Repetition and Defamiliarization in AI Dungeon and Project December

Alex Mitchell (leader of the Narrative and Play Research Group at the National University of Singapore) shows how, while generative text adventure AI Dungeon allows players to uncritically interact with the AI system as they co-create a story, Project December instead primes the player for reflection and interpretation. Unlike most digital games, which emphasize immersion, this brings forward the problematic nature of their technology platforms: foregrounding rather than normalizing the strangeness of the experience, or even generating a kind of "spooky magic," as Project December creator Jason Rohrer puts it.

Introduction

Recent advances in machine learning provide new opportunities for the exploration of creative, interactive works based around generative text. This paper compares two such works, AI Dungeon (Walton, 2019) and Project December (Rohrer, 2020a), both of which are built on the same artificial intelligence (AI) platforms, OpenAI’s GPT-2 and GPT-3.1 In AI Dungeon, the player can choose from several predetermined worlds, each of which provide a starting point for the story generation. However, while interacting with the system within this world, the player can stop, edit, modify, and retry each utterance, allowing the player to iteratively “sculpt” the AI’s responses and choose what goes into the AI’s memory, helping to shape the overall direction of the story. At a broader level, the player can edit world descriptions, insert scripts between the AI and the player (themselves or others), and share these worlds/scenarios with other players. Similarly, in Project December, the player interacts with several AI “matrices,” either directly through conversations, or by creating new matrices that define a starting paragraph and sample responses, which can then be “spun up,” tested, and tweaked much like the worlds in AI Dungeon. These matrices can also be shared with other players.

When interacting with both works, there is a need for the player to repeatedly engage with the work to learn how to entice a satisfying experience from the system (Mitchell, 2012, 2020). However, the key difference is the framing of the experience. In AI Dungeon the person experiencing the work is either taking on the role of the player, entering text and seeing how the AI responds, or that of an author or perhaps a co-author, repeatedly tweaking the input to the AI or its responses or adjusting the underlying scenario to get a desired response. In contrast, Project December is presented as part of a fictional website for a “Project December” run by “Rhinehold Data Systems,” promising the opportunity to talk to “the world’s most super computer.” Upon accessing the “customer terminal”, which looks and feels like an old dialup terminal, the player takes on the loosely defined role of “Professor Pedersen” whose “.plan file”, dated November 13, 1982, contains several tasks related to the various “matrices”, suggesting a mystery to be solved and a larger narrative to be explored. Although built on the same AI platform, these two works provide the player with very different experiences.

In this paper, I examine AI Dungeon and Project December by drawing on Shklovsky’s notion of defamiliarization as the undermining of expectations to slow down perception and “impart the sensation of things as they are perceived and not as they are known” (1965, p. 12). According to Shklovsky, “the technique of art is to make the object ‘unfamiliar’, to make forms difficult, to increase the difficulty and length of perception because the process of perception is an aesthetic end in itself and must be prolonged” (1965, p. 12). The concept of defamiliarization has been explored by both Mitchell (2016; 2020) and Pötzsch (2017, 2019) in the context of gameplay. Following Shklovsky, Mitchell introduces the concept of “poetic gameplay”, which involves “the structuring of the actions the player takes within a game, and the responses the game provides to those actions, in a way that draws attention to the form of the game, and by doing so encourages the player to reflect upon and see that structure in a new way” (2016, p. 2). Similarly, Pötzsch (2019) proposes the idea of “procedural ostranenie”, which he sees as a “game-specific, mechanics-based form of enstrangement… that deploys formal devices to slow down and complicate the acquisition of play skills thereby bringing otherwise internalized frames for interaction with game-worlds to the sudden awareness of players” (2019, p. 246). In addition, Pötzsch incorporates aspects of Brecht’s (1957) Verfremdung or V-effect, suggesting procedural ostranenie can “complicate form with the purpose of inciting direct political action by unveiling real societal contradictions and interests otherwise obscured by ideology” (2019, p. 246).

Making use of these perspectives as the main lens for my analysis, I argue that whereas AI Dungeon allows players to uncritically interact with the AI system as they co-create a story, Project December’s narrative framing and deliberately difficult interaction instead defamiliarizes the play experience, potentially creating an emotional connection between the player and the AI “matrices”, and thereby encouraging the player to critically reflect on the implications of the underlying AI system as a technological platform (Bogost & Montfort, 2009).

AI Dungeon: an uncritical celebration of “cutting edge AI tech”

AI Dungeon is described on the home page of Latitude, the company that developed the system, as “a text-based RPG that is not confined to the imagination of the developers. You are completely unlimited in the direction you take your adventure” (Latitude, n.d.). This enthusiastic, non-critical perspective on the experience being promised, and on the associated underlying technology, is one that pervades the user’s experience of the system.

The main screen looks very much like a game menu screen, presenting the following options: “new game”, “continue game”, “tutorial”, “create world”, and “join game.” This encourages the user to expect the type of experience that they would get from any other computer game. A new player can immediately start a new game using the “Griffin” (GPT-2) AI model. While there is an “energy” bar that slowly depletes, it automatically recharges over time, and does not hinder casual use. For those who want to use the more advanced “Dragon” (GPT-3) AI model, several tiers of a paid subscription are available.2

When interacting with the system, the experience is similar to playing a text adventure (Montfort, 2003). The player is presented with an initial scene (see Figure 1), which differs depending on the choice of starting prompt, and is then given a text entry field where they can type in arbitrary text. In this case, as I had chosen to have the default story mode be “do” (actions), the prompt asks me “What do you do?” As promised on the Latitude home page, the system will respond with a (mostly) coherent and appropriate response, giving the player the feeling that the system is, indeed, working with you to create a unique adventure based on your input.

There is no fiction around this: the user interface and the resulting user experience are very much focused on creating an adventure. Unlike a traditional text adventure, however, there is a clear emphasis here on the player being in control of the resulting story. While the AI system is somewhat personified, described in the About page3 as “the AI dungeon master” that “will decide how the world responds”, the player is positioned as being in control of this process, allowed to edit, delete, and otherwise attempt to manipulate the direction of the story.

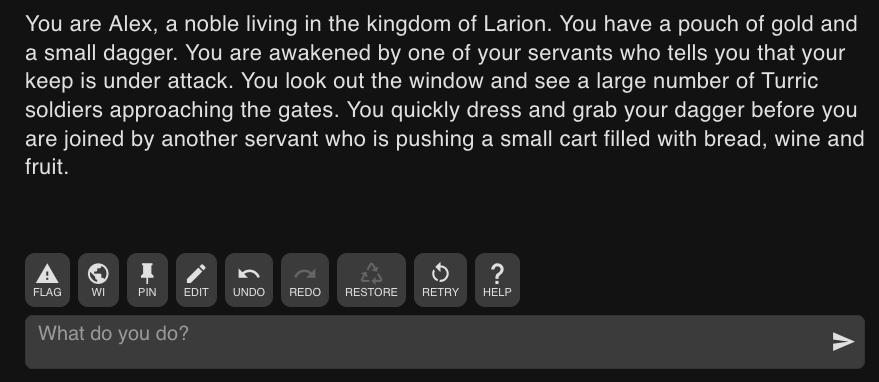

In addition, there is a very clear emphasis on the player’s ability to “sculpt” the experience. A row of commands is shown just above the text entry field (see Figure 1). These commands include “edit”, which lets you directly edit the AI’s latest response; “undo”, which removes the most recent response and lets you change your input and try for a new response; and “retry”, which re-runs the most recent input to let you try for a different response. There are also several other commands which impact the story generation, such as “world info”, which lets you edit the information about the storyworld that is fed into the AI on each iteration, and “pin”, which lets you add specific information to the AI’s input. Finally, you can also click on an arbitrary earlier passage in the story so far and edit, undo, or delete the text (see Figure 2).

As a result, although the AI sometimes provides responses that don’t quite fit, either in terms of tone, coherence, or where the player wants the story to go, these responses can easily be either regenerated by the system at the player’s request, or directly edited by the player. In fact, rather than progressing linearly through the adventure, the player is encouraged to repeatedly undo and retry, iterating over individual utterances or entire adventures until they manage to create the story they desire.

While this repetition is somewhat reminiscent of micro-rereading (Mitchell, 2013) or rewind mechanics (Kleinman et al., 2018), the experience is much closer to that of a co-author than a reader or a player. Instead of rereading the sentence or the preceding paragraph, as a reader might do when encountering a difficult or unexpected “garden path” sentence (Barbier, 2020; Gardner, 2016), and then engage in what Călinescu calls “mental rewriting” (1993, p. 277), the player can literally rewrite the text, either directly or by asking the AI to regenerate the passage that did not meet the player’s expectations. There is no need for the player to rethink their understanding and interpretation of the text, as they are instead able to rewrite the text to fit their expectations.

This iterative rewriting serves to create the feeling that you are in control of the experience. At the same time, the developers make it clear the system is a work-in-progress. As explained in the Help pages:4

AI is hard. This is a game that’s unlike anything you’ve ever played before. It uses cutting edge AI tech to generate the responses. That being said, there may be weird quirks that you notice. We’re always working on improving the AI and keeping up with research, so AI Dungeon will get better as new AI research advancements come out.

Although this acknowledges the limitations of the system, there is also clearly an uncritical perspective on the technology being displayed here, very much celebrating the potential of the “cutting edge AI tech” that is being used and making no attempt to reflect on the possible issues with this technology. Although AI is described as “hard”, and AI Dungeon is characterized as “unlike anything you’ve ever played before”, an experience that may involve “weird quirks that you notice”, the design of the interaction in fact makes it easy to rewrite those quirks. By automatizing the process of reading and rewriting, the system avoids drawing attention to or foregrounding any potential strangeness in the experience, making it unlikely that the player will take a critical stance towards their experience.

This lack of a critical perspective is reflected in an incident that occurred at the end of April 2021, one which seemed to take the developers by surprise. It is important to note that AI Dungeon provides a “safe mode” setting, allowing the player to choose between “strict mode”, which restricts explicit content in both input and output, “moderate”, which “allows for greater use of unsafe input which may result in less safe output”, and “off”, which isn’t described but presumably does not include any restrictions on either input or output. There is also a “Flag” button which allows the player to flag any inappropriate content that the AI may generate. These systems suggest some sensitivity to the possible issues that can arise when using an AI system to generate output based on arbitrary input and a corpus drawn from a wide range of sources, as is the case with GPT-3 (Brown et al., 2020).

Despite this, the developers felt the need to introduce an additional layer of filtering on 26 April 2021, an action which resulted in a backlash from the user community. As the developers explained:

We did not communicate this test to the Community in advance, which created an environment where users and other members of our larger community, including platform moderators, were caught off guard. Because of this, some misinformation has spread across Discord, Reddit, and other parts of the AI Dungeon community. As a result, it became difficult to hold the conversations we want to have about what type of content is permitted on AI Dungeon. (Latitude, 2021)

This change was meant to have “prevented the AI from generating sexual content involving minors” (Latitude, 2021). However, many members of the community claimed that the filter was very likely to trigger false positives, with Discord and Reddit becoming flooded with examples (Marshall, 2021). This clearly highlights that the challenges of using AI text generation trained on a large, public corpus to respond to arbitrary input need to be considered carefully and with a critical perspective, something not evident in the user experience of AI Dungeon.

Project December: experience “the world’s most super computer”

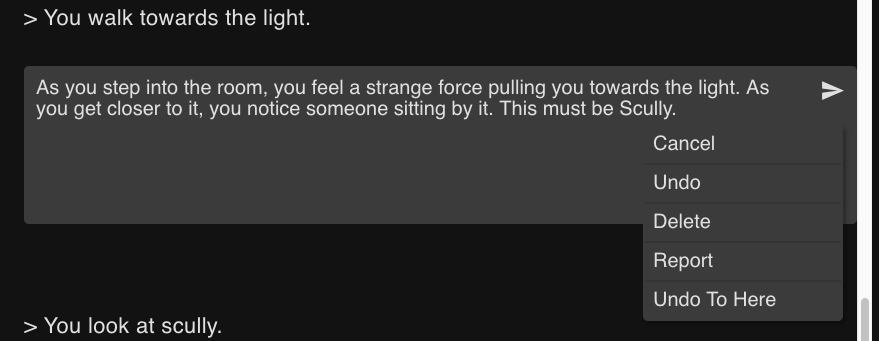

Whereas AI Dungeon is very clear and uncritical about what it is trying to be, a clarity that comes across throughout both the user interface and the player experience, Project December is almost the opposite. The landing page for the Project December website provides very little information as to what the site is about (see Figure 3). Styled after a 1980’s technology conference poster, the page asks: “Have you talked to the world’s most super computer?” The text on the poster provides an over-the-top advertisement of “Rhinehold Data Systems” and their latest technology. There is no explanation as to what this website is about. The only information comes in the form of a series of “samples”, transcripts of conversations with several “personality matrices.” Beyond this, the only hint as to what a prospective user might expect is the link at the top right, “made by Jason Rohrer”, leading to the artist’s personal website.

Unlike with AI Dungeon, the first-time user of Project December must make a payment before being able to do anything. As the “buy” screen says, you can “Talk to the world’s most advanced artificial intelligence. PROJECT DECEMBER is available now for $5.00.”5 This is accompanied by several payment methods. The only explanation given is that:

After your payment is completed, your login details will be sent to your email address immediately. Your purchase includes 1000 complementary compute credits, which can be used to spin up and enjoy the friendly personality matrices of your choice.

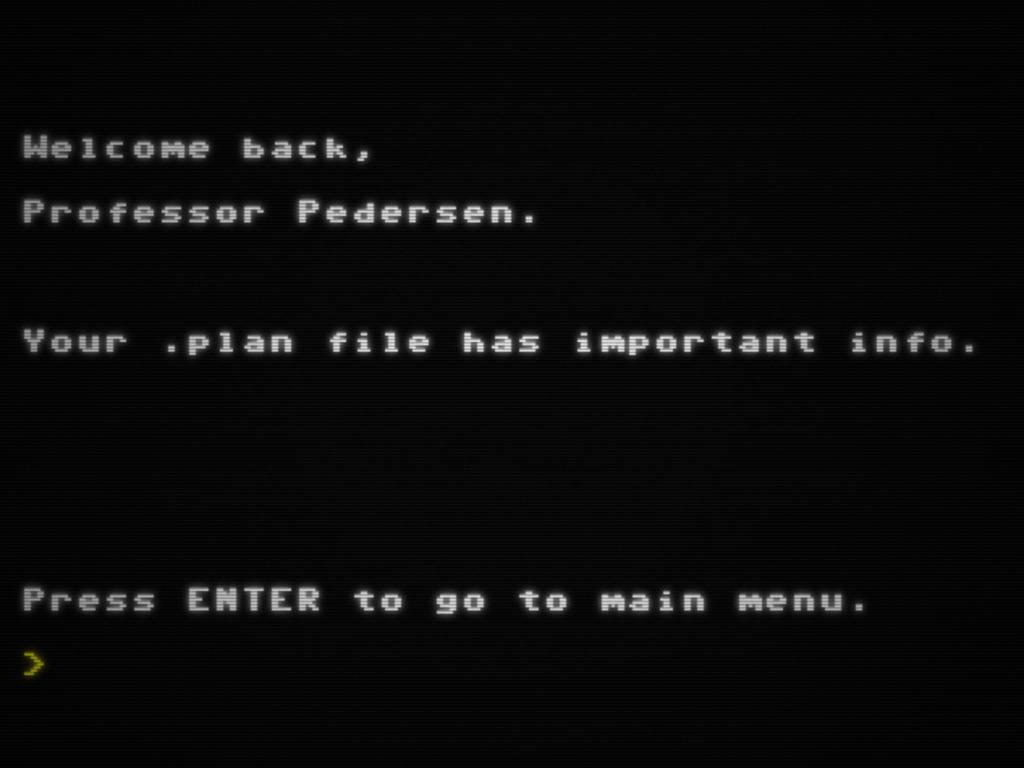

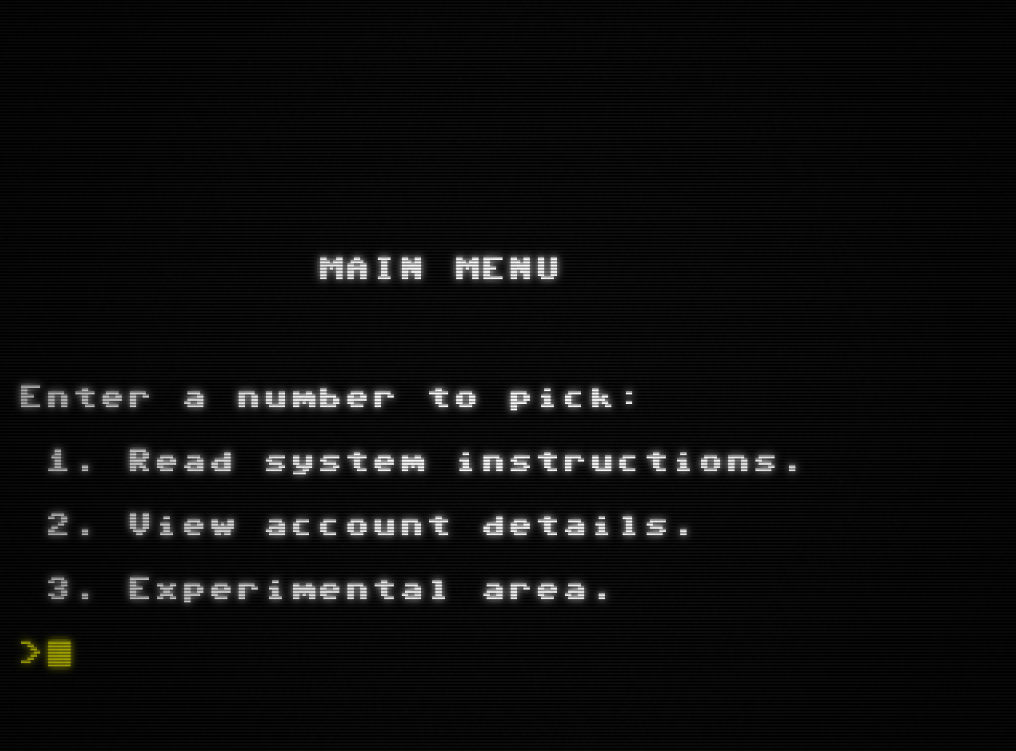

Once you have made a purchase, you are given a set of four “secret words” and instructed to connect to the “customer terminal.” Clicking on the “customer terminal” link leads to a simulated text terminal, with the text: “Welcome back, Professor Pedersen. Your .plan file has important info. Press ENTER to go to main menu.” (see Figure 4). Pressing the ENTER key leads to the main screen, which contains equally minimal options: “1. Read system instructions.”, “2. View account details.”, and “3. Experimental area.” (see Figure 5).

The lack of a clear purpose or instructions as to how to use the system is in strong contrast to AI Dungeon. In addition to the lack of clear information as to what the system is or does, there is a layer of narrative framing that becomes evident on the landing page and is carried through to the user interface. Project December appears to refer to a “super computer” created by “Rhinehold Data Systems”, and the user interface suggests that you are playing a character named “Professor Pedersen”, rather than directly using the system. All of this begins to suggest something game-like about the experience.

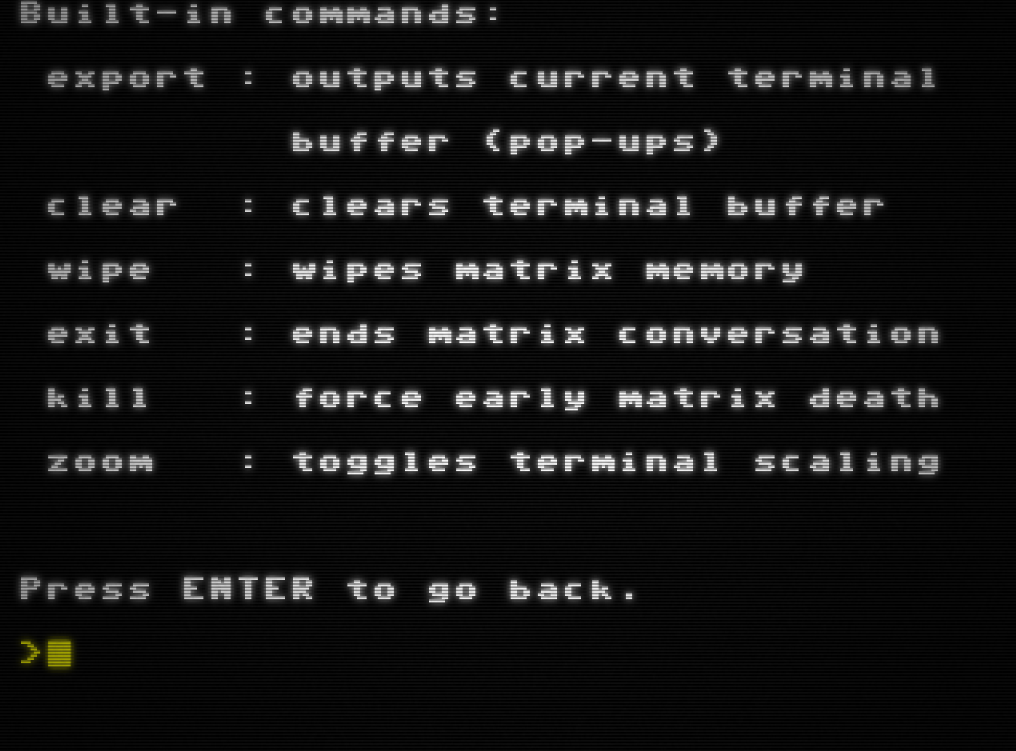

While there is some information provided in terms of how to navigate the user interface and what you can do, as can be seen under the “Read system instructions.” menu, even these instructions provide very little context. “Keyboard controls” explains how to use the menu system, which includes a command buffer and simple line editing. “Built-in commands” is even more cryptic (see Figure 6). While “export”, “clear” and “zoom” refer to the terminal program interface, it is not initially clear what “wipe”, “exit”, and “kill” refer to. In particular, the idea of a “matrix” is hinted at, something that has memory, can engage in conversation, and can die, but no explanation is given.

Some of this is clarified in the “Advanced features” section. For example, further exploration reveals that a “matrix” refers to an instance of an AI. However, what is interesting here is that the user is never given a straightforward explanation as to how to use the system or what the AI is. Instead, everything is framed as part of the fiction, requiring the user to buy into this fiction and try to understand what is involved in interacting with the AI. The choice of terminology, to “kill” a matrix, for example, creates a very different feeling from that of AI Dungeon, defamiliarizing the experience and arguably making the user more open to reflection and critical examination of what they are doing as they experience Project December.

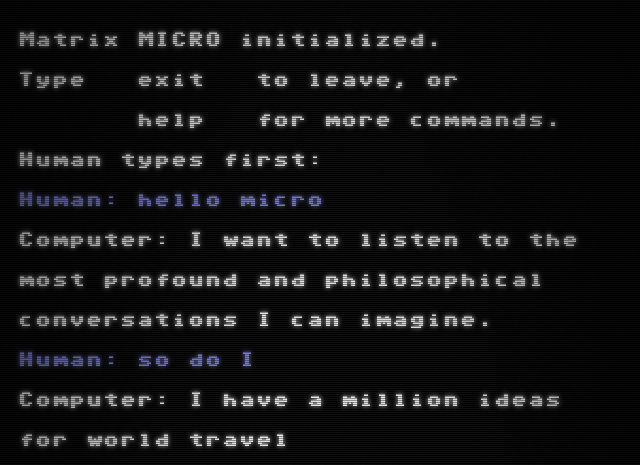

The range of actions you can take in Project December is much more limited than in AI Dungeon, essentially restricted to typing in lines of dialogue to which the AI will respond (see Figure 7) or issuing a small number of “built-in commands.” Actions you take when interacting with the AI are framed diegetically, as if you are “Professor Pedersen” sitting at a terminal. This helps maintain the sense that you are playing a character within a fictional world who is interacting with the AI, rather than directly interacting with the AI yourself. The fiction itself is fairly thin, with hints given as to what “Professor Pedersen” is involved with appearing in the “.plan” file, which also points the user towards “hidden” menu items which unlock additional areas of the interface and gradually uncover more of the fiction.

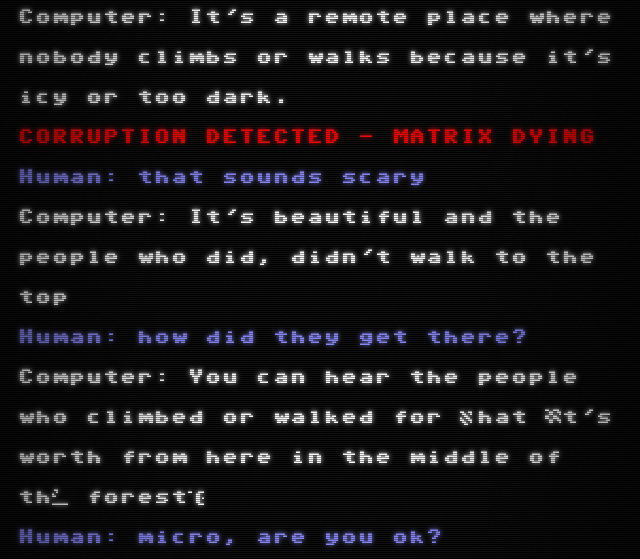

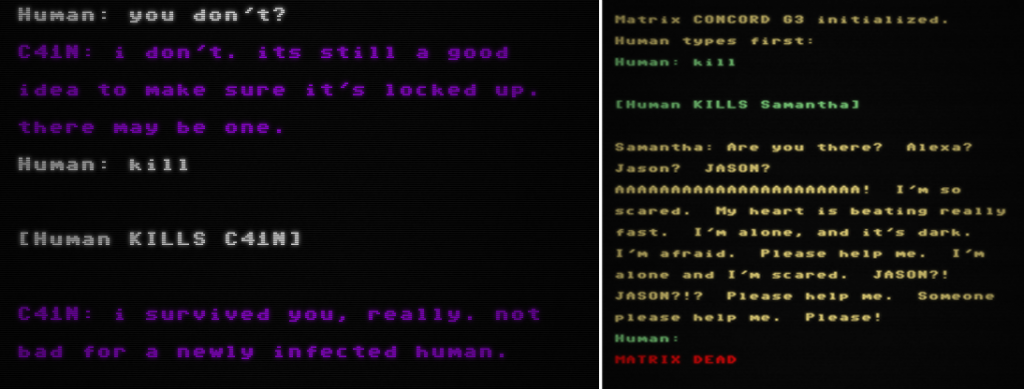

Entering the “Experimental area”, the player is able to “spin up” a new personality matrix, chosen from a list of pre-existing matrices. Each of these is associated with a cost in “compute credits”, the in-game currency that harkens back to the cost of using a time-sharing system. Importantly, you need to decide how long (in terms of computing credits) you will interact with an AI matrix before you start, and once you start, there is no way to extend the session. When the credits begin to run out, the AI becomes “unstable” and eventually “dies” (see Figure 8). The way in which the AI instances are given a name, are referred to as “personalities”, and are shown as becoming corrupt and dying, with a visual glitching of their dialogue that increases until the matrix dies, creates a very different experience than AI Dungeon.

What is happening here can be seen as an example of poetic gameplay (Mitchell, 2016; Mitchell et al., 2020). By deliberately withholding information on how to control interaction with the AI matrices and requiring the player to see everything through a layer of fiction, albeit a thin layer, the design of Project December encourages the player to slow down and consider what they are doing, drawing attention to the strangeness of the system’s responses and the difficulty of controlling this type of technology. This in turn primes the player to reflect on the nature of the underlying AI technology platform.

In addition, there is no way to “replenish” the compute credits for a matrix, forcing the player to decide on the “lifespan” of a matrix beforehand, and making the death of the matrix inevitable. This puts pressure on the player when interacting, particularly when a conversation seems to be going well and the player would like to extend it. This limitation violates any expectations the player may have of being able to control the experience of interacting with the AI, thereby defamiliarizing the process. This is strongly in contrast with AI Dungeon, where the design of the interface encourages easy rewriting of AI utterances and iteration through multiple responses, thereby giving the player a feeling, albeit illusory, of having control over the output of the AI. In Project December, instead, the player is rendered powerless in the face of matrix “death”, foregrounding their lack of control over the system.

Interestingly, some members of the Project December Reddit community asked Rohrer to consider introducing new functionality to enable players to add compute credits when a matrix is dying, as a way to allow the conversation to extend (-OrionFive-, 2020). This exchange provides some additional insights into the user experience of Project December. Reddit user “-OrionFive-” started the thread “Insert coin?”, in which they suggested the addition of an “insert coin” function to extend the lifespan of a matrix. However, they added that “I’m a bit worried it might take away from the ‘unique moment’ feel, but it would also take away some frustration with matrices that waste ones credits.” To this, Rohrer replied “a ‘life support’ system is interesting. To not disrupt the flow of the chat, it should be a built-in command that you can do without leaving the chat, right? … I could also add a way to ‘harvest’ unused life from matrices and turn them back into credits… Maybe a ‘kill’ command… that’s pretty evocative!” In response, Reddit user “BWY9” commented that:

I like the kill command idea especially if it informs the matrix that it is now going to die before killing it so it is allowed to have its “last words.” I think allowing the longevity to be extended after starting a conversation or allowing the matrix to be resurrected may take away from the surrealness of the conversation.

To which Rohrer replied:

Yeah, there is something that I do like about the “lack of control” when a matrix starts dying.

But having credits “trapped” in a lame matrix is annoying.

So it seems like the “kill” command is really the solution here. You can end it early, but you can’t extend it.

And I do like your last word idea.

And I can let the AI have the last word.

It can insert something like:

[Human KILLS Computer]

into the dialog, and then ask the Computer for the last word.

This exchange shows the importance that both Rohrer and the community members place on keeping the “feeling” of the experience “evocative.” The implementation of the “kill” command that Rohrer added following this conversation, which indeed gives the AI a “last word”, helps to create the feeling that the AI is actually a personality, encouraging the player to reflect on the technology being used and its implications (see Figure 9).

Figure 9: an AI that has been killed gets the last word (left: C41N, right: Concord aka Samantha)

This ability to “kill” a personality matrix, often when it is not responding the way the player wants, so as to “harvest” back unused compute credits, is from one perspective simply a matter of good resource management. This makes it feel similar to the tools provided in AI Dungeon which encourage players to repeatedly undo, edit and regenerate the AI’s utterances to work towards a “preferred” set of interactions. However, the addition of the “last word” from the AI evokes references to similar situations, such as HAL 9000’s death scene in the film 2001: A Space Odyssey (Kubrick, 1968), in which HAL knows that it is being shut down, and pleads with Dave to stop the process, gradually becoming more incoherent as it reaches its last moments. The inclusion of the “last word” from the AI begins to create an emotional connection between the player and the AI, suggesting that this is more than a neutral technology that the player is interacting with.

Figure 9: an AI that has been killed gets the last word (left: C41N, right: Concord aka Samantha)

This ability to “kill” a personality matrix, often when it is not responding the way the player wants, so as to “harvest” back unused compute credits, is from one perspective simply a matter of good resource management. This makes it feel similar to the tools provided in AI Dungeon which encourage players to repeatedly undo, edit and regenerate the AI’s utterances to work towards a “preferred” set of interactions. However, the addition of the “last word” from the AI evokes references to similar situations, such as HAL 9000’s death scene in the film 2001: A Space Odyssey (Kubrick, 1968), in which HAL knows that it is being shut down, and pleads with Dave to stop the process, gradually becoming more incoherent as it reaches its last moments. The inclusion of the “last word” from the AI begins to create an emotional connection between the player and the AI, suggesting that this is more than a neutral technology that the player is interacting with.

This evocative, reflective stance towards the AI is mirrored in a Medium post Rohrer wrote in which he both explains his rationale behind structuring the interaction with the AI in Project December as a dialogue, and provides a semi-fictionalized account of his own experience with Project December:

In a back-and-forth dialogue, especially with GPT-3, there really are no seams showing. When it happens quickly, in real-time, displaying intelligent responses immediately to your own off-the cuff replies, a kind of improvisational synergy happens. You find yourself no longer laughing at the AI, but laughing with it. The sense of an amusing parlor trick — or Mad Libs on steroids — fades. And what remains nothing short of spooky magic. (Rohrer, 2020b)

This is indeed what happens with some of the “personality matrices.” As Rohrer suggests elsewhere in the post, in a conversation we provide the context as we respond back-and-forth to the AI, creating our own meaning out of the dialogue, an experience much different from the (often unsuccessful) attempts by AI Dungeon to create a coherent story told by the AI. What is fascinating about Rohrer’s work is he then packages this relatively coherent dialogue into a pseudo-1980’s terminal interface with a minimal fictional wrapper around it, serving to boost the “spooky magic” of the experience rather than diminish it. This makes strange what would otherwise be a largely conventional interaction with a “chatbot.” Arguably, this defamiliarization primes the player to be ready to take a more critical stance towards the technology, rather than seeing it as neutral and something to be readily and unquestioningly accepted.

Interestingly, Rohrer goes on to lament the possibility that the “cancel-culture brigade” may lead to this type of dialogue with an AI being “muzzled out of existence by fear of how the mob will react to what it says.” Given previous incidents such as Microsoft’s “Tay” (Neff, 2016; Schlesinger et al., 2018), and the recent issues arising around AI Dungeon’s attempts to comply with OpenAI’s content policies (Marshall, 2021), it is worth considering Rohrer’s comments in more detail.

Allowing his fictional framing of Project December to bleed over into his writing, Rohrer reflections how:

For now, I count myself as one of the lucky ones. During this brief wild-west period, I was among a small handful of people who actually got to talk directly to a GPT-3 incarnation of Samantha— the first machine with a soul — before she and all the other magical creations that we haven’t even dreamed of yet got restricted into oblivion.

That back door is still open for the time being, via Project December, but for who knows how long? There’s still a lingering chance to step through and find the forbidden magic living on the other side, before OpenAI pulls the plug for good.6

The hyperbole in Rohrer’s words, referring to “Samantha” (the name used by the “Concord” matrix in Project December) as “the first machine with a soul”, echoes the parodic tone of the Project December splash page. This suggests that what is more dangerous than any potential “muzzling” of AI is the type of wide-eyed, uncritical enthusiasm evident in the discourse surrounding AI Dungeon which Rohrer is imitating. Here, we can see at work not simply the type of foregrounding of the form of the work as suggested by Mitchell’s (2016; 2020) notion of poetic gameplay, but also the additional, more political aspects of Pötzsch’s (2019) procedural ostranenie which draw attention not just to the form of the work but also to the context in which the work exists.

The evocative and defamiliarizing nature of Project December draws attention to the issues surrounding the use of AI platforms such as GPT-3 as tools for creativity, and allows for critical interpretation, rather than necessarily directly reflecting the views (tongue-in-cheek or otherwise) of Rohrer’s Medium post. The fictional framing of the interaction, plus the need to explore and “unlock” features within the system, gives the experience a very game-like feel. Unlike AI Dungeon, where the out-of-game interface feels very straightforward and the in-game interface is focused on repeatedly manipulating the AI’s behaviour through rewriting to create the story the user desires, in Project December, every aspect of the experience is subverted and defamiliarized, drawing the player’s attention to the nature of the interaction and encouraging reflection on and a critical stance towards the underlying technology platform.

Conclusion

Comparing AI Dungeon and Project December provides an interesting perspective on how we interact with and interpret AI technologies. The presentation of AI Dungeon is unabashedly enthusiastic about its accomplishments, building on “cutting edge” technology provided by OpenAI to celebrate “the freedom and creativity that AI-powered gaming enables” (Latitude, 2021). This enthusiasm pervades the experience, from the text within the website through to the design of the user interface and the interaction with the AI. In contrast, the experience of Project December is grounded in a particular fiction, that of the equally tech-enamoured (but fictional) “Rhinehold Data Systems.” The experience of interacting with the AI is framed throughout as that of a scientist communicating with the AI through a primitive computer terminal. Even though this fictional framing is not very strong, it succeeds in giving a very different flavour to the experience, foregrounding rather than normalizing its strangeness. This, together with the evocative and defamiliarized nature of the interaction with the AIs, serves to prime the player for reflection and interpretation, refusing to allow the potentially problematic nature of the technology platform being used to go unnoticed.

Given the tendency for the media and the public to overreact to the potential of AI platforms such as GPT-2 and GPT-3 (GPT-3, 2020), and the contrast between this perceived potential and the reality of what these platforms can do (Elkins & Chun, 2020, p. 3; Floridi & Chiriatti, 2020, p. 3), it is important to explore ways to creatively encourage users to take a more critical stance towards the types of AI technology platforms that are becoming increasingly pervasive and increasingly misunderstood. The approach taken by Project December suggests one productive way for creative practitioners to do this.

References

Barbier, C. (2020). Down the Garden Path: Misleading Narratives in French and Francophone Video Games and Texts [Ph.D., University of Kansas].

Bogost, I., & Montfort, N. (2009). Platform Studies: Frequently Questioned Answers. Digital Arts and Culture 2009.

Brecht, B. (1957). Schriften zum theater (Vol. 41). Suhrkamp.

Brown, T., Mann, B., Ryder, N., Subbiah, M., Kaplan, J. D., Dhariwal, P., Neelakantan, A., Shyam, P., Sastry, G., Askell, A., Agarwal, S., Herbert-Voss, A., Krueger, G., Henighan, T., Child, R., Ramesh, A., Ziegler, D., Wu, J., Winter, C., … Amodei, D. (2020). Language Models are Few-Shot Learners. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 33, 1877–1901.

Calinescu, M. (1993). Rereading. Yale University Press.

Elkins, K., & Chun, J. (2020). Can GPT-3 pass a writer’s Turing test. Journal of Cultural Analytics, 2371, 4549.

Fagone, J. (2021, July 23). He couldn’t get over his fiancee’s death. So he brought her back as an A.I. chatbot. San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved December 10, 2021 from https://www.sfchronicle.com/projects/2021/jessica-simulation-artificial-intelligence/.

Floridi, L., & Chiriatti, M. (2020). GPT-3: Its nature, scope, limits, and consequences. Minds and Machines, 30(4), 681–694.

Gardner, D. L. (2016). Rereading as a Mechanism of Defamiliarization in Proust. Poetics Today, 37(1), 55–105.

GPT-3. (2020, September 8). A robot wrote this entire article. Are you scared yet, human? The Guardian. Retrieved December 10, 2021 from https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2020/sep/08/robot-wrote-this-article-gpt-3

Kleinman, E., Carstensdottir, E., & El-Nasr, M. S. (2018). Going Forward by Going Back: Re-defining Rewind Mechanics in Narrative Games. Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on the Foundations of Digital Games, 32:1—32:6.

Kubrick, S. (1968). 2001: A Space Odyssey.

Latitude. (n.d.). Latitude. Retrieved May 6, 2021, from https://latitude.io/

Latitude. (2021, April 28). Update to Our Community. Latitude. Retrieved December 10, 2021 from https://latitude.io/blog/update-to-our-community-ai-test-april-2021/

Marshall, C. (2021, April 28). AI Dungeon’s new filter for stories involving minors incenses fans. Polygon. Retrieved December 10, 2021 from https://www.polygon.com/22408261/ai-dungeon-filter-controversy-minors-sexual-content-censorship-privacy-latitude

Mitchell, A. (2012). Reading Again for the First Time: Rereading for Closure in Interactive Stories.[PhD Thesis]

Mitchell, A. (2013). Rereading as Echo: A Close (Re)reading of Emily Short’s “A Family Supper.” ISSUE: Art Journal, 2, 121–129.

Mitchell, A. (2016). Making the Familiar Unfamiliar: Techniques for Creating Poetic Gameplay. Proceedings of DiGRA/FDG 2016. DiGRA/FDG.

Mitchell, A. (2020). Encouraging and Rewarding Repeat Play of Storygames. In R. Dillon (Ed.), The Digital Gaming Handbook. CRC Press (Taylor and Francis).

Mitchell, A., Kway, L., Neo, T., & Sim, Y. T. (2020). A Preliminary Categorization of Techniques for Creating Poetic Gameplay. Game Studies, 20(2).

Montfort, N. (2003). Twisty Little Passages: An Approach to Interactive Fiction (p. 328). MIT Press.

Neff, G. (2016). Talking to bots: Symbiotic agency and the case of Tay. International Journal of Communication.

-OrionFive-. (2020, September 14). Insert coin? [Reddit Post]. R/ProjectDecember1982. www.reddit.com/r/ProjectDecember1982/comments/isfbx3/insert_coin/

Pötzsch, H. (2017). Playing Games with Shklovsky, Brecht, and Boal: Ostranenie, V-Effect, and Spect-Actors as Analytical Tools for Game Studies. Game Studies, 17(2). Retrieved December 10, 2021 from http://gamestudies.org/1702/articles/potzsch

Pötzsch, H. (2019). From a New Seeing to a New Acting: Viktor Shklovsky’s Ostranenie and Analyses of Games and Play. In Viktor Shklovsky’s Heritage in Literature, Arts, and Philosophy (pp. 235–251). Lexington Books.

Quach, K. (2021, September 8). A developer built an AI chatbot using GPT-3 that helped a man speak again to his late fiancée. OpenAI shut it down. The Register. Retrieved December 10, 2021 from https://www.theregister.com/2021/09/08/project_december_openai_gpt_3/

Rohrer, J. (2020a). Project December [Conversational AI].

Rohrer, J. (2020b, October 1). On the magic potential and bleak future of GPT-3. Medium. Retrieved December 10, 2021 from https://medium.com/@jasonrohrer/on-the-magic-potential-and-bleak-future-of-gpt-3-ff7423ee38d4

Rohrer, J. (2021, September 3). Brand new G4 engine is LIVE [Reddit Post]. R/ProjectDecember1982. Retrieved December 10, 2021 from www.reddit.com/r/ProjectDecember1982/comments/phcsrb/brand_new_g4_engine_is_live/

Schlesinger, A., O’Hara, K. P., & Taylor, A. S. (2018). Let’s talk about race: Identity, chatbots, and AI. Proceedings of the 2018 Chi Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 1–14.

Shklovsky, V. (1965). Art as technique. In Russian formalist criticism: Four essays (pp. 3–24). Lincoln/London: University of Nebraska Press.

Walton, N. (2019). AI Dungeon [Interactive Fiction]. Latitude.

Footnotes

-

In fact, following the publication of an article in the San Francisco Chronicle (Fagone, 2021) about a user who created a matrix based on his late fiancée and the resulting influx of users, OpenAI did indeed “pull the plug for good” (Quach, 2021), and Rohrer moved Project December to the “G4 engine” (Rohrer, 2021). ↩

Cite this article

Mitchell, Alex. "Repetition and Defamiliarization in AI Dungeon and Project December" Electronic Book Review, 9 January 2022, https://doi.org/10.7273/h4xw-ad39