E-Lit's #1 Hit: Is Instagram Poetry E-literature?

Like e-books and so much else in digital commerce, the poetry printed out by Instagram give us back the book - stripping away the social features such as reader comments, nested conversations and responses that make a work "viral," or "spreadable." The content of Instagram poetry, to nobody's surprise, is almost always simplistic, inspirational, and emotional. What it spreads. like any other social media, is indistinguishable from from the surveillance infrastructure of digital metadata that allows algorithms to "read" the reader (who is left in the dark). Kathi Inman Berens in this essay puts forward some ways to change that.

If ever there were e-literature that could fill a stadium, it’s Instagram poetry.⏴Marginnote gloss1⏴See Leonardo Flores’essay, published in ebr, where he recognizes “the need to account for the explosive growth and diversification of e-literary digital writing practices beyond what is practiced and studied by the ELO community.”

— ebr Editors (Apr 2019) ↩

This essay, which I presented on the panel “Toward E-Lit’s #1 Hit” at the Electronic Literature Organization 2018 conference in Montréal, responds to Matthew Kirschenbaum’s keynote at the prior year’s conference. Kirschenbaum traced the coincident development of stadium (“Prog”) Rock–specifically Electric Light Orchestra–and electronic literature, a twinning that led some of us to speculate about what might constitute massively popular e-literature, its “#1 hit.”

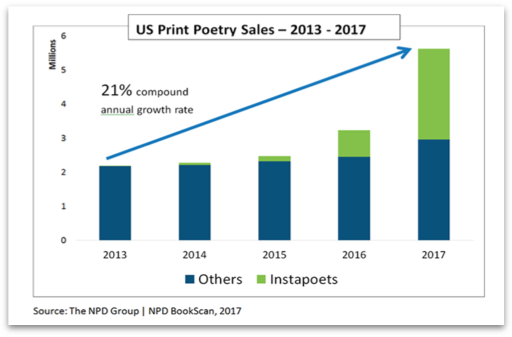

Formally more akin to a greeting card than traditional poetry because of its sentimentality and combination of text and image, Instagram poetry is a book publishing phenomenon, accounting for a stunning 47 percent of all the poetry books sold in the United States in 2017. Whether it is the top seller, Rupi Kaur, with her pen-and-ink feminist drawings and confessional verse, or R.M. Drake, whose Insta profile announces “$12 FOUR BOOK BUNDLE BACK IN STOCK: link below,” or the handwritten-on-parchment and IBM Selectric typewriter aesthetic of Tyler Knott Gregson, Instapoetry is simplistic, little more taxing than reading a meme. It is almost always inspirational or emotional. Printed books of Instapoetry collect exactly the same content accessible for free in the Instagram app. Printed volumes eliminate the social features of the app such as reader comments, nested conversations, and quantification of reposts and likes. In this sense, printed Instapoetry is more like traditionally printed poetry because it is deliberately sequenced in book form and stripped of the social features that make it “viral,” or “spreadable.” In Spreadable Media, Jenkins, Sam Ford and Joshua Green critique the metaphor of virality as too passive, undercutting fan agency in spreading content they like. Jenkins, Ford and Green suggest instead that massively shared content is like peanut butter: “content that remains sticky even as it’s spread” (9). Instagram poetry is peanut butter.

Year-over-year annual poetry sales indicate a walloping 21% annual compound growth rate since 2013, a growth corresponding with when Lang Leav self-published the first volume of printed social media poetry Love and Misadventures, which originally appeared in Tumblr (NPD, 2018). Rupi Kaur’s début volume of printed Instapoetry, milk and honey sold three million copies worldwide and has been translated into twenty-five languages. NPD Group [formerly Nielsen Bookscan] reports 2,067,164 copies of milk and honey sold as of 9 January 2019. This figure does not include Amazon sales, which Amazon never shares. In 2017, Kaur’s second volume the sun and her flowers outsold #3 on the poetry bestseller list, Homer, at a ratio of 10:1. But the hits are not just by Kaur: Instapoets comprised twelve of 2017’s top twenty bestselling poets. That’s 60% of bestsellers in a publishing field that had been considered moribund.

Instapoetry is definitely a #1 hit. But is it e-literature?

More precisely, can a literary work be e-lit if it’s not self-consciously engaged in the aesthetic of difficulty that characterizes e-literature’s first and second generations?

While I am persuaded by Leonardo Flores’s argument that there’s a wealth of digital creative production among people who have never heard of ELO nor studied e-lit in college, I wonder if the radical expansion of e-lit’s aesthetic from difficulty to ease violates one of e-literature’s founding principles: that to read e-lit requires “non-trivial” effort, whether that effort is physical interaction and/or cognitive complexity? This 1997 definition from Espen Aarseth’s Cybertexts, and N.Katherine Hayles’ definition of technotexts (2002) describe the mechanics by which e-lit artists align its practices with modernist poetry, not populist bestsellers. Our field remains committed to self-conscious reading practices, where the interaction between a work’s physical properties and its semantic strategies engage in “reflexive loops” (Hayles). Stephanie Strickland suggests that “reading e-lit requires taking an aesthetic attitude toward the textscape as an object that stimulates the sense. To read e-works is to operate or play them (more like an instrument than a game, though some e-works have gamelike elements)” (2009). An experimental, hand-built interface is very different from a pre-packaged, self-evident social media interface. In this essay, I explore whether or not Instapoetry participates in the defined aesthetics of electronic literature, and I argue that Instagram poetry’s aesthetic is indivisible from the surveillance capitalism infrastructure of social media metadata that makes algorithms agentic in “reading” the reader.

I conceptualize Instapoetry as a watershed moment in bibliography, where scholars writing about digital literary interactivity must reckon not only with the gestures we can see—the “likes,” comments, reposts or “@s”—but the platform code and data harvesting we cannot see. Perhaps we could agree that a “like” is “trivial” engagement. But what about the terabytes of data shed by and then harvested from Instapoetry fans? It cannot be “trivial” when 160,000 people “touching” just one Instapoem leave behind so much information that is quite literally out of their hands - is, in fact, a loss they can neither feel nor tally?

Instapoetry is especially interesting generically because “poetry” connotes the pinnacle of the literary highbrow. Poetic language is the most condensed and figurative of literary modes and there’s a special wing of the Interwebs devoted to explaining why poetry is so hard to understand, items like “how to read poetry like a professor” (hint: reread) and David Biespeil’s list of “Ten Things Successful Poets Do.” Number one: “embrace toxicity”; number two: “assume the worst”; number three: “Let negative thoughts hijack [your] brain,” and so forth (2013). Poetry, since the early twentieth century moderns, has been a difficult business, both in the reading and making: think Pound’s debt to Chinese ideograms, and Eliot’s endnotes to The Waste Land, which reviewers at the time found both necessary and risible. It’s no wonder there are guides today on Goodreads for how to make poetry less intimidating.

It is into this highbrow literary context that printed Instagram “poetry” became a phenomenon in 2013 when Lang Leav, a woman born in a Thai refugee camp, sold the rights to her self-published book Love and Misadventures to Andrews McMeel Publishing, who sold cookbooks, gift books and comic strip collections until Instapoetry made its fortune. AMP understood the value proposition of moving Love and Misadventures onto their roster, and Leav, whose 5000-unit print-run sold out in a week, understood she needed help to meet demand.

It’s worth lingering over how self-publishing a poetry book is different from self-publishing poetry via a social media website like Tumblr or Instagram. The most salient difference is in the type of capital that circulates in these transactions. Reposts, likes and comments are the currency of social media, where the financial value of those transactions is harvested by media platforms, not the authors. Every form of interaction, from simply seeing the post in one’s feed (“lurking”) to reposting it with a comment sheds reader data that becomes volumetric with each increased level of engagement.

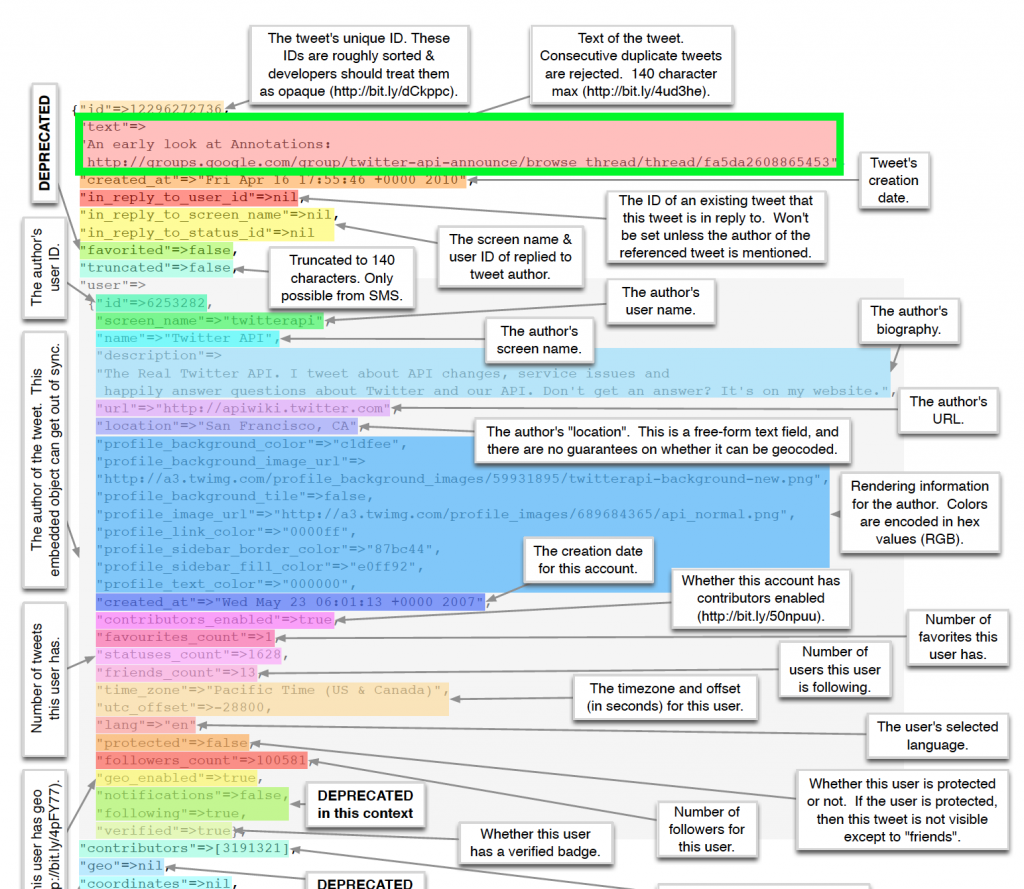

Think of the information on the user interface–that is, what the reader engages with on the screen–as the informational tip of the iceberg: the vast majority of data in any social media post is, like an iceberg, hidden from view.

This visualization annotates a Tweet’s metadata, which indicates the types of information Twitter collects on a single Tweet. Please keep in mind this is the Paleolithic era of Twitter, circa 2010. I’ve boxed in green near the top of the image the actual tweet that users would have seen in their feeds. The rest of the metadata is the invisible bulk of the iceberg. This is sheerly descriptive metadata. It is not the code that moves packets of information from author to device to server and out through a vast, dispersed distribution system.

It’s interesting that this annotated metadata of a 2010 tweet is a rare disclosure of metadata that the company collects. Obviously, a lot has changed for Twitter since 2010. For example:

- The text count has doubled to 280 characters;

- Tweets now embed images & short videos;

- Tweets harvest much more precise GPS data, down to what aisle one is standing in at a store.

- Bots, hate speech and “dog whistles” are effects of the platform, although Twitter is attempting to crack down on this.

A more recent analysis of Twitter metadata (Barrero 2017) includes new classes such as Klout scores, sentiment and “sentiment category probability,” emotion and “emotion category probability.” This is a very basic view of contemporary social media metadata. The focus on emotion and sentiment is raw data for behavioral marketing. What Flores has dubbed “Third Generation E-literature” is inextricably co-constituted with such metadata, which is to say, engaging its literary and artistic meaning comes at the cost of shedding behavioral data that is collected, collated, and auctioned. Reading e-literature in this context inscribes the reading with acts of commercial marking that are locked away from the reader and visible to the human and nonhuman agents gathering and auctioning such information. In The Metainterface – The Art of Platforms, Cities and Clouds, Christian Ulrik Andersen & Søren Bro Pold track what it means that “today’s cultural interfaces disappear by blending immaculately into the environment” (10) and propose net art and e-literature as materially self-conscious practices that reveal “fissures” in “habitual” (159) ubiquitous computing. What is the “metainterface’? It’s the movement of human/computer interaction from the desktop to the smartphone and cloud. Humans are both agents and quarry, where they use smartphones to electively inscribe themselves on the network, but also shed enormous quantities of data harvested by media companies such as Facebook and Google. Instapoetry is the alluring blossom that attracts users’ attention and engagement. Such readers’ social media wanderings pollinate sites with data both shed and accumulated. The datafication of reader response is an essential part of the poem, one whose effects are visible to readers only indirectly in ads prompted by the reader’s engagement with the poem. This is a new kind of “reader response,” where algorithms are agentic: the human reader is herself “read” by behavioral targeting algorithms, parsed for commercial susceptibility, and served new information or ads designed to entice transaction, even if that transaction is only a click.

Let’s take a look at Instapoetry in the wild. This is one poem by Rupi Kaur about the Trump administration’s policy of separating refugee families at the United States border.

Kaur, speaking as an immigrant, excites a lively discourse in multiple spoken languages and emoji, a visual communication format underwritten by Unicode and meant to provide “all the characters needed for writing the majority of living languages in use on computers” (W3C, quoted in Reed). The blend of spoken word and emoji is characteristic of the types of populist formats of 3rd generation electronic literature. Instagram organizes conversation into a time-stamped database too large for humans to read closely. Sample selection delivers a snippet of a political debate about whether incarcerating children is a just implementation of U.S. immigration law. The problem for literary critics or book publishing scholars who are taking the measure of this kind of discourse is how to cull evidence and make the case for exemplarity when the dataset is so large? Some of the tools of distant reading [most frequent word counts or co-locations] are only so good as the query. How to measure significance in an environment of rapidly proliferating superabundance, where hundreds of thousands of pieces of data are created each day – and that’s just what’s visible on the user interface, let alone the volume of invisible but material metadata sparked by each digital touch.

In the case of Instagram comments, to stabilize the data is to denature it.

To take the measure of Instagram as a platform for electronic literature, consider Shelley Jackson’s SNOW, a sequential text/image poem where each of the 428 lexia is hand-drawn with sticks and brushes to look like type pressed into snow in various stages of melt and drift. SNOW is a time-based work. Its first lexia was published January 22nd 2014 and most recent was published, at time of writing this essay, April 6, 2018. The still-in-progress poem cuts off mid-sentence.

There are several aspects of SNOW that mark its second-gen e-lit aesthetic. First, it has reading instructions: “A story in progress, weather permitting. (Read in reverse order.)” Five of twenty-four comments on the first lexia also instruct others how to read it. Second, SNOW repays close reading. Anna Nacher, Søren Pold and Christian Ulrik Anderson, and Scott Rettberg have all prepared conference papers or published work about SNOW. Third, Jackson’s status as a vaunted first-gen e-literature artist imbues SNOW with literary prestige. Patchwork Girl is the second most frequently cited work of electronic literature, according to Jill Walker Rettberg’s distant reading of dissertations about electronic literature. Jackson’s reputation casts a highbrow aura of modernist difficulty despite this poem being set in a populist platform. Fourth, Jackson disengages from the circulation of social capital on Instagram. She treats the Instagram platform as a printing press that distributes a hand-drawn emulation of machine writing. Jackson does not respond to comments posted to lexia, nor does she “like” or repost them. The profile picture of Jackson in winter coat bending over a snow bank like a scribe leaning over vellum reinforces the materiality and ancient human labor of her endeavor. The profile picture frames Jackson in the act of writing. She is resolutely removed from the scene of reading, making SNOW categorically different from Instapoetry where authors interact with fans.

Aesthetically, SNOW has more in common with Jim Andrews’ “Seattle Drift” (1997) than Instapoetry. As is the case of the one-word lexia in SNOW, each of the div tags in “Seattle Drift*”* holds one word of the poem. In the code comments of this visual, kinetic poem, Andrews says of “Seattle Drift”:

Stylistically … the text talks about itself. I like this approach because it focusses [sic] attention on the questions and also allows me to develop character. The character is the text itself [my emphasis].

Both Jackson and Andrews are interested in the autonomous behavior of text, whether machine-mediated or snow-mediated. For them, text is a nonhuman “character,” and “drift” is a pivot point of interactivity. Andrews’ poem begs the reader to make it drift, to “do me.” For Jackson, drift is non-interactive. Snow and climate, not humans, are the agents influencing drift and display. Visually the poem reinforces snow’s way of looking like a blank page awaiting inscription; but unlike the nineteenth-century British male romantic poets, for whom nature was a handmaiden to their own poetic expression, SNOW is a page that resists human inscription by melting.

On the surface, assessing digital-born Instapoetry through close reading as I’ve just done with SNOW and “Seattle Drift,” Instapoetry seems not to be a technotext. But ludostylistic scholarship gives us tools for reading Instapoetry’s bibliographic code. Calling upon us to “keep in view the need to let go of the object-centered approach that is at the heart of book history,” Johanna Drucker articulates a vision of book history that decenters the book as object and considers instead the logics by which a book is an “event space.”

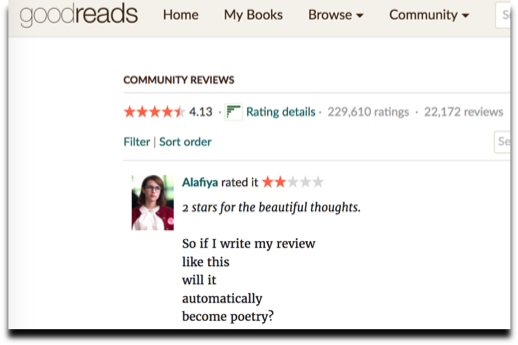

Book publishers have found a way to extract extraordinary financial value from printed Instapoetry as a dynamic playable event space. While social media capital is a routine part of any book marketing campaign, and influences which authors are or are not offered publishing contracts, converting social media capital into sales remains hard to correlate. In Instapoetry, book publishers have a direct conversion of social media capital to financial capital. Unlike other social media celebrities such as YouTube personalities, Instapoets don’t face the awkward task of converting a fanbase from one medium (vlogging) to another (printed books). Printed Instapoetry shifts the “content” seamlessly from digital to print. But stripped of liveness, printed Instapoetry ends up looking banal. Its treacly insights, absent the warm glow emanating from fans inside the app, hardens into branding. This Goodreads review, visible on the first page of returns, sums up the skepticism Instapoetry can evoke outside the app:

I’ve argued in various contexts that even in physically interactive collaborative poetry such as The Poetry Machine and virtually interactive literary games like netprov (see my “Live/Archive” essay), printed or archival repositories of live experience always distort the live experience. Nothing, neither digital traces nor printed artifacts, replicates liveness. But that doesn’t stop us from wanting mementos of pleasurable live experience: think about the enormous market for live music “merch” such as concert t-shirts, hats, programs, shot glasses. A printed book of Instagram poetry is also a souvenir, though one stripped of playfulness in a dynamic event space like the Instagram app. Nevertheless, printed poetry books participate in the ongoing flow of play and comment by stopping the flow, performing that it’s possible to stop paddling in digital currents.

The bibliographic intervention I propose layers a new valence onto “play” where gestural interactivity is foundational, but not the primary object of study. This would be a new turn in ludosemiotic scholarship. Commenting on the book as a physical medium, Serge Bouchardon notes that “With the Digital, it is not only the medium, but the content itself which becomes manipulable. Manipulability is the very principle of the Digital” (25). Katarzyna Bazarnik defines Liberature as specifically _“a Book-bound Genre … _better understood as ‘expanded’ literature, aware of its spatial, embodied nature” (43). Agnieska Przybyszewska suggests that liberature is not a genre, but can be classed according to gradations of physical play that transpire both within and outside the printed book format, such as in mobile electronic literature (her monograph Liberackość dzieła literackiego is cited and discussed in Bazarnik, particularly 103-4). Astrid Ensslin, in Literary Games (2014), situates works on quadrants where physical play is relative to literary ambiguity. Alexandra Saemmer has speculated that the intensity of physical touch in a digital-born literary work affects the reader’s process of identification with the protagonist. These and other scholars of ludosemiotics, including Amaranth Borsuk’s recent The Book in the M.I.T. Press “Essential Knowledge” series, use close reading techniques to consider how play and physical manipulation influence how we read literature.

What I’m proposing is slightly different.

A book of printed Instapoetry is not like a gem in a setting that is somehow lifted up and out of the data-harvesting context. Instead, such a book is brought into being by the social media transactions that make Instapoetry phenomenal - even as the printed volume seems to offer respite from tracking and behavioral marketing. In fact, the site of tracking and reader datafication shifts from the social media platform to the book distributor, whether it’s Amazon or a brick-and-mortar bookseller. Even books purchased anonymously with cash are still tracked as sales. The reader being converted into a datastream is not a byproduct of reading poetry. It is part of the poem itself. As we think about the memetics of Third Generation electronic literature, an aesthetic inextricable from tactical media and surveillance capitalism, we ask: What does it mean that the first highly profitable digital-born literature, Instagram poetry, makes its money in the walled gardens of the “post-Web” in ways we can only imagine because the code on which those proprietary social media platforms are built is not inspectable, even to government regulators?

Nick Montfort asks: “What has happened to Hypertext in the post-Web world?

Just to stick to Twitter, for a moment: You can still put links into tweets, but corporate enclosure of communications means that the wild wild wild linking of the Web tends to be more constrained. Links in tweets look like often-cryptic partial URLs instead of looking like text, as they do in pre-Web and Web hypertexts. You essentially get to make a Web citation or reference, not build a hypertext, by tweeting. And hypertext links have gotten more abstruse in this third, post-Web generation! When you’re on Twitter, you’re supposed to be consuming that linear feed — automatically produced for you in the same way that birds feed their young — not clicking away of your own volition to see what the Web has to offer and exploring a network of media.

I began this research project wondering why people would pay $13 for a book that reprints exactly the same content that can be had for free, on-demand, in the Instagram app. Why buy the book? Now I understand that printed Instagram poetry wouldn’t be a phenomenon without its origin in post-Web, walled-garden engagement. Is Instapoetry e-literature? Yes. The performative materiality of social media platforms reshapes the contemporary literary field. The e-lit aesthetic of difficulty moves from close reading the medium-specificity of first and second generation works, to skimming the content and close reading the promiscuous read/write capacities of social media metadata, and guessing at the black-boxed code that undergirds 3rd generation e-lit.

Works Cited

Anderson, Christian Ulrik and Søren Bro Pold. The Metainterface: The Art of Platforms, Cities and Clouds. Cambridge, MA: The M.I.T. Press. 2018. Book.

Andrews, Jim. “Seattle Drift.” Vizpo [personal website]. 1997. http://www.vispo.com/animisms/SeattleDrift.html

Barrero, Carlos. “The Metadata from a Single Social Media Post.” 2 October 2017. https://www.crimsonhexagon.com/blog/metadata-from-a-social-media-post

Bazarnik, Katarzyna. Liberature: A Book-bound Genre. New York: Columbia University Press. 2018. Book [U.S. distribution of original publication by Jagiellonian University Press, 2016].

Berens, Kathi Inman. “Live/Archive: Occupy MLA.” Hyperrhiz: New Media Cultures, vol. 11. Spring 2015. http://hyperrhiz.io/hyperrhiz11/essays/live-archive-occupy-mla.html

Biespiel, David. “Ten Things Successful Poets Do.” The Rumpus. 2013. https://therumpus.net/2013/12/david-biespiels-poetry-wire-10-things-successful-poets-do/

Bouchardon, Serge. “Mind the Gap! 10 Gaps for Digital Literature?” Keynote presentation at the 2018 Electronic Literature Organization Conference. Montréal. http://www.utc.fr/~bouchard/Bouchardon-ELO18-English.pdf

Borsuk, Amaranth. The Book. Cambridge, MA: The M.I.T. Press. 2018. Book.

Drucker, Johanna. “Distributed and Conditional Documents: Conceptualizing Bibliographical Alterities” in MATLIT: Materialities of Literature. 2014. http://impactum-journals.uc.pt/matlit/article/view/1891/1270

Ensslin, Astrid. Literary Gaming. Cambridge, MA: The M.I.T. Press. 2014. Book.

Jackson, Shelley. SNOW. https://www.instagram.com/snowshelleyjackson/ 2014-present.

Jenkins, Henry, Sam Ford and Joshua Green. Spreadable Media: Creating Value and Meaning in a Networked Culture. New York: NYU Press. 2013.

Kaur, Rupi. milk and honey. Kansas City: Andrews McMeel Publishing. 2016. Book.

_____. “you split the world into pieces” Instagram. June 19, 2018. https://www.instagram.com/p/BkOyGTxlAWf/

Kirkorian, Raffi. “Map of a Twitter Status Object.” The Wall Street Journal. 18 April 2010. http://online.wsj.com/public/resources/documents/TweetMetadata.pdf

Kirschenbaum, Matthew. “ELO and the Electric Light Orchestra: Lessons for Electronic Literature from Prog Rock.” Keynote at the 2017 Electronic Literature Organization conference. Porto, Portugal.

Montfort, Nick. “A Web Reply to the Post-Web Generation.” 26 August 2018. https://nickm.com/post/2018/08/a-web-reply-to-the-post-web-generation/

NPD Group. “Instapoets Rekindling U.S. Poetry Book Sales.” https://www.npd.com/wps/portal/npd/us/news/press-releases/2018/instapoets-rekindling-u-s—poetry-book-sales—the-npd-group-says/ 2018.

Nacher, Anna. “The Creative Process as a Dance of Agency: Shelley Jackson’s Snow: Performing Literary Texts with Elements,” in Digital Media and Textuality: From Creation to Archiving, ed. Daniela Côrtes Maduro. Bremen. 2017.

Reed, Rob. “Everything You Need to Know About Emoji.” Smashing Magazine. 14 November 2016. https://www.smashingmagazine.com/2016/11/character-sets-encoding-emoji/

Rettberg, Jill Walker. “A Network Analysis of Dissertations About Electronic Literature.” Paper presented at the 2013 Electronic Literature Conference. Paris. http://conference.eliterature.org/sites/default/files/papers/Jill-Walker-Rettberg-A%20Network%20Analysis%20of%20Dissertations%20About%20Electronic%20Literature.pdf

Rettberg, Scott. “Room for So Much World: a Conversation with Shelley Jackson.” EBR. 6 January 2019. https://electronicbookreview.com/essay/room-for-so-much-world-a-conversation-with-shelley-jackson/

Saemmer, Alexandra. “Hyperfiction as a Medium for Drifting Times: A Close Reading of the German Hyperfiction Zeit für die Bombe,” in Analyzing Digital Fictions, eds. Alice Bell, Astrid Ensslin and Hans Rustad. London: Routledge. 2013. Book.

Strickland, Stephanie. “Born Digital.” The Poetry Foundation. 2009. https://www.poetryfoundation.org/articles/69224/born-digital

Cite this article

Berens, Kathi Inman. "E-Lit's #1 Hit: Is Instagram Poetry E-literature?" Electronic Book Review, 7 April 2019, https://doi.org/10.7273/9sz6-nj80