Restoring the 'Lived space of the body': Attunement in Critical Making

In this article, Kelsey Cameron and Jessica FitzPatrick propose attunement, a conceptual intervention that returns lived experience to critical making. They argue for attunement in three areas: disciplinary recognition of making, labs and other university maker spaces, and campus-community engagement. Attunement helps bring equity into critical making, highlighting how larger systems shape individual acts of making.

When we introduce critical making projects to our students, they are excited to think about themselves as designers and about the materials they will work with. However, they do not consider how their making process fits into larger systems. For example, when prototyping augmented reality experiences, students focus on what they can get players to do: how they can anchor stories to spaces on and off campus and create interactions around them. They are less attentive to the fact that their players are people and that their AR stories are anchored in community spaces. For this reason, students need help thinking through the ways lived experiences intersect with what they build. We have designed assignment sequences that try to guide students through this connection (Cameron and FitzPatrick 2021) but inattentiveness to lived experience is not only a problem in AR design; it is a structural problem in the field of critical making more broadly.

As a practice, critical making unites theory with materiality, crediting made artifacts as more than objects of scholarly analysis. Making becomes a mode of conducting scholarship in itself, for the process of hands-on creation generates its own theoretical insights. Over the past decade, higher education institutions have invested in critical making. Its rise is related to a number ofcampus developments: the shift towards STE(A)M, the turn to cultivating campus-industry relationships, and the growth of project-based learning (Krajcik and Blumenfeld), flipped classrooms (Akçayır and fitzAkçayır), and other pedagogies that emphasize active student engagement. The investment in critical making manifests in campus spaces: “Media labs, hacker zones, makerspaces, humanities labs, fab labs, tech incubators, innovation centers, hacklabs, and media archaeology labs” (Wershler, Emerson, and Parikka). Such physical structures coordinate with hiring priorities and curricular offerings (for example, the University of Pittsburgh’s BA / BS in Digital Narrative and Interactive Design has a Critical Making track). As seen in these developments, critical making is at a point of institutionalization which is the exigence for our project here. We propose that now is the time to reconceptualize the values of critical making in order to promote equity and access. This is a particularly urgent problem as academia faces a moment of reckoning with its systemic erasure of marginalized experience.

In this article, we propose attunement as a way of recentering critical making in lived experience. Critical making often reduces makers to disembodied hands and brains: entities that do material work but are not shaped by lived experience or affiliation with particular forms of identity. To address this reduction, we turn to Matt Ratto’s foundational theorization of critical making. By unpacking the relationship between bodies and making, we extend Ratto and propose our own framework, attunement, that emphasizes the structural in making. We illustrate the value of attunement in three arenas: disciplinary recognition of making, labs and other university maker spaces, and campus-community engagement. First, we explore how identity categories like gender mediate the value ascribed to individual makers and their projects through video-based critical making work. Then we move beyond individual makers into the communal space of the lab. As places of trial, failure, and iteration, labs supposedly welcome anyone, but their design can exclude potential makers. Finally, we show how, in the context of community engagement, critical making needs to prioritize community agency over university desires.

Pitching Attunement

In building our framework of attunement, we turn to the work of Matt Ratto. In an influential 2011 article, Ratto positions critical making as a way to “reconnect our lived experiences with technologies to social and conceptual critique” (253). This move is necessary, he argues, because conceptual accounts of technology are often totalizing and deterministic, at odds with messy material realities. For example, theorizations of the liberatory potential of Web 2.0 feel very detached from the experience of setting up a WordPress blog. Purely conceptual accounts are thus prone to “overly optimistic or pessimistic descriptions of [technology’s] effects” (Ratto 253). To avoid this pitfall, critical making aspires to theorize from how humans and technological objects exist together in the world.

There are benefits and limitations to this initial formulation. One aspect of it particularly useful for our project is Ratto’s emphasis on sociality. He writes that, in distinction with product-focused design fields, prototypes in critical making:

are considered a means to an end, and achieve value though the act of shared construction, joint conversation, and reflection. Therefore, while critical making organizes its efforts around the making of material objects, devices themselves are not the ultimate goal. Instead, through the sharing of results and an ongoing critical analysis of materials, designs, constraints, and outcomes, participants in critical making exercises together perform a practice-based engagement with pragmatic and theoretical issues. (Ratto 253)

The value of critical making comes from the movement of materials and ideas through circuits of people. Significantly, Ratto’s critical making examples all happen in public: at conferences and workshops that bring people together. As these venues make clear, critical making is not about a single maker encountering their individual set of materials, but rather the way that shared experiences of making can shape collective conversation.

The second piece of Ratto’s theory we want to develop is the emphasis on lived experience. For Ratto, the goal of critical making “is to make concepts more apprehendable, to bring them in ways to the body, not only the brain, and to leverage student and researchers [sic] personal experiences to make new connections between the lived space of the body and the conceptual space of scholarly knowledge” (254). Insisting that bodies, not only brains, are crucial to critical making is significant. However, this articulation universalizes, imagining a standardized body and brain. We need more nuance about how bodies and brains are not separable from identity categories, personal experiences, and structural forms of oppression. This universalizing move is also a limitation of Ratto’s vision of sociality, which accounts for personal experience only through human interactions with technology. As seen through the verb “leverage”, experience is turned into a resource. The priority remains with technology: lived experience matters only so much as it helps produce a better account of technical artifacts and how they work. Any human complexity beyond that frame gets erased, which reveals a problematic hierarchy.

What we pick up and carry forward from Ratto is the value in the “lived space of the body” (254). This phrase is underdeveloped in his initial formulation, but it is a foundational concern we think critical making should return to. Attunement is the method we propose for attending to the richness of embodiment and lived space. As Sara Ahmed writes, many appeals to embodiment fail to offer “substantive analysis of how ‘bodies’ come to be lived through being differentiated from other bodies” (41). Attunement means considering the histories, systems, and physical environments that shape the lives of bodies in the world. And it is not only the world that acts upon bodies, but bodies that shape the world. Space is lived: A person’s experiences also influence the structures (physical spaces, institutional processes, historical associations) enfolding them (Soja; Tuan; Massey).

Through attunement we hope to approach the goal of building more equitable university critical making structures. Much as a stringed instrument sounds best only after accounting for its presence in the world (the temperature, the humidity, the time since its last use), we propose that critical making would benefit from a process of attunement. By orienting critical making to bodies and lived spaces, attunement asserts that a maker is immersed and active in the world instead of bubbled in a dedicated making space. Attunement also gestures toward the degree of intervention; we do not need a complete overhaul of critical making, but only to readjust and recenter what is already there. Drawing energy from recent scholarship on the power relations that shape design fields and spaces (Costanza-Chock; Wershler, Emerson, and Parikka), attunement helps us ask questions like: Who gets to make things and what modes of making are valued? How do university making structures prioritize some lived experiences over others?

Fanvids, Gender, and Disciplinary Recognition

In this section, we explore how embodiment and identity categories mediate the value ascribed to making projects. It is tempting to imagine that all potential practitioners have equal access to critical making as a domain: all you have to do is connect a material practice to a theoretical concept and you automatically become a critical maker. Of course it is more complicated than that: as the last section suggests, critical making tends to happen in academic institutions, which restricts its circulation in broader publics. In order to claim the term you have to be aware of it. Thus, critical making excludes a wide range of practices that resonate with the name but do not answer to it (for example, design fields, engineering, and many forms of hobbyist making). The fact of limited applicability is not compelling in itself—it is hard to imagine a sizable public angry about being unable to call what they are doing critical making. However, the dissonance gestures to broader dynamics of inclusion, exclusion, and boundary definition that are significant for the history and future of critical making.

Audiences and institutions determine what counts as critical making. The practice involves individual action but, following Ratto, we emphasize its inherent sociality: it is material experimentation that puts thought in circulation, not just experimentation alone. Attunement encourages us to turn a critical eye on critical making, to look for ruptures in access and recognition and interrogate potential failures in equity. Thus, we should ask: what forms of making are easy to recognize as critical? What requires more justification to earn institutional approval? How can mechanisms of recognition reinforce inequities based in gender, race, class, and other identity categories? Using video as an example, we show that gender mediates the value ascribed to making projects. There is a significant discrepancy in acclaim between video essays analyzing film style (frequently made by men) and fanvids focused on character and relationships (frequently made by women). Even when both sets of creators are academics exercising skills in video editing and composition, their intellectual contributions are judged differently.

To see how this works, we look at Lori Morimoto’s “Hannibal: A Fanvid,” a video project that explicitly engages questions of identity, authority, and boundary making. Published in [in]Transition, “Hannibal: A Fanvid” brings together interpretive practices from academia and fandom to approach the NBC television show Hannibal. Morimoto’s work begins with a contextualizing quote about fan vidding as a practice, detailing how vidders exchange “the pleasures of narrative identification with bodily response” (Burwell). “Hannibal: A Fanvid”then enacts that exchange, constructing a fanvid-style representation of the relationship between the series’ two male leads: FBI profiler Will Graham and Hannibal Lector, characters originating in a series of novels by Thomas Harris and appearing in films like Manhunter and Silence of the Lambs. Morimoto cuts together scenes of the two men in scenarios that emphasize the visceral and the sensuous (eating, breathing heavily, embracing) and sets them to evocative music (“Love Crime” by Siouxsie Sioux and Brian Reitzell). The end result is both a successful fanvid and an argument about the inherent fannishness of the showitself, which creator Bryan Fuller has described as fan fiction (Prudom).

In an accompanying creator statement, Morimoto describes her work as meditating on a number of binaries. It is, she writes:

an exercise in both theory and praxis that attempts to blur the divide separating Quality/melodrama, video essay/fanvid, fan/producer, and academic/fan. Indeed, in claiming authorship of this video as both Lori Morimoto, media and film scholar, and abrae, my Hannibal-loving, vid-producing fandom alter ego, I too enact and inhabit a sometimes-discomfiting liminality that exists somewhere within a muddied gap between academia and fandom. (Morimoto)

Particularly significant for us is the tension Morimoto identifies between fan and academic identities. Implicit in the description of liminality as “sometimes-discomfiting” is the idea that fans and scholars do different things: they approach objects in fundamentally different ways, and so to exist in the “muddied gap” of their intersection is to make a lot of people uncomfortable. This discomfort is as relevant to making as it is to more traditional written scholarship: some genres are presumed to be more rational and more academic—more critical—than others.

In this case, fan traditions of making conflict with many presumptions about what criticality looks like. The fanvid mode of video production—character and relationship focused, presuming familiarity with the source film or show—values embodied reaction and emotional engagement. In academic contexts built around detached contemplation and critique, practices drawn from fandom stick out. We see this disjuncture in one review of Morimoto’s work, where Francesca Coppa writes: “I had a moment where I wondered if Morimoto should try to narrate for the reader some of the choices she made in the video and set out what those choices say about Hannibal both as Fuller has made it and as she is remaking Fuller.” Coppa goes on to decide that this is not a weakness—that Morimoto’s vid is powerful in part because of its refusal to narrate—but her moment of resistance points to the fact that all unions of theory and practice are not equal: audiences trained on scholarly criticism can struggle with fanvidding’s visceral, associative mode of interpretation.

This point is especially clear when comparing fanvid-inspired making projects with video essays. Both fanvids and video essays are vernacular forms of audiovisual criticism that circulate widely on YouTube and in other non-scholarly spaces. They can be made by scholars, but, in the era of widespread nonprofessional access to video editing, the majority of their creators are hobbyists who are neither in academia nor in formal film and media industries. However, video essays earn academic recognition much more easily, for their conventions (a central explanatory voiceover, a focus on aesthetics) mimic the style of scholarly discourse. What matters here is not just critical making itself: it is the genre of making and the kind of body it is associated with. Because of trenchant associations between women and the irrational, work based on female-coded traditions like fandom have to do double duty: insist upon the value of fan intellectual practice and argue for the specific intervention its maker intends.

Attunement teaches us to keep these dynamics in mind as we formalize structures to evaluate critical making projects. [in]Transition is one such structure: the first peer-reviewed academic journal of “videographic film and moving image studies,” it is an attempt to codify norms and evaluative criteria for video scholarship. By publishing each video alongside a creator statement and peer reviews, [in]Transition assimilates video-based critical making into a form the academy can recognize and credit (for example, in the process of tenure review). This goal is explicit in [in]Transition’s about page, which explains that publishing peer reviews helps to “set the terms of evaluation for videographic work, and contextualize it for acceptance and validation by our discipline.” Attunement reminds us that our evaluative terms matter. Writing on fan creative production, Suzanne Scott documents the difference in the media industry’s positioning of fanboys and fangirls: the former earn validation and the latter dismissal. Clearly, we need to grapple with how to credit making-based scholarship. But we need to avoid importing existing gendered hierarchies while we do so. The fact that a venue like [in]Transition published a fanvid-style project is a positive sign, but the process of unlearning gendered bias is ongoing and important. If we fail in this work, we reinforce inequalities already rampant in higher education and dissuade those in precarious positions from engaging in critical making at all.

Crossing the Threshold: Labs as Lived Space

When considering access and inclusion in critical making, attunement draws our attention to how humans interact with spaces. On a campus, labs and makerspaces host makers individually or as part of a class as they work through design processes. Labs encompass physical elements (equipment, tables, room dimensions, lighting, etc.), social practices, and procedures that guide what happens within them. Tuning to these elements of the lab is important because they establish norms for campus making: labs train makers in what and who critical making includes. Those assumptions outlast a maker’s time in a lab. As students move out into the world, they carry and replicate what they learned on campus. While tech fields often frame diversity as a pipeline problem, scholars and industry practitioners have revealed the exclusionary structures which make them actively hostile environments (Cheung; Gray and Suri; Jeong and Becker; Roberts; Toh).1 Campus making labs offer a needed opportunity for intervention in establishing more welcoming norms (Livio and Emerson 288). Through attunement, we can reconsider what has become rote, shifting from a focus on providing equipment to a richer conception of access. Attunement first draws our attention to how makers enter labs.

The way to welcome someone into a lab space—indeed any space—is through the threshold. In stories, doorways and portals have power: vampires cannot cross without permission, secret entrances indicate privileged knowledge, and choosing door number one can secure fabulous riches or doom you to a perilous end. Just as in fiction, lab thresholds have power. They are emblematic of the lab experience, shaping your future making encounter or turning you away.

Consider these makerspace thresholds from different institutions. Each one serves as an entry point for makers and communicates lab priorities.

[ngg src=“galleries” display=“basic_imagebrowser”]

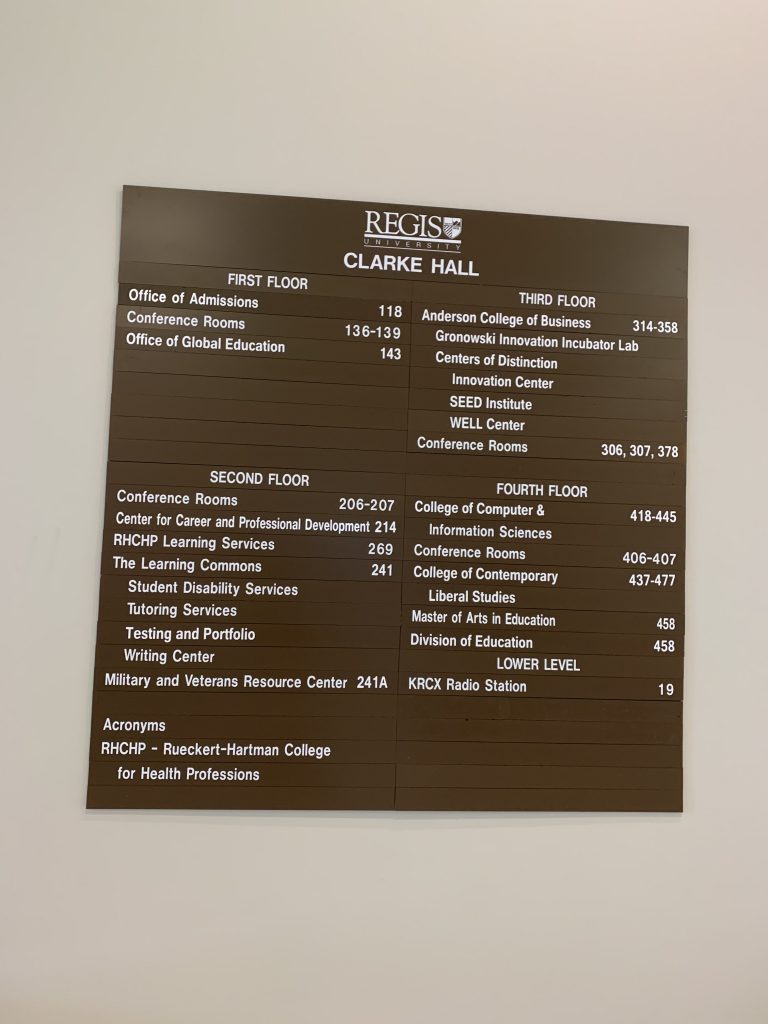

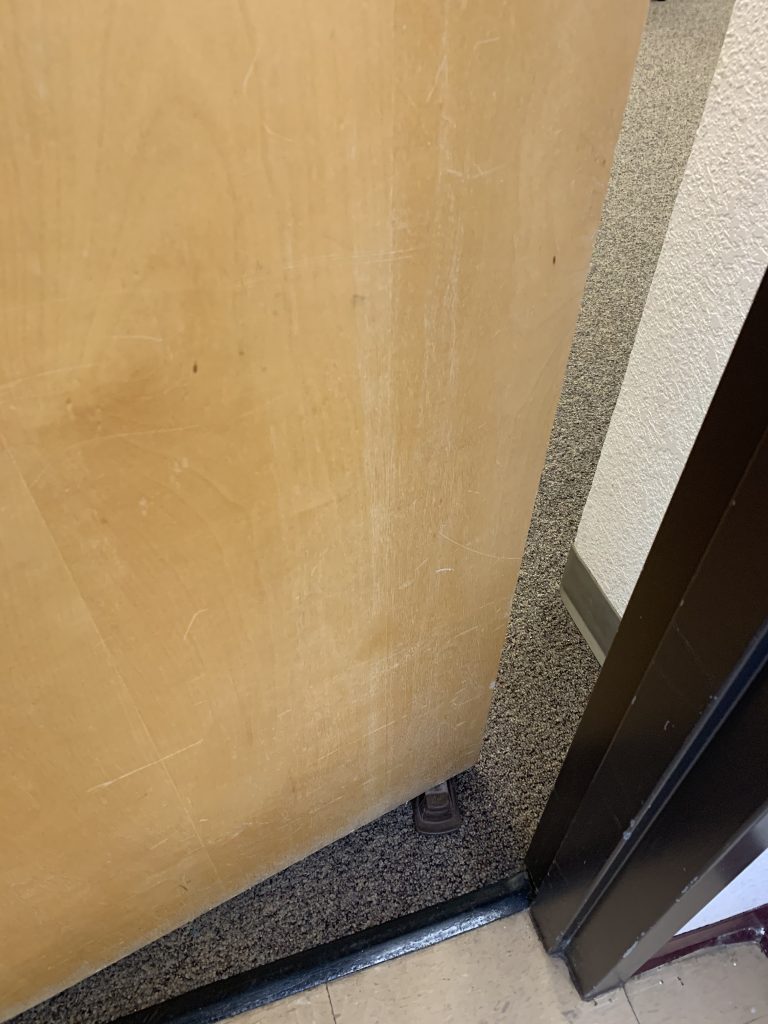

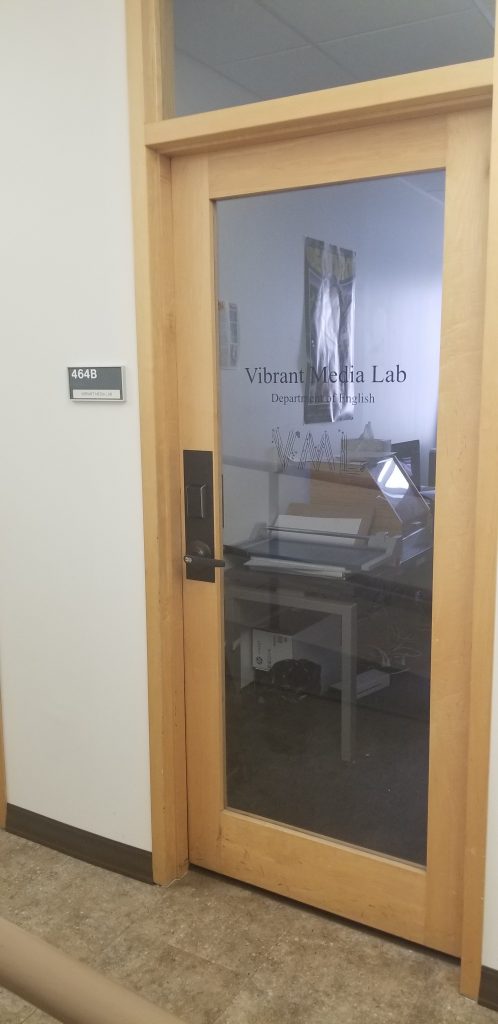

To understand the power of portals, we look at lab thresholds on our own campuses. One of us works at Regis University, a small, regional institution in Denver, Colorado. Like many institutions of this kind in the era of COVID, Regis has limited technology resources that are subject to intensifying budgetary restrictions. While there are plans for a dedicated maker lab, right now the campus only has scattered spaces for making, including a computer classroom and an audiovisual (AV) editing lab. These are out of the way and hard to find: they are both in the basement of their respective buildings and the AV lab does not appear in the lobby’s directory (Figure 1). Finding your way to these spaces thus presumes prior knowledge of what they are and how they might be used (Figure 2). Once there, further barriers to access come into play. Consider the threshold of the AV lab: the door is made of solid wood and closed and locked at all times (Figure 3). Thus, it provides no sense of what happens on the other side. To open the door, users must have keycard access programmed into their university ID.

In this threshold, physical barriers dovetail with institutional ones. Often, labs are open only to students in specified classes and are affiliated with one faculty figurehead who controls access. This is, in part, a move to protect expensive equipment. Unfortunately, the impulse to protect sequesters making spaces away from students and other faculty, and can create access procedures that are slow and strewn with red tape (Figures 4 and 5). We see the downside of this move at Regis, where the AV lab was under the direction of one faculty member. When that person left - taking the only faculty keycard access with them - the department the AV lab belongs to could not access their lab space for the rest of the year. Even when lab doorways are passable, staffing is important - there are often too few people controlling and maintaining lab domains. Regis reminds us that lab access is a function of both physical and human infrastructure.

The other of us works at the University of Pittsburgh (Pitt), a large, research institution in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Pitt has many making spaces on campus, some affiliated with departments and some for general use. The English Department’s Vibrant Media Lab (VML) hosts material and digital making and media archeology. The VML sits between the university’s Gender, Sexuality, and Women’s Studies department and the Center for African American Poetry and Poetics (Figure 6). Unlike at Regis, many students, especially non-technical majors, move past the VML’s threshold. The door has a window, so even when the lab is locked you can peep in and see an arcade cabinet and making projects in progress strewn across the tables (Figure 7). Even at a casual glance, the lab is pretty intriguing: the view from the threshold has the potential to bring in new makers. However, attunement encourages us to consider how that same view could be intimidating. The doorway may be exciting and inspiring if you already know that this is a campus resource which welcomes new makers. Otherwise what you see is a lot of other people’s stuff, and that stuff can feel outside your domain: hard-to-decipher, easy-to-break, expensive-looking, and generally imposing in its chaos (Figure 8).

Labs imagine normative users as being white, male, able-bodied, financially secure, and technically literate. If you do not fit that imagined ideal, making spaces can feel like they are not designed for you. For example, in the VML there are two main rooms for making. Students use both frequently. However, this dual room layout creates limited visibility: Lab users in the backroom have an inadequate eyeline to the lab’s door and the front room. The orientation of the equipment in the back room exacerbates this lack of visibility. To use certain computers and access particular software, the layout forces users to have their back to the door. On the one hand, this is a way to maximize the equipment per square foot in a relatively small space that was retrofitted to be a lab. On the other, equipment-focused layouts may activate trauma from a variety of lived experiences as different as: anxiety, military experience, imposter syndrome, and gendered/sexualized violence.

Clearly, even at more resource rich institutions, labs have limitations. In an ideal world we’d build labs from scratch, with equity as the first priority from the design stage. In the actual world, makerspace directors often have to work with existing spaces and limited staffing. Equity should still be a priority, and attunement helps us work towards that goal from where we are. Through attunement, we can ask the right questions about a space and challenge assumptions about its users.

Neighbors as Makers: Campus-Community Collaboration

We’ve explored how access and equity are imagined within critical making disciplines and physical making structures, but they also matter in the networks of campus-community projects. Much consideration has been given to community engagement and community anchored research, especially through programs of service learning, participatory design, and participatory action (Chak; Delano-Oriaran, Penick-Parks, and Fondrie; Ochocka, Moorlag, and Janzen; Smith, Bossen, and Kanstrup). But often campus-community ventures find it too easy to prioritize university desires over community agency (Baum; Costanza-Chock; Johnston Hurst; Sipos and Wenzelmann). We argue that the rise of critical making exacerbates these tensions: it makes space for hands-on work within academia, but does not always structure that work in ways that are ethical, collaborative, and community centered. By orienting to the specifics of lived space and embodied experience at both the individual and structural levels, attuned campus-community making partnerships can better strive to work in equitable ways.

The emphasis of campus-community partnerships is often about what skills and connections students get out of community engagement. Barbara A. Holland outlines how university project designers only imagine that “the community partner’s role is to provide a laboratory or set of needs to address or explore” (11). This is harmful: in critical making, such a view denies that non-campus community members themself make in various ways and that such making processes have value. Instead, attunement asks: what might be possible in critical making if community members are present as makers, not just consumers of made products? When Rachel Alpha Johnston Hurst organized a digital video making assignment partnering her Women and Gender Studies program with community organizations, she had to work against the connotations of service learning. She had to generate her own framing to position the partnering community organizations as makers dedicating time and expertise to work with students , not as an area for student savior-complex “service” assistance (Johnston Hurst 19). In attuned critical making collaborations, power relationships are explored, not replicated through unthinking assumptions.

One of those unthinking assumptions is that communities even want to work with universities, when in actuality they are often suspicious of campus collaborations. Institutions of higher education are businesses and economic imperatives override ethical community relations. For example, universities in Pittsburgh, the hometown of Fred Rogers, have often acted as ignorant neighbors. This is evident when considering the Hill District, a primarily Black neighborhood which is often targeted for university outreach. But in the past, the city of Pittsburgh and its universities have harmed the Hill District. One vivid example of this harm occurred in 1956, when a city urbanization plan “uprooted” at least 8,000 residents in order to build the Civic Arena, eliminating most of what was known as the Lower Hill and decimating the relationship networks of the neighborhood. The University of Pittsburgh contributed to this community displacement; in order to procure land for a large athletic complex, Pitt forced families on the border of the Hill to relocate in the 1960s. Representational erasures of the Hill have also happened: In 2019 Carnegie Mellon University circulated a “Featured Neighborhoods” map which censored Black communities like the Hill District (Rihl). While the map included all the predominantly white neighborhoods surrounding the Hill, the District itself was noticeably left blank. To rush into a community like the Hill District seeking opportunities for critical making partnerships without accounting for these past tensions would be disastrous.

The Hill District is also a community of makers and cultural producers in its own right. Between the 1920’s and 1950’s, the Hill District was a nationally celebrated cultural center, known by people like poet Claude McKay as “the crossroads of the world”; many others called the neighborhood “little Harlem” for the jazz talent that arose from or traveled there to play. The nationally circulated black newspaper, The Pittsburgh Courier, was based in the Hill, and the neighborhood’s Freedom House Ambulance Service began what is now the national standard for paramedic care. Since 2016 Bekezela Mguni’s work on the Black Unicorn Project has celebrated storytelling as cultural preservation, and the August Wilson House’s development of a community arts center looks to launch in 2021. The Hill District is a resilient and powerful community that has always been involved in vibrant and multifaceted making. Attuned critical making values making processes and spaces that exist outside university domains.

Attunement requires us to remember that space is lived and to engage communities as more than resources. People invested in critical making are starting to think about how to form campus-community partnerships in meaningful ways (Balsamo; Costanza-Chock; Sayers). And universities are too. We see this in how Pitt is attempting to correct its previous mishandling of community relations by establishing two new Community Engagement Centers (CECs), one of which is located in the Hill District. Under Director Kirk Holbrook, the CEC in the Hill District now offers an online training module, “In the Voices of Our Neighbors: Effective and Respectful Engagement in the Hill District” (Pitt CEC). The module instructs potential campus collaborators in best practices co-created with community stakeholders and is required for all faculty and students that wish to engage in collaborative projects. This is one example of how a university is tuning its engagement structures.

You might wonder why we are talking about something so non-specific to critical making. But building structures that acknowledge the value of communities in their own words is important for any critical making project that wants to move beyond the boundaries of campus. These foundations are where campus-community critical making should begin. And at Pitt, project leaders are starting to build towards this ideal, with the CEC collaboration module becoming a standardized part of campus-community making ventures. Thanks to this procedure, projects will start with a concrete sense of community experiences and desires, not only with technologies and learning goals.

The CEC training module also emphasizes the work of self-examination, something else we believe attunement brings to critical making. As we have suggested, campus makers themselves are not homogenous and assuming they are replicates systems of privilege and the overwriting of lived experience. The training module challenges university participants to consider questions like “What do you bring, what are your values, what is your family story?” (Terri Baltimore qtd. in Pitt CEC). This is something we should bring to all critical making partnerships: the position of university maker should be just as examined as community makers.

In Conclusion: Iterating Critical Making

Iteration is a fundamental part of critical making. Annette Vee defines iteration as “working on a problem repetitively, with feedback, to incrementally solve it or improve it.” We find this emphasis on continual, incremental revision useful to apply to critical making itself. Attunement is an iterative model: it revises conceptualizations, structures, and procedures of critical making with lived experience as an orienting value. This work is—and needs to be—an ongoing engagement.

Attunement returns lived experience to critical making, centering that individuals and their acts of making are always placed in larger systems. We have outlined the possibilities of attunement in three arenas: the disciplinary borders of critical making, the spaces used for making, as well as the processes of making. In all three, we highlight that the conceptual side of critical making should not be a reason to universalize minds or bodies. Critical making often imagines a normative body that does not have to deal with questions like: Where will I get childcare coverage? How will I afford a course or equipment fee? How will my assistive devices fit into making spaces? Will my suggestions be heard and valued in collaborative projects? How will I process the difficult emotions (embarrassment, frustration, anxiety) that come with failure and negative feedback? Unattuned critical making can also bracket questions about making’s codified value systems: Why is one form of making valued over others? What effects does this making practice have on other people and communities? How can we equitably enter into making with partners? Do we currently prioritize equipment or people? How is access envisioned in spaces and procedures?

These questions outline the patterns of thought attunement encourages. Attunement helps us imagine a more equitable critical making, a process that is itself ongoing and iterative. Though we include some examples, we have talked about embodiment and lived experience in general terms. Future work could specify and nuance our considerations, drawing on insights from domains like critical race studies, gender and sexuality studies, disability studies, labor and working class studies, and geography and area studies*.* Developing attunement also means being attentive to the specific context of your making project, campus, and makers. We have gestured to our own specifics in the examples above, but asking similar questions about your own contexts may lead you to very different answers or even entirely new questions.

Notes

Tech fields have a long history of these exclusionary practices, especially when it comes to questions of gender and race. For example, Margot Lee Shetterly follows the story of black women computers, early programmers, and engineers working for—and being held back in—NASA during the space race. Similarly, Mar Hicks portrays how the United Kingdom systematically weeded women out of the computing work force as it became professionalized.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to the makerspace at Temple University, the Science Library Makerspace at the University of Georgia, the Open Lab at the University of Pittsburgh, and the Wakerspace at Wake Forest University for sharing photographs of their thresholds.

Works Cited

Ahmed, Sara. Strange Encounters: Embodied Others in Post-Coloniality. Routledge, 2000.

Balsamo, Anne. Designing Culture: The Technological Imagination at Work. Duke UP, 2011.

Baum, Howell S. “Fantasies and Realities in University-Community Partnerships.” Journal of Planning Education and Research, vol. 20, Association of Collegiate Schools of Planning, 2000, pp. 234-246.

Burwell, Catherine. “You Know You Love Me: Gossip Girl Fanvids and the Amplification of Emotion.” Feminist Media Studies, vol. 15, no. 2, 2015, pp. 306-323.

Cameron, Kelsey and Jessica FitzPatrick. “Designing Lived Space: Community Engagement Practices in Rooted AR.” Augmented and Mixed Reality for Communities, edited by Joshua A. Fisher, Taylor & Francis, 2021, pp. 83-102.

Chak, Choiwai Maggie. “Literature Review on Relationship Building for Community-Academic Collaboration in Health Research and Innovation.” MATEC Web of Conferences, vol. 215, EDP Sciences, 2018, pp. 1-9, doi:10.1051/matecconf/201821502002.

Cheung, Philip. “A Recruiter Joined Facebook to Help Improve Diversity. He Says its Hiring Practices Hurt a Lot of People.” 3 May 2021, The Philadelphia Tribune, https://www.phillytrib.com/news/business/a-recruiter-joined-facebook-to-help-improve-diversity-he-says-its-hiring-practices-hurt-people/article_c23e44fe-cbb6-5bb1-bf0f-5e43db3d283d.html. Accessed 3 May 2021.

Coppa, Francesca. Review of “Hannibal: A Fanvid.” [in]Transition, 2016, mediacommons.org/intransition/2016/10/06/hannibal-fanvid.

Costanza-Chock, Sasha. Design justice: Community-led practices to build the worlds we need. MIT Press, 2020.

Delano-Oriaran, Bola, Marguerite W. Penick-Parks, and Suzanne Fondrie. The SAGE Sourcebook of Service-Learning and Civic Engagement. SAGE Publications, 2015.

Fuller, Bryan, creator. Hannibal. NBC, 2013-15.

Gray, Mary and Siddharth Suri. Ghost Work: How to Stop Silicon Valley from Building a New Global Underclass. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2019.

Hicks, Mar. Programmed Inequality: How Britain Discarded Women Technologists and Lost Its Edge in Computing. MIT UP, 2017.

Holland, Barbara A. “Reflections on Community-Campus Partnerships: What Has Been Learned? What are the Next Challenges?” Higher Education Collaboratives for Community Engagement and Improvement, edited by Penny A. Pasque, et al., National Forum on Higher Education for the Public Good, 2005, p. 10-17.

Jeong, Sarah and Rachel Becker. “Science Doesn’t Explain Tech’s Diversity Problem - History Does.” The Verge, 19 Apr. 2019, www.theverge.com/2017/8/16/16153740/tech-diversity-problem-science-history-explainer-inequality. Accessed 1 May 2021.

Johnston Hurst, Rachel Alpha. “Evaluating the Effects of Community-Based Praxis Learning Placements on Campus and Community Organizations in the ‘Doing Feminist Theory Through Digital Video’ Project.” Feminist Praxis Revisited : Critical Reflections on University-Community Engagement, edited by Amber Dean, et al., Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 2019. ProQuest Ebook Central, ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/pitt-ebooks/detail.action?docID=5628114.

Livio, Maya and Lori Emerson. “Towards Feminist Labs: Provocations for Collective Knowledge-Making.” The Critical Makers Reader: (Un)learning Technology, edited by Loes Bogers and Letizia Chiappini, INC Reader #12, Institute of Network Cultures, 2019, pp. 286-298.

Manhunter. Directed by Michael Mann, 1986.

Massey, Doreen. “A Global Sense of Place.” Space, Place, and Gender, University of Minnesota Press, 1994, pp. 146-157.

Morimoto, Lori. “Hannibal: A Fanvid.” [in]Transition: Journal of Videographic Film and Moving Image Studies, vol. 3, no. 4, 2016, mediacommons.org/intransition/2016/10/06/hannibal-fanvid.

Ochocka, Joanna, Elin Moorlag, and Rich Janzen. “A Framework for Entry: PAR values and engagement strategies inc community research.” Gateways: International Journal of Community Research and Engagement, vol. 3, 2010, pp. 1-19.

Prudom, Laura. “‘Hannibal’ Finale Postmortem: Bryan Fuller Breaks Down That Bloody Ending and Talks Revival Chances.” Variety, 29 Aug. 2015, variety.com/2015/tv/news/hannibal-finale-season-4-movie-revival-ending-spoilers-1201581424/. Accessed 1 Apr. 2021.

Pitt Community Engagement Centers. Toolkit Area: In The Voices of Our Neighbors: Effective and Respectful Engagement in the Hill District. 2020, pitt.co1.qualtrics.com/jfe/form/SV_0voTgfd9aKIgzJ3.

Ratto, Matt. “Critical Making: Conceptual and Material Studies in Technology and Social Life.” The Information Society, vol. 27, 2011, pp. 252-260.

Rihl, Juliette. “CMU created a map excluding Pittsburgh’s Black neighborhoods. It’s not the only one.” Public Source, 6 Feb. 2020, www.publicsource.org/cmu-created-a-map-excluding-pittsburghs-black-neighborhoods-its-not-the-only-one/.

Roberts, Sarah. Behind the Screen: Content Moderation in the Shadows of Social Media. Yale UP, 2019.

Sayers, Jentery. “Tinker-Centric Pedagogy in Literature and Language Classrooms.” Collaborative Approaches to the Digital in English Studies, edited by Laura McGrath, Computers & Composition Digital Press/Utah State UP, 2011, pp. 279-298.

Scott, Suzanne. “The Trouble with Transmediation: Fandom’s Negotiation of Transmedia Storytelling Systems.” Translating Media, vol. 30, no. 1, 2014, 30–34.

Shetterly, Margot Lee. Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space Race, Harper Collins, 2016.

Sipos, Regina, and Victoria Wenzelmann. “Critical Making With and For Communities.” Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Communities & Technologies - Transforming Communities, ACM, 2019, pp. 323–30, doi:10.1145/3328320.3328410.

Smith, Rachel Charlotte, Claus Bossen, Anne Marie Kanstrup. “Participatory Design in an Era of Participation.” CoDesign, vol. 13, no. 2, Taylor & Francis, 2017, pp. 65–69, doi:10.1080/15710882.2017.1310466.

Soja, Edward. Thirdspace: Journeys to Los Angeles and Other Real-and-Imagined Places. Blackwell Publishing Inc., 1996.

The Silence of the Lambs. Directed by Jonathan Demme, 1991.

Tuan, Yi-Fu. Space and place: The perspective of experience.University of Minnesota Press, 1977.

Toh, Michelle. “Ellen Pao: Meritocracy in the Tech Industry is a Myth.” Los Angeles Daily News, 21 Apr. 2021, www.dailynews.com/2021/04/21/ellen-pao-meritocracy-in-the-tech-industry-is-a-myth-2/. Accessed 1 May 2021.

Vee, Annette. “Iteration.” Digital Pedagogy in the Humanities: Concepts, Models, and Experiments, edited by Rebecca Frost Davis, Matthew K. Gold, Katherine D. Harris, and Jentery Sayers, Modern Language Association, 2020.

Wershler, Darren, Lori Emerson, Jussi Parikka. The Lab Book: Situated Practices in Media Studies. Minnesota Press, manifold.umn.edu/projects/the-lab-book.

Footnotes

-

Tech fields have a long history of these exclusionary practices, especially when it comes to questions of gender and race. For example, Margot Lee Shetterly follows the story of black women computers, early programmers, and engineers working for—and being held back in—NASA during the space race. Similarly, Mar Hicks portrays how the United Kingdom systematically weeded women out of the computing work force as it became professionalized. ↩

Cite this article

FitzPatrick, Jessica and Kelsey Cameron. "Restoring the 'Lived space of the body': Attunement in Critical Making" Electronic Book Review, 12 September 2021, https://doi.org/10.7273/j480-c578