The King and I: Elvis and the Post-Mortem or A Discontinuous Narrative in Several Media (On the Way to Hypertext)

Niall Lucy enacts a writing that weaves critical and theoretical speculation, rock journalism, hagiography and autobiography.

Niall Lucy enacts a writing that weaves critical and theoretical speculation, rock journalism, hagiography and autobiography.

(For David McComb)

The other day I picked up the phone and a voice said hello is that Pete and I said no you’ve got the wrong number and the voice said how do you know I’ve got the wrong number and I thought, wow … a media theorist!

Music: The Black-Eyed Susans, ‘Viva Las Vegas’ (Song Sample available here)

I can’t sleep nights for feeling paranoid. I used to think it was just the sideburns, but now I’m not so sure. Not after putting it to the test.

I tried to leave nothing to chance, even deciding to order macchiatos instead of my usual long blacks. To disguise myself I went barefoot in a pair of loose-fitting Yakka trousers (green) and sloppy T-shirt (black), and bought a packet of Drum. I took with me a Kathy Acker novel and a notepad, for my own writing, and sat around at Gino’s waiting to see whether it would happen again.Gino’s Café in Fremantle, Western Australia - favored haunt of the local hippies and the alternative set.

It did.

I hadn’t finished my second mac when someone, a stranger like all the rest, walked over to my table and asked for a light. I nodded at the Zippo in front of me. Suddenly I was angry with myself for not having bought a Bic, but I couldn’t imagine a cigarette lighter as the object of my undoing. It had to be something more essentially connected to who I am … something about me that no disguise, however careful, could conceal.

Then it happened.

The stranger lit his cigarette, a Winfield, handed back my Zippo and said: ‘Great lighter, Elvis. Thanks.’

Elvis? I couldn’t have looked more Fremantle, I thought, but there must have been something about me that was saying “Las Vegas.” To the stranger, at any rate, who was dressed indistinguishably from me. Even when I looked like a writer, somehow I still looked like the King.

I can’t sleep nights for feeling paranoid.

For some time now I’ve been the subject of Elvis sightings, in and around Fremantle. Either I don’t know who I am any more, or the people who think I’m Elvis don’t know who Elvis is. Or I’m imagining that I’m the subject of Elvis sightings - in which case I might be in need of an analyst. Or there’s a conspiracy, among (some) people in Fremantle, to make me imagine I’m the subject of Elvis sightings. Or I’m imagining there’s a conspiracy among some people in Fremantle to make me imagine I’m the subject of Elvis sightings. Those are my choices, tormentingly like the ones put to Oedipa Maas in The Crying of Lot 49.

Oedipa calls them ‘those symmetrical four. She didn’t like any of them, but hoped she was mentally ill; that that’s all it was.’ (Pynchon, 1979) Of course that’s what she hoped it was, a psychological disorder. Far better the Oedipus than the Oedipa complex, after all. Better that your mind be bent by patriarchy, or some other disturbing force, than to discover the patriarchal as a discourse with no outside. If all plots are boys’ games, and plots are everywhere, how could they be unravelled? Indeed, how could they even be recognised as boys’ games in the first place? How to get outside the patriarchial, if patriarchy is the source and means of your oppression, in order to be critical of what’s determined the range and facility, and set the agenda, of your thinking - if you’ve been taught to think yourself (always unknowingly) only as the oppressed?

How, in other words, to think otherwise?

Which isn’t quite Oedipa’s dilemma, of course. But close. Her problem is that she can’t decide whether an occult postal system called the Trystero, whose operations may have determined the course of Western history, is real or not. If it’s real, then our history isn’t - for what we think of as historical reality would need to be rewritten in the light of Oedipa’s “discovery.” If, on the other hand, the Trystero isn’t real, then Oedipa must have imagined it into some kind of determinate existence, at least inside her head. Either it’s outside her head and real, then, or not and therefore a fantasy. On the other hand, again, it might be outside her head, but as someone’s idea of a practical joke. After all, it’s in her role as the executrix of her ex-lover Pierce Inverarity’s estate that Oedipa first comes across the Trystero as plot. So if the plot’s a practical joke it must be of Pierce’s doing, requiring the collusion of his friends and lawyers to make it work. A conspiracy, then, to get Oedipa to believe the Trystero is real. On the other hand, yet again, she could be imagining such a conspiracy. Hence ‘those symmetrical four’.

By the same token there would be nothing to stop this sequence (‘there is a plot … there is a plot that there is a plot’ … and so on) from repeating and multiplying itself, although Oedipa’s made to feel paranoid enough without having to put that to the test (Thwaites, 2000: 269). She finds just four alternatives quite sufficient to be unable to decide.

Me, too, for that matter. You try getting to sleep at night not knowing whether you’ve been mistaken for Elvis, or whether there’s a plot, or you’ve imagined there’s a plot, to make you imagine you’ve been mistaken for Elvis. Seems simple enough: the Elvis sightings are real, or there’s a plot. It’s happening, or I’m crazy. Cross-paired (real/imagined; Elvis sightings/plot), these four terms constitute a closed system, a choice between opposites: either the real or the imagined; either the sightings or the plot. But what if the sightings themselves are part of a plot, even if they’re ‘real’ (however hopelessly inadequate that term has become in the present context)? Surely if I am being mistaken for a dead man, what else can I be but the subject of a grave plot? A case of the postmodern as the post-mortem, perhaps.

Music: Elvis, Edge of Reality

Chances are that those in Fremantle who keep on mistaking me for the King never met Elvis personally. Nor could it be very likely that many people in Fremantle ever saw Elvis in concert. Whatever stands in for a knowledge of Elvis by such people couldn’t have derived from outside representations - let’s call them media representations - in the form of records, movies, posters, calendars, greeting cards, interviews, TV shows, concert footage and the like.

That’s how most of us “know” any pop star, of course. But we’d hardly call Elvis Presley just another pop star, if only because the fluidity (or perhaps the vectrality) through which his name circulates across divisions of class, gender, age, ethnicity (there’s a Chinese and a Hindi Elvis impersonator doing very nicely in London at the moment, apparently), education, taste and so on puts him (or should that be “it”?), like “William Shakespeare,” in a category apart from his peers.See Wark, McKenzie. Virtual Geographies: Living With Global Media Events (Indiana University Press: Bloomington, 1994) - and everything since. (On which score I’m reminded of a “test” once performed in an undergraduate lecture I attended in a course on Jacobean drama. The test was designed to ‘prove’ that Shakespeare is the greatest dramatist of all time. It went like this: ask a Russian to name the world’s two best playwrights and he’ll tell you Chekov and Shakespeare. A Frenchman will say Moliére and Shakespeare. A German, Göethe and Shakespeare. Someone from Scandinavia will say Ibsen and Shakespeare … and so on. Ergo, Shakespeare is the greatest dramatist of all time. End of lecture.)

The conflation of the best known with the best is a commonplace of cultural criticism. Let’s face it, 50 million Elvis fans can’t be wrong, and all those high-school courses everywhere devoted to an appreciation of the Bard just go to show the timeless quality of his plays and the essential genius of the man himself. So the argument runs. Paradoxically, however, it can also be made to run the other way - against an artist or an object considered to be too popular to be of genuine aesthetic worth. Those 50 million Elvis fans, for instance, precisely because they do transgress so many demographics, serve to demonstrate the ephemerality of Elvis’s appeal, based as it must be on an all too common aesthetic denominator to warrant serious intellectual and moral attention - except by way of disapprobation. Which has nothing to do with Elvis, either. Before Elvis, straight society was freaking out at Frank Sinatra - just as, before Sinatra, it had got hysterical about jazz. Nowadays the fear and loathing brigade is made to feel righteous by hip hop and heavy metal bands - not by Elvis, who really hasn’t scared anyone (except during the hour-long broadcast of his 1968 NBC-TV special, often called his ‘comeback’ special) since he came out of the army in 1960. By that decade’s end, his audience lost to Dylan, the Mersey beat, and the psychedelic sounds of San Francisco, EP was well and truly out of touch with the Woodstock generation. He’d become too rich to be radical, too much of a public figure to be hip. Worst sign of all, perhaps: everyone knew the name of Elvis’s manager, Col. Tom Parker.

Dream sequence…

I’m alone inside Gino’s at night. Only it isn’t Gino’s: it’s what Gino’s would look like if Salvador Dali had been hired to do the decor. Everything’s liquid and warped. Suddenly, a man wearing a gold lamé suit walks in and sits at my table. I start feeling paranoid. I can sense that he wants me to look into his eyes, but I look down at my hands instead. Then he starts to sing. He’s got a powerful voice but I have to strain to hear the words. ‘I must have been mad’, he’s singing like he means it. ‘I didn’t know what I had/Until I threw it all away.’ I recognise the song from Dylan’s Nashville Skyline, but the voice is pure Elvis. I stop feeling paranoid. My body shivers in pain and delight. The voice has me enraptured. My God, I’m listening to the greatest Elvis impersonator on earth! I look up to see his face, and find myself staring into the vacuum of a woman’s eyes.

I wake all nervous and exhausted in a pool of sweaty fluids.

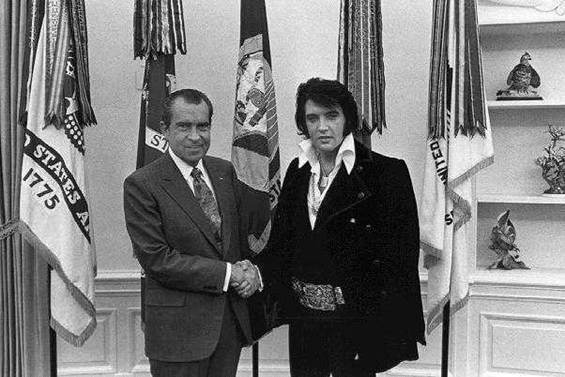

There’s a great story about Col. Tom, surrounding one of the most bizarre moments in American politics of 1970: Elvis being made an honorary Federal narcotics agent by Richard Nixon in the Oval Room of the White House. That part’s true. The story’s told by rock critic Stu Werbin, but I know it only from a footnote in the ‘Presliad’ chapter of Greil Marcus’s Mystery Train: Images of America in Rock ‘n’ Roll Music - still one of the best things ever to be written on Elvis:

It seems that the good German who arranges the White House concerts for the President and his guests managed to travel the many channels that lead only in rare instances to Col. Tom Parker’s phone line. Once connected, he delivered what he considered the most privileged invitation: The President requests Mr. Presley to perform. The Colonel did a little quick figuring and then told the man that Elvis would consider it an honor. For the President, Elvis’s fee, beyond traveling expenses and accommodation for his back-up group, would be $25,000. The good German gasped.

‘Col. Parker, nobody gets paid for playing for the President!’

‘Well, I don’t know about that, son,’ the Colonel responded abruptly, ‘but there’s one thing I do know. Nobody asks Elvis Presley to play for nothing.’ (Marcus, 1976: 137-8)⏴Marginnote gloss1⏴Larry McCaffery writes of Elvis as a montage-artist in his ebr essay “White Noise/White Heat” on the postmodern in rock ‘n roll: he instinctively combined various American musical idioms (black gospel, blues and rhythm-and-blues, and white country-and-western) into a distinctively new form.

Larry McCaffery writes of Elvis as a montage-artist in his ebr essay “White Noise/White Heat” on the postmodern in rock ‘n roll: he instinctively combined various American musical idioms (black gospel, blues and rhythm-and-blues, and white country-and-western) into a distinctively new form.

— Lori Emerson (Jul 2007) ↩

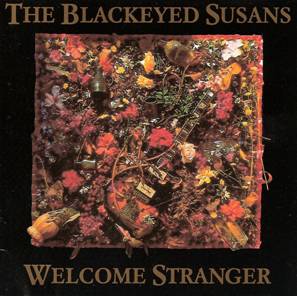

Apocryphal or not, such stories had a very real effect on what Elvis had come to mean by the mid-1960s. They served to reproduce for his “life” what the hip public had come to understand of his work: that it was emotionally crass and driven by a lust for power and money. Listen to this description of Graceland, for example, as sent to me by my friend Rob Snarski, from the Black Eyed Susans, on a postcard of Elvis’s grave:

Dear Niall,

Well I’ve seen it. The King’s final resting place and his home of twenty odd years. In fact Jason, Mark & I spent a good 6 hours at Graceland & the various museums and giftshops. The “jungle room” filled with Hawaiian furnishings which the big E chose and purchased in 30 minutes and the very same room he recorded ‘Moody Blue’ was particularly tasteful. The T.V. room with 3 wall-mounted television sets, so as ‘Tiger’ (as his closest friends called him) could watch three football games simultaneously had a rather striking color combination of yellow and blue and a delightful mirrored ceiling. And who could forget the gorgeous white ceramic monkey on the coffee table?! The music room, the pool room, his living room, The Lisa Marie (the very same plane he took some buddies to Denver in to eat peanut butter sandwiches) and his automobile collection … yep we saw it all. Then the following day we visited Sun studios and drove to Tupelo to see E.P.s birthplace. O.K. I think Graceland is a zoo but Sun was really enjoyable, especially hearing snippets of conversation between the ‘Million Dollar Quartet’ [that’s Elvis, Carl Perkins, Jerry Lee Lewis, and (although there’s some debate about it) Johnny Cash]! Then to hear The King imitate a black man he heard singing ‘Don’t be cruel’…

And so it goes. The one called Mark, Rob’s brother, also sent me a postcard from Graceland - a picture of Elvis and Priscilla’s wedding costumes displayed museum-style: sans heads and bodies. Ghostly simulacra of the real. I think even my friends are trying to tell me something.

To return though to the postcard of the grave. What exactly does Elvis’s grave plot commemorate? Why must visiting it take the form of a pilgrimage? Why is a man whose corpse is said to have contained 14 known drugs, who so clearly seems not to have treated his body like a temple, buried in sacred ground? (Think about that: you start losing count after awhile. I mean, how many dangerous substances are there? Coffee, alcohol, cigarettes, uppers, downers, dope: that’s only six. At Elvis’s post-mortem, they found another eight.)

Easy. Because the fucking hippies killed him. Elvis died, not for being a poet but for not being a poet. He died because he could sing.

Video: Elvis, If I Could Dream

Never mind that what we’ve just seen and heard isn’t rock and roll in any pure stylistic sense, that it’s more indebted to black gospel than white hillbilly: its mass entertainment status is enough to condemn it, in certain quarters, for being trivial and sentimental instead of exuding a richness of feeling, complexity of thought and performance, and a serious moral tone. Nor is this account of rock as trivial and trivializing alone in its articulation of a lost origin, its nostalgia for the real, for a lost organic community based on authentic and authenticating experience arising from a stable moral order. Old style lefties, too, condemn rock as ‘false’ culture.

So much, in other words, for Elvis’s utopian dream of ‘a better world’ in the clip from his NBC TV special. Proof positive of the falsity of his politics, performance and art, indeed, came with the single release of ‘If I Could Dream’ in late 1968 which sold enough copies for Elvis to reach number twelve on the US charts, his highest position in years and a sure sign that he was back in commercial action. His very purpose in recording the song, and the TV special it closed, was therefore to boost an ailing career, a career made to suffer from a serious lack of recognition-effect between performer and audience as a result of all those lousy movies Elvis had been churning out for nearly a decade with all those would-be starlet bimbos whose names no one could remember and whose cleavages all looked the same. How could the expression of that dream, to refacilitate the profit-turning wheels of his selling power, to make money at the cost of consumer exploitation, not to mention at the cost of labour - how could that dream be democratic, utopian, shared?

Here, if it were needed, is the proof that it could not:

In this photograph of Elvis looking a lot like Count Dracula on cheap speed and Nixon, as always, looking shifty, is commemorated one of the most bizarre events surrounding American politics prior to Watergate. On 21 December 1970 Elvis was shown into the Oval Room at the White House, bearing gifts for the President of a Colt .45 handgun and a supply of silver bullets. In return, Nixon gave the King a pair of White House cufflinks. Elvis, who is reputed to have been drugged to the eyeballs at the time, totally off his face on some chemical cocktail of otherwise lethal proportion to commoners, then entered into conversation with Nixon on the dangers to American youth of drugs, communism … and The Beatles; and finally revealed the purpose of his visit. He had recently got himself appointed as an honorary agent of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs, and what he wanted from the President - all he wanted - was a Bureau badge. So Nixon gave him one. Their meeting lasted only half-an-hour, enough time for 28 photographs to be taken of one of the most surreal moments in American history. Adding to the surrealism of that event , or perpetuating it, is the fact that copies of those photographs are now the most requested, by tourists and visitors to Capitol Hill, of the ten million pictures in the US National Archives.

Dream sequence…

I’m standing outside the Fremantle Markets, my attention caught between two buskers. Only it isn’t me. I’ve got a Scouse accent and the twisted brain of McKenzie Wark, but thankfully it’s my own hair. One of the buskers is singing Elvis songs, the other is reading Derrida out loud. They’re both women. ‘Genres are not to be mixed’, the Derrida busker reads. ‘I repeat: genres are not to be mixed.’ A small crowd is gathered in front of the Elvis singer, thrusting copies of Catharine Lumby’s Bad Girls at her and screaming: ‘Traitor! Traitor! Woman hater!’ But she just keeps right on singing. Her voice is filled with love and passion, although it has no strictly musical qualities to recommend it - and she’s one hell of a lousy guitar player. Meanwhile, the woman reading Derrida has gone on to ‘Of an Apocalyptic Tone Recently Adopted in Philosophy’. ‘Kant speaks of modernity’, she reads, ‘and of the mystagogues of his time, but you will have quickly perceived in passing, without my even having to designate explicitly, name, or pull out all the threads, how many transpositions we could surrender to on the side of our so-called modernity. Not that today anybody can be recognized on this or that side, purely and simply, but I am sure it could be shown that today every slightly organized discourse is found or claims to be found on both sides, alternately or simultaneously, even if this emplacement exhausts nothing, does not go round the turn or the contour of the place and the sustained discourse. And this inadequation, always limited itself, no doubt indicates the thickest of difficulties.’ Jacques Derrida, ‘Of an Apocalyptic Tone Recently Adopted in Philosophy’, Semeia, Vol. 23, 1982, p. 78. She, too, has attracted a grim crowd of protesters, equally determined to shout her down. Still she reads on, against her would-be interlocutors, dispatching her apocalyptic words in a tone of voice that’s pathological. But the crowd noise prevents me from receiving the full text of her delivery, and what I hear is filled with gaps: ’… as soon as we no longer know … who speaks … the structure of every scene of writing … of all experience itself … it is first the revelation of the apocalypse … of the divisible dispatch for which there is no … assured destination…’ Straining to hear, even so I feel I’m on the brink of an epiphany, of some great revelation scene about to be; at last, the coming of the end, the moment of demystification. Beyond philosophy, outside writing, past play: Truth laid bare! But not yet. The Elvis singer, who’s been marked by her absence for awhile, suddenly starts into a new song. Just as suddenly, the crowd goes quiet. ‘If you don’t believe I’m leaving’, the Elvis singer sings, ‘You can count the days I’m gone’ - and disappears in a mushroom cloud of smoke. Suddenly, at last … the end approaches. The very end. Not a moment of epiphany after all, but of eschatology. I wake up feeling paranoid and, cursing my luck in a voice that isn’t mine, fall out of bed.

Fall out. The aftermath of that event (that plot?) that will send us all to our graves. The post-mortem, perfectly. The final end awaited as if it were the realest real. The realist real? A fiction, then; as morphological as any myth? For nuclear war, as Derrida remarks, ‘has not taken place: one can only talk and write about it […] some might call it a fable, then, a pure invention: in the sense in which it is said that a myth, an image, a fiction, a utopia, a rhetorical figure, a fantasy, a phantasm, are inventions’ (Derrida, 1984: 23). But, at the same time, very serious shit. After all, no one’s going to want to push too hard for a strict equivalence between nuclear war and narrative fiction. (Between missiles and missives, there’s just gotta be a gap.) A choice, then, as it were, between deterring and deferring. Deténte versus denouément. But not quite, or not quite yet. Up against the limits of reason, caught in a moment of perpetual paralysis engendered by the nuclear threat (the end of the Cold War notwithstanding), the logic of nuclear deterrence is unthinkable within a system given to producing sense through context. Simply (monstrously), the fiction stakes increase each time that one side or the other invents a new weapon, some new (however trifling) device, that continues to defer the end from happening but also brings it endlessly closer. Deterrence and deferral at the same time. According to this game, what’s real is what is most fantastic: a game played out between storytellers, storytellings. It’s not a question of scientific know-how, military might, political clout, or diplomatic bargaining but (and this is the gravest plot, the most heavily weighted) of all of these competencies at once, and more. And so Derrida writes:

The dividing line between doxa and episteme [between opinion and knowledge, that is to say] starts to blur as soon as there is no longer any such thing as an absolutely legitimizable competence for a phenomenon which is no longer strictly techno-scientific but techno-militaro-politico-diplomatic through and through, and which brings into play the doxa or incompetence even in its calculations. (Derrida, 1984: 24)

The final end is thus the ultimate simulation, the perfect media event … the absolute referent of everything that is, suspended before our eyes in writing, through texts. This, though, as Derrida writes, is the condition of all writing:

as soon as we no longer know very well who speaks or who writes [he writes], the text becomes apocalyptic. And if the dispatches always refer to other dispatches without decidable destination, the destination remaining to come, then isn’t this […] the structure of every scene of writing in general […]: wouldn’t the apocalyptic be a transcendental condition of all discourse, of all experience itself, of every mark or every trace? And the genre of writings called ‘apocalyptic’ in the strict sense, then, would be only an example, an exemplary revelation of this transcendental structure. In that case, if the apocalyptic reveals, it is first the revelation of the apocalypse, the self-presentation of the apocalyptic structure of language, of writing, of the experience of presence, either of the text or of the mark in general: that is, of the divisible dispatch for which there is no self-presentation nor assured destination. (Derrida, 1982: 87)

Writing is always threatening to arrive at an end; it is always, in this sense, apocalyptic. It is always in the act of answering the nuclear question. What counts in the weighing up of what kinds of writing matter, then, is not so much the putative differences within writing itself (it can’t be that) but who does the counting. Tough shit, in other words, if you happen to write like a postpolitical white boy - if what you write is up itself rather than outside itself.

Me? I’m a greenie, I’m a feminist, I’m a woman, and I’m black. Christ, I’m a fucking goddamn germ liberationist! All God’s creatures should be free. I’m also a nigger-baiting, bible-thumping, mother-fucking bastard. That’s just the kinda guy I am. I wear secondhand clothes and drink VB, like the rest of the hip crowd, and listen to a lot of Elvis records: sure signs that I’m a style Nazi, not an activist. You guessed it: I’m a Niallist. On the brink of the apocalypse, I preach the fetishization of a self-made king.

Inside narrative

I remember when I lived in the inner-Sydney suburb of Newtown in the late 1980s there was some graffiti that always caught my eye as I walked along the top of Erskineville Road to King Street and the shops, which I did virtually every day. It was just three words, but as much a part of Newtown for me as the cafés, the weirdness and the train station. The words were do not frolic, painted in black foot-high letters, all in lower case, on the back wall of a women’s clothing store, I think. But just that: do not frolic. I used to take friends there to show them the words, or tell them to go there themselves. And in all this time it’s never occurred to me to wonder about who wrote them or what they mean. Because what they mean is not only what they are, but where they are, and where I was then. As for who put them there, I can well imagine what they were wearing at the time and what they’d been doing: op shop clothes from King Street, drinking. That’s what everybody wore in Newtown and we all did a lot of the other. But apart from this very general description, which is more or less a pure fiction, I know nothing about their author or what he or she might have meant by the words. That’s probably why I’ve always like them, and also because I like the sound of the word ‘frolic’. In run-down come-alive Newtown, ‘frolic’ was a word that seemed bizarrely out of place and old-fashioned, a sardonic reminder that the grand old buildings of King Street stood now in decaying honour to a lively past, when whole families came to Newtown at weekends to visit the cineramas and amusement parlors and the vast indoor aquarium (you can still see the original façade of moulded fish and seashells above a secondhand furniture store, at the Chippendale end of King Street), and men came every day and at all hours of the night to visit the brothels. There used to be quite a lot of frolicking in Newtown back then, and so I always thought the admonition not to frolic, if that’s what it was, was wistfully ironic. And I always loved the fact that it appeared to have no context, even while it was steeped in a context of the everyday and the not so very long ago.

I’ve heard a rumour that David Malouf, who spends half his year writing in an out of the way village in Florence, Italy, returns to Newtown for the final draft which he finishes (according to the rumor) in a renovated four-storey mansion that used to belong to an ex-officer of the Parramatta Regiment, granted, as was then the custom, for a pittance on retirement from the military.

There is no “pure” Elvis. It’s just a myth to suppose that Elvis sold out to Colonel Tom and Hollywood, leaving his roots behind. What’s so bad about Hollywood, anyway? Why is what Elvis recorded for Sun more “authentic” than his recordings for RCA, or his movie soundtracks? Blame it on the hippies. As Greil Marcus writes: ‘At RCA, where the commercial horizons were much broader than they were down at Sun, Elvis worked with far more “artistic freedom” than he ever did with Sam Phillips.’ (Marcus, Tell it to the 1960s, because that’s when selling records became a dirty business. Everyone got so goddamn serious in the 60s (and the 90s were just the 60s upside down, if you lived in Fremantle), that commercial success came to represent creative loss of control. There were exceptions, of course, or blatant contradictions: like, it was OK for Dylan to go to number one with Like a Rolling Stone and still be hip, but all those dates that Elvis was playing in Vegas, man - that was very uncool. Of course, Dylan wrote Like a Rolling Stone from the heart and for himself; whereas Elvis was performing for the masses. Besides, the money Dylan made didn’t show: he still dressed like he didn’t care - in faded jeans and worn-out boots, his hair done up like a fright wig. Elvis, on the other hand, was going camp, thus committing the most unpardonable of 60s’ sins: he didn’t look like his audience any more. He wore stage clothes, not street clothes; and all those fake jewels and sequins could mean only one thing: he was faking his emotions, too. Like, all you had to do was listen:

Music: Elvis, An American Trilogy

This morning, while I was still writing this, I had a crisis in the shower. Just as I was about to step out, I couldn’t decide whether I’d remembered to wash my feet or not. Right away, I got paranoid. Should I postpone returning to the computer in order to make sure my feet are clean, thus running the risk of not finishing my paper in time for this volume’s deadline; or do I step out of the shower now and risk overpowering all I encounter with foot odor later on? In the end I decided to stay under the shower and wash myself all over again, being especially careful to wash my feet. That way only my prose would stink. Afterwards, my body purified, I went next door to my neighbor’s house to borrow a couple of Bob Marley records and purify my mind. But then I remembered that Bob Marley belonged to a religion (of sorts) that believes that menstruating women are unclean. So much for tribal purity. I told my neighbor that if he ever played a Bob Marley record again, I’d set fire to his wife’s hair with my Zippo and burn something blasphemous in the bellies of his children. Then I went home and played Elvis records for an hour, feeling really good about myself, and wrote a postcard to Rob:

Dear Rob,

Tell Mark he’s a bastard. What do you mean, ‘Graceland is a zoo’? You were expecting an opulent palace after the fashion of Versailles, perhaps? When was the last time you took a visit to the Western Suburbs? Maybe they don’t have mirrored ceilings, but they’ve got mirrors in more rooms than just the bathroom and more TVs in the house than you or me. Graceland city, mate. Poor white trash made good. Earth rapists. Environmental vandals, all. Elvis is their god - they just don’t know it. Why wouldn’t he be? The hippies killed him, which is what they want to do to them…

The rest is personal.

No, not the end. Not quite, not yet. There must be something more I can say about a man who’s sold more records than anyone else, made 33 Hollywood films, and during his lifetime was the highest paid performer in the history of Las Vegas. Everyone knows that the songs Elvis cut for Sam Phillips at Sun studios in 1954, with Scotty Moore playing guitar and Bill Black on upright bass, are rock’s most precious artifacts: because they’re its origin. The real thing, an absolute beginning. All you have to do is see Jim Jarmusch’s Mystery Train to find this out. But you might remember an early scene from that film, set inside Memphis Central station, where an old black man holding a cigar comes over to the Japanese couple who’ve just got off the train and asks for a light. The boy, pure rockabilly stylist, obliges with a flick of his Zippo. He and his girlfriend have come to Memphis on a pilgrimage, to visit the sacred sites of rock’s origin - especially Sun studios (or the Memphis Recording Service as it was known before 1952) where Elvis and Carl Perkins first sang in front of a microphone. It isn’t until the credits roll (or perhaps until long after), however, that we find out the old negro in the train station was Rufus Thomas, who’d been cutting discs with Sam Phillips at the Memphis Recording Service, and later at Sun studios, for quite awhile before Elvis or Carl Perkins showed up. Should we ask, then: how can rock have a beginning if that “beginning” isn’t over yet? For there to be a rockabilly “revival,” for instance, doesn’t rockabilly first of all have to have passed away?

So … no beginning: no post-mortem. No after words. I mean it. If you want to ask questions, you’re welcome to call me at home.

Just ask for Pete.

1968 revisited

Those of you who’ve seen Steve Martin’s Roxanne might recall a great scene at the beginning of the film in which Darryl Hannah, who’s completely naked at the time, locks herself out of her house one night. Briefly: Steve Martin, the local fire chief, agrees to break into her home and asks if meanwhile she could use a towel. Looking utterly surprised, Darryl Hannah says no. A few minutes later she asks him: where’s the towel? ‘You told me you didn’t want a towel,’ Steve Martin says. ‘I was being ironic,’ Darryl Hannah replies. ‘Oh … irony,’ Steve Martin says. ‘Oh yeah. We don’t do that anymore. There hasn’t been any irony around here since 1968.‘

Bibliography

Derrida, Jacques. ‘The Law of Genre’, trans. Avital Ronell, Critical Inquiry, vol. 7, (Autumn, 1980).

---. ‘Of an Apocalyptic Tone Recently Adopted in Philosophy’, Semeia, Vol. 23, (1982).

---. ‘No Apocalypse, Not Now: Full Speed Ahead, Seven Missiles, Seven Missives’, Diacritics, Vol. 14, No. 2, (1984).

Pynchon, Thomas. The Crying of Lot 49 (Picador: London, 1979).

Thwaites, Tony. ‘Miracles: Hot Air and Histories of the Improbable’ in Niall Lucy (ed) Postmodern Literary Theory: An Anthology (Blackwell: Oxford, 2000).

Marcus, Greil. Mystery Train: Images of America in Rock’n’Roll Music (E. P. Dutton: New York, 1976).

Wark, McKenzie. Virtual Geographies: Living With Global Media Events (Indiana University Press: Bloomington, 1994).

Cite this essay

Lucy, Niall. "The King and I: Elvis and the Post-Mortem or A Discontinuous Narrative in Several Media (On the Way to Hypertext)" Electronic Book Review, 9 May 2007, https://electronicbookreview.com/publications/the-king-and-i-elvis-and-the-post-mortem-or-a-discontinuous-narrative-in-several-media-on-the-way-to-hypertext/