A conversation at a heightened level of intensity, ranging from the aleatory tradition of Emmett Williams, Jackson Mac Low, and John Cage, through post-Poundian poetry and its Chinese influences, kinetic poetry or programmable media where the poem itself is performing, not just the poet. Attention is also given to the Internet as these two literary artists knew it for a very brief moment, before Google and Facebook, circa 2004, "figured out that everybody needed an account."

Scott Rettberg and John Cayley in conversation at the John D. Rockefeller Library, Brown University, Providence, Rhode Island. December 04, 2019. John Cayley is Professor of Literary Arts at Brown. Cayley is a pioneering digital poet, who began experimenting with using algorithms coded for personal computers in his poetic practice during the late 1970s. He was winner of the 2001 Electronic Literature Award for Digital Poetry and the Electronic Literature Organization's 2018 Marjorie C. Luesebrink Career Achievement Award. His book Grammalepsy: Essays on Digital Language Art, was published by Bloomsbury Academic in 2018. Scott Rettberg is Professor of Digital Culture at the University of Bergen and the author of Electronic Literature (Polity, 2018).

Scott Rettberg

John, I thought it'd be interesting to start out by asking about your early career a bit. You were trained as a Sinologist weren't you, or self-trained?

John Cayley

No, I went to university.

Scott Rettberg

How did that lead into your early digital writing practices?

John Cayley

Well what happened was that I was doing postgraduate work in Classical Chinese literature and my supervisor, who was a very accomplished linguist in the sense that, he didn't have an investment in linguistic theory, but his practical linguistics was unparalleled. He got interested in the problem of representing Chinese text properly within computation, early computation at the time. Personal computers had begun to appear in 1978 or so, maybe a little later than that. He had already been encoding Chinese for mainframes at the university and started playing with personal computers, and becoming obsessed with what we would have to do to represent Chinese characters. I got into that and then got into simple programming, which I had done a little bit of already.

Scott Rettberg

Were you using HyperCard then?

John Cayley

No, no. I learned FORTRAN for mainframe programming and then BASIC. I settled on BBC BASIC, and a BBC microcomputer which is the one (a 1981 6502 machine) that they made affordable for people like me and then—I tell this story all the time— since it's true, that a dear friend of mine sent me a letter that was written in acrostics. The idea was that you replaced each of the letters in the text of the letter with a word that began with the letter. It was just a personal letter but then I realized that the process would be really easy to code. This was before I knew about Jackson Mac Low or Cage; before knowing about acrostics or mesostics, but I realized that this was simple to program and yielded very interesting results. Later I also discovered Emmet Williams and Universal Poetry, which was also more or less the same thing.

Scott Rettberg

What would you say were the main concerns of your early work? Because it's quite a bit different from your later work. Early on, you had a real interest in the letter as a unit. You had a real interest, I think, in the sign and the sort of movement between languages, between ideas, sort of representing that in a material way on the screen.

John Cayley

Yeah, I was very much into letters. And at the time, in the literary sphere I was into translation. Translation seems to be— I think I probably instinctively knew that translation is process-based, which is something that I still believe. Translation is a process. It's a linguistic process and yields literary results. And so the idea of using processes on linguistic material to see what happens and to propose that this was poetic seemed obvious to me. And I was much more interested in randomization, supposedly radical experiments with poetic composition that could be as arbitrary as you liked.

Scott Rettberg

Yeah, I suppose aleatory techniques were already out there, but they are still being productively explored quite a bit. I'm wondering about your sort of touchstones, I guess you've mentioned a few authors who you are interested in. John Cage is somebody who you probably think about quite a bit.

John Cayley

Well, now. Yes definitely. At the time like I say I was I was relatively naive about the about the poetic writers who were most obviously doing the type of thing that I was then doing: Emmett Williams, Mac Low, and Cage but—

Scott Rettberg

Had you always considered yourself to be a poet, before this?

John Cayley

I considered myself to be—involved with the innovative poetry scene, and I thought of myself as a poet, but I was pretty much a minimalist. I would go to poetry readings and hang out. But I wasn't very productive. I'm still a bit of a minimalist, but I was definitely into it. And they were welcoming, that community was welcoming to this sort of experimentation.

Scott Rettberg

So, you did you sort of have a scene where there were other people doing this? And this was— you were living in London?

John Cayley

No, I started out in the North of England. In Durham.

But I was in touch. At that time, I was also working on Ezra Pound and I was writing some sort of post-Poundian poetry, and essays about the Chinese in Pound. I got published in a magazine called Agenda which is pretty famous. And so I had some hooks into London, Though Agenda was way more conservative than most of the poetry scenes that I was hanging out in. But nonetheless—

Scott Rettberg

And were there other people, or did you know other people at the time, who were doing digital work?

John Cayley

No, not at the time. Nobody. I mean there were people doing process-based work and there were editors who I was in touch with who were learned about Mac Low. I remember sending off a piece I'd done which was just basically randomizing lines to a guy who is a fairly well-known editor and he wrote a relatively serious note back saying "Yes, very interesting..." But what he was clearly really saying was, "I'm not so sure. Do you really know what you're doing?"

Scott Rettberg

Yeah, yeah, well I still get that.

John Cayley

Yeah. We all still get that.

Scott Rettberg

Just thinking back to some of your I guess earlier works, for example Speaking Clock, though by then you'd already been creating for quite a while—

John Cayley

I think that's right.

Scott Rettberg

But one of the things that's notable in this period of your work— there is an interest in transforming time, or thinking about time-based poetics, and then materializing them as language, in a kind of concentrated minimalist way, but thinking about the dimension of time as being a poetic dimension in addition to being an engine for a literary recombination.

John Cayley

Yes. Well, I mean there are two things. I mean the way you presented it, bringing up Speaking Clock, there are two things there. There is one which is literary or language art performance as time-based performance or artifacts that are time- based. And then there's time as a sort of subject, as a subject of a literary language artifact and Speaking Clock is both. But you can do one without the other.

One of the things that computation made clear is that it's obvious that poetry presented in what I think of now as the typographic realm could be presented in time. On screens it can be done. The idea that the poets wouldn't get on that and start figuring it out... that seemed insane to me and it still seems completely insane to me now—that they haven't solved it, that they're still— you've got the open field, you've got all this crazy punctuation, you've got all of that stuff. But we don't have—in a literary arts department I still can't teach a program (such a program doesn't exist) that many poets might conventionally use in order to make their text dynamic. Why wouldn't they? And this is part of a larger problem of poets not knowing how to read their work or (generally) not thinking that performance is important. We retreated to the page at a certain point, which I think is a perfectly nice space—

Scott Rettberg

Yeah, it's one of the good spaces.

John Cayley

One of the great spaces, a good place to read. But the idea that that space should be in opposition to time-based performance of similar work that also has language as its medium? That's crazy.

Scott Rettberg

And this idea that there is a right way to perform a poem, an almost ritualized style of reading it.

John Cayley

Yeah. So it's ritualized, or just not really a performance at all. It's just a surrogate for what you're expected to do which is to go back and "read," read the poetry "properly."

Scott Rettberg

I suppose one of the elements of kinetic poetry or programmable media in a general sense is that instead of the poem just being an object of contemplation, the poem itself is performing, not just the poet.

John Cayley

Well, I mean these days I'm back to, as you know, I'm back to aurality as being … as being the privileged space where language and linguistic artifacts are, where they dwell, where they can be read. And for me because of recent reading, the literary space is inside aurality. But you know this is not accepted dogma. Literature is supposed to be literature, it's supposed to be the bee's knees. But I think it's a subset of aurality. And that when you read literature, inevitably—and this is not just me but other theorists have said this, —you do this thing, you evocalize. So as you read, even if you're silent reading, you're generating a voice, a time-based voice, in your head. And properly speaking the substantive linguistic material at the moment of reading is being brought into aurality even if there is no actual sound. And I'm pretty serious about this now.

Scott Rettberg

But you're also visualizing in a way, aren't you?

John Cayley

It depends what you mean. Visualization in arrangements of typography? You might be doing that.1Scott asks about visualization here and he probably means the type of visual imagination that we generate when we read. But in my answer I remain focused on the experience of language itself, an experience of language that occurs as we read. What I'm saying is that silent reading in the typographic dimension evokes integrated language in its privileged, substantive realm, which is typically aurality (although for the deaf community this would be an abstracted aurality which may be referred to the phenomenological voice as discussed by Derrida and others in Voice and Phenomon amongst other places). Jacques Derrida, Voice and Phenomenon: Introduction to the Problem of the Sign in Husserl's Phenomenology, trans. Leonard Lawlor, Northwestern University Studies in Phenomenology and Existential Philosophy (Evanston, Ill.: Northwestern University Press, 2011). As this evocalization occurs the reader is still experiencing language, language itself. The language then generates other imaginative experience, that we may think of as visualization although, in fact, this imagination can and does refer to any and all perceptual domains. Reading (to include hearing-understanding) brings out the inherent synaesthesia of linguistic artifacts. [JC] You're reading the typography and you might have sort of peripheral fantasies of how it could have been arranged. But the main the main thing you're doing as you're reading is performing in your language, the language that is normally your first language, and you're performing it inwardly. You get a lot out of doing that: puns, ellipses, ambiguous segmentation, other syntactic ambiguities, all of those things come out as you evocalize. I owe a great debt to a theorist called Garrett Stewart for this.2Garrett Stewart, Reading Voices: Literature and the Phonotext (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1990); The Deed of Reading: Literature • Writing • Language • Philosophy (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2015). He wrote a number of books about reading, you know, reading literary work, and then having the realization that the reason why you get so much out of it is because of this phenomenon—what I'm calling evocalization—that occurs in the process of reading.

So, you know, for the poets, the poets of today, the idea that they're—when they talk about materiality of language and they're talking about the materiality of typographic language in small press publication on fine paper, and they get really worked up about that, rather than getting worked up about the materiality of language as brought to life (and reading) in vocal performance. And I'm not talking about slam poetry. I'm just talking about reading the work like it's heard when it's composed as well as being set on the page. It's another thing that I no longer understand about some avenues of poetic practice.

Scott Rettberg

Let's come back to your journey. One question I have, and this is something that comes up a lot with electronic literature authors, is the question of "Is there a career in this?" I'm thinking back to your years living in England, you were running a bookshop for many years, right, a rare bookshop?

John Cayley

Well yeah, I was a no-hoper grad student in the north of England. And then finally got a job in the British Library in London. And then I left that after a few years to work in a specialist book dealer's. And you know if you're talking about the idea of having a career in poetry, as I would then have thought about it, even if it was an extended version of poetry with different affordances. No, a career in this was not possible. There was nowhere to study it. No money in it. It was just stuff that people like me did.

Scott Rettberg

It was more of a vocation than an employment situation?

John Cayley

I don't know.

Scott Rettberg

And yet you ended up doing it as a job. So there is hope.

John Cayley

Yes, there is hope, there's always hope.

Scott Rettberg

I don't know how theoretical we want to get here, but would you say you have had some interest in deconstructionism in your work?

John Cayley

Absolutely. I mean, I did. I did. I was in— in Chinese studies, my professors were anti-theory. They were actively anti-theory, even though they were linguists, but the question of linguistics is a fraught one, "theoretically," it really is. I've been reading about this recently. You know: Is linguistics a science? Eh, so-so. And then I hung out a little bit with people in the English department because of my work on Ezra Pound's poetics and I became aware of theory at that point. I became aware of theory relatively late for a graduate student.

And then I tried to get into it and tried to understand it and I advertise myself now as a Derridean and I think that now I can plausibly say that this means something, but I wouldn't have said that of myself at the time. I would say that I was interested, and I picked up some of the ideas in a grazing sort of way and I used some of them in some of the work, but I don't think I was a theorist then. I think I was quite good at reading theory and quite good at enjoying it. I'm still pretty good at reading it, pretty good at enjoying it, and now I kind of aspire—

Scott Rettberg

To translate some of the ideas into your creative work?

John Cayley

No, literally, these days I say—when I dare to in front of the front of the pros—I literally say that I want to do philosophy of language.

Scott Rettberg

Do you consider some of your work to be exercises in the philosophy of language?

John Cayley

Yes, I do. Definitely. I mean you know, well in our field, there's the famous proposal, "digitally enabled literature is the realization of certain aspects of postmodern theory." And I guess I was one of the people who was questioning that, and with respect to certain aspects of the way that—

Scott Rettberg

With hypertext—

John Cayley

—with respect to hypertext specifically, yes. Nonetheless I think that even undertaking relatively traditional literary practice using digital affordances does imply no going back. Right? But it doesn't stop literature existing. It doesn't mean that stuff in digital media is inherently "good." It definitely doesn't mean that.

Scott Rettberg

Not inherently.

John Cayley

But it does mean that literary scholars are now obliged to figure out how to encompass a much wider range of potential forms.

Scott Rettberg

Yeah. Which is the exciting part. But it's also the difficult part to translate to traditional literary studies. And even now—probably at Brown it's a bit different—but I think there is still a lot of resistance to digital writing in creative writing programs. The majority of them around the world, you know in fiction writing programs, everyone's still trying to get published in The New Yorker.

John Cayley

Yeah.

Scott Rettberg

And in a way there's more—I think I see more of a conservative bent in writing programs than you do in the literary studies side of it.

John Cayley

More conservative theoretically in Literary Arts. Yes, so there's slightly less willingness to experiment formally in the way that you or I would experiment. But there is an equal conservatism in the Literature departments. And now we've got "surface reading." Have you heard of that?

Scott Rettberg

Surface reading?

John Cayley

Yeah. Because what we all grew up doing was "symptomatic reading." That's when when you're reading but it's not really what it means. It means this other thing. Right? And then there's New Historicism and all that. And now there's "surface reading," which is sort of like, they mean, just reading (again). Let's just read the text. And just talk about it.

Scott Rettberg

OK.

John Cayley

And there's a movement to do that.

Scott Rettberg

Talk about it only at a surface level?

John Cayley

Yeah, let's hope it stays calm, kind of. (Laughter)

Scott Rettberg

Yeah. OK. Surface reading....

John Cayley

I'm pretty sure that's right.

Scott Rettberg

Let's come back to the narrative of your movement. You did eventually find a community of people who were doing digital poetics. You started going to, I guess, the early e-poetry conferences?

John Cayley

The first thing first things I went to were hypertext conferences. Well actually I think the first thing that happened was at the Frankfurt Book Fair where I encountered … which company was it? One of the people who was publishing on floppy disk. Not Voyager? —Was it an American company and or did it have British connections? It's shameful that I can't remember.3This was 1988 or 1989 and the company was a Voyager spin-off, Expanded Books. But anyway, I do remember thinking "Oh my God this is it." The end of the book. That was my "end of the book" moment. Floppy disks! "All academic publishing should migrate to this now," I thought.

Scott Rettberg

It's interesting how in a way electronic literature has come back to books quite a bit, where people are representing the output for example of complex poetry generators by publishing books. And there is this acknowledgement of the ephemerality of the device.

John Cayley

And then for some reason I started to go to conferences—It's very odd, seeing as I was just employed by a specialist bookseller, but the guy who I was working for was an early adopter of computation. He was real gung ho about computerization for mail-order bookselling and he had a very cool early set up in the book store, so he was kind of curious, and he was willing to indulge me even though you know he didn't have a lot of money but he was willing to indulge me to think about these things. So I did, and I started going to conferences basically for my own reasons. I didn't have an academic job. I went to all the conferences, the hypertext conferences and all the early Digital Arts and Culture (DAC) conferences.

Scott Rettberg

I do sort of miss Digital Arts and Culture. Because it seems like a lot of the conferences have gotten narrower, in a way. It was nice to have that environment where it was you know, it was digital culture, and it was performance, and it was digital art, it was computer games, and electronic literature all together in the same soup. I just attended one of your cross-discipline Brown Arts Initiative events yesterday, and it seems to me in a way like you're sort of trying to create that kind of space again, where you have different disciplines speaking to each other.

John Cayley

Well I'm not sure about that. But I do agree that DAC was a bit special. It was very, very odd and you know it should be said that Espen Aarseth— you know he was another reason why I've kept going. And he paid attention to stuff that I made at a very, very, early stage, and he was into it. He came over to London and we met. And then he started DAC. Espen was— retrospectively I thought—well he's a bit academic, isn't he?

And I thought— I was obviously sort of flattered that he was interested, and I was very interested in his book because at that time he was "cybertext" and everybody else was doing hypertext. And he was right. Because cybertext was bigger and more interesting than hypertext. I was totally on board for that and his skepticism was also a great quality. He was you know a proper literary scholar trying to figure this out, someone, you know, who knew his narratology, knew his literary theory, knew his rhetoric and was trying to figure out what the implications for all those things were. And every now and then I go back to the book (Cybertext) and I think this is really good.4Espen Aarseth, Cybertext: Perspectives on Ergodic Literature (Baltimore and London: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1997). There's a lot to it. It really does deserve its reputation. You can hand this to one of the high theorists and you can say, "You can't really ignore this one."

Scott Rettberg

Yeah, I think it had an effect of widening the field of approach

John Cayley

And then he left—

Scott Rettberg

And then he left the field.

John Cayley

And then he left us, and that makes it even better because he's sort of, like, "I've dealt with you. You sort yourselves out, I'll go off and do the same for games."

Scott Rettberg

Yeah, where people really interact.

So, I met you in the late 90s when you won the first ELO Award for Poetry, for Windsound. I remember when I first taught a course in digital literature, we had the video recording of Windsound and I said "All right, class, now we're going to watch a digital poem for the next half hour" or something like that.

John Cayley

I forget how long it runs.

Scott Rettberg

But there were a few different elements at work. There was the textual element on the screen. There was an audio element. There was a time element, but you were very interested at the time in this idea of transliteral morphing. And I thought maybe you could say a bit about that and how it fits conceptually into your project or what you're exploring about the nature of language.

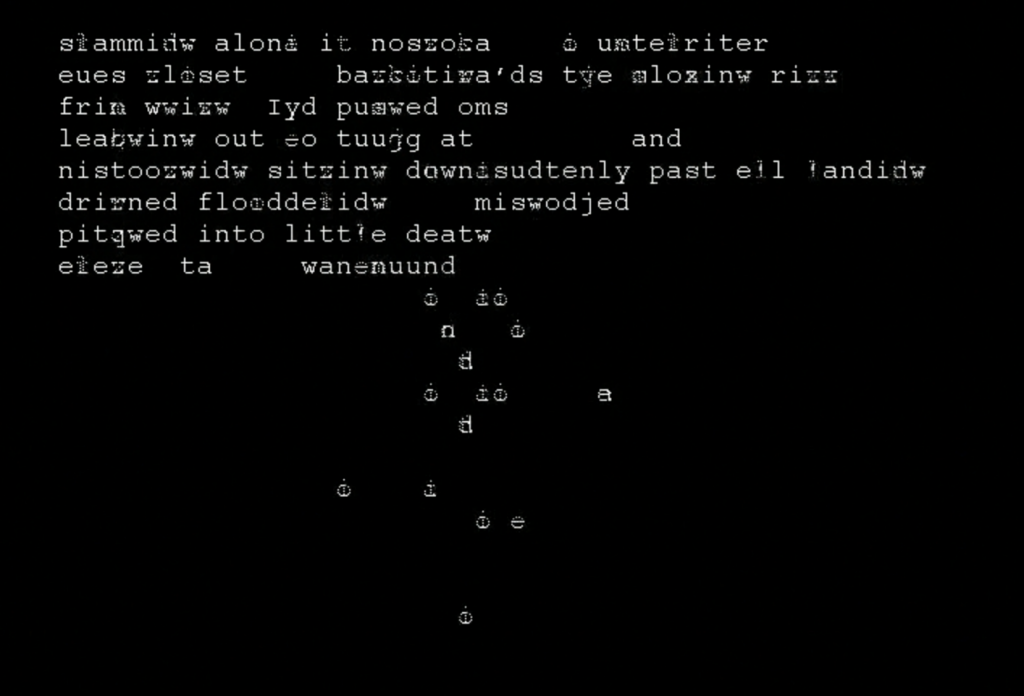

about project | performance transcribed as digital video, 2006

John Cayley

Yeah. That's very interesting. I mean the great thing about Windsound is that it had a proper artistic and aesthetic impetus. Key parts of it came to me as a vision, which doesn't happen to me very often. So it wasn't just a formal exercise. A lot of what I do is formal exercises that I'm trying to turn into something that might deserve attention, but Windsound was a case where the content, I thought, already deserved attention and then the formal shape offered itself, along with a generous narrative.

Scott Rettberg

Yeah, it was a narrative.

John Cayley

It was conceived as a text movie because I had this idea that text movies should exist, and I did imagine cinematic images, but I couldn't use a camera. So, I wanted to try and do that with language and in Windsound the sound was also an important part of it, although it's very simple. I was making a lot of recordings at the time, just pseudo-binaural recordings. I used a recording from when I was in China, just a loop in which there is quite a lot of wind sound but there are also these nice quasi-narrative event sounds within it.

And then as you say, the transliteral morphing. The transliteratal morphing is, you know, you've got one text, how do you get to another text? The analogy, the analogous situation is translation, which is fundamental to my thinking, but then how could you do this, how could you trans— could you get from a text in Chinese or a Romanized text in Chinese to a text in English? How would you do that? How would you plot the— How would you interpolate, as I learned later to call it, between those two states? And so it was a question of just thinking that through. And in this case wanting to go from one text to another text and also to do some replacements of proper names shared by the texts.

What's going on in Windsound is that there are two parallel narratives. There's a narrative in the past that's happening in early Republic of China during one of the Japanese occupations and then there's a contemporary narrative involving myself and a late friend. So occasionally the characters get replaced. The names get replaced, the proper elements get replaced. Most of the text stays the same and these "slots" get changed. And then you go from one distinct text to another distinct text (the next passage in the stories) and you've got the interpolation problem. So, I just thought it through and I figured out a way to do it which was based on letters which are problematically related to language as such. We know that letters don't actually represent anything reliably other than letters. They don't. They don't map onto phonemes. They don't give a particularly good indication of anything. They're just what they are. Right? But they have associations which are linguistic in a post-Derridean linguistics and philosophy of language, and you can work with this sort of thing. You treat all linguistic performance as synesthetic and having associations even though the significations of the forms are arbitrary in strict Saussurean terms.

So you can make a loop of letters of the alphabet and you can arrange it by letteral similarity. Letters are clustered together if they indicate similar sounds or sort of look alike. I just made compromises about all this and then used that sequence once it was established. From any letter-point in the loop to get to any other letter the maximum number of steps was 14. It's very straightforward and wouldn't take a professional computer programmer long to figure out.

Scott Rettberg

It also seems to represent an effect that I perceive as a visual material representation of translation, but there's also this sense that it's showing an idea in the process of becoming. There's this in-between state between idea and vocalization that you sort of see there.

John Cayley

Yeah, it suggests that, and I like that. I mean— These days if you're doing what I tend to do, theoretically underpinned language practice of some sort, it's a bonus when you get something suggestive. You can always be hardcore about it and say no. That's just random, that's just chaos. Forget it, just let it happen. But if it's suggestive of something that makes people think "Oh it looks like it's trying to say something. We're in the middle of meaning: somewhere in between German and English." Then, why not?

Scott Rettberg

And it's interesting that your poetics— I guess that some of your work, I would say, is much more conceptual, poetry at the level of language poetry, you know the sort of work where you're working through concerns purely at the level of concepts and ideas, whereas some of the rest of your work differs. Windsound was narrative but also for example riverIsland I think was in some senses about your father, if I'm recalling correctly. So there's a personal element.

John Cayley

In part. Yeah.

Scott Rettberg

So how do you balance those two? And then, to add another layer: I think that we'll get to talking about an engagement with the conditions of present political reality. So those are three different layers. But how do you balance those? Do you see yourself pulled towards those things in different ways or are they all of a piece?

John Cayley

No, they're not all of a piece, and I don't have that worked out.

And I think that a particular type of practitioner like me spends quite a lot of the time wanting to— Growing up there was quite a lot of emphasis on depersonalization, anti-anything-personal for almost pseudo-religious reasons. East Asian philosophy, and Cagean pseudo-egolessness and all that sort of stuff. So, it's not about me, it's not made by me. Nothing to do with me. It's just pure. It's like a pure artifact. So, if you grow up with that or you form yourself in that context then you give up, you risk giving up, saying what you actually want to say about stuff.

So you know like I just said Windsound for me was a break. You know, the most personal I got before that was translating Classical Chinese poetry. I liked it. But seeing as it's fairly egoless, abstract, that was fine.

And now I think that it's kind of incumbent upon you, if you have a chance to produce aesthetic artifacts to— if you don't have anything to say then don't say anything at all.

Scott Rettberg

I certainly agree with you. And I think there is this pull— you know I talked about this a little bit in my book [Electronic Literature]5Scott Rettberg, Electronic Literature (Cambridge and Medford: Polity Press, 2019). but in our field there is this pull towards innovation and a technological idea of innovation where it's like: Here's this new technology. We've developed these new techniques and here are these new ideas and you can work them through, and that's exciting in and of itself, but at a certain point it becomes a kind of empty exercise, if that's all there is to it.

John Cayley

Well it's an empty exercise that also risks being in alliance with the not-so-empty exercise of the innovation that is constantly discussed in terms of digital progress.

Scott Rettberg

Let's talk a bit about your recent work. By that I mean maybe the past 10, 15 years or so. You've been engaging significantly with the corporate apparatus of the network. You know, if we think about the Web and where it was at the beginning, that was a really exciting moment for electronic literature. Because it was this time of great connections and also this moment of this possibility of people actually reading the work [Laughter] elsewhere and then suddenly you are connecting to other people. And then we had, you know, I guess they called it Web 2.0, the growth of social networks, and the growth of the mega-corporations and the sort of closing of the commons of language, as I think you've described it. Your work took a turn then. Can you maybe say something about that turn and how those concerns became part of the point of your work?

John Cayley

Well you know I'm thinking now that saying "If you don't have anything to say, then don't say it," is not quite right, because there are moments where you notice new things happening that you suspect are going to be culturally interesting. And if you're ahead of the curve on them— I still get a kick out of believing that I'm ahead of the curve on certain sorts of technical, technologically-implicated cultural advances. Let's put it that way. So I'm still into that, but I am as you suggested, primarily now interested in this in terms of what I see as the underlying politics of what I call the regime of computation, the big software architecture or however we want to put it. And yes, I don't think that— it's not like I have aspirations to be an activist but I do have, I feel I have a duty and I get pleasure out of indulging in a rant whenever I'm given a chance to do so because I see many serious problems unaddressed by any of us. For culture in particular, in the current situation. And yes it's true that I started to figure this out when it was clear that Google was enclosing the digital commons and also when Google was beginning to seriously to look at the Natural Language Processing implications of their search algorithm. And then it's impossible to exaggerate the incredible things that have happened since. I date it from 2004, when Google launched Gmail.

Scott Rettberg

Once they started reading our mail.

John Cayley

Well yeah, that was another thing. I remember noticing while teaching at Brown and saying, "Hey students, did you notice that we're doing all this fancy stuff, but they're doing way more interesting stuff?" But it was the moment when Google figured out that they had to have a way of having people's accounts and that they had to have accounts of actual humans: enough of them to be able to figure out what humans did. And the way to do that was to give them free e-mail, and to try and get them to register properly, with their real names. Facebook, obviously, was doing the same thing. You had to look like a real person before they would accept you. And so they'd figured out that everybody needed an account. When they figured that out, the game was up.

Scott Rettberg

And the Internet was no more.

John Cayley

Yeah, the Internet, well, the Internet as some of us knew it for a very brief moment.

Scott Rettberg

Yeah.

John Cayley

Always already gone.

Scott Rettberg

We kind of went from this time, you know we all had our home pages, we had little outposts, and these metaphors of freedom to— to something else.

John Cayley

And since then, for me, it's been a steady progression from that moment. If you remain— if you remain focused on language and the role that language and linguistic practice plays in these developments that are going on, right across culture, then there are a number of things that I believe people like me and language artists can contribute in order to show, just to simplify, to show inadequacies of the proposed infrastructure.

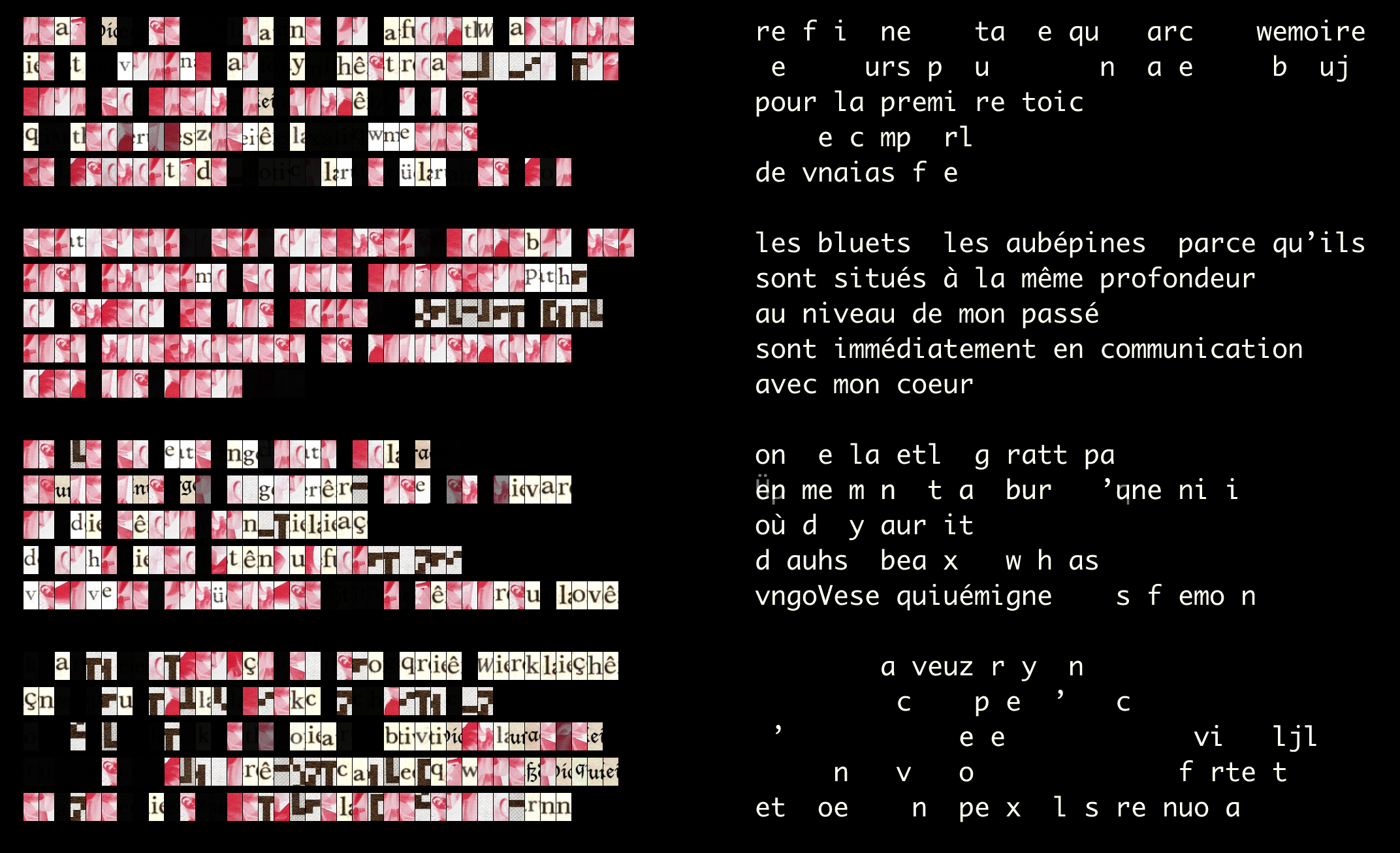

about | refactured for the web, 2019

Scott Rettberg

People often ask me, or I often think about, this question: "What are the uses of electronic literature?" And of course, that's a sort of, you know, a kind question that's always asked of any kind of humanist or creative artist. But increasingly I'm saying well here is a very clear example of one of the things that electronic literature can do, to make visible that which is occurring that we are ignoring or that's happening too quickly for us to even process: how we're being changed as a result of our interactions with the digital.

I mean you can go fairly far with this, right? We certainly can look at what happened with the 2016 Trump election and the interactions that occurred on social media and their effects on our polity. But I think there's also something to Hayles's, and other people's, ideas that our thinking process is also being fundamentally altered as a result of our engagement with the digital. Certainly, the way that we write has changed. But maybe also the way that our brains work.

John Cayley

Yeah. I— because I spend most of my day thinking about these things— I don't quite buy that. My current position is sort of radical humanist, one that accepts the scientific validity of evolution. Thus the implication that anything that we might do culturally will have an effect on what we are fundamentally — since, you know, we've evolved to be a particular type of entity— is obvious bullshit. But, that doesn't mean that you just become a fatalist and say well anything goes, we can and should do anything. Because you know, how you organize your culture: that's up to you. As animals that have culture, we should have the culture that is appropriate to our human animal nature. And that means that we shouldn't necessarily have to have a handy, fast food, digitally monitored, you know, quantified culture. We don't have to do that. There's no need. And we would be impoverished by it. Instead of having many bookstores or many types of reading experience, for example, we become inclined to choose impoverished versions. For no good reason, just because it's cheaper, because everybody does it that way. That's the source of the oppositional agonism for me.

But when it comes to language you can show how something like this could plausibly happen, or I think you can. It's obvious that currently computation uses text, and text is simply a sort of transcription, in the current state of the game. It's a transcription system. It isn't a very good one. So you know, for example, if you're doing word embedding with a corpus, that is doing "word" embedding with a corpus of text. You get text back. You don't get language back because you don't have the data for that yet. And you may never get it if you're not careful.

Scott Rettberg

But maybe Google does?

John Cayley

No, it's not that Google gets more. Google is also living in the delusion of— the whole of big software infrastructure is living inside of the post-Second World War model that presupposes that language is computable, that the mind is computable. You know, in a very straightforward way. Like it can be represented in ones and zeros. Eventually you'll get there. Eventually you'll have a model. And I think that's just silly. And it's not just me that thinks it's silly, humanists all know it's silly, but they don't have very good tools for dealing with it.

Many of the scientists have— my other famous rant is Gallistel's problem. Have you heard me talking about this? No? So C. R. Gallistel is a sometime associate of Noam Chomsky at M.I.T., still around, still doing neuroscience and investigating how animals learn, rats and bees and stuff. And he hates machine learning, because he doesn't think it's learning.

He thinks that learning is what is done by people and other living things who already know a lot about the world and then can add to that in interesting ways. Whereas machine learning for him is just abstract pattern recognition that can be enabled to model what already exists and then maybe learn a bit more after that. But you've wasted all that time, emulating stuff that already exists. Then he points out, because he works with Chomsky, and Chomsky accepts this in one of his books,6Robert C. Berwick and Noam Chomsky, Why Only Us: Language and Evolution (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2016), 50-51. that if you can make a rough calculation of the number of operations you would need to have a reasonably good, working Chomskian grammar of a natural language, so you can make an estimate of how many operations you'd need, then you can look at the current understanding of neurochemistry and electrical behavior in the brain and you can calculate how much energy you'd have to use if you made that many operations and you come up with the result that if you did that— with what they currently know about the brain, your brain would boil, it would heat up much too much. In other words, the amount of computation that is required even for a Chomskian grammar which is nowhere near what the brain can safely do.

So, something's not right. There's something not right about computational models and there's something not right about using them as having any purchase on linguistic practice.

Scott Rettberg

At the same time though, we're increasingly— you know, we can argue about thinking machines or whatever or whether that's sort of a silly concept. But at the same time, algorithmic processes are interacting with us in ways that now shape our behavior. This is in line with Søren Pold and Christian Ulrik Andersen's idea of the Metainterface as kind of flipping the relationship, from us using computers through the interface to computation using us to particular ends.7Christian Ulrik Andersen and Søren Bro Pold, The Metainterface: The Art of Platforms, Cities, and Clouds (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2018).

I wanted to get to one of the ideas that your work explores: reading, machine reading. Whether we think of them as thinking machines or not but certainly the machines are reading our behaviors and they're reading our texts as well. And maybe you could say just a little bit about how you represent some of that.

John Cayley

This is part of the same argument. Or it relates, in that the whole notion of thinking or intelligent machines is entirely over-determined by post-Second World War computational models of language, which I'm sort of saying were never right in the first place.

I accept that we are constantly interacting, or transacting more accurately, with algorithms. Insofar as they are "intelligent," they are intelligent as a whole, so as to include all of their system apparatus and their interfaces. So whereas the post-war regime of computation still has the mind/body split and still locates any "intelligence" in the computational operations, the abstracted operations, it's always misdirected. So we have to have humanists like Søren and Christian saying "No, no, it's the interface dummy, that's the smart part." That obviously is the smart part. It's not it's not just that Google has got the algorithms. Google's also got the web design, the devices, the interfaces. They're designing that for us. So there's that. And then there is the inadequacy of the algorithms themselves, and what "data" they're actually using. If they're purporting to use language, purported to be "thinking" using language— as if that was possible without a body—then you can show that they're not even using language, they're just using text at the moment and for the time being. So they may be very, very, very good at manipulating texts combinatorially and making the text fit into certain interfaces that we find attractive enough to buy stuff with, things that we think we need. Yes. They're manipulating our behavior because they're making us buy more things than we need. Yes. But they're not they're not reading and they're not actually generating language. Not generating real language. Not yet.

Scott Rettberg

They're not reading in the way that we read, anyway

John Cayley

They're definitely not reading. Machines do not read, in my world.

Scott Rettberg

Some people would disagree.

John Cayley

I know, but they're wrong.

Scott Rettberg

So maybe one last question before we go. I just wanted to ask you—you've been teaching digital writing or digital literary arts for a decade or so—

John Cayley

It's over a decade now.

Scott Rettberg

And I was just wondering what you hope to transmit to your students or what you hope your students will get out of the experience of creating in digital media. What's their role? What's the legacy?

John Cayley

That's a good one. Well I mean I still— I would say that the most fun that I've had with all this stuff is very, very, occasionally thinking that I've either made or been part of making something that really was kind of for want of a better word: beautiful.

I'm a little bit— you know, I know that that's a problematic term and I don't mean literally beautiful but still…. I think that I like students to go away thinking they can be artists in that sense, that they might actually produce some beautiful stuff before they go. The critical art practice which I read as underlying your question? I think that's really important. But I don't think it's up to me to say. You know they don't, they shouldn't accept my critique. If an idea within or an aspect of my work is critical or critical art practice, like I'm trying to get at something, then it seems unlikely that I actually know what it's really important to get at. But I hope that my students will continue to look for the art or critical art practice that is most important to them.

Scott Rettberg

And maybe do both at the same time.

John Cayley

And maybe do both at the same time. They should. And I hope that some of them will actually figure out ways of having careers, and we've talked about this earlier, but I don't see that as my job.

Scott Rettberg

Yeah. Well you've had good luck with that. Actually, a lot of your students have come up with careers in the field. But thanks a lot. This was a good conversation.

John Cayley Well, thank you, Scott. I think that it's always fun to have a conversation at a heightened level of intensity.

Bibliography

Aarseth, Espen. Cybertext: Perspectives on Ergodic Literature. Baltimore and London: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1997.

Andersen, Christian Ulrik, and Søren Bro Pold. The Metainterface: The Art of Platforms, Cities, and Clouds. Cambridge: MIT Press, 2018.

Berwick, Robert C., and Noam Chomsky. Why Only Us: Language and Evolution. Cambridge: MIT Press, 2016.

Derrida, Jacques. Voice and Phenomenon: Introduction to the Problem of the Sign in Husserl's Phenomenology. Translated by Leonard Lawlor. Northwestern University Studies in Phenomenology and Existential Philosophy. Evanston, Ill.: Northwestern University Press, 2011.

Rettberg, Scott. Electronic Literature. Cambridge and Medford: Polity Press, 2019.

Stewart, Garrett. The Deed of Reading: Literature • Writing • Language • Philosophy. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2015.

Stewart, Garrett. Reading Voices: Literature and the Phonotext. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1990.