Monstrous Weathered: Experiences from the Telling and Retelling of a Netprov

A consideration of Monstrous Weather, a recent netprov (or networked improvisation) and the ways that collaborative storytelling encourages the rereading, retelling, rewriting, and adaptation of stories that begin as performances, and then turn into a form of archiving through still further rereading, rewriting and retelling. Author Alex Mitchell begins by depicting how, during the original performance of Monstrous Weather, there was a constant reworking, remixing and retelling of texts, both literally and through references and embellishments. This process gradually coalesced the loose collection of story fragments into something that had a kind of coherence, if not as a story, then at least as a storyworld. Mitchell discuss two particular performances/remixes: a live reading of excerpts from the netprov performed at the Electronic Literature Organization (ELO) Conference 2017 almost exactly 1 year after the initial performance, and a subsequent hypertext remix/archive.

We retell—and show again and interact anew with—stories over and over; in the process, they change with each repetition, and yet they are recognizably the same. (Hutcheon 177)

There are texts that haunt us, that cannot and will not be forgotten, texts that seem to have strong if often mysterious claims over our memory, attention, and imagination and that urge us to reread them, to make them present in our mind again and again. (Calinescu ix)

In this paper I discuss Monstrous Weather (Meanwhile… netprov studio), a recent netprov, or networked improvisation (Wittig, “Literature and Netprov in Social Media: A Travesty, or, in Defense of Pretension”), considering ways that this form of networked, collaborative storytelling encourages the rereading, retelling, rewriting, and adaptation of stories both as part of the act of performance during the netprov, and after the performance as a form of archiving through rereading, rewriting and retelling. I begin by exploring how, during the original performance of Monstrous Weather , there was a constant reworking, remixing and retelling of texts, both literally and through references and embellishments. This process gradually coalesced the loose collection of story fragments into something that had a certain amount of coherence, if not as a story, then at least as a storyworld. Stepping back, I consider the process going on behind the scenes, in the form of rehearsals and backchannel discussion, that led to an initial set of story fragments that were then reworked and “performed” in the context of the “live” netprov. Beyond the end of the performance, there was a desire among the participants to see the work continue in the form of adaptations, remixes, and further performances. I discuss two specific performances/remixes: a live reading of excerpts from the netprov performed at the Electronic Literature Organization (ELO) Conference 2017 almost exactly 1 year after the initial performance, and a subsequent hypertext remix/archive. Through my analysis of Monstrous Weather , I explore the central role of rewriting, retelling and repetition in this type of networked, collaborative performance.

What is Netprov?

Networked technology, in many forms, has long been repurposed for storytelling. As Rettberg describes, early online collaborative storytelling projects such as Coover’s Hypertext Hotel , a collaborative hypertext document created by Coover and his students, and Rettberg, Stratton, and Gillespie’s collaborative hypertext novel The Unknown , made use of Internet technology to connect people to create and share stories. These works involved a limited group of participants, and took place within custom-made websites. As social media platforms began to proliferate, people began to use these technologies as a medium for collaborative storytelling, capitalizing on the fact that people may or may not realize that what they are encountering is fiction. Netprov represents one approach to this appropriation of networked technology for collaborative storytelling. A form of creative, imaginative play, netprov involves groups of collaborators using existing platforms such as Facebook, Twitter, and Reddit to create and share stories. According to Wittig, netprov is

… a way of using existing digital media in combinations to create fake characters who pretend to do things in the real world… they induce a moment of vertigo where people don’t quite know whether it’s real or not—‘was what I’m reading written by a real person, or is it fake?’ (“Pasts and Futures of Netprov”)

An example of this is Wittig and Marino’s OccupyMLA, in which three fictional characters tweet about the plight of non-tenured faculty members, claiming to have “occupied” the Modern Language Association. Reading the comments on the Chronicle of Higher Education article in which the authors explain their performance (Wittig and Marino, “Occupying MLA”), it is clear that many who encountered the work did not initially recognize that it was a work of fiction. In addition, those who did notice it was fictional did not always appreciate the satirical nature of the work, instead taking offense at its “cartoonish” portrayal of adjunct faculty members. Perhaps one reason for this was the fact that many readers failed to appreciate that each individual tweet was actually part of a “larger, interconnected story that would require immersive reading” (Berens). This suggests that this type of dispersed, performative, transmedia storytelling is creating, through echoes, repetition and reinterpretation of both real and fictional people and event, not simply a series of micro-fictions, but instead the basis for a larger, fictional storyworld.

What is Monstrous Weather?

To understand this process of creating a fictional storyworld from a fragmented set of micro-fictions through rewriting, retelling and rereading, it is worth looking in more detail at a recent netprov, Monstrous Weather. Inspired by the 200th anniversary of the night that Mary Shelley, Percy Shelley and Lord Byron sat together during a spell of monstrous weather and told ghost stories, participants in the netprov were encouraged to “summarize a scary story somebody told the week the internet was down.” Organized by Rob Wittig and Mark C. Marino under the auspices of their “Meanwhile… netprov studio” brand, the netprov played out in a dedicated Google Group, with participants either posting their stories as new threads, or responding to existing threads with follow-up stories or remixes of previous stories.

Although Wittig argues that “netprov is clearly a make-believe game or a mimicry game” without rules (“Literature and Netprov in Social Media: A Travesty, or, in Defense of Pretension”), Monstrous Weather did have a set of rules, laid out at the start of the performance. These rules clearly framed the performance in terms of a (fictional) retelling, with remixing and creating connections between stories established as a fundamental part of the “play” of the piece:

- In 300 words or fewer, summarize a scary story somebody told the week the internet was down.

- Who told the story? When and where? What happens in their story?

- Include one bit of weird weather.

- See if your story can reply to another story. Answer, amplify, remix! Or start a new topic with a new story.

As I will argue, although these rules were not always followed by participants, the underlying approach laid out in rule 4, that of retelling and remixing, was clearly a thread that ran through the entire performance, and that continued through the subsequent retellings and adaptations.

The netprov was originally scheduled to run from 20 July to 10 August 2016. Entries that can be considered part of the performances were posted to the group between 21 July and 14 August, at which point the performance came to an end. I took part in the netprov as a first-time participant, having seen the announcement of the performance posted on social media. As I will discuss below, the performance continued to live on in various forms, including a live reading at the ELO 2017 conference in Porto, and a hypertext remix/archive. It is this continuous reworking, retelling and rewriting, both within and beyond the original performance of Monstrous Weather , that I will focus on in this paper.

Tellings, micro-retellings, and the development of a storyworld

I will begin by characterizing the modes of participation in the netprov and describing the process that took place as the performance progressed from an initial, fragmented set of posts to the gradual development of a series of interlinked postings that began to create the feeling of a (somewhat) consistent storyworld. In particular, I will examine the role of remixing and “micro-retellings” in the performance of the netprov.

Describing the features of the netprov form, Wittig distinguishes between the “inner circle” or “featured players” in a netprov, and the more casual “outer circle”. As Wittig describes,

[t]he collaboration of the inner circle is modeled on theatrical improv. The participation of the outer circle of readers is modeled on networked role-playing games, and on fan participation in mass media fictional “worlds.” (“Literature and Netprov in Social Media: A Travesty, or, in Defense of Pretension”)

For myself as a casual, first-time participant in the netprov, I was clearly part of the “outer circle”. It is difficult to agree with the characterization of this participation as that of a “reader”, or at least as a reader in a passive sense. As Rebei explains, an active reader “becomes both an interpreter of texts and a producer, that is, a writer of further texts. In sum, through his/her reading a reader can rewrite the text he/she is reading” (49). In the case of a netprov such as Monstrous Weather , this shift from reader to writer/rewriter is not merely an internal, cognitive process, but a literal rewriting of and contribution to the text of the work. This makes Wittig’s comparison with role-playing games or fan fiction feel more accurate, as the “outer circle” readers such as myself were actively encouraged to contribute new text to the performance.

An important point to note here is that for me, as a new participant in this type of performance, there were a number of aspects of the dynamics that I was not aware of at the start. In this section I will describe the process that I observed as a member of the “outer circle”, and how I perceived the development of the performance from that perspective. In the next section I will step back and reflect on the fact that, for the “featured players”, there was actually another layer of collaboration taking place both before and during the “public” performance which was not evident to those in the “outer circle” (including myself).

Initially the stories being posted as part of the performance were self-contained, making use of the “weird weather” theme but having little else to connect them. These stories adhered fairly closely to the pattern, as laid out in the rules, of recounting a story that someone told to you “the week the internet went down”. For example, Reed Gaines’ short piece “Turbulence” recounted being stuck in an airport and hearing a story about a time when the entire planet was covered in a thick layer of clouds. Similarly, Rob Wittig’s “A Green World” told a story he claimed to have been told, recalling the day that soap stopped working. Linked by the rules and structure of the netprov, and by the framing theme, these stories stood alone and felt thematically related, but did not form any sort of coherent, connected narrative. While not yet manifesting the type of rewriting and retelling that later became a key feature of the netprov, there was already, in the use of the framing device of retelling, an acknowledgement of the notion that stories are “told in order to be retold” (Kroeber 1).

Gradually, however, the importance of referencing and retelling came to the foreground, as posts began to make reference to each other, sometimes as the result of an author mentioning another author’s name (as fictionalized versions of the actual author), and at other times by referring to events depicted in earlier posts. Interestingly, the first of these interconnected posts occurred soon after a real-world weather event, a storm in Minnesota, which took several of the “featured players” offline and rendered them temporarily unable to contribute to the performance. One of the organizers, Mark C. Marino, posted “out of character” about this event, and then followed this with two postings mentioning weather quite similar to the real life events: Scott Rettberg’s “It is Dark Now”and his own “A moment’s respite”. These two posts were quickly followed by a pair of postings that are representative of two forms of echoing and remix that often occurred throughout the performance. In “A moment’s respite”, Marino framed his tale as being told by Davin Heckman, another of the “featured players” involved in the netprov. This use of (semi-fictionalize) versions of other performers was a frequently used technique, one that helps to increase the feeling of vertigo that Wittig describes as an essential part of netprov, the feeling that the reader is never sure “‘was what I’m reading written by a real person, or is it fake?” (“Pasts and Futures of Netprov”). As a member of the “outer circle” I experienced this vertigo directly. I was only vaguely familiar with some of the featured players and their existing relationships, so I was not always certain which of the events and characters being mentioned were fictional, and which were fictionalized versions of actual events and people.

In addition to blurring the boundaries of the fiction, the technique of making use of reference to netprov participants by name within the fictions also tended to trigger responses from the participant who was named. In this case, although Marino’s contribution was actually a reposting of a fragment originally shared in the private “rehearsal” forum, Heckman responded with his own new post, “Boom”, which made direct reference both to the real-life storm, and to several of the featured players who lived in Minnesota (post 1 in the thread). This was followed by a reply, within the same thread, by Jeremy Hight (post 3), which took the text of Heckman’s post and reworked it, retaining some of the sentences but deleting others, interjecting new phrases, and generally “riffing” on, or building from and improvising around, the original text. For example, the first part of Heckman’s text:

There was no storm in Duluth. I was just up in Cloquet, and it was fine. Hot, yeah. But no storm, at least not down where I was. Yeah, they say the power’s out up there. That might be true. And I haven’t heard from anyone, except very vague “we’re ok… the power’s out… it’ll be a few days…” I tried to message Joellyn, Rob, some other folks. And either, it’s not them or something has scared them or something has happened to them. I’m willing to believe something happened up there, even, something significant. But it wasn’t a storm. There was “the boom,” of course.

Became, in Hight’s version:

There was a small storm in the syllables of “Duluth”. It was not of sky and rain. There was no hail breaking to freefall. There were no rains as cold breath. There was no water skinned by lightning, veined by what breaks the air superheated into thunder. There was no giant serpentine mass of cloud defying gravity , water droplets formed on airbornes broken insect wings, grass clippings and dust.

It is fine. That might be true. But it wasn’t a storm. There was “the boom,” of course.

Here we can see both the references in Heckman’s original text to the real-world events in Minnesota (the “storm in Duluth”), and the distorted echoes of Heckman’s text in Hight’s remix (“There was no storm in Duluth” becomes “There was a small storm in the syllables of ‘Duluth’”). This echoing and remixing, at the micro level of individual posts, became quite common across the performance, lending a strong sense of interconnectedness to the posts. What we can see here is the beginning of what Sawyer describes as a “group riff” in the context of jazz and improv theatre, where lines or scenes in a sketch are repeated and reworked, and patterns start to emerge within improvisation, both within and across performances.

This remix approach was something that was actively encouraged by the organizers. As Marino and Wittig suggested in their instructions to the “featured players” on the public launch of the netprov:

Someone asked about revising others’ stories. We can use the principle Rob [Wittig] developed for Invisible Seattle’s Omnia (IN.S.OMNIA) years ago: leave the original and add your own remix, DJ style. Replying to a story in a Google Group forum topic should work great for this.

This use of remix began to create overarching themes within the performance, with recurring images and phrases, such as the “boom” in Heckman and Hight’s text, coming back and being echoed in later posts. For example, much later, as part of an unrelated but interconnected sequence of story fragments, Wittig (post 7) brought in what appears to be a reference to this earlier sequence:

Jean pushed back from the table — another fantastic meal she’d whipped up without electricity — and told this story. Where she gets her energy I’ll never know!

I was spelunking when the furmd blew, she began. That’s how I missed it, or it missed me. I scrambled back to surface when I heard the boom.

I could tell instantly that everyone on the surface had forgotten a bunch of short-term stuff. Everybody was talking about it. Parking lots full of people trying to find their cars. People sitting in restaurants, pissed that their dates hadn’t arrived. Or happily having a solo meal and surprised when their date showed up.

But it took a lot longer for me to cotton to the fact that something bigger had been forgotten.

At the end of the second paragraph, within the story that Jean is telling, there is a clear reference to a “boom”. This was echoed in a follow-up post by Hight (post 8), where Wittig’s text is remixed and condensed from 10 sentences down to 4 sentences, but the “boom” is retained:

Jean pushed back from electricity — spelunking.

I heard the boom.

People trying to find their cars. People sitting in restaurants, but something bigger had been forgotten.

This remixing, reuse, and the use of references to earlier story fragments gradually began to create a sense of something approaching a consistent underlying storyworld. An example of this can be seen in two separate but seemingly related threads, “belly” and “Earl”. The “belly” sequence, initiated by Hight, begins with a poetic description of clouds drifting low over a town (post 1), remixed by Hight himself into a somewhat more mournful passage with hints of funerals and death (post 2). This was followed by a fragment by Wittig (post 3) which took a more narrative approach and described a “cloud funeral”. This passage mentioned me by name, and I followed it with an elaboration on the notion of the cloud funeral (post 4). Hight followed this (post 5) with a remix of both his own original postings and those posted by Wittig and myself, mentioning us both by name. Wittig (post 6) and I (post 7) both followed up, bringing the short narrative arc to a close. Interestingly, this sequence was followed, a few days later, by a new series of postings by Hight, in which he described the sorrowful end of Earl, likely a reference to Hurricane Earl that had struck the Atlantic coast of Mexico a few days earlier.

Whether it was intended or not, for me the “Earl” sequence felt intimately connected with the earlier sequence, “belly”, helping to create a feeling that there was a larger, if not necessarily entirely consistent, storyworld underlying these posts. Although there was never a completely cohesive “fiction” created over the three weeks of the performance, there was still a strong sense that all of these micro-fictions were building upon each other to form an interconnected structure. Despite the fact that there was no deliberate attempt by the participants to create a single “product” or work of fiction during the performance, there was an emergent process at work, what Sawyer describes as somewhat similar to composition. However, as Sawyer explains, “unlike composition, neither the individual nor the group has the intention of composing a product; rather, it emerges unintended from the improvisational process of performance” (63).

The feeling I had of the performance as a coherent, crafted piece became most evident in the final few posts, where a sequence emerged that seemed to represent an attempt to bring some sense of closure to the larger fiction. The second-last thread in the performance, Joseph Tabbi’s “A decade or two on…”, looked back from a future in which the Internet has not returned, and communication is reduced to Morse code and messages passed around on scraps of paper by bicycle messengers. This post was followed by a sequence of fragments, by Hight and myself, that made reference back to the various threads throughout the performance, ending with a short passage in which an unnamed character reflects on and then deletes a story. In a separate, final thread, “fog knows no borders or human ends”, Hight described a landscape where the fog, oblivious to the troubles of humans, settled on the land and was burned away by the rising sun. From an initial jumble of seemingly unrelated but thematically connected fragments, through to the interconnected “belly” and “Earl” sequences, and finally culminating with Hight’s poetic conclusion, for me as a member of the “outer circle” I felt that across the roughly three weeks of the performance there had been a gradual, seemingly organic movement towards a sense of both an ambiguous and yet compelling storyworld, and a strong sense of closure.

From rehearsals to “live” performance

My description of the Monstrous Weather netprov performance and the role of remixing and references between posts in creating a sense of a larger storyworld has so far largely relied on my position as a “reader” or a member of the “outer circle”. Stepping back, it is worth looking at what was happening behind the scenes, within the “inner circle”. Although the performance, from my perspective in the “outer circle”, seemed to be happening in real time with minimal planning or backchannel communication, as with many improv performances the “featured players” had actually been working together for some time, including on a number of earlier netprovs, and had in fact spent three weeks before the public launch “rehearsing” the performance. As Wittig explains, “[w]ithin the fiction texts appear to be written in real time; in fact they can be prewritten and scheduled for later release” (“Literature and Netprov in Social Media: A Travesty, or, in Defense of Pretension”). This was something that I was not aware of at the time, and only realized when I was “inducted” into the “featured players” group roughly a year later. In this section, I will describe what I understand to have happened behind the scenes, based on access I gained to additional online resources once I was a member of the “inner circle”.

The “featured players” make use of an additional, private Google Group, set up by Marino and Wittig for use in a number of their netprovs. For Monstrous Weather , Marino and Wittig created a dedicated thread in the group, where they announced the netprov and encouraged players to work on their stories. In addition to the thread in the main Google Group, Marino and Wittig also set up a private Google Doc, where members of the “inner circle” were encouraged to post their stories. As Marino and Wittig explained in the introductory posting:

We are experimenting with a week of the theater-based notion of “rehearsals” — what writers might call drafting and visual artists might call sketching, Featured Players can try things out in a private google doc (above) and then we can all nominate our own most successful pieces to the public netprov.

This rehearsal period ran for just over 3 weeks, from 30 June to 20 July, at which point the “live” Google Group was created, and invitations were sent out to the public.

Having later been invited into the “featured players” group, I was able to see the archive of the rehearsals both in the Google Group and in the Google Doc. Looking through this archive, I quickly recognized many of the postings, although some of them had been edited before being reposted into the public forum, and most interestingly, the order of postings was quite different. In particular, I realized that both “It is Dark Now” and “A moment’s respite”, which had been posted immediately after the storm in Minnesota, and (to me as an outsider) appeared to be written in response to that event, had actually been posted much earlier in the “featured players” private Google Group. This was part of the strategy encouraged by the organizers, as described in Marino and Wittig’s post to the private group announcing the start of the public performance, “Public Launch of Monstrous Weather!”:

Please repost your stories to the public group…You can repost them all at once … or languorously tantalize us … making us wait on tenterhooks as … drip, drip, drip … you slowly, etc.

Much of the same form of remixing and building off each other’s’ posts that I described above in the context of the public forum could also be seen in the private forum. There was, however, much more backchannel or “out of character” communication, with participants commenting on each other’s’ stories, providing encouragement and suggestions for improvement, and at times prefacing their own postings with some descriptive remarks or explanation of the context. This clearly highlights the difference between being in a “performative” context, with the presence of an audience, albeit an invisible, online audience, and working in the “safe” private space of the rehearsal group. As Sawyer explains, “[r]ehearsal enables interactional synchrony to be established more quickly, but it also makes the group performance more predictable” (65), suggesting there is a tension between the need to build trust and work through possible “group riffs”, while at the same time avoiding creating too much familiarity and the associated potential loss of spontaneity.

Once the “live” netprov was launched, participants did begin to post their pre-written materials, but gradually there was a shift from reposting and reworking existing material to creating more “new” material. It wasn’t clear to me how much of this was in response to interactions with participants in the “outer circle” such as myself. Regardless, there was a clear shift from rehearsed to “live” material, although even in the final few days, some material was still surfacing that had appeared in the rehearsal phase. This suggests that the materials developed during the rehearsal phase can be seen as what Sawyer refers to as “ready-mades”, short precomposed motifs, stock phrases or story fragments that performers can draw upon as material from which to build their performance.

Interestingly, once the performance went “live”, it appears that there were no more posts in the rehearsal space. Although the private Google Group was still active, and was returned to for rehearsals of subsequent netprovs, it appears that during the “live” performance there was none of the type of backchannel discussion that had happened during the rehearsal. It is not clear why this was the case. It may be that there was a tension between “performing” live and potentially disrupting the authenticity of the live performance by discussing the direction of the performance during the duration of the performance itself. This is something that has been observed in other forms of online, computer-mediated collaborative storytelling (Mitchell et al.). However, given the asynchronous nature of the netprov, and the fact that this type of backchannel communication does, in fact, take place in other forms of online, collaborative storytelling such as forum RPGs (Alley), it may be worth investigating further why this was the case in the Monstrous Weather netprov.

Despite the lack of activity in the private forum during the live performance, there was an active effort made by some of the participants, particularly by Wittig, to continue to “archive” subsequent posts made in the live forum to the Google Doc. As a member of the “outer circle” during the original performance, it was very interesting for me to look at this “archive” of the performance and consider the similarities and differences between these versions of the work. By the end of the performance, there were essentially 3 versions of the “traces” of the work – the posts from the rehearsal that had been captured, as they had been posted, in the private Google Group; the traces of the “live” performance, also as it was posted, in the public Google Group; and finally the Google Doc that had formed part of the rehearsal “space” which contained the remnants of the rehearsal, the additional material added by Wittig and others during the performance, and also, accessible by means of the “view history” function of Google Docs, a trace of the edits made during the rehearsal and the live performance. As Wittig has reflected, “it’s difficult to know exactly how to think about netprov projects. There’s a live performance aspect, but at the same time it leaves a trace—if you’re lucky.” (Wittig, “Pasts and Futures of Netprov”) This highlights the fact that there isn’t ever a clear “true” archive of this type of performance, raising the question of how to document and archive networked collaborative performances.

To help gain some insight into the issue of archiving and performance, I will discuss two additional archives or retellings of the Monstrous Weather netprov that were created after the end of the performance proper: a live reading of excerpts from the netprov at the Electronic Literature Organization conference in Porto, Portugal in July 2017, and a hypertext “remix” of the netprov that I developed based on the public Google Group archive.

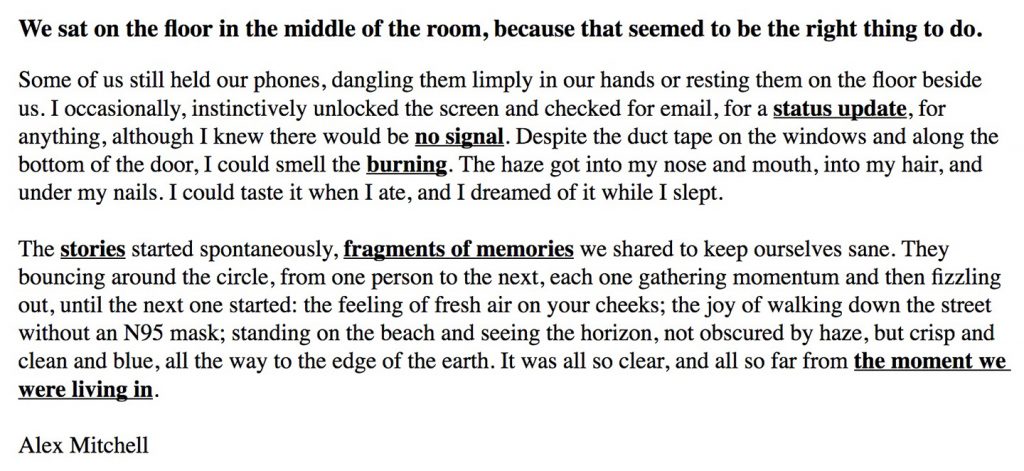

The desire for it to “live on” – a live reading of the netprov

Following the end of the netprov, several of the authors expressed enthusiasm for continuing the performance in some manner, such as a book or series of live readings. Some participants did in fact embark on adaptations of all or part of the netprov in a range of other media, including a PDF release of the “Thor in Minnesota” thread, and interactive adaptations in platforms such as Twine. Suggestions were also made for an adaptation as an art installation, a Google maps version, and possibly even a version printed on umbrellas. Finally, several of the authors performed a reading of selected story fragments at the Electronic Literature Organization conference in July 2017 (see Figure 1). In this section, I will discuss how this live reading can be seen as a form of remixing and archiving.

The performance at ELO 2017 was somewhat impromptu, with Wittig suggesting via the Monstrous Weather public Google Group that it would be fun to organize “An Evening of Monstrous Weather” involving some of the original participants. Once the conference was underway, Wittig posted the following message: “The plan today is simply to form a small circle of chairs on the outdoor patio adjacent to the lunch room and read some Monstrous Weather aloud for our own delight and that of anyone else who cares to listen.” A number of the participants assembled after lunch, some having brought specific selections of their own to be read, and others choosing favourite pieces from other participants. Sitting in a circle of chairs, quite appropriately echoing the framing narrative of the netprov, we took turns reading selections from the performance, which was live-streamed on Twitter by Marino.

The traces of the original performance as archived in the public Google Group now became the script for a new performance of what had previously been an improvised work. The length of the pieces, usually roughly 300 words, was very appropriate for live readings, as each excerpt when read aloud tended to last roughly 2-3 minutes. When presented verbally rather than in a written form, the pieces because spontaneous in a different manner, allowing for subtle edits in the process of reading from the text, and incorporating non-verbal cues such as intonation and body language. As the performance was also streamed online, with some of the 110 viewers posting brief comments or “hearts” through the Periscope interface, an additional archival trace of the performance was created. I will briefly discuss several of the readings, highlighting how these represent an interesting retelling and remix of the original netprov.

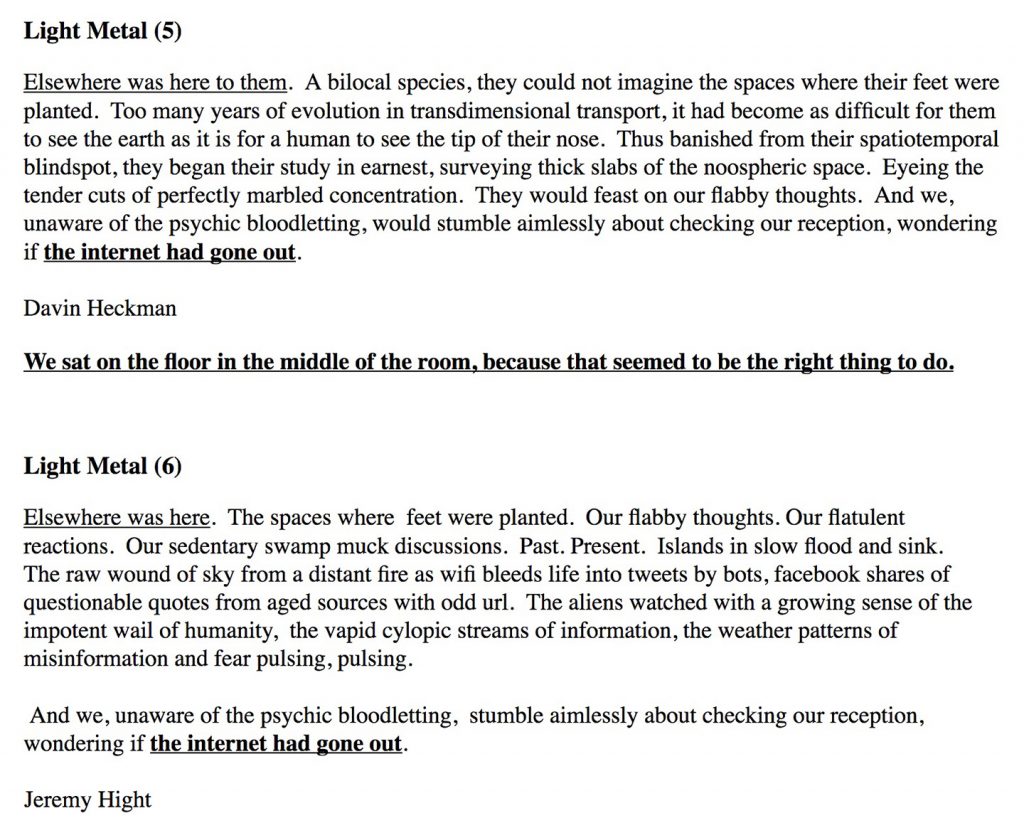

The selection of pieces performed represented a cross-section of the overall netprov, and echoed the type of interconnections and remixing evident in the online collaboration. For example, towards the start of the live performance, Rob Wittig, Davin Heckman and myself read from the “Light Metal” sequence written by Wittig, Heckman and Jeremy Hight. This sequence starts with a short passage by Wittig (post 1), followed by a response from Heckman (post 2), a further response from Wittig (post 3), and a final pair of responses from Heckman (posts 5 and 7). Similar to his remixing of Heckman’s text in the Boom sequence discussed above, here Hight posted a remixed version of Wittig’s second passage (post 4), and of Heckman’s response to that passage (post 6). The sequence ended with a new piece by Hight (post 8), following on and quoting, but not directly remixing, Heckman’s final piece.

This remixing and repurposing was echoed in the live performance, where Wittig and Heckman read out the initial three posts in the thread (posts 1-3), after which I read Hight’s remix (post 6) of Heckman’s response (post 5) to Wittig’s post (post 3), rather than Heckman’s actual post. Finally, Heckman read out his final post (post 7), ending the sequence. This performance of selections from the sequence collapsed the remixes and the original posts into a single thread of responses, creating a sequence similar to the original but adapted to the new, live performance context, in which a literal repetition of the original and remixed passages would likely not be as effective as it had been in the original screen-based presentation, as much of the impact of this type of remix comes from the visual comparison the reader can make between original and remix.

This alteration in the presentation of the materials highlights the different affordances of the verbal versus the written medium, something that also came across in the performance of an excerpt from Scott Rettberg’s “Thor in Minnesota” thread. Here, Rettberg began by reading out the initial post, prefaced by a short commentary in which it because clear that, as with the “Boom” thread, this post was a response to the storm in Minnesota, as well as to the Republican National Convention that was taking place at that time. The first post in the sequence introduced Thor as the source of the storm, and made reference both to Rob Wittig and the ongoing Monstrous Weather netprov as the cause of Thor’s anger and the resulting storm. In response, Wittig had posted a fragment in which he bought a goat as a sacrifice to appease Thor, following which Rettberg posted a fragment describing the sacrifice of the goat and leading into the larger narrative arc.

In the live reading of the sequence, Wittig read out his response, and during Rettberg’s reading of his follow-up, Wittig also read out the dialogue spoken by the fictionalized “Rob” who was sacrificing the goat. This incorporation of the spoken voice of Wittig the netprov organizer and participant into Rettberg’s fiction, using Wittig to read out the lines spoken by the fictionalized “Rob”, effectively highlights the blurring of the real and the fictional that is at the core of netprov. By having Wittig read out “his” lines, the repetition, interconnections and references between the various posts was also foregrounded in a much different, and more immediate, fashion than had been the case in the original netprov performance. Whereas text affords remixing and visual comparison between versions, spoken word here seems to instead afford the interesting juxtaposition of speaker and character, foregrounding the nature of the remix and the interconnections between the various fragments in the netprov.

Later in the same sequence, Thor’s servants Þjálfi and Röskva speak. At this point, Rettberg asked one of the audience (who had not taken part in the netprov) to read out the lines for these two servants. It isn’t clear what position this audience member was occupying. She was a “reader” of the netprov in the more traditional, passive sense, one who, unlike members of the “outer circle”, had not contributed new text to the larger work. However, now she was stepping out of the role of audience and taking on the role of a performer of the pre-written script derived from the traces of the improvisational, online, text-based performance. Again, this serves to highlight the complexities involved in the reworking and retelling of the netprov, where the roles of reader, writer, audience, and performer are all in flux.

Adapting and retelling as a form of archive

According toHutcheon,the fundamental appeal of literary adaptation “comes simply from repetition with variation, from the comfort of ritual combined with the piquancy of surprise. Recognition and remembrance are part of the pleasure (and risk) … so too is change” (4). This can be seen in my adaptation of the entire netprov in the form of a hypertext, implemented using the HypeDyn procedural hypertext authoring tool. Here, I will discuss the process of crafting this adaptation from the traces of the netprov, explore how this relates to the processes of rewriting and retelling that seem to be central to the netprov form, and briefly reflect on how this process can be seen as a form of archive through repetition.

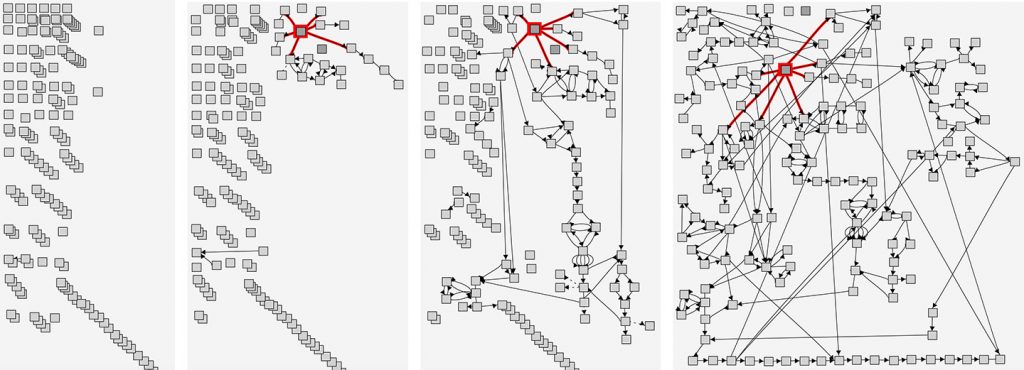

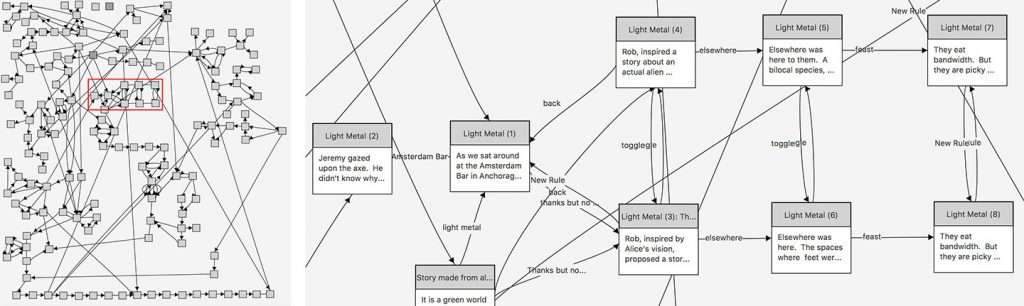

Preparing to rework the netprov as a hypertext initially involved a detailed rereading of the public Google Group archive. It is important to acknowledge here the close connection between rereading and rewriting. According to Rebei, “rereading, understood as a second, subsequent reading to a first reading will, through the new interpretations that it produces, add to the known textual meanings and thus open the possibilities for rewriting” (40). My intention in adapting the netprov was to capture something of the interconnectedness that I have described in the sections above, while at the same time look for some way to balance the exploratory nature of hypertext with the movement towards a conclusion and some form of closure as represented by the final few posts in the performance. After rereading the entire performance in chronological order, I started to get a clearer sense of the connections that I had noticed when taking part in the initial performance. I decided to retain the content of the posts as much as possible, focusing on remixing the connections between the nodes rather than remixing the textual content of the nodes. I began by creating a collection of 154 nodes based on the individual posts in the netprov, and then gradually began creating connections between these nodes (see Figure 2).

An early decision I made was to set up a “hub and spokes” pattern, where the reader would continually return to a single node, with links leading off from that node to clusters of related stories. I chose to use my own posting, “El Nino”, as the centre of the hub (see Figure 3). As the text of this post made explicit reference to the act of telling stories, it felt appropriate to use this as both a framing narrative and as a place for the reader to return to and then branch out to other stories. I created links leading out from the “hub” node to several story fragments, which themselves led to related fragments. Making use of HypeDyn’s sculptural hypertext functionality, I made the hub node into an “anywhere node”, which automatically adds a link back to the hub node from all other nodes in the hypertext. This provided an anchor for the reader as she explores the various loosely-connected story threads, ensuring that the reader could always return to the centre where the stories were being told, without fear of becoming lost in the tangle of story fragments.

Having set out the overall intended structure of the work, I began linking from the central “hub” to several clusters of stories. Within these clusters, I tried to use hyperlinks to reflect the connections, references and remixing that I described earlier. A good example of this can be seen in the “Light Metal” sequence (see Figure 4). Here, I made use of the echoing between Wittig and Heckman’s original posts and Hight’s remixes as the basis for the link structure, creating what Bernstein would describe as a COUNTERPOINT or perhaps, given the way that Hight’s remixes echoed rather than followed the original posts, a MIRRORWORLD.

Here I made some changes to the order in which the nodes were linked, as compared to the temporal sequence of the postings in the public Google Group. I felt that Heckman’s response (post 2) to Wittig’s original post (post 1) was somewhat of an aside, whereas posts 3 and 4, posts 5 and 6, and (to some extent) posts 7 and 8 directly echoed each other, and also formed a progression in pairs. To capture these relationships in the hypertext, I created links between the two paired posts, allowing the reader to essentially “toggle” between the original and Hight’s remix of each post, and also to move on to the next pair. To emphasize the relationship between the original and remixed post, I placed the “toggle” links on text that was similar, but not identical, in each of the posts in the pair (see Figure 5).

I followed a similar approach with other collections of posts, creating COUNTERPOINT patterns between remixed posts, and linking together sequences that seemed to be either thematically or more directly narratively related. As I linked in more fragments, I started to see more connections between what had earlier seemed to be a loosely related collection of posts. Examples included connections that I had not originally seen between the interconnected “belly” and “Earl” threads mentioned earlier, and both the “rains” and “Data Trees” threads, and the “Weather Underground” and “The Sea” sequences. I also started to find possible references across the entire story, often centered around the storm in Minnesota mentioned earlier.

Given the “hub and spokes” structure I had used to structure the overall story, plus the many connections between the threads within the story, I faced a challenge in terms of bringing the story to a conclusion. In the original netprov performance the final sequence of posts brought a natural sense of closure to the work. I wanted to bring a similar sense of closure to the hypertext version, without imposing an overly linear structure. To allow for this, I decided that once all the links leading out from the “hub” node had been followed, the final paragraph of the “hub” would become visible, and a link would become available that leads to the final sequence, “A decade or two on…” (see Figure 6). At that point, the links to the various story threads are still available, but once the reader follows the link to the final sequence, those outgoing links are disabled. The “sculptural” link back to the hub is still active, and the reader can always use the “back” button provided to move back over the story and explore links not followed, but there is no longer any way to move out from the “hub” node other than towards the ending. By doing this, I was trying to encourage, but not force, the reader to move into the final sequence.

Although I wanted to let the reader move through the story even after the final sequence was “unlocked”, I did hope that they would, at that point, decide to move towards the ending. To further encourage this, once the reader reaches the final node of the “A decade or two on…” sequence, the link back to the hub is replaced with a link to the final post in the netprov, “fog knows no borders or human ends”. Wherever they go in the story, either using the back button or by following links from previously visited nodes, the link to the final node appears at the bottom of the current node. Once that final node is visited, no more links are visible. The persistent reader could still make use of the back button to revisit earlier nodes and explore alternative paths through the story, but the most likely thing for them to do is to stop reading and bring the experience to a close. This structure funnels the reader towards the ending, leaving some freedom of navigation but strongly encouraging a movement towards closure.

At this point it is worth considering how the rewriting and weaving together of the various nodes in my hypertext version of the netprov relates to the rewriting, remixing and interconnections that took place in the earlier performances of the work. What I was involved with here, as I reread the text and worked to find connections across the various posts, is what Calinescu refers to as reflective rereading, or looking for connections and deeper meanings in a text that has already been understood at the surface level. There is a strong connection between this type of rereading and rewriting. Connecting rereading to Barthes’ notion of active reading, Calinescu feels that this type of rereading is “active, productive, ultimately playful, and it truly involves the reader in the pleasure of (mentally) writing or rewriting the text” (46). This directly reflects the process I was undergoing as I was rereading and then rewriting the Monstrous Weather netprov as a hypertext.

By repeating the experience of reading the traces of the netprov, first in its “raw” form as posts in the public Google Group, and then as I wrote and rewrote, revised and remixed the connections between these story fragments as I stitched them together in my hypertext version of the performance, I was essentially revisiting and repeating my original experience as a member of the “outer circle” of participants as a way to archive that experience.

Rereading, Rewriting, and Repetition as Archive

The idea of repetition as archive is something that Kartsaki discusses in the context of performance art, where she suggests that the archival function of repetition is not just a record, but also the source of possible future versions of a work:

So, what kind of archive does repetition create? … its peculiarity lies in the fact that this is not a fixed or finished archive; it is more like repetition itself, a shape of sorts, a cast, a supple structure. Such a structure is both now and then, here and there. It is active and ever-changing. It can be performed in the future. It belongs to a time that is both gone and yet to come… This is not an archive of history but an affective archive of the present, past, and future. (113)

Perhaps one of the reasons why the participants in the Monstrous Weather netprov felt a need to adapt and re-perform the work could be, at least in part, due to an instinctive understanding that there is no way to accurately document or archive the experience of this type of performance, even when there is a clear, visible trace of the performance, such as the posts left behind in the public Google Group. It may be that the only way to capture the experience is to continuously revisit it, rewriting and retelling the stories that we had shared during the performance.

According to Rebei,“rewriting carries out two functions: one is that of writing the text again through a new inscription—thus remaking it and devising it anew, and the other is that of writing back to the original text” (47). By rewriting our experience of Monstrous Weather , by telling those stories over and over again, much as I am doing now by writing this paper about that process of rewriting and retelling, we were perhaps trying to carry out both of these functions, both making anew, and responding to the original text. But this raises another question: when does this process of repetition and rewriting come to an end, and reach closure? Perhaps, at some point, it is better to let the stories rest so that new stories can take their place. As Hight wrote in the penultimate posting in the netprov:

She deleted the story. It was a difficult decision, painful in fact, but it made sense.

She saw the future as it was to be, a gaping maw, a mouth of nothing with errant teeth of life and its chaos and breaking. She saw the way sun would rise over remains, over the reverberations of decisions of near present. She saw the ballast in the patterns emergent in her present, the poison waters of poor choices and ugly politics.

The future would need stories. It would need them in a way even she could not understand, the way of dermis, the way of keloid,

This story was not clear enough and others had said it in ways far more rich and clear so the delete button slid cursor ever back, to a nothing.

Acknowledgements

This research is funded under the National University of Singapore Humanities and Social Sciences Seed Fund grant “Communication Strategies in Real-time Computer-Mediated Creative Collaboration”.

Works Cited

Alley, Kathleen Marie. Playing in Trelis Weyr: Investigating Collaborative Practices in a Dragons of Pern Role-Play-Game Forum. University of South Florida, 2013.

Barthes, Roland. S/Z. Hill and Wang, 1974.

Berens, Kathii. Comment on “Occupying MLA.” 2013.

Bernstein, Mark. “Patterns of Hypertext.” Proceedings of Hypertext ‘98, ACM Press, 1998, pp. 21–29.

Calinescu, M. Rereading. Yale University Press, 1993.

Coover, Robert. Hypertext Hotel [Website]. 1994.

Hutcheon, Linda. A Theory of Adaptation. New York, Routledge, 2006.

Kartsaki, Eirini. Repetition in Performance. Palgrave Macmillan UK, 2017.

Kroeber, Karl. Retelling / Rereading: The Fate of Storytelling in Modern Times. Rutgers University Press, 1992.

Meanwhile… netprov studio. Monstrous Weather [Netprov]. 2016.

Mitchell, Alex, et al. “The Temporal Window: Explicit Representation of Future Actions in Improvisational Performances.” Proceedings of the 2017 ACM SIGCHI Conference on Creativity and Cognition - C&C ‘17, ACM, 2017, pp. 28–38.

Rebei, Marian. “A Different Kind of Circularity: From Writing and Reading to Rereading and Rewriting.” Revue LISA / LISA e-Journal, vol. II, no. 5, 2004, pp. 45–59.

Rettberg, Scott. “All Together Now: Collective Knowledge, Collective Narratives, and Architectures of Participation.” Proceedings of DAC 2005, 2005.

---. The Unknown [Website]. 1998.

Sawyer, R. Keith. Group Creativity: Music, Theater, Collaboration. Psychology Press, 2014.

Wittig, Rob. “Literature and Netprov in Social Media: A Travesty, or, in Defense of Pretension.” The Bloomsbury Handbook of Electronic Literature, Bloomsbury Academic, 2017.

---. “Pasts and Futures of Netprov.” Electronic Book Review, 2015, http://www.electronicbookreview.com/thread/electropoetics/netprov.

Wittig, Rob, and Mark C. Marino. “Occupying MLA.” The Chronicle of Higher Education, 2013.

---. OccupyMLA [Netprov]. 2011.

Cite this article

Mitchell, Alex. "Monstrous Weathered: Experiences from the Telling and Retelling of a Netprov" Electronic Book Review, 3 February 2019, https://doi.org/10.7273/rb6t-qz63