Room for So Much World: A Conversation with Shelley Jackson

Rettberg's and Jackson's interview, and their creative work's direct engagement with environments anticipate the themes in a forthcoming ebr gathering by Eric Rasmussen and Lisa Swanstrom, titled Natural Media. More than just an articulation of environmental 'issues,' the creative work of Jackson and Rettberg actively integrates snowfall in Brooklyn, tattooed skin on bodies, pollutants in Jersey City and New Orleans (post-2012), and other particles and particulars that are touched by natural and medial ecologies.

This conversation is published as the fourth in a series of texts centered around the publication of The Metainterface by Søren Pold and Christian Ulrik Andersen. Other essays in the series include: The Metainterface of the Clouds, Always Inside, Always Enfolded into The Metainterface: A Roundtable Discussion. and Voices from Troubled Shores: Toxi•City: a Climate Change Narrative.

Q: Shelley, the idea of doing this interview arose from a kind of cluster of texts we’re publishing in ebr built around Søren Pold and Christian Ulrik Andersen’s The Metainterface, a work that calls for a reconsideration of interface studies, essentially shifting its focus from the ways that interfaces shape the interaction between humans and software, or on questions of interface usability, to the way that technologies and interfaces now actually shape human behaviors, human society, and even the environment of the planet in a broader sense. In a chapter titled “The Cloud Interface: Experiences of a Metainterface World,” Pold and Andersen read the environment itself as a metainterface, shaped to an increasing degree by our interactions with technology. They focus there on two works in particular, the combinatory climate change narrative film Toxi•City that Roderick Coover and I produced, and your work “Snow.” I thought I’d kick the interview off by asking a few questions about “Snow” before moving on to your new novel Riddance (Black Balloon Publishing, 2018).⏴Marginnote gloss1⏴A similar deconstruction of Western individualism can be found in an essay by Babak Elahi in an ebr gathering of essays from the Electronic Literature Organization conference in Dubai (2017).

— ebr Editor (Dec 2018) ↩⏴Marginnote gloss2⏴See George Landow’s ebr review of Jackson’s “actual” hypertext, Patchwork Girl.

— ebr Editor (Dec 2018) ↩

On “Snow”

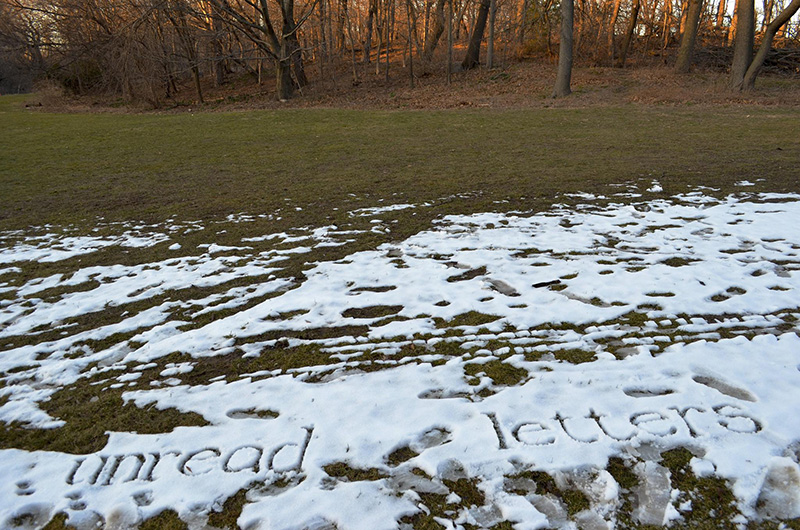

“Snow” is “a story, weather permitting” that you are drawing, one word at time, literally in the snow. Your process here, as I understand it, is that you have taken this story you wrote a long time ago, and you are now hand-publishing it one word at a time, on occasions when it snows in your neighborhood in Brooklyn. You have published an archive of photographs of these words on Flickr and on Instagram, which as Pold and Andersen point out, is a gesture of returning the snow to “the clouds.” This is your second one-word-at-a-time project, after your 2003 project “Skin, a mortal work of art,” which was composed of a couple thousand words tattooed on the skin of volunteer “words” who agreed to wear your text for the rest of their lives in exchange for the full text of your story and your promise, to the best of your ability, to attend their funerals.

By the way have you been to any of their funerals yet? And if so, what was that like? Did you have interesting conversations with any of the mourners? Have all the words survived?

SJ: No, I haven’t been to any funerals yet, but I have been informed by family members of the deaths of a few of my words. It’s a strange and solemn thing. Any death is that, of course, but my intimate-yet-distant relationship to my words makes these deaths particularly strange for me. I have a bodily involvement with my participants, and they with me, but at the same time I don’t truly know them. I did write a poem for one of them, to be included in a collection of memorial tributes. I spun it out from the word he had been tattooed with, and that made me feel even more clearly that my story was bound to him, his particular life, and that part of it went with him to his death.

Q: Both “Skin” and “Snow” are fascinating for their play between image and text, and text and bodies. There’s a lot of interstitiality here: a text that is also an image, also a material object, also a performance, emphasizing the in-between-ness of word and image, of text as a symbolic representation of meaning and as a physical artifact, of letters and utterance.

You are a very precise writer, and you often revel in linguistic play and the expressive potential of florid language. You are also a visual writer and illustrator. I have never had the sense in any of your work that you are simply treating words as a material like paint or clay or whatever, but I’m wondering if you could say more about these layers of interstitiality? Is there any difference between reading text and interpreting visual art? Do you think these kinds of works fire on multiple semantic registers?

SJ: Yes, absolutely. In both projects I mean to push awareness of the materiality of the written word so far that it slows the leap to denotative meaning way down, and at the same time complicates that meaning by inviting all sorts of intrusive extra associations, many of them bodily, tactile. It’s a deliberately impure way to write. I don’t believe in purity—don’t believe it exists, and don’t value it as an ideal either. But I don’t mean to eradicate distinctions between reading and visual art, say—to imply that they’re the same would be to aim at another kind of purity, I think. There’s clearly a difference, both between the two kinds of looking involved in reading and viewing art, and between the two art forms. But I’m interested in the somewhat awkward, sticky space between the two, the problem you might have deciding whether the look of specific words in “Snow”—or the way I’ve framed them—or objects that might be in the frame—are just visual noise surrounding the story, or at the heart of the piece. Or deciding whether the work consists of the photographs, or of the words actually written in the snow, or of what happens as I create them. I don’t mean to answer the questions, only make both story and images rich enough that it’s rewarding to ask yourself them. This also involves letting go of what happens to my story—controlling less of how the reader encounters it than most writers are willing to do. In the case of “Skin” I quite literally cede the investiture of meaning in my story over to my readers, who are also my participants, and those they allow to be their own readers, i.e. those to whom they show their tattoos.

Q: I have the impression that “Snow,” like many of your projects, is one that you live with for a long time. It doesn’t snow every day in Brooklyn. And you don’t simply scrawl these words into the snow. It looks like you spend a lot of time with each letter. The words look like they are printed into the snow. I’m not quite sure how to phrase this, but when I look at these images of words, I think about duration, about time. There’s the fleeting—the mortality of the words in “Skin” and even more so the ephemerality of the snow—but these are also projects that you wait for. They unfold over a long time. And as an author you’re waiting for the snow, a factor is that is completely out of your control. Is there something about this different kind of life cycle that attracts you to these projects?

SJ: It is slow. Every winter I can only do, say, a paragraph. Each word takes a long time—each letter takes a long time. My fingers and toes go numb. (One winter I caught pneumonia!) The slow handiwork is part of the interest, for me; it’s interesting in its own right as some kind of messed-up combination of calligraphy and engineering, but also for the perversity of doing such painstaking work on something that will be gone almost as soon as I finish it. The perfecting of a skill that is useful only for this one project—or even only for this one word, since each patch of snow is a little different, melting at a touch, or cracking, or blowing away. The quixotism of attempting precision in such a shifty and ephemeral medium. There’s a relationship to mortality that is made quite literal in “Skin,” an awareness of our human condition as similarly perverse and poignant—absolute commitment to our personal program of being in the world despite knowing that we dissolve in the end.

Maybe if it were physically possible to write the words faster, I would have finished the project over the course of one winter, without thinking about the merits of taking it slow. But as it happens, I love this pace that makes room for so much world. I mean, distributing a story in space is one way of inviting the world into it. Spreading it over time is another. This way I get both.

Q: I did a project with Nick Montfort back in the 2000s, a sticker novel called Implementation. The novel was about America changing and adjusting to a new kind of security-driven state after the 9/11 attacks. It was composed of small narrative segments that each fit on a business-sized shipping label. We sent those out to readers, who then placed them in public environments, and photographed them, and sent them back to us. One of the surprising things to me about my own reaction to the project, and the reason I bring this up in the context of “Snow,” is that I ended up spending much more time placing and photographing the stickers than I had writing the texts themselves. The process of doing this became part of my routine, for a good long time. Maybe part of the attraction was that it was kind of transgressive, placing these stories in public places. Maybe it was about making something private public, or in some way making writing a part of the mundane world. But it also made me look at the world around me, the cities I visited, in a completely different way. By placing these texts, I started seeing new things in the world around me. I wonder if this project has had a similar effect on you? Do you see Brooklyn differently? Do you have a new experience of snow days?

SJ: Yes, absolutely! I will never see snow the same way, for one thing, and not just because I reimagine it in my story, but because what it actually is has, what, quickened for me. I notice it, it matters: bird tracks, tire tracks, the little clearing around each salt crystal.

These projects that put writing out into the world (and “Skin” is one of these too) also revise the world a little, by linking specific places and objects to a story. Maybe it’s an extension of childhood games of pretend, when you could make ordinary places extraordinary without changing anything but how you thought about them. It’s like I’m issuing a general invitation to play. And of course snow is practically for playing in. So it’s probably not surprising that I get the most public attention from kids (“from other kids,” I almost said), who want to know what I’m doing, and to try it themselves, and to stomp through it. Even before I’ve finished, sometimes. Oh, and from dogs, too. They might not get the story, but they get the invitation. They want to play!

Q: When I was preparing for this interview, I looked through the whole archive of “Snow” photos you have posted to date (which as I understand is so far about half of the story as a whole). I noticed that when I was looking through the photographs as images, I was reading them, but I was reading them one word at a time. I was reading the relationship between the single word and its environment. And that’s certainly compelling in its own right. But I noticed that I couldn’t really parse them into lines or a connected whole at the same time. So I went through the images one at a time and typed the words into a text document. It was only then that I could read the prose as prose, as connected lines. There was a process of decoding involved. And as I think about it, it occurred to me that this process is a lot like how we construct memories or narratives of our experience. The moments each have this kind of singularity and aren’t necessarily connected at the time that we experience them. It’s afterwards that a process of decoding takes place. Does that make sense? Is there something about the way that this process unfolds that you would connect to the construction of narrative or memory?

SJ: That’s so interesting. I think I’m actually deliberately impeding the construction of narrative. I’m isolating each word, allowing it its full resonance, the full range of meanings it can have, which is usually curtailed by its function both in the sentence and in the story as a whole. And then adding even more individual presence to that word by complicating it with visual, tactile, temporal, locational, meteorological specifics. Both narrative and memory have a tendency to smooth over the gaps between these “singularities.” But part of the work of literature is to resist this operation. To give the reader, not the story memory tells, but the raw material whose meaning we haven’t yet decided.

Q: The text of “Snow” (so far) comprises a kind of beautiful and strange prose poem that begins with the line “‘To approach snow too closely is to forget what it is,” said the girl who cried snowflakes.” The lines that follow describe many kinds, or rather many perceptions, of snow. What’s most interesting to me is that the kinds of snow you describe are not really about the types of subtle linguistic distinctions that, say, Eskimos or Norwegians use to distinguish fluffy powder from hail or sleet. Instead the lines are really doing a kind of phenomenology of snow. These snows for example include “the shattered breath clouds of those who have cried out for help unheard on a clear winter day” and “cerebral snows that, sifting along surfaces, seek knowledge of the countless forms of the world.” It seems that you’re considering snow as kind of generator of affect, or maybe as a way of framing human experience?

SJ: Obviously I’m not describing snow as it really is (though, interestingly, in the process of making the letters I am deeply, deeply involved with and aware of snow as it really is). I guess I’m trying to free the word snow from its more familiar associations in order to open it up to other ones. Each image gives way to another, melts or blows away. So I’m thinking about the temporary and mercureal nature of things—of snow, of ideas and feelings, of people. And how strange these things are that we think we know.

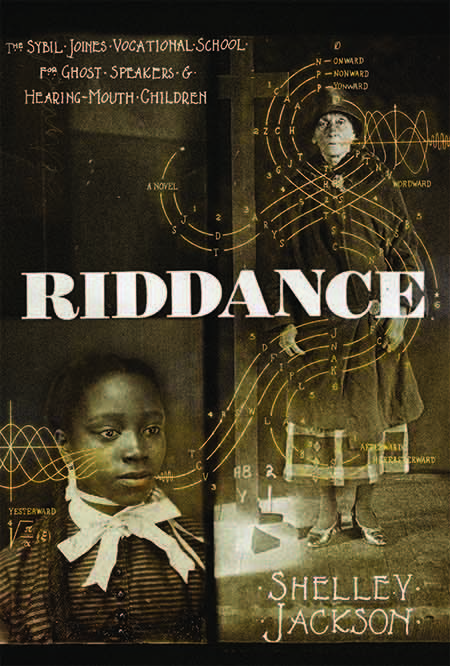

On Riddance: Or, The Sibyl Joines Vocational School for Ghost Speakers & Hearing Mouth Children

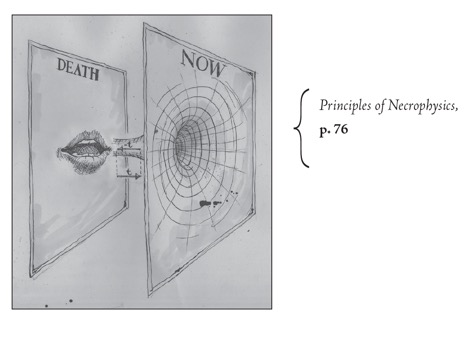

Q: Shelley, we are doing this interview shortly before the October 2018 release of your new novel, Riddance: Or, The Sibyl Joines Vocational School for Ghost Speakers & Hearing Mouth Children. I just had the pleasure of reading the book, and first of all I want to congratulate you on the book. This is a major work. I’ve followed your career from Patchwork Girl forward and read most of what you’ve published. This is clearly the magnum opus of your career, so far. This is a very substantial work, a 500-page novel that deals with themes ranging from the nature of language and writing to metaphysics and necrophysics. You play a great deal with a variety of literary conventions and styles, literary history, and explore relationships between memory and imagination, education and abuse, death and desire. Along the way, you create a strange universe of your own devising, set in the peculiar environs of a boarding school for stutterers that serves a double purpose as an oracular training ground, for the students in stuttering communicate the voices of the dead. The book is a multilayered neo-gothic voyage into an absurd but internally coherent world. I enjoyed the novel very much.

My first question about Riddance is about the seeds of the ideas for the book. In preparing for this interview, I re-read an interview we did about a dozen years back, and you were clearly thinking about some of the themes that long ago. Can you tell me about some of your sources of inspiration?

SJ: I think the ultimate point of origin lies in my childhood when at about the age of nine, two things happened simultaneously: I began keeping a journal, and my latent shyness intensified into a debilitating fear of speaking in front of strangers. The less I spoke, the more I wrote, and look what happened. So what held me back became my way forward. That paradox is at the heart of Riddance.

Looking back at my body of work, though, I can see many precursors of the obsessions that drive Riddance. One recurring theme is the elastic ligament between material thing and idea: the word and its meaning, the body and the self. Books, the way they seem a little bit alive. Bodies, the way they seem a little bit dead. I’m interested in how the spirit comes into the machine, you might say, where the machine might be the body or the page or a metaphysics haunted by personal trauma.

Another recurring obsession is with the ambiguous boundaries of the self, so porous to or simply made up of outside influences. The sense that there is no original self, only this composite, this collage. Look at Patchwork Girl. In this book, the composite is made of voices, not flesh, but it’s still a way of interrogating the integrity of the self. What are we if everything we are made of was first part of something else, and later on, will be part of something else again?

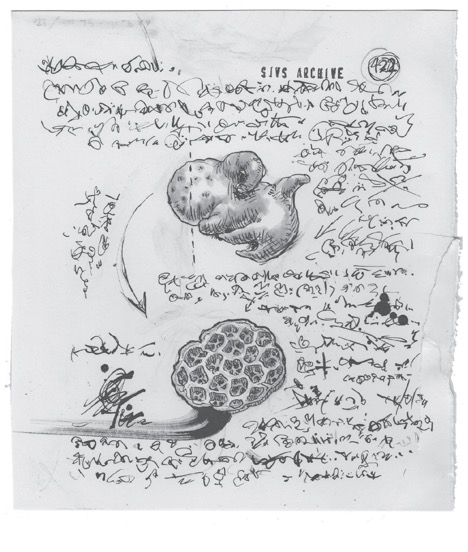

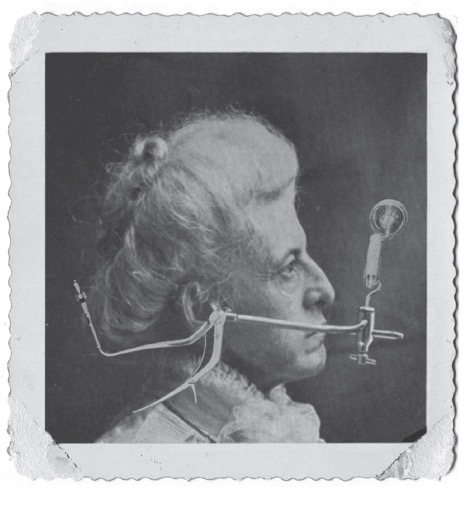

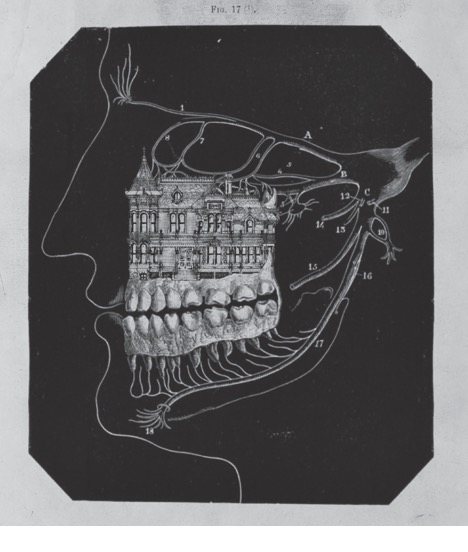

Q: One feature consistent across much of your work, which we considered a bit in the discussion of “Snow” in the first part of this interview, is an ongoing exploration of how images can be used in conjunction with texts to communicate stories in a different way. I’d like to follow a few threads along that vein. This book includes many images: doctored photographs and drawings, maps and diagrams, facsimiles of letters and telegraphs, asemic writing, medical documents, illustrations of exercises, musical notes and teaching materials. This is a hefty novel, but it is also in a way a work of visual art, an artist’s book. Why did you choose to include such a diverse array of visual material in the book, and how do you think it extends the sense of a world that the novel generates?

SJ: If I could have included sound and smell too, I would have. And recipes and calisthenics and homework assignments. I wanted to create, not just a story, but a three-dimensional world, a place one could live, or at least mistake for a backwater of the place where one actually lives. That the visual elements look plausibly historical, and some actually are, adds another dimension—I’m not just rewriting the present, but the past.

Then too, I’m interested in how and what mute things communicate, especially in literature: the blank page, the black page (Sterne), the weight and smell and tooth of the paper. Every book is, not just a vehicle of meaning, but a bit of world. It butts up against you directly, commanding a response, but not an interpretation as such.

Q: These image-texts and the nature of the sections of writing themselves (stenographic transcripts, letters to the dead, memoirs) construct a sense of exploring an archive, and so place the reader into the role of investigator or historian, sorting through an archive of materials to draw their own conclusions, or even construct their own narratives, from the materials you provide. I would also imagine, on the basis of things like the photographs that you repurpose and modify, that you actually spent quite a bit of time in archives yourself as you were developing this world. Can you comment on the role of archives, both as a structuring principal and a source of artistic research during your work on this project?

SJ: Long before I began Riddance, I was collecting old books on what you might call technologies of language: books on language learning and stuttering and oratory and shorthand and spirit mediumship and dentistry and voice training and ventriloquism and sound recording and writing automata and AI speech programs and teaching parrots to talk. You could say that writing Riddance was an attempt to draw a figure that bound together all those elements. Of course at a certain point in a project you no longer need to connect the dots. Putting them next to each other is enough. And then they no longer even need to be next to each other; if you work long enough on a book it starts writing itself off the page, into the larger world. You pick up an old manual of orthodonture in a thrift store and it seems to come right out of the SJVS archive. So the book is less a story than a sensibility, one you can take with you out into the world to re-constellate your reality, binding old elements into a new figure.

As a structure, the archive gives the sense of a recombinant text; also, one that is only arbitrarily limited, that could go on. It extends beyond its edges, by implication: other material could have been included, other material “exists.” In its artifactual quality it also extends into the “real world”, makes the distinction between real and fictional blurry. The photographs help with that too.

Q: Although this is a print book that is deeply engaged with the materiality of print, it is also very much a multimedia novel, and I think in its nodal structure has a lot in common with some of your digital works such as Patchwork Girl, My Body & a Wunderkammer, and The Doll Games. I’d even go so far as to describe it as kind of print hypertext in the sense that the reader is constantly drawing new connections between different kinds of material presented that extend and provide multiple perspectives on the core story. Did your early experience as a writer in digital media shape the way that you think about writing and storytelling in a more general sense?

SJ: I think you’re right to call it a print hypertext, but I also was unsure until quite far into the project whether its ultimate form might not be an actual hypertext. I wanted to present it as an academic website with historical material and study guides for distance learners. So the book didn’t begin with a story and then expand into these curious pieces of “fake nonfiction” that are interspersed among the more plot-driven portions of the book. It was the other way around. My original interest was in developing this alternate history, science, metaphysics into a sort of alternate but parasitic reality that I could launch into the internet free of the signifiers that clearly mark the print book as a work of literature, so that readers would encounter it as a plausible though absurd bit of the real world, rather than necessarily a work of fiction. The internet already blurs the boundaries between fact and fiction, in ways that are not always good. There’s a value to affirming the truth that our felonious president reminds me of every day. But there’s also a value, in a world inevitably fictionalized, of inserting some fictions of your own.

However, as I worked on those elements, I found little threads of story forming. The voice I was, let’s say, channeling, began to hint at a history. I was ambivalent about that, because it seemed to me that as soon as I introduced a plot, it would demote everything that surrounded it; readers would regard the fake nonfiction stuff as filler or ornament to the plot, rather than allowing it equal weight. When I committed to the story, it was with the hope that I could find a way, by ducking and weaving in and out of these different elements, to give all of them their due. And my sense of how to do that was very much informed by my work in digital media, which helped me think of a story as constellation of related elements rather than a line.

Q: While I was reading the novel, I thought often of your recurring interest in the Wunderkammer—the cabinet of curious objects, representing interests and obsessions particular to the individual collector. In a way the character of Sibyl Joines’s father represents this kind of eclectic and obsessive collector. I wonder if you have any thoughts on the nature of author or artist as collector?

SJ: Since I was a kid I’ve loved the idea of the Wunderkammer. I had my own small Wunderkammer as a kid, of things I had found (a rabbit’s tail, a rattlesnake’s rattle, a clump of quartz crystals), and I still have one today: a collection of objects that don’t serve, as in a science museum, as exemplary types illustrating abstract principles, but as sui generis objects of wonder, dream prompts, provocations. Things, in and for themselves. The relationships among those things are left to the viewer’s conjury; there is, there must be, some hidden figure that binds the constellation together, but it’s idiosyncratic, not generalizable, bound to those objects in particular, so you don’t get to leap over the specific weirdness of this, say, old china doll, in order to arrive at an abstract message. And this is how fiction works, too: it’s a language of images in which the meaning is not abstractable, in which the images mean themselves first, even if they hint at other meanings beyond themselves. My ectoplasmoglyphs could be read as an attempt to separate meaning from language, in order to allow it to be rather than to mean, or to mean, if it means anything, only itself.

The artist as collector: yes, in the sense of the Wunderkammer. I think that stories arise out of the interrelations of curiosities rather than the obsessive pursuit of any given one. I’m interested in ventriloquism, for instance, but not in reading everything about it or learning how to do it; I have one vintage ventriloquist’s doll, but I’m not interested in getting more, or finding out the provenance of the one I have. What I’m interested in is what’s both charming and unnerving to me about it, and how that relates to other things that interest me: little girls playing with dolls, for instance, and the characters writers speak through, the ambiguous life of inanimate objects and the ways we flirt with shifting our sense of self outside ourselves.

Q: There is a great deal of “orchidaceous” (by the way, thank you for that word) linguistic play in the book, and a great deal of dark comedy, but you are also tackling some serious issues here. There is a lot of trauma in this book, particularly in the sense that there is a great deal of cruelty towards children: child abuse. Sibyl Joines, one of the two main characters in the books, is abused horribly by her father, and she in turn goes on to found a school in which the children are also not only neglected, but used as a kind of technology, and even sometimes, for lack of a better word, murdered, as part of the experiments conducted at the school. While this is not an “issue” novel, I think it reflects real concerns, or real fears. Can you say something about this balancing act in a novel that on the one hand produces some scenes that are laugh-out-loud witty fun, and others that reflect quite deeply the nature and effects of abuse and trauma?

SJ: Ghosts, we know from books, are created by trauma—the murder victim, say, who can’t move on until she tells her story. Trauma creates an imprint that lasts. And this is true, right? What hurt you as a child can come back, years later, to hurt you again. We’re all haunted, we’re all time travelers, in that our past comes back. And in the worst cases it comes back over and over, for generations. Your childhood trauma becomes your child’s trauma, and the distinction between yourself and your child is blurred as you replicate the abuse you yourself suffered. So the ghost is not just a fading memory but a fully present, material reality. The headmistress is admirable in raising an edifice of original thought on the holocaust of her childhood, finding the way to make something of value out of unthinkable pain. But what is best about Sibyl Joines is not distinct from what is worst: the compulsion to make others suffer the way she did.

Q: The children at the school are all stutterers, and the novel could in fact be read from the standpoint of disability studies: it certainly illustrates how people who are born with disabilities are often othered and ostracized. Yet the stutterers in this novel are also born with unique abilities unknown to the society at large, special powers to transmit the voices of the dead. Your previous novel Half Life was about a pair of conjoined twins. Both novels in a way represent both the sort of “freak show” mentality of “norms” who are cruel to those that they other alongside empathic renderings of the experience of disability from the inside. Can you say a bit about why you are driven to telling stories centered on disability?

SJ: I grew up feeling like a freak myself. This was linked directly to my shyness, which was all concentrated on my mouth, on my disabling dread of speaking before strangers—though it’s not clear to me, looking back, whether I felt monstrous because I was so shy, or was shy because I thought I was monstrous. So of course I take the monster’s side. But the monster is not always a victim (let alone an innocent one). What makes her monstrous might also be exactly what makes her strong. In my case, it was my fear of speaking that made me a writer. So my real focus is not disability but alternative ability: the insights available to—and through—those whose experience of the world is radically different from the norm. I also think that what we call disability actually always reveals the truth that is hidden in plain sight in the normative body: the iffy and equivocal nature of the self.

Q: It’s also the case that the character of the stenographer Jane Grandison, who is both transmitting Sibyl Joines’s story and communicating her own, is a young Black woman, subject to bias both on the basis of her race and stuttering. Yet at the same time, because of her superior abilities as a medium, she is also the heir apparent to the headmistress of the school. The burdens of racism, it seems, have no influence on the relation of the living to the dead. Do you have any comment on how thinking about race and racism take form in the novel?

SJ: I’m interested in the way that, historically, spirit mediumship gave voices and an audience to people, mainly women, who would not have had them otherwise, and the paradox that their authority was derived from handing over agency to the dead—i.e, you can have a voice, but only if it’s someone else’s voice. It’s also interesting to me that that the voices they channeled often gave expression to marginal positions (abolitionism, free love) or were themselves marginal voices—the voices of so-called “Indian guides” or “Chinamen.” And yet of course these were often more like racist caricatures of otherness than truly other voices. So there’s a weird maelstrom of identity politics swirling around the mouths of historical mediums. In my version of spirit mediumship, the dead are denatured, stripped of the usual markers of identity, while the living are regarded as no more than vehicles for their voices. But while that means that a black woman can and does assume a position of power in the school, it is only by speaking for and as a white woman. I mean this to be troubling. The self may be an illusion, but if your claim to selfhood is under daily assault, you can’t lightly relinquish your claim to it.

Q: You chose to set this book in the early part of the 20th century, in a period roughly concurrent with the birth of the modern, and many of the letters are written to 19th century literary figures, such as Melville, Dickinson, Brontë, Poe, Stoker and of course Mary Shelley, as well as some of the characters from their work. Why was this particular period of transition attractive to you as a writer? Are these 19th century writers touchstones to you in a particular way, even as you wrote a novel that formally has a great deal in common with late 20th century literary postmodernism?

SJ:“The birth of the modern” suggests that the modern is a life form, and (in my necrocosmos) every life form is haunted by the dead that came before it. The rise of spiritualism in America was both about being haunted and was itself haunted. Here was this whole thesis about the capacity of ghosts to speak through a medium—a human being, a slate or OUIJA board, a piece of paper or, most notably, one of many recording devices designed for that purpose. And it seemed to me that this thesis was itself a ghost of past beliefs haunting an age of science, a way of channeling old ideas about the immortality of the soul through modern technology. There’s an amazing true story about a spiritualist named John Murray Speare, who built a machine (under instruction from a group of helpful spirits known as the “Associated Electrizers”) that was intended to house the second coming. It was called the “New Motor” or the “Wonderful Infant.” A woman calling herself the “second Mary” lay near the device and simulated labor, summoning the spirit down into the machine, which moved, a little. (A mob smashed it.) This seems to me not just an eerie real-life update of Frankenstein, but a perfect parable for the times, and brings me back to literature. I think postmodernism is a Wonderful Infant. The awareness, sharpening through the latter half of the 20th century, that language is a sort of fancy machine, operating on recombinant principles from the level of letters and phonemes through grammar and rhetoric right up to literary form, led to wonderful constructions. But something breathes through the machine, and for me it’s the 19th century. The writers I love were troubled and seduced by the spirit hid in the flesh, the flesh cladding the spirit. So I think I’m something like that absurd second Mary, calling down the spirit into the machine. Though really it was there all along.

Q: You’re a writer who has done a lot of work with metafiction—writing that is both about conveying a particular story and representing particular characters, but this is also simultaneously about the nature of fiction and storytelling itself. Metafiction is very clearly an element of this book, in the sense that words are transmitted from the dead to the living in the mouths of these children and retransmitted through them and through decoding technologies. So, while the writer is dead, the voice of the writer can in some sense be immortal or can at least live a different kind of life cycle than that of the flesh. In some cases, in the book, the word can even be said to be made flesh, or at least strange biological object. Could you reflect on some of the metafictional themes of the book? And is my reading here accurate? Do you think that in some sense fiction represents a sort of immortality?

SJ: I wouldn’t call it immortality. Literature is not alive, it’s undead. Language itself is undead, by which I mean that it’s the presence in us of the whole history of human speech, and effortlessly carries the countless voices of our dead. Every one of us is a spirit medium. The only thing that might make the writer special is a sharper awareness, both that we are in constant conversation with the ghosts of writers past, and that in our words we are already ghosts ourselves, haunting screens, pages, books (not to mention skin and snow) that we send out into the world to make their way without us. So yes, my book is about the spookiness of language, but the spookiness of language is also the spookiness of the self: like books, we are material bodies haunted by spirits. So metafiction, for me, is just a way of thinking about being human.

Q: My guess is that in publishing this book, you are yourself closing a significant chapter in your own life, in which this work has been a kind of continuous presence. But knowing you, there are probably a few other projects bubbling on the back burner. Any hints as to what you’ll pursue next (beyond writing in the snows of Brooklyn)?

SJ: I’m working right now on a collection of short collage pieces in which I take the front page of a given issue of a newspaper, usually the New York Times, and use it as my vocabulary bank: only the words that appear somewhere on that page or its reverse can be used in the piece. I guess it’s another way of rewriting the world, while also letting the world rewrite me. I’m also planning a couple of site-specific stories set in Brooklyn. And some sort of weird memoir, and…

Q: Thanks very much for taking the time to respond to these questions, and best wishes on the success of this remarkable novel.

SJ: Thank you for the thoughtful questions!

Cite this article

Rettberg, Scott and Shelley Jackson. "Room for So Much World: A Conversation with Shelley Jackson" Electronic Book Review, 6 January 2019, https://electronicbookreview.com/publications/room-for-so-much-world-a-conversation-with-shelley-jackson/