Taking his cue from the first line of Lady Mary Wroth’s 17th Century sonnet sequence, “In this strange labyrinth how shall I turn?” Corey Sparks locates readers in a contemporary, procedural sonnet at the intersection of electronic literature, digital edition creation, gaming, and literary poetics. Sparks includes a photo of a reconstructed medieval labyrinth, taken at St. Fin Barre's Cathedral in Cork, Ireland during his attendance at the 2019 Electronic Literature Organization conference.

“If you are afraid,” remarks Richard Klein, “that by reading you might add something of yourself to the text, you will not begin to read at all” (922). Klein emphatically articulates the familiar position that the encounter between text and reader is participatory, inventive, and dynamic. Such a characterization of text-reader interpretive relations attends accounts of what Stephanie Strickland calls “this new reading-condition” of the “born digital” text. Key to the interpretive dimensions of this “new reading-condition” is a sense of ability; it is a sense in which, as Serge Bouchardon and Davin Heckman argue, “The digital text is as much a manipulable text as a readable text” (“Digital Manipulability”). The “adding something of yourself” of reading moves from fraught metaphysical possibility to being the necessary means by which a reader becomes entangled with the digital text-object. To accounts of text-reader relations that differentiate the interpretive reader-text dynamic as it exists in print or in digital scenes of interpretation I want to add the concept of “deformance.” This portmanteau of “deform” and “performance” is, I argue, a crucial means of approaching questions of meaning and interpretation. Lisa Samuels and Jerome McGann give the name “deformance” to an interpretive activity that mirrors the accounts above; an activity in which “meaning is more a dynamic exchange than a discoverable content” (31). Samuels and McGann provide the example of reading a poem backwards as a deformative procedure that opens possibilities of meaning. Significantly, however, deformance entails “not a re-imagined meaning but a project for reconstituting [a] work’s aesthetic form” (28). Deformance explores a text’s interpretive dynamics via experimentation with its formal properties.

The above sketch of recent accounts of reader-text relations traces a dynamic in which the interpretive entanglements of reader and text are haunted by a residue of fear, by the risk of failure. In this essay I seek to concenter a sense of fearfulness in order to reorient characterizations of the digital reading-condition away from assumptions of mastery toward risk, doubt, and fragmentation. “Deformance” as a concept, I argue, is particularly suited to register this haunted dynamic. Risk is fundamental to Espen Aarseth’s account of ergodic literature, a concept more often referenced for its exploration of textual play than for readerly fear. Ergodic literature is defined as literature that requires a playful “non-trivial” effort to traverse; Aarseth says, though, that the ergodic text “puts its would-be reader at risk: the risk of rejection” (4). Strickland, evoking a seemingly thorough-going self-surveillance, argues that the reader of the digital text “must…become a metareader, reading her reading, her reaction to this new reading-condition.” For Mark Sample, “deformance” should be understood through the frisson of “deformity” since a deformative procedure should, he argues, refuse to “reestablish the integrity of a text.” Less about unlocking the meaning of a text, deformance is instead, I want to emphasize, the risky opportunity for both reader and text to change and be changed.

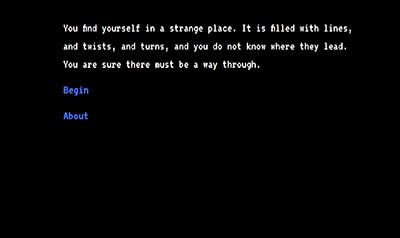

In order to explicate deformance as a productive means of approaching questions of meaning and interpretation that traverse the usual print-digital divides, I describe and contextualize the development of a literary gaming project called “The Procedural Sonnet.” This project, located at the intersection of electronic literature, digital edition creation, gaming, and literary poetics seeks to connect premodern literary forms with contemporary digital platforms. The project uses the hypertext game platform Twine to “deform” a section of Mary Wroth’s seventeenth-century sonnet sequence, Pamphilia to Amphilanthus. Wroth’s sequence allows me to do two things: first, work with what is arguably the most recognizable lyric form in the English language; and second, think with a writer invested in deforming the gendered complexities of that lyric form. Finally, my engagement with the sonnet form in the project “deforms” the procedures of the narrative-oriented Twine platform.

The Procedural Sonnet project uses Twine—a hyperlink game platform—to allow players to “play,” depending on the game “level,” a single English sonnet or a longer sonnet sequence. In an initial version of the game each game lexia presents players with a line of William Shakespeare’s first sonnet.

Each line includes one or more bolded words, and players navigate through the sonnet by clicking on the bolded words. Depending on which word is chosen, players might proceed through the sonnet line by line. One might also skip lines or loop back. In this initial version, the game’s conclusion displays a player’s “edition” of the poetry: each chosen line of the sonnet is displayed; any line skipped while playing is omitted.

In this version the player is presented with a limited number of choices. The effects of these choices are unknown. That is, there is no necessary indicator of what may happen when one chooses to click on one bolded word versus another bolded word. It is only at the conclusion of the game where the player’s choices are retrospectively displayed. The game provides no clue as to what the outcome of the choice will be other than another line of the poem; this is not unlike Michael Joyce’s afternoon: a story, which “does not give its reader any idea of what words are specifically linked to another outcome” (Moulthrop). In The Procedural Sonnet a player may choose one word over another for reasons haunted by the act of “adding something of yourself” to the text—certain conceptual preferences or curiosities, word euphonies or dissonances.

A current revision of the game expands on this original idea, but it also takes new turns. First, it turns from a single sonnet to an entire corona, or “crown,” of sonnets. A corona is a 14-poem sequence in which the final line of one sonnet becomes the first line of the following poem. Shifting from a single sonnet to a corona emphasizes the embeddedness of the sonnet form in larger narrative networks over and against an assumed isolation of the lyric utterance. Second, the revision turns from Shakespeare to Lady Mary Wroth, who includes a crown of sonnets in her seventeenth-century sonnet sequence Pamphilia to Amphilanthus. I have turned to Wroth because she is a fascinating figure in literary history and because her corona performs compelling—one might argue even deformative—work on the form. About Wroth’s texts biographer Margaret P. Hannay says, “they function more like a kaleidoscope than a mirror,” refracting literary and courtly impulses of seventeenth-century England (xii).

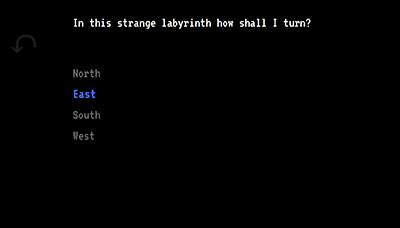

Moreover, the revision explicitly spatializes the sonnet form by taking as its cue the first line of Wroth’s corona, “In this strange labyrinth how shall I turn?” In response to this first line, the sequence becomes a text adventure game.

The lines of the sonnets have been mapped onto a labyrinth, with each line of the sequence constituting a “passage” or even “room.” Now, rather than having bolded words to choose from, players are presented with a line of poetry followed by a list of the cardinal directions by which to proceed through the corona. To represent the difference between closed and open passages between passages, the cardinal directions are either hyperlinks or greyed out to mark their unavailability.

The exit always remains in one place, and at least one route through the labyrinth remains open; player choices often shift the routes. A choice to go North rather than East at some point opens a door or seals a wall, so to speak, elsewhere. The player often does not know such an event has happened, and the only way to figure out the location of such effects would be to map out multiple playthroughs. The reward of doing such work is one of a literary nature: not only to “find” more parts of the sonnet crown but also to locate more and different connections within and across the sonnets.

This experience of navigating an unfamiliar space via text that is at turns inscrutable or directive captures the spirit of early text adventures. The player’s interaction was rooted in words, a participatory dynamic often characterized by “the loaded phrases of a poetic style” (Salter 29). Impressionistic description and subtle word puzzles more often than not marked a player’s experience of early games like Colossal Cave Adventure. Traversing a text-based game also tends to ask the player to supplement her interaction with the game environment. For example, Adventure, with its labyrinthine cavern system, prompted players to create and maintain their own maps of the game world in order to keep track of their progress through the caves. Tracy Kidder notes a description of a player who had drawn “dozens” maps of the game’s layout (qtd in Montfort 92). According to Nick Montfort, “making such maps was an essential part of solving Adventure and would remain essential to interacting with most other works” (92). Such player map-making might be understood as a spatio-visual deformance of an ambiguous text-based game world, as the game text prompted players to create attendant supplementary-yet-necessary visual and textual descriptions.

In the case of The Procedural Sonnet, Wroth’s corona deforms into a text adventure game, requiring that the player navigate via textual input a seemingly inscrutable game world solely constituted of textual fragments. An element of textual fragmentariness puts at risk the player’s sense of textual possibility. There is a “captivating ambiguity” to Adventure, argues Alenda Y. Chang; in fact, “the most cited areas of the game seem to be its two labyrinths, which owe much of their lasting impression to their rendering in words” (67). The Procedural Sonnet game environment similarly invites exploration even as it presents a pre-determined set of navigation choices.

Deforming Wroth’s corona into a text adventure game is a mode of reading the sonnets, highlighting latent interpretive possibilities. In her sequence, Wroth contemplates the pursuit of love across erotic, spiritual, political registers. She concludes the first sonnet of the sequence by staging a near-paralysis in the face of the fact that choices must be made:

Thus let me take the right, or left hand way;

Go forward, or stand still, or back retire;

I must these doubts endure without allay

Or help, but travail find for my best hire;

Yet that which most my troubled sense doth move

Is to leave all, and take the thread of love. (“Crown 1,” lines 9–14)

Entry into the labyrinth is suffused with doubt. One’s “troubled sense” may suggest the best course of action “is to leave all.” The necessary procedure, however, requires a kind of Kleinian setting aside of fears; the more difficult path requires embracing one’s doubtful position—“I must these doubts endure.” The pursuit of what Wroth calls “the thread of love,” alluding to the Minoan labyrinth of Greek mythology, is not an abandonment of doubt but a reinvestment in navigating ambiguous poetic paths.

This brief explication of an early moment in Wroth’s corona highlights the ways deformance emerges from and generates textual interpretation. The Procedural Sonnet does not just ask—to adapt questions posed by Samuels and McGann—“what does the corona mean?” Rather, the game asks, “how do we release or expose the corona’s formal possibilities of meaning?” The game’s deformance-work concerns not just what Wroth’s poems say but what it means to try to make one’s way through a lyric poem. Articulated slightly differently: by what procedures might one read a sonnet or a whole sequence of sonnets? In The Procedural Sonnet, the corona becomes a space for movement, for taking “the right, or the left hand way” despite one’s doubts. Each line of each poem becomes a location to which or through which the player travels. The order of that travel is, moreover, explicitly non-linear. The player cannot follow poetic lines according to the traditional logic of the sonnet form.

The sonnet’s form in English literary traditions is most commonly—with some rhyme scheme variation—fourteen lines of iambic pentameter divided into three quatrains and a closing couplet. Most fundamentally, the sonnet form suggests issues of proportion, development and iteration, and conclusion or contradiction. “State it; dance it. Or—state it; dance the undoing of it” (Hass 122). With the sonnet’s relatively closed form, Michael R. G. Spiller argues, “the poem itself ends at a point not controlled by the author’s will” (2). For Spiller, the end of the poem comes for the writer as an inevitability. As Robert Hass notes, however, there are many examples of rather sonnet-ish poems that are 11, 15, 18 and even more lines. Hass understands formal lyric poetry to be centered on impulses rather than constraining rules, a position that invites examination of formal experimentation rather than attention to poetic conformity. In The Procedural Sonnet game, though, the labyrinth’s walls emerge as gaps in Wroth’s text. Such gaps are actually quite fitting, as Wroth’s sonnets possess, Paul J. Hecht argues, “an aesthetic that eschews a sense of formal ‘mastery,’” one that “includes syntactic breaks as a sort of sonic and informational distortion” (92).

One might again nod to Aarseth and say the game renders explicit an ergodic potential of Wroth’s sonnets. That is, there is always the potential to playfully and non-trivially read around in a poem. In fact, the development of an interpretation demands that the reader move not linearly but between and among various words, sounds, lines, rhythms—what Caroline Levine calls the “arrangement and control of materials” in a lyric poem (74). What better form with which to think about the complicated nature of poetic arrangement and control than the labyrinth? That evocative space about which Borges said, “No one realized that the book and the labyrinth were one and the same.”

Even as there is an entrance and an exit, an ostensible beginning and terminus that suggest narrative progression, The Procedural Sonnet is less concerned with achieving ends; it is more invested in a labyrinthine deformation of the narrative impulse of text adventures. Twine, as a platform, tends to operate by presenting a player with several options from which to choose within a narrative marked by arborescent branching potential outcomes. This procedure gestures back toward early hypertext works; Twine-creator Chris Klimas understands such works to be the platform’s “broader context.” Twine-based games such as Zoe Quinn’s Depression Quest, and Kris Ligman’s You Are Jeff Bezos present the player with a narrative and choices among several options for progressing the narrative. As choices are made, the narrative shifts in different directions. In Quinn’s game, the player either slowly begins to address and manage her depressed condition or gets worse; in Ligman’s game, the player attempts to spend as much of Jeff Bezos’ wealth as possible before getting arrested.

Wroth’s sonnet crown deforms such narrative procedures toward a poetic labyrinth. In this deformance, playful alteration not of literary content but procedure takes center stage. The labyrinth disturbs an “anticipation of endings” (Douglas 184). Traditionally speaking, a labyrinth is not the same as a maze. A labyrinth presents the traverser with a particular winding route, as seen in this reconstruction of a medieval labyrinth.

The labyrinth possesses one entrance/exit and a single path that leads to a central spot, and the same path leads back out. This kind of labyrinth is often associated with religious meditation. Conversely, a maze presents the traverser with myriad possible routes, some of which mislead the traverser, making it possible that one could become lost. Now, these distinctions are often blurred, as we can see from Wroth’s depiction of a labyrinth where one could become lost (both literally and metaphorically speaking). The labyrinthine procedure of The Procedural Sonnet disrupts a focus on narrative, and instead directs it toward the fortuitous connection or collision of poetic lines. The player is not traversing a narrative toward some goal but instead lyrically wandering, not merely following a thread of love but generating her own.

Works Cited

Aarseth, Espen. Cybertext: Perspectives on Ergodic Literature. Johns Hopkins University Press, 1997.

Bourchardon, Serge, and Davin Heckman. “Digital Manipulability and Digital Literature.” Electronic Book Review. 5 August 2012. http://electronicbookreview.com/essay/digital-manipulability-and-digital-literature/

Chang, Alenda Y. “Games as Environmental Texts.” Qui Parle, vol. 19, no. 2, 2011, pp. 56–84. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/10.5250/quiparle.19.2.0057.

Douglas, J. Yellowlees. “’How Do I Stop This Thing?’: Closure and Indeterminacy in Interactive Narratives.” Hyper/text/theory, edited by George P. Landow. Johns Hopkins University Press, 1994, pp. 159–88.

Hannay, Margaret P. Mary Sidney, Lady Wroth. Ashgate Publishing, 2010.

Hass, Robert. A Little Book on Form: An Exploration into the Formal Imagination of Poetry. Ecco, 2017.

Hecht, Paul J. “Distortion, Aggression, and Sex in Mary Wroth’s Sonnets.” SEL Studies in English Literature 1500-1900, vol. 53, no. 1, 2013, pp. 91–115. Project MUSE, doi:10.1353/sel.2013.0000.

Klein, Richard. “The Future of Literary Criticism,” Literary Criticism for the Twenty-First Century, special issue of PMLA, vol. 125, no. 4, 2010, pp. 920–23. ProjectMuse.

Klimas, Chris. “Twine: Past, Present, Future.” chrisklimas.com. 21 June 2019. https://chrisklimas.com/twine-past-present-future/.

Levine, Caroline. Forms: Whole, Hierarchy, Network. Princeton University Press, 2015.

Ligman, Chris. You Are Jeff Bezos. 2018. https://direkris.itch.io/you-are-jeff-bezos.

Montfort, Nick. Twisty Little Passages: An Approach to Interactive Fiction. MIT University Press, 2003.

Moulthrop, Stuart. “Stuart Moulthrop Traversal, part 1.” Pathfinders by Dene Grigar. 9 July 2013. https://vimeo.com/115154109.

Quinn, Zoe. Depression Quest: An Interactive (non)fiction About Living with Depression. 2013. http://www.depressionquest.com/dqfinal.html.

Salter, Anastasia. What is Your Quest? From Adventure Games to Interactive Books. University of Iowa Press, 2014.

Sample, Mark. “Notes Towards a Deformed Humanities.” @samplereality.com. 2 May 2012. http://www.samplereality.com/2012/05/02/notes-towards-a-deformed-humanities/.

Samuels, Lisa and Jerome McGann. “Deformance and Interpretation.” Poetry & Poetics, special issue of New Literary History, vol. 30, no. 1, 1999, pp. 25–56.

Spiller, Michael R. G. The Development of the Sonnet: An Introduction. Routledge, 1992. ProQuest EBook Central. https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/csuchico/detail.action?docID=179371.

Strickland, Stephanie. “Born Digital.” poetryfoundation.org. 13 February 2009. https://www.poetryfoundation.org/articles/69224/born-digital.

Wroth, Mary. Pamphilia to Amphilanthus. “Folger Modernisation.” Edited by Paul Salzman, Tony Allan, Gayle Allan, and Jo Allan. Mary Wroth’s Poetry: An Electronic Edition. http://wroth.latrobe.edu.au/all-poems.html.