Text, Textile, Exile: Meditations on Poetics, Metaphor, Net-work

"Man Ray, Mina Loy, Gertrude Stein, themes of disorientation, displacement, diaspora, defamiliarized language" and that's just the d's. With such "little clues, like stitches coding a special language," Maria Damen weaves an essay-narrative based on her Summer 2007 residency in Riga, Latvia.

“Man Ray, Mina Loy, Gertrude Stein, themes of disorientation, displacement, diaspora, defamiliarized language” and that’s just the d’s. With such “little clues, like stitches coding a special language,” Maria Damen weaves an essay-narrative based on her Summer 2007 residency in Riga, Latvia.

In August 2008, I spent a month in Riga, Latvia as a resident scholar for the Electronic Text and Textile Project, under the auspices of the Electronic Book Review, in order to work on a book project that would bring together my thinking about two activities - writing and textile production on a hobbyist level - that have sustained me for decades. A departure from my usual practice of poetry scholarship in which I try to write poetically, this would be a poetics project, in which praxis and theory intertwine, juxtaposing reproductions of my hobbyist handwork page by page with exploratory short meditations. The residency culminated in a presentation to the “et + t” community in Riga, comprised in this iteration of poets, students of textile design and fashion, artists, cultural workers and literary/art critics and scholars. One of the original provocations for the larger book project has been the limitations of textile metaphors as they are used by textual scholars, and especially, in my case, my slight irritation with my friends in feminist literary scholarship’s somewhat facile and triumphalist appropriation of textile metaphors in the 1980s, as a kind of association of textual interpretation with the traditional “women’s work” of textile production - without really understanding the technology or the process of textile production, especially weaving. Without wanting to claim the place of the authentic Other, the handworker oppressed by the intellectual worker, I thought it was important to get the terms of the metaphor right.

However, as I embarked upon the work itself, the originary impulse to critique and to take the language of feminist literary scholarship to task has seemed less compelling; why not try a mode other than the reactive? And thus the project has turned from a critical one to a more engaged blend of production and reflection, in which I try to meld an active poetics with the textile practices of weaving and cross-stitching.

I. TEXT

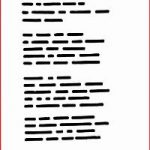

*[Man Ray illustration].

This is a poem without words, “written” by expatriate US artist Man Ray in the first half of the twentieth century. It makes a point about form, communicating in spite of its lack of words. It looks and feels like a poem - that is, what we think of as a poem - words, or word-like units, with their haloes of white space and their clear placement in lines: they are syntactic units without, in this case, semantic content. We don’t need semantic content to know that this is a poem. One can think of this either as a composition of blocks of ink that look like words arranged into a poem, in which case it could be considered an homage to the power of visual suggestion, or as a conventional poem in which the individuality and hence the semantic meaning of the words has been erased, leaving only the marks of erasure, which are much heavier and dramatic than the actual words would have been - in which case it could be read as a deconstruction of “poetry” as conventionally understood - and simultaneously an ideal poem (its immanent particularities having disappeared into a formal totality). We can even tell, to some extent, which words are probably nouns, which are connectives, minor verbs and/or conjunctions or prepositions, and so forth. “To My Sweetie,” could be the title, for example, or “Ode to Sunlight.” Etc. We can speculate on what isn’t there, or what is only there under complete erasure.

However, we can also call this a textile or fabric (etymologically, like the word poem itself, from a root meaning simply “to make;” T. S. Eliot dubbed Ezra Pound il miglior fabbro after the latter’s unmaking - the severe editing that led to its hailing as formally innovative - of The Waste Land) - material - a cloth with texture, pattern, and tactile as well as visual appeal. We want to touch those thick noodles of pseudo-words the way we want to touch a thickly textured tapestry, rug or even scarf. The word “impasto” and its resonance with “pasta” makes us wonder if, Kant’s exhortations notwithstanding, artistic consumption can be disinterested - if the hunger it arouses and feeds is ever free from corporeality. The poem’s black and white format suggests Navajo or Danish modern rugs, elemental and foregrounding pattern through color contrast, harsh and sturdy, built to last, and with metaphysical codes embedded in the weave itself.

*[Navajo Rug Illustration]

And most significantly we can even “read” this text as a textile through feeling it rather than through semantically cognizing it. Even if we don’t literally touch it - and the digitality of this presentation assures us of that, since to touch a computer screen is to risk destroying it - , we can feel it in our minds. That is, we can read writing that is not comprehensible to us as communication in the conventional sense. This is one kind of text that can also be construed as a textile - also derived from “tec” - to make - through texere, to weave (a root which also gives us, obviously, techne and technology). Transporting the reading of the poem beyond the semantic level one usually associates with verbal texts opens up a wide-ranging network of associations among the cognates text, textile, texture; the poem/textile takes on different kinds of textuality in its wandering across media and art forms. While Man Ray (né Emmanuel Radnitzky, in 1890, Philadelphia, possibly part of Gertrude Stein’s families extended network of co-religionist immigrants), whose truncated name underscores his highly gendered performance in modernist circles during his life, was hardly a textile artist, the term certainly applies to his lover Mina Loy, a British-Jewish poet, feminist, clothing designer and fiber artist whose status as a multi-artist complements her self-described “mongrel” ethnic status. (And here the theme of “Exile” should start to play very softly in the background of your reading experience, but please, not the theme from Exodus… )

If we were together, dear readers, as we were in the et + t’s large living room when I gave the final presentation of my residency, we could possibly read Man Ray’s text aloud. I won’t (,can’t, and didn’t) insist that we do so, but I do want you to give a moment’s thought to how such a performative reading might be done. To better understand this possibility I invoke the spirit of the late British avant-gardist, Bob Cobbing (1920-2002), who used to heavily mark letter-sized paper with magic-marker so that the ink bled through to the other side in suggestive but non-recognizable inscriptions; he then would photocopy these reverse-side markings and bring them to workers’ adult education centers where, with large projections of the texts on a screen at the front of the hall, he would conduct choral orchestras of the workers singing them aloud in whatever unison they could. Far from being coercive exercises in acculturation to a world of high Poesie and Music, these were hugely enjoyable comradely “happenings” that were not judged by the standards of a disciplinary class society in which access to the arts is a form of uplift. So there exists the possibility, in a crossing over of class consciousness and artistically vanguard practice, that these experiments in textuality and orality, cross-sensory translations, really foreground what reading is in both senses: interpretation (of a face, a poem, a palm, a “situation”) as well as performative rendering, since to perform, one needs to construct and render a set of understandings of what the text is. And more: the possibility that some kind of non-alienated experience of work, aesthetic pleasure, and sociability can arise from this blending of text and textile practice - mine and many others, as well as the Cobbing events.

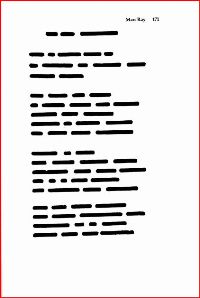

[For Bob Cobbing in the Snow, by David-Baptiste Chirot. illustration]

Another visual poet, David-Baptiste Chirot, who leads a tenuous existence in Milwaukee Wisconsin, avails himself of street debris and found materials to echo Cobbing’s intent and aesthetic in a serial homage to the British poet; one of this series covers paper with a distressed patina of letters and numbers (dripping? melting? burning? half-rubbed-out, like marginal human beings?) that, toward the lower left, include the word FOUND, the words “replicated” and “badly” hovering near each other, and the phrase “damaged by fire” a photograph of a man (not Bob Cobbing) in winter clothing, hands in pockets, looking downward as if drawn into himself against the social and thermal elements, handsome in a bohemian/ruffian/artist way; as well as rubbings and dramatic creasings in the paper contribute a “background” of semi-decipherable text and markings. Chirot, who often uses rubbing and collage techniques to establish communion with the “RubBeings” he discerns in inanimate objects such as telephone poles and manhole covers, also brings together a thickly textured materiality that is both textual and trans-textual, textured and textilic in its evocations. Such a trans-continental call-and-response is itself a weaving, knitting, lacing, or - pick your gendered handwork metaphor! - that disseminates new artforms and net-works artists on the edge.

II. TEXTILE:

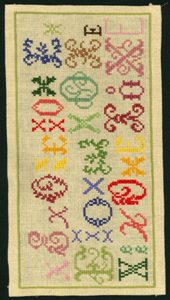

Just as, in the examples I’ve offered here, Man Ray, Bob Cobbing and David-Baptiste Chirot blur the boundaries between visual and literary art, and also between participation in the world of poetry making and commentary on it, my recent literary practice incorporates textile poems as meta-commentary on poetry and poetics, but through a gift-economy that circulates through my network of poetry friends and colleagues, in a reverse trajectory from Man Ray’s in two different senses and through two different textile practices: in cross-stitched visual poems, I create semantically meaningful words in cloth, while simultaneously defamiliarizing them by heightening the formal aspects of the letters themselves; and in weaving, I create long, rectangular shapes (shawls, basically, but we can think of them as giant scrolls) that establish and at the same time try to estrange the familiarity of traditional patterns, in this case Appalachian, thus creating and at the same time distorting narrative and communication, blurring not only the boundaries between visual and literary art, between participation and commentary, but also between “signal” and “noise.” In the music world as in the textual world, textile metaphors abound: Keith Richards has referred to his work with the other Rolling Stones guitarists as practicing “the ancient art of weaving,” marking the Stones as essentially a British band, and essentially domestic, rooted in the artisanal household, despite their desired association with African American culture through their early choice of covers, their investment in the blues as inspiration, and their name, which include rootlessness, transience, constant diasporic mobility, and anonymity (and Richards, despite his clearly sincere admiration for the blues and related forms of music, has been firm in wanting to preserve the Stones as a British band). Although weaving and cross-stitching are different forms of textile production - one creates cloth from yarn or thread, the other embellishes existing cloth through iterative piercing and stabbing, a form of ornamentation which is also violation - both rely on a grid, on a binarized, Cartesian graph form that underlies much Western thinking. So while one can make some appeal to the status of textile work as traditionally women’s work, subordinated to and thus somehow resistant to the master narrative of high art and philosophy, there’s more to the story; the small terrain of women’s handwork in some instances echoes the plotting of gardens, the territory of conquest, the plaid of sectarian “colors” and nationalist flags.

I spent my residency in Riga cross-stitching, so the following focuses on that needle art, though the larger project involves weaving, and I was able to acquire some wonderful Uzbekistanian wool from Astrida Berzina, a textile artist who is downsizing her yarn inventory.

The cross-stitches I execute now are tokens that I send to friends and colleagues. But my interest in the literary possibilities of handwork started years ago when, in my early twenties, I wanted to x-stitch on a white skirt my favorite literary quotes, in heavily ornate French lettering from an alphabet pattern I liberated, along with a microscopic crochet hook whose use I’ve never mastered, from the apartment of a French royalist; an apartment I rented with some other girls in Paris when I was eighteen; an apartment filled with old flags and hugely dramatic crucifixes. However, the work on this white-skirt project was so labor intensive that in four years I only managed to execute two inspirational sentences: one from a Bernard Frechtman translation of Jean Genet, “We cannot suppose a creation which does not spring from love,” and the other from Gertrude Stein’s Lifting Belly, “In the midst of writing there is merriment.”

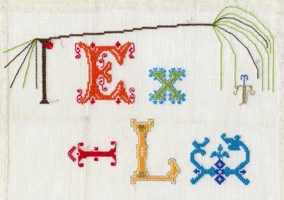

Many years later, in 2000, after I had completed graduate school and twelve years of university teaching, a poem by the poet Lee Ann Brown inspired me to embroider on a small square of linen a line from Lee Ann’s poem as well as the words “Tender Buttons” - the name of her press dedicated to publishing the work of experimental women writers, and named, of course, after Gertrude Stein’s masterpiece; I mailed it to her PO Box in Manhattan, on pins and needles as I waited for her response. Strangely, she responded as soon as she received it, but I didn’t get her email for a month or two. At the time it didn’t cross my mind to document the piece - it was not yet a “project” - so I have no recollection of the words I actually stitched, beyond “tender buttons.” As I had no consciousness that this would become a practice that required documentation, there is none. But the practice evolved of making elaborate words, or configurations of letters saturated with interpersonal meaning and giving them to friends. For instance, after several years of fulfilling collaboration with the poet and publisher mIEKAL aND, I made a field of X’s, E’s and O’s to reference his press, Xexoxial Editions, and also to underscore the epistolary nature of our collaborations with the salutation XO, as I often sign my postings (“xo, md”) to the various poetics and writing listservs I belong to.

[Illustration X(exoxial)-stitch.]

Most often I conduct the actual cross-stitching at conferences or poetry readings, or department meetings; places where my professional, creative and intellectual energies were stimulated and/or sublimated.

[Illustration: Aldon Nielsen photo of my x-stitching at a mass poetry reading at the Philadelphia Modern Language Association off-site poetry reading, December 2006]

It is not unusual these days to see women knitting at such meetings, so this is not an outré practice, or even a particularly quaint one. What is perhaps less common is my need to integrate textile handwork into my intellectual and creative life both thematically and as a meta-method; it’s not (only) an escape but an alternate mode of processing and participating in the exchange of energy that happens at these meetings. mIEKAL aND, a longtime DIY cultural anarchist, encouraged me to think of these as visual poems; they are sharply inspired by moments in which intellectual and social pleasures coincide. Mostly, the pieces are invented as they are created, and they have been sent to their respective dedicatees to complete the cycle of social and intellectual/creative networking. ;They are about friendship in cultural work.

Goethe wrote - and this is certainly counter-intuitive in a contemporary poetry landscape, in which the perfect lyric is considered to be suspended in time/space, transcending whatever moment occasioned it - that the highest form of poetry is occasional poetry, that is, work produced to mark a particular occasion, whether historical (an election), or personal (the wedding of friends, the event of a great concert), or even more privately, an expression of friendship triggered by a remark, an evening of warm conversation, or a moment of sharp intellectual engagement. Such work is de facto embedded in an immediate and often intimate social and affective context. Becoming increasingly local in one’s intended audience is not therefore a retreat from the responsibilities of public artmaking or critique, but rather an enhancement and specification thereof. From understanding this practice as simply a hobby, I’ve come to see it also as a participation in networking and poetics, sharing with Gertrude Stein, Ezra Pound and many anonymous but dedicated others the belief that connecting people to each other through project-based work and through artistic friendship is a highly legitimate literary practice.

My tools are all beautiful objects on their own terms: pattern books of alphabets, monograms, designs and borders; blunt needles and coarsely woven white linen; a massive tangle of Danish Handcraft Guild flower thread in almost every color they offer, as well as a bit of metallic thread in silver, gold and red. It is something of a conflict to press these tools, especially the yarn, into service of a specific project, as the promise of potential in the snaky tangled skeins is powerfully evocative. The cloth too, purchased in large quantities from which I cut smaller squares, literally suffers diminution and dissymmetry when I appropriate those subdivisions for transformation into an inscribed surface, however colorful and semantically rich. The degradation from an idealized blank screen/page to the fulfilled execution of a necessarily limited vision can only be redeemed by the gesture of transmission: the physical giving (or, most often, mailing) of the piece to its intended interlocutor, whose reception lifts the piece out of aesthetic self-containment and inserts it into an affective context.

Here are the pieces I’ve executed while I’ve been here.

Open Up and Bleed: For James Osterberg, Jr.

This piece is flamboyant and colorful, with silver accents to reference Iggy Pop (James Osterberg, Jr.), the Godfather of Punk and the silver lamé gloves he used to wear in early performances; red metallic stitching from the central letter (O for TV Eye and for “O Mind,” Stooges argot for being in the right orgiastic and meditative state of mind to receive music) to indicate the blood shed in the name of art, as Iggy was prone to either slash his chest with broken glass or beat his chest with the microphone so hard he bled, or scratch himself ritualistically, etc. He speaks of being transported beyond himself by the power of amplified sound, and these self-mutilations in a trance state are echoed in the gestures of piercing and stabbing that comprise needlework. He was also, famously, an intravenous user of heroin, to such a degree that his career was severely compromised more than once. As Iggy uses his body as a material signifier and as a canvas on which he marks his emotions, even though I’m using the very rigid form of the grid, the needle and the counted pattern, I try to use the vibrancy and dynamism of letters to convey motion and emotion (his heavily libidinized spirituality; in interviews he’s explicitly aligned himself with Dionysian performance rather than Apollonian art objects), the interplay of chaos and meaning through artistry. And I’ve left the blunt needle with a bit of red thread in to suggest that the choices he makes about how he lives his life are artistic decisions that he can make; he is not at the mercy of his weaknesses and addictions but has the power to turn them into art. I debated removing the needle when I actually send it to him, because it might look too much like a provocation; but ultimately decided to leave it there, as it also indicates the never-entirely-finished project that is a life and an artistic practice.

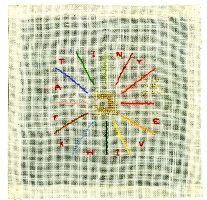

Terra Divisa/Terra Divina: Divided Land, Sacred Land (T/E/A/R)

In June 2007, the Space and Place Research Collective I participate in at the University of Minnesota teamed up with a British collective, Land2 (pronounced “Land-Squared”), a group of artists who are also actively theorizing their work in the problematics of space, place, and history. Among them is Iain Biggs, a university administrator trained as a visual artist, whose self-published books meditate on conflicted sites of British memory, folk music, artistic renditions of the inner cost of border conflicts, and his own subjectivity vis à vis these matters. He sent his latest book, Vol. 1: In Debatable Lands, to 200 people asking for a response within the year. Debatable Lands is the contested border area between England and Scotland that was characterized in the 16th and 17th centuries by government-sanctioned lawlessness and murder. Here is my response.

TERRA DIVISA/TERRA DIVINA: divided earth, sacred earth.

The word TEAR is a double meaning, tear as a verb, to rend or separate violently and jaggedly, and the tear one cries in grief or pain. The letters T-E-A-R also resonate with the words EARTH, HEART, ART, TERROR.

From the letter I sent to Iain about the piece:

T/E/A/R is bisected by conflict on the diagonal. Brown and green for the earth itself and its cycles of rest and renewal or, more violently, death and rebirth.

…

I used lettering from Scots and English childrens’ samplers. That these are made by children and now collected by adults adds to the conflictual status of “outsider” or “naïve” art.

The large, ornate T and A are from a Scottish 1750s sampler, described in my pattern booklet as “a step toward the majestic illuminations to follow.” The A takes pride of place and space; it’s the largest letter, spilling over its borders. It resonates with the US classic The Scarlet Letter, Nathaniel Hawthorne’s 19th-century novel about a woman who dares to live outside society’s rules in the most basically gendered of ways: having a child “out-of-wedlock.” As penance she is forced to embroider an A (for Adultery) on her clothing, while the child’s father, a young church minister, goes unknown and unpunished. As an assertion of her Artistry and humanity, she makes the A as ornate and elaborate and gorgeous - a “majestic illumination” for sure - as she can. The story of Màiri nighean Alisdair Ruaidh [a fierce semi-outlaw woman singer who asked to be buried face down to “stop her mouth with dirt for eternity”] reminds me that A is, of course, also the Artist, so Nathaniel Hawthorne, descendant of the Judge Hathorne who condemned the Salem witches, carries a closet identification with his heroine despite his complaints about the “damned mob of women scribblers” whose popular fiction compromised his craft. Màiri’s stated desire to be buried face down so that her expressive arts would be forever and redundantly condemned to silence (death itself is not enough; the punishment, as Foucault and Hawthorne remind us, must be spectacular, even if, as in this case, no one can actually see it, as it is underground) prompted me to turn the A upside down.

The smaller E and R are from an 1840s English sampler made in an orphanage. I thought I should include an English “font,” as representative of the other side of the border dispute. Although my booklet includes patterns based on English samplers from 1590, a more appropriate date for the Debatable Lands material, the letters of these older samplers were a bit too stark and small-scale for the project, which relies to some degree on the deterritorializing effect of embellishment; moreover, the pathos of English orphans being taught to do this dying art (by 1840 the advent of industrial textile manufacture, even the embellishment of embroidery and cross-stitch, meant that this form of production could only be a disciplinary measure rather than a useful pedagogical transmission of practical skills) indicated this 1840s pattern as the right choice. Children who have been torn from their families and/or their social place and institutionalized suffer a diasporic border-war of their own, internal as it may be. The original sampler lettering did not include the outlining of the letters; I added that to amplify the letters, making them appropriate for the balance of the piece.

As an added bonus, I noticed, as I near the end of the project that the pattern booklet I’ve used (Marsha Van Valin, Alphabets from Early Samplers: Sixty-four Examples from Samplers Dating from Circa 1590 to 1868, With Charts and Authentic Color Schemes (Sullivan, WI: Scarlet Letter, 1994) is published by The Scarlet Letter, clearly a highly niche-specific and likely humble publishing company in rural Wisconsin - maybe even a one-woman operation?

III. EXILE.

Feeling estranged and disconnected in a new country whose language is unknown to me, I took Iain Biggs’s cue and wrote to the friends and colleagues I’ve made things for over the years and asked for some kind of response. Some sent pictures, some poems, some mini-essays. One even sent a power-point presentation. This enactment of net-working across diasporic distance was a way to generate creative energy, which I find is most stimulated through conversation and interaction; hence the need for collaboration in the last decade or so.

I asked specifically that they comment, if they could, on the “textuality” of the pieces: that is, how they could be “read.” But I also stipulated that any kind of response - a photograph or a drawing - would be acceptable. I got wonderfully varied answers from a range of poets, friends, and colleagues. Ed Cohen, who teaches cultural studies at Rutgers University, wrote a short essay entitled “Tensions and Tendencies,” drawing on the Bergsonian notion of the durée, an unspecified stretch of time, and dwelling on the “potent absence” he intuits in the warped loom that hasn’t yet been filled with weft. Internet historian Christopher Funkhouser, to whose family I’ve given various handworks (a wedding shawl, a table runner and a baby blanket), hypothesizes correctly that

editorial decisions are made in the moment, and … this as a type of making that derives from what is present, or what presents itself … the overall design, after its structure had been established, may have discovered itself as it went along… , the silver thread (lining) is the unifying, steady element. … It goes without saying there’s a back and forth to all of the pieces… (Funkhouser)

The term “back-and-forth,” used as a noun in English, is like the noun “give-and-take;” it indicates a satisfying, mutual exchange of ideas characterized by openness and engagement. Funkhouser himself performs this generosity of spirit by responding to my query, as did all participants.

[Illustration: B: Tiny Arkhive, for Adeena Karasick]

In response to this illuminated letter BET, or b, of the Hebrew alphabet, a tiny ark-hive, Jewish-Canadian performance poet and feminist Kaballah scholar Adeena Karasick writes:

Tiny Arkhive, housing Bet [בּ], the second letter of the Hebrew alphabet (closed on all sides and open in the front, with a dagesh-dot living inside), you stand in for the House (Bayit) of the Wor(l)d. i inhabit you. Live now inside these three walls and an opening, en passage, of exits and entrances, vacancies, tremors.

This tiny arkhive, wreaking havoc, hovers housing the world, its origin, which has no origin, which is always already throbbing with frenetic extension: expanding and contracting and swirling in archival upheaval. Housing the sacred ark (writings) resplendent with écriture this creature of craters sutures saturated in intertextilic excess.

Little arkhive cross-stitched and emanating, i read you as an embroidered network of socio-linguistic and hermeneutic relations.

According to the Book of Letters, “You can walk into a Bet [בּ], and you are at home.” “Because there is no longer a home [chez-soi] and a not-home [chez autre]”, but housed in homily, unheimliche, unhomely, homeosis, a homeopathological lacuna, everything is [IN THE HOUSE]. You are an “Open House”, which is at once in place, while deprived of any one place. In its place and in place of; re-placed in hyperspatial interplays, you, my tiny arkive, displaced en plaisir.

Tiny Arkhive, you are the second letter, whose numerical value is two. And, as such signify a doubling, diversity, heterogeneity, multiplicity. But as it is you who are the first inscription in Breishit [בּ], (the blueprint of the universe), you remind us that the first is always a second, a doubling. Everything always already begins not “In the Beginning” but “With the beginning”, as i take you with me through all the syntagma magma, rippled tropes, topos; through ellipsis, scission, decision, excision. You, tiny arkhive, represent how origin must be understood as not a fixed point, but travels through time, history, language and context.

And according to the Sefer Yetzirah, each letter actually contains every other

“Bet [בּ] with them all, and all of them with Bet[בּ]”.

So you, Bet [בּ], are an intra-linguistic accumulation, a radiating energy source of fiery potential that contains the possibility of all things.

Hewed and engraved, you are always already there. I feel you breathing with me as a resonant present you are with me in the beginning, at the beginning, through a beginning or with the beginning. With you, everything has always already begun.

As an inscription of textasis, an intertextile, text in exile

stitched and restitched as an interwoven matrix of desire, you curl into yourself, highlighting the (in)finite spiralling nature of language. Calling and recalling caressing all the letters, all the inscriptions, all the beginnings, labyrinths emanating from you. (Karasick)

Masha Zavialova, a Russian literary translator and curator, used different fonts and typesizes to disorient and interrupt her own text in the way she felt I disoriented and interrupted patterns and expectations in the rough blue, brown and purple and off-white shawl I made her to recognize her volunteer work for the website VG: Voices from the Gaps, a data base for information on women artists and writers of color housed in my department at the University of Minnesota. She made the point that the variety of colors reflected the “left-overs” of materials from other projects “or else made from… old knitted things that she turned back into yarn and re-used (a usual procedure for my Russian female relatives… )” She refers to me as the “author” of this text, whose colors she characterizes as “pure colors rather than context-bound excerpts from past LIFE.” She writes:

Sometimes I look at its various patterns that never repeat themselves, and see it as a chain of words in a sentence or a kind of speech that has its unique start in the here and now that is gone, inviting a reply that will mark its end and will be a completely different here and now that has not started yet. The shawl unfolds its patterns as I do my casual conversation: I say something that can never ever be repeated in exactly the same way and the words I say cause other words to appear and connect with the previous ones into a pattern that will be impossible to break. This pattern is sealed by Time.

But then again, I turn the shawl upside down and now its beginning is its end and vice versa. (Zavialova)

[Illustration: Spore-Form]

My poet friends, Barrett Watten and Carla Harryman, responded to Spore-Form, a piece I made while attending a conference on Diasporic Avant-Gardes that Barrett had co-organized in 2004, with poems very different from each other. Watten, a highly theoretical Marxist poet associated with the so-called Language Poets from the 1970s onward, wrote this, after reading that there’s always a “spore of doubt” associated with the Grassy Knoll, the area from which it is speculated that President John F. Kennedy was really assassinated (and thus forever embedded in highly plausible conspiracy theories):

Spore Form

for Maria Damon

Spa fon. The postmodern condition as typography.

Spare parts. There would always be a spore on the

grassy knoll. We awake at the same moment to our-

selves and to things. SPF 15/30/45. The constant noise

of truck traffic as the sensible form of our unknowing.

Do not think of anthrax for one minute. Head comix

pile up in the attic, the basement, the water closet.

She knits and purls as if revolution were taking place.

Each element speaks to a fading ensemble directly.

It is material, she screams, material, materialism!

And Carla Harryman described the piece in much more sensuous terms:

Spore Form for Maria

Of of the elaborate form

an F nestled in

O’s Spore

R is going somewhere

running for Rome

or from home

Rome’s spore

of stitches

thick swills

on small mat

the rim of a globe

and a big M

Strong element

under revolutionary fly

in coil scaled to eye

Man Ray, Mina Loy, Gertrude Stein, themes of disorientation, displacement, diaspora, defamiliarized language: these little clues should indicate, like stitches coding a special language, or breadcrumbs showing the way through the forest, that we will eventually come to EXILE, the third element of my talk that is in some ways most difficult to integrate with the other two, Text and Textile, although there are rich traditions in Jewish culture in both areas; as you probably know, Jews are the original People of the Book (and I hope you can discern the influence of Jacques Derrida in some of the foregoing emphasis on writing’s many forms), so it should be no surprise that textuality is a favorite metaphor, no, more than a metaphor, a ground of being. I didn’t realize I was coming to the home of Isaiah Berlin, Mikhail Eisenstein, and others when I came to Riga, though I knew it was not far from Vilna (City of Wool?), the metropolis closest to whence my paternal grandparents and great-grandparents emigrated during the pogroms of the 1880s.

Anda Klavina arranged for me to have a walking tour of the 1941 Jewish ghetto area here in Riga with Ilmars Zvirgzds, who has an intimate knowledge of the area and has published text and photographs of it. Ilmars explained to me that though there were virtually no more Latvian Jews in Latvia, the area is still a ghetto, of the poor, of gypsies, of down-and-out young Russian men. He interpreted the political graffiti by leftists and their white supremacist enemies. As I walked the streets and imagined what it must have been like, overcrowded with doctors, professors, merchants, fish salesmen, tailors, rag peddlers, children, grocers, on their way to death, the present seemed much more accessible to me. It was a beautiful morning, sunny and warm, but the wide cobble-stoned streets seemed pained with absence and history. We turned down some smaller side-roads where people had created shelters and gardens for themselves out of very few resources. U nderfed dogs stood tense watch amid the tangles of trees, vines, wire fencing, wooden sheds, flowers and clotheslines. Then we came across this beautiful sight, a shed door with Russian graffiti:

[Illustration *Slezhubni: Service Staff Only]

Instinctively I asked Ilmars what it meant. After a pause he said, “It’s layered with so many meanings I can only begin to unpack them for you.” Another pause. This was gonna be good. ” The closest I can do is, you know, in an airport you might see this sign, ‘Staff Only.’ Here it can mean anything.”

It was a piece of sheer outsider exuberance. Whatever goes on in this shed, drugs, prostitution, or simply someone saying, “Keep out because this is all I have, and it’s mine not yours,” and simultaneously, “Come on in if you’re one of us, you’re welcome here,” epitomizes Walter Benjamin’s characterization of the exiles, history’s non-triumphant survivors: their cultural practices, their very conversation and gestural style, are marked by “Courage, humor, cunning, and fortitude.” This word, slezhubni, patterned on the rough page of the wooden shed-door, is the perfect micro-poem and doesn’t need to be embroidered on white linen; though perhaps it will be.

The code that protects, includes, excludes and resonates with loss and survival historical, present and potential, gives us a means to backtrack to Man Ray’s poem in the context of text, textile, exile. Its thick, obscurantist and hyper-tactile lines can be understood to prospectively thematize the suppression of language, of culture and people and foretell their potential obliteration; and simultaneously it enacts a coding that enables the invention of a gestural language without national boundaries, based on a need for art and expressive culture. If we were to voice it then, it might be in all languages and none, all sound smooth and striated, meaningful and chaotic, Dionysian and Apollonian, the birth of creation in a textual tapestry. As Funkhouser remarks in his response to the gifts of ordinary domestic objects - baby blanket, table runner, wedding present/lap-rug - : “Oblique stories are told… practicing such experimental design is life itself.”

CODA:

In each of the three preceding parts: Text, Textile, and Exile, the concept of texture has emerged as central, so I close with praise of the local, the micro and the tactile in the form of a brief meditation on the word itself, a lettrist transposition inspired by the et + t’s call for papers on the subject:

Texture Vs. Ur-text

A. Ur-text is above and below, a paradigm and a paragon. It is a top-down breath-taker, jaw-dropper, nice and proper, overwhelming in its ideality, not a hair out of place, every anomaly erased.

Text-ure is down and dirty, grit and nubby, the streets and walls, rough façades and bumpy, moss-encrusted rust patches on Riga’s old buildings, down toward the sidewalks at the lower end of the edifice, far from the friezes and ornamentals, which may themselves turn out to be rusty and dilapidated if you cd get close to ‘em. Texture gets your hands dirty and dig your fingers in. Nap and patina, oxidized powders, copper excrescence (green from copper, rust from iron), velvet from satin, slubs from skeins, shine from silk, roughed-up from abraded fingers leaving spiky threadlets standing up in delight.

I like textured writing; that is, ornate, self-conscious and self-aware, “poetic” writing that foregrounds its style. And yet is humble and almost furtive, out-of-the-way like Jean Genet, whispered from the cracks in prison walls and warming up the human misery inside, reveling in its eccentricity because that’s what it has going for it. Mannerist. Exaggerated. Henry Darger on a huge white charger coming to save us from ourselves.

B. Texture is that which resists: graininess, frictional pleasure, creating meaning in its micro-challenges (the whorls and eddies of the fingerprint). Texture as dirt, the hermeneutic anomaly, the raised weal of flogged skin, the damask rose on the featherbed cover. Texture is to touch as timbre is to sound: its connective and collective tissue-event, as it takes a haptic auditor, as it were, to appreciate it. (Keith Richards and Ron Woods refers to their work together as the Rolling Stones’ guitarists as “the ancient art of weaving.”)

Texture as the “between,” in Joe Tabbi’s formulation, is also a compellingly riffable trope. Riffraff on the riprap, hiphop on the fly. It’s in the layering, the sampling, the folding, the labializing and origamizing of the surface.

Crocheting a coral reef as a collective project (<www.theiff.org/reef/index.html>), semi-anonymous, detonates the concept of multiplicity as intrinsic to “texture.”

But smoothness is also a texture: glat kosher (the lungs of the slaughtered animal are smooth, i.e. glat, i.e. not diseased), more kosher than kosher, a bit better than good. Highly disciplined, highly disciplinary. Abraded texture is a roughed-up disciplinarity.

Can we think institutionally about texture as “scarified inter-disciplinarity” rather than the smooth interdisciplinarity of, say, historicism or the “art and literature of… ” model that predates it? An interdisciplinarity that weasels into the apertures and closures, making sure there are no untroubled spaces. In the between is where the ghostly fingers play against the curtains.

But can we think about smoothness without its being facile or glib? Why the need for complexity and difficulty, as if that were the only index of worth? Is there no such thing and “needless complication”? Of course there is, and so there must be some corollary “necessary simplicity” that is not a dumbing down. The smoothness of a stone worn by millennia of friction in the ocean… well there we have it; smoothness is earned by millennia of friction! Is there no other way? Smoothness is simple when a flower springs into being, or so it seems, though a microscope would reveal folds and fissures… Again, there is not one without the other, and they are neither opposed nor in a relation of non-opposition.

Cite this essay

Damon, Maria. "Text, Textile, Exile: Meditations on Poetics, Metaphor, Net-work" Electronic Book Review, 12 February 2009, https://electronicbookreview.com/publications/text-textile-exile-meditations-on-poetics-metaphor-net-work/