Applied Media Theory, Critical Making, and Queering Video Game Controllers

This essay explores intersections among queer theory, critical making methodology and inclusive design through a research creation piece that aims to problematize normative video game controller schemes.

Introduction

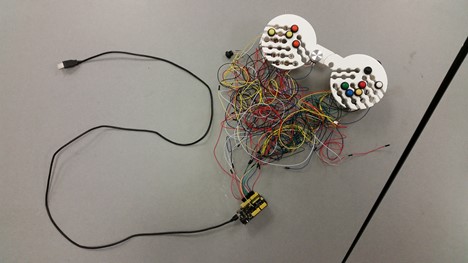

This article explores intersections between queer theory, critical making methodology and inclusive design through a research creation piece that aims to problematize normative video game controller schemes and to question the logic of normative control. Bringing a queer focus to a critical making methodology called Applied Media Theory (AMT), “a method that engages in formal experimentation with media to generate critical discourses and technologies” (O’Gorman, “Broken Tools and Misfit Toys: Adventures in Applied Media Theory”), this article presents the conceptual and methodological basis of an alternative video game controller I made. Built using an Arduino Leonardo microcontroller, toggle switches, arcade buttons and held in a custom-designed 3D-printed frame, the manually and digitally reconfigurable interface of the controller abrades conventional understandings of how a controller should look and function. Its design invites novel engagements with the controller and the ways of playing games with it.

Drawing from queer and disability studies critiques of game controllers as reifications of gendered and able-bodied norms, I discuss how this controller disrupts normative conceptions of able-bodied and masculine forms of power in controller design, including the ways controllers limit and afford subject-positions with video games as gendered and able-bodied players. This alternative controller addresses the ways that queer theory’s focus on destabilizing fixed categories, including norms and identities, can produce functional configurations and engagement with video games that resist normative design logics and complement what Jay Dolmage calls “disability rhetoric”—rhetorical expressions that purposefully and persuasively call attention to the difference of bodies.

The design and function of this research-creation object seeks to queer the ways in which normative conceptualizations of bodies, sexualities, games, and gameplay become naturalized by players’ engagements with apparati of control. This article uses the reconfigurable functions of the controller to think through the implications of alternative control schemes for video game design. In an era of promising developments towards adding accessibility through in-game options, controllers and their accessibility often remain an afterthought—or adapted to fit dominant game designs (see, for instance, Microsoft’s Xbox Adaptive Controller, or the recently announced HORI flex for the Nintendo Switch). This has repercussions that extend beyond how people play into what can be played, for as Stephanie Boluk and Patrick LeMieux argue, changing the controller changes the game. After stressing how controller design impacts dominant game design conventions and the implications of this for queer game designs, this article concludes by describing future directions for research-creation work to engage with queer and inclusive controller designs. To expand queer and inclusive design into mainstream video game design, scholars, designers, and players must engage at the level of controllers.

Queer Critical Making

This controller was made at the Critical Media Lab in downtown Kitchener. Its design process was informed by the mission of the lab itself: to critically engage with technoculture, often through the making of research creation pieces that combine media theory and making technology in critical ways. The construction of this controller followed a methodology formulated by Marcel O’Gorman at the University of Waterloo’s Critical Media Lab (CML), a transdisciplinary research space that blends critical theory with interrogations of technoculture. In Necromedia, O’Gorman articulates what he calls an Applied Media Theory (AMT), a methodology for critical theory through critical making. With AMT, research and theory inform the design and creation of critical objects, with each step in this process of critical making affording ways to theorise about media and technology (143–48). In Making Media Theory O’Gorman stresses the importance of this methodology, arguing that makerly objects can “serve as vehicles for media theory” (5).

I designed and built this controller using a Leonardo microcontroller and a 3D-printed frame. As anyone can tell just by looking at it, it’s different, maybe even a little janky, though at first glance it might look like just a knock-off game controller. But in fact, this object is not like the other controllers—this one transforms. There are several rows, each with six rounded holes, which allow the user to replace the buttons in any configuration they want along this grid. The grid is also repeated along the shoulders of the controller, so players can even place all the buttons along the top. The object also splits apart, so the hands do not need to be brought together to play. Because it is a microcontroller, the button configuration can be remapped at the coding level, allowing any button to input any key. Put another way, each player can adapt the controller to their own needs.

The design and functions of the controller abrade conventional understandings of how a controller should look and function, and invites novel ways of engaging with the controller and of playing games with it. When you first encounter it, the controller does not behave the way we would expect it to. The elements of the controller confound easy explanation, and can also add unpredictability to the act of playing (especially if you do not know which button performs which command). Its exposed tangle of circuitry and reconfigurable inputs attempts to make manifest the radical indecipherability at the heart of queer theory. In this way, it serves as a queer rhetorical object that provokes new understanding of controllers and how they influence game design. Indeed, as Bonnie Ruberg points out, “Queerness and video games share a common ethos: the longing to imagine alternative ways of being and to make space within structures of power for resistance through play” (1). Bringing this queer perspective in line with Jay Dolmage’s call for “disability rhetorics” as a way to bring difference into spaces that otherwise excluded it (Dolmage), I am aiming for a more inclusive framework through which we might think about and instantiate difference in gaming technologies, both physical and digital.

The background for this piece does not have one direct theoretical throughline. I first started thinking about making a controller after my experiences in a Media Archaeology course, co-taught by Drs. Darren Wershler, Lori Emerson and Jussi Parikka at the University of Concordia in 2017. The capstone project was to hack an Ikea table into a retro-pi arcade cabinet. It was my first time emulating a console, and during the installation phase we needed to test each of the buttons, so Dr. Lai-Tze Fan scooped them all up and held them like a bouquet. And I was intrigued by this jumble of inputs, held together in no discernible order. What appealed to me most about this jumble was the twisting and bending of wires, and the way the interacted with the hands trying to make each input register with the emulator. And I thought it was a perfect representation of the twisting, bending difference at the heart of queer theory articulated by queer scholars like Sara Ahmed and David Halperin. Between Ahmed, who describes queer as a kind of twisting and bending (Ahmed), and Halperin, who describes queer as a way of abrading and rubbing against the grain (Halperin), the jumble reminded me how ways of being queer in the world abrade because they deviate from the normative. Maureen Engel, a media theorist and queer game designer, observes that “queerness stands as a disruptive challenge to normative structures, be they identities, institutions, cultural productions, or ways of being in the world” (Engel 352). The rules of heteronormativity are made apparent when the matrix of one’s being is configured differently than the norm—towards the “wrong” way, leading to deviations from the normal orientation, away from the matrix of normativity. And I was struck by the way that the disruptive challenge afforded by the bouquet went away when we fixed it into the table. And I wondered if there might be some way to sustain this fluidity. In other words, I wanted to use queer theory and critical making to literalize queer dynamics (the relations between people, places, things).

As this jumble of theorists might suggest, there are several media theoretical strands that informed my controller design. Adding to this mix is Rita Raley’s theory of tactical media. Raley’s critique focuses on the instances of “disturbance” (6), whereby research creation, in tracing the flows of power through a system, draw attention to critical sites where intervention may be possible, to use media theory “to express dissent and conceive of revolutionary transformation” (1). To my mind, Raley’s emphasis on disturbance anticipates M.D. Schmalzer’s concept of jank.1 Schmalzer refers to jank “as a catchall phrase for a certain kind of weirdness that … disconnects between player expectations about how elements of videogames (software, hardware, interface, rules, mechanics, visuals, etc.) ‘should’ behave and how they actually do” (Schmalzer). By disrupting the direct correlation between input and output, both tactical media and jank offer a means to understand how the design and deployment of technologies and their interruptions structure the very language of any subsequent critique.

How might critical making as ‘tactical jank’ disturb and jank immersion without perpetuating the hegemonic designs these critical theories are intended to resist? My aim with this critical controller is to embody a theory of tactical media technologies I have described elsewhere that articulates how power is framed and reproduced in the first place (Lajoie). Whether it achieves a truly radical disruption, or merely represents an instance of dissent with modification is beyond the scope of this essay, and indeed my concern. The controller functions as a rhetorical object for persuasive ends that I will describe below. It serves as an evocative offshoot of possibility, perhaps even a provocative prototype—a provotype, or proposal intended to provoke (Smolicki). And as a prototype, it is purposefully incomplete, and must remain so; as a queer object I want it to remain already on the edge of becoming something else, to adapt according to user needs.

My research-creation object is intended as a queer rhetorical object that attempts to queer the design of controllers and thereby provoke new meanings about what controllers can be and how they influence game design. I made this controller to queer the functionality of a Super Nintendo controller (the controller I grew up playing—and which informed my game control literacies), so there are twelve keys, (up, down, left, right, a, b, x, y, left shoulder trigger, right shoulder trigger, select and start), but each key is represented by four different kinds of inputs on the controller (so, 48 total buttons): a classic button input, and three types of switches: on/off, on/on and momentary on/on. The functionality of the toggles also contribute to queering the logic of control: though they might all look the same, there are in fact three different kinds of toggles, offering two types of mechanical interaction—momentary and set. Some will spring back, others will stay put. What this means in practice is that some toggles might stay on, while others will offer a momentary press. Playing a game that requires you to hold down one button to run and a press a second button to jump? Assign the running button to a set toggle and speed run through a level.

The visual language of the controller aims to challenge the traditional design logic of game controllers playfully yet seriously. For instance, whereas the chassis of video game controllers are enclosed for the durability of the controller this also makes them difficult to alter or even repair. (Having recently tried to repair the left trigger on a PS4 dualshock remote, I am conspicuously aware of the fragile and interlocking nature of the various parts that comprise a modern-day controller.) The chassis of this controller offers a matrix that invites people to adapt the controller to suite their needs. Though this controller engages with the design logic and idioms of the Super Nintendo controller to invite players to play the games from that system, but on their own terms.

There is obviously room to improve the controller in terms of its accessibility. The design is deliberately disorienting in a way that can create an unnecessary barrier to access. It is manually difficult to reconfigure the inputs. The buttons pop in and out easily enough, but the toggles require fiddling with tiny nuts and bolts. The buttons are probably too small, the toggle switches can present a challenge to activate, my wire management is atrocious, and the layout of the controller, designed to fit the contours of my hands, can be ungainly for others to hold.

Aside from the physical placement of the buttons on the chassis, the buttons can be changed at the level of code, and even the object file itself can be altered. Indeed, users are invited to adapt the layout to their own needs at multiple levels of design—going in and changing the object files and reprinting it as needed, or remapping the buttons in the interface.2

Controller as site of critique

Jess Marcotte argues that since controllers “provide a player with a sense of control and agency” they offer sites of disruptive potential (Marcotte). According to Marcotte, queering the controller offers a means heteronormativity. There are several examples to draw from in the realm of inclusive, queer, and alternative controller designs. Dietrich Squinkifer and Jess Marcotte have made controllers involving paper plate gongs, crocheted yarn objects and even live plants. Of Marcotte’s other work with alternative, hybrid and queer controls, one was a collaboration with Squinkifer involving a live plant. In “RUSTLE YOUR LEAVES TO ME SOFTLY”, players engage with a plant, which responds by “playing soothing sounds and plant-related words and poetry”. For more examples, see Enric Llagostera’s online repository, the Shake that Button archive, as well as the webpages of alt.ctrl.GDC, an event which takes place every year at the Games Developer Conference Expo. What each of these alternative controllers emphasize to me is the ways that controllers are integral in determining game design, and how important they are to consider in game studies.

Much of our interaction with any video game is mediated at the level of the controller, which functions as a prosthetic extension of the player into the game world. Kat Holmes, who worked for 9 years as an inclusive designer at Microsoft, and now works at Google, calls controllers “gateways to vast virtual worlds” with the keys held by designers (42). As she puts it, “the people who make solutions hold a power to determine who is and who isn’t able to participate” (44). As both entrance and barrier, controllers become an object of cruel attachment for players with disabilities. This idea of cruel attachment is my attempt to repurpose what queer theorist Laura Berlant calls queer optimism, “a double-bind in which your attachment to an object sustains you in life at the same time as that object is actually a threat to your flourishing” (Seitz). Indeed, John R. Porter, an inclusive designer at Microsoft, describes some of the makeshift controller hacks he and his family made when he was a kid, including Playstation controllers with little pieces of wood taped to the buttons, and how discouraged he felt to try playing the game because the controller was blocking him from accessing the game. Porter explains that the controllers often make it difficult, and sometimes impossible to interact with the worlds because the technology “was made without ever even considering the possibility that someone would need to interact with it in the ways that I do. That places the onus on me to figure out all these workarounds. For gamers with disabilities, we have to spend as much time figuring out how to play a game as we do actually playing” (qtd in Holmes 46).

Today, mainstream companies are increasingly conscientious of the need for inclusion solutions. Consider Microsoft’s adaptive controller, which is intended as an accessible controller for the ne. The pieces come separately or as a kit, and replicating the functionality of an controller, and the costs can be exorbitant. Securing the full collection of controllers is expensive—about $0 worth of materials, not including the or the game or any other factors. The is also only available on the Microsoft tore. This niche marketing approach remains a persistent trend that stretches back to the beginning of alternative controllers. In 1989 Nintendo produced a hands-free controller for their Nintendo Entertainment System (NES), which it sold exclusively through a consumer hotline for approx. $170 USD (IGN). Like Microsoft selling the controller only through its webstore, these sales approaches compartmentalize assistive controllers as niche products for disabled players only, who are expected to adapt to conform to normative standards of the game industry. To play with these controllers is to do so on normative and ableist terms, where everyone else is a niche aftermarket if they are thought of at all. It also tethers accessibility to corporate enthusiasm, and leaves consumers at the mercy of companies to continue to support the tech.

Offering these controllers as niche products essentially brackets disability within normativity, in a way that tells players they can play, but on terms, games designed with able-bodiedness in mind—if they can find the right controllers, and if they can afford them. To be clear, I am not trying to disparage the work that companies have put into making these controllers. What I am critiquing is a system that places normative bodies at the centre of design—both controllers and the games that are made with them in mind. A system that contributes to what Fron et al. declare a “hegemony of play” (309): “an entrenched status quo” that perpetuates, as Ruberg explains, “assumptions about what video games should be like, who should be represented in games, and what types of players count as ‘gamers’” (4). The problem is not that a company like Microsoft charges premium prices for a premium product, the greater issue is that no alternatives exist for the Xbox, and few other alternatives exist for other consoles.

The marginal status of these controllers also informs when their functionality is considered in a game’s design cycle. While inclusive, these designs nonetheless take the mainstream control scheme as a fundamental design logic, ensuring everyone can play the same game on the terms set by able-bodied play. Rather than asking how different identities might change the design of the game, these accessible designs seek to make the game accessible to all, and as is often the case, the hegemony of able-bodied play dominates. In this sense of making design accessible, I am invoking the paradigm of inclusive design articulated by designer Graham Pullin, which is design that “seeks to make mainstream design accessible to everyone” (2). Universal design, as it is more commonly known in North America,3 has been described as one-size-fits-all solution that ignores that range of identities engaging with that design (see Holmes 104).

The marginal status of these controllers perpetuates able-bodiedness as the primary design logic and control idioms of video games. Game designer Anna Anthropy notes the effect of this repetition:

After over thirty years of catering to an audience that is continuously playing and learning games—an audience that hence requires more and more complicated games to interest it—games and the controllers with which players interact with them have become more and more complex. This is not to say different: layers of complexity have simply been added to the same few models of games and the same few models of controllers. (ch.1)

This continuity extends to the design of controllers as well—Anthropy helpfully points out that even a Microsoft Xbox controller perpetuates the design logic of a controller from thirty years before. “The means players use to interact with games guides the design of those games” and determines what games are accessible to which players (ch.1). The skills required to play games within this dominant literacy also depend on sustained engagement with video games that reinforces their exclusively. As Schmalzer points out, “[l]iteracies are also promoted from title to title through the consistent mapping of actions to certain inputs” (Schmalzer) Players are expected to adapt to the culture and adopt its literacies, or else struggle to play until they ‘git gud’ or give up.

We need more controllers that work against the emphasis placed on ability orthodoxy in game culture—and more games that follow from these queer and alternative controllers, rather than the other way around. My aim with this controller to queer both how a controller should function, and thereby queer what it means to control games. Research-creation thus serves a persuasive means to engage with queer design to further blur these boundaries between designing for and with difference. The reconfigurability of the controller scheme serves a dual rhetorical purpose in that it both concretizes the metaphorical undecidability of queerness and abrades normative understanding of how a controller should look and function. For instance, we could also imagine new ways of altering the game to slow down or even speed up certain events to afford greater accessibility for all players, and mapping these affordances to buttons.

As Stephanie Boluk and Patrick Lemieux point out in Metagaming: “Whereas standardized controls standardizes play and produces normative players, alternative interfaces do not simply make videogames accessible, [they] radically transform what videogames are and what they can do” (36). Marcotte similarly notes that “By queering game controls and controllers, we can access more ways to question, transform, resist, imagine, and bring difference to game design more broadly” (Marcotte).

What these critiques are also getting at are the ways that access to games remain regulated by the capacity to engage with the controller, which has been historically privileged around having the right number of hands and fingers as well as privileging the ability to operate the requisite number of same to access the levels, experiences, interactions promised by games. As Sheila Murphy explains in The Routledge Companion To Video Game Studies, “Whether paddles, joysticks, buttons, analog sticks, steering wheels, track balls, keypads, light guns, or other objects, game controllers fundamentally structure the gamer’s experience of hardware and software” (19). In “Queer(ing) Gaming Technologies: Thinking on Constructions of Normativity Inscribed in Digital Gaming Hardware,” Gregory Bagnall points out the problematic design aesthetics of these controllers as “gaming technologies … inscribed with heteronormative constructions of difference” (135). ontrollers ask us to think about our positionality and identity. My aim with the alternative controller was therefore to destabilize the fixed structure of the controller, to open up possibilities to resituate the controller as a locus of control, and mobilize alternative possibilities for control. This controller aims to evoke and thereby interrogate these affordances and constraints. Put another way, it aims to queer not only the bodies that interact with controllers but the identities too.

While the controller surfaces these tensions, its current design stops short of addressing them—in part because I am not aiming to create an inclusive controller design. Instead, I am aiming to critique the design logic that perpetuates normativity and able-bodiedness a the centre of games culture, which in turn controls the kinds of games, play experiences, and cultures that emerge. I am calling for a queer approach to identity-based design, where the messy and often irresolvable complexities of being different expand rather than universalize design. Part of my intent in doing so is to imagine what a queerer, more inclusive alternative future could look like, where these sorts of controllers are at the epicentre of video game infrastructures, not marginal accessories.

As has been often stated, video games are for everyone. Every person should be able to play the video games they want, and in ways that supersede cruel attachment. The more people we include in the design process, the greater the accessibility. This affords opportunities to create alternative controls that afford new possibilities of play. Though idiosyncratic and highly theoretical, this object engages with tactical jank and queer critical making to provoke players to think about navigating in game worlds and the real world in ways that afford being queer and inclusive, and without trying to fix, bracket, or negate these differences. The controller encourages users to play and adapt its design, to overcome the mismatches between their identity and the ways they are expected to navigate both the real world and game worlds. As a research creation piece and as a controller, it is intended to provoke us as players, designers, and individuals to make our own ways of moving, feeling and knowing worlds, and making our differences matter—in every sense of that word.

Project arduino code: https://github.com/ludicscribbler/queer-controller/tree/main

Project object file: https://www.tinkercad.com/things/2ZjK0IVf8nZ

Notes

- Perhaps contributing to this connection is that one of Raley’s sites of tactical media is a “persuasive game” (an idea formulated by Ian Bogost in Persuasive Games).↩︎

- I make this suggestion cautious of the other barriers this involves, namely, the technical skills required to redesign and print the controller, to resolder the inputs, and the coding skills needed to remap the buttons. There are also additional barriers to accessing the necessary technologies like computers, 3-D printers, soldering irons. There are so many barriers to overcome, but all which can be overcome. Indeed, the requisite skills can be taught, and in a single workshop no less. Nonetheless, these barriers point to the kinds of structural inadequacies that threaten the inclusive possibilities of game systems.↩︎

- There is no consensus on this nomenclature. Pullin claims Universal Design in the United States is known as Inclusive Design in Japan, whereas Kat Holmes prefers to differentiate inclusive design as being closely related to universal design (see Holmes 55).↩︎

Works Cited

Ahmed, Sara. Queer Phenomenology : Orientations, Objects, Others. Duke University Press, 2006.

Anthropy, Anna. Rise of the Videogame Zinesters: How Freaks, Normals, Amateurs, Artists, Dreamers, Drop-Outs, Queers, Housewives, and People Like You Are Taking Back an Art Form. Seven Stories Press, 2012.

Bagnall, Gregory. “Queer(Ing) Gaming Technologies: Thinking on Constructions of Normativity Inscribed in Digital Gaming Hardware.” Queer Game Studies, edited by Adrienne Shaw and Bonnie Ruberg, University of Minnesota Press, 2017, pp. 135–45.

Boluk, Stephanie, and Patrick Lemieux. Metagaming: Playing, Competing, Spectating, Cheating, Trading, Making, and Breaking Videogames. University of Minnesota Press, 2017.

Dolmage, Jay. “Disability Rhetorics.” The Cambridge Companion to Literature and Disability, edited by Clare Barker and Stuart Murray, Cambridge University Press, 2017, pp. 212–26. Cambridge University Press, doi:10.1017/9781316104316.016.

Engel, Maureen. “Perverting Play: Theorizing a Queer Game Mechanic.” Television & New Media, vol. 18, no. 4, May 2017, pp. 351–60. SAGE Journals, doi:10.1177/1527476416669234.

Fron, Janine, et al. “The Hegemony of Play.” Proceedings of DiGRA 2007 Conference, pp. 309–18.

Halperin, David. Saint Foucault: Towards a Gay Hagiography. OUP USA, 1997.

Holmes, Kat. Mismatch: How Inclusion Shapes Design. MIT Press, 2018.

Lajoie, Jason. “Critically Unmaking a Culture of Masculinity.” Enculturation: A Journal of Rhetoric, Writing, and Culture, no. 29, Nov. 2019.

Marcotte, Jess. “Queering Control(Lers) Through Reflective Game Design Practices.” Game Studies, vol. 18, no. 3, Dec. 2018. Game Studies, http://gamestudies.org/1803/articles/marcotte.

Murphy, Sheila. “Controllers.” Routledge Companion to Video Game Studies, Routledge, 2013, pp. 19–24.

O’Gorman, Marcel. “Broken Tools and Misfit Toys: Adventures in Applied Media Theory.” Canadian Journal of Communication, vol. 37, no. 1, 2012, pp. 27–42, doi:10.22230/cjc.2012v37n1a2519.

O’Gorman, Marcel. Making Media Theory: Thinking Critically with Technology. Bloomsbury Publishing USA, 2020.

O’Gorman, Marcel. Necromedia. University of Minnesota Press, 2015.

Pullin, Graham. Design Meets Disability. MIT Press, 2009.

Raley, Rita. Tactical Media. University of Minnesota Press, 2009.

Ruberg, Bonnie. Video Games Have Always Been Queer. NYU Press, 2019.

Schmalzer, M. D. “Janky Controls and Embodied Play: Disrupting the Cybernetic Gameplay Circuit.”Game Studies, vol. 20, no. 3, Sept. 2020. Game Studies, http://gamestudies.org/2003/articles/schmalzer.

Seitz, David. “On Citizenship And Optimism: Lauren Berlant, Interviewed by David Seitz.” Society + Space, 23 Mar. 2013, https://www.societyandspace.org/articles/on-citizenship-and-optimism.

Cite this article

Lajoie, Jason. "Applied Media Theory, Critical Making, and Queering Video Game Controllers" Electronic Book Review, 12 September 2021, https://doi.org/10.7273/akvg-xm09