Between Plants and Polygons: SpeedTrees and an Even Speedier History of Digital Morphogenesis

Toward a more expansive standard of botanical, graphical, ecosystemic and (not least) digital realism.

Function and flow stand in for matter—qualities that are ultimately symptomatic of the electric and the electronic.1

The following essay sets out partial and preliminary thoughts on the burgeoning world of digital plant design, both as a nascent media industry and in more philosophical terms as a way of rethinking computational mediation of natural entities and processes. Although in some respects a critique of computer-generated plants as invasive simulacra proves valid, I also attempt to demonstrate their value as emblems of conflicting approaches to vital simulation—in most cases, digital plants remain largely static representational objects produced as if ex nihilo by design software, but in others, they are formulated from the start as changeable, process-driven, and susceptible to outside conditions. Increasingly ubiquitous, digital plants pose unique and edifying challenges to scholars of environmental media, artists, scientists, and general audiences, as well as the reigning narrow standard of graphical realism in computer simulation.

Botany as Algorithm

In the opening shot of the 2009 film Avatar, the voice of paraplegic ex-Marine Jake Sully (played by Sam Worthington) recalls dreams of flying while lying wounded in a veteran’s hospital, as the “camera” soars over and then into the canopy of a fog-shrouded rainforest. Of course, the world we see is not just the stuff of a disabled soldier’s fantasies, but the heavily wooded surface of the moon Pandora and the massive “Hometrees” of the native Na’vi people, which Sully has just approached after years of cryogenic sleep on an interstellar spacecraft. Such footage easily would have served in a British Broadcasting Corporation natural history film, yet clearly, given the cinematic fiction, what we see is not the Amazon or a Mexican or Ecuadorian cloud forest but digitally generated trees sold by a company few outside industry have even heard of, despite its now dominant status. This seems an odd omission, given that Avatar was until recently the highest-grossing movie on record (now surpassed by Avengers: Endgame but followed by that other James Cameron blockbuster, Titanic),2 and that the film’s forest ecosystems, rather than its timeworn storyline, were for many its primary draw. Credit for most of Avatar’s computer-generated imagery has gone to visual effects (VFX) companies Weta Digital and Industrial Light & Magic (ILM), the latter called in six months before the film’s completion to assist with vehicle modeling, battle sequences, and, unbelievably, all of the vegetation on Pandora.3

Unable to craft VFX plants to Cameron’s exacting specifications, ILM turned to a small South Carolina-based company called Interactive Data Visualization (IDV), whose proprietary SpeedTree software, as the name suggests, enabled quick yet customizable digital vegetation development. For its first seven years in business, IDV had been working almost exclusively with clients in the game industry—being chosen for Avatar was quite a coup for a company that had only recently decided to offer SpeedTree for Cinema, as well as Games. Years on, what was once a scrappy operation filling an underserved niche has become a genuine behind-the-scenes juggernaut, which can now unequivocally advertise itself as “the standard for vegetation modeling and middleware.”4 In 2015, IDV co-founders Michael Sechrest and Chris King and Senior Software Architect Greg Croft even received a Scientific and Technical Academy Award from the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. In support of their award, the Academy noted, “This software substantially improves an artist’s ability to create specifically designed trees and vegetation by combining a procedural building process with the flexibility of intuitive, direct manipulation of every detail.”5 Not surprisingly, SpeedTree has also garnered recognition from the game industry, having appeared in numerous high-budget games like Assassin’s Creed Unity, Far Cry 4, Dragon Age: Inquisition, and Destiny, from major developers and publishers like Ubisoft, Bioware, Bungie, Activision, Epic Games, and Electronic Arts. For prospective game developers, SpeedTree is billed as “the vegetation software making AAA games great since 2003”!6 Permutations of the SpeedTree software now cater to customers in games, cinema, and architecture, and have even moved to colonize television, beginning in 2011 with Sesame Street. SpeedTrees have now appeared in over 30 television programs, including critical darlings like Game of Thrones, earning IDV a 2015 Primetime Engineering Emmy to complement its Academy Award. Whether this all amounts to the pernicious infiltration of reality by bogus plants—a kind of Macbethian forest on the move—or an admirable advance in the science and art of motion pictures and virtual world design, remains open for debate. Without question, however, SpeedTrees increasingly surround us. As one reviewer put it, “If you’ve seen a tree in a video game, there’s a good chance it was created with SpeedTree.”7 Or as IDV itself boasts on its online store, “9 of the 10 Opening Weekend Blockbusters use SpeedTree!”

Media scholars may be inclined to approach digital plants as a subset of the larger question of computer-generated imagery (CGI), or visual special effects. Kristen Whissel has already, for instance, assessed the impact of contemporary forms of digital morphing, crowd generation, and compositing as producing new modes of cinematic expressivity.8 Others might be tempted to read the linguistic traces evident in SpeedTree’s very name, which promises efficiency even as trees stand in metonymically for plants of diverse kinds, or the metaphorical excesses of SpeedTree’s recent partnership with Amazon Lumberyard, the e-commerce giant’s free but branded game engine for aspiring developers. Yet while there is obvious value in these approaches, in what follows I want to resist two common, but opposing tendencies in scholarship on digital representation—first, the reduction of digital artifacts to a symbolic order, as when Whissel reads the massive CGI armies of The Lord of the Rings film trilogy as figuring historical thresholds, and second, a distinctly Baudrillardian suspicion of digital simulation that takes to an extreme Walter Benjamin’s reflections on mechanical reproducibility and the aura of the artwork. In the case of SpeedTree and its competitors, the question of the digital object’s faithfulness to reality turns out to be much more complicated than the mere presence or lack of an objective referent. Some SpeedTrees are sold as is (for example, the catalog offers one model of a Sierra Redwood for fifteen dollars), but SpeedTree software may also be used to customize existing vegetal templates and generate new ones. It therefore behooves us to investigate digital plants not just as finished products, but also in terms of the social and technical processes that give rise to them and carry them into circulation as commodities. As I will discuss momentarily, the exuberant growth of virtual vegetation is in fact indebted to basic and applied research in many fields, from computer graphics and processor design to morphogenetic study in mathematical and developmental biology. When we attend to the logic of growth and patterning in computer-generated plants (and animals), we thus find ourselves in the realm of digital morphogenesis, or studying how digital organisms achieve their physical form and structure.9 That this occurs through some combination of automated software procedures, artists’ modeling, and user or player interaction quickly destabilizes any easy notion of the CGI plant’s authorship.

Granted, long before SpeedTrees and the harnessing of modern computer power to the problems of plant modeling, many a thinker had observed and attempted to divine the laws of self-similarity in nature. The Scottish scientist D’Arcy Wentworth Thompson ushered in mathematical biology with his 1917 book On Growth and Form, which famously includes his geometric analysis of spiral shells and phyllotaxis (the regular arrangement of plant leaves, seeds, or blossoms along a stem or bud), and mathematician Benoit Mandelbrot managed to introduce fractals into popular parlance withThe Fractal Geometry of Nature in 1982. Today both life scientists and computer scientists continue to describe and model organismal development as the outcome of logical or mathematical processes, among them Dr. Przemyslaw Prusinkiewicz and his Biological Modeling and Visualization (BMV) research group in the Department of Computer Science at the University of Calgary. The BMV lab carries on seminal work done by Prusinkiewicz with Aristid Lindenmeyer before the latter’s passing, best captured in their 1990 textbook The Algorithmic Beauty of Plants.10 Lindenmeyer is remembered for proposing Lindenmeyer-systems, or L-systems, in the late 1960s as a theoretical method to study the development of simple, multicellular organisms. Notably, these recursive, string-based systems were later applied to plants and undergird the science of yet another company in the business of selling digital vegetation and the tools to create it—Xfrog. Xfrog’s co-founders, Oliver Deussen and Bernd Lintermann, have authored their own textbook on digital morphogenesis in the Digital Design of Nature, exhaustively describing both procedural and rule-based “computer-assisted methods for the production of plants.”11 Remarking in their brief introduction that it is increasingly difficult to tell the difference between synthetic computer images and actual photographs, Deussen and Lintermann also acknowledge that botanists and computer scientists are likely to find themselves at odds over the value of the digitally created plant:

For example, for a botanist a geometrical plant model is interesting in two ways: it permits the visual validation of the underlying production process, and it is used to calculate mathematical characteristics, such as the interaction of light with the plant and the environment. The visual model as such is not of much concern here. This is completely different in computer graphics: here the geometrical model is used because of its visual effect. The underlying processes are only important in as much as they must permit us to efficiently produce a complex geometry. The exclusive visual evaluation often leads to the production of botanically incorrect models so that in a certain situation a desired result can be achieved.12

In other words, the digital plant model is very much a boundary object whose purpose and effects vary dramatically as it passes from scientific to aesthetic contexts. For designers, anatomical accuracy may matter less than overall impression or polygon count, as highly detailed models with thousands or millions of “tris” (triangles) are often deemed too costly in terms of computer rendering power. For scientists, the model is less end than means, a way of testing hypotheses and generating more precise mathematical descriptions. Yet pace Mandelbrot, it is important to note that plants are not actually fractals, even if fractals turn out to be one convenient way to simulate nature’s self-similarity.

This is not at all to say that it does not matter whether digital plant generation methods do their best to capture the less tidy and still mysteriously complex world of living plants. As game designers, cinematic visual effects artists, architects, and kindred virtual worldbuilders comb through growing “asset” libraries populated by all manner of digitally created objects, or choose to make their own, it certainly signifies whether plants are treated as readymades or as forms that can grow, undergo seasonal change, wither, and even die, whether they are treated in the precise terms of graph theory or network topology, as branching structures with trunks, limbs, and so on, or as the product of a number of probabilistic or parameterized fields influenced by attractors and inhibitors, or as volumes with internal process (Deussen and Lintermann note, for instance, that simple recursive methods that apply the same rule at each branching work for most North American trees, but fail abjectly in describing tropical trees).13 It also matters whether plants are treated as individuals, or members of communities, and whether they are subject to external influences like light, wind, and soil. While I want to be careful not to subject SpeedTrees and XfrogPlants to the impossible test of digital fidelity to ecological reality, in the next section I take seriously the impact of being surrounded by digital vegetation, aided by new offshoots in plant philosophy.

Taking Stock of the Digital Vegetal Soul

Vegetal torpor is the aftermath of civilization; it is what remains of plant life after its thorough cultivation and biotechnological transformation into a field of ruins.14

Ecologists worry about the slippery slope of biodiversity loss, where accelerations in the rate of species extinction and related reductions in genetic and community diversity lead to a weakened ability to adapt to changing conditions, not to mention an impoverishment of everyday experience. Something similar is arguably afoot in the world of digital vegetation, where a few players like SpeedTree, Xfrog, or the German Laubwerk set the standard for computer-generated architectural, cinematic, and ludic natural landscapes even as their catalogs of readymades and tools for customization expand. Discussing stock photography near the turn of the millennium, Paul Frosh then noted that “super-agencies” like Getty or Corbis had essentially created the “visual content industry” by buying up vast libraries of stock and archival images and hawking digitally decontextualized images to almost any type of client.15 Getty is now the largest stock photo agency in the world, with a library of over 200 million images as well as thousands of hours of footage, while its former rival, Bill Gates’s Corbis, recently sold its images division to the Chinese company, Visual China Group (VCG), allowing Getty to finally acquire distribution rights for Corbis images outside of China. Mulling over Getty’s artfully invented marketing categories circa 2002, Frosh helpfully opined “however abstract and autonomous it appears, content is never just content; it possesses intentionality and directionality: it is always ‘content for’. This means that at a fundamental level ‘content’, to be recognizable and conceivable as such within the digitized visual content industry, must be distinguishable from ‘non-content’, and it is precisely the absence or non-validity of a potential client which designates the latter category.”16 Whatever it contains, the order catalog always raises the questions of who is buying and what has been omitted, or what has been deemed uninteresting, or worse, unsaleable. Returning to SpeedTree, we might ask why, for instance, apple trees are available as seedlings, saplings, and species packs (Figure 1), but guava trees, in any form, are not; why there are 438 temperate deciduous forest products and only 78 subtropical broadleaf forest products; why North American plant models far outnumber Asian ones (as of this time, at 765 to 411); or why Cannabis sativa, ingeniously dubbed SpeedWeed, is made available for the droll price of $4.20. Chances are these products and ratios are less a product of conscious intent than a difficult-to-pinpoint amalgam of customer demand, available expertise, and geographically defined market share, yet they still serve as fodder for rumination.

In part, we ought to wonder if these existing tools and models lead to a narrowing of our vegetal prospects, making our collective digital imaginary into a whimsically curated greenhouse rather than a post-wild, rambunctious garden.17 Like the botanical ideals enshrined in early scientific image-making, when artists for plant atlases or compendia depicted less actual specimens than exemplars distilled from observation and expectation,18 SpeedTrees and their ilk present visual archetypes that may preclude meaningful variation. While studios with robust budgets may be able to afford more dynamic models with support for changing seasons, wind effects, light scattering, and so on, or may have dedicated artists who are able to leverage vegetation software to create bespoke plants with idiosyncratic characteristics (a broken branch, a bent stem), many are content to purchase one-off models and liberally copy and paste them across their virtual landscape. These digital plants, then, are not only of a stock character, but are also essentially frozen at one moment in developmental time. Even when changes do occur—the apple tree blossoms in spring, or sheds its leaves in the fall—they are rarely tied to the underlying artificial intelligence of the system. The CGI tree that drops its foliage from one scene to the next is not reacting to a sustained spell of colder temperatures or diminished sunlight, but undergoing a scripted swap, analogous to the lowering of a new theater backdrop to indicate a change in setting. Eventually, perhaps, virtual worlds will deliver a fuller sense of plants in all their life stages, and in their interactions with terrain, atmospheric conditions, and other organisms.

If all this seems rather alarmist for what are basically artificial plants designed for digital entertainment and visualization, recall the epigraph to this section, drawn from Michael Marder’s radical plant philosophy, which suggests that plants have already been subjected to centuries of domestication, cultivation, and manipulation through agriculture, genetic engineering, and floristry. For Marder, what he calls “the capitalist agro-scientific complex” has turned plants into soulless commodities—growing, flowering, fruiting, and even dying at will.19 In contrast to the vigorous and multifarious growth of unregulated planthood, commodified planthood occurs via monocropping, fertilizing, pesticide application, genetic modification, and even gassing when used to delay or trigger ripening during transport to supermarket shelves and consumer tables. By meticulously tracing the long Western metaphysical tradition of sidelining plants in relation to humans, and even animals, he hopes to reclaim vegetal life through an appreciation of its borderline status between living and nonliving (not quite animal, while drawing from minerals and its milieu), its nonconscious intentionality, quasi-infinite heterotemporality (a plant grows throughout its life and undergoes seasonal and other cyclical variations), non-referential exuberance, and utter vulnerability to its environment.

At the same time, we might return to Frosh and his worry that “the emphasis on ‘content’, abstracted, flattened and universalized” conveniently forgets the materiality of that content and “the networks of cultural, technical and institutional power which make materialization possible.”20 After all, as author Cory Doctorow explains in ©ontent, digital assets inevitably raise questions of digital rights management,21 while the flourishing scholarship on media infrastructures—which includes anything from submarine cables and internet data centers to cell phone antenna “trees”—reminds us to fasten our attention on heretofore ignored aspects of our media environments. Just as Lisa Parks has argued that the camouflaging of cell phone towers and related schemes “keep citizens naive and uninformed about the network technologies they subsidize and use each day,”22 does not the relative invisibility of digitally modeled plants and the processes and institutions that brought them into being indicate a troubling disregard for the ubiquity of computer-generated nature? To circle back again to SpeedTree, few proponents of the product have bothered to note that IDV’s co-founders all got started on 3D graphics programming with the help of Navy funding, or that one of IDV’s first clients was the Department of Defense, for whom they contracted “on everything from electric ship power systems visualization to Eye-Sys, a system that visualized global supply chains, dependencies, and how to disrupt them for the Joint Warfare Analysis Center.”23 SpeedTree, then, much like the internet, self-driving cars, headphones, robotic vacuum cleaners, and other mainstays of contemporary civilian technology, originated at least in part with military expertise.

Of course, unlike cellphone towers awkwardly disguised to look like pine or palm trees, which occupy space that real trees might otherwise have inhabited, a SpeedTree seems unlikely to usurp precious habitat. But all digitally produced nature partakes in electronics economies based on planned obsolescence and disposability, once more a largely concealed culture of resource extraction and toxic dumping historically unparalleled in the enduring character of its contaminants and its energy-intensive, globe-spanning supply chain. As Jennifer Gabrys writes in Digital Rubbish,

From thin screens to tiny chips and from dispersed networks to rapid rates of exchange, many of the qualities of electronics convince us that they are relatively free from material requirements. Yet the term dematerialized does not necessarily mean ‘without material’ but may, instead, refer to modes of materialization that render infrastructures imperceptible or ephemeral. This is electronic technology’s sleight of hand, its magic.24

Those of us accustomed to reading or writing about digital technologies and the worlds they enable without reference to platform, network, electricity, metals mining, or waste, might fruitfully stumble over this and Gabrys’s later declaration that “plastic partly enabled the sense of virtuality.”25 Although Gabrys has materials science in mind here, her statements echo the language typically used to describe digital assets and their demands on computer processing power. “With the rise of automation and electronicization, materials become increasingly indistinguishable from their performance,” she writes. “Materials are assessed for their performativity; they are engineered for efficiency, functionality, and, on a certain level, elimination.”26

What’s more, digital plants and the artists who craft them clearly rely on what is known about living plants—what happens, then, when the latter disappear? In a piercing indictment of Husserlian phenomenology as encapsulated by Husserl’s argument that the destruction of a tree matters little to the reality of one’s perception of a tree, Marder wonders:

But the question—and this is no idle speculation—is what will happen to the noema “tree,” after the last tree simpliciter is destroyed? To what extent can the signified tree persist in the absence of an actual tree growing in my backyard, in the unique Costa Rican cloud forest, or anywhere else in the world? […]. The virtualization and idealization of vegetal meaning goes hand-in-hand with the actual destruction of plant life; something of meaning always burns up along with the plant itself, even one as meaningless as the Husserlian tree simpliciter.27

While Marder’s issue lies with philosophy’s penchant for treating plants as convenient thought experiments, a similar “virtualization and idealization” occurs with digital vegetation, with a similar tendency towards overlooking material realities. Remember that Sierra Redwood on sale for fifteen dollars in the SpeedTree library? Also known as Giant Sequoia (Sequoiadendron giganteum), in its native habitats it is considered an endangered species.28If, indeed, both philosophers and 3D graphics artists require “at least the possibility of a perceptual approach to the plant,” it turns out (as it usually does) that virtual reality is not so distant from reality, in the end.

Natura ludens

On the one hand, then, SpeedTrees and XfrogPlants and their close cousins represent precisely what Marder finds reprehensible about, say, the produce industry’s efforts to control the temporality of plant lives. Plants are not necessarily fulfilled in the process of producing fruit for human consumption, so Marder does his utmost to decouple plant life cycles from capitalist timelines and what amounts to a kind of botanical reproductive futurism. In fact, Marder equates vegetal being with play, something we ought to keep in mind given SpeedTree’s prevalence in digital games and what will be my concluding case study: the environmental art asset design for the indie game Firewatch. For Marder, the freedom of plants may be partly attributed to”the play built into vegetal life, strangely indifferent to its own preservation.”29 Looping back through Derrida to Kant, Marder winds up celebrating at least one aspect of Kant’s recurring interest in the tulip, namely the idea that “Only in becoming superfluous, unproductive, and un-reproductive, is the tulip beautiful.”30 This emphasis on excess or refusal to produce in an aesthetic context, perhaps best embodied by the cut flower, is notably reminiscent of keystone texts in game studies, which commonly define games and/or play acts as being foreclosed from matters pertaining to the “real world”—thus betting or gambling that aims at winnings, for instance, does not qualify as genuine play. While Marder, with help from Schiller, rephrases the antique notion of natura naturans (Latin for “nature nurturing”) as natura ludens (“nature playing”), the Dutch historian Johan Huizinga long ago penned Homo ludens, most often translated as “man, the player.”31 Marder’s natura ludens speaks not only to his fascination with nature “wasting itself, not living up to its potential but reveling in a profusion of non-realizable possibilities” 32, but also less anthropocentric or more biocentric ways of characterizing modern play. Translating homo ludens to “man playing” already diverts focus from the person or subject who plays to the act of play itself, in an echo of Sarah Kember and Joanna Zylinska’s call to rethink media studies less as the analysis of media objects than the study of processes of mediation.33 But it is natura ludens that truly augurs the as yet unrealized promise of digital vegetal play.

”Instance the Crap Out of Them”: Digitally Recreating the Shoshone Wilderness for Firewatch

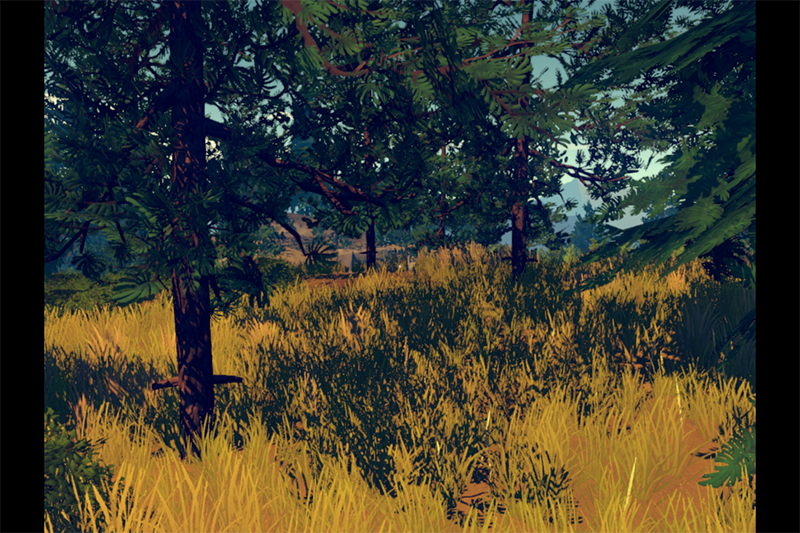

In early 2016, the small San Francisco-based studio Campo Santo released an artful walking adventure game called Firewatch, marketed as a “single-player first-person mystery.” In it, you play as Henry, a middle-aged, slightly overweight man reeling from a failed marriage who takes refuge in work as a summer fire lookout in Wyoming’s Shoshone wilderness. The game unfolds over 13 playable/79 elapsed days in the year 1989, and as Henry investigates a series of mysterious happenings in the forest around his tower, he builds an ambiguous rapport with his supervisor Delilah, with whom he communicates only via walkie-talkie (the game itself could be described as a “walkie-talkie”). Firewatch received a number of industry awards for its art, script, voice acting, and so on, and from an environmental media perspective, the game is worth close scrutiny on several levels. Not only did Campo Santo employees consider camping trips and detailed study of Forest Service schematics as legitimate design research, but the game’s players have frequently remarked that playing the game feels like walking and working in a real national forest (Figure 2).34 Firewatch also presents a rare opportunity to peer inside the culture and technical exigencies of environmental art design in video games, as the game’s lead artist, Jane Ng, has spoken on numerous occasions about the challenges of creating Firewatch’s distinctive open world. In her hour-long presentation at the 2016 Game Developer’s Conference, during which she talks extensively about vegetation design, Ng’s somewhat sheepish justification is that “Trees take up more than half the screen during most of the game, so it seems worthwhile to talk about.”35

Ng’s experience in fabricating the natural landscape of Firewatch will help me to explore two final points in relation to digital botanical modeling: first, the outwardly puzzling claim made by several leaders in the 3D plant industry that their software permits “modeling ‘by hand’,” and second, the entrenched benchmark of photorealism. As we shall see, the prepackaged algorithms of 3D modeling software do not entirely proscribe artistic intervention, and although most users of SpeedTree and its competitors see realism as the gold standard, both experts in digital botanical modeling and the art team at Campo Santo have demonstrated that the expressive capacities of their tools exceed this normative goal.

Modeling “by hand”

SpeedTree was not available when Ng started work on Firewatch, and after finding the game engine Unity’s built-in Tree Creator tool to be too limiting, she decided to make her own trees for the game. Although there are 4,600 individual tree placements in Firewatch, not including “billboards” (lower-detail backdrops used for distance viewing), Ng only created 23 distinct types of trees, and of those 14 constitute the bulk of the visible forest. Not surprisingly, given that all 3D game artists must reconcile the desire for stunning visuals with the limited processing speeds of players’ computers, Ng’s GDC talk was liberally peppered with the language of optimization, from tips for aspiring designers (“model variety is overrated!” or “There is no reason to load in assets you do not need!”) to appreciation for low-resolution shortcuts and “cheap” geometry. 3D artists like Ng commonly discourse in terms of “tris,” or polygons, since too many models with high triangle counts, though beautiful, may stop a computer in its tracks when it comes time to render the models into interactive images. Ng unabashedly praises modularity over copious unique assets, at one point admitting that “there was a lot of copying and pasting going on in Firewatch,” followed by the aside, “that’s kind of my philosophy actually, just to make a few really good modules and just instance the crap out of them because they wouldn’t really notice.” Part of the rationale, then, is that they (hypothetical players) are unlikely to perceive a lack of vegetal variety. Costly visual detail is cunningly reserved for portions of the game world that the player is apt to notice—the base of trees (Ng added more detail there with broken branches and richer textures) (Figure 3), ground-level shrubbery, and generally what occupies the player’s field of view, particularly in close proximity. Thus the forest of Firewatch is what Ng calls “open world-ish,” delivered through “world streaming” based on “player adjacency.” In essence, this means that the game world is being selectively loaded and unloaded depending on the player’s sightlines, literally vanishing behind boulders or the player’s back as he or she hikes to the next landmark. In a similar vein, one of the senior artists at IDV/SpeedTree, Sonia Piasecki, has trained clients to “model for the shot.”36 Customers can economize on triangle count by reserving detail for only those aspects of a tree that face one’s virtual camera, leading to SpeedTrees with lush front ends and comparatively barren back ends!

Yet although practical recommendations such as these appear ripe for critique in terms laid forth by both Frosh and Gabrys, such critique would miss the curious interplay between human and machine, hand and algorithm, evident in digital vegetal design. Some have even jokingly compared 3D plant artists to digital botanists, arborists, or even silviculturists, depending on the scale (individual or mass) and intent (scientific or aesthetic) of their virtual plant care. Less human-centered production is not limited to game design—British architectural theorist Neil Leach has outlined a comparable process, which he also terms digital morphogenesis. In a 2009 piece in Architectural Design, Leach describes architecture’s shift away from literary postmodernism and the theories of poststructuralism toward a twenty-first century fascination with scientific and technological fields, more consonant with traditional structural engineering, biology, or materials science than aesthetics.37 Leach also describes the architect’s role as shifting away from being the creative impetus or genius that dictates design and uses computers only as modeling tools, to being the one who just sets loose guidelines around emergent or generative processes drawn from nature and unleashed in digital software. For Leach, this is architecture’s “performative” turn, in the sense of emphasizing a structure’s function or performance rather than its appearance, or process over representation.

These recent currents in architecture and engineering, particularly those with a strong interest in biomimicry, help explain the appeal of digital botanical design software and practitioners’ odd blending of parameterization and hand-tweaking—put plainly, 3D plants are computer generated, and then some. As Geoffrey Batchen has observed about the presumed death of photography at the hands of computer-driven digital imaging processes, “As their name suggests, digital processes actually return the production of photographic images to the whim of the creative human hand (to the digits). For that reason, digital images are actually closer in spirit to the creative processes of art than they are to the truth values of documentary.”38 Yet there are still important differences between wandering virtual worlds populated by vegetable readymades, or by plants that germinate, grow, wither, and die, or respond phenologically to changing temperatures, seasons, light patterns, and the proximity of other things. Research is, for instance, already underway on digital trees that adapt to the presence of built objects, by growing away from obstacles or responding appropriately to gravity and light.39 Today, SpeedTree’s competitors Xfrog and Laubwerk (both affiliated with Dr. Oliver Deussen) try to distinguish themselves by stressing that their software rests less on mathematical shortcuts (such as fractals) than plant science. In their view, because SpeedTree strives to give full directorial control to its clients in the movie and games industries, it matters little if it bends or breaks “botanical rules.” These tensions between artistic license and scientific accuracy, or between what Leach might call top-down, explicitly determined geometries and bottom-up, “form-finding” processes, will likely always haunt the practice of computer modeling.

Nonphotorealistic rendering and expressive modeling

Going forward, a more nuanced approach to digital vegetation will need to separate the demands of photorealism from those of botanical realism. Although they relegate them to the final chapters of their book, Deussen and Lintermann credit media artworks such as Bill Viola’s “The Tree of Knowledge” (1997) as primary motivations, while conceding that research into nonphotorealistic rendering methods or more “synthetic” plant models remains underdeveloped. Even SpeedTree artist Piasecki, when asked to list her favorite game trees, commends those that made more innovative, or unexpected, use of IDV’s tools.40 Admissions like these imply that the telos of digital plant modeling could be shifted to more imaginative ends. Again, Firewatch serves as an instructive example. In the game, although trees near Henry are rendered realistically, trees seen at a distance purposefully look more stylized—Firewatch’s art director Olly Moss wanted them to resemble the game’s marketing imagery, which was directly inspired by New Deal-era National Park Service posters. Rather than being seen as visually deficient, these forested landscapes are designed to evoke another era, and transform the game into a mixed-media mode reminiscent of graphic art. Nicole Starosielski has likewise argued that animation is not a poor substitute for non-fiction film about the environment, as animation has a unique capacity to dramatize environmental fluidity and otherwise imperceptible alterations.41

Alexander Galloway has usefully ported theories of realism generated in the domains of literature and art to the world of video games, concluding that narrative and representational realism are not the same thing. For him, “realistic-ness” describes the game industry’s unceasing and largely asymptotic quest to achieve graphical fidelity to real life, evidenced in countless back-of-box claims and the recent resurgence of virtual reality (or “VR”) platforms and experiences.42 In contrast, Galloway suggests that we might evaluate game “realism” not in terms of polygon count but on the basis of the game’s correspondence to a player’s lived social reality. Thus a game like The Sims is for many more real than a first-person military shooter like Call of Duty, because more of us are familiar with the quotidian experience of managing a household than working as military operatives. Acknowledging that realism often carries a social edge in other media, Galloway ultimately suggests that game scholars “turn not to a theory of realism in gaming as mere realistic representation, but define realist games as those games that reflect critically on the minutia of everyday life, replete as it is with struggle, personal drama and injustice.”43 In the context of this essay, we might speculate whether Galloway’s theory of social realism could encompass non-player-centered or non-social aspects of gameplay, from the game world itself to the player’s interactions with the other-than-human. Certainly, our movement through space and time is not only defined by our interactions with other people, and on a planet currently grappling with the long-anticipated consequences of global warming, “struggle, personal drama and injustice” are equally apt descriptors of gross environmental inequalities.

While this all only begins to scratch the surface of computer-generated natural objects, the challenge is to stick fast somewhere between outright condemnation of simulation and uncritical absorption in the technical intricacies of digital design. To study virtual flora, we might take as directives both Carla Hustak and Natasha Myers concept of “an affective ecology shaped by pleasure, play, and experimental propositions”44 and Marder’s call “to live and to think in and from the middle, like a plant partaking of light and of darkness.”45 After all, the materiality of a SpeedTree is lodged not only in silicon and plastic, but also the carbon and water of living trees—somewhere between soil and sky, computer and cloud.

Footnotes

-

Jennifer Gabrys, Digital Rubbish: A Natural History of Electronics (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2013): 84. ↩

-

“All Time Box Office,” Box Office Mojo, accessed November 28, 2019, https://www.boxofficemojo.com/alltime/world/. ↩

-

Daniel Terdiman, “ILM steps in to help finish ‘Avatar’ visual effects,” CNET.com, December 19, 2009, https://www.cnet.com/news/ilm-steps-in-to-help-finish-avatar-visual-effects/; “SpeedTree ™ in Avatar,” accessed September 4, 2018, https://store.speedtree.com/downloads/Avatar_User_Profile.pdf. ↩

-

“SpeedTree Vegetation Modeling,” accessed September 4, 2018, https://store.speedtree.com/. Middleware typically refers to software that bridges between a computer’s operating system and its applications, although in this case it likely refers to SpeedTree’s integration into something like a game engine, used to develop games, in order to add vegetation-specific functionality. ↩

-

Steve Dove, “The Academy’s 2015 Sci-Tech Awards – Winners List,” February 9, 2015, accessed September 4, 2018, http://oscar.go.com/news/oscar-news/150209-ampas-sci-tech-awards-2015-winners. Interestingly, 2015 also saw a Technical Achievement Award for the designers of the DreamWorks Animation Foliage System, for its role in “creating art-directed vegetation in animated films for nearly two decades.” ↩

-

“SpeedTree® 8 for Lumberyard,” accessed September 4, 2018, https://store.speedtree.com/store/speedtree-for-lumberyard/. ↩

-

Emanuel Maiberg, “How to Win an Academy Award for Planting Trees in Video Games,” Motherboard, January 20, 2015, https://www.vice.com/en_us/article/ezvq7n/video-game-arborists. ↩

-

Kristen Whissel, Spectacular Digital Effects: CGI and Contemporary Cinema (Durham: Duke University Press, 2014). ↩

-

A brief discussion of digital morphogenesis can also be found in my book, Playing Nature: Ecology in Video Games (University of Minnesota Press, 2019). ↩

-

Przemyslaw Prusinkiewicz and Aristid Lindenmeyer, with James S. Hanan, F. David Fracchia, Deborah Fowler, Martin J. M. de Boer, and Lynn Mercer,The Algorithmic Beauty of Plants (New York: Springer-Verlag, 1990). ↩

-

Oliver Deussen and Bernd Lintermann, Digital Design of Nature: Computer Generated Plants and Organics (Berlin: Springer Verlag, 2010), 43. Xfrog began as Greenworks Organic Software in the 1990s, when Deussen and Lintermann sought to translate their research into publically accessible software. Their early collaborator Stewart McSherry has run the company since 1996. ↩

-

Ibid., 2. ↩

-

Ibid., 19. ↩

-

Michael Marder, Plant-Thinking: A Philosophy of Vegetal Life (New York: Columbia University Press, 2013): 128. ↩

-

Paul Frosh, The Image Factory: Consumer Culture, Photography and the Visual Content Industry (Oxford: Berg, 2003). ↩

-

Ibid., 200, Frosh’s emphasis. ↩

-

Emma Marris, Rambunctious Garden: Saving Nature in a Post-Wild World, (New York: Bloomsbury, 2011). ↩

-

Lorraine Daston and Peter Galison, Objectivity (New York: Zone Books, 2007). ↩

-

Marder, Plant-Thinking, 186. ↩

-

Frosh, The Image Factory, 198-9. ↩

-

Cory Doctorow, ©ontent: Selected Essays on Technology, Creativity, Copyright, and the Future of the Future (San Francisco: Tachyon Publications, 2008). ↩

-

Lisa Parks, “Around the Antenna Tree: The Politics of Infrastructural Visibility,” Flow 9.08, http://www.flowjournal.org/2009/03/around-the-antenna-tree-the-politics-of-infrastructural-visibilitylisa-parks-uc-santa-barbara/. ↩

-

Maiberg, “How to Win.” ↩

-

Gabrys, Digital Rubbish, 58. ↩

-

Ibid., 86. ↩

-

Ibid., 84. ↩

-

Marder, Plant-Thinking, 76-7. ↩

-

R. Schmid and A. Farjon, “Sequoiadendron giganteum (Bigtree, Giant Sequoia, Sequoia, Sierra Redwood),“The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2013, accessed September 5, 2018, http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2013-1.RLTS.T34023A2840676.en ↩

-

Marder, Plant-Thinking, 130. ↩

-

Marder, Plant-Thinking, 144. ↩

-

Johan Huizinga, Homo Ludens: A Study of the Play Element in Culture, trans. R.F.C. Hull (London: Routledge, 1949). ↩

-

Marder, Plant-Thinking, 145. ↩

-

Joanna Zylinska and Sarah Kember, Life After New Media: Mediation as a Vital Process (Cambridge, MIT Press, 2012). ↩

-

Firewatch even shows up on Loose Leaf, the official blog of the American Forests conservation organization: https://www.americanforests.org/blog/firewatch-video-game/. ↩

-

Jane Ng, “Making the World of Firewatch,” Game Developers Conference, March 14-18, 2016, GDC Vault, https://www.gdcvault.com/play/1023191/Making-the-World-of. ↩

-

Sonia Piasecki, “Tips for Modeling a High Detail Tree,” January 24, 2013, accessed September 5, 2018, https://store.speedtree.com/high-detail-tree-modeling-tips/. ↩

-

Neil Leach, “Digital Morphogenesis,” Architectural Design, January 16, 2009: 32-7, https://doi.org/10.1002/ad.806. ↩

-

Geoffrey Batchen, “Ectoplasm: Photography in the Digital Age,” in Over Exposed: Essays on Contemporary Photography, ed. Carol Squiers (New York: The New Press, 1999): 15. ↩

-

O. Stava, S. Pirk, J. Kratt, B. Chen, R. Měch, O. Deussen, B. Benes, “Inverse Procedural Modelling of Trees,” Computer Graphics Forum 33, no. 6: 118-31, https://doi.org/10.1111/cgf.12282. ↩

-

Nathan Grayson, “The Best Video Game Trees, According To Someone Who Makes Them,” Kotaku Australia, March 25, 2018, https://www.kotaku.com.au/2018/03/the-best-video-game-trees-according-to-someone-who-makes-them/ ↩

-

Nicole Starosielski, “‘Movements that are drawn’: A history of environmental animation from The Lorax to FernGully to Avatar,“the International Communication Gazette 73, no. 1-2 (2011): 145–63, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/1748048510386746. ↩

-

Examples include (for Xbox One) Grand Theft Auto V’s “Features across-the-board graphical and technical enhancements for a deeper, more vibrant world” and my personal favorite, Forza Motorsport 5’s “Unprecedented visual realism | An all-new graphics engine delivers air you can taste and texture you can feel at 1080p resolution and 60 frames per second.” ↩

-

Alexander R. Galloway, “Social Realism in Gaming,” Game Studies 4, no. 1 (November 2004), http://www.gamestudies.org/0401/galloway/. ↩

-

Carla Hustak and Natasha Myers, “Involutionary Momentum: Affective Ecologies and the Sciences of Plant/Insect Encounters,” differences: A Journal of Feminist Cultural Studies 23, no. 3: 78, doi 10.1215/10407391-1892907. ↩

-

Marder, Plant-Thinking, 178. ↩

Cite this article

Chang, Alenda Y. "Between Plants and Polygons: SpeedTrees and an Even Speedier History of Digital Morphogenesis" Electronic Book Review, 15 December 2019, https://doi.org/10.7273/wtdf-7w30