REFLECTIONS ON & APPRECIATION OF A PILE FABRIC PRIMER

Scott Zieher offers some creative non-fiction in praise of perhaps Gaddis’s least-lauded publication: the lavishly illustrated and sample-provisioned “masterwork of printed ephemera” A Pile Fabric Primer. How did this mysterious document come to be, and what does it tell us about the creative writer's working conditions?

(Being an aleatory examination of the masterwork of printed ephemera edited by William Gaddis)

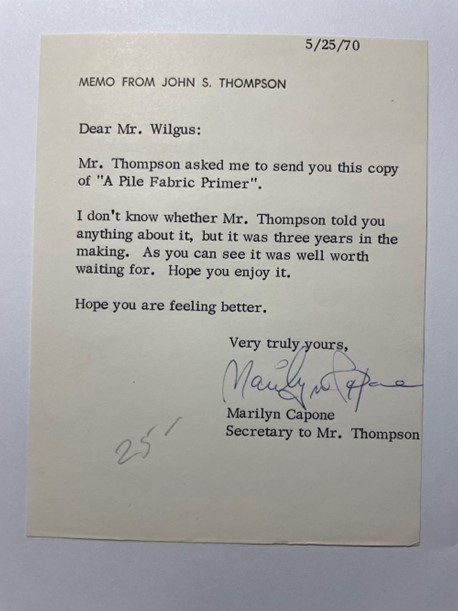

Gaddis, William and Mike Gladstone (eds.). A Pile Fabric Primer: Corduroy/Velveteen/Velvet. Crompton-Richmond Company, 1970. See Figure 1.

What are the chances Mr. John S. Thompson knew his three years in cahoots with Mr. Gaddis were three years rubbing elbows with America’s finest novelist, then, now, maybe for always? What are the chances Mr. Thompson’s elbows were covered in corduroys?

Could Mr. Wilgus have known who the editor might be of such an elaborate objet d’art as he sewed pillows for Sears Roebuck or curtains for middle management or trousers for already obsolete rock stars? Or was Mr. Wilgus just a middleman, selling his bulky bolts to the squab stuffer, the drapery cincher, or a seamstress for the band?

And what about Ms. Marilyn Capone? Did she thumb the sample swaths of velvet and imagine her unloving husband in a smoking jacket, pouring Riunite on ice to celebrate later that Monday night in late May? The high was 59 degrees in New York City that day, maybe he was stirring a hot toddy.

So many questions, probably not worth answering. Sometimes the questions are all that matter. Usually the answers are all too embarrassing.

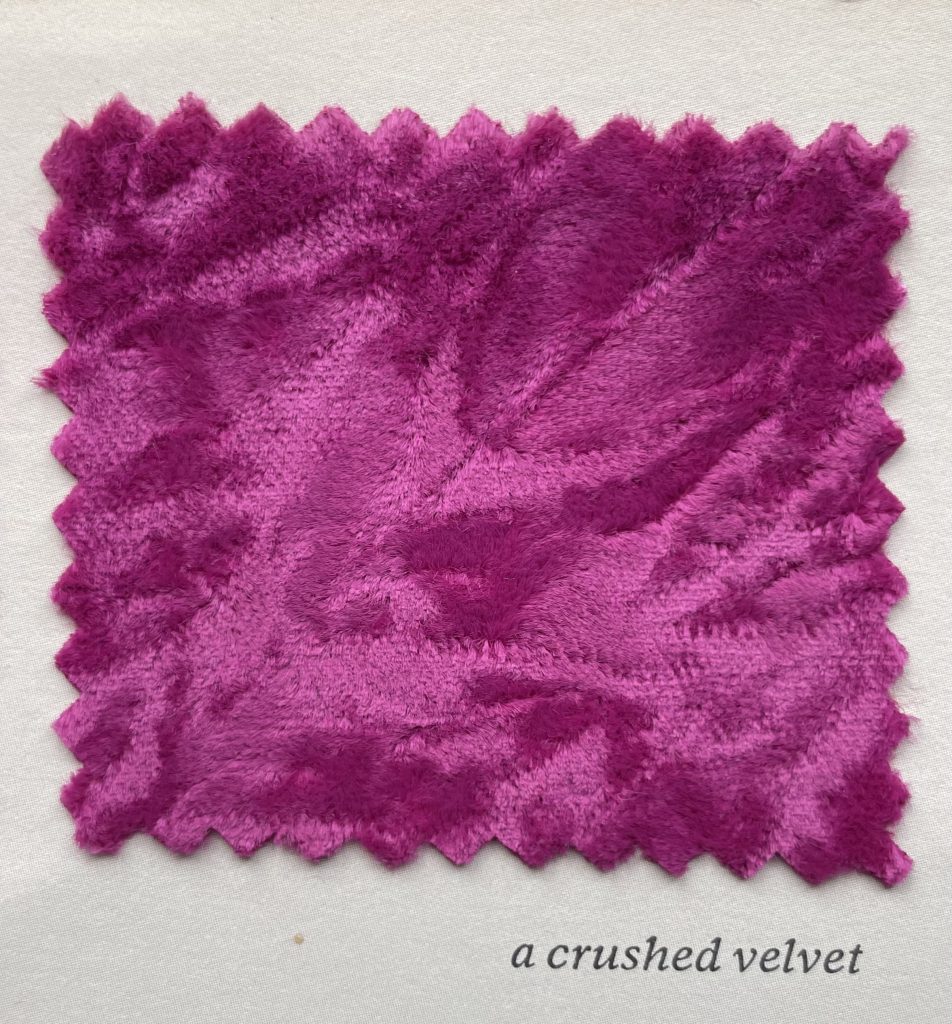

Weighing in at 56 pages with 37 fabric samples tipped in (see Figure 2), and including technical process illustrations dating back to 1900 B.C., this book was a sales gewgaw for Crompton Company, with mills in Griffin, Georgia, Raleigh, North Carolina, Waynesboro, West Virginia and Osceola and Morrilton, Arkansas, with sales headquartered at Crompton-Richmond and Hockmeyer Bros., in New York. Did our editor make site visits to learn the complicated trade? Was William Gaddis ever worrying over notes on pinwale and novelties, guide wires and warp ends, disgruntled over luncheon of pimento cheese sandwiches with house pickles and an Orange Fanta in Osceola?

Winston Potter might know. He designed this book (and is probably the reason it took three years, what with the half page interactive elements, and cover image permissions for Hyacinthe Rigaud’s “Louis XV as a Child” depicting the king surrounded by lush, thickset fabrics) as well as being the award winning designer of 1957’s Sociology for McGraw Hill. Crompton Mill Works still exists in Worcester, Massachusetts. But that’s all we know about Potter.

All across America that spring and summer of 1970 middle Americans were coasting through stale yellow lights in their late model chartreuse AMC Pacers, the wind whispering through their hair treatments; ignoring the world’s troubles, turning up Ray Stephens’s “Everything is Beautiful” on their newfangled FM radios. Meanwhile those lucky schmucks on the coasts gently maneuvered their outsized Oldsmobile Cutlasses into curbs with rotten rubber squeaks, turning down Edison Lighthouse’s “Love Grows (Where My Rosemary Goes)” just as it morphed into Bobby Sherman’s “Julie, Do Ya Love Me,” so as to better hear their wives asking if it would still be ladies night by the time they finally got to the supper club. All those sarcastic ladies’ hair couldn’t move in the whisper of wind because it had too much maximum hold Go Gay Hairspray.

And none of these players concerned themselves much with velveteen, velvets or corduroys.

I’ve long taken pride in owning A PILE FABRIC PRIMER and have now read it twice. Perusing it 53 years after its publication raises a host of weird questions.

First and foremost, why? Three years’ work for what amounts to a luxury fabric catalog masquerading as history (which could be a fascinating dissertation all its own). Was there a target audience for this labor of love? If so, who were these people? How many Americans could qualify as a market for such advanced guard ephemera?

Secondly, when the masthead refers to Gaddis as “editor,” does this not simply mean writer? Could there have been underlings doing the writing, with Gaddis simply red penciling redundancies and noun verb agreements, reordering paragraphs?

Joseph Tabbi did not find reason to include any portion of these three years’ work when editing Gaddis’s posthumous non-fiction collection The Rush for Second Place. In fact, none of the so-called corporate writings are included in that indispensable volume. Tabbi did, however, see fit to include a photograph of the covers of The Growth of American Industry and Answers to Cancer, neither of which are available on abebooks.com. It’s a handsome cover, Answers to Cancer, to be sure, but “by William Gaddis” might be the only thing that makes it more interesting than the tipped-in majesty of the manual for bespoke tuxedo haberdashers now under consideration. Maybe it’s the rhyming title. Yet the Primer rivals Gentry Magazine (a short lived men’s magazine of the 1950’s which often included fabric samples for the resort season set and seed samples for growing the best hay for your polo horse). Tabbi posits that the boy in the illustration from The Growth of American Industry—“a boy at a table with a Bible, a key, a pencil, and a voting ballot” (26)—could actually be a precursor to the young hero of J R. Maybe cancer and The Big Three are more important than textiles.

As a poet, I’ve learned little about writing from William Gaddis. He was Joe DiMaggio. I’m Joe Shlabotnik. However, as a reader, I’ve received a PhD in happenstance and good fortune through his guidance in absentia.

The men who introduced me to The Recognitions in 1987 are still my great friends nearly 40 years on. They still live on Scott Street in Milwaukee. That’s good luck as much as a queer coincidence.

My second time through The Recognitions I was living in New York and one Sunday began a chapter on the northbound 14th Street IRT subway station. That chapter miraculously took place in the very same train station. When I detrained I was in Central Park (it was a long wait) and the book followed suit; the next scene was in the zoo.

While I was reading A Frolic of His Own on a train from New York to New Orleans, I had a porter named Harry Lutz. I had the good fortune of meeting the maestro at the 1994 National Book Awards reading, the night before he won his second award and told him this story. He remembered a bit by Stendhal; that no matter how hard you work to create a character name that is out of the ordinary, there’s someone, somewhere waiting to sue you for it. There were times I couldn’t discern if I was following in my favorite writer’s footsteps or if it wasn’t (impossible) the other way around.

Respondeat superior, indeed.

It’s known that Gaddis worked corporate jobs to support his family, since the publishing world and reading public couldn’t seem to help him make ends meet on their own. As a poet, I always found this heartwarming. What I’ve been paid as a poet wouldn’t buy two rounds at Bemelmans. I wonder if the anonymous team who reupholstered the settees under Ludwig Bemelmans’s murals ever had a look at the Primer? I wonder if Gaddis ever hesitated, after a casual stroll through the Metropolitan while researching handy samples of his fabric subject on the gallery walls, to pick up the tab at Bemelmans one afternoon, his smoky hands quivering over a salver of Brazil nuts? Isn’t that what editors do?

All of my favorite books proffer questions that are impossible to answer. This one is no different.

It was likely Mike Gladstone who picked up the tab at the Carlyle that afternoon. Gladstone, who Gaddis met at Harvard and who Steven Moore’s notes to Gaddis’s Letters identify as a “lifelong friend” after that (229)—whose room, Moore then tells us, was the scene of the drunken binge that got Gaddis expelled from Harvard—had been a friend for decades by the late 1960’s, when Gladstone worked full-time in publishing, somehow acting as intermediary in this editorial job. Moore credits him, earlier in that decade, with introducing Gaddis to Judith, who would become his second wife (309). But though their friendship is public record, exactly how this collaboration on the Pile Fabric Primer came about remains mysterious. Gladstone’s name is more prominent on the title page than Gaddis’s. One can’t help but wonder if the task of editing this corporate miscellany was a favor dreamed up over drinks; Gladstone, the magazine and publishing impresario dropping a few crumbs for the genius toiling over his sophomore effort. Something to tide him over between drafts, perhaps? Or the kind of gesture that kept Gaddis from the plight of his friend David Markson (as spelled out in The Last Novel):

Another of Novelist’s economic-status epiphanies: Walking four or five blocks out of his way, and back, to save little more than nickels on some common household item.

In the end, the Primer proves to be reading as belabored as the production of its subject matter. Technical writing such as this book contains must have been tedious for a man writing what would become the masterpiece J R. If I were a used bookstore, the only place I could think of to shelve the lovely Primer tome would be behind glass. It doesn’t have a price (I paid $25.00 for my copy) and one can’t imagine the stipend it provided boiling very many pots, unless those pots contained turnips and onions. A sorrowful corollary comes in the poet Michael Gottlieb’s Jobs of the Poets:

So, how do we end up? Proofreading? Adjunct teaching? English as a Second Language? Construction? Bartending? Junior assistant odds-body? There was a time when some people got gigs writing pornography. You don’t hear much about that anymore, probably because it was, in fact, pretty hard work. Some folks did type setting, back when that was still a job. The apparent fact that these kinds of abnegation, this embrace of what some would call the ‘menial’ is a common or typical or credible option for us… what does that make us? Cleaner? Purer? Less compromised?

I’d say it fills our children’s bellies. James Joyce didn’t need to do this; he depended on handouts. Marcel Proust didn’t have to worry about such trifles. Markson just kept plugging, damning torpedoes the while.

This afternoon my five year old daughter asked me what a logo is. I pointed to the A for Atlanta Braves and the P for Philadelphia Phillies on my phone’s playoff radio feed. Then I pointed to the purple bovine cartoon of her Sweet Cow water bottle sticker, and then the young, curly haired Sun Maid on a raisin box and said, “logos are everywhere you look” and she asked, like any five year old should, “why?” And I said “because that’s how the world works anymore: branding” and she replied “boring.” Laughing in agreement, I wanted to remind her not to be a novelist, but I think she’s probably a dancer.

There was a rumor for awhile that William Gaddis was Thomas Pynchon. Thanks to Gaddis’s precedent, we can only imagine Pynchon never had to boil any pots whatsoever, but if so, it was probably pornography. We’ve all seen by now the photo that emerged of Pynchon, walking in New York City, holding his kid’s hand and carrying a depressing, disposable plastic bag full of common household items which he more than likely didn’t walk out of his way to purchase, saving nickels.

William Gaddis’s daughter, Sarah Gaddis published a novel in 1990 that’s difficult not to read as thinly veiled autobiography. A review of Swallow Hard by Laurel Graeber summarizes the plot thus: Rollin is the daughter of Lad, “an American writer of vast and difficult fictions” and Sally Ann “a pretty Southerner with no Europhile pretensions”:

The sound of Lad’s typewriter— an image of modern cultural brutality— dominates the household. Wreathed in cigarette smoke, he sits at it, obsessed and unresponsive, while Sally Ann is patronized by his friends and assaulted on the New York streets. After a decade or so, her patience exhausted, she leaves him for a more decent chap. And thus Rollin becomes a princess in exile among limited minds. Her mother’s new man goes in for boring hikes and tasteless décor; soon a mess of half siblings appears, and for Rollin it’s all too clear: “Her mother had chosen the wrong life.”

The character of Douglas, Lad’s wealthy classmate from Harvard and Rollin’s godfather, might well be a stand-in for Mike Gladstone. Possibly just wishful thinking, but still enticing.

There’s a murder, some intrigue, and the curious bequest of an artist’s colony by the millionaire godfather to the young woman and “then the Department of Transportation claims the property for a new road.” It’s Gaddis’s world, we just live in it.

The jacket photo of Sarah Gaddis poses her with her right hand at a slight remove, on a chair, apparently upholstered in velvet. Even embittered and alienated, it appears that genius is preferable to comfort. Not every child of a creative sort needs to suffer, but maybe their fathers need to labor over things most people choose to ignore.

Cite this essay

Zieher, Scott. "REFLECTIONS ON & APPRECIATION OF A PILE FABRIC PRIMER" Electronic Book Review, 5 May 2024, https://doi.org/10.7273/ebr-gadcent6-6