Revealing Noise: The Conspiracy of Presence in Alternate Reality Aesthetics

Adam Pilkey argues that the ARG Year Zero's use of "revealing noise" allows and encourages the audience to help in the building of the narrative by becoming participants in a conspiracy theory within the ARG. Pilkey argues that "The Presence" found in the Nine Inch Nails album and corresponding ARG, Year Zero, symbolizes and denies a truth, which in turn provides a means that furthers the resources that constructs conspiracy theories in this alternate reality.

Introduction

As digital games become an increasingly popular form of entertainment, social anxieties and curiosities around them have increased in proportion. Like the emergence of previous media, those who are ill informed about the particulars of modern games use them as scapegoats for a number of social problems. These criticisms are made explicit in a variety of ways, including studies linking violent tendencies to game play and increasing levels of other anti-social behavior (Nielsen et al. 229); accusations that heavy exposure to games distorts players perception of reality (McGonigal “Real Little Game”); and more general concerns regarding games and their apparent correlation with the breakdown of established social order (Nielsen et al. 138). Criticisms have been inferred by notable public figures such as President Obama, who recently used “gaming the system” as a metaphor for engaging in illicit trade practices (The Guardian, November 14 2011), thereby demonstrating the political potential in capitalizing on what essentially amounts to a discourse of “anti-gaming hysteria.” This discourse diminishes the creative and cultural importance of these games, and researchers, developers, and game enthusiasts are constantly developing new games and genres in an attempt to flush out the value of this increasingly popular mode of entertainment.

Alternate Reality Games (ARGs) emerged in 2001 after the design for a sophisticated viral marketing campaign for a film evolved into an immersive, entertaining game experience. It attracted a dedicated player community numbering in the thousands (McGonigal “This is Not a Game” 110), and a wider audience numbering in the millions (Dombrowski et al). ARGs can be roughly thought of as fragmented narratives hidden within elaborate puzzles, which players then work to piece together. In presenting audiences with such a challenge, it disrupts the more traditional producer-consumer relationship of cultural production by giving audiences the freedom to challenge (and even subvert) the creative control of a particular work. To put it another way, ARGs give audiences both the opportunity and the tools to help create a work. Such democratization of the production process naturally gives oppositional/negotiated readings a more prominent voice, and this discussion concerns itself with how giving these voices the opportunity to be heard is a unique (and some might even say vital) component of digital aesthetics.

42 Entertainment’s Year Zero is a well-known ARG designed to promote an album of the same name by the popular American rock group, Nine Inch Nails (NIN). The game has been the subject of past academic discussions (Dombrowski et al.; Hall) and widely praised within the entertainment industry. In addition to winning two “Webby” awards from the International Academy of Digital Arts and Sciences (Webby Awards), the game was described by Ann Powers from the LA Times as “a total marriage of pop and gamer aesthetics”, and is the topic of a feature on 42 Entertainment’s website (42 Entertainment). Many of these sources praised the way the thematic and narrative content of the game resonates with the aesthetic possibilities afforded by ARGing. Year Zero’s accomplishments in this respect encapsulates the impact of technology and economics on the development of digital aesthetics, a relationship Roberto Simonowski identifies as integral to the logic of new media (73). For these reasons, Year Zero provides an excellent object to explore the aesthetic dimensions of ARGs. The remainder of this discussion will examine how Year Zero invokes conspiracy theory like aesthetics, mainly through its use of “revealing noise.”

How Noise Obscures and Reveals Meaning

“Revealing noise” is a theoretical concept designed to highlight recent innovations in Shannon’s seminal theoretical conception of communication. As Krapp outlines in the introduction of his book, Noise Channels: Glitch and Error in Digital Culture, Shannon’s understanding of noise as a strictly “parasitic” or degrading element to the communication process is somewhat antiquated, as digital technologies can now utilize noise as a tool to enrich the communication process (xv-xvi). Krapp does not suggest abandoning Shannon’s infamous model, but it seems clear that digital technologies are beginning to encode distortion or “noise” with real information, thereby using it as a way of revealing rather than hiding. In understanding how affordances of digital technologies can enhance the aesthetic experience of a particular work, it is important to consider the design of these technologies and how these both constrain and enable artistic expression.

As ARGs intentionally co-opt social communication technologies as storytelling devices, they depend on the ability of audiences to simultaneously interpret information in both the presence and omission of signals. These social communication technologies are not optimal for mass media endeavors. This, however, does not negate the potential of developers to use them, and ARGs realization of this is one of the unique properties of the genre. It plays with the practice of using technologies within a specific set of social relations. In doing so, it facilitates creativity in both the encoding and decoding stages of communication. 1 Krapp asserts that “expressions of cultural creativity operate in embracing rather than overcoming or ignoring limitations” (xiii), thereby suggesting they play with these limitations and use them as literary devices in their narratives. Much of the aesthetic appeal in Year Zero stems from its ability to co-opt the limitations and restrictions of particular media into its diegesis.

Games in general have put themselves at the forefront of information media by encouraging players to engage with technologies as interactive communication systems. Games are an information medium that explicitly relies on players to “play” with the objects as meaning-making systems. While poststructuralists such as Barthes and Derrida maintain that all works are objects that encourage play, this is not a perspective shared by the general populace. Children are not taught how to play books (or with books) or play television (or with television). In general, “old media” are technologies that appear to facilitate passive reception practices. Barthes in particular suggests that enacting his poststructuralist conception of play liberates text from the entrapment of a work (“From Work to Text” 1474), and Pacey points out that the conventions governing the use of technologies generally displace socio-political anxieties onto minor technical details (74). Krapp seems to accept these assertions, but is critical of them and points out that passive consumption praxis may be a myth, one forgotten by hegemonizing the deficiencies of the old media institutions via socialization (41). New media challenges this myth by using interactive technologies as a tool that enables (and often requires) audiences to produce their own messages, thereby disrupting the role of audiences as active producers of meaning that are gagged by a lack of access to media technologies. The proliferation of electronic games (and game genres) is a reaction to the growing omniscience of computing technologies, thereby giving these games an increased level of affordance in playing with the errors and glitches in meaning making systems (Krapp 76). Year Zero demands that players play with various types of digital media by creating a narrative questioning not only its own diegesis, but also the player’s relationship to hegemonic social structures.

The concept of play utilized by ARGs depends on this reflexive and critical mode of play, and therefore this study will examine how ARGs produce conspiracy theories. As discussed above, ARGs encourage players to play with the various modes of interaction available to them, play with the semiotic constitution of the media, and play with the one another. Playing with the in-game works facilitates “critical and self-aware exploration” (Krapp 77) via mediated textual production. Or more specifically, the theorization of conspiracies through the formulation of “alternative narratives that tend to virtualize history and politics whenever official accounts appear too selective and tendentious…conspiracy theory has to be recognized as an insistence, however degraded, on the readability of our world with new technologies” (Krapp 34). Conspiracies appear when information is somehow incomplete or lacking in consistency and clarity, when it is ambiguous. The importance of the conspiracy theory to the ARGs diegesis is the formulation of an objective interpretation of the overwhelming degree of “revealing noise” in ARG communication, and as such, the process of playing the ARG is akin to the process of theorizing. Year Zero’s diegesis depicts a future where the United States government is at the center of an elaborate conspiracy against its people, and the game explores this by giving the players the means to explore and possibly subvert this conspiracy and its apocalyptic outcome.

Analysis of ”The Presence”

Figure 1.1: “The Presence” as depicted on Nine Inch Nails’ 2007 album Year Zero.

An analysis of the depiction of “The Presence” in Year Zero facilitates the exploration of the use of digital technologies on the aesthetics of ambiguity. “The Presence” is a fictitious concept that is never fully explained in Year Zero, and instead encourages players to explore on their own. The most succinct explanation is that it “is represented as a ghostly arm reaching down from the sky,” (“The Presence”). 2 This analysis follows the representation and development of “The Presence” through the various in-game media used to construct the work Year Zero. The specific examples discussed provide a cross-section of the types of media used to construct the game’s fiction, thereby highlighting the particular affordances given by the different types of media it utilizes to form its narrative. Thus, the media discussed includes songs from the album, websites, and videos posted to file sharing services. By doing so, this analysis aims to illustrate that ARGs and their unique mode of play capitalizes on perceived ambiguities, thereby generating conspiracy theories as a part of ARG narratives.

“The Presence” in The Warning

“The Warning” is a song from the Year Zero album. Just as in all other songs in the album, it ties into the larger diegesis of the Year Zero story, and it draws upon a variety of tools do so. Conventionally, one can hear traces of the narrative, the themes, and the style in the prose of the lyrics, as well as the composition of the music. However, digital technologies can unpack different meanings and details encoded within the song.

Inconsistencies in the fidelity of the song as a signal introduce meaningful ambiguity, thereby issuing a challenge to conventional interpretive practices. These inconsistencies can take on a variety of forms and embodied in a variety of textual details, and dictated largely by genre conventions of popular music and their associated consumption practices. The song follows a largely conventional format, alternating between verse and chorus components with poetry and rock music overlain. Songs, just like many other art forms, are not necessarily designed to optimize clarity or simplicity. Ambiguity is an effective tool to distort meanings, or open up works to negotiated interpretations or symbolic participation by audiences. “The Warning” is able to offer this ambiguity in several ways. For example, the use of objective pronouns as opposed to nouns or other explicit identification symbols clouds the lyrical content of the song:

Some say it was a warning

Some say it was a sign

I was standing right there

When it came down from the sky

The way it spoke to us

You felt it from inside

Said it was up to us

Up to us to decide (Reznor)

The excessive use of pronouns intentionally fails to identify the actors in this passage. It clearly describes actions, settings, and other narrative elements, but nothing interpretable as an active agent. By clearly communicating the presence of an agent without providing identification information, the actor becomes an object defined by ambiguity. This lack of clarity about the message of the song provides an appeal to the audience for further interpretive work.

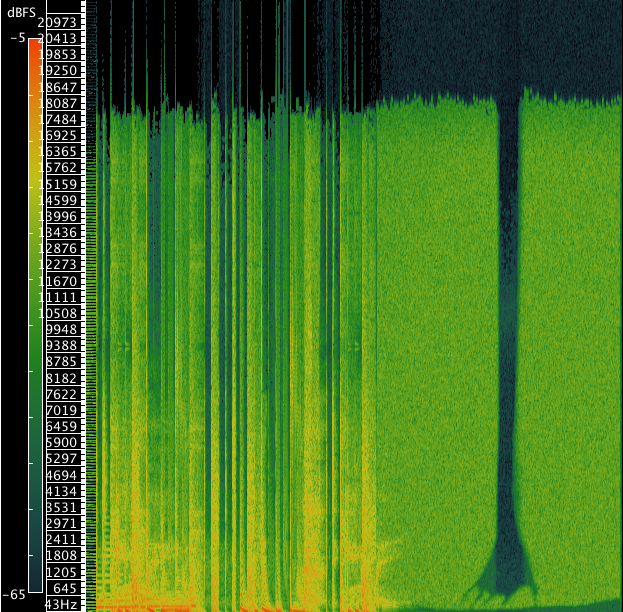

Ambiguity provides audience members with an interpretive resource in this scenario. While there is no way to guarantee an audience will respond to ambiguity in a specific way, creators can now provide content to facilitate varying degrees of interaction without facing crippling production expenses. McGonigal describes this phenomenon as based upon “critical and constructive” relationships with digital technologies (“Why I Love Bees” 214). Those members of the audience who possess a heightened awareness of the affordances of digital technologies can use that knowledge to engage with the work at a deeper level. “The Warning” exemplified this by using digital technologies to encode additional information into the song. The last 5 seconds, which sounds like static, contains digital information that is not audible by an audio signal processor. However, once the signal is processed visually via the use of a spectrograph, the additional information adds to the fidelity of the signal. As demonstrated by Figure 1.2, the low fidelity at the end of the song contains visual information. The image, which sounds like the static fading in and out, has many similarities with the image from the album cover (Figure 1.1). The game community refers to this image as “The Presence” and describes it as a hand descending “from above.” The symbol of a hand coming down from something above refers back to the stanza discussed earlier, inferring the possibility that “The Presence” is one of the agents addressed in the lyrics.

Figure 1.2: A Spectrogram of the last five seconds of “The Warning.”

Ambiguities in “The Warning” invited the development and inclusion of this digitally savvy interpretive strategy to the meaning making process, thereby highlighting the multidimensional concept of “play” offered by Year Zero. In this example, “The Warning” clearly employs a variety of communication techniques, and relies on both clarity and ambiguity to challenge players/listeners interpretations of the song. Combining its use of digital technologies with traditional linguistic and aesthetic techniques encouraged Year Zero’s audience to play with the text on a variety of levels. The potential to use digital tools to augment and enhance the more conventional meaning making techniques used by audiences encouraged them to engage in a “play” process to explore and resolve these “meaningful ambiguities”. Year Zero helped audiences realize this potential by at once obscuring and revealing pieces of information, which according to McGonigal invites audiences to take a more active role in the meaning making process:

There were no limits on plausible actions to take. At the same time, there was enough structure and specificity of data to make the application of data processes a challenging, time-consuming affair. So there was never a shortage of supporting work to be done…ambiguous situations require people to participate in meaning making” (Why I Love Bees 214).

McGonigal’s statements are applicable to the situation described above. The data provided by the digital, lyrical, and musical content of “The Warning” simultaneously provided and obscured information to the audience, thereby giving them the opportunity to interact with the text without offering them a comprehensive blueprint to do so. Audiences are therefore encouraged/required to experiment, innovate, and otherwise open themselves up to new experiences of the text. Thus, using digital technologies to facilitate new forms of play/textual experience adds another dimension to the song, the album, and the entire diegesis of Year Zero by exposing information that would otherwise remain invisible.

“The Presence” in YouTube

The Year Zero game engaged players in multiple digital (and non-digital) environments. Due to the high degree of participation expected from ARG players, social networking sites, blogs, and other web sites hosting user-generated content are extremely popular platforms for storytellers to engage audiences. YouTube, which is perhaps the most popular video sharing resource on the Internet, provided an excellent forum for the game creators to distribute content, and for the player community to circulate ideas. Additionally, the degree of anonymity enjoyed by YouTube users allows everyone to capitalize on the immersive capabilities of the site by hiding the identity of posters. Thus, the community is unable to determine which contributions are “authentic” (posted by game developers), and which contributions are from other players attempting to engage and develop the story.

Communal access to YouTube allowed players to develop the concept of “The Presence.” YouTube lets users to create profiles and upload content, thereby providing a certain degree of anonymization in the creative process. ARGs like Year Zero are therefore able to appropriate content into its diegesis without a single source able to claim authorial intent (with exceptions), thereby democratizing the writing process. Given the ambiguous nature of “The Presence” this affordance of YouTube enabled a variety of contributors to develop the concept in different ways, thereby contributing to its ambiguity while simultaneously developing the game’s diegesis. For example, what is perhaps the most prominent video featuring “The Presence” comes from what was originally used as a trailer for the album, but was eventually revealed as an in-game artifact (“USBM Leak”). The video adopts its style from the found footage genre, essentially asserting the idea that the video is something made by a non-professional cinematographer. It was posted to YouTube by someone (or something) with the user name USBureauofMorality, which was later revealed as the branch of the US government responsible for domestic security within the Year Zero narrative universe. YouTube describes the footage as taken by a couple driving on an American highway, and depicts a passing landscape that is briefly interrupted by an illegible road sign. Eventually, a large hand appears to come down from the sky and hit the ground. The image begins to distort, and it eventually cuts out. The sound throughout the video contains inaudible static; quiet at first and then suddenly extremely loud once “The Presence” appears in the video. The sudden shift from the serenity of the passing landscape to the chaotic appearance of “The Presence” seems intentional; as the caption at the beginning of the video states that “the arm has been known to cause electronic devices to malfunction.” This portrayal of the “The Presence” capitalizes on the questionable nature of content posted on YouTube. The identity and reliability of the footage are directly questioned, as audiences are unable to consider the meaning of the video without considering the underlying concerns of the source and meaning of the message. The fact that the video was originally posted as a trailer for the Year Zero album (“Nine Inch Nails–Year Zero”) indicates that professionals working for the artist produced the video, but its inclusion in the game narrative may or may not be part of the design. The identity of the user, USBureauofMorality, is a lingering mystery upon which audiences are left to speculate. The quotation at the beginning, the veiled identity of the poster, the distorted sound and imagery, are all reinforced by both the YouTube medium and the diegesis of Year Zero.

Figure 2.1: Contact sheet of images taken from the “USBM Leak: The Presence” YouTube video.

These questions provide a pretext for players to engage with and develop “The Presence” by using the affordances of YouTube. YouTube contains several more videos containing explicit references to “The Presence.” As with all YouTube videos, the identity of the poster is often unclear, and the content of the videos explore “The Presence” in different ways. Sometimes the portrayal of “The Presence” is different or contextualized differently through the use of descriptive elements such as comments, titles, etc. The freedom to explore and discuss these representations in a symbolic environment speaks to the strength of the new media to democratize the storytelling process. One such video that makes use of this feature is the “Parepin: What I Saw” video (“What I Saw”). This video contains considerably less visual information, and features what appears to be the distorted image of a giant hand hovering above a flat surface.The audio track has a digitally distorted, reverberating voice and an additional static track overlain, making the words themselves difficult to decode. Certain words and phrases are highlighted in between the echoes and static, andallusions to “knowing,” “having two eyes”, and “he’s coming again” are clear. The image is clearly not identical to previous depictions of “The Presence,” all of which maintain a certain pattern and are attributable (albeit debatably) to the actual producers of the game. It is a sort of echo, and goes to great lengths to represent itself as a piece of “fan fiction.” 3 Besides exploiting the obvious affordance of YouTube to hide the identity of content providers, the representation of “The Presence” in this video deviates from others in some important ways. The first is the explicit reference to “Parepin.” “Parepin” is a plot device from the Year Zero narrative, and is a type of drug the government puts in the national water supply. According to the game’s wiki (“Parepin”), the purpose of “Parepin” is to protect the population against bio-terrorism by boosting the immune system, but many people feel that this is simply a pretext for using it as part of nation-wide program of sedation (“Parepin”). The wiki describes numerous additional effects of Parepin, and the wiki’s entry on “The Presence” infers a connection between “Parepin” and sightings of “The Presence” (“The Presence”). The video makes this connection for the audience with its reference, and posted under the name takeparepin. Furthermore, the questionable origin of the video is discussed by the community via YouTube’s commenting feature. Several users identify the original source of the video as an in-game website (TehDiz15; Justin Overdorf; darthkitty3), but others debate this claim (djGentoo; negativecreep654; 666Shadows666) and even go so far as deconstructing the method of production to validate their views (soweRESIST; 1theFRAgILe1; djtrixen). The discussion also includes debates regarding the relationship between “The Presence” and “Parepin,” thereby using the ambiguous nature of this relationship to explore the duality of this information (soweRESIST; bungbung13131; HairballandCo). It both reveals and obscures parts of the narrative (Krapp 39), and facilitates the “revealing noise” function and aesthetic.

Figure 2.2: Image captured form the “Parepin: What I Saw” video.

The affordances of digital media that facilitate the development and integration of user-generated content and pieces of fan fiction enhances the diegesis of Year Zero by anonymizing the roles of participants, thereby contesting the power relations implicit in conventional producer-consumer relationships. YouTube facilitates a “role-playing” function by allowing users to set up profiles, thereby enabling them to author their identities. This affordance at once reveals and obscures their relationship to the content, as it facilitates what Barthes (“Death of the Author” 1466) and Foucault (“What is an Author?” 1628) identify as the author function; that is, it helps shape the discursive meaning of a piece of information by anchoring it in an ontological concept. However, as YouTube’s reasonably open and accessible participatory structure enables virtually any digitally literate individual to assume this author function, ARG participants are fully aware of the need to critically reflect on information provided within the game. This includes challenging the meanings traditionally found within the author-function described by poststructuralists. Even though the author is identified by the YouTube user profile, the politics of digital discourse demand game participants challenge, investigate, and critically engage with the information.

The anonymous, amorphous power behind screen and keyboard, folder, file, client and server, code and compiler, and so on, never shows itself – or it shows itself only as such as the apparatus. Suspicion is a favorite mode of media theory because signs or images always both show and cover something (Krapp 38-39).

Krapp’s suggestion here not only reinforces the idea that all digital information functions as revealing noise, but that the political relationship between the user and the information is inherently shrouded. As a result, the identities of users who post these YouTube videos (whether it be an organization such as the USBureauofMorality) or the various commentators on the video (djGentoo; negativecreep654; 666Shadows666) are open for debate and challenge. In this contestability lies on of the greatest strengths of ARGs and their unique brand of play: the ability to democratize the authorial function to include the audience. By drawing attention to the potential of signs, information, discourse, and any type of communication to both reveal and obscure meanings, Year Zero provides a forum for participants to challenge the discursive power wielded by authority agents. Once players of the ARG recognize that the meanings of the game text are not anchored in a clearly definable agent, they are free of the epistemological constraints that govern their access, interpretation, and participation in the text. While such a realization may not conclusively demonstrate that the revolutionary potential of Year Zero will be realized, it does illustrate a dramatic shift in the power relations that typically govern the producer-consumer relationship. As Krapp points out “On intrapersonal and interpersonal levels, the secret assumes a pivotal function: to regulate access is to balance sharing and keeping” (40). Year Zero thus enables consumers to actively partake in the production, circulation, and control of the game’s discourse. By anonymizing the identities of game participants, the author function draws attention to the game’s meanings not as objects of consumption but of sites of politically contestable authority. Identifications of authority become signs that at once reveal power relations and their instability while hiding meaning, which can be challenged, co-opted, and re-appropriated through the use of digital platforms.

“The Presence” in Web Sites

As in most ARGs, Year Zero uses the Internet (and web sites in particular) as the primary resource to build its narrative. These websites include meta chat forums that help facilitate player coordination, in-game chat forums to allow them to interact with other characters and role-play, and web sites that help develop the diegesis of the game. Year Zero takes a unique approach to using these web sites, and designs them to develop the narrative and enhance the immersive aesthetics. In the Year Zero storyline, much of the information the players come across presents itself as being from the future, and sent back in time to warn the audience/players of the perils posed by the increasingly tyrannical government. As a consequence of sending the information back in time, it has been distorted or otherwise “lost,” thereby giving players only glimpses of the game’s “truth.” Most of the in-game websites design reflects this information degradation, thereby further developing this aesthetic of ‘revealing noise’ and using it to encourage player involvement. Inevitably, this helps enhance the game’s narrative develop as a conspiracy theory, with the nature of “The Presence” taking an important role. “The Presence” becomes a symbol for the presence of truth without actually revealing that truth, instead asking the player to simply believe that there is one.

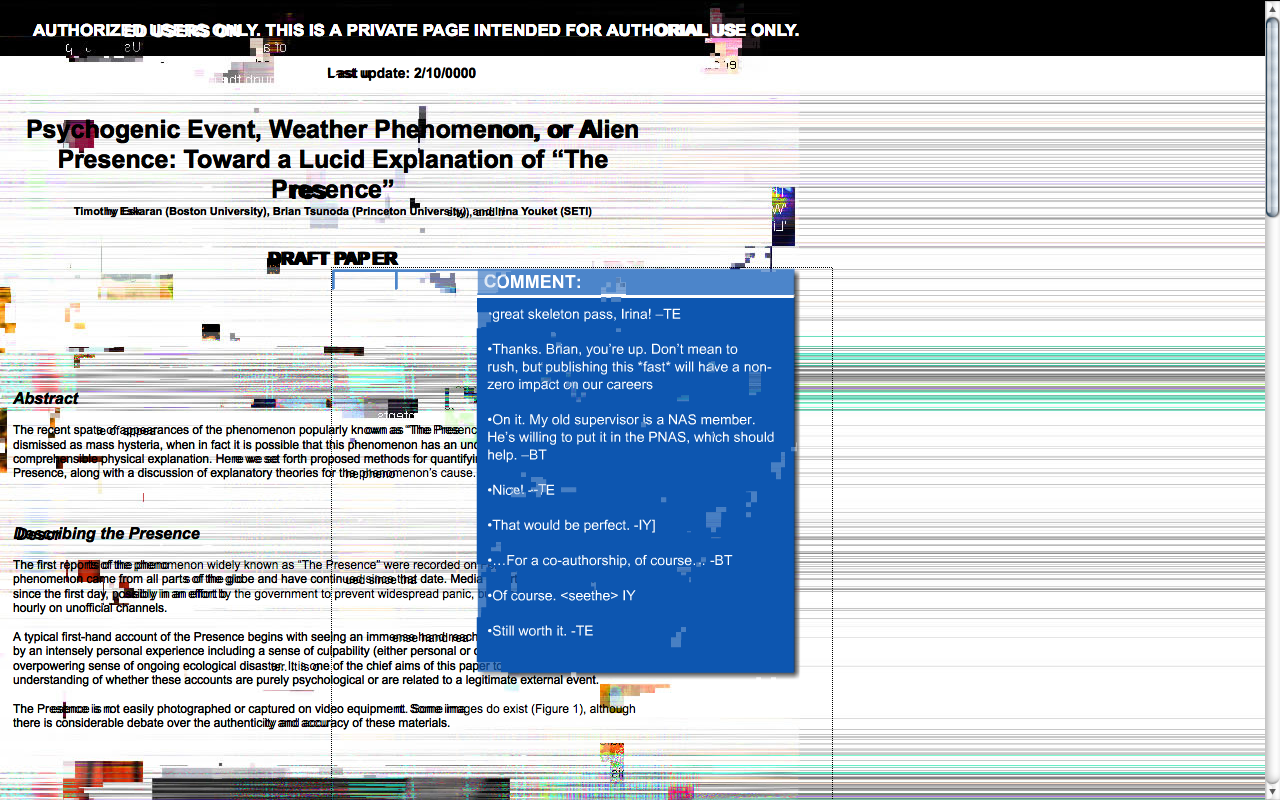

Brian Tsunoda and his colleagues (whose identities are partially hidden attempt to formulate a scientific explanation for the “The Presence” in their paper “Psychogenic Event, Weather Phenomenon, or Alien Presence: Toward a Lucid Explanation of ‘The Presence.’” 4 The paper was posted on Brian Tsunoda’s website (“Psychogenic Event”). As with all pieces of information sent back from the future in Year Zero, much of the paper’s content is distorted beyond readability, but it is clearly identified as a rough draft and includes comments from Brian’s “peers.” According to the abstract, its intention is to quantify sightings of “The Presence” and discuss some explanatory theories. It provides a description of the phenomenon, some factors commonly associated with its appearance, and an account of some of the empirical affects it carries (for example, traffic problems, power outages, etc). Finally, it discusses the theoretical causes of the phenomenon: specifically, potential psychogenic, extraterrestrial, and meteorological origins. The comments provide annotations from Brian, the co-author Tim, and an unidentified third person. Their remarks indicate their difficulty in obtaining cooperation from sources and Tim’s input as someone who has had a firsthand encounter with “The Presence.” This paper is important as it develops the mystery of “The Presence” and the difficulty of situating it within scientific discourse. Not only does “The Presence” challenge conventional scientific wisdom (as seen by the three different theories of its origin), there are also indications of a degree of bureaucratic resistance towards scientific inquiry in this matter. As the unidentified third party states in the comments: “VoxTelecom wouldn’t release cell phone figures either, even though they cooperated with me a year ago for a different project. There is definite resistance at the corporate level, and it appears to be specific to the Presence.” This remarks suggests that scientific inquiries are obstructed, leaving audiences to wonder why this is so, and the truth about “The Presence”. Of additional interest in the comments is the discussion of Tim’s encounter with “The Presence”, as it introduces the possibility of a religious explanation of the phenomenon, without attempting to address it scientifically. Tim himself maintains that his experience was inherently religious, and suggests the real question is “Was I dreaming—or was I waking up?”

Figure 3.1: A screenshot from “Psychogenic Event, Weather Phenomenon, or Alien Presence: Toward a Lucid Explanation of ‘The Presence.’”

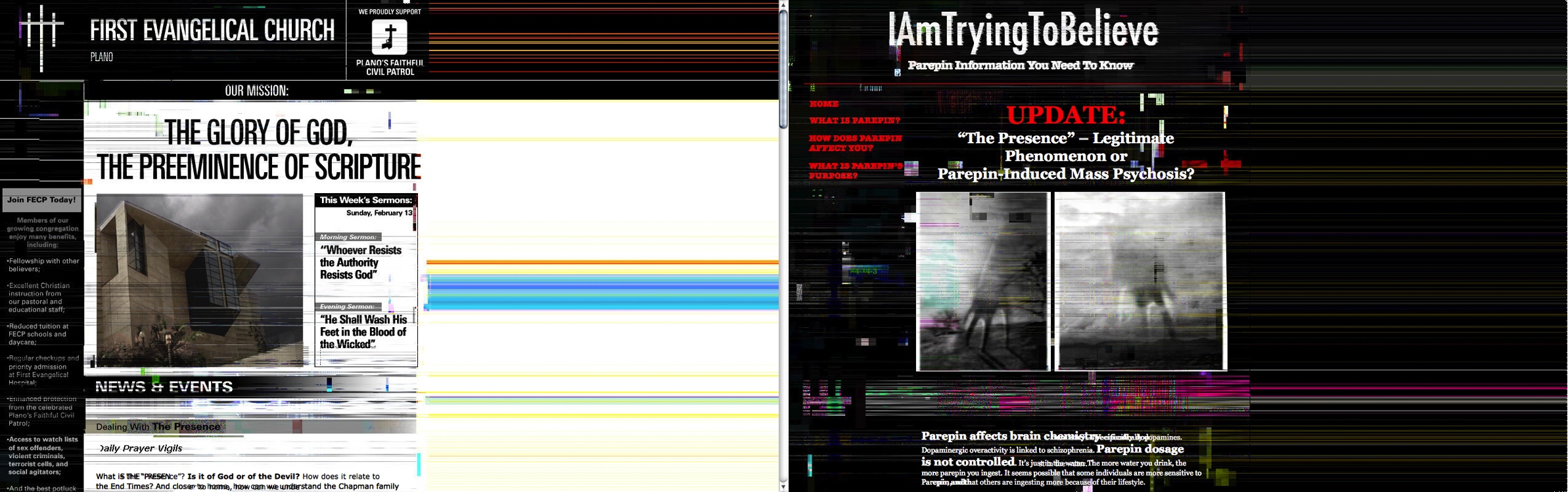

The apparent failure of science to provide a cohesive phenomenological account of “The Presence” enables the development of conspiracy theories, both inside and outside of the game’s diegetic framework. The answering of questions with more questions plays an important role in this, and the inexpensive and accessible medium provided by the Internet allows divergent perspectives to proliferate. Two such website within the Year Zero narrative are I Am Trying to Believe (“I am Trying to Believe”) and Church of Plano (“Church of Plano”). These two websites do not pretend to have scientific authenticity and do not attempt to provide a phenomenological account of “The Presence.” Their explanations attribute these sightings to mass psychosis and religion. The Church of Plano is a fictional church located somewhere in the United States, and addresses “The Presence” as something associated with divinity. Such a representation is important, as it furthers the idea that “The Presence” is associated with some kind of absolute truth, in a single, complete “oneness” that is systematically denied by scientific discourse. Beliefs of this sort are important to formulating conspiracies, as it allows believers to indulge in the idea that something will always remain out there for them to discover (Krapp 35.) I Am Trying to Believe offers a second interpretation of “The Presence” and suggests that it is a hallucination caused by the widespread use of the drug “Parepin.” The website follows the implication with a lengthy discussion of the insidious reasoning for the government’s distribution of the drug through the water supply, and what the actual effects of the drug are for the general population. While this idea negates the possibility that “The Presence” is “real,” such a denial is integral to the circulation of conspiracy theories, as denying secrets is in itself a type of validation (Krapp 34.)

Figure 3.2: Screen shot from churchofplano.com (left) and iamtryingtobelieve.com (right).

“The Presence” both symbolizes and denies a truth object in the game, thereby providing the semiotic resources to construct conspiracy theories. In so far as “The Presence” (and other elements in the game) function as “revealing noise,” they both obscure and confirm the existence of anchored meanings. By performing this dual function of what are seemingly contradictory epistemological functions, “revealing noise” provides game participants with the necessary preconditions to proceed with the formation of conspiracy theories or conspiracy theory like narratives. Based on the websites discussed above, it is clear that the creation of divergent storylines is an integral part of Year Zero’s diegesis. Several possible explanations of truths are postulated by a variety of sources, but audiences are not left with a clear resolution. Without such a resolution (or even a clear path to one), “The Presence” invites the formation of speculation, creation, and the development of a plurality of solutions to the problems it poses to the idea of a cohesive narrative. Krapp suggests that these characteristics place such play experiences in direct opposition with the idea of a central author (or authority) entity: “Version control, authentication, and data integrity are not among the core features of this structure; it is marked by hearsay, rumor, storytelling, which goes against the command-and-control efficiencies of the administration of power” (49.) According to Krapp’s assertion, by introducing the creative process as a meaning-making tool, meaning becomes detached and unstable, and inevitably prevents the formation of any sort of “regime of truth.” 5

By denying the establishment of absolute meanings, the “revealing noise” function of “The Presence” invites the creative interrogation that is conspiracy theory. Pieces of “revealing noise” establish the foundation that makes conspiracy theories possible, as they distort absolute meanings while simultaneously confirming their existence. For this reason, these symbols provide participants with the pretext for resolving the apparent contradiction through modes of creative inquiry, including forms of play. According to Krapp, conspiracy theories are at their heart processual (35): they are alternatives to common sense because common sense cannot maintain its cohesion when challenged by the kind of play practices fostered by new digital game genres such as ARGs (Krapp 77; Why I Love Bees 214). As seen by the various intertwining of the fiction presented by Year Zero with various real world social issues (religion, drug addiction, etc.), steganographic techniques (hidden messages, poetics), and non-traditional storytelling platforms (YouTube), playing the game inevitably becomes an exercise in maintaining the play experience by creating a balance between the desire for resolution and the pleasure created by the absence of the author (or more specifically, the authority/governing function the author represents). As demonstrated by the websites discussed above, “The Presence” facilitates this kind of creative theorizing. The websites postulate competing ideas that attempt to resolve the paradox “The Presence” poses to the audience, leaving the audience no choice but to continue the search for meaning via theorization:

Behind the message are technical devices (paper, film, computer); behind these are production processes, electricity, economy; and behind those we can suspect something else in turn…Behind all these technical setups lurks a political agenda. And so on. This conundrum of the dark side of the media is the eternal fountain of media theory. (Krapp 39)

Thus, “The Presence” symbolizes the existence of meaning, but does not identify the meaning to the audience, leaving them to theorize about the meaning behind the symbol. This meaning lies in what Krapp ominously refers to as “the dark side of the media”. While such a description betrays a somewhat sinister motivation, in Year Zero, such “revealing noise” is employed as a literary device to add depth and intrigue to the narrative, and provides an important symbolic component for the conspiracy theories in the game.

Conclusion

Year Zero’s use of “revealing noise” facilitates its unique mode of ARG play by encouraging audiences to process the game’s diegesis, and their relationship to it, as participants in a conspiracy theory. “The Presence” allowed users to explore the origins of the concept in a manner that gave them the freedom to speculate and create, but not in a way that permitted resolution to the paradox. In doing so, the game created a mode of play that invited participants to sustain critical engagement with the game, its concepts, and each other. This unique play experience facilitates the creation of conspiracy theories, as it demands critical examination without the possibility of resolution. This was seen in not only the representations and semiotic composition of the game, but also in the unique interactive modes and opportunities for collective engagement employed by Year Zero. By using media such as websites, user generated content forums, and other digital technologies, participants navigate the game’s text without relying on the conventions of traditional storytelling platforms. Without these traditional conventions, and the authorial function in particular, meanings in the game are contestable and open to democratic debate. By capitalizing on information as inherently flawed and incomplete communication messages, Year Zero uses both the alpha and omega channels in signals as diegetic resources.

Year Zero provides an excellent example through which the ability of ARGs (and presumably other similar types of digital works) to contribute culturally and socially relevant works can be discussed and debated. This analysis highlighted several practical and theoretical concerns posed by Year Zero to guide future research. One such issue is questioning the social value of conspiracy theories, and the processes that create them. Such an issue has a long tradition in academic research through its indirect association with myths. For example, Roland Barthes could have been talking about “The Presence” from Year Zero when he discussed Einstein in Mythologies:

There is a single secret to the world, and this secret is held in one word; the universe is a safe of which humanity seeks the combination. […] In it, we find all the Gnostic themes: the unity of nature, the ideal possibility of a fundamental reduction of the world, the unfastening power of the word, the age-old struggle between a secret and an utterance, the idea that total knowledge can only be discovered all at once, like a lock which suddenly opens after a thousand unsuccessful attempts (1463).

Many of these issues were touched upon in this analysis of “The Presence”; the mystery and intrigue surrounding this phenomenon took root in the web pages, videos, and comments that composed the game’s diegesis. The lack of resolution regarding the phenomenon echoes the unanswered questions connoted by Einstein’s brain. However, this analysis did not attempt to make a claim that “The Presence” or any part of Year Zero represented a modern myth. Much of this has to do with the politics of digital discourse phenomena. As Krapp discusses, the employment of “revealing noise” in digital discourse integrates itself into digital communities, and in doing so politicizes its relationship outside of its particular ontological conditions:

If technology is the genesis of secrecy, then access to concealed knowledge is possible only in breaking the illusion that positions this object outside discourse. This veiling mode of controlling access is sheer power, its necessary side effect is the desire to preserve the identity of the secret and yet know about it at the same time. The pivotal moment must be at the same time withdrawn and displayed, concealed and known. This, in a nutshell, is the dynamic of groups organized around a techno-fetish. What is really at stake in sifting through information, screening, scanning the reserves of storage, and packet-switching behind multiple screens is the articulation of a certain deferred revelation. The group psychological meaning of secrecy is a relation between knowledge and ignorance: as the group configures its group dynamics around a secret, its cohesion depends on the maintenance of an illusion (42).

In this lengthy passage, Krapp illustrates that digital technologies and the types of discourse that find growth in them essentially segregate themselves from anything outside its discursive regime. If one accepts that conspiracy theory is finding itself rooted in digital discourse, the truth object pursued by these theorists will forever remain outside of their knowledge, as that is the only way for the interested parties to sustain their discursive activities. Their very existence relies on the continuing promise of a revelation that would destroy its raison d’être. Thus, conspiracy theories create their own self-destruct mechanism, and ensure they remain safely relegated to the confines of the Internet. While myths evolve and become meaningful social objects, conspiracy theories stagnate and become digitally born Ouroboros, and have the potential to ensnare the democratic potential of digital discourse in its cycle (Krapp 28).

These theoretical concerns provide a touchstone for future research on both ARGs and emerging forms of digital aesthetics and discourse. While it is difficult to say with any assurance what the future holds for digital works such as Year Zero, ARGs have demonstrated themselves to be capable of producing meaningful narratives and ludic experiences. Even though Year Zero has been inactive for a number of years, fans of the game and its artists still talk of the possibility of a sequel or some kind of new content (rumors persist of a possible television project.) New ARGs are constantly produced and used to market products, crowdsource creative works, or facilitate various sorts of social marketing goals. It is important to note, as other academics have pointed out, that these games are overwhelmingly used to facilitate social marketing objectives (Ornebring 450). Contrasting these very accurate and very relevant pieces of research with this discussion introduces serious questions about the legitimacy or authenticity of these aesthetic experiences, and is a direction of research that I (for one) will be pursuing in the future. This analysis is not meant to diminish or even necessarily outright refute these concerns. Rather, it is hoped that this discussion will force researchers to consider why people are tuning out of reality based media and finding the alternate realities of the digiverse a much more engaging and enriching communication experience.

Works Cited

42 Entertainment. Year Zero Case Study. 42 Entertainment, 2008. Web. 14 April 2012. http://www.42entertainment.com/yearzero/

Barthes, Roland. “The Death of the Author.” The Norton Anthology of Theory and Criticism. Ed. Vincent B. Leitch. New York: W.W. Norton & Company Ltd., 2001. 1466-1470. Print.

Barthes, Roland. “From Work to Text.” The Norton Anthology of Theory and Criticism. Ed. Vincent B. Leitch. New York: W.W. Norton & Company Ltd., 2001. 1470-1475. Print.

Barthes, Roland. “Mythologies.” The Norton Anthology of Theory and Criticism. Ed. Vincent B. Leitch. New York: W.W. Norton & Company Ltd., 2001. 1461-1465. Print.

Church of Plano. Church of Plano. n.p., 2009. Web. 14 April 2012. churchofplano.com

Derrida, Jacques. “Dissemination: Plato’s Pharmacy.” The Norton Anthology of Theory and Criticism. Ed. Vincent B. Leitch. New York: W.W. Norton & Company Ltd., 2001. 1830-1876. Print.

Dombrowski, Caroline, Jeffrey Kim, Elan Lee, and Timothy Thomas. “Storytelling in New Media: The Case of Alternate Reality Games, 2001-2009.” First Monday 14.6 (2009): n.pag. Web. 8 June 2011. http://www.uic.edu/htbin/cgiwrap/bin/ojs/index.php/fm/article/view/2484/2199

Nielsen, Simon-Engenfeldt, Jonas Heide Smith, and Susana Pajares Tosca. Understanding Video Games: The Essential Introduction. New York: Routledge, 2008. Print.

Foucault, Michel. “Truth and Power.” The Norton Anthology of Theory and Criticism. Ed. Vincent B. Leitch. New York: W.W. Norton & Company Ltd., 2001. 1667-1670. Print.

Foucault, Michel. “What is an Author?” The Norton Anthology of Theory and Criticism. Ed. Vincent B. Leitch. New York: W.W. Norton & Company Ltd., 2001. 1622-1636. Print.

Hall, Alex. “A Way of Revealing: Technology and Utopianism in Contemporary Culture.” Journal of Technology Studies 35.1 (2009): 58-66. Print.

I am Trying to Believe. I am Trying to Believe. n.p., 2009. Web. 14 April 2012. iamtryingtobelieve.com

Jenkins, Henry. “Transmedia Storytelling 101”. Confessions of a Aca-Fan: The Official Weblog of Henry Jenkins. Henry Jenkins, 2007. n. pag. Web. 22 April 2012. http://henryjenkins.org/2007/03/transmedia_storytelling_101.html

Krapp, Peter. Noise Channels: Glitch and Error in Digital Culture. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2011. Print.

McGonigal, Jane. “A Real Little Game: The Performance of Belief in Pervasive Play.” Jane McGonigal.com. Jane McGonigal, 2003. n. pag. Web. 3 Dec. 2011. http://janemcgonigal.files.wordpress.com/2010/12/mcgonigal-a-real-little-game-digra-2003.pdf

McGonigal, Jane. “This is Not a Game: Immersive Aesthetics and Collective Play.” Digital Arts and Culture 2003 Conference Proceedings. Melbourne Digital Arts Conference, 2003. 110-118. Web. 22 April 2011. http://hypertext.rmit.edu.au/dac/papers/McGonigal.pdf

McGonigal, Jane. “Why I Love Bees: A Case Study in Collective Intelligence Gaming.” The Ecology of Games: Connecting Youth, Games, and Learning. Ed. Katie Salen. Cambridge: MIT Press, 2008. 199-228. Web. 16 April 2012. http://www.mitpressjournals.org/doi/pdf/10.1162/dmal.9780262693646.199

“Nine Inch Nails - Year Zero – Teaser Trailer.” YouTube. YouTube. 14 April 2012. Web. 14 April 2012. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-Ori4KGvRoY&feature=related

Ornebring, Henrik. “Alternate Reality Gaming and Convergence Culture: The Case of Alias.” International Journal of Cultural Studies 10.4 (2007): 445-462. Print.

Pacey, Arnold. “Technology: Practice and Culture.” Controlling Technology: Contemporary Issues. Ed*.* W. B. Thompson. Buffalo: Prometheus, 1991. 65-75. Print.

“Parepin.” The Nine Inch Nails Wiki. N.p. April 29. 2012. Web. 21 May 2012. http://www.ninwiki.com/Parepin

“PAREPIN: What I Saw.” YouTube. YouTube. 14 April 2012. Web. 14 April 2012. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GBf2gyCT_qY

Powers, Ann. “Nine Inch Nails creates a world from ‘Year Zero.’” 17 April 2007. Internet Archive. Web. 14 April 2012. http://web.archive.org/web/20070625205704/http://www.calendarlive.com/music/reviews/la-et-nails17apr17,0,817496.story?coll=cl-albumreviews

Reznor, Trent. “The Warning.” Perf. Nine Inch Nails. Interscope, 2007. CD.

Rushe, D. “Pacific trade pact boost for Obama - but China remains cool.” 14 November 2011. The Guardian. Web. 14 April 2012. http://www.guardian.co.uk/business/2011/nov/14/pacific-trade-pact-china-obama

Simonowski, Roberto. Digital Art and Meaning: Reading Kinetic Poetry, Text Machines, Mapping Art, and Interactive Installations. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2011. Print.

“The Presence.” The Nine Inch Nails Wiki. N.p. April 29. 2012. Web. 21 May 2012. http://www.ninwiki.com/The_Presence

“‘The Presence’: Psychogenic Event, Weather Phenomenon, or Alien Presence?” Brian Tsonuda. n.p., 2009. Web. 14 April 2012. http://www.briantsunoda.com/

“USBM Leak: The Presence.” YouTube. YouTube. 14 April 2012. Web. 14 April 2012. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bqucAwTQe9A

The Webby Awards. Webby Nominees. International Academy of Digital Arts and Sciences, 2008. Web. 14 April 2012. http://www.webbyawards.com/webbys/current.php?media_id=98&season=12

Footnotes

-

Play is used here within Derrida’s understanding of the concept: “its very presence lays it open to to some sort of dialectical confiscation” (1867). ↩

-

Most of the information pertaining to the game, including instructions on how to navigate the game, were taken from the Year Zero Research Wiki (http://www.ninwiki.com/Year\_Zero\_Research). ↩

-

“Fan fiction can be seen as an unauthorized expansion of these media franchises into new directions which reflect the reader’s desire to “fill in the gaps” they have discovered in the commercially produced material” (Jenkins.) ↩

-

The co-authors given name is Timothy and works at Boston University. He is mentioned in the comments that are littered throughout the paper, and the commentator is identified only by the initials I.Y.) ↩

-

A “regime of truth” is defined by Michel Foucault as systems of power which produce and sustain truth, which itself is defined as “a system of ordered procedures for the production, regulation, distribution, circulation, and operation” (“Truth and Power” 1669.) ↩

Cite this essay

Pilkey, Adam. "Revealing Noise: The Conspiracy of Presence in Alternate Reality Aesthetics" Electronic Book Review, 22 January 2013, https://electronicbookreview.com/publications/revealing-noise-the-conspiracy-of-presence-in-alternate-reality-aesthetics/