The End of Landscape: Holes by Graham Allen

In her discussion of the textual, technical, and figurative characteristics of Graham Allen’s Holes (2017), Karhio “argues that [Allen's text] is not a landscape poem in the customary sense” and explores the ways in which the digital platforms deployed in the project’s creation and publication contribute to the signifying structures that “challenge the idea of landscape as symbolic representation of the inner world of the speaking subject.”

I

The relationship between digital literary production and literary traditions in national contexts is complex and often characterized by varying degrees of dialogue, curiosity, and suspicion. As Maria Engberg and Jay David Bolter have noted, “because of the indifference or hostility of the literary community, the decision itself to produce a work for digital presentation becomes for some writers an act of opposition to the mainstream” (2). Opposition itself takes many forms, however, and often requires an engagement, if not an agreement, with established practices of cultural production. In poetry, the motif of landscape offers an example of how a literary (and visual or aural) aesthetic can be employed to interrogate more conventional forms of literary and cultural tradition, and expression. A considerable amount of scholarship exists on landscape as an aesthetic, cultural and phenomenal concept. In poetry in particular, place and landscape have been perceived through moments of epiphany and intimacy between the speaking subject and the phenomenal environment, or as embodiments of cultural and national narratives. In the Irish context, Gerry Smyth is merely stating the obvious when he notes that “if there is one cultural practice which over the years had laboured […] under the weight of a supposed ‘special relationship’ between place and Irish identity, it is poetry” (56). Against this backdrop, the following discussion will focus on Graham Allen’s long digital poem Holes, and on how, as a born-digital text, it comments on the leitmotif of landscape, and simultaneously refuses the aesthetic and discursive forms that have characterized poetic engagements with this motif. This end of landscape understood as aesthetic and cultural representation of the (visual) terrain is also “end” as purpose, a search for an alternative approach: new media platforms are engaged to reconfigure verbal art’s relationship to the perceptual environment.

In short, the following discussion argues that Holes is not a landscape poem in the customary sense. It does include images of landscape understood as “a section of the earth surface and sky that lies in our field of vision as seen in perspective from a particular point” (Hartshorne quoted in Olwig 630) or as a panoramic vista observed (and simultaneously created) from a distance,1 but such imagery never assumes the role of a governing framework. Instead, Holes as not-a-landscape-poem makes use of its chosen digital platform and aesthetic in a manner that challenges the idea of landscape as symbolic representation of the inner world of the speaking subject (“the lyric voice of a lone poet”, as Allen and O’Sullivan phrase it), or as embodied or shared cultural narrative. This is largely made possible by the use of a digital platform in publishing the poem: while Holes adopts formal and aesthetic strategies that also characterize much non-digital (or pre-digital) poetry, it reveals how these strategies can, retrospectively, often be seen to anticipate a distinctively digital literary aesthetic. More specifically, Holes enacts what Lev Manovich has termed as “database logic” or aesthetic, as Allen and O’Sullivan (2016) have already observed: it “rests on the electronic database” [a MySQL database and “a customized Wordpress frontend”] and “manifests at least some of that medium’s potentialities.” Inasmuch as the motif of landscape, in the Irish context in particular, has almost exclusively been understood as a visual metaphor of cultural and historical narratives, the aesthetics of the database can challenge narrative cohesion through alternative processes of accumulation and patterning; the database suggests “a different model of what the world is like” (Manovich 219). In replacing what Ervin Panofsky called the “symbolic form” of “linear perspective” (ibid.) - constitutive of landscape art in Western art - with the aesthetics of the database, Holes also points towards a method of re-configuring our relationship with the surrounding world that moves beyond worn-out discourses and metaphors of spatial representation.

II

Holes was inspired by its author’s engagement with Jacques Derrida’s landmark lecture “Structure, Sign and Play” and its rejection of the idea of center; the poem similarly discards an aesthetics of a “centred structure” (Allen and O’Sullivan). It consists of dated, strictly ten-syllable lines, one written for each day since December 23rd 2006, with no stated end-date. According to the website, it “represents a new approach to autobiographical writing” (Allen, *Holes;*all subsequent references to the poem are from the same source). The lines resemble microblog or Twitter posts, the online equivalents of diary entries. The homepage also directs the reader to close-up photographs of rock surfaces, walls, and similar materials, which accompany the poem but do not explicitly comment on it (or vice versa). Initially, Holes was composed off-line in a non-digital setting, and was only in 2012 moved to its current online location, where new entries have since been published once a week by the Cork, Ireland based digital publisher New Binary Press. The entries of the first year were also published as “365 Holes” in a 2009 special issue of Theory & Event, with all contributors commenting on, or reacting to, Derrida’s famous lecture. In his introduction to the poem, Allen contemplates on a poem that would take “Structure, Sign and Play” as a manifesto for poetry, one that “would have no quotable core” but would instead offer “a series of touchstones, soon to be tombstones. […] instead of a centre it would have a series of holes. To be filled, to be added to […] Little peepholes, like the stars are peepholes, onto a reality that is beyond structure” (“365 Holes”). Such poetry, Allen contends, “would never after need to end, until the end” (ibid.).

The poem’s governing metaphor, the title word “holes,” is constantly evoked in the text, in different contexts and in all senses of the term, literal and figurative, from the intentionally rude or gruesome to the metaphorical or self-referential. At times the word is used explicitly, at times through the inclusion of synonyms, or by implication: “2015-07-26 The only hole you need is in the head,” “2014-04-23 Vacuity, lacuna, puncture, scoop. / 2014-04-22 Perforation, foramen, fissure, cleft,” “2014-01-11 Standing outside of Eason’s writing Holes,” “2013-11-16 Shall I let you see through the hole today,” “2011-05-12 Each day of your life is a single frame.” Such lines are a constant reminder of the absent center that the image of the hole is said to stand for in Allen’s introduction to “365 Holes.” It is the center removed, or demarcated only by its edges. It only exists through its limiting border, like the “single frame” in the entry for May 5, 2011, and thus directs attention away from what lies outside, and towards its own missing materiality, as a “puncture”, or the aperture of the camera lens. The image also unavoidably evokes the idea of point of view as an opening through which we see, key to the emergence of perspectival view in visual depictions of landscape. Yet “the point of these holes,” Allen stresses, “is that they’re too small to see much through” (Galvin). They are too small but also too numerous to offer a coherent vista. Importantly, therefore, it is the repetition of the one-line entries as a series of holes that undermines the idea of point of observation as structural center.

Repetition through time is thus crucial to the poem’s aesthetic and philosophical underpinnings, and also to how it depends on its online platform as a means of dissemination. Only as a pliable, digital work can it “grow textually and visually to the public eye” (Allen and O’Sullivan). And as Allen and O’Sullivan remind us, “Holes was not born digital”, but was “reconceived [by] placing the poem on a digital platform”; in this sense, “Holes is, and is not, born digital.” It is beyond the topic and scope of this article to debate the wider implications of the poem’s original material setting, but suffice to say that regardless of its pre-digital existence, the poem’s form and its (current) medium of publication are certainly specific to a networked online environment. A “technotext” as famously defined by N. Katherine Hayles is a work where “the technology that produces” the text is tied “to the [text’s] verbal constructions” (Hayles, Writing Machines 25-26). While it is of course possible to produce a ten-syllable line per day without a digital platform, the generation of meaning through signifying form in Holes relies on its supple digital interface. Manovich, too, has underlined the mutable nature of online spaces:

Web sites are never complete […] They always grow. New links are continually added to what is already there. It is as easy to add new elements to the end of a list as it to insert them anywhere in it. All this contributes to the anti-narrative logic of the Web. If new elements are being added over time, the result is a collection, not a story. (Manovich 220-221)

This extends to how the poem’s extended use of spatial metaphor problematizes the motif of landscape: a collection of images, lines, observations and entries subjected to the requirements of the database can no more form a panoramic representation of the perceptual environment than it can fulfill the requirements of a continuous narrative. This is not to dismiss Hayles’s argument on a symbiotic relationship between database and narrative, where narrative always makes a return as soon as “meaning and interpretation are required” (Hayles, “Narrative and Database” 1603). However in the case of Holes, the database form explicitly challenges narrative as the fundamental mode in which a poem’s relationship to its environment should to be understood.

But Holesis also unmistakably conscious of its pre-web predecessors. The use of a microblog format for publishing Holes pushes poetry into the digital domain in a way that may not longer be exactly radical, but is still relatively rare in Irish poetry and poetic culture. Yet the poem’s autobiographical or even journalistic aspects connect it with the work of a number of modern Irish poets that have examined the relationship between the personal journal and the crafted lyric, including Louis MacNeice in “Autumn Journal” and Paul Muldoon in The Prince of the Quotidian. But even more importantly for the argument here, Allen’s literary aesthetics manifests some striking similarities with the works of Randolph Healy, Trevor Joyce, Billy Mills, and Catherine Walsh, whose approaches to place and landscape can be seen to anticipate the digital poetics of Holes in the context of 20th (and 21st) century Irish poetry. Understanding the formal and stylistic strategies of some of the non-digital antecedents of Allen’s project helps illustrate how its digital aesthetic abandons narrative progression through the use of database logic, as well as the consequences of this shift to the literary representation of landscape. Inasmuch as “[many] creators of digital literature would acknowledge that their work is experimental, and they might implicitly or even explicitly accept the label avant-garde” (Engberg and Bolter 2), the “end of landscape” in Holes can be illuminated through its connections with the (admittedly small and fragmented) Irish community of avant-garde poetry.

The question of genre illustrates the point. Holes is described as a “long poem” by its author and publisher largely in a purely quantitative sense: it is, quite literally, quite long – in principle, it could become the longest poem ever written by a single author, though its eventual length is obviously not yet known. Yet the long poem necessarily undergoes a transformation in an online setting. The entry for “2014-10-27” declares: “This is not a long narrative poem,” and this has less to do with the poem’s length or its occasional portrayal of narrative elements (if not a sustained storyline), than with an awareness of the historical literary genre of the narrative long poem, with close ties with the category of landscape. In Ireland in particular, a number of 20th century poets were “attracted to the idea of the epic as ‘national form’” and thus also “[embraced] the long poem […] as an ultimate test of the worth of a poet and poetry itself” (Goodby, Irish Poetry 100). More often than not, this relied on verbal engagement with landscape, famously encapsulated in John Montague’s The Rough Field, which considers “the whole landscape a manuscript / We had lost the skill to read” (Montague 108). In short, landscape in poetry, has been repeatedly employed as an extended metaphor for historical narratives of colonial dispossession.

Authors have also frequently sought avenues for circumventing these kinds of narrative landscapes in poetry. Alex Davis’s discussion of the neo-avant-garde poetry of Healy, Joyce, Mills and Walsh demonstrates their resistance to the narrative approach, and also helps elucidate the turn away from landscape in Holes. Randolph Healy’s 1997 chapbook Arbor Vitae echoes Montague as it distances itself from an archaic, scribal textuality to explore the materiality of text itself, through the vocabulary of late 20th century word processing technology: “theirworld a document / laid out all around you, / key-text centred, bold underlined” (Quoted in Davis 14). Healy similarly discards tribal landscapes in favor of a (literal) textual terrain, which is constituted by typographical markers on a page. Catherine Walsh’s dinnseanchas2 or place name poems frequently use catalogs, lists, and repetition to challenge romantic/modernist place name poems in the first person lyric mode. Walsh’s later work in particular is drawn to “layers of geographical / aggregates compacted / in the slightest grain” and a “stratification of experience / no narrative” (in Davis 89). Trevor Joyce’s Without Asylum and Billy Mills’ Properties of Stone pitch the materiality of the written text against physical materiality of land or soil. Joyce’s career in IT, and his work as a Business Systems Analyst at Apple from 1992 onwards has been reflected in his desire to write poetry that would “register the ‘flow’ of information in the modern world” while discarding “the mannered narrative [he] so distrusted” (Joyce in Goodby, “Through My Dream” 111). Mills’ poetry, too, merges “aesthetic” and “geological” preoccupations. In “the stony field” (surely echoing the title of The Rough Field), Mills compares the poet not to the archaeologist but to the scientist, repurposing extracts from Charles Darwin’s 1881 essay “The Formation of Vegetable Mould Through the Action of Worms” to describe “the slow accretion / of detail / things made over / reused, renewed” (ibid.). In these poems, accumulation, repetition and processes of gradual transformation of matter replace cultural/historical narrative representation.

This discarding of referential narrative linearity and representation with a poetics of accumulation and materiality is akin to Manovich’s characterization of the new media ecology of a database as “a collection of items” (218). It is a list of individual objects with no explicit narrative continuity, as databases “don’t have beginning or end” (Manovich 218), “end” here denoting a specific purpose, as well as a point of termination. Printed poems cannot enact the accumulative processes through time, with the same flexibility as their digital coutnerparts, but a constantly updated digital poem can expand with no pre-determined end date. Therefore it can never fill, or form, an entirely predetermined space or structure and continues its slow growth on its website, enacts a slow process of accumulation, of “stratification” and “layering,” analogous to the processes described in its printed predecessors. It will end if the technology supporting it becomes redundant, when its author’s life comes to an end, or if he simply suddenly ceases to write it. But it has no end in the sense of “intention,” “aim”, “goal”, or “point of arrival.” The end is not there as a visible horizon, before it is actually encountered. In other words, as a list of entries and detailed observations, and lacking a quotable core or narrative “end,” Holes discards an underlying narrative development that would help “organize” its entries “into a sequence,” as Manovich phrases it (192). Its individual lines, even with their frequent temporal attachements with specific locations, will never allow us to dwell in a scenic panorama.

III

In a web environment, identifying Holes as a poem raises questions of cultural and aesthetic categorization and status, with further implications on what Benjamin described as the aesthetic and experiential “aura” of art, and landscape (Ebbatson 13). The poem’s medium of publication also forces us to revisit the question of how we understand poetry - or poetic discourse. Numerous single-author and collaborative Twitter narratives, for example, follow both the strict limits of a 140-character tweet and the flow of a fictional storyline.3 Holes also resembles “micro poetry” on Twitter, by now quite popular even among poets who may not otherwise publish primarily in digital formats.4 Allen himself has expressed his awareness of the problem of definition, noting in a recent interview that “to call [Holes] a poem makes it sound like it’s a part of a bigger thing, whereas in actual fact it’s the thing itself” (Galvin). In the context of early 21st century digital poetry, Holes is by no means situated at the most technologically adventurous or complex end of the spectrum, as its author and publisher readily admit: “from a technical perspective, Holes […] is arguably unsophisticated” (Allen and O’Sullivan). It uses a simple blog platform (since earl 2017, the publisher has opted for a Dimension HTML5 theme), and reads like a hybrid between a blog and a Twitter feed. But it requires no interaction between author and reader through its interface, unlike many other digital works making use of social media spaces and interfaces (for an overview of the history of social media poetics, see Malloy). Its strictly ten-syllable lines also echo the tradition of metrically controlled lyric form (it is impossible to ignore the ghost of the iambic pentameter in the choice of ten syllables for a daily quota). Formal control in poetry has, here and elsewhere, presented opportunities for both experimentation and for compliance with routine forms of expression. To quote Anastasia Salter, a tension exists between “intentional writing under constraint [and] simply following the traditional rules governing communication or working with a medium” (Salter 533). Holes demonstrates an awareness of both in its use of a chosen constraint, and a similar renegotiation of tradition through repurposed aesthetic choices also characterizes its engagement with the motif of landscape.

A ten-syllable line of poetry published and disseminated via a social media platform nods towards high cultural production, yet renders the speaking voice rather mundane. In this sense, Holes can be examined as a simultaneous acknowledgement and refusal of the lyric process, described by Marjorie Perloff as one presenting “an isolated speaker […] located in a specific landscape, meditating or ruminating on some aspect of his or her relationship to the external world, coming finally to some sort of epiphany” (Dance, 156-157). Its chosen microblog format of a microblog is defined by Brian Croxall as “a practice that applies a size constraint to the content of blogs,” and “the term primarily refers to posting that takes place on specific platforms whose design either encourages or enforces brief communication” (492). Such short forms are characteristic of born-digital autobiographical prose, a public, online equivalent of diary or journal writing. And while Jill Walker Rettberg has contrasted the quantitative forms of self-representation (lists, graphs, and similar forms) and various modes of record-keeping with the primarily narrative form of a diary (9), it would be more accurate to say that microblogging in the sense defined by Croxall is somewhere between narrative self-expression and quantitative tracking of activities. Inasmuch as the poetry of the Irish neo-avant-garde retains, as Alex Davis observes, the “exoskeleton of the lyric I” (91), Allen’s autobiographically motivated digital poem, too, still at least acknowledges the gravitational pull of the first person subject.

Yet this subjectivity is ultimately moderated, rather than entirely relinquished, by the literary aesthetics of the database as a “new form to structure our experience” (Manovich 219). Like Hayles, Jessica Pressman has also stressed how “the relationship between database and narrative, process and product, form and content, is intertwined and inseparable” (Pressman 102). Holes, too, consists of brief and occasionally narrative fragments, as it comments on daily events and experiences, alongside the strictly quantitative element that poses no requirement of spatial or narrative continuity (ten syllables a day, one line for each day, with no thematic structure). Croxall emphasizes that “[given] the short nature of individual posts to microblogs, many of them emphasize what the creator is doing, reading, finding, looking at, or thinking about at a particular moment,” and that this “ephemeral nature of the content on micro-blogs leads many people to question the value of what is shared with a tool like Twitter” (Croxall 493, variation in spelling in the original). Such expression stands in stark contrast to the “aura” of lyric poetry in print. In other words, the “ephemeral” quotidian moments in microblogs, are the opposite of the distilled moments of transcendence that characterize the romantic lyric. This sense of commonplace everyday life is only emphasized by the constant referenced to its opposite in Holes, through the several entries referring to the work of Wordsworth, Shelley, Keats, Blake, and Byron.

Consequently, a long poem without a center or narrative continuity, consisting of brief observations, must make a case for its own significance or “literariness” through a different kind of process. Coxall argues that “the usefulness of microblogging does not lie in the single post or photo. Instead, a person’s posts become useful when taken in the aggregate” (494). In other words, the short form has to become “long” before its details develop meaningful patterns – not through distilling the quotidian into brief moments of epiphanic clarity, and organized into a narrative sequence, but by allowing itself to gradually build up into a more complex terrain. “Something emerges,” Allen himself notes, “when you put all of these holes together; what emerges is a kind of pattern” (Galvin). It is the interplay between the very short and the very long through database form that also undermines the idea of landscape as a panoramic vista viewed at a glance, or as a narrative embodiment of a socially and personally constructed narrative. Instead, we are offered a series of snapshots that build up into wider network, and reveal new meanings through their relationship with newly added material. This dynamic is enacted through the expanding text of the poem, but also through the visual material that accompanies it.

IV

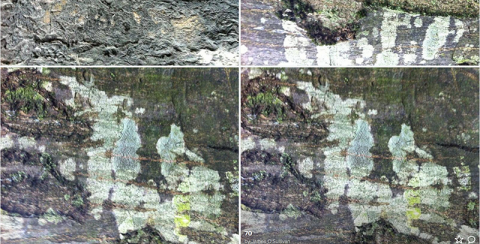

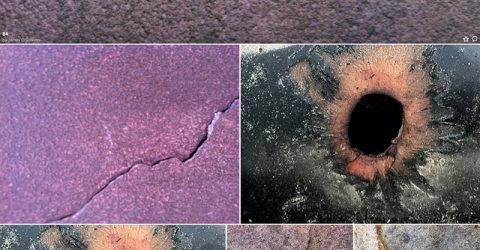

The text of Holes is published alongside close-up photographs of stone layers, chipped and cracked wall surfaces, and rock formations on a separate gallery page (previously on the same website but now available via a link to a Flickr page) (see Figure 1). The photographs are posted with less regular intervals than the poem’s text, and at the moment of writing this article, the gallery page includes altogether 265 images. The painted and unpainted stone and wall surfaces are made of uneven materials, with lines and crevices, layers of sediments, holes, flaking paint, dents, and stains on them (see Figure 2). The text of the poem itself does not directly respond to or comment on the photographs, and they consequently serve as a kind of visual correlative to the verbal dynamics of the poem, or offer a spatial/visual metaphor for its aesthetic and philosophical concerns. The sediment layers visible in some of the rock surfaces, with the newest stratum on top (similar to the lines of the poem), are accumulated on top of each other slowly, over time.

Figure 1

Figure 1

The photographs in the gallery thus reiterate the poem’s relationship to the perceptual/material world, and its withdrawal from landscape as vista, replacing it with a process of repetition and accumulation of disparate elements. They also render the connection with the above discussed poems by Healy, Mills and others even more explicit, evoking the “the slow accretion / of detail” of “a stony field,” or Walsh’s “layers of geographical / aggregates.” The photographs are zoomed in too close for a wider context; they are viewed though “an aperture so small as to permit little light” (Allen and O’Sullivan). They present a tiny fragment of the surface material, usually enough to see whether the surface is man-made or natural, but little more than this. In other words, while they depict the material components of a landscape, no landscape is available to the reader/viewer: similarly to the individual ten-syllable lines, their perspective is too limited for a broader view. Yet a more extensive topography builds up gradually, as previous images connect with new material, and any detectable patterns may result from the accumulation of details over time, just as the lines on some of the rock surfaces are formed by sediment layers. Through the photographs, the aesthetics of the database is evoked visually as well as verbally, and doubly so: the gallery page forms a database or archive of its own. It enacts the presentational form of the pre-digital photo album which, as Manovich notes, already adopted “a database-like structure” (220).

Figure 2

Figure 2

In the text of the poem only one line explicitly addresses the photographs, and it appears alongside one of the poem’s few explicit references to Irish landscape. The perspective rarely zooms out for a snapshot of a wider expanse of space, but when this happens, the tone self-consciously emphasizes the act of viewing and representation itself: the perceived world is presented as focalized and made strange by a human observer, and language. The scenic vistas of Holes are specified as County Kerry, perhaps the most popular destination for tourists in search of the authentic Irish landscape of green mountains and seashores: “2009-10-24 Kerry was further away than it looked. / 2009-10-25 The lakes and the beaches, strangely unreal,” “2013-04-26 Let’s run away over Kerry mountains. / 2013-04-27 Back to that place of camera-friendly stones.” Kerry landscape itself would, by many, be considered as extremely “camera-friendly,” and visual representations of the west of the Ireland mountains and seaboard have a long history of foreign and indigenous attempts to capture the essence of the Irish territory as an embodiment of national and cultural character. But instead of authenticity, the lines emphasize the landscape’s “unreality” and mediated photographic nature, and focus on close-up photographic detail. In the only mention of the word “landscape” in the poem, the speaker observes: “2007-08-26 Ontology seeps out of the landscape.” A reference to “ontology,” the metaphysical concept addressing the nature of being, would suggest that the essence of the landscape is a quality somehow intrinsic to it, and that a closer observation of its materials could offer a deeper insight into its cultural/national chracter – an idea that the ironic tone of the line undermines. In its current usage, the concept of landscape only emerged in the 16th century in the context of aesthetic developments in the visual arts, and in this sense it is not an entity that would exist independently of the human observer. The photographs thus force us to recognize how visual and narrative coherence in any visual or verbal engagement with landscape takes place in the act of representation, never within the physical world itself. The limited scope of its short lines and the photographs repeatedly stops short of expanding to the renaissance scholar Alberti’s famous image of finestra aperta, or open window. But the poem’s rejection of the trope goes even further than that; rather than offering multiple perspectives or fragmented viewpoints, Holes refuses the very idea of a (literal and figurative) distance required to perceive any wider terrain..

V

Both historically and in the contemporary context, a considerably body of literature and critical writing engages with the Irish landscape as a historically informed discursive terrain of cultural specificity (see for example Frawley, and Smyth) – this framework also applies to much writing on literature and culture outside this specific national context. It is through landscape that poetry has repeatedly made a claim to cultural specificity, personally and communally. Yet Holes demonstrates little if any interest in such an approach, and signals an end of landscape as it moves away from what Trevor Joyce calls the trope of “Irish Terrain”, oscillating between the rare moments of self-conscious acts of perception and images of extreme material detail, or presenting a long, growing series of diminutive apertures as a stated withdrawal from the scene mode. Its fascination with gaps, cavities, punctures, vents, blind spots, fissures, and absences marks a discomfort with concepts like subjectivity and poetic voice. Instead, Holes is preoccupied with the limits of its existence, and turns its attention towards the accumulative and disobedient minutiae that refuse to settle in a pre-determined narrative or temporal framework.

The logic of the database underlines this discordance. This aesthetic also sets Holes apart, despite its shared imagery of geological strata, from modernist authors’ use of spatial metaphors of geological and archaeological imagery to evoke psychological depth, in Ireland and elsewhere. Brian McHale for example has discussed how modernism went though a “spatial turn” of its own as artists and writers were drawn to the master-trope of “the spatial dimension of verticality or depth,” particularly prompted by Sigmund Freud’s use of “archaeological tropes for the ‘stratified’ structure of the psyche and the ‘excavatory’ work of psychoanalysis” (“Archaeologies” 240). The trope was explicitly used by the Irish modernist writers Samuel Beckett and Thomas MacGreevy, who joined their European peers in the 1932 manifesto “Poetry Is Vertical.” The “multiple stratifications reaching back millions of years” were seen as “brought to the surface with the hallucinatory irruption of images in the dream […] and even the psychiatric condition” (Arp, Beckett & al. 73). The “ephemeral,” quotidian, and at times even comic nature of the individual microblog entries prevents the poem from turning into an exercise in high modernist aesthetic, a monument made of carefully selected fragments shored against the ruins of an individual psyche. Such tropes are undercut rather than enforced by a constraint that enacts a similar process of stratification, yet discards the idea of depth-as-narrative, and the tragic melancholy for absent order, on which modernist poetic landscapes so often rely.

Finally, Holes also suggests a manner in which poetry using digital platforms necessarily comments on its own philosophical and sociocultural underpinnings. Stuart Boon and Christine Sinclair, in a rather dejected tone, note that “digital selves have become fractured, confused reflections of a person, never wholly unreal, but never wholly real either – a seeming half-truth” (19). But if selves in online environments are, as Claire Lynch phrases it, “sites of potential identity crisis,” one could argue that such a crisis is also an inseparable from the genre of lyric poetry. Through the “symbolic form” of the database, poetry can find one possible means to examine how mediated selves are constructed through a series of encounters with the material and the phenomenal experience, language and text, slowly accumulating into a more extensive autobiographical topography, without and end, “until the end.”

Works Cited

Allen, Graham. Holes. Web. 25 May 2017. .

---. “395 Holes.” Theory & Event 12.1 (2009). Web. 9. Dec. 2015. .

Allen, Graham and James O’Sullivan. “Collapsing Generation and Reception: Holes as Electronic Literary Impermanence.” Hyperrhiz 15. Web. 20 Dec. 2016. .

Arp, Hans, Samuel Beckett, Carl Einstein, Eugene Jolas, Thomas MacGreevy, Georges Pelorson, Theo Rutra, James J. Sweeney, and Ronald Symond. “Manifesto: Poetry Is Vertical.” The Collected Poems of Thomas MacGreevy. Eds. Thomas Dillon Redshaw. Dublin: Raven Arts Press / New Writers Press, 1971. 73-4. Print.

Boon, Stuart and Christina Sinclair. “A world I don’t inhabit: disquiet and identity in Second Life and Facebook.” Educational Media International 46.2 (2009): 99-110. Print.

Casey, Edward S. Representing Place: Landscape Painting And Maps. Minneapolis (MN): University of Minnesota Press, 2002. Print.

Coxall, Brian. “Twitter, Tumbler, and Microblogging.” The Johns Hopkins Guide to Digital Media. Eds. Marie-Laure Ryan, Lori Emerson, and Benjamin J. Robertson. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2014. 492-96. Print.

Cripps, Charlotte. “Twihaiku? Micropoetry? The rise of Twitter Poetry.” Web. 10 Nov. 2015. .

Davis, Alex. “Deferred Action: Irish Neo-Avant-Garde Poetry.” Angelaki, Journal of the Theoretical Humanities 5.1 (April 2000): 81-93. Print.

Ebbatson, Roger. Landscape and Literature 1839-1914: Nature, Text, Aura (Houndmills, Basingstoke: Palgrave MacMillan, 2013). Print.

Edwards, Marcella. “‘A scheme of echoes’: Trevor Joyce, Poetry and Publishing in Ireland in the 1960s.” Critical Survey 15.1, Anglo-Irish Writing (2003): 3-17. Print.

Edwards, Marcella and John Goodby. “‘Glittering Silt’: The Poetry of Trevor Joyce and the Myth of Irishness.” Hungarian Journal of English and American Studies 8.1, Irish Issue (Spring 2008): 173-98. Print.

Engberg, Maria and Jay David Bolter. “Digital Literature and the Modernist Problem.” Digital Humanities Quarterly 5.1 (2001). Web. 1 Mar. 2016. .

Galvin, Mary. An interview with Graham Allen, Cultural Mechanics podcast. Produced by James O’Sullivan. Web. 20 Feb. 2016. .

Goodby, John. Irish Poetry since 1950: From Stillness into History. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2000. Print.

Hayles, Katherine N. Writing Machines. Cambridge (MA) and London: MIT Press, 2002. Print.

—. “Narrative and Database: Natural Symbionts,” PMLA 122.5, ‘Remapping Genre’ (October 2007): 1603-1608. Print.

Joyce, Trevor. “Irish Terrain.” Assembling Alternatives: Reading Postmodern Poetries Transnationally. Ed. Romana Huk. Middletown, Connecticut: Wesleyan University Press, 2003. Print.

Lynch, Claire. Cyber Ireland: Text, Image, Culture. Houndmills, Basingstoke: Palgrave MacMillan, 2014. Print.

Malloy, Judy. Ed. Social Media Archeology and Poetics. London and Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2016. Print.

Manovich, Lev. The Language of New Media. London and Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 2000. Print.

Mays, J. C. C. “Flourishing and Foul: Ideology, Six Irish Poets and the Irish Building Industry.” Irish Review 8 (1990): 10-3. Print.

McHale, Brian: “Telling Stories Again: Replenishment of Narrative in the Postmodernist Long Poem.” The Yearbook of English Studies 30 (2000): 250-62. Print.

---. “Archaeologies of Knowledge: Hill’s Middens, Heaney’s Bogs, Schwerner’s Tablets.” New Literary History 30.1 (1999): 239-62. Print.

Montague, John. Selected Poems. Toronto: Exile Editions, 1991. Print.

Moore, Matthew. “The Longest Poem in the World Written on Twitter.” The Telegraph 21. August 2009. Web. 10 Dec. 2015. .

New Binary Press. Publisher’s website. Web. 9 Dec. 2015. .

Olwig, Kenneth N. “Recovering the Substantive Nature of Landscape.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 86.4 (1996): 630-53. Print.

O’Sullivan, James. “Electronic Literature: A Publisher’s Perspective.” Conference presentation at ELO2015: “The End(s) of Electronic Literature.” University of Bergen, 6 Aug. 2015.

Perloff, Marjorie. Wittgenstein’s Ladder: Poetic Language and the Strangeness of the Ordinary. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1999. Print.

---. The Dance of the Intellect: Studies in the Poetry of the Pound Tradition. Chicago: Northwestern University Press, 1996. Print.

Pressman, Jessica. Digital Modernism: Making it New in the New Media. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014. Print.

Salter, Anastasia. “Writing under Constraint.” The Johns Hopkins Guide to Digital Media. Eds. Marie-Laure Ryan, Lori Emerson, and Benjamin J. Robertson. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2014. 533-36. Print.

Smyth, Gerry. Space and the Irish Cultural Imagination. New York: Palgrave, 2001. Print.

Thomas, Bronwen. “140 characters in search of a story: Twitterfiction as an emerging narrative form.” Analyzing Digital Fiction. Eds. Alice Bell, Astrid Ensslin, and Hans Kristian Rustad. London: Routledge, 2014. 94-108. Print.

Wagner, Jennifer Ann. A Moment’s Monument: Revisionary Poetics and the Nineteenth-century English Sonnet. Madison (NJ): Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 1998. Print.

Walker Rettberg, Jill. “Writing Photographs (#1YearNoCam).” Web. 10 Dec. 2015. .

---. Seeing Ourselves through Technology: How We Use Selfies, Blogs and Wearable Devices to See and Shape Ourselves. London: Palgrave MacMillan, 2014. Print.

Wylie, John. Landscape. Abingdon, Oxon, and New York: Routledge, 2007. Print.

Footnotes

-

The definition was given by the geographer Richard Hartshorne in his 1939 volume The Nature of Geography (quoted in Olwig 630), but has since been reiterated by a number of geographers. Edward S. Casey also characterizes landscape as “a portion of the perceived earth that lies before and around us” (xiii), and for John Wylie “landscape is a particular way of seeing and representing the world from an elevated, detached and even ‘objective’ vantage point” (Wylie 4). ↩

-

This term, which literally translates as “lore of the place” refers to a bardic Gaelic language oral tradition of place-name poetry (for a more detailed description see e.g. Smyth 47). ↩

-

On Twitter fiction, see for example Thomas 94-108. ↩

-

On the popularity of Twitter poetry, see for example Cripps. ↩

Cite this article

Karhio, Anne. "The End of Landscape: Holes by Graham Allen" Electronic Book Review, 3 June 2017, https://doi.org/10.7273/c2j2-ra97