Toward a Particulate Politics: Visibility and Scale in a Time of Slow Violence

Smaller than anything the human eye can see, yet not so small as the elementary waves and dark matter known to modern science: the particle is an appropriate figure for our present, intermedial ¨shuttling between entities at different scales.¨

Introduction: Scaling the Particle

The particle occupies a special scalar niche in human semiotics: it is large enough to bear meaning, but too small to experience with the unaided senses. Nothing that the unmediated human eye can discern is properly referred to as “particulate.” The smallest unit of sand, that prototypically minuscule object, is a “grain,” not yet a particle. Conversely, objects upon which we have no purchase, that we cannot isolate, such as elementary waves and dark matter, are not yet particles. The particle is defined, if at all, by scale on one side and difference on the other. The particle is thus a function, a dual cut: anything smaller seems to us to lack solidity or agency; anything larger tends to be marked as a directly manipulable object in our umwelt. It is this slippery status of the particle that gives it its transitive character, its semiotic capacity to bridge the visible and invisible worlds, and its ability to cross scalar thresholds. Alone, particles are invisible and undetectable by ordinary means, but in aggregate they alter the characteristics of their substrate, whether as “air quality” in the atmosphere or as radiation levels in the soil. The particle is a mediator, shuttling between entities at different scales, on one hand diffusing through a region or even the globe, and on the other concentrating in particular bodies, contaminating or killing them. As soon as particulates are enrolled in human control regimes, such as neoliberalism, that produce, distribute, concentrate, or contain them, a particulate politics emerges. The two chief dynamics of particulate politics are scale and visibility.

In this essay I explore some of the interrelationships between neoliberal control regimes and the scalar dynamics of particles. Neoliberalism encompasses and enrolls many scales (the individual, the nation, the economic zone, the globe), and obtains its efficacy by privileging certain scales, rendering others invisible, and engineering strategic linkages between them. The individual and the globe become focal points in the neoliberal narrative, while the scale of the community is elided entirely. As David Harvey notes, neoliberalism “holds that the social good will be maximized by maximizing the reach and frequency of market transactions” as a fundamental axiom, even an ethic (Harvey 3). Thus neoliberalism privileges not only particular scales, but scaling itself. A market ethic implies and requires not only a continual scaling up of the absolute size of markets, but also the saturation of exchanges within these spatial boundaries with the mediating dynamics of the market. That is, local exchange (including traditionally non-economic exchange such as water or nutrient access) is increasingly enrolled in a global market logic. Every expansion of the market also re-scales the scope, inputs, and outputs of the local transaction, as well as local production. Successful products must rapidly scale up to saturate the market, generating growth unthinkable in mono-scalar exchange (i.e., exchange restricted to only a local market). At the same time, neoliberalism must contain the byproducts of such scaling processes, including waste and contaminants of many flavors, from greenhouse gases to contaminated groundwater and the acidification of the oceans. While industrial capital was content to linearly scale up the entire field of production and consumption, neoliberal capital requires and enables fine, differential control over particular scales and directions; that is, control over what diffuses, what concentrates, what explodes or contracts, what circulates, and what is rendered invisible. Particulate dynamics are particularly useful to neoliberal capital insofar as they enable this fine control. Certain particles are manipulated to expand, while others are made to concentrate at localities out of sight. Maintaining particulates in a diffuse state, below the threshold of general visibility, is not merely a technical exercise, but also a medial one. This is partly because such fine technical control is impossible, and particles must be made to disappear by other than merely technical means, but also partly because, as I have noted, the particle is already semiotically charged: it is always on the threshold of becoming invisible or becoming visible to codification within medial circuits.

In taking up the question of the particulate, I aim to link both punctuated and ongoing environmental disaster to a scalar politics of visibility. As Rob Nixon has influentially argued, many or most environmental disasters do not register in human consciousness as events because they unfold over long periods of time and in diffuse spaces, and are thus “spectacle deficient” (Nixon 47). This “slow violence” lacks non-catastrophic signifiers, prompting Nixon to ask, “how can we convert into image and narrative the disasters that are slow moving and long in the making, disasters that are anonymous and that star nobody, disasters that are attritional and of indifferent interest to the sensation-driven technologies of our image-world? (3). At issue is how non-familiar scales can become signified at all, a question that can only be adequately answered by turning to natural (particulate) media whose dynamics are captured and exploited by neoliberal capital, but which at the same time always exceed and escape the logics of control. While the acknowledgement of slow violence implies a much larger medial project of rendering visible the temporally and spatially large scale of environmental disaster, I focus here on the special medial role that the particle plays in both doling out slow violence and in strategies of visibility employed by both neoliberal and resistance discourse in this struggle over the semiotics of scale.

In what follows I discuss two moments or movements that track the particulate as scalar mediator. The first is the catastrophic nuclear meltdown at Fukushima Daiichi in May of 2011. This event exemplifies the dynamic of containment that marks the global neoliberal milieu and its encounter with the radically trans-scalar, in the form of radioactive particles that quickly jump scales and evade detection even as they mediate relationships between control regimes, food supplies, and elemental mediums. My second example is the discourse of chemtrail conspiracy theory, which produces a narrative alleging the existence of a secret, global geoengineering scheme promulgated by anonymous scientists and technocrats. I argue that chemtrail media resignifies the atmosphere as a medium for the programmatic dispersal of toxic particulates and thereby moves from specific tactics of disaster response to larger-scale strategies of re-signification that rewrite the environmental (and elemental) semiotics of scale, enabling a toxic cartography that, while worlds away from rationalist academic discourse, strongly rejects the scalar elisions of neoliberalism.

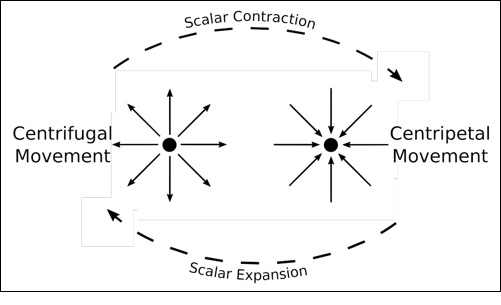

What unites these examples of the human and the post-natural squaring off over the role of the particulate in scalar mediation is a particular rhythm or cycle: first a centrifugal movement or dispersal outward, into the environment, then a centripetal movement or concentration inward, to particular sites or bodies. These movements flow into each other in a continual cycle, but with a difference: each successive movement produces a new assemblage at a new scale. For example, an industrial plant releases certain pollutants into the atmosphere. The plant is a pointal source of production, but this centrifugal release rapidly expands the scale of the contamination through airborne particulates. Those particulates gradually settle into soil and streams, and then accumulate in certain organisms. This centripetal movement once again shifts the scale of concern, now to individual bodies. Taken as an abstract diagram, this cycle of scalar shifts describes the movement of particles in an environment, but also more and less “tangible” particulate flows, such as those of capital, affect, and energy. In this example, the toxified bodies become objects of concern to local or national governments, enrolled as subjects of legislation or environmental remediation. But as they scale to the national level, they become part of the same structure of governmentality that stabilized the market and thereby brought the original factory into being. Each successive centripetal or centrifugal movement shifts dynamics from one scale to another, but also produces its complementary movement, like lungs inhaling and exhaling. I therefore refer to this diagram of scalar mediation as eco-scalar breathing (Figure 1).

The utility of this scalar model is that it can account for the entanglement of very different orders of being—particulate concentrations, legislative actions, discursive structures, and distributed affect, etc.—which nonetheless interact and fuel each other precisely through these choreographed movements. As the following examples will illustrate, eco-scalar breathing is a post-natural form of mediation that fundamentally incorporates anthropogenic dynamics (centripetal and centrifugal) and structures (hierarchies, medial infrastructures, populations) while remaining external to human intentionality. In its alterity, it is both “natural” in the sense of elemental, and also unnatural in its incorporation of technological drivers. Eco-scalar breathing thus poses a challenge and a promise: it asks us to engage with a form of mediation more-than-human in its scalar transformations and techno-social-elemental mutations. Many of eco-scalar breathings’ manifestations appear to us as violently perturbing from an ecological standpoint precisely because these domain shifts are so difficult to track. If we can gain some purchase on the scalar shifts enacted by particulate politics, however, we may dramatically increase our chances of tracking the entangled dynamics of neoliberal ideology, nonhuman media, ubiquitous technological control, and global climate change.

Neoliberalism and Particulate Politics: Fukushima Daiichi

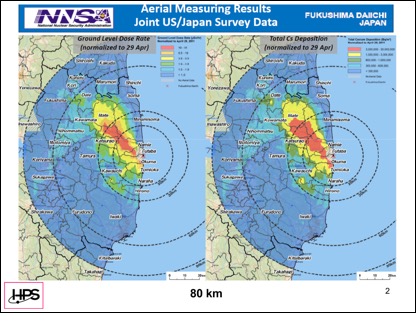

Tectonic mediation: The Pacific Plate shifts westward, crushing against the edge of the North American Plate (which “wraps around” the Pacific Plate, stretching all the way to Japan). Sometimes this longue duree collision forces one edge of the former under the latter (“subduction”), generating a massive earthquake. When this occurred on March 11, 2011, the resulting magnitude 9.0 earthquake shifted the entire planet’s axis by several inches (Lochbaum, Lyman, and Stranahan 3). Large scale forces indeed, rippling outward. What happens when they enter their centripetal phase? In this case, they triggered a massive tsunami that, along with the earthquake, killed almost 19,000 people in Japan. But the centripetal movement continued to concentrate these forces, smashing through a coastal facility in Fukushima Prefecture, flooding its buildings, and cutting off all power to the site. The site was a nuclear power station, of course, which perversely cannot maintain its integrity without external power. Three reactor meltdowns resulted, dispersing radioactive nuclides into the atmosphere (Figure 2).

This centrifugal movement of radioactive particles is not, of course, the scalar equivalent of the tsunami’s centripetal concentration in reverse. The first movement concentrated tectonic energy into a pointal site and transferred it into the medium of water, where it encountered human infrastructure. The subsequent centrifugal movement released a different storehouse of energy, itself the product of a global technoscientific regime of technical, energetic, and ideological flows concentrated on the Japanese nation by a political climate favoring energy independence and highly technical solutions to basic problems, along with an increasing push toward militarization and the exigencies of an historical alliance with the U.S., where it is pressed to become an active, militarized ally. This is to say that the history that produced the concentration of fissile material at Fukushima Daiichi is separate from the history that produced the 3/11 tsunami, but they are articulated together through eco-scalar breathing by virtue of their relative, inverse movements coming into alignment and sharing mutual dependencies—aquatic-terrestrial interface, for example.

Nuclear power generation relies upon a particularly tightly coupled process of eco-scalar breathing. Enormous resources and forces are brought to bear upon a tiny concentration point to kindle a self-sustaining fission reaction at the molecular scale, which endothermically radiates outward with massive force. To direct that force, it must be contained, and the nuclear reactor is designed to perform exactly this containment, directing energy through the medium of water into steam to power turbines, from whence high-voltage infrastructure enables a radiating network of electricity available for human consumption. Each successive movement effects a jump of scale, which must, according to the dictates of capital and technoscience, be fully controlled. Technoscience in its capitalist form is scalar control, or more precisely, the controlling of the means of scaling at critical transition points in eco-scalar breathing. The aim and ordinary result of this regime of scalar control is a post-natural, trans-scalar environment or ecosystem that serves capital, which uses its circuits for its own expansion and accumulation according to the same diagram.

This scalar control regime is part technical and part discursive. Nuclear fuel, at various stages of enrichment and in “spent” form, cannot truly be contained, as its potential energy exceeds the scale of the forces brought to bear in its containment. For decades, spent fuel was simply placed in metal or concrete drums and dumped into the ocean, counterposing the elemental media of water against the scale of the fissile particulate. Eiichiro Ochiai argues that “the purpose was to eventually disperse and dilute the radioactivity, rather than contain it. This had been practiced by most of the countries that operated nuclear power plants, until it was banned by an international treaty in 1993” (Ochiai 50). Dumping nuclear waste into the ocean disperses its radioactive particles in centrifugal fashion, allowing them to escape containment, but also rendering them below the threshold of visibility. Containment, by contrast, is centripetal, circumscribing the movement of particles into an ever more concentrated form. This distinction is a scalar one: radiation containment and extremely widespread dispersal provide a similar service to capital, but occupy diametrically opposed scalar vectors. Which is viable depends upon the conjoined forces in other domains with which each vector aligns. Particulate dispersal reduces intensity, increasing the scale of an event but thereby rendering it under the threshold of visibility, aiming at a statistical mean equivalent to strategies of population management and regulation. Containment, as the other side of the diagram of eco-scalar breathing, preserves intensity but isolates it from the population, managing its visibility as a singularity that can be veiled.

The moment of disaster, as nonlinear event, takes the form of abrupt change from one state, one scale, to another. As I narrated above, Fukushima as event marks the sudden reversal of forces from concentration to dispersal, from dispersal to concentration. Such evental scale changes are highly visible, at least momentarily. Fukushima was, of course, front page news. As such, it disrupts the standard rhythms of eco-scalar breathing that are managed by neoliberal capital and, for those who know where to look, even trains a magnifying glass on those standard forms of scalar management. In Japan’s case, Fukushima revealed a particulate politics predicated upon privatization and containment, which took the form of tightly coupled interactions and aligned goals of the Japanese government and private industry. Rather than regulating (in the sense of overseeing and restricting) the nuclear industry, the Japanese government (in the form of its NISA agency) had given carte blanche to the utility companies it was supposed to oversee, allowing them to perform their own safety inspections, write their own safety reports, and make their own regulatory rules. This included especially TEPCO, owner of the Fukushima Daiichi facility (Lochbaum, Lyman, and Stranahan 49). TEPCO routinely falsified all safety reports, and even when caught in 2002 and 2007, suffered only public relations setbacks (as this key knowledge of corruption escaped its containment and dispersed to the public), not restrictions nor punishment from the government. The tight, interdependent relationship between the government, the nuclear power industry, and other companies that invest in and supply nuclear power plants is commonly referred to in Japan as the “nuclear village.”

The government, both before and after the Fukushima meltdowns, sees its role in the nuclear energy sector as a promoter, a mediator between industry and public opinion. Just as it had arbitrarily decided (without any scientific evidence) that earthquakes in the area couldn’t exceed magnitude 8.0 and sought to sell nuclear energy to the populace as a safe and clean energy source, so now, under right-wing prime minister Shinzō Abe, the government utilized the disaster not as a call for clean energy (as Japanese citizens have protested for since the disaster), but rather as an excuse to accelerate nuclear energy production, to modify Section 9 of Japan’s constitution to expand its military and participate once more in international conflicts, and reduce government transparency. These centrifugal legislative pushes have coincided with an inverse movement of discursive containment: Shinzō Abe’s repeated public assurances that the Fukushima disaster is fully under control, Japan’s radiation levels are safe, and the trauma has been neatly contained. As Christophe Thouny notes, the “3/11” moniker, aligning this ecological disaster with the World Trade Center attacks of 9/11, serves to discursively contain the event neatly within national borders and an international neoliberal order. The same scalar diagram is in play here: “A planetary event is thus neutralized by a containment that captures and internalizes the eventfulness of the catastrophe within a neoliberal world” (Thouny 2). This centripetal gesture leads, as Mitsuhiro Yoshimoto further argues, to a scalar expansion: through the linking 3/11 and 9/11, a circuit is actually closed between key scenes in the Pacific theater of the Second World War that U.S. 9/11 discourse restaged as the “war on terror,” including an Iwo Jima style flag raising at Ground Zero, the evocation of “a second Pearl Harbor,” etc. (Yoshimoto 31). Such are the historical-discursive vectors of eco-scalar breathing, which remake milieus at all scales to enable further scaling operations—in this case Japan’s re-militarization in response to increasing global insecurity.

As a number of authors have noted, Japan’s post-Fukushima script has played out like a perfect rehearsal of the diagram elaborated by Naomi Klein as “disaster capitalism,” which primarily entails “using moments of collective trauma to engage in radical social and economic engineering” (Klein 9). Here, the Japanese government’s disavowal of responsibility for the very collective trauma that it is capitalizing on is only made possible by the scalar difference between the cause and effect. The release of radioactive particles on 3/11 was the direct result of the government’s policy of promoting the deregulation and expansion of nuclear power as a form of particular concentration, but the inevitable closing of this scalar circuit in the form of radioactive dispersal is instead recoded as an external threat to the Japanese people, an exogenous assault lumped together with an increasingly hostile world from which the populace must be inoculated via militarization and ideological unification. Abe’s message is that the government resolves not particulates, but only molar bodies: individuals, infrastructure, the population. Only these bodies are visible, and they must be preserved and bolstered by every individual. 3/11 may have been an unwelcome event in the sudden visibility it brought to state nuclear policy and to radioactive particulates, but the neoliberal politics of the Abe government quickly harnessed both the concentration of destructive forces at the Fukushima site as an affective memorialization and call to nationalism as well as the dispersal of radioactive particles throughout a large swath of the country as a veil, a discursive return to invisibility and thus safety.

If disaster capitalism seems to have it both ways—to both hide its own inevitable disasters and to capitalize on them, this is because particulate technocracy’s basic operation is to effect the scalar coupling that harnesses the trans-scalar energies of one event and uses them to effect change in wholly alien domains. Yet even this work must be re-coded, shunted to another scale, contained, in order to enable eco-scalar breathing, and its attendant scaling of capital, to continue. As Aya Hirata Kimura notes in her study of women citizen scientists in post-Fukushima Japan, neoliberal discourse “propels individuals, communities, and nations to look forward to the future as pregnant with opportunities. This anticipatory outlook helps frame radiation as the product of a single, contained event” (Kimura 133). Thus Japan looks forward to the 2020 Olympics, to bringing new nuclear power plants online, to expanding its military, to growing its economy. All of this is predicated, of course, on discursively containing the fallout—literal and figurative—from Fukushima. “Rather than being portrayed as something still in the environment, radioactive contaminants are now seen as already contained and belonging to the past” (Kimura 142). Radioactive particles can easily be made to disappear if the discursive or instrumental apparatus that resolves their scale is shifted. Because the government controls the instruments that record radiation diffusion and concentration as well as the standards by which areas and concentrations are deemed safe, these bars can and were easily shifted.

This simplest of tricks—to resignify an environment as safe by changing the official threshold above which food is considered toxic, for example—is effective despite its hamfistedness because it harnesses the unstable status of the particle in relation to the human milieu. Radioactive particles aren’t individually detectable, and thus their presence is always contestable based upon the presence or absence of aggregate testing infrastructure and standards that render results as “safe,” “elevated,” etc. Particles, liminal objects that are neither fully visible nor invisible, often serve as conceptual and physical mediators of massively scaled processes or objects (such as global climate change) that Timothy Morton calls “hyperobjects.” “Hyperobjects seem to phase in and out of the human world. Hyperobjects are phased: they occupy a high-dimensional phase space that makes them impossible to see as a whole on a regular three-dimensional human-scale basis” (Morton 70). Hyperobjects exist at multiple scales at once, and shift freely between those scales. The radioactive isotope, for example, is produced through uranium enrichment, concentrated as a critical mass in nuclear power production (or the detonation of a nuclear bomb), and expands throughout the environment at the moment of release. This is a technical process, but the presence of the isotope and its effects do not appear as either continuous or linear. Radiation appears sometimes as various forms of illness, sometimes as genetic mutation, sometimes only virtually as possibility (such as during the Cuban Missile Crisis, negotiations between the United States and North Korea, etc.), and most of the time not at all. The radioactive particle is simultaneously local contamination, invisible power source, and millennial-scale waste. This leads Peter Van Wyck to argue that nuclear energy is in some ways unsignifiable; it is “matter without a place” (Van Wyck 5). We do not have an adequate vernacular of the nuclear, do not have an effective means to render it visible. In this sense radioactive particles are characterized by “absolute invisibility,” the radical semiotic condition of ecological threat more generally (Van Wyck 24).

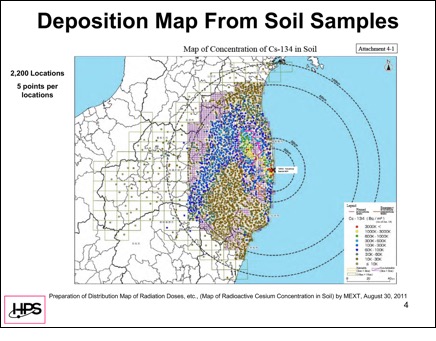

Despite the difficulty of tracking and signifying the particulate scales of the nuclear hyperobject in all of their dimensions, local efforts were made in the case of Fukushima by a loose network of (mostly) women acting as citizen scientists. Through rain, gravity, and wind, many of the airborne particles released from Fukushima’s melted reactors found their way into the soil (Figure 3), and thence into animals and plants. These bodies, as sites of mediation in the middle of eco-scalar breathing, could serve as measurable proxies for nuclear contamination at larger scales. Not long after the disaster, facing suspect government assurances that radiation levels outside of the immediate evacuation zone were perfectly safe, “citizen radiation-measuring organizations” began to spring up around Japan (Kimura 1). Most of these groups were comprised of women concerned about food safety. They typically purchased a scintillation radiation detector, set up shop in a home or existing local business, and opened their doors to anyone who wished to bring in food samples for testing. Their results were dramatic: “Not only did they identify hidden cases of contamination that violated government standards, they provided data on lower-level contamination, which many citizens felt was necessary to protect their health” (Kimura 111). That is, by testing far more samples than the government had, they were better able to track actual contamination that officials had “missed” (based upon its deliberately circumscribed testing)1 and levels of radiation that were potentially significant but happened to fall below the government’s arbitrarily assigned threshold (and which were therefore never reported to the public). Ironically, then, the greatest challenge to the Japanese government’s scalar elision came from the very scale passed over by neoliberal policy: the local community.

The community data generated by citizen radiation testers directly contradicted the government’s claims that no significant levels of radioactive cesium existed in Japan outside of the immediate site of the disaster. The data generated by citizen scientists “are able to enact a profound shift in reality, from the nonexistence of contamination to its existence” (Kimura 128). As a scalar politics of visibility, then, such citizen science works to draw back the curtain on scalar magic: particulate formations that ordinarily escape from sight (perhaps by government design) as they jump scales are here tracked through their concentration into and through food and its attendant industrial processes of production and distribution. This alternative tracking procedure, counterposed against a technocratic governmentality that accomplishes invisibility by calibrating technoscientific optics to filter out undesirable scales, disrupts the scalar diagram of that governmentality. It thus becomes a new scalar force that, from the state’s perspective, must be contained. The government’s response in this case was to contain political fallout by discursively reinforcing the norms of neoliberal subjectivity through a deployment of the concept of “fūhyōhigai,” or false rumors that harm the socio-political collective. Charges of fūhyōhigai were leveled at women who contradicted official government pronouncements of safety. Promulgators of fūhyōhigai were coded as harming the regional and national financial recovery after Fukushima, and thus as oppositional to the collective welfare of Japan. As Kimura argues, “After the Fukushima accident, the concept was used to describe people who avoided foods from affected areas as fearmongers who caused much suffering to the food producers” (Kimura 32).

Sometimes the government’s pushback against forms of subjectivity that didn’t align with neoliberal norms was more pointedly gendered, as in the deployment of the derogatory phrase “radiation brain mom” to “deride these concerned mothers as hysterical and irrational” (Kimura 28). Thus while radiation brain moms track the eco-scalar breathing of neoliberal capital, they are themselves tracked and coded by discursive distributions that simultaneously resignify and materially circumscribe their activities (many such citizen scientists were driven financially insolvent by 2012). As centripetal movements resolve into centrifugal ones and vice versa, the resulting scalar gradient is primarily mobilized to scale capital. Capital, then, is both the parasitic beneficiary of such movements, and one of the central engines by which this perpetual scaling machine is kept moving. Run out of money and suddenly you are face to face with a lack of scalar potential for escape, ensconced in the scale of your immediate environment. On March 13, two days into the disaster, the managers of Fukushima’s stricken facility issued the following announcement to their employees, over the loudspeaker: “We are going out to buy some batteries, but we are short of cash. If anyone could lend us money, we would really appreciate it” (Lochbaum, Lyman, and Stranahan 67).

Element, Sign, and Scale: Chemtrail Conspiracy Theory

Geoengineering, or the large-scale technological management of the Earth’s climate, remains at this point a mostly speculative suite of technologies and control regimes. For decades, geoengineers have invented, studied, and advocated for various technical interventions capable of scaling up to the global level. The motivation for these systems, which at full scale would be the most expensive and complex techno-social systems deployed in human history, is the mitigation of global climate change. While most of these proposals would not reverse or nullify climate change, they would temporarily mitigate some of its symptoms, generally by reducing the amount of sunlight that would reach the Earth’s surface. Proposed geoengineering methods range from giant space-based mirrors to fleets of “marine cloud brightening” ships to ocean iron fertilization to stratospheric aerosol injection. This last, referred to by leading geoengineer Keith David as “global sun block,” would mobilize a worldwide force of airplanes capable of spraying vast quantities of highly reflective metallic particles into the upper atmosphere on a continuous basis.2 For geoengineers, visible industrial processes that produce greenhouse gases at local sites cause centripetal dispersals of these particulates that enable them to evade any form of control. Geoengineering proposals append to this movement another stage that renders a new set of particulates once again visible and manipulable, “rescuing” the unintended outcomes of climate change by enrolling them back into regimes of technocratic control.

If Fukushima represents the disaster-form of particulate technocracy, no matter how frequent and thus normalized that form may be in what Ulrich Beck refers to as “risk society,” in which “the unknown and unintended consequences come to be a dominant force in history and society” (Beck 22), it nonetheless remains a punctuated event around which a particularly urgent but temporary set of particulate and political movements mobilize. As I noted in the previous section, neoliberal governmentality is particularly adept at manipulating the temporality of the disaster vis-a-vis anticipatory mobilizations of affect and future centripetal concentrations of capital (investing in future nuclear infrastructure, national economic recovery, etc.). This presents a further problem for resistance media that would counter such forms of control by tracking (rendering visible) their particulate movements. Put another way, if radiation brain moms have found a way to extend and maintain particulate visibility in the aftermath of a violent disaster, how might we accomplish this for the same forces when they operate under normal conditions of slow violence, degrading and polluting environments over extended temporal and spatial scales, when this violence is invisible to short-cycle media by default? (Nixon 2). One possible answer to this question emerges from an unlikely source: a particular form of conspiracy theory.

If professional geoengineering discourse stabilizes a set of scalar relationships deployed against and through the ocean and sky as nodal surfaces in a scalar network designed to resignify the Earth as an object of human command and control, then the “chemtrail” conspiracy movement produces a counter-discourse that treats particulate technocracy as fully material, visible, and legible inscription. This is what we might call, after Richard Hofstadter, the “paranoid” response to geoengineering, as it takes the discursive form of conspiracy theory.3 The conceptual and narrative linchpin of this informal global movement is the shared belief that a secret, large-scale geoengineering program is not just on the drawing board, but currently underway, blanketing the globe with toxic particles sprayed into the stratosphere. “Why is this being allowed to be sprayed continuously all over the United States, all over the world?” demands Karen Johnson in the most popular full-length chemtrail documentary film, What in the World Are They Spraying?. “Who is paying for this?”

Chemtrail discourse borrows from geoengineering tropes, but transforms them into a kind of trans-scalar semiotics. This group’s primary signifier of geoengineering is the “chemtrail,” a white line traced against a blue sky (Figure 4). The chemtrail looks, to the uninitiated observer, just like a jet contrail, the mixture of oil and water vapor that is emitted from jet airplane engines and sometimes partially crystallizes in the upper troposphere, forming tracks or traces on the sky. Chemtrail readers discern malevolent purpose in these atmospheric inscriptions, calling attention to the mark of the human on the sky’s surface. “Five years ago, our skies were typically blue” explains Dane Wigington in the same documentary. “Now you see it’s covered with lines, and haze, and virtually nothing you see on the horizon, nothing you see in the sky above us, is a natural cloud… the sky has a very dirty look to it” (Wittenberger 2010). While evoking industrialism’s temporally and spatially large-scale diffusion of toxic particulates into the atmosphere, in the specifically technoscientic context of geoengineering, chemtrail rhetoric serves to render this elemental medium explicitly post-natural.

The chemtrail is both a singular entity and a multiplicity, a mark and a cloud of toxic particles. These signs are ephemeral, but like Keith’s latest stratospheric aerosol proposal, which includes speculative levitating nano-particulate discs,4 their scalar instability is modulated by the intermediator of the particle. In the chemtrail narrative these metallic particles inevitably rain down and contaminate water, soil, and body. Crucially, however, chemtrail media attempt to register the particle’s continued presence and render it visible at these later, centripetal stages. Chemtrail readers accomplish this by assiduously testing local soil and bodies of water, as well as their own bodies. These tests typically take the form of samples sent off to labs. The toxicity reports that come back are prominently featured in chemtrail media: posted online or shown to the camera in chemtrail documentaries. They often do indeed show elevated levels of potentially dangerous metals and other contaminants. Just as in the case of citizen radiation testing centers in Japan, the key scale of resistance for the chemtrail community is the local environment: soil, blood, and water. These function as both sites and media: as toxic particles concentrate in particular bodies, they become signifiers of global processes of power and contamination. Particles concentrate in them at the same time that they constitute and discursively amplify signs. The toxic local landscapes of particular communities are certainly real, and re-emerge through toxic cartography as visible milieus, no longer elided by neoliberal capital, but rather alive with invisible particles that have traveled some way or another from sites of industrial activity. But if chemtrail conspiracy theorists have taught themselves to become assiduous citizen scientists and toxic cartographers, they nonetheless place the greatest symbolic weight on the image of the chemtrail itself.

The chemtrail arrests these toxic particles at the visible stage of eco-scalar breathing and enrolls them as images and tropes in a vast chemtrail media ecology consisting of thousands of such signs and personal narratives of toxic landscapes. It is this medial context that harnesses the highly visible jet contrail and articulates it to the invisible particles of environmental contamination in a process commensurate with radiation brain moms’ harnessing of the highly visible 3/11 event to sustain the visibility of dispersed radioactive isotopes throughout the food distribution system.

In chemtrail media, images of chemtrails are continually recombined and remixed into various web archives, documentary films, and other online media, collectively forming a media ecology of toxicity. Chemtrail conspiracy narrative appropriates the speculative fiction frame of geoengineering narrative and radically alters its discursive genre: from could-be-possible to it’s-already-happening, from rendering the speculative visible as possibility to documenting the invisible. Dane Wigington asks, in a second chemtrail film, Why in the World Are They Spraying?, “Why would we not believe it’s happening when what we see in the sky matches exactly the expressed goal of numerous geoengineering patents?” Of course, what chemtrail readers “see” in the sky is more than a white line: the chemtrail is a multi-scalar signifier, an assemblage of indeterminate particles. It is the trans-scalar potential of the particle—whether the radioactive isotope, the CO2 molecule, or the “smart” nano-particle—that catalyzes narratives of global contamination, terraforming, and conspiracy. That is, in order to follow the scalar transformations of these assemblages, _chemtrail readers allow their narrative scales to piggyback on the movements and potential movements of the particles themselves.

In modulating their narrative and subjective scales to those of eco-scalar breathing, chemtrail readers invert geoengineering’s elemental scalar formula. For them, the atmospheric-global is not the final stage in an engineering process that begins visibly at local scales with the burning of greenhouse gases and then becomes invisible as those CO2 molecules diffuse to the height and scale of the atmosphere. Rather, in chemtrail media the global scale of atmospheric particulates is visible and is under direct human control. Karen Johnson explains, in What in the World Are They Spraying?: “This has been planned. We have elites, I don’t know what you want to call them: one-worlders, Illuminati, whatever you want to call them… but these people who don’t care about the average person” (Wittenberger). The chemtrail, then, is an originary inscription on a legible surface, produced by a global order of shadowy “elites.” The chemtrail as aesthetic arrests a cycle of dispersal and condensation that quickly becomes asignifying as it changes elemental form. As particulates sprayed into the atmosphere rain down and concentrate in the soil, in bodies of water, and in human organs, they have to be tracked through increasingly indirect means, as the traces they leave have been scale-dissociated from the networked flows of capital, power, and technics that produced them. Where geoengineers see these local, earthy (solid) stages of the particulate as precisely manipulable, chemtrail readers on the other hand—intent not on effecting an intervention into global climate dynamics but rather on the making visible of particulate technocracy’s inscriptions—frame these earthy concentrations as effects rather than causes, as systems gone haywire following the injection-inscription of global command and control. The local, here, is not an originary site of technocratic agency but rather a medial site that records the overwhelming amplification of particulate inscription.

What the chemtrail conspiracy community is attempting to render visible, in the best way it knows, is trans-scalar power itself: the networked dynamics of capital, colonialism, and industrial activity that concentrically distribute toxic particles throughout an environment, only to have them concentrate in certain bodies. The same abstract diagram of eco-scalar breathing describes these movements of particles, movements of capital into privileged nodes of accumulation, and the formation of social and political networks with continually shifting nodes of privileged passage and/or accumulation. This formation of power has proven extremely difficult to resist, or even apprehend, because it spans multiple semiotic registers (from identity to technology to policy to knowledge to narrative) and multiple scales (from the particulate to the planetary). Val Plumwood has characterized this situation as the fourth stage in western culture’s staged battle between “reason” and “nature,” characterized by the subjugation of the latter: “In the fourth stage, reason systematically devours the other of nature. The instrumentalisation of nature takes a totalising form: all planetary life is brought within the sphere of agency of the master (Self). Devouring is the project of the totalising self which denies the other’s difference” (Plumwood 192-3). In its neoliberal form, this dynamic amounts to a subsumption of all forms of production and value into a freescaling market assemblage whose totalizing logic not only denies any outside, but enables the endless scaling of elements within its circuits. Eco-scalar breathing is an appropriation and resignification of “nature” into the flows and logics of neoliberal capital.

I have argued throughout this paper that the particulate dynamics of neoliberal power produce, from the perspective of the individual subject, an uneven scalar spectrum whereby certain scales are rendered visible and others invisible, like occasional windows in an otherwise opaque wall. Watching a particular window reveals a magic show in which a variety of entities appear and disappear as they change scales. On the other hand, attempting to track one of those entities through its scalar phase changes results in a similar magic show marked by repeated mysterious disappearances and dramatic re-materializations. In this shifting milieu, the problem of visibility is a problem of scale, which in turn manifests itself as a dual problem of perspective and signification. The problem is less one of inventing a visible semiotics to express the invisible and more one of harnessing the visible transition points of eco-scalar breathing in order to elongate, develop, and sustain them into ways of seeing across scalar transformations.

Chemtrail readers offer one potential response to these conditions: the deployment of the idiom of conspiracy to track the intertwined dynamics of particle, sign, and scale. Under these conditions, conspiracy theory may function not as a denial of evidence but as a deeper sensitivity to shifts of register and scale. Indeed, Fredric Jameson has famously referred to conspiracy theory as “the poor person’s cognitive mapping in the postmodern age” (Jameson 1988: 356). That is, within a totalizing system that controls the semiotic registers of any possible apprehension or resistance, to locate oneself as a subject (as opposed to merely experiencing one’s subject position) within continuously shifting flows of meaning requires a radical form of connecting invisible dots. Privileged forms of cognitive mapping require intimate knowledge of the determining dynamics of the system. Non-privileged forms require the building of a map from the ground up; in this case Chemtrail media’s particular form of toxic cartography begins with one’s internal organs or local water supply, rendering visible a trail of toxic particles that quickly jump from scale to scale in a chain that most forms of apprehension would find impossible to sustain. The grounding element that anchors the scalar chain is, for chemtrail conspiracy theorists, sickness: sickness of the self, of the soil, of the community, of the sky itself, and of global power structures. This is not an accidental thematics: as Heather Houser has argued, “Sickness is a powerful analytic for inquiry precisely because it offers new perspectives on how these macrosocial forces penetrate individual human bodies and how embodied experience might transform these forms in turn” (Houser 12). Sickness is multiscalar, and a radical semiotics of sickness capable of spanning disparate registers (humanism, science, elemental signification) and disparate scales offers some hope of tracking the particulate flows that enable the non-continuous scalings of capital, power, and environmental toxicity.

Critics of conspiracy theory often charge that it is obsessed with attributing to one particular individual or group the complex evils of modernity, and that this is the essence of its error.5 This is certainly true of many conspiracy theories, such as those that blame George W. Bush and the CIA for masterminding the 9/11 attacks on the World Trade Center or, during the 2016 US presidential election, blamed Hillary Clinton for all manner of evil plots against America’s interests, from Benghazi to “Pizzagate.” Foucault refers to the social context that demands an author be attributed to the circulation of a text the “author-function,” and notes that one of its key characteristics is penal appropriation: “the author arises when he becomes subject to punishment” (Foucault 1984b: 108). In chemtrail narrative, this is precisely the author-function. Very real environmental and social crimes have been committed, and chemtrail readers are primarily concerned with making those crimes visible, of arresting their signifiers at the points at which they become legible as elemental inscriptions. But Chemtrail narrative is scale-aware, and thus no univocal author-perpetrator can be named. Such diffuse signifiers are “elites,” “one-worlders,” and “the Illuminati” stand in for a plural and indeterminate subject. If Chemtrail conspiracy media cannot name a localizable and definite villain—an author of disaster capitalism—this is because it is primarily concerned with signifiers across changes of scale, of eco-scalar breathing as a process. Like Oedipa Maas, the protagonist in Pynchon’s greatest novel about paranoia and conspiracy theory, The Crying of Lot 49, the chemtrail conspiracist must be content chasing particles as they phase in and out of view, ever revealing fragments of vast and minuscule structures, yet never the complete outline of a center: “Oedipa wondered whether, at the end of this (if it were supposed to end), she too might not be left with only compiled memories of clues, announcements, intimations, but never the central truth itself, which must somehow each time be too bright for her memory to hold” (Pynchon 69). It isn’t very satisfying, this lack of a definite and stable agent, or meaning, or structure, yet this indeterminacy matches the scalar peregrinations of the particle. To chase something that is everywhere, yet mostly invisible, and always changing, a certain degree of paranoia is prerequisite.

Richard Hofstadter argues, in his famous essay, “The Paranoid Style in American Politics,” that the conspiracy theorist sees all of history as a conspiracy. “He traffics in the birth and death of whole worlds” (Hofstadter 29). The scalar jump made by the chemtrail conspiracy theorist to “whole worlds” seems rather appropriate in the context of increasingly toxifying landscapes. In the Anthropocene, this connective leap from the toxic particle to the planet is no longer an analytic liability, but rather an essential ingredient of elemental media. What we learn from the chemtrail conspiracy theorist is not a plausible narrative of causality, but rather a practice of reading that makes visible the trans-scalar particulates of neoliberal technocracy and its attendant flows of power across and through the scales of elemental media.

Conclusion: Equivalence and Catastrophe

Philosopher Jean-Luc Nancy, writing on Fukushima, argues that in our current milieu all catastrophes are equivalent in the sense that “the regime of general equivalence henceforth virtually absorbs, well beyond the monetary or financial sphere but thanks to it and with regard to it, all the spheres of existence of humans, and along with them all things that exist” (Nancy 5). Neoliberal, technocratic capitalism is capable of absorbing anything and rendering it equivalent with anything else. Because there is nothing really outside of capital, Fukushima cannot be regarded a natural disaster, an isolated accident. On the contrary, “There are no more natural catastrophes: There is only a civilizational catastrophe that expands every time” (Nancy 34). Nancy’s argument that catastrophe has become a single unified assemblage coterminous with civilization itself echoes Anthropocenic arguments that there is no longer an outside to the human’s destructive mode of life and production. What both describe is a scalar saturation that, for all of its inertia in deep time and planetary space, remains only sporadically and discontinuously visible, and thus unavailable for the effective mapping of alternative potentials.

I have been arguing that neoliberal capital’s efficacy in mobilizing multiple domains across multiple scales is not arbitrary, nor the result of a single vector of expansion and massification as is commonly argued in some Marxist circles. Rather, it is the development of particulate technocracy, a regime of control that functions through simultaneous incorporation and division according to scale, coupled with a form of mediation that pushes the particulate to rapidly switch scales. Yet something like a medial conservation of energy requires that scalar movements alternate between centrifugal expansions and centripetal concentrations. The former diffuse the particulate widely, rendering its inscriptions mostly invisible. The latter concentrates flows at particular sites or in particular bodies, rendering them both sick and visible, yet also contained.

The particulate is a privileged medial object in the twenty-first century. As a paradoxically formless form, the particulate enables radical scaling operations and their consequent molar shifts of scale. Particulate technocracy, in harnessing the diagram of eco-scalar breathing, mutates scalar transformation into a post-natural coupling of nonhuman forces and human products (particles of various stripes). Successive dispersals and concentrations are not autonomous nor disconnected, but linked through particular technocratic media infrastructures into smooth transfers across both scales and domains. I’ve attempted to explore in this essay how forms of governmentality predicated upon subjectivation (ideology), technological infrastructure, and “natural” forces can be brought into (or irrupt into) alignment to effect such parallel scaling.

In post-catastrophic moments savvy medial mobilizations of trans-scalar energies can render these flows visible again by articulating their phased structure to the momentarily visible scale shifts of ecological disaster. The longer term version of this trans-scalar tracking requires a mutation in subjectivity itself, a trans-scalar reading practice capable of proactively resignifying elemental surfaces as gradients for these general civilizational scale jumps, as practiced by chemtrail readers. Absent this scale literacy, fixed perspectives within this seemingly total catastrophe will only see particulate forms winking in and out of existence. Coming to see this as the scalar magic trick that it is requires a new scale-fluidity, an ability to follow the particles, wherever they may lead.

Works Cited

Beck, Ulrich. Risk Society: Towards a New Modernity. SAGE Publications Ltd, 1992.

Billig, Michael. Fascists: A Social Psychological View of the National Front. Academic Press in co-operation with European Association of Experimental Social Psychology, 1978.

Foucault, Michel. “What Is an Author?” The Foucault Reader, edited by Paul Rabinow, Pantheon, 1984, pp. 101–20.

Harvey, David. A Brief History of Neoliberalism. Oxford University Press, 2006.

Hofstadter, Richard. “The Paranoid Style in American Politics.” The Paranoid Style in American Politics, and Other Essays, Harvard University Press, 1996, pp. 3–40.

Horton, Zachary. “Going Rogue or Becoming Salmon?: Geoengineering Narratives in Haida Gwaii.” Cultural Critique, vol. 97, Oct. 2017, pp. 128–66.

Houser, Heather. Ecosickness in Contemporary U.S. Fiction: Environment and Affect. Reprint edition, Columbia University Press, 2016.

Jameson, Fredric. “Cognitive Mapping.” Marxism and the Interpretation of Culture, 1988, pp. 347–57.

Keith, David W. “Geoengineering the Climate: History and Prospect.” Annual Review of Energy and the Environment, vol. 25, no. 1, 2000, pp. 245–84. Annual Reviews, doi:10.1146/annurev.energy.25.1.245.

---. “Photophoretic Levitation of Engineered Aerosols for Geoengineering.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 107, no. 38, Sept. 2010, pp. 16428–31. www.pnas.org, doi:10.1073/pnas.1009519107.

---. “Research On Global Sun Block Needed Now.” Nature, vol. 463, no. 7280, Jan. 2010, pp. 426–27. www.nature.com, doi:10.1038/463426a.

Kimura, Aya Hirata. Radiation Brain Moms and Citizen Scientists: The Gender Politics of Food Contamination after Fukushima. Duke University Press Books, 2016.

Klein, Naomi. The Shock Doctrine: The Rise of Disaster Capitalism. 1st edition, Metropolitan Books, 2007.

Latham, John, et al. “Marine Cloud Brightening.” Philosophical Transactions. Series A, Mathematical, Physical, and Engineering Sciences, vol. 370, no. 1974, Sept. 2012, pp. 4217–62. PubMed Central, doi:10.1098/rsta.2012.0086.

Lochbaum, David, et al. Fukushima: The Story of a Nuclear Disaster. Reprint edition, The New Press, 2015.

Morton, Timothy. Hyperobjects: Philosophy and Ecology after the End of the World. Univ Of Minnesota Press, 2013.

Murphy, Michael J. Why in the World Are They Spraying? 2012.

Musolino, Stephen V. Technical Assessment of Environmental Contamination From the Fukushima Dai-Ichi Reactors. U. S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission, 2012. https://www.nrc.gov/reading-rm/doc-collections/commission/slides/2012/20120911/musolino-20120911.pdf.

Nancy, Jean-Luc. After Fukushima: The Equivalence of Catastrophes. Translated by Charlotte Mandell, 1st edition, Fordham University Press, 2014.

Nixon, Rob. Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor. Harvard University Press, 2011.

Ochiai, Eiichiro. Hiroshima to Fukushima: Biohazards of Radiation. Springer, 2013.

Peters, John Durham. The Marvelous Clouds: Toward a Philosophy of Elemental Media. University Of Chicago Press, 2015.

Plumwood, Val. Feminism and the Mastery of Nature. Routledge, 1994.

Popper, Karl. “The Conspiracy Theory of Society.” Conjectures and Refutations: The Growth of Scientific Knowledge, 2nd Edition, Routledge, 2002, pp. 165–68.

Pynchon, Thomas. The Crying of Lot 49. Bantam Books, 1966.

Thouny, Christophe. “Planetary Atmospheres of Fukushima: Introduction.” Planetary Atmospheres and Urban Society After Fukushima, 1st edition, Palgrave Macmillan, 2017, pp. 1–18.

Wittenberger, Paul. What in the World Are They Spraying? 2010.

Wyck, Peter van. Signs of Danger. First edition, University of Minnesota Press, 2004.

Yoshimoto, Mitsuhiro. “Nuclear Disaster and Bubbles.” Planetary Atmospheres and Urban Society After Fukushima, edited by Mitsuhiro Yoshimoto, 1st ed. 2017 edition, Palgrave Macmillan, 2017, pp. 29–50.

Footnotes

-

According to Kimura, citizen scientists found over one thousand cases of food contaminated by cesium above the government standards (Kimura 109). ↩

-

For a comprehensive overview of proposed techniques and advocacy for increased funding for feasibility studies, see Keith, “Geoengineering the Climate: History and Prospect” and “Research on global sun block needed now.” For an outline of the marine cloud brightening technique by its leading advocate, see Latham et al., “Marine Cloud Brightening.” For a study of one actual attempt at geoengineering using the technique of “ocean iron fertilization,” along with its cultural and political fallout, see Horton, “Going Rogue or Becoming Salmon?” ↩

-

See Hofstadter’s classic essay on conspiracy theory, “The Paranoid Style in American Politics,” in which he argues that such discourses are a danger to liberal society. ↩

-

See Keith, “Photophoretic Levitation of Engineered Aerosols for Geoengineering.” ↩

-

See, for example, Karl Popper’s “Conspiracy Theory of Society,” in which he argues that conspiracy theorists “assume that we can explain practically everything in society by asking who wanted it” when actual historical events almost never play out according to anyone’s intentions, and thus sufficiently complex explanations of social events must “explain those things which nobody wants—such as, for example, a war, or a depression” (14). Michael Billig deems this tendency to attribute complex causes to individuals, assuming them to be the direct effects of intentional action, “attribution error” (Billig 161). ↩

Cite this article

Horton, Zachary. "Toward a Particulate Politics: Visibility and Scale in a Time of Slow Violence" Electronic Book Review, 1 December 2019, https://doi.org/10.7273/9wr4-k121