This December, ebr has eight publications to share!

We have the pleasure of publishing select essays from the Arabic E-lit Conference in Dubai (February 2018), starting with N. Katherine Hayles’ “Literary Texts as Cognitive Assemblages: The Case of Electronic Literature” (published in ebr in August 2018). As the editor of this gathering, Dani Spinosa introduces these texts in her note “Essays from the Arabic E-lit Conference.” I encourage reading Spinosa’s thoughtful introduction.

Including Hayles’ work, the five essays of the gathering are Reham Hosny’s “Mapping Electronic Literature in the Arabic Context,” Serge Bouchardon’s “Towards Gestural Specificity in Digital Literature,” Doris Hambuch’s “Including E-Literature in Mainstream Cultural Critique: The Case of Graphic Art by Khaled Al Jabri,” and John F. Barber’s “Sound at the Heart of Electronic Literature.”

Dani Spinosa appears twice in this month’s issue of ebr, the second time in a riPOSTe to Hayles’ essay. In her riPOSTe, Spinosa explores how Hayles’ proposal of human-computer co-authorship expands our current notions of creativity and collaboration in literary production; when it comes to this symbiotic and communal work, Spinosa holds that computers can be considered creative.

Daniel Punday discusses N. Katherine Hayles’ newest book, Unthought: The Power of the Cognitive Nonconscious (Chicago UP, 2018) in his review, “Algorithm, Thought, and the Humanities.” Outlining how Hayles distinguishes between human consciousness and cognition, Punday shows in four sections that the ability of machines to make choices based on data constitutes nonconscious cognition—and describes the ensuing questions for scientific, social, and humanities research.

In the third installment on a 4-part series on the metainterface, its politics, and cultural practices and works that have emerged in response, this month, we publish a transcribed roundtable discussion by Christian Ulrik Anderson, Elisabeth Nesheim, Lisa Swanstrom, Scott Rettberg, and Søren Pold, on the topic of an emerging “aesthetics of infrastructure.” The discussion is fascinating—please have a look!

*

In her introduction to the essays from the Arabic E-lit Conference in Dubai, guest editor Dani Spinosa aligns the Arabic conference with the theme of the 2018 ELO Conference in Montréal, “Mind the Gap” by noting that furthering critical discussions of e-lit will depend on examining limitations and barriers to the study and reception of e-lit. Considering barriers of access in particular, Spinosa describes the way this month’s gathering brings together established and early-career scholars for a variety of perspectives and approaches “to address and work to correct issues of bias and access in this field.” In this sense, she points to N. Katherine Hayles’ contribution as a nexus of these discussions.

In the following section, the essays from the Arabic E-lit Conference will be discussed together as a gathering. In August 2018, we published N. Katherine Hayles’ essay “Literary Texts as Cognitive Assemblages: The Case of Electronic Literature.” Accompanying Hayles’ essay are selections from the conference.

In her essay “Mapping Electronic Literature in the Arabic Context,” Reham Hosny argues for much-needed information about Arabic e-lit in relation to the currently Western-focused understanding of and interest in e-lit. She describes online Arabic cultures and politics. In a comprehensive chart, she outlines texts by twenty different Arabic authors and two groups of Arabic poets. The discussion and breakdown that follows—including the need to understand the cultures and politics of the Arabic Internet—is enlightening to say the least, expanding e-lit’s popular definition and practice into other languages, authors, and texts.

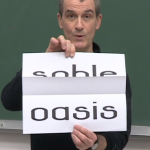

Serge Bouchardon’s essay “Towards Gestural Specificity in Digital Literature” examines the opportunity for readerly manipulations required for some interactive works (what he calls “digital creations”), which may imbue such texts with gestures of play that specify how we may think of e-lit in comparison to other forms of literature. Four of the digital creations he looks at are:

- Separation, a haptic e-lit application that splices two words (the top of one and the bottom of another) to create a new word;

- DO IT, an application in which readers choose text fragments that may prompt them towards traditionally un-readerly actions, such as shaking the reading device;

- Annie Abraham’s Don’t touch me, where the narrative option of “caress” (prompted by the cursor) stalls the story; and

- Loss of Grasp, which occurs in five languages, which shows and hides information based on cursor movement

Doris Hambuch’s “Including E-Literature in Mainstream Cultural Critique: The Case of Graphic Art by Khaled Al Jabri” argues to include e-literature in broader discussions of what counts as literature, which include print books but also printed graphic novels. She explores several examples of the cartoons of Emirati graphic artist Khaled Al Jabri, whose work depicts print books as “antidotes” to electronic media. Hambuch considers electronic literature as a form of electronic media that encourages readers to engage with the computer screen critically, thus thinking of interactive media as creative, insightful, and even political instead of purely as entertainment.

John F. Barber’s essay “Sound at the Heart of Electronic Literature” is grounded in the specificity of Arab storytelling, much of which has historically been oral and based on the author and “reader’s” interaction with sound. Thus, Barber explores sound as the throughway to approaching, understanding, and engaging with Arabic e-literature. He examines two Western e-lit works (34 North 118 West and Under Language) as well as three e-lit works from Arabic artist Mohamed Habibi in order to develop his argument, meanwhile ambitiously expanding e-lit as a “vehicle for exchanges in and across media, languages, and cultures.”

*

In her riPOSTe to N. Katherine Hayles’ essay “Literary Texts as Cognitive Assemblages: The Case of Electronic Literature,” Dani Spinosa focuses on Hayles’ descriptions of symbiotic (human-computer) authorship, pointing out the important ways in which this co-authorship allows for us “to reposition our relationship with technological devices.” The consequence of this way of thinking for fields such as electronic literature is such that digital literary production is considered collaborative work with creative authors and creative computers. Spinosa looks at Hayles’ case studies, describing of Nick Montfort’s Taroko Gorge, for example, that the algorithm used to generate the work’s content positions the computer as “active and agential.” Spinosa’s takeaway from Hayles’ arguments is that the human author is sometimes asked to relinquish control—a critical argument that exceeds Roland Barthes, to consider alternative active and agential platforms.

*

Daniel Punday reviews N. Katherine Hayles’ latest book Unthought: The Power of the Cognitive Unconscious (2018), noting the necessity of Hayles’ distinction between human consciousness and cognition, where the latter may involve nonconscious choice-making and “is a much broader faculty present to some degree in all biological life-forms and many technical systems” (14). In effect, consciousness is merely one part of our cognitive activity—a specification that Punday outlines as being crucial to understand in an age where machines and algorithms are often relied upon to make decisions based on data; the example Punday offers in this regard is the combat drone, a human-machine hybrid operator of warfare.

More common are the ways in which the technological cognitive nonconscious can control systems based on received and interpreted information. Here, Punday makes reference to Hayles’ interest in high-frequency trading, where the agency of algorithms to make high-stake choices in the stock market raise questions of ethics that Hayles explores culturally as well as academically. In particular, Punday notes that one of the primary goals of Unthought is to argue for philosophical and abstract humanities research to be more engaged with scientific facts. Far from preaching for STEM, Hayles shows that humanities research risks oversights if scientific inquiry is not integrated into the work, and also that humanities studies based purely on social relationships are lacking for being anthropocentric.

*

Our third installment of the metainterface series is “Always Inside, Always Enfolded into the Metainterface: A Roundtable Discussion,” featuring a discussion by Christian Ulrik Anderson, Elisabeth Nesheim, Lisa Swanstrom, Scott Rettberg, and Søren Pold that took place during an “EcoDH” seminar at the University of Bergen in June 2018. Exploring a potential “aesthetics of infrastructure” as well as its praxis, the transcribed discussion reveals several perspectives on the ethics of infrastructure and its invisibility—a continued theme from the previous two installments of this metainterface series. The participants offer different academic and creative examples that discuss this theme, including Timo Arnall’s Internet Machine (2014), Talan Memmott’s Digital Culture Lecture Tour (2014), sub-projects from Mark Marino and Rob Wittig’s ongoing Netprov project, and John Cayley and Daniel C. Howe’s The Readers Project.

At one point, Nesheim turns the conversation to concentrate on how everyday users can be more critical of the infrastructures behind interfaces, including through popular media platforms such as Skype, Netflix, Twitter, and Facebook, as well as services such as Uber and GPS technologies. Rettberg and Andersen relay this focus to the labourers of media infrastructures, which potentially include users as labourers of data generation. Here, Rettberg offers creative mediations of these circumstances, including Molleindustria’s Phone Story app (2011), which explores the life cycle of smart phones and the complicity of everyday users in participating in these cycles.

Rich with useful references, ideas, and exchanges, this discussion serves as a wonderful resource for readers who are interested in studies and mediations of interfaces, infrastructures, and the ethics of technoculture and technological labour.