The Visual Music Imaginary of 88 Constellations for Wittgenstein: Exploring Philosophical Concepts through Digital Rhetoric

88 Constellations for Wittgenstein (To be Played with the Left Hand) (2008) by Canadian artist David Clark is a web-based Flash creation that explores the life and works of Austrian-born philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein. In this paper, we show how rhetoric and digital technologies join to visually express philosophical concepts. The idea of “visual music” has been previously addressed in various fine arts such as literature, film, painting, sculpture, and music itself. We argue that in electronic literature it is possible to explore this concept by means of what we propose to call “gestural melodic manipulation”, which is the interplay of semiotic units (e.g. videos, sounds, images, linguistic texts) that the reader can add to the narrative by means of interaction and manipulation. In Clark’s e-lit work, “visual music” triggers the literary characteristics of the text by exposing different discourses and diverse thematic through intertextual and intermedial practices.

1. Introduction

“Uttering a word is like striking a note in the keyboard of imagination” -Ludwig Wittgenstein, Philosophical Investigations

The Canadian bilingual landscape of electronic literature is composed of multiple artists and creators whose works have become important first stones in shaping the country’s e-literary history mosaic. The continuous production of literary objects shows that as the field of e-lit constantly expands around the world, national literary frameworks begin to emerge in diverse digital creation latitudes. This chapter explores how David Clark’s net.art piece 88 Constellations for Wittgenstein (to be played with the Left Hand) (2008) stands as one of the digital torches of this on-going definition path within the Canadian landscape. We consider that Clark’s electronic literary work is a great example of Canadian digital poetics because (1) it proposes a labyrinth-like poetic of navigation based on a highly intellectual dialogism of media, (2) it shows the aesthetic advantages of mingling electronic literature, film, music, and philosophy; and lastly (3) it tests the aesthetical engagement of the reader by crossing click by click generic boundaries.

David Clark’s net.art works include various web-based projects of different natures and textualities. Among which we can find, A is for Apple (Clark 2002), a hypertextual linking and interactivity piece that interconnects the variety of associations surrounding a single object: “the apple” by knitting secret correspondences among Newton’s apple, Magritte’s apple, Adam’s apple, Apple Computers, the Big Apple, to name but a few. The work puts into question the relationship between our existence and our perception of the world, or as the narrative voice puts it, how “the tyranny of images” affects our perception of the world. Sign After the X (Clark 2010) is an interactive encyclopedia around the letter X that ingeniously allows the viewer to browse through symbolic associations, ideas, and mysteries attached to this letter: the X-Ray history, the X-men comic book, the X chromosome, the generation X, John Singer Sargent’s The Portrait of Madame X, among others. Lastly, 88 Constellations for Wittgenstein (to be played with the Left Hand) (Clark 2008) (hereafter 88C) is a web-based Flash creation that explores the life and works of Austrian-born philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein mingling philosophical concepts, secret logic, language games, and interconnected narrative stars. Each constellation is pictured as a possibility of thought, a labyrinth of myths, a rhetoric riddle, a musical score, or a new set of philosophical propositions. As we can observe, Clark’s net.art projects distinguish themselves because they spring and spin creation from two axes: (1) specific objects or ideas, and (2) facts and stories of our world. Such vivid, unifying, and defining elements produce scenarios of unexpected iconic associations, interactive storytelling, multimedia essays, and encyclopedic imagery, where the reader’s engagement with Clark’s works is driven by the dynamics of history, language, and knowledge.

In 88C, the idea of playing a musical instrument, in this case the piano, to achieve the literary, rhetoric, and artistic effects of the e-lit work brings back to us what Ryan suggests in her book Narrative Across Media, “What counts to us as a medium is a category that truly makes a difference about what stories can be evoked or told, how they are represented, why they are communicated, and how they are experienced” (2004, 18). Following Ryan, we argue that 88C is told through an interactive multimedia night sky where the leitmotifs of music, universe, and infinity join to represent the life and works of Austrian-born philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein. Further, 88C is a story represented through the lens of science, literature, film, music, and philosophy; it is communicated because it offers a new approach to philosophical thinking and metaphysical investigations using digital rhetoric practices; and, lastly, the constellations’ construction of meaning is experienced by interaction and manipulation where the paratextual message “to be played with the Left Hand” invites the reader to engage with the work by unraveling stories and playing language games.

As it is well-known digital technologies have brought certain characteristics to the digital texts such as hyperlinks and animation. According to Saemmer these elements are constitutive components of digital texts, and they shape specific rhetorical figures (2015, 15). The concept of rhetoric applied to digital texts should require sustained attention to the way rhetoric changes in and thanks to digital texts and how the digital (and technology) is molded by human expression about and through both the digital and the technology themselves. We are particularly interested in seeing how in Clark’s work the digital text uses/adapts/reinvents “canonical” rhetorical figures—verbally, visually, and aurally—to visually express philosophical concepts. We will focus on elements of the rhetorical canon in terms of their relation to their (re)production in a digital text. In this respect, Brooke highlights that “canons can help us understand new media, which add to our understanding of the canons as they have evolved with contemporary technologies. Neither rhetoric nor technology is left unchanged in their encounter” (2009, 201). Therefore, following Brooke, we will explore such encounter in the constellations taking into consideration the canons, digital rhetoric practices, and new media literary objects.

Over this theoretical basis, we argue that two metaphors bring together the representation of visual music in 88C: the dynamics between intertextuality and intermediality within the constellations and the gestural melodic manipulation of the secret of the “left hand.” By gestural melodic manipulation we understand “the action of the reader as an enunciation of gestures” (Bouchardon 2011, 39) that reveals the materiality and therefore the rhetoric of the text through musical sensations. By visual music1 we understand the visually expressed semiotic products triggered by the reader’s gestural melodic manipulation on the piano (computer) keyboard. Further, our intermedial research interest relies on the interrelations and iconic associations that can be found between the constellations’ various arts and media. Lastly, as the e-lit work has 88 points of departure, we have based our analyses on two specific constellations and their multiple non-linear interconnections: Ursa Minor 12 (Constellations) and Hydra 59 (The Limits of Language).

2. Ursa Minor (12): “The World is the Totality of Facts”

The uniqueness of Ursa Minor2 (hereafter, UMI) relies on the fact that there is no story within the constellation. However, UMI is precisely the beautiful presentation and representation of all the stories and imaginaries that construct 88C for it visually draws by means of a métaphore filée3 the way in which the stories can be read and navigated throughout the interactive sky. As we can read in the following passage, UMI’s description is constructed by means of statements, of facts. This means that the narrative voice removes itself from the enunciative act and the messages are presented as assertions of a fact, or as it is the case in UMI, as a set of postulations.

(1) That star there; that one as well; together, next to each other, one and the other, and another, and another. Let me get to the point. A point is a fact. A line connects two points. A line is a story that connects two facts. A story is a vector connecting facts together. These vectors make pictures; as above, as below or vice versa (UMI transcription, 88C).

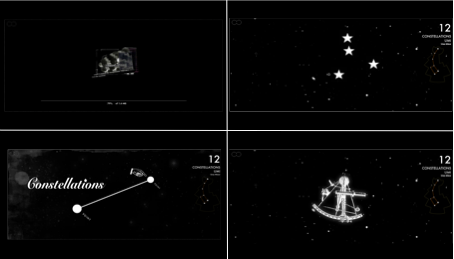

The deconstruction of the métaphore filée begins with the description of the digital arrangement of the constellation map, “That star there; that one as well; together, next to each other, one and the other, and another”, which verbally draws and visually emphasizes the title of UMI itself: Constellations. Thereafter, through persuasive animation and iconic association, the narrative voice addresses the reader and draws the linguistic and graphic point of departure of the work: “Let me get to the point. A point is a fact” (our emphasis). This is a graphic way to deconstruct 88C visual and spoken postulations: What is a point? What is a fact? What is a line? What is a story? What is a vector? What is a picture? And, more importantly, what is the relationship between them throughout the whole work? In an interactive sky where UMI is the graphic representation of vectors connected by stars (points/facts) even darkness tells a story about the universe. As Clark puts it, “It seemed strange to me that these constellations—so vividly depicted in old astronomy diagrams with elaborate pictures of mythical animals and gods—are pictures made from mere points, like an elaborate cosmic game of join-the-dots” (2015, 140). The idea behind UMI is to present the imaginative quality of the métaphore filée that builds up the sextant of 88C (“the chronotope of the sextant”). In other words, constellation 12 Ursa Minor (Constellations) stands as the navigating reference star of Clark’s digital work, where each point connects a fact and each line draws (clicks) the beginning or continuation of a story (see fig. 1). The architecture of the constellation map is an example of how rhetorical practices of arrangement create new connections, relationships, and stories in the digital environment. Therefore, if extrapolated to the context of 88C, Wittgenstein’s postulation, “The world is the totality of facts, not of things” (Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, 1.1) can be read as, “The world (universe) is the totality of stories”; and therefore, the totality (variety) of texts, and we would add, of modes and nodes of creative memory.

As one of the characteristics of reading and analyzing e-lit works is the possibility to (re)define, (re)evaluate, (re)locate, and (re)visit through multiple materialities such temporal and spatial concepts, it seems to us as if the digital arrangement of the constellation map were not only an allusion to the stars and stories that construct the 88 constellations within the digital work, but also an allusion to their aesthetic and rhetoric use of time and space. To put it differently, transformations of time concepts and spatial representations in the constellations allude to the possible chronotopic or non-chronotopic readings applied not only to the constellations themselves but also to the facts and stories of the world that knit together the imaginary of 88C. In the constellations, what we propose to call, “digital literary chronotopes” (e.g. “the chronotope of the sextant”) are constructed around an object or concept and emerge from the fusion between the historical time of the facts and stories of the world (story), the fictional time of the reader’s engagement, and the digital space of their creation.

2.1. Intertextual and Intermedial Stars

There are two ways in which intertextuality and intermediality are depicted in 88C, on the one hand, they can materialize as an allusion or quotation to specific literary references written by Wittgenstein or written for Wittgenstein: Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus (1961) (hereafter TLP), Notebooks 1914-1916 (1979), “A Lecture on Ethics” (1993), Philosophical Investigations (2009), Ludwig Wittgenstein, A memoir (Malcolm, 1962), and so on. On the other hand, given the 88 possibilities to explore 88C, they can materialize as intertextuality and intermediality of images or linguistic texts within the same constellations. It seems to us as if the intertextuality based on the TLP that flows through 88C creates its own elaborated intertextual aesthetics which highlights the co-relation between philosophy and intermedial practices. A good example is the re-appearance of images from different constellations in UMI (e.g. constellation 18 Cassiopeia (Cassiopeia) showing Cassiopeia’s vector (W), constellation 43 Ophiuchus4 (Vienna) showing the silhouette of the city of Vienna, constellation 8 Octans (Piano) showing the figure of a grand piano). This fact not only alludes to the interrelated imaginary and secret correspondences throughout the work but also to the transformations of time concepts and spatial representations in the constellations (“digital literary chronotopes”). That is, through intermedial travels the reader voyages from Greek mythology to Vienna’s cultural and intellectual history of the Twentieth Century; and from black and white political associations of the piano’s keyboard to the fascinating narrative darkness across the universe. These travels become points of narrative reference for the reader, interconnecting gateways of cultural imagination and visual memories. Such intertextual allusions not only establish a direct relation to the postulation, “The world is the totality of facts, not of things” (TLP, 1.1), that the narrative voice skillfully draws on the screenic surface, but also reaffirm Clark’s poetics of finding narrative art in the unexpected associations derived from the dynamics of logic, language, and knowledge that build up our world’s history.

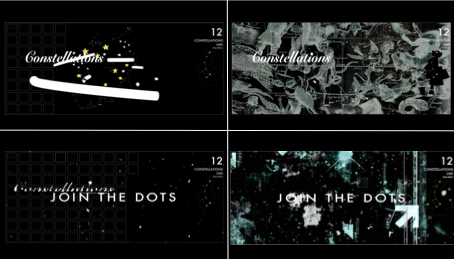

Further, the re-appearance of the constellations’ main wallpaper alludes to the introductory video of 88C where the repetition of the linguistic text and voice, “Join the Dots” makes a direct reference to the e-lit work’s interactive philosophy: to interlace the story of Ludwig Wittgenstein by “joining the dots together, making pictures in the sky, and connecting the model of our thinking to those drawings in the sky” (Introductory video, 88C). The intertextual repetitions of linguistic texts, images, and sounds through intermedial couplings create an allusion to previous artistic engagements the reader has experienced (played) while navigating the work. These engagements underline how intermediality serves as a strategy to depict visual and gestural memory. That is, they represent the visual music imaginary of the reader’s memory, a recollection that produces an intertextual/intermedial anamnesis effect through images and sensations already experienced by the reader; or as suggested by Clark, the feeling of experiencing a “narrative vertigo” while navigating the work, “a delusion of reference, where innocuous events and coincidences are seen as having heightened importance” (2015, 137–38). Hence, the act of randomly finding patterns and abstract renderings in the facts and stories of our world is the creative core of 88C for as readers we become mediators of the delivery of (visual) memory through interaction and artistic immersion.

From a different perspective, such anamnesis effects stand as examples of “aesthetics of re-enchantment” (Saemmer, 2009) because by remembering these images the reader experiences a process of re-enchantment via interaction which hosts an inner process of aesthetic identification of images and sensations previously felt in the embodied experience with the work. For instance, the visual and aural representation of “Join the Dots” gradually leaves traces not only on the surface of the work but also on the reader’s gestural memory where a piano key memorization process begins to unravel. We consider that these traces create examples of “animated sporulation,” understood as the multiplication of letters that make sense in an incongruous way (Saemmer, 2010, 175). That is, by generating a multi pop-up of the letter W within the reader’s encyclopedic imaginary, the appearance of iconic associations and secret logic attached to the letter W trigger the following visual interpretations from previous poetics of navigation: Vector: Cassiopeia (W or M): Ludwig Wittgenstein: Malcolm: Crown: World: WWI: Wittgenstein: Wien: Wit: Wiener Kreis, Margaret Wittgenstein, Malcolm: Crown: World: Twin Towers, WWI: World Wide Web.

As previously mentioned, intertextual and intermedial memory within the constellations establishes multiple iconic associations to Wittgenstein’s proposition, “The world is the totality of facts, not of things” (TLP, 1.1). In the first place, this linguistic text features the TLP at the beginning of constellation 04 Orion (Ludwig Wittgenstein) where it serves as a background to introduce Wittgenstein’s biography and philosophical works. Likewise, the proposition joins the stars of constellation 1 Aquarius (88), where it represents facts and stories of the world related to number 88 (e.g. two infinites ∞∞, 88 constellations, 88 piano keys, Chaplin, Hitler and Wittgenstein’s year of birth [1889], 88 searchlights placed as a tribute to the Twin Towers attack in New York, to name but a few associations). Further, it stands as the poetic background of constellation 46 Centaurus (Tractatus) to represent Wittgenstein’s logic and language masterpiece, the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus. Secondly, it is discussed and visually expressed in detail in constellation 52 Corvus (Facts not things) where through iconic associations and persuasive animation each letter “O” of the proposition’s linguistic text, “The wOrld is the tOtality Of facts, nOt Of things,” resembles the world spinning around. This animation shows an example of movement acting as an iconic sign where the rotation of the Earth represents the rotation and interconnection of the facts and stories of the world. Lastly, the proposition accentuates the different poetic twists that language generates in each constellation, as the narrative voices puts it, “It delineates the idea that we can only know the world through our ideas of it, as language disguises our thoughts” (Constellation 52, Facts not things, 88C). Clark’s poetics shows that Wittgenstein’s propositions can materialized into multiple textualities and associations, which proves that philosophical concepts trigger new modes of digital invention.

Moreover, these examples of time concepts and spatial representations in the constellations show how 88C weaves an intermedial memory through semiotic resources that spring from the artistic gaps of intermedial discourse. If we consider that memory among the constellations is constructed through different media (linguistic texts, images, sounds, videos); therefore, amongst such medial constellations, there are “intermedial bridges” made of multi-materiality bonds that can be interpreted from a variety of critical approaches depending on the intermedial practices they stand for. Intermedial practices within works of electronic literature have specific research objectives, in the case of 88C, we sustain that they join rhetoric and digital technologies to visually express philosophical concepts, such as logic, evidence, consciousness, reason, language, and infinity. Clark’s skillfully combination of Wittgenstein’s philosophy and visual representation challenges the screenic surface in a sort of philosophical digital rhetoric encounter where the complexity of Wittgenstein philosophy meets (tests) the possibilities of representation of electronic literature.

2.2. Visual Music and Piano Keys

The secret of the left hand is the painter’s brush in 88C’s construction of meaning as it becomes the interactive musical score of alternative imaginaries. It creates associations from Maurice Ravel’s “Piano concert for the left hand” (1929-1930) to Paul Wittgenstein’s multiple performances of piano compositions to be played with the left hand. By using the keyboard with the left hand (the former understood as the piano keys, and the latter understood as an homage to Wittgenstein’s brother Paul a concert pianist who lost his left hand during WWI), the reader can alter the constellation’s semiotic and temporal setting at any moment during the reading experience. After playing the piano with “the hand that is left, left behind in the digital age” (Constellation 63, Left Hand, 88C), the reader is left with the sensation of artistic inspiration and participation. For in such contexts, as proposed by Simanowski in Digital Art and Meaning, “we think much more directly through the body and feel the meaning of the work at hand” (2011, ix). The fact that a computer keyboard is associated to the creation of visual music on a piano keyboard highlights the metaphorical relationship between the interactive gesture (playing the piano keys), the media content that can be activated (unknown musical semiotic resources under the piano keys) and the activated media content (linguistic text, image, sound, and video propositions). By developing flexibility and suppleness in the hands of the reader, such metaphorical relationship confirms Clark’s intention to create a labyrinth-like poetic of navigation, where narrative passages, secret logic, iconic associations, encyclopedic imagery, and narrative vertigo are the main elements of rhetorical and philosophical creation.

Gestural melodic manipulation opens a vast of visual music imaginaries in 88C; for instance, in Ursa Minor the piano key W activates the images of a musical score overlapped with a city (most probably Vienna).5 This produces an intertextual/intermedial anamnesis effect as the images appear and disappear while the reader presses the piano key W provoking reminiscence and association of previous constellations on the reader’s visual memory. The reader remembers the previous associations to Vienna in 88C and in Wittgenstein’s life: the Vienna house in which the philosopher grew up, the Vienna Circle, the Viennese architecture, his memories in the Prater amusement park, to name but a few. These memories become intertextual stars that interconnect to constellation 43 Ophiuchus (Vienna) through the encyclopedic imagery of Johann Strauss’ Waltz “The Blue Danube”, that is, as the group of philosophers, theoreticians, composers, historical characters, and Viennese places appear by playing different piano keys on the screenic surface. The constellation becomes a cultural and historical orchestra hall full of political and artistic visual music memories (A: Sigmud Freud, O: Prater Park, N: Robert Musil, M: Theodore Herzl, C: Karl Proper, K: Blue Danube Waltz, G: Paul Wittgenstein, F: Vienna Circle, D: Ludwig Van Beethoven, H: Ludwig Wittgenstein, J: Karl Krauss, L: Otto Weininger, E: Aldof Hitler, I: Kundmanngasse House). These examples show that the significance of the dynamics of juxtaposition in the constellations is to create a process of association within the individual narrative worlds of the stars that places juxtaposition itself as a rhetorical process of invention.

On a different scenario, the piano key Y activates two things, the silhouette of a grand piano and the silhouette of the Haus Wittgenstein, a house the philosopher designed for his sister Margaret S. Wittgenstein in 1925.6 The images appear again and again by pressing the Y piano key. This is an example of visual music through the figure “interfacial involution” because the manipulation gesture is invariably followed by the same effect (Saemmer 2010, 170). In 88C “interfacial involution” represents intertextuality of memories or repetition of events. It is also an example of “aesthetics of re-enchantment” or “narrative vertigo” because the reader might have previously experienced constellation 44 Sagittarius (Kundmanngasse House), and the image of the Haus Wittgenstein simply brings back the encyclopedic imaginary surrounding the Haus: architects Adolf Loos and Paul Engelmann, modernist Viennese architecture, the city of Vienna, and Loos’ book Ornament and Crime (1908). Further, the title of the constellation itself, “Constellations” appears on the screen by pressing the piano key F or U. Both piano keys can be activated precisely when the narrative voice says, “Let me get to the point” or perhaps “Let me get to the next story.” The linguistic text, “Constellations” stays on the screenic surface but if the reader presses the piano key U or F more than one time, the title re-appears again and again. Interestingly, we have found that “interfacial involution” is used for the visual re-appearance of titles, subtitles, and prefaces throughout the e-lit work (see fig. 2).

Lastly, making visual music with sound and color as semiotic substances can be an example of a visually “busy” and “typographically” dense aesthetic referred by Engberg as “aesthetic of visual noise” (2010, 2). The author defines that the density of semiotic substances creates busy atmospheres and crowded screens, which can blur the sight and understanding of the reader. In UMI, squares multiply on the already “typographically” crowded screenic surface producing the repetition of the same sound mixed with yellow and white stars (see fig. 2). As the squares gradually occupy the screen they create an intermedial bridge to constellation 22 Hercules (Doubles), where through a series of iconic associations (double XX, double U (W), double ++, double —) and encyclopedic imagery (WTC Twin Towers’ attack on September 11, 2001, Sigmund Freud’s projection of double meaning, Alfred Hitchcock’s double motif in Psycho), the repetition of the sound and images of the squares is used to portray coincidence, science, and history. Constellation 72 Equuleus (Moon) also shows examples of visual music through “aesthetic of visual noise” (Engberg, 2010), in this occasion, different piano keys trigger encyclopedic imagery to create a Moon related-aesthetic technique, featuring “the chronotope of the Moon”: Apollo 11, the image of Neil Armstrong’s first steps on the Moon in 1969, a ladder made of multiple letters “H”, an allusion to Georges Méliès’ film produced in 1902, “Le Voyage dans la Lune”, Wittgenstein’s quotation, “I know that I have never been on the Moon” (On Certainty, 1969), among others. The visual and sonic techniques employed in certain constellations may create a sense of excess on the poetic surface of the work (see fig. 2); however, such poetic excess can also be read as an aesthetic technique and visual strategy to accentuate the multi-materiality of the work and to portray the intellectual density of the author’s writing.

3. Hydra (59): “The Limits of Language are the Limits of my World”

Signifying water snake and representing the largest of the 88 constellations in the sky, constellation Hydra 7(hereafter HYA) hosts a scenario of philosophy. A cafe, a couple talking about human existence, quotations by Ludwig Wittgenstein and Jacques Derrida swirled into a coffee cup, allusions to French film director Jean-Luc Godard, a universe of meaning squeezed into a dark void; these are the elements that construct the intertwined ideas that brightly compose the stars of HYA (The Limits of Language). Echoing constellation number 30 Draco (Sky), the reader experiences HYA through a sky full of philosophical questions, where the voices of Wittgenstein, Derrida, Godard, a mysterious woman, and the narrator, intellectually converse.

(2) We were in a cafe drinking coffee together and talking about philosophy. And I said, “Wittgenstein said, ‘The limits of language are the limits of my world’”. And she said, “Derrida said, ‘There is nothing outside of the text’”. And I said, “The end of language is the beginning of existence”, and she said, “Isn’t that just another concept?” and I said, “Does existence exist before we existed?” and she said, “No”. Then there was a pause. The cream in my hand was poised over the dark void of my coffee. And then I said, “Did you see that Godard film, the one with the coffee cup?” And she said, “Yes, where we see the milk folding into the dark expense of his coffee cup, and in that cup of coffee there is a whole universe of meaning”. What does he say? “The limits of language are the limits of my world, and by speaking I limit the world: that is Wittgenstein”. Yes, Wittgenstein also said “Our words would only express facts as a teacup would hold a teacup full of water even if I were to pour out a gallon over it”. And then she laughed. She laughed out loud and she said, “Laughter is the limits of language. We laugh when the absurdity of language becomes apparent, when it tricks us into believing in a thing called meaning” and I said, “We never arrived at fundamental propositions in the course of our investigations; we only get to the boundary of language that stops us from asking further questions” (HYA transcription, 88C).

The story opens through memory, a recollection of a conversation about philosophy the narrator had with a woman. The dialogue begins when the narrator himself quotes Wittgenstein for the first time, “And I said, Wittgenstein said, ‘The limits of language are the limits of my world’.” The quotation brings back the different semiotic systems that visually represent this literary reference throughout the digital work. In HYA the reference appears as a book page from the TLP; interestingly, these linguistic texts become for an instant the threaded wallpaper of the spoken narrative, however they quickly vanish turning themselves into a degraded memory. In constellation number 30 Draco (Sky), as two supernovas are triggered by the secret of the left hand, the limits of language are compared to the limitless possibilities of interpretation in the Sky, as the narrative voice puts it, “Where do our words end? What good are our words out there in space?” (Constellation 30, Sky, 88C). This accentuates the idea of boundless interpretation within the constellations’ interconnections given that it opens a field of philosophical concepts about the ever-expanding universe. Likewise, “The limits of language are the limits of my world” connects HYA to constellation 48, Norma (The World) where an image of the world appears and disappears at the rhythm of the words, “this is the world as I found it, this is the world, the whole wide world.” This shows an example of movement acting as an iconic sign where the coupling between the linguistic text and the animation gives the sensation of different moments and points of contact that expand the imaginary of the blinking eye: dark and bright, known and unknown, real and imaginary, form and matter, universe and language. The visual music of these examples highlights that the center of Wittgenstein’s statements is based on that which can be possibly explained by means of language and that which cannot. It highlights the connection between universe, language, imagination, reality, and the world; to put it differently, the (im)possibility to express by means of language, that which does (not) exist in the world, and the (im)possibility to express from time to time things about ourselves and things about our world.

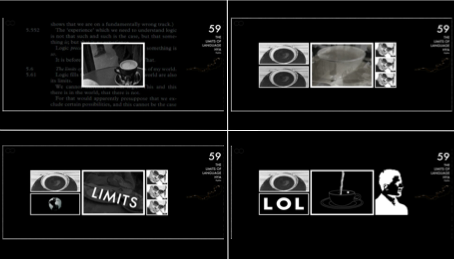

As each explorative star has its own unique features, the peculiarity of HYA is centered on the high philosophic and filmic tinges that skillfully turn the constellation into a thought-provoking twinkling passage. As the book page vanishes, the image of a hand swirling milk into a coffee cup appears as the narrative voice quotes Derrida within the woman’s speech, “And she said, ‘Derrida said, «There is nothing outside of the text»’.” The dark void becomes the universe where language, resembling matter, acquires different forms. This example of intertextuality underlines the endless contexts in discourse and artistic expression if we consider that every text is a text inside a text. The fact that these ideas are illustrated by Derrida’s renowned phrase, “il n’y a pas de hors-texte” (1967, 158), is an example of the maze of artistic relations in the constellations. As new associations begin to emerge amongst philosophy, film, and literature, the inclusion of a novel repertoire of aesthetic techniques to express different concepts intensifies. The benefit of thinking of electronic literature in terms of intermedial artistic relations consists of how the perception and interpretation of intermedia phenomena produces and reproduces new concepts such as philosophical questions. It is precisely the philosophical challenge to express such concepts in a digital scenario what suggests that this can be done through “digital literary chronotopes”, as it is the case with Derrida’s philosophical thoughts (“the chronotope of the café”) (see fig. 3). For example, in the plurality of the coffee cup, there is a play of texts, concepts, and traces; four different contexts are brought into play in order to create the context surrounding the conversation in the cafe: Wittgenstein’s Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, Wittgenstein’s “A Lecture on Ethics” (1965), Derrida’s _De la grammatologie (1967), and Godard’s Deux ou trois choses que je sais d’elle (1967). This shows that “digital literary chronotopes” create new intermedial travels and memories, and as we shall see, direct HYA’s narrative discourse towards different spatial and temporal possibilities of interpretation.

3.1. The Coffee Cup Soliloquy

We have outlined some of the possibilities of how anamnesis effects are constructed from objects: pianos, numbers, letters, cities, stars, sextants. In 88C, objects connect and interact in different space-times. In HYA a pause in the narrative discourse introduces a brief but evocative description of a coffee cup, “Then there was a pause. The cream in my hand was poised over the dark void of my coffee.” By describing the action of putting cream on his coffee, the narrator actives memory through the intertextuality and intermediality of images, which additionally creates an anamnesis effect through the iconic associations of a coffee cup. The recollection of a specific scene in Godard’s Film, Deux ou trois choses que je sais d’elle (“Two or three things that I know about her”) is evoked through the plurality of the coffee cup. This effect is an example of what Saemmer (2010, 177) calls “kinetic allegory” given that Godard’s film is represented through the animated image of “another thought”, and in this case, that other thought (the double representation of Godard’s original coffee cup image), “incites the reader to interpret a ‘story’ that the content of words alone does not tell”; in HYA such “content of words” refers specifically to the alternative imaginaries of the spoken narrative.

The coffee cup scene stands as a journey within the film itself, a detachment from reality, and a door to memory, “And then I said, ‘Did you see that Godard film, the one with the coffee cup?’ And she said, ‘Yes, where we see the milk folding into the dark expense of his coffee cup, and in that cup of coffee there is a whole universe of meaning’.” It seems to us as if the narrator were asking straightforwardly to the reader: have you seen that Godard film? do you remember that coffee cup? This action can be read as an invitation to recollect coffee cup images in our (visual) memory not only in 88C but also throughout our fine arts encyclopedia, which underlines the idea of objects triggering an associative recognition memory on the readers (see fig. 3). In a way, the simplicity and complexity of the words that swirl poetically in the coffee cup become the visual motif of the conversation. That is, by combining philosophical questions and filmic techniques (image-emotion-identification), new artistic layers are added not only to the conversation but also to the digital work in its totality. There is a dialogue between arts, as Clark merges film and philosophy to submerge the reader into the ∞∞ possibilities of interpretation within the universe swirling into the dark expense of a coffee cup.

The narrative experiences of 88C occasionally make the reader feel as if s/he were experiencing an interactive cinema. The bridge to Constellation 83 Sextants (2 or 3 things I know about her) is constructed of intermedial memories from HYA: Godard’s silhouette, Marina Vlady’s scene shots from the film, the coffee cup’s graphic and original image, and above all, Wittgenstein’s poetically referred quotation, “As the cream swirls around in the deep black abyss of the coffee a voice: ‘The limits of my language are the limits of my world and by speaking I limit the world’.” If we were to consider cinema in terms of intertextuality and intermediality, it is worth mentioning that on this specific scene of “Two or three things that I know about her”, the director inserts in the coffee cup soliloquy, literary references from Wittgenstein’s TLP. In other words, there is an intertextuality mirror effect that leads to a reverse process of expression since the same literary reference quoted twice by the homodiegetic narrator in HYA is expressed by the voice-over (Godard himself) when narrating the coffee cup scene in the film.

“Where do we start? But start what? God created the heavens and the earth of course, but this is a little easy to say. We should say it better: we can say that the limits of language are the limits of the world, that the limits of my language are those of my world and by speaking I limit the world, I finish it. And one inevitable and mysterious day, death will come and abolish this limit, and that there won’t be neither questions nor answers, all will be blurred. But if by any change things become clear again, it may only be with the appearance of consciousness, then everything will follow from there.” (Godard).8 (our emphasis).

In constellation 83 Sextants (2 or 3 things I know about her), such intertextual and intermedial effects show the creative fragmented structure of certain electronic literary works. For instance, the idea to encompass within the constellations’ aesthetic realms, bits and pieces of other disciplines such as film and science to experience an interactive narrative from multiple perspectives. In Sextants, the intermedial travels go from allusions to NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center (a research center that studies the Earth, the sun, the solar system and the universe, which was built in memory of physicist Dr. Robert Hutchings Goddard), to Marina Vlady’s scene shots and glimpses of the city of Paris in “Two or three things that I know about her.” Resembling the representation of Hydra’s twisting snake in the sky, the reader is caught in the twists of language that revolve within the constellations imaginaries: Godard? Goddard? God? Art? The process of “deconstructing” HYA shows that the voices of Wittgenstein, Derrida, Godard, the woman, and the narrator, not only depict a high degree of reserve process of expression but also introduce the plurality of contexts that the “(digital) text as world” and the “(digital) world as text” offer to the reader. Such reverse process of expression is an example of how certain filmic figures turn into possible examples of cinematic electronic literature, which underlines electronic literature’s heterogeneous nature and reliance on other potential modes of expression. On the other hand, this suggests that once in the digital scenario such “borrowings” experience new cycles of aesthetic appreciation due to their (re)contextualization through intermedial practices.

3.2. Philosophical Riddles

In 88C, philosophy tests the possibilities of representation in a digital scenario where constellations become intriguing puzzles occasionally represented by philosophical and rhetorical riddles, “Is it a W or is it an M? A chair or a crown?” (Constellation 12, Cassiopeia, 88C), “88 constellations, 88 piano keys, two fat ladies, or two upright infinities?” (Constellation 1, Eighty-eight, 88C), “Laughing Out Loud or the Limits of Language?” (Constellation 59, Hydra, 88C). The riddle is a task, a wordplay, a chiaroscuro meaning, an interplay of spaces. Through our poetic navigation of 88C the challenge has been to disclose the meaning of Clark’s philosophical riddle-like creativity, from the riddles of the universe to the riddles of the deep black abyss of a coffee cup. In Cassiopeia, for example, the riddle is constructed through a visual exaggeration producing the effect of what we propose to call “animated hyperbole”. This effect is formed when the rotating letters W and M, and the images of a chair and a crown appear on the screen coupled with the audio, “Is it a W or is it an M? A chair or a crown?” The mingling of modes evoking the rotating images of M, W, chair, and crown create a rhetorical riddle constructed of an animated hyperbole that produces fantastic associations and visual puns among Greek mythology, the narrative universe, and the letters M and W.

In HYA, the closing riddle in the coffee cup soliloquy emerges when the narrator and the woman conclude that if there is a limit to language then it is laughter. That is, when the limits of linguistic expression are reached, laughter comes into being to overexpress that which cannot be expressed by words, “Laughter is the limits of language. We laugh when the absurdity of language becomes apparent, when it tricks us into believing in a thing called meaning.” Laughter becomes a mysterious dynamic sound that can either signify nothing or signify it all. In this sense, laughter is a release from language and a reaction to language. As Clark puts it, “One of the themes in my piece, for example, is how Wittgenstein’s work on logic and language can now be understood in the context of the digital age” (2015, 141–42). In HYA logic and language are combined with animation to express the linguistic text “LOL” when the narrative voice says, “she laughed out loud.” Thus, one possible meaning is that “LOL” can either signify Laughing Out Loud or Limits of Language. This clearly accentuates the creation of visual puns through iconic movements, as a gyratory linguistic text showing word by word: Limits of Language and an image of the world rotating around its own axis are simultaneously seen on the screen (see fig. 3.)

At this point, the reader realizes that the narrator’s argument centers on the idea that words cannot capture it all, nor explained it all; they cannot critically nor linguistically apprehend the total visual imagery of the world, words are an attempt to solve the riddles of our ever-expanding (linguistic) universe, as pointed out by the narrative voice, “We never arrived at fundamental propositions in the course of our investigations, we only get to the boundary of language that stops us from asking further questions” (Constellation 59, Hydra, 88C). Following this stream of thought, perhaps such concepts as logic, language and laughter have found in Hydra’s narrative discourse not only the space to exploit different modes of representation but also the space to test philosophical systems of presentation in our conception of the digital environment.

4. Conclusion

The poetic practice behind 88 Constellations for Wittgenstein (to be played with the Left Hand) is a metaphysical reflection that joins together new possibilities to grasp and reformulate Wittgenstein’s philosophical concepts through digital rhetoric and intermedial practices. It seems to us that the degree of integration between digital rhetoric and philosophy maximizes its complexity when digital rhetoric figures are formed, since to form such figures the philosophical concepts ought to acquire specific iconic traits within the poetic frame of the work. Such iconicity traits skillfully and gradually knit a poetics of juxtaposition in the visual music imaginaries of the work. This enables the reader to confront and interpret secret logic, unexpected iconic associations, encyclopedic imagery, and digital literary chronotopes through gestural melodic manipulation. The poetic density of Clark’s work stems from the interconnections among electronic literature, film, music, and philosophy but the poetic enjoyment of Clark’s work lies on the challenge to deconstruct logic and language games in the constellations’ unexpected intertextual and intermedial interconnections. In such poetics of juxtaposition associative memory plays an important role when deciphering meaning. To put it differently, philosophical concepts are expressed through a poetics of memory where important intertextual and intermedial anamnesis effects craft visual motifs and rhetorical riddles in the constellations’ imaginative atmosphere. The effect of Clark’s poetics of juxtaposition on the construction of Canada’s electronic literature bilingual landscape sets the path to uncover and locate new intellectual traditions that begin to emerge within varied national literary frameworks of the e-lit world.

The authors would like to thank Canadian artist David Clark for the use of images and the wonderful conversations.

References

Bouchardon, Serge. 2011. “Des Figures de Manipulation Dans La Création Numérique.” Protée 39 (1): 37–46. DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/1006725ar

Brooke, Collin Gifford. 2009. Lingua Fracta: Toward a Rhetoric of New Media. NJ: Hampton Press.

Clark, David. 2002. A Is for Apple. https://dclark643f.myportfolio.com/a-is-for-apple.

———. 2008. 88 Constellations for Wittgenstein (to Be Played with the Left Hand). http://collection.eliterature.org/2/works/clark_wittgenstein.html.

———. 2010. Sign After the X. https://dclark643f.myportfolio.com/sign-after-the-x.

———. 2015. “Pictures in the Stars: 88 Constellations for Wittgenstein and the Online ‘Biography.’” Biography University of Hawai’i Press 38 (2): 290–96. https://doi.org/10.1353/bio.2015.0022.

Derrida, Jacques. 1967. De La Grammatologie. Paris: Éditions de Minuit.

Engberg, Maria. 2010. “Aesthetics of Visual Noise in Digital Literary Arts.” Edited by Raine Koskimaa and Markku Eskelinen. University of Jyväskylä, Cybertext Yearbook 2010. http://cybertext.hum.jyu.fi/index.php?browsebook=7.

Godard, Jean-Luc. 1967. Deux ou trois choses que je sais d’elle. France.

Grimal, Pierre. 1985. The Dictionary of Classical Mythology. Translated by A. R. Maxwell-Hyslop. Oxford, New York: Blackwell.

Malcolm, Norman. 1962. L. Wittgenstein: A Memoir. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Méliès, Georges. 1902. Le Voyage Dans La Lune (A Trip to the Moon). Star Films.

Ricalens-Pourchot, Nicole. 2003. Dictionnaire Des Figures de Style. Paris: Armand Colin.

Richter, Duncan. 2014. Historical Dictionary of Wittgenstein’s Philosophy. 2nd ed. Historical Dictionaries of Religions, Philosophies, and Movements 54. Lanham, Boulder, New York, Toronto, Plymounth, UK: Rowman & Littlefield.

Ryan, Marie-Laure, ed. 2004. Narrative Across Media: The Languages of Storytelling. Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press.

Saemmer, Alexandra. 2009. “Ephemeral Passages—La Série Des U and Passage by Philippe Bootz. A Close Reading.” Dichtung-Digital, no. 39. http://www.dichtung-digital.org/2009/Saemmer/index.htm.

———. 2010. “Digital Literature —A Question of Style.” In Reading Moving Letters: Digital Literature in Research and Teaching, edited by Roberto Simanowski, Jörgen Schäfer, and Peter Gendolla, 163–82. Media Upheavals 40. Bielefeld: transcript Verlag.

———. 2015. Rhétorique Du Texte Numérique: Figures de La Lecture, Anticipations de Pratiques. Villeurbanne Cedex: Université de Lyon Presses de l’Enssib.

Simanowski, Roberto. 2011. Digital Art and Meaning: Reading Kinetic Poetry, Text Machines, Mapping Art, and Interactive Installations. Minneapolis, London: University of Minnesota Press.

Wittgenstein, Ludwig. 1961. Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus. Edited by D.F. Pears and B.F. McGuinness. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

———. 1969. On Certainty. Edited by G.E.M. Anscombe and G.H. von Wright. Translated by G.E.M. Anscombe and Denis Paul. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

———. 1979. Notebooks 1914–1916. Edited by G.E.M. Anscombe and G.H. von Wright. Translated by G.E.M. Anscombe. 2nd ed. Chicago, Oxford: The University of Chicago Press.

———. 1993. “A Lecture on Ethics.” In Ludwig Wittgenstein: Philosophical Occasions 1912–1951, edited by J. Klagge and A. Nordmann, 37–44. Indianapolis and Cambridge: Hackett Publishing Company.

———. 2009. Philosophical Investigations. Translated by G.E.M. Anscombe and Joachim Schulte. Chichester, West Sussex/Malden, MA: Wiley Blackwell.

Footnotes

-

We are aware that the concept of “visual music” is used in other disciplines and has been addressed by various authors and artists, such as, German American Filmmaker Oskar Fischinger (1900-1967). ↩

-

In Greek mythology Ursa Minor is often associated with Arcas, son of Zeus and Callisto, nymph of the hunt and companion of Artemis. When Arcas was growing up, one day while hunting, he met his mother in the shape of a bear and chased her. As he followed her, he made his way into the sacred precinct. The invasion of the precinct was punishable by death, but Zeus had pity on them both and saved their lives by changing them into the constellation Ursa and its guardian, Arcturus (Grimal 1985, 51). ↩

-

Filer la métaphore, c’est la développer longuement et progressivement (Le Petit Robert). On appelle donc métaphore filée, une construction cohérente où l’image se prolonge de façon prévue ou imprévue (Ricalens-Pourchot 2003, 83–84). To extend the metaphor is to develop it long and gradually (Le Petit Robert). An extended metaphor is therefore a coherent construction in which the image is extended in a planned or unexpected way. ↩

-

Ophiuchus, Latin: “Serpent Bearer.” ↩

-

Vienna. Wittgenstein grew up in Vienna at a time when the city was perhaps at its most fertile culturally, in a house that was one of the centers of this cultural life. This was the Vienna of Karl Kraus, Adolf Loos, Arnold Schonberg, Fritz Mauthner, Robert Musil, and Oskar Kokoschka. The wealthy Wittgenstein family patronized some of these figures and took an interest in all the arts, especially music. This rich cultural background clearly influenced Wittgenstein’s thinking about culture and language, although exactly how is hard to say with both precision and confidence (Richter 2014, 230). ↩

-

Architecture. Wittgenstein’s interest in architecture was both directly practical and more theoretical. With Paul Engelmann, he designed a house for his sister Gretl, but he also reflected on the nature of architecture in his notebooks and in his lectures on aesthetics. In Culture and Value Wittgenstein says that “Working in philosophy ―like work in architecture in many respects― is really more a working on oneself” (16e). Work in architecture is also like work in philosophy, which Wittgenstein conceives of as grammatical investigation, because architecture is like Language (Richter 2014, 27). ↩

-

Hydra. In Greek legend, the offspring of Typhon and Echidna (according to Hesiod’s Theogony), a gigantic monster with nine heads (the number varies), the center one immortal. The monster’s haunt was the marshes of Lerna near Argos. The destruction of Hydra was one of the 12 Labours of Heracles, which he accomplished with the assistance of Iolaus. 26. Encyclopædia Britannica, http://global.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/278114/Hydra. ↩

-

“Où commence, _mais où commence _quoi ? _Dieu créa les cieux et la terre bien sûr, _mais c’est un _peu lâche et facile. _On _doit _pouvoir _dire mieux _: dire que les limites du _langage _sont celles du monde, que les limites de _mon _langage _sont celles de mon monde, et _qu’en parlant je limite le monde, je le termine. Et que la mort un _jour logique et _mystérieux _viendra _abolir cette limite, et _qu’il n’y aura ni question ni réponse, _tout _sera flou. Mais si par hasard les _choses _redeviennent nettes, ce _ne _peut _être _qu’avec l’apparition de la conscience, _ensuite _tout _s’enchaîne.” ↩

Cite this article

Meza, Nohelia and Giovanna di Rosario. "The Visual Music Imaginary of 88 Constellations for Wittgenstein: Exploring Philosophical Concepts through Digital Rhetoric" Electronic Book Review, 7 February 2021, https://doi.org/10.7273/44y2-5x03