alnas almumanhal,” “alnas almurtbit.” This labyrinth of terms is fortified in the Arabic context by the lack of academic collaboration between Arabic e-lit scholars and world e-lit scholars to come up with defined references for each term. The ELO’s definition of e-lit, “works with important literary aspects that take advantage of the capabilities and contexts provided by the stand-alone or networked computer,” to the best of my knowledge, is not known or used by any other Arab scholar at the time that I write this essay.

Moreover, the usage and popularity of digital literary terms differs from one culture to another. In the Arabic digital literary culture, hypertextual and interactive literature are two famous terms used to refer to literature that utilizes the capabilities of computer and provides the reader with the chance of interacting with the digital piece. In Europe, and specifically in France, although there is the same confusion regarding these terms, digital (numerique) literature is the most used term (Aslim, Sept. 4, 2012). In America, the well-known hypertext critics such as Landow and Bolter theorized and propagated the term “hypertext” during the first generation of e-lit. It can be said that ELO’s definition enjoys a wide circulation in American scholarship.

The same problem with terminology prevails in international e-lit community. This situation is confirmed by Sandy Baldwin in his introduction to Regards Croisés, because there is “no agreed-upon terminology” for this type of literature. For example, we see “publications with titles New Media Poetics, edited by Morris and Swiss or Electronic Literature by Katherine Hayles: the titles indicate very different fields, while the contents in fact deal with overlapping domains of practice and criticism” (Bootz & Baldwin, 2010, np.). For Aslim (Sept. 4, 2012), there are still no examples of e-lit that can be considered as models, which creates a fertile soil for such a chaos of terminology. However, Aslim believes that this phenomenon should not evoke any annoyance and that it will take time until there will be an acceptable sample of works, which enable researchers to create more stable terminology.

Arabic E-lit in the World Context

Comparing the Arabic conception of electronic, digital, interactive, hypertextual literature to their counterparts in different contexts will come up with new perspectives. Sandy Baldwin addresses the prevalent usage of hypertext as an efficient digital writing tool in seminal e-lit works, “the dominance of hypertext as a technique in the canonical works of the field gives it a primary organizing role” (Bootz & Baldwin, 2010, np.). Landow’s book is one important resource used by the Arabic digital literary scholarship addressing hypertext and theorizing its aesthetics as a continuation of the traditional literary theory of such experimental critics such as Barthes, Derrida, Genette, Bakhtin, ،Kristeva, Deleuze, and Foucault. This same claim can be found in Arabic digital poetics by Gourram (2013), Al-Buriky (2006), Melhm (2014), Yunis (2011), Yaktin (2005).

As observed by the ELO’s definition of e-lit quoted above, it is clear that the ELO community uses the terms electronic and digital interchangeably to refer to literary works that make full use of networked and programmable media. In the Arabic e-lit context, e-lit appears under different labels such as “interactive literature,” “hypertextual literature,” and “digital literature.”

Hayles (2008) argues that the ELO’s definition of e-lit, coined by a committee presided by Noah Wardrip-Fruin, does not define the “important literary aspects” meant to be evident in e-lit nor the range of “the capabilities and contexts” of computer which change and develop continuously (p. 3). Additionally, she herself works to define the features of e-lit: “Electronic literature, generally considered to exclude print literature that has been digitized, is by contrast ‘digital born,’ a first-generation digital object created on a computer and (usually) meant to be read on a computer” (p. 3). In this sense, digitized texts or word processing documents are excluded from the category of e-lit. According to Hayles, e-lit should be “digital born” and “read on a computer.”

Although Hayles develops a robust argument concerning the conditions for a literary piece to be electronic, an intriguing question is raised: is the printed generative poetry considered e-lit? Generative poetry is digitally born. What happens when generative poetry migrates from the digital to the print medium or when it ceases to be received as digital information? Generating poetry with software means that “the capabilities and contexts” of the computer are employed, which allows us to labels generative poetry as e-lit. Another key question is related to the printed born pieces that are transferred into digital pieces such as the printed poem “The Sweet Old Etcetera” by E. E. Cummings (1991, p. 275)that was translated into a digital work by Alison Clifford and included in the ELC2 as e-lit.

From the previous argument, it can be inferred that, for a literary work to be electronic, it should possess at least one of the following elements, which should be manifested in the work itself:

- Digitally written (e.g. generative poetry)

- Digitally received (e.g. interactive fiction)

- Cannot be printed out without losing its features. (Hosny, 2017b, p. 180)

Generally, according to Baldwin’s meta-analysis (2017, Jan. 7), current e-lit definitions could be divided into: a “formal/aesthetic” approach that deals with the formal features of e-lit (e.g. as in the definition put forward by the ELO); a “genealogical/ontological” approach, dividing e-lit into generations (e.g. Hayles’ argument about first generation or “classic” electronic literature and subsequent generations); a “communal approach” that is interested in the definition of e-lit in different communities (e.g. the ELMCIP Project based at the University of Bergen); and a “historical approach” that follows the discursive development of e-lit through ages (e.g. Lori Emerson’s discussion of “e-literature as a field”).

Anatomy of Arabic E-lit

For a closer investigation of the nature of the Arabic e-lit, it is important to analyze the digital components of the Arabic e-lit pieces available. In the following gathering of the accessible Arabic e-lit pieces (Fig. 3) some criteria are adopted:

Arabic pieces : All the pieces mentioned are written in the Arabic language or in Arabic mingled with other languages such as the Egyptian-American artist Sharif Ezzat’s Like Stars in a Clear Night Sky (2006), which is written in Arabic and English.

Accessible : All the pieces included in the following table are accessible by any reader. I checked the availability of each piece, in addition to providing links to these works in the primary resources bibliography. I excluded pieces only available to some readers. For example, Tabarih Raqamiyya Li-sira Ba’duha Azraq (Digital Agonies of a Biography Part of Which is Blue) (2007) by the Iraqi poet Mushtaq Abbas Ma’an, which is no longer available on its website, but which is still available on CD, was excluded. I also did not include the only Arabic digital theatrical performance Maqha Baghdad (Baghdad’s Coffee Shop) by the Iraqi theatrical director Mohamed Hussein Habib and other artists who, in 2006, did a theatrical performance via the Internet, because these are no longer available. The first Arabic e-lit piece, Zilal Al-Wahid (Shadows of the One) (2001) by Mohamed Sanajleh, was not included for the same reason.

Complete : All the included pieces were completed at the time of conducting this gathering. For example, I excluded Al-Moharibba (The Warrior), a Facebook novel by Abdelouahid Stitou, because it is still in progress.

Make use of networked and programmable media : All the included pieces use different kinds of digital media and/or programming language. I excluded digitized static pieces presented on screen, which make no use of the dynamic capabilities provided by computer media or make use of print-like platforms such as a blog.

Digital and printed computer-generated pieces : All the included pieces are digitally accessible and cannot be printed out without losing a lot of their features, or printed computer-generated texts such as Nassir Mou’nis’ Moharig Zradisht (2015) (The Zoroaster Clown), computer-generated poetry available as a printed book.

Additionally, in the case of works that are designed by the same software by the same author, one piece is documented to refer to the whole body of work such as the works by Mon’em Al-Azrak, Mohamed Chouika, and Labiba Al-Khemar.

In the table below, I provide basic bibliographical information about these works (columns 1-6). I also indicate which works fulfill specific criteria significant to the development of Arabic e-lit (columns 7-9). In particular:

Software : Does the work use a commercially-distributed software package such as Flash?

Hypertext : Does the work fall into the dominant paradigm of hypertext linking?

Programming** language**: Does the work make use of a programming language?

Hayles (2008) divides the tradition of e-lit into two generations, the first generation is represented by the “hypertext fiction characterized by linking structures, such as Michael Joyce’s afternoon: a story, Stuart Moulthrop’s Victory Garden, and Shelley Jackson’s Patchwork Girl” (p. 6). The second generation “makes much fuller use of the multi-modal capabilities of the Web … use a wide variety of navigation schemes and interface metaphors that tend to de-emphasize the link as such” (pp. 6-7). She perceives the works of the first generation as “classical” works, and the works of the second generation as “contemporary” or “postmodern.”

A close analysis of the Arabic e-lit works in the previous table (Fig. 3) reveals that the present generation of Arabic e-lit makes extensive use of hypertext. It also reveals that Flash, image, and sound are the most used media, and that HTML is a wide-spread programing language. Moreover, authors whose works depend on Flash need to find new ways to protect them from obsolescence.

However, a second generation is about to flourish, employing new media such as animation—for instance, Nissmah Roshdy’s The Dice Player (2013), and a group of artists in their piece Salome (2016). In addition, some artists like Abdelouahid Stitu’s Only One Millimeter Away (2013), are making use of new platforms such as Facebook. The second generation is also progressing towards a world e-lit community by writing their pieces in other languages beside Arabic language so that their work can be internationally accessible. This broad concept is compatible with my newly proposed concept of “Cosmo-Literature” which puts a conceptual framework of e-lit developed via new media as a way of globalizing e-lit (Hosny, 2017, Jan. 7).

The hypertext generation of Arab artists have not assimilated different types of digital technology and hence they seem to be unaware of new e-lit genres. Computer software is usually written in languages other than the Arabic language, which could be delaying Arab artists’ access to new digital technology. Moreover, the hypertext generation still deals with e-lit through the lens of paper-based literary poetics and classifications such as poetry, novel, and story. To address this gap between the Arab hypertext generation and the world e-lit community, I am leading an initiative, which began in Sept. 2015. The Arabic E-Lit network (AEL) intended to achieve many goals as noted on its website:

- Creating a website in English entitled “arabicelit” (launched in Sept. 2015), to globalize Arabic e-lit and discuss the related issues.

- Uploading the data of Arabic e-lit writers and their works upon the world databases of ELMCIP. We finished the first stage on October 17, 2015, by uploading the personal data of Arabic e-lit writers. The second stage will include uploading data about the creative works.

- Holding a multi-day conference on Arabic e-lit, which was held at RIT Dubai, Feb. 25-7, 2018. Many Arab and international writers who are interested in Arabic e-lit participated in this conference.

- Creating academic programs and workshops, publishing research papers about Arabic e-lit works and making comparisons with the international works to define the place of Arabic e-lit on the world map of e-lit.

- Creating networks between programmers and artists for a productive collaboration. (arabicelit, 2015)

The efforts of (AEL) started to pay off after uploading ELMCIP records dedicated to Arab e-lit artists. For the first time, thanks to visualizations performed by Scott Rettberg, the Arabic e-lit community is represented on a world interactive map (Fig. 4). By hovering over every country with the mouse, the name of the country and the number of its e-lit artists appear.

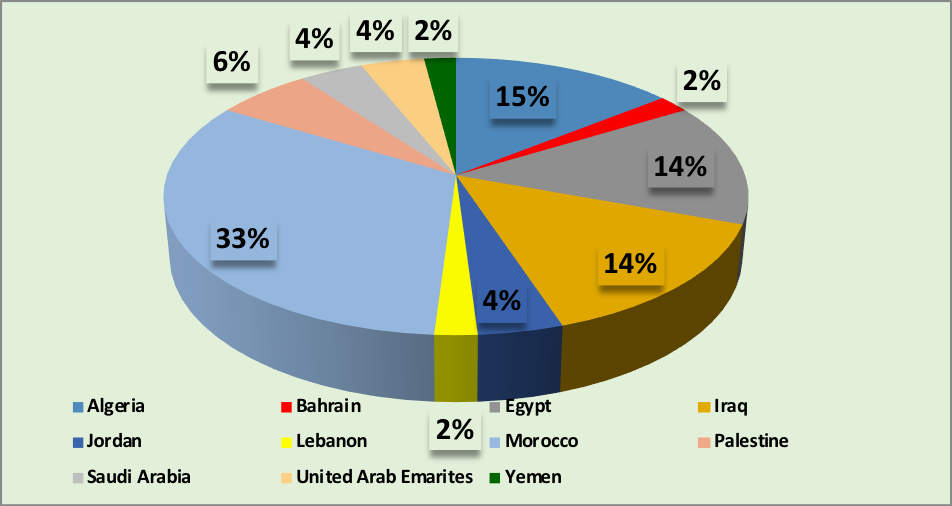

Moreover, a visualization of the number of Arab e-lit artists in every Arabic country could be created (Fig. 5)

As the graph demonstrates, the largest number of Arab e-lit scholars and artists is located in Morocco and Algeria with 33% and 15% respectively, followed by Egypt and Iraq with 14% for each. The reason that Arab e-lit scholars and artists are located predominantly in Morocco and Algeria is, in my viewpoint, that these two countries are more open to the European culture, specially French, where e-lit appeared many years before it appeared in the Arab World. This explanation is supported by the fact that up until now, the only practices for translating some e-lit articles into Arabic are from the French language.

Recommendations

Some urgent procedures should be considered for the development and continuity of e-lit in general and the Arabic e-lit in specific:

- Archiving Arabic e-lit : Digital media develop rapidly and some software programs become obsolete. Due to its interdisciplinary nature, which results from a combination of digital technology and linguistic text, some e-lit pieces can disappear. For instance, Tabarih Raqamiyya Li-sira Ba’duha Azraq (2007) by the Iraqi poet Mushtaq Abbas Ma’an is no longer available for the majority of readers after the breakdown of its website. National endeavors and projects should focus on archiving Arabic e-lit. Efforts in preserving and curating e-lit made by the ELO and specifically by Dene Grigar should be used as models of best practices.

- Translating Arabic e-lit : The second generation of Arabic e-lit tends to write works in Arabic and/or English. This is an indication that those artists believe in the importance of engagement with the world e-lit community. Translating Arabic e-lit into other languages will shed more light on the aesthetics and cultural specificities of Arabic e-lit. Moreover, it will secure a good place for the Arabic e-lit on the world map. On the other hand, translating world e-lit pieces into Arabic will develop new perspectives on the field.

- Collaborating with the world e-lit community : Joint projects between Arab and international scholars will provide wide-ranging explorations of the best practices for developing e-lit in general and Arabic e-lit in specific. The initiative of the AEL is the first in this context, which includes activities such as conferences, workshops, studies, and networks.

- Closing the digital divide : The culture of collaboration between the writer and the programmer has not been sufficiently promoted in the Arabic e-lit context. Moreover, most Arab writers do not have a solid background in programming and computer software. This context created a digital gap between the Arabic e-lit and its world counterpart. As explained before, the comparison between the digital technology used in the current Arabic e-lit and that used in the ELC3 resulted in a clear digital divide. Certain procedures should be considered such as holding digital creative writing workshops and creating chances for gathering writers and programmers in the same milieu.

- Developing Arabic e-lit pedagogy : It is obvious that “university curricula are the authentic gate for any discipline to be academically guaranteed” (Hosny, 2017a). In spite of this fact, “few Arabic universities have embedded it in their curricula.” It is the responsibility of Arab professors to develop e-lit courses in their curricula to help promote the production and reception of e-lit in the Arabic literary community.

While working on this paper, I tried to shed light on the gap between e-lit in the international and Arabic contexts as featured in ELC3. I moved on to address the reasons behind this gap by close analyzing many samples of Arabic e-lit. I resumed my essay by referring to recent Arabic e-lit efforts and recommending the best practices for the field.

In summary, Arabic e-lit is an emerging field of literature and for now, the field attracts many scholars and artists. Although there are some problems that hinder its progress in the Arab world, such as the absence of a stable terminology, the digital divide, and the language barrier, Arabic e-lit is a promising field of research and artistic practice.

References

Aarseth, E. J. (1997). Cybertext: Perspectives on ergodic literature. Maryland: Johns Hopkins UP.

Abdelghany, M., Elsawy, M., Abo Arab, S., Abdel-Salam, I., Pfenninger, J. (2016). Salome. Retrieved on Aug. 15, 2018: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wFECZK7qpSM

Al-Azrak, M.,Hamdon, T., Al-Sakaky, A., Fre, M., … Al-Mahaddaly, G. (2007). Almarsah [The Anchor]. Retrieved on Aug. 15, 2018: http://www.imzran.org/mountada/viewtopic.php?f=34&t=1229

Al-Buriky, F. (2006). Madkhl lladab altafa’uly [An introduction to the interactive literature]. Beirut: Almarkaz Althaqafi Al’araby.

Al-Azraq, M. (2007). Saīdat Almā’[The Water lady]. Retrieved on Aug. 15, 2018:http://imzran.org/digital/fla/saydatma.swf

Al-Khemar, L. (2017). Hizā’ Alhub[The love’s shoes]. Retrieved on Aug. 15, 2018: http://labiba-meroires.blogspot.com/2017/05/blog-post_55.html

Al-Mahaddaly, G. (2005). Aswad Ma Yuhit Bshqra’ Alna’mah[Dark around the blond ostrich]. Retrieved on Aug. 15, 2018: http://imzran.org/mountada/viewtopic.php…

Al-Sabah, S. (2005). Raqsh Sufīyyah[A Sufi dance]. Retrieved on Aug. 15, 2018: https://njwjof7zueaqhaitwp42rw-on.drv.tw/viewtopic.php_40t%3D624.htm

Arabicelit (2015). “About,” https://arabicelit.wordpress.com/about-4/

Aslim, M. (Sept. 4, 2012). Alruaīh al’arabiyyh alraqamiyyh ūqadiyyat almustalah [The Arabic digital novel and the case of terminology]. Retrieved on Aug. 15, 2018: http://www.aslim.ma/site/articles.php?action=view&id=108

Baldwin, S. (2017, Jan. 7). “Against global electronic literature: Challenges and tactics.” Presentation at the MLA 2017 Conference, Philadelphia.

Bootz, P., & Baldwin, S. (eds.). (2010). Regards Croisés: Perspectives on digital literature. West Virginia University Press: Morgantown.

Chouika, M. (2009). Ihtīmalāt [Possibilities]. Retrieved on Aug. 15, 2018: http://www.chouika.com/

Cummings, E. E. (1991). E. E. Cummings: Complete Poems 1904-1962. G. J. Firmage (Ed.). New York: Liveright Publishing Corporation.

El Bouyahyaoui, S. & Al-Khemar , L. (2014). Hafanāt Jamr [Bunches of embers]. Retrieved on Aug. 15, 2018: http://narration-zanoubya.blogspot.com/2014/07/blog-post_930.html

Ezzat, S. (2006). Like stars in a clear night sky. Retrieved on Aug. 15, 2018: http://collection.eliterature.org/1/works/ezzat__like_stars_in_a_clear_night_sky.html

Flores, L. (Mar. 31, 2016). “Towards a global electronic literature collection” [PowerPoint slides]. Retrieved on Aug. 15, 2018: https://www.slideshare.net/leonardoflores3/towards-a-global-electronic-literature-collection

Gourram, Z. (2013). Aladab alraqmi as’ilah thqafiyyh ūta’mulat mafahimiyyh [The Digital literature: Cultural questions and conceptual contemplations]. Rabat: Dar Alaman.

Idris, A. (2010). Saīdat Alīahū [The Yahoo Lady]. Retrieved on Aug. 15, 2018: http://www.imzran.org/mountada/viewtopic.php?f=3…

Hamdawy, G. (2016). Aladab alrqami bain alnazariyyh ūaltatbiq [The digital literature between theory and praxis]. Retrieved on Aug. 15, 2018: http://www.arab-ewriters.com/booksFiles/12.pdf

Hayles, N. K. (2008). “Electronic literature: What is it?” Electronic literature: New horizons for the literary. University of Notre Dame Press.

Hosny, R. (2017a). “E-Lit in Arabic Universities: Status Quo and Challenges.” Hyperrhiz, (16).

Hosny, R. (2017b). “Mn Aldada ila algava: Aladab alīlīktroni bain alnash’ah ūal tataur” [From Dada to Java: Electronic literature between genesis and development]. A conference paper presented at the Arabic language and literary writing on the internet Conference book, KSA, Feb. 14-16, pp. 176-191.

Hosny, R. (2017, Jan. 7). “Understanding Cosmo-Literature: The extensions of new media.” Presentation at the MLA2017 Conference, Philadelphia.

Melhm, I. (2014). Alraqmiyyh ū tahaulat alkitabh [Digitality and the Transformations of writing]. Jordan: Modern Book World.

Mou’nis, N. (2015). Moharig Zradisht [Zoroaster’s clown]. Netherlands: Dar Al-Makhtotat.

Nasser, R. (2013). Alb [Heart]. Retrieved on Aug. 15, 2018: http://collection.eliterature.org/3/work.html?work=%D9%82%D9%84%D8%A8

Negm, S. (n. d.). “Alnas alraqami ū ajnasuh” [The digital text and its genres]. Al’arabi alhur.Retrieved on Aug. 15, 2018: https://ueimag.blogspot.com/2016/11/blog-post_630.html OrientPlanet Research. (March 29, 2016). “Arab knowledge economy report 2015/16.” Retrieved on Aug. 15, 2018: http://www.orientplanet.com/Press_Releases_AKER2015-16.html

Rettberg, S. (June 7, 2016). “Distribution of authors of electronic literature.” Retrieved on Aug. 15, 2018: http://www.openheatmap.com/view.html?map=InversingParachutismBemuzzle

Roshdy, N. (2013). La’ib Alnard [The dice player]. Retrieved on Aug. 15, 2018: https://vimeo.com/69830884

Ryan, M. L. (2001). Narrative as virtual reality. Immersion and interactivity in literature. Maryland: John Hopkins UP.

Sanajleh, M. (2005a). “Altafa’uli ūaltrabuti ūalraqami ūalwaqi’ alraqami” [The interactive, hypertextual, digital, and digital real]. Middle East Online. Retrieved via this link

Sanajleh, M. (2005b). Riuaiat aluaqi’iyyah alraqamiyyh [The Digital reality novel]. Beirut: Almu’asasah Al’arabiyyah Lldrasat ūalnashr.

Sanajleh, M. (2005). Shat [Chat]. Retrieved on Aug. 15, 2018: http://www.mediafire.com/file/5vzqbac75n6d7c5/chat%26saqee3.zip

Sanajleh, M. (2006). Saqī’ [Frost]. Retrieved on Aug. 15, 2018: http://www.mediafire.com/file/5vzqbac75n6d7c5/chat%26saqee3.zip

Sanajleh, M. (2016). Tuhfat Alnizarah fī ‘aja’ib Alimarah [A gift to those who contemplate the wonders of the emirate]. Retrieved on Aug. 15, 2018: http://dubai.sanajleh-shades.com/

Sanajleh, M. (2016). Zilal Al’ashiq [Shadows of the amorous]. Retrieved on Aug. 15, 2018: http://sanajleh-shades.com/other-accounts-of-the-author

Stitu, A. (2013). Ala bu’d mlimtr wahid faqat [Only one millimeter away].Retrieved on Aug. 15, 2018: https://www.facebook.com/rewayaonline/

Stitu, A. (2015). Almutashard [The tramp]. Retrieved on Aug. 15, 2018: https://www.facebook.com/almotasharid/

Tawfiq, A. K. (2002). Rab’ Makhifa [Makhifa alley]. Retrieved on Aug. 15, 2018: http://www.angelfire.com/sk3/mystory/interactive.htm

Tawfiq, A. K. (2015). Kuhuf Dragosan[Dragosan’s caves]. Retrieved on Aug. 15, 2018: https://download-stories-pdf-ebooks.com/21660-free-book

Yaktin, S. (2005). Mn alnas ila alnas almutarabit, madkhal ila jmaliyyat alibda’ altfa’uli From text to hypertext: An introduction to the interactive creativity’s aesthetics. Casablanca/Beirut: Almarkz Althqafi Al’arbi.

Yuonis, E. (2011). Internet impact on patterns of literary creation and its acception in contemporary Arabic literature. Retrieved on Aug. 15, 2018: http://www.researchgate.net/publication/281543457

Cite this article

Hosny, Reham. "Mapping Electronic Literature in the Arabic Context" Electronic Book Review, 2 December 2018, https://doi.org/10.7273/qsvk-3z16