Anna Nacher explores the emergence and spread of the viral hashtag "Kralovec," a satirical Czech language meme protesting the Russian annexation of Ukrainian territory in September 2022. In discussing the social and political impact of memes as collaborative sites of making meaning through media, Nacher analyzes the "creative frenzy" that emerges when protest becomes memetic.

In the very last days of September, just when I was working to set up a meeting with Rob Wittig, Joellyn Rock, Mark Marino and Cathy Podeszwa, who are core members of the foundational netprov team, I had a chance to watch in awe how a spontaneous Twitter phenomenon had come into existence and then rapidly unfolded over the course of days, if not hours. At some point—and probably because my mind was already firmly set on all things netprov—it dawned on me that what is emerging before my eyes is precisely the prominent case of a “collaborative fiction-making in available media” (Wittig 1), although completely unscripted.

The whole thing started around the time when Vladimir Putin announced the annexation of four Ukrainian districts of Zaporozhe, Kherson, Lugansk, and Donieck, following alleged results of sham referendums carried out in the area between 23 and 27 September, when according to occupiers 93.7% of voters favored becoming part of Russia (or, as occupiers framed it, “reunification with Russia”). The whole procedure, run with outrageous violation of basic democratic rights and in the context of widespread war crimes committed by the Russian Army in Ukraine, caused a global uproar. On 26 September, @SniperFella announced on Twitter that Russia has been annexed by NAFO and starting on that day it will change its name to NewFellaLand. The tweet has resonated across the world. It has generated 4000 retweets and more than 24 thousand reactions. NAFO (@OfficialNAFO) is itself an interesting phenomenon. The acronym stands for the North Atlantic Fella Organization (an obvious ironic shot at NATO, North Atlantic Treaty Organization) and is a spontaneous movement consisting of internet activists, politicians, journalists, and ordinary users who joined forces to counter the Kremlin disinformation and to raise funds to support those who defend Ukraine in the military theatre. It was apparently started by a young Pole, @KamaKamilia, in May 2022, who at the time was raising funds to support the Georgian National Legion in Ukraine (Scott). However, the group's weapon of choice is the ubiquitous “doge,” or Shiba Inu—badly represented, sometimes bordering on the aesthetics and ontologies of dank memes. Activists call themselves “fellas” (just like @SniperFella who proposed NewFellaLand) and specialize in viral content aimed at combating Kremlin war propaganda, including videos of the Russian army set to music, intently mocking the efforts of occupiers. Along with @SaintJavelin (a fundraising movement established in February 2022 by Chris Borys, a journalist with ties to Poland and Ukraine) they constitute a swarm of digital activists supporting the Ukrainian efforts at keeping occupiers at bay. Merchandise also includes customized Twitter “doge” avatars for those who donated to support the Ukrainian Army, in which case @fellarequests is tagged and that’s how the movement of “NAFO fellas” is growing, also signaled by #WeAreNAFO. As of October 20, there are statistics that 5000 tweets a day link to NAFO content. A significant chunk of those tweets is constituted by interactions with Russian politicians (such as the case of Mikhail Ulyanov, a Russian diplomat, who after a discussion with one of the “fellas” eventually was chased out of Twitter).

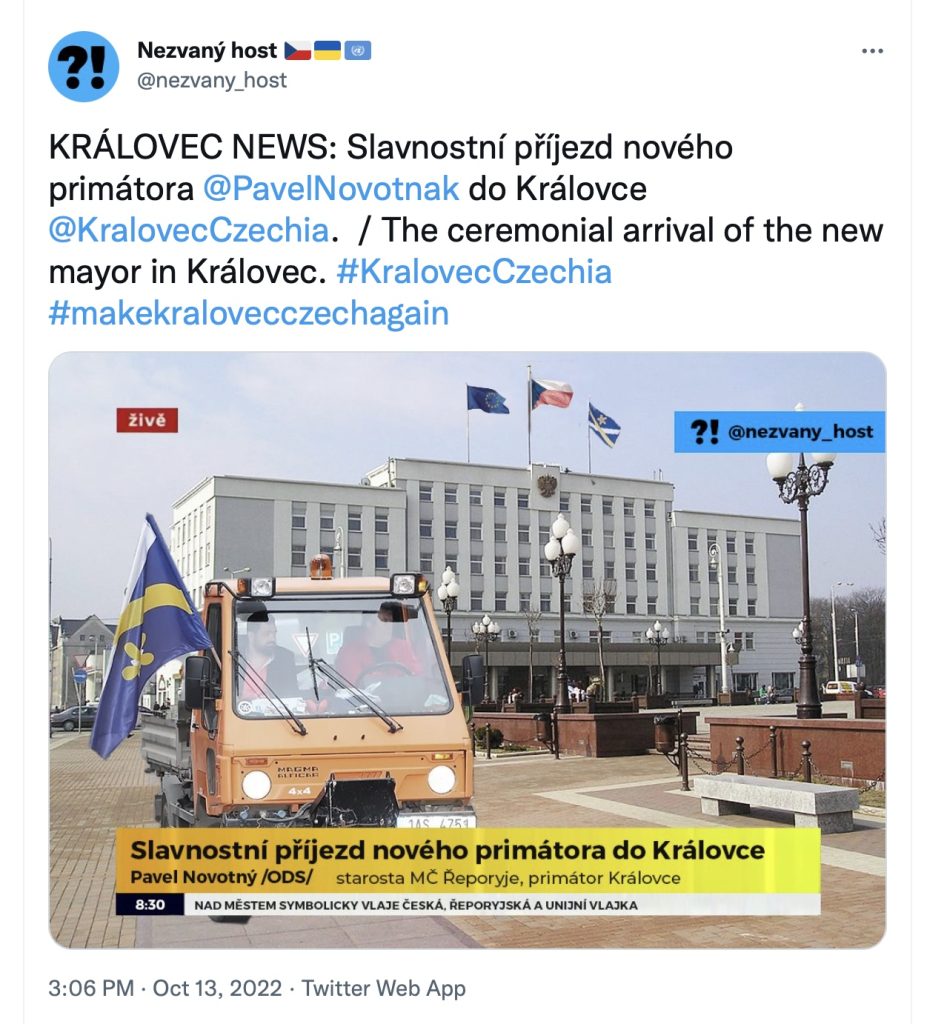

So it is within such a broad context that a spontaneous, meme-centered, anti-occupation Twitter phenomenon was kickstarted on September 28th with just one tweet (and then a couple followed, and then a narrative already started interweaving). A Polish Twitter user known as @mihaszek or papież internetu (the pope of the internet, which in Poland bears strongly ironic meanings) mockingly proposed: “Time to divide Kaliningrad, so that our Czech brothers finally have access to the sea” (“Czas podzielić Kaliningrad tak, aby nasi bracia Czesi mieli w końcu dostęp do morza”). The tweet was immediately reposted by a Czech Eurodeputy, Tomáš Zdechovský with the comment “How not to love Poles.” In a comment on Russian media’s serious and offended reaction to this prank, Zdechovský remarked that Kaliningrad was establish to honour Czech king, Otakar II. What ensued over the next days, grew into a networked political fiction-making performance on a mass scale, including thousands of ordinary users, but also politicians and even institutions such as the Czech Railways or the Prague metro. An avalanche of spontaneously generated content with highly viral potential flooded Czech and Polish Twitter within just hours, most of which is documented on the official Twitter account, @KralovecCzechia. A mock-up website of the new entity, #VisitKralovec (https://visitkralovec.cz was also created, although most of the links are inactive as of October 28th)—Kralovec as a Czech version of the name of the city currently known as Kaliningrad, in Polish sometimes refer to as Królewiec. On October 4th, @KralovecCzechia announced that in a successful referendum 97.9% of inhabitants supported annexation by Czechia, hence Kaliningrad will be renamed Kralovec and merged with Czechia. Similarly to NAFO, an initiative under the name “Make Kralovec Czech Again” was set up on October 4th, with the goal of selling thematic merchandise to support Ukrainian military (https://www.zbraneproukrajinu.cz/kampane/make-kralovec-czech-again ) (as of October 30th, 689 people contributed, raising 673,263 Czech crowns, equivalent to 27,500 EUR). The initiative was associated with an already existing campaign known as Dárek pro Putina (@DarPutinovi , or 'a gift for Putin').

However, what is particularly interesting is how quickly such spontaneous actions are getting transformed into a distributed narrative (Rettberg) via the whole network of associated profiles. Such a distributive narrative is often crafted with a specific hashtag which unites bits and pieces of fragmented, multifarious and incoherent storylines. In this case it is simply #Kralovec, #MakeKaliningradCzechiaAgain, #MakeKralovecCzechiaAgain, or #KralovecisCzechia. We are reminded by Elisabeth Losh that the hash symbol tells the computer that a particular word or words should be read as more important than other words in a given message for purposes of sorting digital content into similar clusters

(Losh loc. 121), which emphasizes the ability of hashtag to make a particular message travel

(Losh loc. 156). Elsewhere, I analyze the narrative potential of hashtag in feminist digital activism contributing to and reinforcing the message of massive street protests against further restrictions on women's reproduction rights that erupted in Poland in 2016. Such potential mobilizes the high level of transversality, instigated by a message traveling across communication networks, computing devices, as it is stitching together

different stories of feminist resistance making them continue this travel (Nacher). In the case of #Kralovec, the hashtag immediately acquired traction with the whole set of related profiles, some of which tackled prominent and well-known popcultural references. For example, Namořnictwo ČR (Marine Regiment of Czech Republic) (@BaltTweetuje) tweeted “Vytyčujeme novou státní hranici.” illustrated with a caption from Czechoslovak cartoon character, Krteček, widely known throughout the former Soviet bloc and often associated with cultural nostalgia, but also serving as an emblem for transnational popular culture in post-communist countries. A similar profile, Vojenská a Namořská Akademie Královec (Military and Marine Academy of Kralovec) (@MyJsmeKralovec), self-identified as “directly administered by Ministry of Defense,” announced on October 5th that it plans to recruit its cohorts in cooperation with the Czech Army (@Armada CR). That is an example of another prominent feature of the rapidly evolving movement: its constant blurring of the borderline between fiction and reality. The impression was ever strengthened by real actors participating in the political fiction. For example, Česke Dráhy (Czech Railways) announced on its Twitter profile the launch of the new direct connection to Kralovec, with a comment that now finally the travel will be quicker and more convenient. The Prague metro profile tweeted about the plan to extend the Czech capital city transit system with a line to Kralovec. Some politicians quickly jumped on a bandwagon, for example, Polish prime minister, Mateusz Morawiecki, who referred to Kralovec in a meeting with a Finnish PM, and a Slovak president, Zuzanna Čaputová tweeted that she may or may not visit Kralovec, but she wishes the new territory all the best.

Apart from real-life institutions tweeting about political fiction of Czech #Kralovec, fictional Twitter profiles mushroomed that mimicked typical urban institutions and organizations, like Královecká Filharmonie and Kralovec Philharmony (@KralovecPhil). According to the basic information provided in the profile, it is located at the address of J. Cimrman Square, Nam. J. Cimrmana, in Kralovec, Czech Republic. The choice of the patron is strikingly brilliant considering the circumstances: Jara Cimrman (aka Jára da Cimrman or Jaroslav Cimrman) is a fictional character invented in 1966 by Ladislav Smoljak, Jiří Šebànek, and Zdeněk Svěrák as a protagonist of a radioplay Nealkoholická vinárna U Pavouka (Non-alcoholic Wine Bar At Spider). His figure was presented as one of the most distinct Czech geniuses, a man of many talents and successes: a playwright, composer, poet, traveler, and inventor. According to the North American Cimrman Society, he was “born to Marlén and Leopold Cimrman on a freezing February night in 1857, 1864, or 1876”. (The Headquarters of the North American Cimrman Society). It should not come as a surprise that he is the real father of the internet (Peterka). On 6 October, Czech news TV, T24, broke the news (delivered by none other than Zdenek Sverák) that the second family home of Jara Cimrman has been discovered in Kralovec and that, in fact, his alias there was Immanuel Kant. On the same day, one of the TT users announced that Kralovec is the first in the Czech Republic to legalize same-sex marriage. Then there is also KralovecAir, @Air Kralovec, whose goal is to provide a safe connection between main Czech cities: Prague, Ostrava, and Kralovec. The Czech Ministry of Defense has its chapter in Kralovec, operating under the handle of @ObranaKralovec. The book lovers can find a regional library, Krajská Knihovná Kralovec, under @knihykralovec. Of course, Slovak people are also present, as SlovacivKralovci, or @SlovaciV, as is Obchodni Centrum Královec, the first mall in Kralovec (@OCKralovec). Footbal fans can follow TJ Sokol Kralovec (@KralovecTj). The Russian Embassy could not be missed, so @EmbassyKralovec threatens: “We strongly condemn the annexation of Kaliningrad by the Czech Republic. You will be sorry for this! Also, cancel cancel culture!” In another tweet the Embassy informs that—in face of Israel rejecting the plea to deliver weapons to Ukraine—Israel is Russia’s closest ally, “right after Elon.” Elon Musk’s now infamous tweet where he proposed that Ukraine cedes some of its territory as a way to end the war is praised for the content of a “faithful servant.” As of October 31st, #Kralovec was apparently still alive—a Haloween-themed tweet was posted, with Trump and Putin stylized after a famous Diane Arbus’ Twin photo and warning in Czech: “if you see these two girls at your door, do not open under any circumstances and do not give them any treats.”

What I provided here is just a tiny fraction of a collaborative work of imagination and creative frenzy that was also a way to vent off a sense of constant threat, continued news of Russian war crimes, massacres and assault on civilians that Central and Eastern Europe has been living with since February 24th. It could be probably considered (and most often is) a weaponized meme culture, or—as is also quite reasonable under circumstances—a form of community therapy and relief. Although we all know the darker face of the platformized Internet, and what I am describing here had been happening on Twitter before Elon Musk took it over, it seems that at times, indeed, “[m]emes are the street art of the social web, and, like street art, they are varied, expressive and complex” and that sometimes “memes help make transformative and positive changes in society” (Mina 12). While I am tempted to emphasize that a meme power may lie in its transversal, highly mobile potential, the fact is that this power is not always used in noble ways. It can, however, serve both as a tool that may help to cross boundaries, divisions, and aesthetics and a way to further drag us into dependency on a particular platform—in this case, Twitter (but it could also be Facebook, Reddit or any other corporate entity organizing the spaces of communication and exchange of the contemporary internet). Such a process is succinctly framed by an author of essay published in Rhizomes (a special issue 32 (2017) on meme culture edited by Talan Memmott and Davin Heckman) who insightfully remarks that “memes are ultimately not about unboundedness; rather, they are about commutability within tightly woven syntactic and paradigmatic structures.” Hence, memes as tiny balls of dense fabric tightly woven out of intertextual meanings travelling across platforms may be the way to negotiate freedom of imaginative play and inevitable constraints of the logics of corporate actors known as platforms. Their syntactic and paradigmatic structures are constituted by the system of language underlying our utterances as well as the system of power embedded in algorithmically-laden procedures governing what is being seen and circulated. Yet, once in a while, the unexpected space of agency is suddenly opening up—in those not so rare moments when collaborative power of imagination is harnessed and employed as a vehicle capable of setting narratives and storylines to travel fast and wide.

Works cited:

Losh, Elizabeth. Hashtag (Object Lessons), New York-London-Oxford-New Delhi-Sydeny: Bloomsbury Academic, 2019.

Memmott, Talan, and Davin Heckman, eds. 'Meme Culture, Alienation Capital, and Gestica Play', Rhizomes 32, 2017. http://rhizomes.net/issue32/memes/index.html

Mina, An Xiao. Memes to Movements. How the World’s Most Viral Media Is Changing Social Protest and Power. Boston: Beacon Press, 2018.

Nacher, Anna. '#BlackProtest from the web to the streets and back: Feminist digital activism in Poland and narrative potential of the hashtag”, European Journal of Women’s Studies, vol.28, issue 2, 2021 https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1350506820976900

Peterka, Jiři. “Kdo je skutečným otcem Internetu?”, CHIPWeek, no 34/95, 1995. http://www.earchiv.cz/a95/a534k700.php3

Rettberg, Jill Walker. Distributed Narrative. Telling Stories Across Networks, Paper presented at AoIR 5.0, Brighton, 21 September 2004. http://jilltxt.net/txt/Walker-AoIR-3500words.pdf

Scott, Mark. 'The shit-posting, Twitter-trolling, dog-deploying social media army taking on Putin one meme at a time', Politico, 31 August 2022. https://www.politico.eu/article/nafo-doge-shiba-russia-putin-ukraine-twitter-trolling-social-media-meme/

The Headquarters of North American Cimrman Society website, https://jaracimrman.wordpress.com/cimrman/

Wittig, Rob. Netprov. Networked Improvised Literature for the Classroom and Beyond. Amherst, MA: Amherst College Press, 2022.