On "The Haunted House"

Keith Herber discusses how in his "Haunted House" scenario for Call of Cthulhu, characters are driven insane by their attempt to unravel the game's mysteries. Herber's explanation distinguishes his work from many other role-playing games in which the goal is to develop characters and acquire power and/or wealth. In contrast, characters in Herber's scenario are rewarded with mental instability.

The original Call of Cthulhu “Haunted House” scenario that appeared in the book Trail of Tsathoggua was written in 1983, when Call of Cthulhu was still a relatively new game and role-playing was still in its early stages. Seeing the light of day in 1981, Call of Cthulhu was unique to RPGs in that it didn’t rely on experience points, treasure, or other tangible rewards to induce players to participate. CoC investigators would not find hordes of gold or powerful weapons, nor would they gain fame or respect for their daring exploits. Quite the opposite, in fact. Investigators usually finish adventures in worse shape than they began, with less money, less sanity, and possibly a lowered social standing. Like cats, investigators are driven by curiosity, not by material gain.

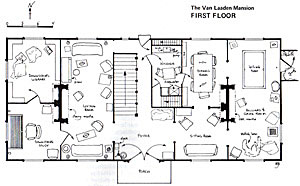

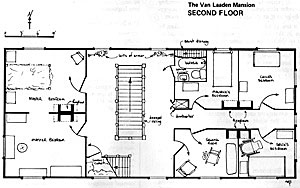

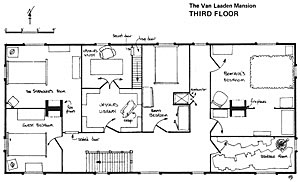

One of the concepts of “The Haunted House” was to expand upon the original Haunted House mini-adventure that has been included as part of the rules package since the game’s first printing. This one small scenario has done more to draw role-players to Call of Cthulhu than anything ever published for CoC, and I had the desire to exploit the concept to the max. By moving the idea to a very large house (a mansion typical of the Hollywood haunted house movie) every conceivable detail could be provided. Most CoC scenarios take place in towns, or open woods, or across several different locations. By necessity, not everything can be detailed, leaving it to the Keeper to be fast on his or her feet, and improvise information for curious investigators. “The Haunted House” was completely contained in one location, every room described in detail, every conceivable clue provided, and the scenario even included specific room - by - room suggestions about what the haunt might do to frighten investigators visiting a certain area. Unlike many CoC scenarios that tend to unfold of themselves regardless of player actions, the Haunted House is designed so the antagonist responds directly to player actions and little else.

I also wanted to create a scenario that avoided combat as much as possible. Prior to Call of Cthulhu, almost all RPGs were combat-oriented, as befitting a hobby with its roots in wargaming. But CoC offered something different, and the insidious Sanity rules were at the heart of that experience. Not only do investigators run the risk of being torn limb from limb, eviscerated, or swallowed whole, but may lose their minds as well. The whole underpinning of the game depends on the threat to one’s sanity, one’s sense of well-being and security.

While earlier games had invoked various saving throw rules to simulate fear or terror in a character, they were never very effective:

Gamemaster: “You open the door and see something awful. Make your Fear saving throw.”

Player: “I rolled a sixteen. I needed a fourteen or less.”

Gamemaster: “You’re so horrified by what you see, you can’t act.”

Player: “Oh, okay.”

The Sanity rules of Call of Cthulhu, on the other hand, manage to reflect the deteriorating sanity of many of the protagonists of the stories on which the game is based. Continued exploration of the Mythos tends to lower a player’s SAN rating, making it continually harder to maintain one’s sanity, leading to greater SAN losses, which it turn makes it harder to maintain control in the next sanity-threatening situation, and so on. It actually has a rather unsettling way of replicating real-life emotional problems and the way they feed upon themselves. It’s possibly the most effective and realistic set of rules ever created for a role-playing game. A player creeping around any CoC scenario who has a current SAN rating of 33 (or possibly less) is usually ready to jump out of his skin at the first sign of anything unusual. He knows he’s teetering on the brink of madness, and even a small shock may send him over the edge, leaving him permanently insane.

I wanted a scenario that threatened to drive investigators mad, rather than simply tearing them to pieces. I also wanted to see if I could create a scenario so difficult to unravel that most investigating parties would eventually give up and leave without solving the mystery, without destroying the haunt that inhabited the house. I wanted an adventure that would leave players with stories to tell. Best of all, it utilized the moral ambiguity inherent to Lovecraft and CoC. The haunt isn’t really bothering anyone - save the rich man who inherited the house. The investigators - who generally assume themselves to be “good” - are actually there to evict the supernatural tenant and will be paid money for destroying a creature who is actually bothering almost no one.

As a personal RPG philosophy, I believe that most players want to relive adventures and stories of the type they’ve read in books, or seen in movies or on television. Consequently, I’ve always made heavy use of established dramatic clichés, either presented straightforwardly or turned on their ear. Like any pop culture form of entertainment, you want a mix of the familiar combined with something new. I started the Haunted House design by making a list of all the spooky events I could remember from movies like Poltergeist, House on Haunted Hill, The Haunting of Hill House, and every other haunted house movie or story I could remember: flying knives, mysterious cold spots, chairs that rocked without an occupant, and anything else I could think of. I adapted some whole cloth, while others I reworked to either fit the situation or to put a new twist on them. Then I added ideas of my own. It was only after compiling this initial list that I gave any thought to creating the haunt’s powers, and then they were custom-designed to allow the haunt to create the effects I wanted.

The haunt was given powers and abilities that allowed it to terrify the investigators, and even inflict minor wounds, but for the most part kept it from actually killing or maiming anyone. Most of the creatures in the Call of Cthulhu world are exceptionally powerful and dangerous, and the Keeper needs be watchful he doesn’t overwhelm the players with Sanity losses, or wipe out the entire party in their first encounter. While earlier games followed the example set by Dungeons & Dragons, using an intricate rule balance to try to keep the players on a level footing with the challenges, the terrors of the Mythos are so overwhelming and powerful that a Keeper is required to use an uncommon amount of restraint, or run the risk of destroying the entire party on first encounter.

The haunt is far less dangerous than most Mythos creatures, and this allows the Keeper to settle into the scenario and actually play against the investigators on a more-or-less even playing field, utilizing the haunt’s resources to frustrate and terrify them, rather than simply destroying them. Although the haunt has a wide variety of powers to use against the investigators, they drain the creature’s power, which then must regenerate over a period of time. This requires the Keeper to refrain from simply hurling everything at the investigators at once. The most powerful effects not only drain the haunt completely, leaving it temporarily defenseless, but can also threaten the haunt’s own existence and so must be used with care.

The adventure abounds with red herrings. I included every possible haunted house cliché I could think of, most intended to lead the investigators down fruitless paths. There are numerous clues that point to the actual haunt, but the haunt is totally atypical, and the solution to the haunting doesn’t offer itself on a silver platter. Players generally keep coming back to one particular set of intriguing clues, but often don’t follow up on them as they get distracted by other red herrings that promise more straightforward solutions.

It’s a relatively benign scenario, intended to drive you mad, not kill you. In the several times I ran the adventure, no investigators were killed, nor were any driven permanently insane. At the same time, no one ever solved the adventure, or even came very close to a solution. All retired from the scenario, mostly unharmed, with a little less sanity than they began with, but almost all had good stories to tell the next few years.

Works Cited

“The Haunted House,” in Trail of Tsathoggua. Keith Herber; Chaosium. 1983.

Cite this article

Herber, Keith. "On "The Haunted House"" Electronic Book Review, 24 December 2007, https://electronicbookreview.com/publications/on-the-haunted-house/