“You’ve never experienced a novel like this”: Time and Interaction when reading TOC

Steve Tomasula's TOC is hard to explain, according to Alison Gibbons. You're better off experiencing it in all its multimodal and multimedial complexity. Using human computer interaction and narrative theory, Gibbons shows that the emergent, singular, fractured temporality of reading TOC raises the bar for the new media book.

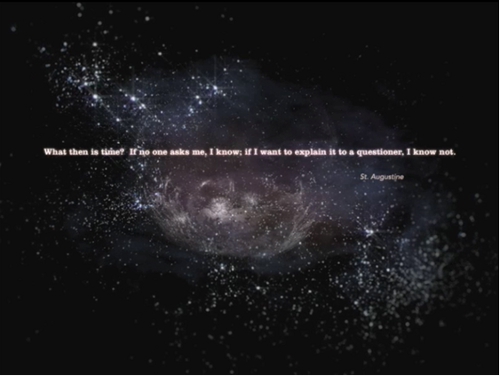

“You’ve never experienced a novel like this” asserts the publisher’s information for TOC (2009), Steve Tomasula’s new-media novel. This claim, presumably, is founded precisely on the new-media nature of TOC, its delivery of text, spoken word, music, graphics and animation all harnessed and combined in a computerised narrative. The publisher’s information certainly makes some bold claims. TOC is “a breathtaking visual novel,” “a multimedia epic”; “A new-media hybrid, TOC reimagines what the book is, and can be.” And I find myself powerless to disagree. “You’ve never experienced a novel like this” speaks volumes, for experience is at the heart of TOC, and crucially the experience is yours. When TOC loads up on your laptop, you find yourself confronted by a galactic image, a violet light profile at its center bounded by clusters of stars. Rhythmical archaic music starts to play as the camera zooms in and on the screen the words appear: “What then is time? If no one asks me, I know; If I want to explain it to a questioner, I know not.” Attributed to St. Augustine, these lines come from Confessions, an autobiographical contemplation on the workings of God within his life, written (or dictated) by Augustine between 386-430 AD. Importantly, this cues the novel’s central theme of time.

Figure 1: Screenshot of the Epigram of TOC

“What then is time?” poses a rhetorical question, with an important temporal marker. The deictic adverb works to heighten the question’s import: This is an ongoing debate, as yet unresolved. The remainder of the quotation, “If no one asks me, I know; If I want to explain it to a questioner, I know not,” features a syntactic parallelism. Through the use of the conditional, this creates two hypothetical scenarios, the structural equivalence of which works to set up a paradox. In the first half, a questioning subject is negated, leaving a profiled first-person speaker residing in his unchallenged understanding of time. In the second structure, the negation has moved: the first-person speaker is the subject of both clauses; a questioner is now present; and the speaker’s understanding of time has been negated. The negation, and the fact that this negation provides an obvious deviation from the previous sentence’s focus (“I know”), foregrounds the loss of knowledge. Thus time is cast as inherently unknowable. Discussing Augustine’s famous meditation, Isham and Savvidou accept Augustine’s ideas as poignant and relevant because “‘time’ is an elusive concept: in one sense we think we know exactly to what it refers, but when we try to pin it down it slips away – like a chimera, a will-o’-the-wisp” (8). Some time passes (it is hard to tell how much exactly since your eyes are transfixed on the screen). The quotation from St. Augustine fades and a voice begins to talk over the music: “A distant world shines from another’s past that is simultaneously our future. Is this a ripple in time? Or in life?” Again, the novel presents a paradox: “A distant world shines from another’s past that is simultaneously our future.” Although the illogicality of this statement has a number of sources, it stems from the way in which time is understood in terms of space. This is a conceptual metaphor (TIME IS SPACE) and can be seen in everyday phrases such as the commonplace “time passes” which opened this paragraph, or “You have your future ahead of you” / “Leave the past behind.” Being told to “focus on the here and now,” for instance, shows the present being understood as both temporally and spatially immediate. As such, we can represent our spatial understanding of time as follows:

Past > Present > Future

The arrows in this representation depict the cognition of time as forward motion; time’s directionality, precisely time passing. For something to be both past and future is evidently a contradiction, but this is heightened by Tomasula’s use of the temporal adverb “simultaneously” and further troubled by the visual prompt in “A distant world shines … .” Coupled with the galactic image on the screen, you can only assume that the bright light profile is the distant world being referenced. Two important effects emerge from such multimodal cognitive indexing. Firstly, you include yourself within the possessive first-person “our.” In doing so, the boundary between narrator and reader seemingly collapses since you assume a shared subjective positioning with the narrator and a shared space in the form of “our future.” Secondly, in consequence of the first effect, the distant world on the screen, the storyworld of TOC, comes to represent that future. As the questions begin - “Is this a ripple in time? Or in life?” - the image begins to alter. The star clusters move towards the center, and the view of the distant world starts to zoom in. The letters T O C appear on the screen, and the stars flitter through the O as though pulled in by a central force. In terms of visual perception, newness and motion work here to create an attentional zoom (see Carstensen 2007 and Stockwell 2009), which in turn gives the impression that you too, the reader of TOC, are moving towards this distant world, moving towards the future which is simultaneously another’s past. In effect, you are time travelling; moving from your present, where you sit at your laptop, into the world of TOC. In her introduction to the edited collection Time, Ridderbos asks, “Are we now, more than a millennium and a half after St. Augustine found himself in this unfortunate position, better equipped to shed some light on the nature of time?” (2002: 1). Perhaps not, but TOC certainly evokes contemplation. In this article, I consider the ways in which TOC uses multimodality and Human Computer Interaction (HCI) to foreground temporal experience during its reading process and/or performance.

TOC**, new media, and temporal ontologies**

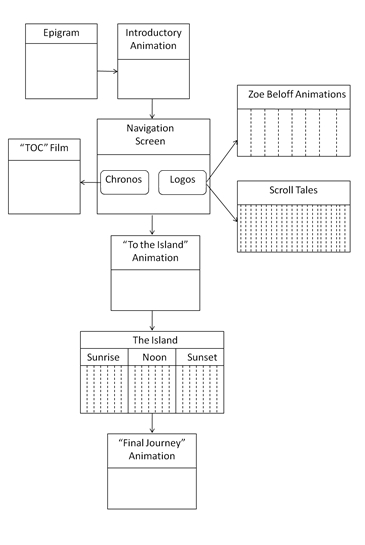

New media artefacts foreground the way in which readers interact with texts. As members of the Digital Fiction International Network make clear in their [S]creed, “digital fiction involves a different kind of connection with the text because we sit in front of a computer, bodily integrated with the machine, and at the same time ontologically separated from the world that it describes.” Moreover, because new media novels like TOC employ multimodal and multimedial representation, they are able to generate multisensory experiences that cognitively engage the reader/viewer/user on verbal, aural, visual, and kinaesthetic levels. The reader’s interaction with the new media text often has an influence on the structural ordering of the narrative. As Benford and Giannachi note, the “relationship between time and interaction has been a longstanding concern within HCI” (73). Similarly, new media artists Vaupotič and Bovcon cite “the complex ways in which the new media object entails and actively structures its own temporality” (503) as an important issue in the field of fine arts and in HCI design. Like many digital fictions (hypertext being the most obvious example), TOC has a multilinear narrative structure, allowing the reader a certain degree of navigational freedom, selecting different episodes and thus partly structuring the order in which elements in the narrative are read. Nevertheless, the narrative of TOC as well as the way in which you interact with it does have clearly defined limits. As shown in figure 2, TOC features a number of animations and filmic sequences. The “Navigation Screen” and “The Island” constitute the main sections of the novel in which the reader can interact with the text and select narrative pathways. The dotted lines within the “Zoe Beloff Animations,” the “Scroll Tales” and “The Island” represent the fact that these sections are composed of a number of different episodes. As a reader, you therefore encounter these episodes in whatever order you choose, but within the constraint of their overarching narrative section. Generally speaking, TOC’s interactive design is formed as a vector with side branches, defined by Ryan as “a determinate story in chronological order, but the structure of links enables the reader to take short side trips to roadside attractions” (249). To reduce the narrative of TOC to this statement would be a simplification, but the comparison suggests the way in which its design is hierarchical, imposing a central narrative pathway that permits navigational freedom at certain junctures

Figure 2: Narrative Structure for TOC

The impact of the reader’s interaction on narrative order also has significant implications in terms of the temporality of the text and this is reflected in the novel’s title TOC. On one hand, TOC is a culturally-accepted attempt at phonological iconicity, representing the sound of the even beat of the hands of a clock – Tic Toc. On the other hand, TOC has more than just temporal reference. At the end of the epigram, you see the letters T O C appear on the screen. Depicted thus, with expanded spacing in terms of typographical disconnectivity (for more on the semiotics of typography, see Van Leeuwen 2005; 2006; Nørgaard 2009), each letter is emphasised, suggesting the abbreviation “T.O.C.,” indicative of “Table of Contents.” Understanding “TOC” as both title and table of contents presents some interesting ramifications. In Paratexts, Genette contends that a work’s title has three functions: a principal function of designating the work itself, and two supplementary functions of indicating subject matter and tempting the reading public. Genette further divides the function of indicating subject matter into thematic, for the text’s content, and rhematic, for the text’s formal and generic properties. TOC is a combination of both the thematic and rhematic. Thematically, it is a text that is about time. However, it is also rhematic since it is a text that’s temporal order, in terms of your progression through it, is discontinuous and dependent on reader choices. A book’s table of contents announces both what the book contains as well as the order in which the sections appear. As a new media novel, with forking narrative choices, TOC is a significant title: It both meditates on time as a conceptual structure and demonstrates the importance of time as a structuring device by ensuring that the reader’s choices inform the experience of narrative chronology.

Interacting with TOC, or casting your pebble

The Epigram, discussed earlier, leads to the introductory animation. The image of a floating cork can be seen in the bell jar, and words move across the top of the bell jar; the image gives way to an island scene, and then to an ornate golden machine (later to be identified as the influencing machine). Throughout this animation, a narrator introduces the plotline of TOC. It is a mythic tale of Ephemera, a queen in exile, who whilst leading her followers to new land, gives birth to twin sons, Chronos and Logos. However, during the birth, the ship crosses into a new time zone, with one twin born on either side. As you experience TOC, you hear the narration while simultaneously seeing the moving sentences across the top of the bell jar:

| Narration | Moving Type |

| One son was born early Friday morning. | 12:05 A.M., January 1, XX85 |

| An hour later, after crossing into a new time zone, a second son was born on Thursday night. | 11:55 P.M., December 31st, XX84 |

As the moving type makes clear, crossing into a new time zone has serious consequences in terms of time and birthright. Years later, when it comes to the succession to the throne, an argument ensues between the two brothers. The narrative explains, “Chronos, having been born first, insisted that he was the eldest and that the throne should be his by birthright, while Logos demanded the same privilege having been born at an earlier date.” This disagreement becomes an argument, then a fight, and then an ongoing feud. The narration to this animation closes with the following words:

Occasionally, a philosopher might stop by to wonder at the commotion, or a historian might listen for a while looking for a way to organise a plot, but even they would shake their heads and walk away after perhaps dropping a pebble into one of the boxes that someone had set up so that the curious could wager on which ever brother the moment lead them to believe would win.

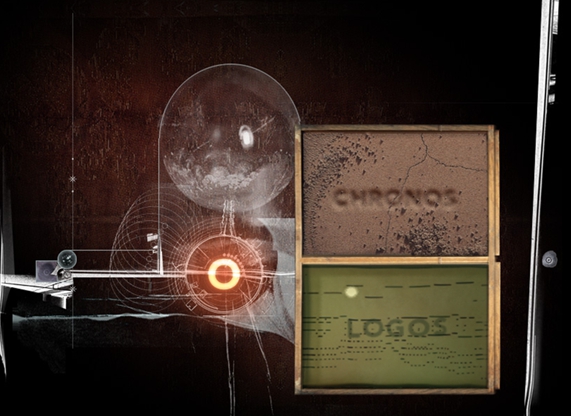

On the screen, the bell jar is now empty. The image zooms out, in the process forming the navigation screen. The bell jar stands at its center and on the right hand side, there are two boxes. In one appears to be sand imprinted with the name Chronos, while in the other appears to be water, with shadows casting the name Logos. Moving the cursor around the screen, you discover a small, roundish, grey object on the far right of the screen. The cursor icon hovers over it, becoming a small hand, and so, you realise, you can pick up this object. The object is in fact the representative image of a pebble, and thus you are able to deduce through narrative inference that the next step in your experience of the novel is to pick up the pebble and cast it into either the Chronos or Logos box, backing whomever you believe should succeed to the throne.

Figure 3: Screenshot of the Navigation Page for TOC

The act of casting your pebble is the first opportunity for interactivity in TOC. As such, doing so alters your current relationship with the narrative in that you become a narrative participant in a way that you previously were not. In other words, the act places you in a subjective alignment with the philosophers and historians mentioned by the narrator. Elsewhere in reference to printed multimodal fiction (see Gibbons 2008; forthcoming 2010a; forthcoming 2010b), I have described such alignment as a form of “doubly deictic subjectivity.” The term, and that which it designates, is an extension of Herman’s notion of “doubly deictic you” in which he suggests that the polysemic reference available to the second-person pronoun can at times work to point simultaneously to two entities, one virtual and one actual, conflating a fictional self or textual “you” with a real reader. Doubly deictic subjectivity involves the same convergence of character and reader, created not through pronominal reference but through the demands of the multimodal text itself. In the case of TOC, its interactive design compels the reader into kinaesthetic activity, a performative movement which replicates the actions of the philosophers and historians. Notably, my use of doubly deictic subjectivity stemming from the multimodal printed text is in line with work on digital fiction and new media narratives such as TOC. Ensslin similarly talks about “double situatedness”:

The double situatedness of the body implies, on the one hand, that user-readers are “embodied” as direct receivers, whose bodies interact with the hardware and software of a computer. On the other, user-readers are considered to be “re-embodied” through feedback that they experience in represented form, e.g., through visible or invisible avatars. (158)

The doubly deictic subjective alignment of reader with philosopher or historian in TOC takes on even greater significance. Casting the pebble into one of the boxes in TOC is not simply an empty performative activity, for doing so unlocks new parts of the narrative. The action therefore resonates particularly with the description of the historian who is ‘looking for a way to organise the plot’. Ryan categorises interactivity and immersion as dichotomous experiences, moving between immersion and deimmersion through interactivity. In doubly deictic subjectivity such as this, however, the interactive performance involves a split displacement whereby the reader is both self-consciously aware of his/her own physical interaction and immersed through re-embodiment. This is precisely because the interactive performance has such direct links with the narrative action.

To more explicitly signal the connection of double deixis with my topic of temporality and interaction, it is helpful here to recall Genette’s work on frequency as well as the distinction between story, the chronological events of the narrative, and discourse, the order in which they are narrated. Since in moments of doubly deictic subjectivity, the reader’s actions are vital, I’d like to make the addition of a further category – process, the way in which narrative events are received and experienced by the reader. We can say that at this point in the narrative, a philosopher or a historian are described as “perhaps dropping a pebble into one of the boxes.” This is something that happens “occasionally,” though, so a disjunction between discourse structure (which narrates the event once) and story structure (in which the event potentially happens on numerous occasions) has already emerged, in the form of iterative narrative.Genette defines the iterative narrative thus: “This type of narrative, where a single narrative utterance takes upon itself several occurrences together (once again several events considered only in terms of their analogy), we will call iterative narrative” (1980 [1972]: 116). However, the readerly act of moving the pebble and engaging in doubly deictic subjectivity alters the narrative frequency, moving it closer to a singulative narrative whereby there is a correspondence between the number of times an event actually happens in the story and the number of times an event is narrated in the discourse. (Notably, the reader is most likely to carry this act of throwing the pebble at least one further time, and even this does not account for reading TOC in more than one sitting). Due to the interactive capacities of the new media novel, story is being matched against a combination of discourse and process (and of course the structure of the discourse is what allows, enables, and constrains process). Consequently, doubly deictic subjectivity suggests an additional layer in the understanding of narrative time. In this episode from TOC, process time effectively overrides discourse time; certainly, it renders discourse time less significant. The process time created by the reader’s interaction enhances doubly deictic subjectivity by creating a frequency equivalence with story time.

Material Time vs. New Media Time

You decide to vote for Chronos and so cast your pebble into the box with a simple move of the cursor. On doing so, the lid to the box slides off, revealing what resembles piano paper roll – essentially perforated paper, the punched holes directing the piano to play whatever tune has been coded into it automatically – and an index marker which moves along the roll, playing music. In the bell jar, an animation begins. Moving your cursor over the bell jar, it changes to a magnifying glass; clicking then enlarges the image allowing you to watch the animation in full screen view.

The “TOC” animation is in black and white, its imagery centring around clocks, and their moving parts. A female voice opens the narration: “Upon a time, in a tense that marked the reader’s comfortable distance from it, a calamity befell the good people of X.” Stylistically, the sentence performs its own meaning. Written in past tense, it is an example of indirect discourse. Moreover, the third-person reference to the reader has two key effects. Firstly, since you are the reader, it works to alienate you from the narrative, a deliberate strategy which leads to the second effect, creating and thus legitimising the “comfortable distance” to which the narrator refers.

Interestingly, the “TOC” animation started its life in material rather than new media form. It was originally published as a text-only piece in Literal Latté, a New York based journal of poetry, prose and art founded in 1994. In 1996, it was published in Black Ice as text but with facing pages of art, and later the same year in issue 37 of Émigré, an art and design magazine, it was featured as a fully integrated multimodal combination of word and image. Later, spreads from Émigré were hung as a mobius strip from the ceiling in an exhibit at The Center for Book and Paper Arts in Chicago, which included a special reading by Tomasula and his wife Maria Tomasula (whose voice is on the narration of TOC and who also illustrated the island sections) while images were projected on a screen behind them.I have been unable to locate the texts from Literal Latté and Black Ice since the online archives for both do not go back far enough. My source in this is Steve Tomasula from a personal correspondence, as is also the case with my awareness of the exhibition at The Center for Book and Paper Arts. Personal Correspondence. May 2010. Email.In its evolution from text-only format through to the digital animation featured in TOC the new media novel, there is a clear increase in multimodality. Indeed, as Tomasula himself says, “this was sort of the genesis of TOC as a multimedia piece” (personal correspondence). Since different media offer different affordances for interaction, this presents a unique opportunity to note the distinct effects and reader experiences granted by the text in various forms. In this section of the paper, I will discuss such differences, concentrating on TOC, the printed multimodal version from Émigré magazine, and the TOC animation from TOC the new media novel.

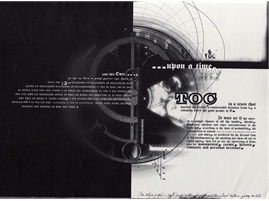

The opening sentence to the narration just discussed presents a suitable opportunity for media comparison. The images below show the opening page from the Émigré “TOC” and a screenshot from the “TOC” Animation taken approximately as the reader is mentioned.

Figure 4: Comparison between Émigré “TOC” (left) and “TOC” Animation (right) for “Upon a time, in a tense that marked the reader’s comfortable distance from it, a calamity befell the good people of X”

As can be seen, these are startlingly different images (though of course as the “TOC” Animation progresses its filmic images display a clear kinship with those from its Émigré magazine counterpart). In Émigré “TOC,” the page is divided down the middle (black to the left, white to the right), and a clock’s inner workings are at the center. In this early point of the “TOC” Animation, however, you are looking at a ‘mostly white image, the image moving along thin black lines. While the lack of detail in the animation at this point directs greater attention to the narrator’s words, the printed Émigré “TOC” representation of the opening sentence seems more powerful. Not only is the image more remarkable, but your interaction with the text maps more easily onto the apostrophic ‘reader’ role that is linguistically referenced. In Émigré “TOC,” you are literally reading, while in the “TOC” Animation, you are viewing and listening.

As the text progresses, both versions can be seen as having media-specific successes and failures. The narrator continues:

It was as if the one-in-a-googol chance of all the iambs, throbs, arhythmic rhythms, and other contradictions of the heart had, according to the laws of probability, hit a single beat in unison. That is to say, the present had come to pass. And when, as predicted by the second law of thermodynamics, the upswing put them all out of synch again, they felt as one the shattering of Time into its monumental, cosmic, historic, romantic and personal versions.

While the narration evidently continues the meditation on time and subjective experience, I want to focus on the final sentence, and in particular the phrase, “they felt as one the shattering of Time.” In the “TOC” Animation, as the words “they felt as one” are spoken, the word TOC emerges from the depths of the image. Seconds later, as the word “shattering” is spoken, the image shakes violently. When it returns to focus, the screen is cracked (shattered) and the word TIC can be seen briefly before it quickly fades. The animation now clearly resembles the Émigré “TOC” layout, yet, the print equivalent cannot produce the same effects. The “TOC” image here resembles the first page of the Émigré “TOC,” while for readers of the printed counterpart to see the TIC image, they must turn the page where it is of course accompanied by further written text.

Figure 5: Successive Screenshots from the “TOC” Animation: “TOC” & “TIC”

The “TOC” animation is utilising multimediality to create the multisensory. The word “shattered” is spoken simultaneously as the camera shakes and the image shatters giving the impression of broken glass. In cognitive science (Bertelsen and de Gelder 2004; Gibbons 2010a), it has been shown that when any given perceived event is the consequence of a co-occurrence of two or more modalities, it results in enhanced neurological response. Because the filmic medium is able to combine a greater number of sensory modalities (in this example from TOC, aural, verbal, visual, and perceived motion are all involved), the narrative episode seems more intense. Moreover, the broken glass can be seen as “remediating,” in Bolter and Gruisin’s (1999) terms, the computer screen itself. As such, the “TOC” animation is able to create a greater sense of temporal immediacy for the viewer, and this immediacy, its compelling nature, stems from its multimodality.

The length of both the animation and the Émigré “TOC” would allow for a much extended discussion. Since this paper looks at TOC from a more holistic perspective, such sustained attention is beyond its scope. Nevertheless, I’d like to look at one further example – the conclusion to both the Émigré “TOC” and the “TOC” animation. The Émigré “TOC” is printed on trifold foldout pages. The narrative starts on the right hand side of the first page and continues on the right hand side until, you reach what seems like the last page, at which point the text changes direction revolving around the central clock. You then have to rotate the magazine and read the other side of every page returning you to the page on which the narrative began. Obviously, this is in contrast to the “TOC” animation. In the animation, the image on the screen has likewise revolved so that the black half is now on the right hand side, but there is no physical interaction. The narrative conclusion to both is:

and she longed for a way to approximate the sense of a whole that was much easier to fake in art than in life, a transformation of narrative repetition as death into repetition of narrative as perpetual – O! she cried, if only she could find a way to do it

just this once…

In the “TOC” animation, the narrator then begins speaking the opening lines so that the final line joins with the opening sentence: “just this once … / …Upon a time …” A comparable effect is created in the Émigré “TOC”: the final line “just this once …” is placed upside-down in relation to the preceding text, its directionality thus matching the opening ”… Upon a time.” Thus the reader must rotate the magazine again to read the final sentence with the ellipsis suggesting narrative continuation. Now, in the “TOC” animation, the spoken narration soon fades out. However, the durability of the Émigré “TOC” means that ultimately, should readers make the unlikely choice to continue, reading the Émigré “TOC” could be an infinite activity, more accurately achieving the idea of the “transformation of narrative repetition as death into repetition of narrative as perpetual.” A novel that similarly plays with time and rotation in reading is Mark Z. Danielewski’s Only Revolutions (2006) which presents a contemporary take on the “dos-a-dos” format, meaning that the narrative is read from both sides, and continually rotated. Interestingly, in discussion of Only Revolutions, critics (see Bray forthcoming 2010; Hansen forthcoming 2010; Hayles forthcoming 2010) have argued that organising the creative potentialities of the book medium in this way creates a “dynamic of renewal” (Hayles forthcoming 2010). Such a dynamic of renewal, of perpetual narrativity, cannot be replicated in new media form, at least not in the same way.

In terms of temporality, it is clear that printed multimodal texts and multimedial animation engender temporal experience in different ways. The printed Émigré “TOC” uses the reader’s interaction to imitate the ticking of a clock - your physical reading journey is clockwise and like clock-time is cyclical and continuous. The “TOC” animation in comparison harnesses simultaneity and remediation to engender more immediate experience.

Perceived Time

After the “TOC” animation, you are returned to the navigation screen, so you decide to pick up the pebble again, this time putting it in the Logos box. Again, the box opens and again contains piano paper roll, only this time instead of an index marker moving along the roll, the roll itself is moving and the computer mouse controls a target pointer (created by a horizontal line and vertical line that intersect) which you can move around the box. As the music plays, the holes move from right to left, and you notice that some are brighter colours than others – there are some lines which are more intense shades of blue, green, and red. As you discover, aiming your target and clicking on the brighter lines opens parts of the narrative: Click on a green hole and you are provided, within the navigation screen, with distances to the sun from other planetary systems; click on a blue hole and you unlock text pieces – the scroll stories which open in the bell jar for you to read; click on red holes and you bring up video clips which are part of the Zoe Beloff animations. While the scrolls present self-contained fables, the videos are deeply and disturbingly ambiguous. As a reader, you are required to infer the temporal relations and narrative connections between these fables and videos for yourself.

Figure 6: Screenshot of the Navigation Page for TOC, having unlocked Logos sections.

The Logos box, therefore, demands a much greater degree of interactivity from you than the Chronos box. However, as with the “TOC” animation, this cannot be rushed. The piano paper roll moves at its own speed and you have no control over when each coloured hole appears or how quickly. This waiting game does have experiential costs: it can be frustrating for readers. The wait, however, is important in itself, particularly in terms of the connections between HCI and temporal experience.

Time perception is always relative and always subjective – the stimuli received by your brain enables you to construct a representation of time, and as such different stimuli can create temporal distortions. Eagleman (2008) provides a succinct précis of recent work in neuroscience on the connections between visual processing and perceived time, and in particular duration distortion. Summarising the development of the twentieth century understanding of perceived time judgements (see Brown 1931; Brown 1995; Roelofs and Zeeman 1951; Schiffman and Bobko 1974), Eagleman highlights three central factors: (1) motion, (2) sequence complexity, and (3) event density (the number of events). Event density is important because “the occurrence of many events is interpreted by the brain as a longer duration” (Eagleman 131). Moreover, by using flickering visual displays, Kanai et al. (2006) show that while motion contributes to the perception of longer duration, the primary determinant is temporal duration. In addition, repetition and deviation also contribute to temporal perception: “When a stimulus is shown repeatedly, the first appearance is judged to have a longer duration than successive stimuli. Similarly, an ‘oddball’ stimulus in a repeated series will also be judged to have lasted longer than others of equal duration” (Eagleman 132). Such perceived longer duration is known as the subjective expansion of time, while we can refer to a perceived shorter duration as the subjective contraction of time.

The psychological research on perceived time has noteworthy implications for your temporal experience as you interact with the Logos box in TOC. The piano roll is certainly in motion, and the coloured holes that you must click on appear from the right and move leftward. Although there is a certain predictability to the holes (which we might say constitute “events”), exactly when and where on the piano roll they appear is unfixed. Thus, there is an unpredictability, an oddball-ness, to each and every hole, within a pattern of sorts. Relating this to the psychological research on perceived time, we can infer that the Logos box is likely to evoke a subjective expansion of time for the reader-user. Such an expansion of time is even more likely when we consider the disruptions to the sequence in the form of the story scrolls and the Zoe Beloff animations (another form of event), as well as the self-awareness brought about by the reader-user’s interactivity.

The Logos box of TOC effectively foregrounds your experience of time. The “TOC” animation unlocked by the Chronos box allows for inactivity and immersive viewing which reduces awareness of time passing. In contrast, time is felt and perceived in your interactions with the Logos box. Interestingly, then, TOC utilises its new media design and HCI in order to create different temporal experiences, subjective contractions and expansions of time, in the narrative’s process time. While earlier when working with doubly deictic subjectivity, process disrupts the traditional model of narrative frequency, here it distorts duration. As such, two of the fundamental categories of narrative time are unsettled somewhat by the kinds of interaction that TOC, as a new media novel, encourages.

The Logic of Chronology: A Conclusion

The differing experiences offered by the Chronos box and the Logos box can be linked to the character’s names. Chronos is a well known Greek god of time, and thus it seems apt that his box was a filmic animation that meditated on the nature of time. Logos on the other hand relates in philosophy to logic, order, and rhetoric. Thus it similarly seems apt that encountering these narrative segments require the reader to deduce how they are connected – to order them and derive some narrative logic from them. Tomasula characterises Chronos and Logos in the following way:

Chronos always wanted to lead, for he was certain that he knew what was what and in what order things came though he couldn’t say so without Logos’ help. For his part, Logos delighted in making all Chronos said slippery as soap and as a transient as a bubble, though it soon became apparent that neither slips nor bubbles were possible without Chronos’ gravity.

Just as in the relationship of the two brothers, narrativity itself requires both Chronos and Logos: temporality, order and skilful delivery. TOC is undoubtedly about time, both thematically and rhematically.

Hayles (2008) suggests that there are four main characteristics of the digital text:

- It is layered.

- It tends to be multimodal.

- It separates storage (code and file location) from performance.

- It manifests fractured temporality.

TOC embodies all of these characteristics, though undoubtedly fractured temporality is most resonant. Through its subject matter (story), narrative organisation (discourse), and demands for readerly interaction (process), TOC playfully manipulates the experience of perceived time. Hayles notes that “perceived time is emergent rather than given, constantly modulating according to which processes and locations are dominant at a given instant” (2008: 80), and this is poignantly felt in reading TOC. Precisely because time is perpetual, cyclical, and deeply personal, I want to end this essay where I began: “You’ve never experienced a novel like this.”

Works Cited

Augustine, Saint (Bishop of Hippo). Confessions of Augustine: An Electronic Edition. Text and Commentary by James J. O’Donnell. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1992 [386-430]. Print. Online version The Confessions of Augustine: An Electronic Edition, Web. http://www.stoa.org/hippo/ Bell, Alice, Astrid Ensslin, Dave Ciccoricco, Hans Rustad, Jess Laccetti, and Jessica Pressman. “A [S]creed for Digital Fiction.” Electronic Book Review. 2010. Web. Beloff, Zoe. The Influencing Machine of Miss Natalija A. Interactive Video Installation, 2001. Web. http://www.zoebeloff.com/influencing/ Benford, Steve and Gabriella Giannachi. “Temporal Trajectories in Shared Interactive Narratives.” Proceedings of the twenty-sixth annual SIGCHI conference on Human factors in computing systems*.* 2008. Web. http://www.mrl.nott.ac.uk/~sdb/research/downloadable%20papers/temporal-trajectories-dl.pdf

Bertelsen, Paul and de Gelder, Beatrice. “The psychology of multimodal perception.” Crossmodal Space and Crossmodal Action. Eds. Charles Spense and Jon Driver. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press, 2004. 141-117

Black Ice. Literary Magazine. Web. http://www.altx.com/profiles/ Bolter, Jay David and Richard Gruisin. Remediation: Understanding New Media. Cambridge: MIT Press, 1999. Bray, Joe. “Only Revolutions and the Drug of Rereading.” Mark Z. Danielewski. Eds. Joe Bray and Alison Gibbons. Manchester: Manchester University Press, forthcoming 2010. Print.

Brown, J. F. “Motion expands perceived time: On time perception in visual movement fields.” Psychological Research 14.1, 1931. 233-248. Print.

Brown, S. W. “Time, change, and motion: The effects of stimulus movement on temporal perception.” Perceptual Psychophysics 57, 1995: 105-116. Print.

Carstensen, Kai-Uwe. “Spatio-temporal ontologies and attention.” Spatial Cognition and Computation 7.1, 2007. 13-32. Print. Ensslin, Astrid. “Respiratory Narrative: Multimodality and Cybernetic Corporeality in ‘Physio-Cybertext.’” New Perspectives on Narrative and Multimodality. Ed. Ruth Page. London; New York: Routledge, 2010. 155-165. Print. Genette, Gerard. Paratexts: Thresholds of Interpretation. Trans. Jane E. Lewin. Foreward. Richard Macksey. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997 [1987]. Print. Genette, Gerard. Narrative Discourse. Trans. Jane E. Lewin. Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1980 [1972]. Print.

Gibbons, Alison. Towards a Multimodal Cognitive Poetics: Three Literary Case Studies. Doctoral Thesis. University of Sheffield, 2008. Print.

Gibbons, Alison. “‘I Contain Multitudes’: Narrative Multimodality and the Book that Bleeds.” New Perspectives on Narrative and Multimodality. Ed. Ruth Page. London; New York: Routledge, 2010. 99-114. Print.

Gibbons, Alison. “Narrative worlds and multimodal figures in House of Leaves: ‘-find your own words; I have no more.’” Intermediality and Storytelling. Eds. Marina Grishakova and Marie-Laure Ryan. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, forthcoming 2010a. Print.

Gibbons, Alison. Multimodality, Cognition, and Experimental Literature. London; New York: Routledge, forthcoming 2010b. Print.

Hansen, Mark B. N. “Print Interface to Time: Only Revolutions at the Crossroads of Narrative and History.” Mark Z. Danielewski. Eds. Joe Bray and Alison Gibbons. Manchester: Manchester University Press, forthcoming 2010. Print. Hayles, N. Katherine. Electronic Literature. New Horizons for the Literary. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame, 2008. Print. Hayles, N. Katherine. “Mapping Time, charting data: the spatial aesthetic of Mark Z. Danielewski’s Only Revolutions.” Mark Z. Danielewski. Eds. Joe Bray and Alison Gibbons. Manchester: Manchester University Press, forthcoming 2010. Print. Herman, David. “Textual You and Double Deixis in Edna O’Brien’s A Pagan Place.” Style 28.3, 1994. 378-410. Print. Herman, David. Story Logic: Problems and Possibilities of Narrative. Lincoln, NB; London: University of Nebraska Press, 2001. Print.

Isham, Christopher J. and Konstantina N. Savvidou. “Time and Modern Physics.” Time. Ed. Katkinka Ridderbos, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002. 6-26. Print.

Kanai, Ryota, Chris L. E. Paffen, Hinze Hogendoorn and Frans A. J. Verstraten. “Time dilation in dynamic visual display.” Journal of Vision 6, 2006. 1421-1430. Print.

Literal Latté: Journal of Poetry, Prose, and Art. Web. http://www.literal-latte.com/

Morrissey, Judd. The Jew’s Daughter. Online Hypertext. Web. http://www.thejewsdaughter.com/

Nørgaard, Nina. “The Semiotics of Typography in Literary Texts: A multimodal approach.” Orbis Litterarum 64.2, 2009. 141-160. Print.

Ridderbos, Katkinka. “Introduction.” Time. Ed. Katkinka Ridderbos, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002. 1-5. Print.

Roelofs, C. O. Z. and W. P. C. Zeeman. “Influence of different sequences of optical stimulus on the estimation of duration of a given interval of time.” Acta Psychologica 8, 1951. 89-128. Print.

Ryan, Marie-Laure. Narrative as Virtual Reality: Immersion and Interactivity in Literature and Electronic Media, Baltimore; London: John Hopkins University Press, 2001. Print.

Schiffman, H. R. and Douglas J, Bobko. “Effects of stimulus complexity on the perception of brief temporal intervals.” Journal of Experimental Psychology 103.1, 1974. 156-159. Print.

Stockwell, Peter. Texture: A Cognitive Aesthetics of Reading. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2009. Print.

van Leeuwen, Theo. “Typographic Meaning.” Visual Communication 4.2, 2005. 137-143. Print.

van Leeuwen, Theo. “Towards a semiotics of typography.” Information Design Journal & Document Design 14.2, 2006. 139-155. Print.

Vaupotič, Aleš and Narvika Bovcon. “Space and Time in New Media Objects – VideoSpace, Friedhof Laguna, Mouseion Serapeion, S.O.L.A.R.I.S., To Brecknock …, Data Dune.” ELMAR 2008 – 50th International Symposium, Volume 1, 2008. Web. http://ieeexplore.ieee.org/stamp/stamp.jsp?arnumber=04747553

Cite this essay

Gibbons, Alison. "“You’ve never experienced a novel like this”: Time and Interaction when reading TOC" electronic book review, 28 June 2012, https://electronicbookreview.com/publications/youve-never-experienced-a-novel-like-this-time-and-interaction-when-reading-toc/