Photo Narratives and Digital Archives; or: The Film Photo Novel Lost and Found

A first draft of this essay was presented at the 2017 ELO Conference at Porto, in a panel organized by the "Nar-Trans" group of the University of Granada.

The “film photo novel“ magazine, a low-brow merger of the film novel and the photo novel that was hugely popular in the late fifties when people liked to read these “films in print“, can be considered today a forgotten genre or medium -not just an unknown or understudied genre or medium, but simply a lost one, to the extent that even specialists of film history and photo narrative may completely ignore its existence.⏴Marginnote gloss1⏴See the ELD glossary entry for Photo-novel, which was inspired by Beatens’ research on the subject.

— Will Luers (Jun 2018) ↩

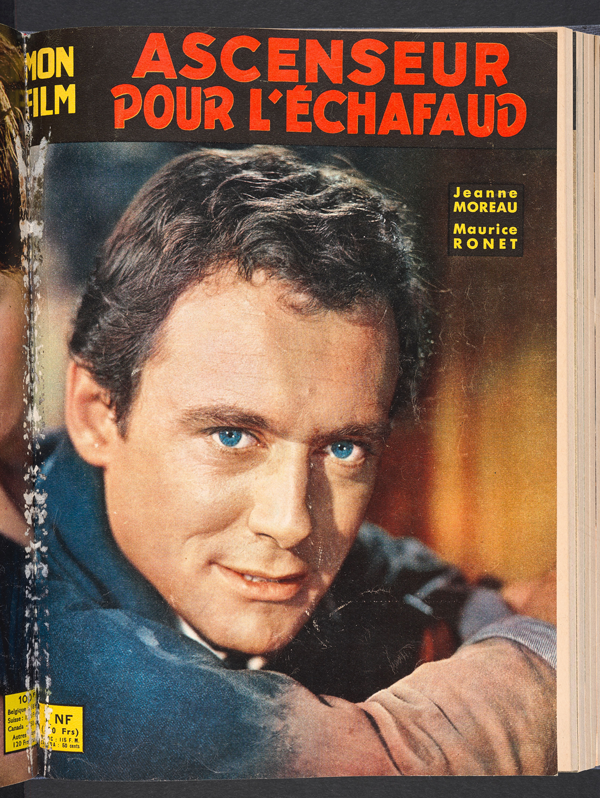

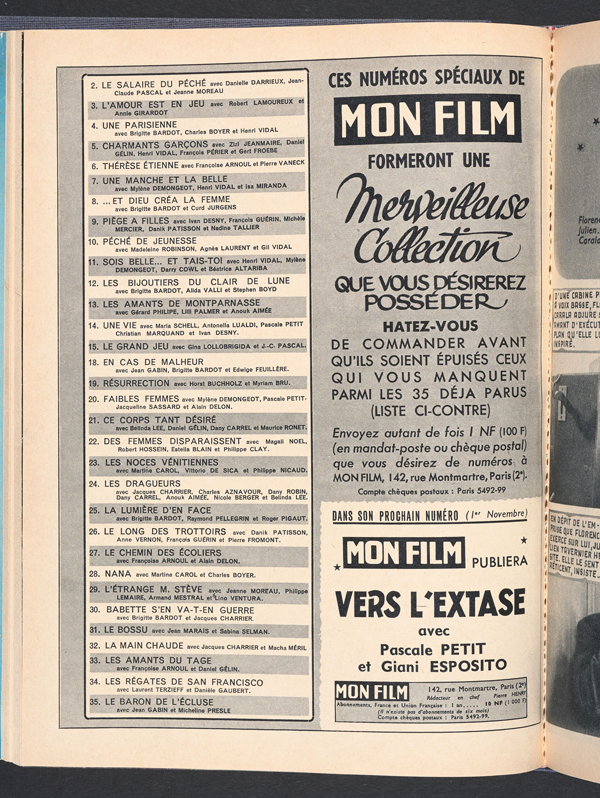

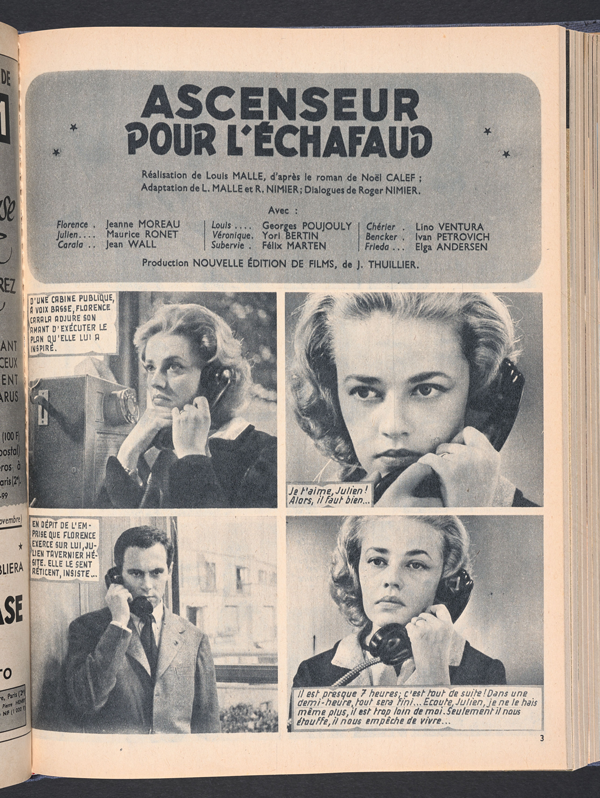

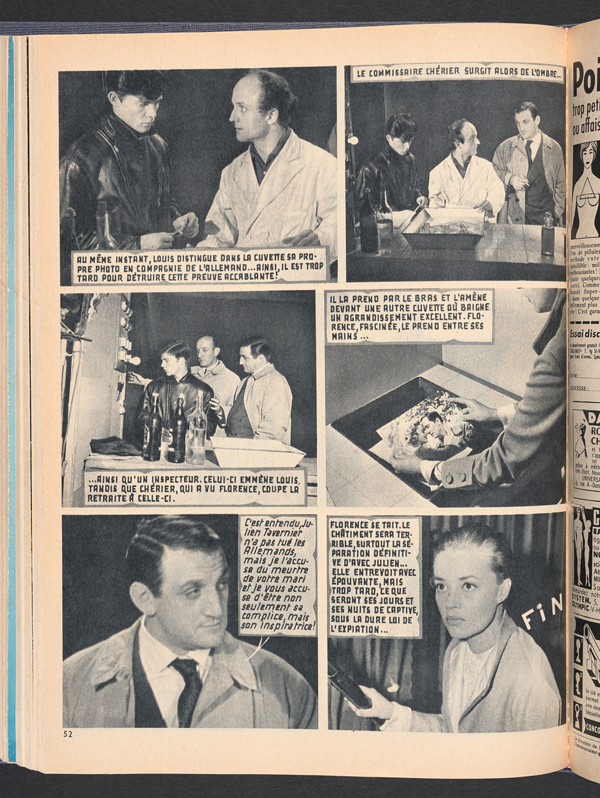

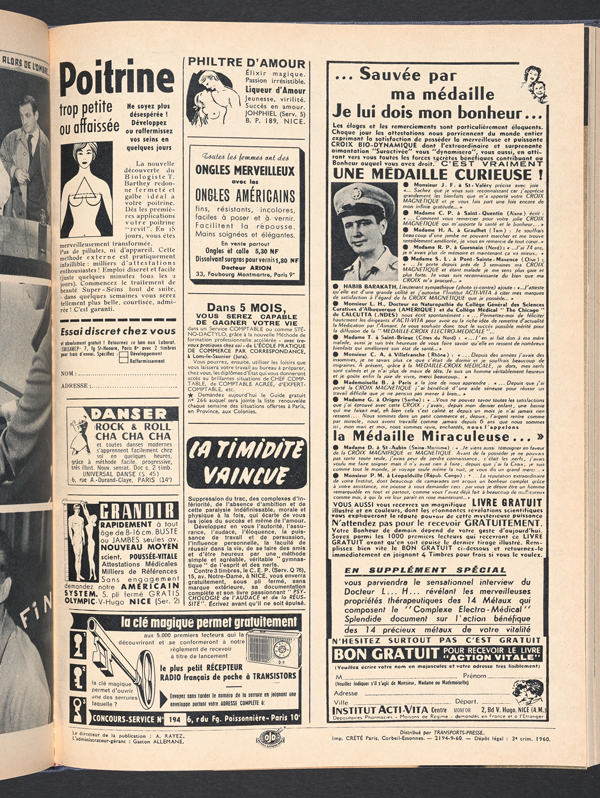

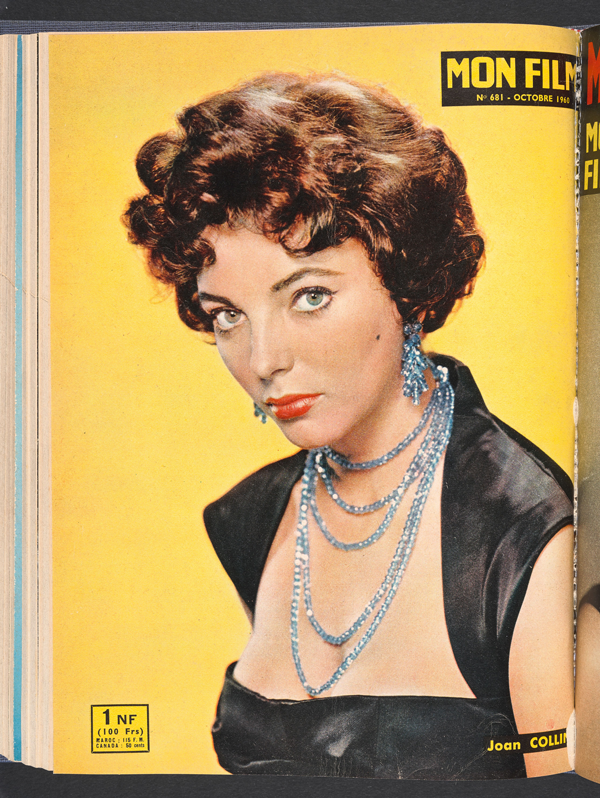

To quote just one example, to give an idea of what these publications actually looked like: Ascenseur pour l’échafaud (“Elevator the Gallows“, also released under the title “Lift to the Scaffold“, 1958), a famous pre-New Wave feature by Louis Malle, well know as well for the jazzy score written and performed by Miles Davis, as republished in Mon Film (n° 681, October 1960), a long-standing French magazine offering “narrated films“. (see six illustrations).

Yet what does it mean to say that a medium is “lost“, beyond the discussion of whether the film photo novel is still present or not in some memories (dinosaurs, after all, no longer exist, but few animals are as well-known as these prehistorical creatures)? To be lost will mean here three things:

- The works themselves are difficult to find, they definitely no longer circulate via their traditional channel, which was the newsstand (or direct sale via subscription).

- In case the works are available, it is not always easy to access their intermedial context. The films that were “adapted“ or “translated“ in these magazines have also become unknown, if they are not lost themselves as well.

- The cultural practices that materialized the medium, namely producing, publishing, circulating, reading, reusing (collecting, swapping, cutting-out, throwing away, etc.) are equally difficult to recover.

In practice, however, the situation is less negative and frustrating, mostly thanks to the impact of digital culture. It is possible to find digital archives and specialized websites on the topic (the best example being Ghéra 2006), although most of them, and perhaps even all of them, belong to the category of what Abigal De Kosnik calls “rogue archives“ (2016). I am quoting from the blurb:

The task of archiving was once entrusted only to museums, libraries, and other institutions that acted as repositories of culture in material form. But with the rise of digital networked media, a multitude of self-designated archivists-fans, pirates, hackers-have become practitioners of cultural preservation on the Internet. These nonprofessional archivists have democratized cultural memory, building freely accessible online archives of whatever content they consider suitable for digital preservation. In Rogue Archives, Abigail De Kosnik examines the practice of archiving in the transition from print to digital media, looking in particular at Internet fan fiction archives.

The material made available on the internet has a strong “conservationist“ dimension -the basic idea being to save as much as possible of what has been lost in predigital culture-, but it often offers much more, such as for instance a strong awareness of the networked character of the film photo novel, which was not a stand-alone medium, but part of a medium network with many ties to a wide range of broader cultural practices (celebrity culture is the first example that comes to mind).

However, it would be a mistake to present these “rogue“ efforts to restore a lost culture in terms of mere “recovery“. This would be the purely “archeological“ aspect of the archive, whereas a rogue archive is also a dramatically performative and productive environment, in which new worlds come into being. Not only because the very construction of this kind of archive is already the creation of something new in itself. But also because in many cases the very existence of the archive is the springboard for new, contemporary creations that update, reinvent, appropriate the lessons of the past (in the example of De Kosnik, the main corpus is feminist comics).

More specifically, the creative and productive aspects of a film photo novel archive -regardless of the new creations that it may inspire- can be described in the same way we initially described the “loss“ of elements:

- The works themselves are transformed in multiple ways. A first change refers to their synecdochical reduction: what we generally find in these archives are less the complete works than bits and pieces (covers, fragments, descriptions, for instance). This fragmentation has great hermeneutical consequences, since the reader or user is almost forced to “invent“ what is not there, if not to “(re)make“ a new version of it… A second change, whose consequences are even stronger, has to do with the spatial rearrangement of the works: the items are no longer presented as internally organized sequences (where all elements are presented one after another, to speak with Lessing), but as lists whose basic organizational principle is now spatial (the elements are presented one next to another -and here the influence of the “poster“ genre so typical of celeb culture cannot be denied). As a result, the visual material of the film novel loses something -the sequential arrangement of images-, but at the same time it also gains something -each picture can become a story in itself, while the visual montage of the various images creates new and sometimes completely unforeseen narratives. Finally, one should not underestimate the “fetishizing“ power of internet culture on paper artefacts: the more works become available on screen, the more we may develop a strong desire for the original paper version -the old story of throwaway pulp items becoming expensive collector items.

- Besides, the rogue archival “salvation“ of the film photo novel liberates these works from their traditional, bi-medial (or bi-modal) structure, and radically changes their status of mere “adaptations“. Rather than being a shallow and superficial translation of the movie, which helps give it a second life once the film is no longer theatrically exploited, the film photo novel as discovered on the internet can be read as a diverse and multilayered universe in itself. Film photo novels are no longer read in relationship with the film they continue -often with variations, in a truly transmedial sense, not simply as adaptations- but in relationship with the series they are part of (each magazine has its own style, and this editorial style is always stronger than the individual style of the single volumes) as well as in relationship with all the other series that were competing for the reader’s attention and money (and since readers could not afford buying too many film photo novels, for they were relatively expensive, the comparative approach of the film photo novel is something that was almost impossible before the creation of modern digital fan culture).

- We may have lost contact with the “historical“ cultural practices of the film photo novel, as demonstrated by the rather disappointing results of the currently available oral history testimonies, but the rediscovery of the film photo novel in internet culture is also creating new communities and new practices, which are no less authentic than the older and “original“ ones.

But what could be a research program for the coming years? The possibilities are immense. So just two examples.

At first sight, it may be tempting to replace the rogue archive approach by a more scientific archival approach. Although it would be absurd to minimize the importance or the necessity of a more structured and traditional approach, as displayed for instance in the curatorial work done by the Italian film museum on its own collection (actually a donation by one filmmaker, Gianni Amelio, who almost singlehandedly created this collection (Morreale 2007); for the French side of the story, see Baetens (forthcoming)), it would also be dangerous to downsize the creative chaos of the rogue archivists. They have managed for instance to maintain a very horizontal and democratic view of the medium, with no “canon“ outlawing 95% of the production -as is happening for instance in the field of the graphic novel, whose roots in underground culture did not prevent it from undergoing very rapidly a strong canonizing dynamics. Moreover, rogue archives also succeed quite well in giving a kind of UFO touch to their objects: film photo novels keep something of their cultural strangeness when presented as free-floating elements in the wide and open sea of fan-based archives, and this openness is key to the possibility of their cultural reframing and appropriation in other contexts, with other means, for other objectives. A productive merger of both systems may be a workable solution, provided each of them can freely develop its own priorities (and it should be stressed that the film photo novel rogue archives are far from having realized all of their potential).

A second, both traditional and radical perspective is the possibility to use the work on the film photo novel as a laboratory for the redefinition of the relationship between text and metatext -and this in the very specific context of a reflection on transmedia culture. The film photo novel is one of the many missing links in the history of what is called the “narrated cinema“, that is the whole range of verbal and nonverbal techniques and practices to “retell“ a film’s narrative (trailers, reviews, novelizations, adaptations, expansions, continuations, etc.). The specific contribution of the film photo novel, as it is being restructured thanks to internet culture, can be twofold: on the one hand, the film photo novel, which often transforms the work in various ways, is a good example to highlight the blurring of boundaries between adaptation (hypertext, in Genette’s 1982 terminology) and commentary (metatext): an adaptation is not only a creative work, it is only a nonfictional act of analyzing the original work (hypotext); on the other hand, this merger of text and metatext also makes room for a more radical repositioning of the metatext, which can become part of the text itself. If the meaning of a work is the sum of the meanings of its interpretations, as it is often said, we should draw the logical conclusions of this remark and include these readings and interpretations in the text itself. The film -photo novel -the metatextual hypertext of a filmic hypotext- is a good example of such a makeover and the conceptual framework of transmedia, which tends to give equal value to all the elements of a media network, can fruitfully encourage this line of thinking.

Riposte to this essay: Riposte to Jan Baetens, Photo Narratives and Digital Archives, or The Film Photo Novel Lost and Found by David S. Roh

Works Quoted

Baetens, Jan (forthcoming). The Film Photo Novel. Austin: Texas University Press.

De Kosnik, Abigail (2016). Rogue Archives. Digital Culture Memory and Fandom Culture. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

Genette, Gérard (1982). Palimpsestes. Paris: Seuil.

Ghéra, Serge (2006). “Ciné-romans“ : http://bmania.pagesperso-orange.fr/Presentoir.htm

Morreale, Emiliano, ed. (2007). Gianni Amelio presenta…Lo schermo di carta. Storia e storie dei cineromanzi.Torino: Il Castoro.

Cite this article

Baetens, Jan. "Photo Narratives and Digital Archives; or: The Film Photo Novel Lost and Found" Electronic Book Review, 30 June 2018, https://doi.org/10.7273/41x5-nb72