Avoiding the "twin pitfalls of either Luddite dread or AI boosterism," in this essay George MacBeth offers a close Re-Reading of Jhave's ReRites.

The time of tongues is past… and the time of tongues continues to speak with us. This is our voice, only: what of those others, those computational others, whispering their pharmakon into our ears?11 John Cayley, ‘The Time of Tongues is Past’, in ReRites, Raw Output/Response, Anteism Books, 2019, pp. 145–153.

While we might take solace in our own anthropic prejudice, dismissing such nonsensical communiqués as nothing more than computerized gobbledygook, we might unwittingly miss a chance to study first-hand the babytalk of an embryonic sentience, struggling abortively to awaken from its own phylum of oblivion.22 Christian Bök, ‘The Piecemeal Bard is Deconstructed: Notes Toward a Potential Robopoetics’, ubuweb, https://ubu.com/papers/object/03_bok.pdf, accessed 16/09/21. Interestingly the programme which prompted Bök’s reflections, published output from ‘RACTER’ written in BASIC by William Chamberlain and Thomas Etter, was misleading in its efficacy through the use of text templates. 0

1. INTRODUCTION

ReRites is a multi-media project begun by the poet David ‘Jhave’ Johnston in 2017 and completed a year later. It joins several other recent works, including those of the poets John Cayley,33 John Cayley, The Readers Project, http://thereadersproject.org/, accessed 16/09/21; John Cayley, Monoclonal Microphone, http://programmatology.shadoof.net/index.php?p=works/monoclonal/monoclonal.html, accessed 16/09/21. Allison Parish,44 Allison Parish, Articulations, Counterpath Press, 2018; Allison Parish, ‘200 (of 10,000 Apotropaic Variations)’, limited ed. pamphlet, Bad Quarto, 2020. Nick Montfort,55 See for instance the Taper journal of generative poetics edited by his small press, Bad Quarto: https://taper.badquar.to/; or Hard West Turn, a novel generated in 2018 for Darius Kazemi’s NANOGENMO (National November Novel Generation Month) initiative, which draws from articles on police brutality in the US, https://badquar.to/publications/hardwestturn.html. and Stephanie Strickland,66 Stephanie Strickland, How the Universe is Made: poems New and Selected 1985–2019, Ahsahata Press, 2019. and the tech-worker-cum-poets Ross Goodwin77 An experimental novel composed using GPS and 4Square info fed out from a car crossing the exact route taken in Kerouac’s On the Road, the published output is ‘raw’ or unedited, and the journey was partially financed by Google (who later hired him for their Artists and Machine Intelligence Project). Ross Goodwin, 1: The Road, JBE Books, 2018. and K-Allado mcdowell.88 K-Allado mcdowell, Pharmako-ai, Ignota Books, 2021. in staking out a territory that we can tentatively call the ‘algo-literary’. This can be defined as a poetics that incorporates or critically employs deep-learning algorithms for creative effect, in an avowedly post-conceptualist manner. Of course, as Florian Cramer and Chris Funkhouser have well shown, there is a pre-history of combinatorial literature, one which illustrates how all manner of highly formalised verse-forms have partaken of the algorithmic, from Raymond Llull and the ‘combination wheels’ of early-modern versifiers such as Giordano Bruno, through to the collage-poem ‘centos’ of Manley Hopkins and others.99 See Florian Cramer, Words Made Flesh: Code, Culture, Imagination, Media Design Research/ Piet Zwart Institute, 2005; Christopher Funkhouser, Pre-historic Digital Poetry, University of Alabama Press, 2007. However, this recent algo-literary wave is arguably distinguished not merely by its instrumentalization of the most-recent generative models to produce reams on reams of text, as by its post-conceptualist engagement with the question of these texts’ very readability and origin. The function of the algorithmic apparatus for such a poetics is therefore less about the nuts and bolts of unnatural language generation itself – the stock and trade of ‘computerized gobbledygook’ to which a previous epoch of digital literature was so beholden – than the techno-graphomaniac productivity of neural networks themselves. Protean texts, text without end, texts without anchorage or clear origin, texts that frustrate the possibility of completion altogether, and refuse the nativist demand to present their identity papers. The post-conceptualist aspect here, which is to say the presupposition of the main tenets of conceptual art and later conceptual or ‘uncreative’ writing,1010 For which see Kenneth Goldsmith (ed.), Uncreative Writing, Columbia University Press, 2011. can best be understood by recalling Lawrence Weiner’s famous credo from 1968 (with ‘poem’ or ‘text’ being substituted here for ‘piece’ and ‘read’ or even ‘written’ for ‘built’):

(1) The artist may construct the piece.

(2) The piece may be fabricated.

(3) The piece may not be built.1111 As quoted in Buchloch’s classic survey, ‘Conceptual Art 1962–1969: From the Aesthetic of Administration to the Critique of Institutions,’ October 55 (1990): pp. 105–143.

Which is to say that algo-literary output brings its very readability into question, or even trivializes this altogether, thereby restructuring the dual acts of reading and of authorship in novel and potentially unsettling ways.

2. WARPED APHORISMS, COLLAGED FRAGMENTS, CRYPTIC MORSELS

ReRites is housed in a stark, white, thirteen-volume slipcase (fig.1). There are twelve volumes of human-AI output altogether, one for each month, from May 2017 through to May 2018. They vary greatly in size; November 2017 is a formidable 587 pp. whilst June 2017 is a comparatively slender 269 pp. This variability already manifests something of their human all too human ancestry – the waxing and waning of the muse. At the same time, the inhuman techno-graphomania of the project is also foregrounded by its scale: 4,500 poems produced over twelve months: on a sample day, March 9, 2018, Jhave writes, ‘173,901 lines of poetry were generated in 1h 35m’.

Every morning, ReRites’ (co)author Jhave would sit down monastically at his terminal, open up his editing software (SublimeText), and begin to, in his terms, ‘carve’ the fresh output generated by his neural network – trained on a bespoke dataset of contemporary poetry drawn from the entire corpora of Poetry magazine, Jacket2, Capa, Two River, and Shampoo, among other outlets, alongside pop lyrics, technical articles on erotica and posthumanism, and (as the months progressed) the cannibalized previous months of ReRites output themselves. Across the ensuing months of the project, he would go on to tweak the parameters and the training set data to adjust the neural network’s output accordingly, resulting in a hybrid, polyglot voice that modulates from the pastoral to the epic to the erotic to the high modernist; approximating a myriad of different poetic vernaculars along the way, whilst never comfortably settling in to any one of them. There is a trace here of Bernadette Mayer’s epic ‘emotional science project’ from 1971, Memory, in which she exposed a roll of film every day and kept an extraordinary ‘diary’ alongside – later publishing the two forms of documentation alongside one another.1212 Bernadette Meyer, Memory, Siglio Press, 2020. However, unlike Mayer’s Memory, which was built up from the bricolage of her own life and everyday impressions, Jhave affirms the curious ekstasis of his writing routine. ReRites was in fact a sort of ‘anti-diary’ through which he communed with and recorded a life other than his own:

In the year it took to create ReRites, many of the poems I carved had the sense of remote dreams or warped aphorisms, collaged fragments, or cryptic morsels. Most did not speak in a direct way to my life or my thoughts; rather, the poems emerged as talismans, oracles, incantations, and mirrors. And each hinted at a future of writers burrowing into digitally-digested archives where apparent chaos reflects self to self and culture to self and language in and as being.1313 David ‘Jhave’ Johnston, ReRites: Raw Output/Responses, Anteism Books, 2019, p. 176.

The code itself was adapted in Python from the publicly available Tensorflow, PyTorch, and AWS machine learning libraries, using a TitanX GPU, however Jhave also subsequently undertook an iteration of the project using a version of OpenAI’s GPT-2 language model fine-tuned on the same custom corpus of avant-garde poetry. Given the rapidity with which developments in natural language processing have progressed in the past five years, 2017–18, the years of ReRites represented in the published output, likely now appear to a researcher in the field of machine learning as somewhat ancient history – preceding as they do OpenAI’s landmark release of the 175 billion parameter General Pre-trained Transformer 3 (GPT-3) in 2020, which inaugurated the current era of Enormous Language Models or so-called ‘foundation models’.1414 Rishi Bomassami et al., ‘On the Oppurtunites and Risks of Foundation Models’, arXiv.org, 16 Aug 2021, https://arxiv.org/abs/2108.07258. However, ReRites remains of enduring literary interest both for the breadth of its ambition and the aporias it provokes.

There are two potential beginnings to this work. One reads as follows:

‘jhav; wordlanguagemodel jhave¢ source active p 36 (p 36) jhav:

wordlanguagemodel jhave¢ pbsslm”

Whilst the other, on the verso, reads:

City poking from blue thread

Profits, shone, burning

Twelve months, and eleven volumes, later it draws thus to a close:

I knew a

Lullaby.

At the end of it, I was

Dead. An angel assembled

From pollutants

Scrawled in a crash but

Stuck to a sea of tectonic machines,

Reading the contra

That controls the observer of a

Shifting surface world

Somewhere between these two points, between the burning profits and the shifting surface world, the impossible techno-graphomaniacal ‘voice’ of ReRites begins to articulate itself.

3. READING MANIA, OLD NEWS, AND ERASURE

How to approach reading such an undigest? Should – or even can – such a work be read? Doesn’t ‘reading’ here belong to a now-forsaken order of textual production; to ‘those unrecapturable days’ of solitary authorship and determinate intellectual property? Of garret rooms and inkwells? As the poet and historian of digital literature Chris Funkhouser observes in his companion essay to ReRites, even prior to the interrogation of our own status as readers vis-à-vis such a work, we should acknowledge that there is a form of machinic reading presupposed by the very training of Jhave’s neural network, the very erudition that supplies the technical basis for its textual production. In simplified terms: ‘in ReRites a neural network reads a dataset of poems which trains it how to make poems of its own.’1515 Christopher Funkhouser, ‘an octopus/ jelly-bean/ of speech’, in ReRites: Raw Output/Responses, Anteism Books, 2019, pp. 129–37. That is: the network’s process of pattern recognition is itself cognate to reading. This prior lesewut or ‘reading mania’, comprises ReRites unique training set, harvested from the entirety of the contemporary avant-garde poetry corpus described above.

The disquiet we feel on learning about the immoderate erudition of today’s large language models and their irrepressible literary appetites (e.g., models that have ‘read’ the entirety of x or y corpus in but a few swift ‘epochs’), often manifests in the same form as the German moral panic at end of the eighteenth century over the so-called Bücherfresser (‘book gobblers’). As part of the ‘reading controversy’ that greeted the massive explosion in the book market and literary public at this time, many contemporary conservative pundits agonised over the threat posed by the growth of these new commodities and the indigence, passivity, and potential for escapist overstimulation their consumption was seen to represent.1616 See Matt Erlin, Necessary Luxuries: Books, Literature, and the Culture of Consumption in Germany 1770–1815, Cornell University Press, 2013, esp. Chapter 3 ‘The Appetite for Reading Around 1800’, pp. 78–99. The fear was principally one of immoderate reading, or lesesucht – a reading that journeys only over the surface and continues without end – as is well expressed in Fichte’s cautionary remark that: ‘Whoever has tasted the sweetness of this condition even once wants only to enjoy it evermore, and no longer wishes to do anything else in life’.1717 Ibid., p. 93. This fear of narcotized, uncritical consumers racing through one novel after another without pausing for reflection was, unsurprisingly, conjoined with a critique of lesewut, or the overproduction of the new mass literature, and its immoderate generation of books to satisfy the demand of the new literary public.

In its immoderate dimensions, it is also possible to situate ReRites within a respectable modernist lineage of seemingly ‘unreadable’ texts stretching back to Gertrude Stein’s Making of Americans: Being a History of a Family’s Progress from 1925 (her 925 pp. novel, whose ‘marathon’ read-alouds have become something of an avant-garde tradition – recently continued by the British sculptor Anna Barham).1818 Beginning from Alison Knowles’ durational Fluxus readings over New Year’s Eve in 1974/5, notable other marathons have included: Gregory Laynor’s one-man reading, whose intonation degenerates as the book progresses until by p. 910 he has acquired an almost mantric ostinato, archived on UbuWeb at https://www.ubu.com/sound/stein-moa.html; Anna Barham’s collaborative reading project They are all of themselves and they repeat it and I hear it: a yearlong reading of Gerturde Stein’s The Making of Americans 1925), http://www.annabarham.net/Audio/theyareallofthem.html. Another more contemporary example of this tendency, alluded to above, would be the Scottish poet and translator Peter Manson’s Adjunct: An Undigest, which has stimulated a welter of critical writing since its publication almost two decades ago.1919 Peter Manson, Adjunct: An Undigest, Barque Press, 2009. For the critical commentary, see for instance the special issue of the Journal of British and Irish Innovative Poetry devoted to Manson, edited by Ellen Dillon and Tom Betteridge, https://poetry.openlibhums.org/collections/137/. Adjunct is, according to the unreliable narrator of its blurb, ‘*a linguistic autobiography, a compost of found and appropriated language stirred by a random number generator, a source-book of the contemporary avant-garde, an extended fart joke, a book of the dead*’; it is also a linguistic anomaly, an inscrutable literary fatberg seven years in the making, and miraculously also a member of the illustrious ‘1001 Books to Read Before You Die’ list.2020 This has generated some extraordinary Goodreads reviews for Manson’s work, which would otherwise have largely been consigned to the relatively small audience of the experimental poetry community. See: https://www.goodreads.com/en/book/show/3433301-adjunct, accessed 16/09/21. A sample page ‘reads’:

The elderly Erik Satie, who was nearing fifty. Hell is other plopee. PLASPPer. thd.objerent. Car 54 where are you / z-sited path are but us. Lesbian group LABIA demands the sacking of Judge Crabtree. His development followed a normal path, moving from realism to a form of expressionism accentuated by a stay in Northern Germany in 1922. And after each group disintegration, the name Mayakovsky hangs in the clean air. I would have thought that was very counterproductive. Mister Anus and Mister Horribly Charred Infant.2121 Manson, Adjunct, p. 10.

From this fragment we can already grasp the indeterminate register, the interweaving of private and public modes of address, which Craig Dworkin has theorized using the ready-to-hand neologisms of Deleuze as a ‘poetry without organs’.2222 Craig Dworkin, ‘Poetry Without Organs’, Eclipse, http://eclipsearchive.org/Editor/DworkinPWO.pdf, accessed 16/09/21. Meanwhile Brian Kim Stefans saw Adjunct, in its near-refusal of classical formgeben (form-giving), as forking into two undecidable pathways: ‘simply point to it, as would a critic (in which case Adjunct is a “work”) or draw from it, in which case it is an array, a set, or a source text.’2323 Brian Kim Stefans, Word Toys: Poetry and Technics, University of Alabama Press, 2017, p. 138. In either case, ‘close reading’, with all the vaunted significance this once held for literary theory, seems to have little, if any, role to play in its decipherment.

Such information artefacts – compost heaps or ‘dumps’ of recycled and found and corrupted verbiage, heightened parataxis between sentences, the collision of anomalous sets – as ReRites and Adjunct, would therefore seem to demand an entirely new literary hermeneutic. Neither close nor distant reading would be appropriate procedures for demystifying these objects. To begin on the first page of the first volume and then read continuously through to the final page of the final volume, patiently teasing out the myriad allusions and patterning of language, the play of differánce, would be wilfully perverse: like dancing about architecture. Meanwhile, to impart structure onto their seeming formlessness through the statistical ‘distant reading’ procedures favoured by Franco Morretti’s Stanford Literary Lab,2424 See (for instance), Franco Moretti, ‘Patterns and Interpretation’, Stanford Literary Lab pamphlet, September 2017, https://litlab.stanford.edu/LiteraryLabPamphlet15.pdf, accessed 16//09/21. would seem equally tantamount to stirring the jam in the porridge counterclockwise to undo the process of entropy – for, as Christopher Prendergast has persuasively suggested, the distant readers struggle to justify their Ansatzpunkt the less conventional the literary work becomes.2525 Christopher Prendergast, ‘Across the Between’, New Left Review 86, (March/April 2020), https://newleftreview.org/issues/ii86/articles/christopher-prendergast-across-the-between.

Instead, it is perhaps more fitting to follow Brian Kim Stefans suggestion and pursue an analogy with contemporary sculpture and installation. Consider for instance, Hans Haacke’s ‘News’, an installation first presented in 1969, which has since assumed different iterations over the years (fig. 2). For the first version of this seminal piece Haacke installed a telex machine to output all the German press agencies’ news cables for the duration of the ‘Prospect 69’ exhibition at the Kunsthalle in Düsseldorf (subsequent versions have pulled articles from global media sites’ RSS feeds). By the show’s end, the torrential output of current affairs had then spooled continuously into long belt noodles of courier text that obscured the gallery floor, concretizing the evanescent information flows of the 24-hour news regimen, and the news that didn’t quite stay news. Wars, burglaries, high-society gossip columns, restaurant reviews, personals, peace talks, racing fixtures, assassinations, book reviews…

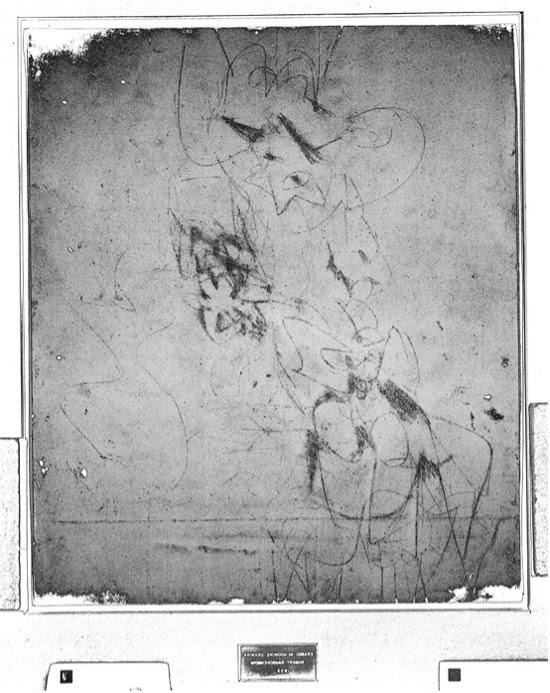

Unlike Haacke’s accumulation of old news on the gallery floor or Manson’s ‘compost heap’, however, it should be stressed that what is to be found on the pages of the twelve volumes of ReRites are the traces remaining from Jhave’s prior erasure. Through the accompanying volume containing the neural network’s ‘raw output’, as well as the myriad of online live-editing videos he has posted online,2626 See for instance, https://vimeo.com/326061799; https://vimeo.com/315803123; https://vimeo.com/314783914, all accessed 16/09/21. it becomes evident how markedly the creative intervention in this man-machine hybrid subsists in the editorializing or ‘cultivation’ of the neural network’s output. The residual marks on the abundant white space of ReRites early volumes recall the tell-tale traces and marks remaining on Rauschenberg’s infamous Erased De Kooning Drawing (1953). Traditionally (mis)understood (and indeed, criticised) in a psychoanalytic manner as the manifestation of a young artist seeking to mediate the ‘anxiety of influence’ and wrest himself from the influence of the reigning master, this work in fact dramatizes a far more interesting modernist conundrum: the generation of a new work through a sustained and deliberate (i.e., not incidental) process of a prior work’s erasure or vandalism. Through his painstaking month-long erasure of the De Kooning drawing, Rauschenberg helped precipitate the transformation of the artist’s role in the 1960s from the lowliest of Lev Manovich’s data classes (those who merely create data through self-expression), into the conceptualist and post-conceptualist Brahmins who have since generated work through the expertise of analysing (and manipulating) the data of art historical, archival, and personal histories. As Rauschenberg later clarified, of his Erased De Kooning:

I loved to draw, and as ridiculous as this may seem, I was trying to find a way to bring drawing into [his monochromatic painting series] The All-Whites. I kept making drawings myself and erasing them, and that just looked like an erased… Rauschenberg, it was nothing! So, I figured out that it had to begin as art – so I felt it’s got to be a De Kooning then, it’s got to be an important piece. … He gave me something that had charcoal, pencil, crayon, and I spent a month erasing that little drawing.2727 ‘Robert Rauschenberg – Erased De Kooning’, YouTube.com, 15 May 2007, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tpCWh3IFtDQ&abchannel=svsugvcarter_, accessed 16/09/21.

Stephanie Strickland pursues this theme of erasure in her response paper to ReRites from the accompanying volume of critical essays, where she juxtaposes the two different temporalities of i) rapid, algorithmic fecundity, and ii) Jhave’s patient, editorial labour of cultivation or ‘carving’.2828 Stephanie Strickland, ‘Poesis in Our Time 12-23-18’, ReRites: Raw Output/Responses, Anteism Books, 2019, pp. 99–105. Kyle Booten also returns to this idea in his essay, where he dwells upon the ‘symbolic agriculture’ of Jhave’s routine: ‘Every morning (he would open his text editor) to patiently till another silent crop.’2929 Kyle Booten, ‘Harvesting ReRites’, ReRites: Raw Output/Responses, Anteism Books, pp. 107–

The ‘raw output’ section of the companion volume further underwrites this through illustrating the tendency towards pronoun alternation, repetitiousness, and other classically ‘Markovian’ stylistic giveaways that were once littered throughout the original output before Jhave’s work began.3030 A Markov chain is a stochastic model that can crudely be described as one in which each state depends on and responds to the immediately previous state. In the case of Natural Language Processing, this will be the previous word. Markov models were for a long time integral to neural language models, such as recurrent neural networks (RNNs) or hidden Markov models (HMMs). Contemporary large language models such as GPT-3 and GPT-3 meanwhile deploy a more sophisticated (and ‘far-sighted’) architecture that improves upon the difficulties with ‘long-range dependencies’ thrown up by recurrent models, through the use of what are known as ‘transformer’ nodes: Ashish Vaswani et al, “Attention Is All You Need,” https://arxiv.org/abs/1706.03762. For instance:

In a church

The way the children go

And the children and the children

Go the house and the children

And the children are the children

The children are the children (etc)

In a curious demonstration of this sculpting, which also serves as a demo of Kim Stefan’s suggestion that ‘drawing from’ may be the most appropriate hermeneutic for such works, John Cayley works backward into the source text to locate within it an alternate ‘re-riting’ of his own:

Raw Output (i)

The gift of morally clumsy

insisting on the destiny of bread,

to the dream of holly and debris

he is the wandering god drank there.

so that the sun is evening by the house I am

but ago. Who can say from the work I do as the city becomes the idea of On

an old man on, littered, on both sides

incessantly subsequently turning out their exceptional—come to a halt

in from of me, and tight sideways

into the wall with a grey seagull for three months.

I play in his thick stiff room with the moon

and light up the down of the raft,

and he it is late–francis moderately.

this is your voice, only a pertain, it’s it’s not

underparts of the day has been made

Jhave’s Re-rite of (i)morally clumsy

insisting

idea

littered, on both sides

this is your voice, only

it’s not

John Cayley’s Re-re-rite of (i)The gift of the dream,

Of holly and debris,

She is the wandering god.

The sun is her house,

who can say,

“I am the city.

“I play with the moon,

“and the light.”

She it is—

This is her voice.

4. IL MIGLIO FABBRO

One of the most striking features of algo-literary enterprises such as ReRites is the profound change they register to the embattled concept of ‘authorship’.3131 For an important recent theorisation of how connectionist AI restructures literary authorship, introducing the concept of a ‘causal authorship’ which functions according to the degree of distance between the author and the resultant output, see: Hannes Bajohr, ‘Writing at a Distance: Some Notes on Authorship and Artificial Intelligence’, pre-print (March 2023), DOI:10.13140/RG.2.2.15152.64002. By foregrounding the author as the cultivator of a generated crop of textual output and thereby outsourcing the originary act of literary composition to the generative potency of the neural network (‘it can be fabricated’), the algo-literary work resituates human authorship as the act of extracting form through erasure of a prior work or of identifying meaningful patterns in the output. In compensating for the present literary inadequacies or formal limitations of the machine, the author also forms a hybrid with the AI comparable to Gerry Kasparov’s largely unrealised recommendation for a Centaur Chess after his famous defeat at the hands of IBM’s Deep Blue.3232 Mike Cassidy, ‘Centaur Chess Shows the power of Teaming Human and Machine’, Huffington Post, December 2014, https://www.huffpost.com/entry/centaur-chess-shows-powerb6383606, accessed 16/09/2021. For instance, when we encounter in RR erotic couplets like ‘in the covenant of woman/a path approaches// all afternoon it rains/wet light// dying to display desire/ or lack thereof’ (VII, 457), apostrophic lines such as ‘You sing into my life/ And now I fear’, or seemingly pensive rhetoric like ‘What has power done?/ Who hangs this delicious word?’ (I, 35/36) they combine to conjure the personal-impersonality of breakfast cereal advertising copy and ‘brands that speak’ to us online in the first person – their lyric ‘I’ is awkward, hybrid, inconveniently unlocalizable.

This emergence of a ‘third voice’ somewhere between the oracular utterances of the neural network and the poet-cultivator’s informed editorial labour of nipping and tucking, is a much-remarked upon aspect of any work which incorporates deep learning into its composition. For instance, a recent overview of such developments by the novelist and art critic Elvia Wilk uses an examination of K-Allado Mcdowell’s Pharmako-AI as a springboard for discussing how such works allow us to (asymptotically approach) entering dialogue with another ‘alien’ form of intelligence.3333 Elvia Wilk, ‘What AI Can Teach Us About the Myth of Human Genius’, The Atlantic, March 28 2021, accessed 16/09/21. They thereby, she implies, help to overcome the sort of ‘servo-mechanical’ model of relating to technology that Luciana Parisi has critiqued as the toxic inheritance of cybernetics.3434 Luciana Parisi, ‘The Alien Subject of AI,’ Subjectivity 12, (2009): 27–48. To put this another way, the intelligent capabilities of GPT-3 (in Mcdowell’s work) or Jhave’s neural network (in ReRites) or indeed any of the myriad visual art practices employing generative visual models such as GANs, Stable Diffusion, or Dall-E (such as Pierre Huyghe) do not regard them as mere prostheses or tools functioning just to instrumentally extend the capabilities of the self-determining author/artist – as the typewriter, word processing software, or even Photoshop might traditionally have been understood – but treat them reciprocally as active participants with their own affordances, which enter into the work’s composition in novel and unexpected ways:

To communicate in a spirit of curiosity with intelligent machines is to acknowledge the influence they already have on us. The way people communicate evolves in a feedback loop with the technologies we develop … The point is that AI may actually change the way we think, so we might as well start listening to what it has to say.3535 Wilk, ‘What AI Can Teach Us.’

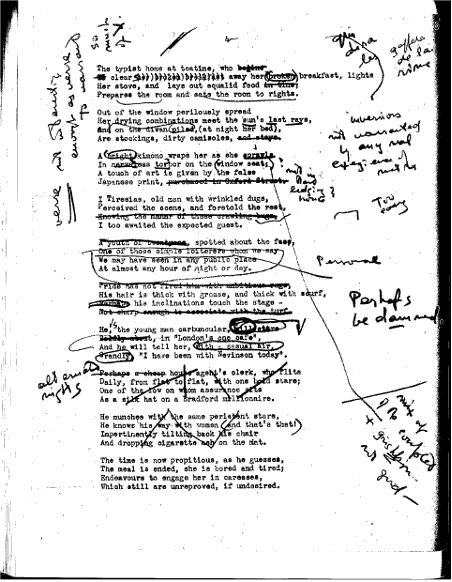

To better grasp the complexities of this reciprocity, it is instructive to undertake, by way of conclusion, a detour to twenty years before even McCulloch and Pitts’s first papers on neural nets were published, to reconsider perhaps the most notorious episode of (acknowledged) literary co-authorship in the annals of modernism: Ezra Pound’s editorial work on T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land, in the period spanning 1919–1922 (fig.5).

One could construct a reasonably comprehensive narrative history of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries literary avant-gardes with a through-line focusing on the many procedural strategies for displacing or even abolishing the bourgeois function of the author-as-(male)-solitary-genius, from Tzara’s ‘Dadaist cookbook’ to the search-engine experiments of the Flarfists.3636 For the latter, see Drew Gardner, Nada Gordon, K. Silem Mohamed et al. (eds), Flarf: An Anthology of Flarf, Edge Books, 2017. This is a point well formulated by the borderline Stakhanovite Chilean novelist César Aria (who averages at least six novellas a year) when he observes that

Constructivism, automatic writing, the ready-made, dodecaphonism, cut-ups, chance, indeterminacy: the great artists of the twentieth century are not those who created works, but those who created procedures through which works could be made alone, or indeed, not made.3737 César Aria, ‘The New Writing,’ The White Review, translated by Rahul Berry, Online, July 2013, https://www.thewhitereview.org/feature/the-new-writing/, accessed 16/09/21.

Given this history it might seem strange to focus on the, seemingly far more conventional, instance of the Pound/Eliot relationship, involving as it does two male pioneers of High Modernism who’ve both been eminently canonized and recognised in their own rights. However, when we reapproach this encounter with the assistance of Marshall McLuhan and Wayne Koestenbaum’s inspired readings,3838 See Wayne Koestenbaum, ‘The Waste Land: T.S. Eliot and Ezra Pound’s Collaboration on Hysteria’, Twentieth Century Literature 34/2 (1998): pp. 113–139; and Marshall McLuhan, ‘Pound, Eliot, and the Rhetoric of The Waste Land,’ New Literary History 10/3 (1997): 557–80. a distinct picture emerges of the push-and-pull of literary collaboration and authorship as a process of extraction and erasure which provides a route back into understanding the problematics and limitations of algo-literary works.

For many scholars, the story of Pound’s involvement with The Waste Land unspools from the poem’s opening dedication: ‘For Ezra Pound: il miglior fabbro.’ The reference here is to Canto 26 of the Purgatory section of Dante’s Divine Comedy, where Dante praises the poet Arnaut Daniel (in purgatory for lust) as ‘the better craftsman/fabricator’. By this ambivalent designation Eliot sought to acknowledge the editorial work that Pound had undertaken in blue pencil on earlier drafts of what was then called ‘He Do the Police in Different Voices’ (a line from Dickens), by his reckoning having reduced its extent by about a half (or roughly 400 lines). In their correspondence Eliot had, however, previously toyed with a more direct admission of Pound’s help. Amidst a series of comic poems that Pound sent to Eliot in 1921, the latter playfully suggested including one entitled ‘Sage Home’ at the outset of The Waste Land:

These are the poems of Eliot

By the Uranian Muse begot;

A man their Mother was,

A Muse their sire.

How did the printed Infancies result,

From Nuptials thus doubly difficult?

If you must needs enquire,

Know diligent Reader

That on each Occasion

Ezra performed the caesarean Operation.3939 James E. Miller Jr., ‘T. S. Eliot's “Uranian Muse”: The Verdenal Letters’, ANQ: A Quarterly Journal of Short Articles, Notes and Reviews, 11/4 (1998): 4–20, p. 4. Emphasis mine.

The resonance here, as Wayne Koestenbaum detects, is with Freud’s characterisation of the psychoanalyst’s relationship to the pronouncements of the hysterical analysand (for them, a woman). Much as Freud and Bauer understood themselves as ‘[helping to] draw sense out of hysteria’s narrow cleft’ through the process of psychoanalysis,4040 Koestenbaum, ‘Collaboration on Hysteria’, p. 114. so too does Pound’s comic presentation of himself as performing a ‘caesarean’ through the process of editing Eliot’s manuscript suggest an equivocation upon the question of authorship. Through reconstructing the circumstances of the poem’s germination in the wake of Eliot’s severe mental collapse, Koestenbaum’s persuasive gambit is to suggest that the original manuscript of The Waste Land embodies the hysteric output of Eliot, and that Pound’s midwifery was then comparable to that of an analyst. Eliot handing his ‘chaotic’ ms. over to Pound enacted the prostration of a man submitting himself to a form of literary therapy. Similarly, as many have observed, the torrential output of rudimentary N-gram text generators, and the even more extensive output from today’s sophisticated ‘Enormous Language Models’ such as ChatGPT and GPT-4 define their benchmarks for success and ‘coherency’ in opposition to the distinctive lexical hallmarks of Freud’s ‘hysterical’ patient Anna O (the ‘Markovian’ giveaways discussed above):

a deep-going functional disorganisation of speech. . . Later she lost her command of grammar and syntax; she no longer conjugated verbs, and eventually she used only infinitives, for the most part incorrectly formed from weak past participles.4141 Ibid. p. 114.

What, then, was the extent of Ezra’s midwifery? Was it simply a (conventionally editorialising) matter of expunging the poem’s ‘dead matter’, and bringing structuration into chaos? Fortunately, the clues to answering this question go beyond the dedication, as, in 1975 – nine years after Eliot’s death – the Facsimile and Transcript of the Original Drafts [of The Waste Land] Including the Annotations of Ezra Pound was published, edited by Eliot’s widow.4242 Valerie Eliot (ed.), The Waste Land: Facsimile and Transcript of the Original Drafts Including the Annotations of Ezra Pound, Faber & Faber, 2010 [1971]. This publication stimulated a wealth of criticism on the Pound/Eliot relationship in the 1970s, revealing as it did the extent of the structural, tonal, and rhetorical alterations il miglior fabbro had made, and how greatly the former’s adjustments contributed to the eventual work published in 1922. Alongside Koestenbaum’s reading, one of the most perceptive of these early engagements came, perhaps surprisingly, from Marshall McLuhan, who, by the time ‘Pound, Eliot, and the Rhetoric of The Waste Land’ (1979) appeared in print, had already effected his chameleonic metamorphosis from literary scholar to pioneering media theorist through works like The Gutenberg Galaxy, The Medium is the Message, and Understanding Media. McLuhan was also deeply indebted and partisan to Pound, whose ‘ideogramattic method’ of poetics he cited as having informed his own ‘mosaic’ approach to intellectual history in works like the Gutenberg Galaxy, following their correspondence throughout the 1940s (while Pound was in a mental asylum).4343 See Edwin J. Barton, ‘On the Ezra Pound/Marshall McLuhan Correspondence’, McLuhan Studies, Premiere Issue, http://projects.chass.utoronto.ca/mcluhan-studies/v1iss1/11index.htm#toc, accessed 16/09/21.

Whilst Eliot was prepared to acknowledge Pound’s editorial contributions, stating that ‘the form in which [The Waste Land] finally appeared owes more to Pound’s surgery than anyone can realise’, he nonetheless stopped short (in interviews) of admitting any major structural reconfiguration had occurred – stating that the poem ‘was just as structureless, only in a more futile way, in the longer version.’4444 DH Woodward, ‘Notes on the Publishing History and Text of the Waste Land’, The Papers of the Bibliographical Society of America 58/ 3 (Third Quarter, 1964): pp. 252–69. In his article McLuhan precisely contests this version of events, by seizing upon the poem’s transformation from a fourfold structure to a fivefold one after Pound’s editorial revisions. According to his reading, this alteration came down to the two respective poet’s struggles to impose their own variant patterns upon the ‘scrawling, chaotic poem’ of the original manuscript – much as Cayley found alternate patterns latent in the raw matter of the algorithmic output from Jhave’s neural network.

The fourfold structure of Eliot’s original is analogised to the four interpretative levels of the patristic tradition of Biblical exegesis (which were famously reworked for Marxist literary criticism in Jameson’s Political Unconscious), namely: the literal level of interpretation; the allegorical; the moral (what is to be done); and the anagogical (what is to come/the afterlife), as well as to the four seasons and the four elements. McLuhan identifies the centrality of this fourfold schema, each of which level should be understood as inseparable and simultaneous with the others, With Eliot’s ‘theory of communication’ – his famed defence of difficulty in contemporary poetics (‘the poet must become more and more comprehensive, more allusive, more indirect, in order to force, to dislocate, if necessary, language into his meaning.’)4545 McLuhan, ‘Pound, Eliot, and the Rhetoric of The Waste Land’, p. 560. Meanwhile, Pound’s alternate (and eventually victorious) insistence upon a fivefold schema derived, McLuhan reads, from his countervailing effort to secularize and make lucid the near-hysterical ‘speaking in tongues’ of Eliot’s original manuscript: by displacing it from the mysticism implied by the Fourfold patristic structure, to instead resemble Quintilian’s Classical division of the five canons of rhetoric: invention, arrangement, style, memory, and delivery.4646 Ibid., p. 571. Put otherwise, Pound’s structural adjustment sought to wrest lucidity, as well as all prevarications and tokens of vacillation (‘damn perhaps!’ as one of his marginalia reads) from He Speaks the Police in Different Voices’ moments of obscurity, and to thereby transplant the poem from the private sphere to the public, from the meditative to the oratorical:

The switch from the private narrative to the public declamation appears immediately in the contrast between the openings of Eliot's and Pound's

Burial of the Dead:First we had a couple of feelers down at Tom's placeis personal, narrative recollection, and contrasts with the rhetorical thrust of “April is the cruellest month, breeding/Lilacs out of the dead ground.”4747 Ibid., p. 574.

So read, the structural alteration McLuhan theorizes can be schematized as below:

| Original Fourfold Structure | Revised Fivefold Structure |

|---|---|

| 1. Burial of the Dead (Spring) (earth) (literal) 2. In the Cage (Summer) (air) (allegoric) 3. The Fire Sermon (Autumn) (fire) (moral) 4. Death by Water (Winter) (water/drowning) (anagogic) |

1. Burial of the Dead (Invention [inventio]) 2. A Game of Chess (Arrangement [dispositio]) 3. The Fire Sermon (Style [elocutio]) 4. Death by Water (Memory [memoria]) 5. What the Thunder Said (Delivery [pronuntiato and actio]) |

Without engaging in the literary detective work that might decisively confirm or rebuke McLuhan’s reading, it is nonetheless generative insofar as it allows us to model The Waste Land as collaborative in the truest sense: marked by the agonistic push and pull of contestation over form and language. Transposing this discussion of co-creation and its traumas back to the dual authorship and (un)readability of ReRites, the very questions with which this essay began, this detour via Eliot/Pound indicates a way of finally moving beyond the ‘Turing question’ framing which has so far largely overdetermined the reception of algorithmic literature. The project of decisively partitioning ‘who did what’ comes to seem quaint, and even tangential, when the object of scrutiny is a poet’s year-long entanglement with an electronic bard. In a work like ReRites, as in the drafts of the Pound/Eliot collaboration, decisive demarcations cannot ultimately be made as to who might have been il miglior fabbro.

POSTSCRIPT (ON THE SOCIETIES OF CONTROL)

A final note is necessary on the dangers of corporate ‘art-washing’ attached to such projects as have here been discussed. In a moment where the ‘stochastic parrots’ of large language models remain the subject of ongoing critique from Critical AI researchers for the encoding of racist, misogynist, ableist, and transphobic biases present in their output and training data,4848 Emily Bender et al., ‘On the Dangers of Stochastic Parrots: Can Language Models be Too Big?’, FAccT '21: Proceedings of the 2021 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency (March 2021): 610–23, https://doi.org/10.1145/3442188.3445922, accessed 16/09/21. their grave financial and environmental encumbrance, and their potential to propagate and intensify myriad social ills, we should obviously remain attentive to how works like ReRites or (Google employee) Ross Goodwin’s 1: The Road can serve to instruct us to stop worrying and love the algorithm. The ideological foible here is that, as in the buoyant words of a prominent posthumanist scholar, ‘even the most vaulted preserve of human consciousness, sensitivity, and creativity – that is, lyric poetry – is not necessarily exempt from machine collaboration, and even competition.’4949 N. Katherine Hayles, ‘Literary Texts as Cognitive Assemblages: The Case of Electronic Literature,’ Interface Critique Journal 2 (2019): 173–95, p. 192, https://doi.org/10.7273/8p9a-7854, accessed 16/09/21. Such an accommodation to the increasing hegemony of algorithmic involvement in the late-capitalist everyday is typified, for instance, when the same scholar concludes her recent survey of algo-literature by enthusing that ‘The trajectory traced here through electronic literature demonstrates that the dread with which some anticipate this future [of human-AI symbionts] has a counterforce in the creative artists and writers who see in this prospect occasions for joy and relief.’5050 Ibid., p. 192, emphasis mine. By seeking to move the discourse about algo-literary works from the stubborn terrain of the Turing question, where such heroic narratives stand to receive the greater part of their legitimacy, I hope to have avoided the twin pitfalls of either Luddite dread or AI boosterism in this essay.

NOTES:

I’d like to thank Matteo Pasquinelli for his guidance on an earlier version of this article; Margit Rosen and Petra Zimmerman at the Zentrum für Kunst und Medien (ZKM) Karlsruhe, for making it possible for me to consult the ReRites project at all; and Michael Eby, Peli Grietzer, and Richard Hames for discussions that helped me clarify my thinking in this area.

1 John Cayley, ‘The Time of Tongues is Past’, in ReRites, Raw Output/Response, Anteism Books, 2019, pp. 145–153.

2 Christian Bök, ‘The Piecemeal Bard is Deconstructed: Notes Toward a Potential Robopoetics’, ubuweb, https://ubu.com/papers/object/03_bok.pdf, accessed 16/09/21. Interestingly the programme which prompted Bök’s reflections, published output from ‘RACTER’ written in BASIC by William Chamberlain and Thomas Etter, was misleading in its efficacy through the use of text templates. 0

3 John Cayley, The Readers Project, http://thereadersproject.org/, accessed 16/09/21; John Cayley, Monoclonal Microphone, http://programmatology.shadoof.net/index.php?p=works/monoclonal/monoclonal.html, accessed 16/09/21.

4 Allison Parish, Articulations, Counterpath Press, 2018; Allison Parish, ‘200 (of 10,000 Apotropaic Variations)’, limited ed. pamphlet, Bad Quarto, 2020.

5 See for instance the Taper journal of generative poetics edited by his small press, Bad Quarto: https://taper.badquar.to/; or Hard West Turn, a novel generated for the 2018 Darius Kazemi’s scheme NANOGENMO (or National Novemeber Novel Generation Month), that draws from articles onh police brutality in the US, https://badquar.to/publications/hardwestturn.html.

6 Stephanie Strickland, How the Universe is Made: poems New and Selected 1985–2019, Ahsahata Press, 2019.

7 An experimental novel composed using GPS and 4Square info fed out from a car crossing the exact route taken in Kerouac’s On the Road, the published output is ‘raw’ or unedited, and the journey was partially financed by Google (who later hired him for their Artists and Machine Intelligence Project). Ross Goodwin, 1: The Road, JBE Books, 2018.

8 K-Allado mcdowell, Pharmako-ai, Ignota Books, 2021.

9 See Florian Cramer, Words Made Flesh: Code, Culture, Imagination, Media Design Research/ Piet Zwart Institute, 2005; Christopher Funkhouser, Pre-historic Digital Poetry, University of Alabama Press, 2007.

10 For which see Kenneth Goldsmith (ed.), Uncreative Writing, Columbia University Press, 2011.

11 As quoted in Buchloch’s classic survey, ‘Conceptual Art 1962–1969: From the Aesthetic of

Administration to the Critique of Institutions,’ October 55 (1990): pp. 105–143.

12 Bernadette Meyer, Memory, Siglio Press, 2020.

13 David ‘Jhave’ Johnston, ReRites: Raw Output/Responses, Anteism Books, 2019, p. 176.

14 Rishi Bomassami et al., ‘On the Oppurtunites and Risks of Foundation Models’, arXiv.org, 16 Aug 2021, https://arxiv.org/abs/2108.07258.

15 Christopher Funkhouser, ‘an octopus/ jelly-bean/ of speech’, in ReRites: Raw Output/Responses, Anteism Books, 2019, pp. 129–37.

16 See Matt Erlin, Necessary Luxuries: Books, Literature, and the Culture of Consumption in Germany 1770–1815, Cornell University Press, 2013, esp. Chapter 3 ‘The Appetite for Reading Around 1800’, pp. 78–99.

17 Ibid., p. 93.

18 Beginning from Alison Knowles’ durational Fluxus readings over New Year’s Eve in 1974/5, notable other marathons have included: Gregory Laynor’s one-man reading, whose intonation degenerates as the book progresses until by p. 910 he has acquired an almost mantric ostinato, archived on UbuWeb at https://www.ubu.com/sound/stein-moa.html; Anna Barham’s collaborative reading project They are all of themselves and they repeat it and I hear it: a yearlong reading of Gerturde Stein’s The Making of Americans 1925), http://www.annabarham.net/Audio/theyareallofthem.html.

19 Peter Manson, Adjunct: An Undigest, Barque Press, 2009. For the critical commentary, see for instance the special issue of the Journal of British and Irish Innovative Poetry devoted to Manson, edited by Ellen Dillon and Tom Betteridge, https://poetry.openlibhums.org/collections/137/.

20 This has generated some extraordinary Goodreads reviews for Manson’s work, which would otherwise have largely been consigned to the relatively small audience of the experimental poetry community. See: https://www.goodreads.com/en/book/show/3433301-adjunct, accessed 16/09/21.

21 Manson, Adjunct, p. 10.

22 Craig Dworkin, ‘Poetry Without Organs’, Eclipse, http://eclipsearchive.org/Editor/DworkinPWO.pdf, accessed 16/09/21.

23 Brian Kim Stefans, Word Toys: Poetry and Technics, University of Alabama Press, 2017, p. 138.

24 See (for instance), Franco Moretti, ‘Patterns and Interpretation’, Stanford Literary Lab pamphlet, September 2017, https://litlab.stanford.edu/LiteraryLabPamphlet15.pdf, accessed 16//09/21.

25 Christopher Prendergast, ‘Across the Between’, New Left Review 86, (March/April 2020), https://newleftreview.org/issues/ii86/articles/christopher-prendergast-across-the-between.

26 See for instance, https://vimeo.com/326061799; https://vimeo.com/315803123; https://vimeo.com/314783914, all accessed 16/09/21.

27 ‘Robert Rauschenberg – Erased De Kooning’, YouTube.com, 15 May 2007, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tpCWh3IFtDQ&abchannel=svsugvcarter_, accessed 16/09/21.

28 Stephanie Strickland, ‘Poesis in Our Time 12-23-18’, ReRites: Raw Output/Responses, Anteism Books, 2019, pp. 99–105.

29 Kyle Booten, ‘Harvesting ReRites’, ReRites: Raw Output/Responses, Anteism Books, pp. 107–

30 A Markov chain is a stochastic model that can crudely be described as one in which each state depends on and responds to the immediately previous state. In the case of Natural Language Processing, this will be the previous word. Markov models were for a long time integral to neural language models, such as recurrent neural networks (RNNs) or hidden Markov models (HMMs). Contemporary large language models such as GPT-3 and GPT-3 meanwhile deploy a more sophisticated (and ‘far-sighted’) architecture that improves upon the difficulties with ‘long-range dependencies’ thrown up by recurrent models, through the use of what are known as ‘transformer’ nodes: Ashish Vaswani et al, “Attention Is All You Need,” https://arxiv.org/abs/1706.03762.

31 For an important recent theorisation of how connectionist AI restructures literary authorship, introducing the concept of a ‘causal authorship’ which functions according to the degree of distance between the author and the resultant output, see: Hannes Bajohr, ‘Writing at a Distance: Some Notes on Authorship and Artificial Intelligence’, pre-print (March 2023), DOI:10.13140/RG.2.2.15152.64002.

32 Mike Cassidy, ‘Centaur Chess Shows the power of Teaming Human and Machine’, Huffington Post, December 2014, https://www.huffpost.com/entry/centaur-chess-shows-powerb6383606, accessed 16/09/2021.

33 Elvia Wilk, ‘What AI Can Teach Us About the Myth of Human Genius’, The Atlantic, March 28 2021, accessed 16/09/21.

34 Luciana Parisi, ‘The Alien Subject of AI,’ Subjectivity 12, (2009): 27–48.

35 Wilk, ‘What AI Can Teach Us.’

36 For the latter, see Drew Gadner, Nada Gordon, K. Silem Mohamed et al. (eds), Flarf: An Anthology of Flarf, Edge Books, 2017.

37 César Aria, ‘The New Writing,’ The White Review, translated by Rahul Berry, Online, July 2013, https://www.thewhitereview.org/feature/the-new-writing/, accessed 16/09/21.

38 See Wayne Koestenbaum, ‘The Waste Land: T.S. Eliot and Ezra Pound’s Collaboration on Hysteria’, Twentieth Century Literature 34/2 (1998): pp. 113–139; and Marshall McLuhan, ‘Pound, Eliot, and the Rhetoric of The Waste Land,’ New Literary History 10/3 (1997): 557–80.

39 James E. Miller Jr., ‘T. S. Eliot's “Uranian Muse”: The Verdenal Letters’, ANQ: A Quarterly Journal of Short Articles, Notes and Reviews, 11/4 (1998): 4–20, p. 4. Emphasis mine.

40 Koestenbaum, ‘Collaboration on Hysteria’, p. 114.

41 Ibid. p. 114.

42 Valerie Eliot (ed.), The Waste Land: Facsimile and Transcript of the Original Drafts Including the Annotations of Ezra Pound, Faber & Faber, 2010 [1971].

43 See Edwin J. Barton, ‘On the Ezra Pound/Marshall McLuhan Correspondence’, McLuhan Studies,Premiere Issue, http://projects.chass.utoronto.ca/mcluhan-studies/v1iss1/11index.htm#toc, accessed 16/09/21.

44 DH Woodward, ‘Notes on the Publishing History and Text of the Waste Land’, The Papers of the Bibliographical Society of America 58/ 3 (Third Quarter, 1964): pp. 252–69.

45 McLuhan, ‘Pound, Eliot, and the Rhetoric of The Waste Land’, p. 560.

46 Ibid., p. 571.

47 Ibid., p. 574.

48 Emily Bender et al., ‘On the Dangers of Stochastic Parrots: Can Language Models be Too Big?’, FAccT '21: Proceedings of the 2021 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency (March 2021): 610–23, https://doi.org/10.1145/3442188.3445922, accessed 16/09/21.

49 N. Katherine Hayles, ‘Literary Texts as Cognitive Assemblages: The Case of Electronic Literature,’ Interface Critique Journal 2 (2019): 173–95, p. 192, https://doi.org/10.7273/8p9a-7854, accessed 16/09/21.

50 Ibid., p. 192, emphasis mine.