Rowan Wilken sets himself the challenge of theorizing the unrepresentable in relation to the architectural model of the diagram.

...the operation of the diagram, its function, as Bacon says, is to "suggest." (Deleuze, 1993: 194)

'Deconstruction,' Jacques Derrida writes, 'is inventive or it is nothing at all; it does not settle for methodical procedures, it opens up a passageway, it marches ahead and marks a trail' (Derrida, 1989:42). Within architectural theory, at least, this deceptively simple message appears to have been forgotten (if it was ever fully heeded). An act of amnesia hastened, it would seem, at the 1992 Anywhere conference in Yufuin, Japan. It was here that Derrida reputedly refused to 'outline a project for the new' for architecture (Speaks, 1998:28). One can only presume that this refusal, to name one reason among many possible reasons, was at least in part because, as noted above, the new is already present within deconstruction in the form of invention. Derrida also apparently refused to 'offer [the assembled] architects a clear way to convert deconstruction (as the theoretical protocol) into architectural form' (Speaks, 1998:28). For the architectural fraternity, this double refusal only served to fuel a 'growing and palpable disappointment with deconstruction' (Speaks, 1998:28). Not surprising, then, that deconstruction should subsequently fall out of architectural favour, replaced by, among other things, a renewed interest in diagrams.For example, see ANY, 23 (1998), Daidalos, 74 (October, 2000) and Peter Eisenman's Diagram Diaries (1999). Eisenman, it should be noted, does not entirely abandon Derrida in his embrace of the architectural diagram. For example, Derrida's reading of Freud's 'mystic writing pad' figures prominently in Eisenman's discourse on diagrams. This makes for an interesting point of comparison with cybercultural criticism, where this same essay by Derrida also figures prominently. See, in particular, Tofts and McKeich (1998).

Drawing together Derrida's interest in grammatology and the inventive, and contemporary architectural interest in diagrams, this paper proposes the notion of "diagrammatology."I am not the first to use this term. For example, in a 1981 essay on spatial form in literature, W. J. T. Mitchell makes the following argument for diagrammatology, which has some relevance for how I wish to employ the term here: 'Since we seem unable to articulate our intuitions or interpretations of formal characteristics in literature and the other arts except by recourse to "sensible" or "spatial" constructs (not just diagrams and not just visual forms), then why not do it explicitly, consciously, and, most important, systematically? If we cannot get at form except through the mediation of things like diagrams, do we not then need something like diagrammatology, a systematic study of the way that relationships among elements are represented and interpreted by graphic constructions?' (Mitchell, 1981: 622-623). Diagrammatology is understood here as a generative process: a 'metaphor' or way of thinking - diagrammatic, diagrammatological thinking - which, in turn, is linked to poetic thinking. This understanding is informed by contemporary architectural theory which conceives of the diagram as a 'temporary formulation of intentions still to be realized, a machine for learning and change,' a "heuristic method" (Confurius, 2000:5). This paper develops diagrammatology through example, by exploring three iterations of the (architectural) diagram. The first iteration is Derrida's choral grid diagram, which emerged from his reading of the chora section of Plato's Timaeus - a reading that framed his collaboration with the architect Peter Eisenman on Bernard Tschumi's Parc de la Villette project. The second iteration is the use Gregory Ulmer subsequently made of Derrida's choral diagram and reading of the Timaeus in the development of the genre of "mystory" and "heuretics" (the "logic of invention"). The third iteration uses the choral grid as a guiding figure for speculating on the intermingled nature of contemporary tele-technologies.

Choral Work

In 1983 the Swiss-French architect Bernard Tschumi won the international competition to design a new 125-acre park, Parc de la Villette, for the former slaughterhouse site in the northeast corner of Paris. Tschumi's successful scheme for Villette is organised according to a strict point-grid system, with each point appearing at 120-metre intervals and each marked by a bright red 10 x 10 x 10 metre 'neutral space' cube or Folie (Tschumi, 1987:ii). The program for Villette is dense in allusion, and includes an elaborate play on the various meanings of "folly/folie" as façade, madness, insanity, and was conceived in part as homage to Borges, Burroughs, Cocteau, Queneau, and Bataille, among others. Also included in the site are galleries and segments of a 'cinematic promenade' of gardens, many of which were designed by individual designers or in collaboration.

The best known of these collaborations is Tschumi's invitation to Peter Eisenman and Jacques Derrida to work together to design a garden within Villette Park. Six brainstorming sessions took place, during which Peter Eisenman's design team met with Derrida to develop a plan for a garden at Villette. Despite these sessions, no ultimate scheme was realised from this collaborative pairing; we will come to one of the many reasons for this in a moment.

In the first session, Derrida responded to Eisenman's invitation by providing the architect with a fragment of what was later to become a much longer reading of Plato's Timaeus, entitled "Chora." This partial text is reproduced in Kipnis and Leeser, 1987. A longer version of this text appears as 'khōra,' in Derrida, 1995: 89-127. Derrida's partial text examines 'a very enigmatic passage in the Timaeus' in which 'Plato discusses a certain [singularly unique] place' known as chora (also khora, khōra):

In Greek, chora means 'place' in very different senses: place in general, the residence, the habitation, the place where we live, the country. It has to do with interval; it is what you open to 'give' place to things, or when you open something for things to take place. [...] Chora is the spacing which is the condition for everything to take place, for everything to be inscribed. The metaphor of impression or printing is very strong and recognizable in this text. It is the place where everything is received as an imprint. There have been many interpretations of chora, typically reducing chora or projecting into chora various systems, Kant's for example. Chora resists all these interpretations. (Derrida, 1987: 9-10)

Having thus introduced the notion of chora to his co-collaborator, Derrida explains his own interest in it:

What interests me is that since chora is irreducible to the two positions, the sensible and the intelligible, which have dominated the entire tradition of Western thought, it is irreducible to all the values to which we are accustomed. [...] Chora receives everything or gives place to everything, yet Plato insists that in fact it has to be a virgin place, and that it has to be totally foreign, totally exterior to anything that it receives; so, in a sense, it does not receive anything - it does not receive what it receives nor does it give what it gives. (Derrida, 1987: 10)

In other words, Derrida explains, 'everything inscribed in it erases itself immediately, while remaining in it. It is thus an impossible surface - it is not even a surface, because it has no depth' (Derrida, 1987: 10).Or as Niall Lucy puts it, 'khora is the pre-philosophical, pre-originary non-locatable non-space that existed without existing before the cosmos. Something like that. Its singularity - and this is the point - is its very resistance to being identified; it is what philosophy cannot name.' (Lucy, 2004: 68)

Within the context of the Villette garden project, 'because chora is a sort of radical void (though not a void)' it is suggested that 'the project be simple, even empty' (Kipnis, 1987:139). As Jeffrey Kipnis points out:

Because of the role of the four elements - earth, air, fire and water - in Plato's text on chora, Derrida suggests they be symbolized in the project, sand for earth, light for fire, etc.' (Kipnis, 1987:139)

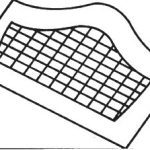

"Choral Work" is the title invented by Eisenman to describe this collaborative enterprise.Although 'collaboration' is a particularly problematic term for describing the Derrida/Eisenman 'Choral Work,' For Derrida, it is 'certainly not a collaboration. It is even less an exchange.' Rather, 'it is a double parasitic laziness,' or what Eisenman terms 'separate tricks.' See Derrida in Kipnis and Leeser, 1987: 111 and Eisenman in Kipnis and Leeser, 1987: 132-136. This issue is also discussed by Jeffrey Kipnis at length in the same volume, 137-160. For Derrida at least, this is a particularly apt and evocative title, with its layered evocations of chora, coral growth, and of choreography, choir and concert ('how could I not be reminded of the Music for the Royal Fireworks, of the chorale, of Corelli's influence, of that "architectural sense" we always admire in Handel') (Derrida, 1987: 95-101). Encouraged to contribute to this Choral Work some form of non-written text in order to distil his ideas - that is, to '"write", if one can say, without a word' - Derrida, 'improvising in the airport and then in the plane', produces the following sketch diagram (Derrida, 1987: 185).

Source: Bennington and Derrida, 1993: 406.

Accompanying this diagram is the following explanatory text:

I propose then [...] a metallic object, gilded (there is some gold in the passage of Timaeus on chora [...]), planted oblique to the sun, neither vertical nor horizontal, a solid frame resembling, at the same time, a framework (loom), a sieve, or a grille (grid), and also a stringed musical instrument (piano, harp, lyre): strings, stringed instrument, vocal chords, etc. And more than grille, grid, etc., it will have a certain rapport with a selective and interpretive filter, telescope, or photographic revealer, a machine, fallen from the sky, after having photographed; photographic filter and aerial view, which allows the reading and the screening (sifting?) of the three sites, the three layers (PDE, BT, LV). And more than a stringed instrument, it will make a sign (signify?) to the concert and the multiple chorale, the chora of Choral Works. (Derrida, 1987: 185)

As for explanatory interpretation, Derrida adds:

I think that nothing need be inscribed on this sculpture [...] except for possibly the title and a signature, unfigured somewhere. (Choral Work, by ... 1986) as well as one or two Greek words (Plokanon, seidmena, etc.) for discussion, among other things. (Derrida, 1987: 185)

The significance for the Villette project of Derrida's tutor-text and diagram can be revealed by turning to the second iteration of his reading of the chora in Plato's Timaeus. The second iteration - remembering that 'iteration always involves alteration'- is the use that has been made of Derrida's choral grid diagram and reading by Gregory Ulmer in his own researches into pedagogy, method, and invention (Tofts, 2004:59).

Chorography

The choral grid diagram - with the khōra as crible, sieve or sift - appears on the cover of Teletheory (1989), the second book in Ulmer's trilogy of invention. It also features prominently in the final section of Teletheory in Ulmer's example of a mystorical compilation: 'Derrida at the Little Bighorn'. Here, it would seem, Ulmer draws on Eisenman's insight that 'the quarry is a form of chora' to think through the "mystorical" significance of his father Walt's Sand and Gravel plant and the sieving screens used there to size gravel. Yet, in 'Derrida at the Little Bighorn' the notion of khōra and the choral grid are relatively minor elements in a kind of larger collage-montage text which draws together the three registers of the personal, the popular, and the academic.

It is not until Heuretics (1994), the third book in his trilogy of learning through discovery and invention, that Ulmer most fully incorporates Derrida's reading of khōra (and not just the sketch diagram Derrida hastily furnishes by way of illustration/distillation). In Heuretics, khōra holds a key place in Ulmer's development of 'the logic of invention' (heuretics) as a method for 'thinking and writing electronically' (Ulmer, 1994).In a later essay, Derrida's understanding of chora also holds a key place for Ulmer as the 'theory' for his 'Traffic of the Spheres' project which proposes a 'MEmorial' to those killed in car crashes. See Ulmer, 2001: 327-343. This same essay also provides a humorous account of Ulmer's perplexing dalliance with architectural education. 'I went to an academic advisor, a man wearing a hearing aid that seemed to give him considerable trouble. It functioned less as a prosthesis and more as a sign - "I am deaf." "I'm interested in the notion of Dasein," I told him. "Could you recommend a class I might take that would deal with Dasein in more detail?" He sent me to a course in architecture, an introduction to design. I have never been able to decide whether the advice was a mistake or not,' (331-332).

To begin with, Ulmer discovers that 'in order for rhetoric to become electronic, the term and concept of topic or topos must be replaced by chora' in its richer yet more enigmatic sense. (Ulmer, 1994:48) 'This,' Ulmer writes, 'is what I learned from Derrida' (48). "Place" (or more accurately khōra) subsequently holds twofold significance for Ulmer. First, it establishes a 'valuable resonance for a rhetoric of invention concerned with the history of 'place' in relation to memory' (39). Secondly, and working from an understanding of khōra as 'an area in which genesis takes place,' Ulmer sees an aspect of the task of his study to 'rethink the association of invention with place before "place" was split into topos and chora' (48 & 70).

Furthermore, in developing this heuretic method, the documentary record of the Eisenman/Derrida brainstorming sessions is read as a vital example of learning (and problem-solving) through invention. Ulmer suggests that in these sessions Derrida performs a kind of double manoeuvre. Derrida's contribution to the design 'is to propose to Eisenman the Platonic notion of space [...] not so much for their own sake but as a model for an invention strategy. Chora evokes an image of cosmological creation for a park of creativity' (63). At the same time,

Derrida mimed the unusual strategy of Socrates in this dialogue [in the Timaeus]. Rather than leading the discussion as he normally did, here Socrates placed himself in the position of listener, of active receiver or receptacle, of the discourse. [...] In the six planning sessions leading to the design of the folly, Derrida performs Timaeus and places himself in the same relationship to Peter Eisenman and his collaborators that Socrates held in relation to Timaeus and his companions. Derrida mimes Socrates, then, but it is not the interrogating Socrates of Platonism. In the first session, Derrida explains that he comes to the project with one idea that he wants to introduce into the process. (Ulmer, 1994: 64-65)

This "idea," as noted earlier, is the "impossible surface" of the chora.

An impossible surface: the perfect figure or "metaphor," it would seem, for an impossible project. As Ulmer puts it, 'the goal [with Villette] is not just to design a folly but to explore the invention process itself by means of this problem' (Ulmer, 1994: 66). Herein lays Ulmer's interest in the project: 'the impossibility of chorography is analogous to Eisenman's difficulty when he accepted chora as the program for his folly. He had to give architectural form to that which is unrepresentable' (66). It is, for Ulmer, a question of developing 'the method of no method (the possible impossible)' (67). The name he gives to this 'no-method' of invention, this 'illogic of sense,' is "heuretics." And if 'the general name for generating a method out of theory is heuretics, the particular name of the method is chorography' (39) - a method that is designed for 'writing and thinking electronically' in an age of electronic hypermedia (45). Ulmer characterises this method (after J. Hillis Miller) as thinking that is 'goal-directed without knowing exactly where it is going (it is tele-illogical)' (Ulmer, 1989: 19; Ulmer, 1994: 47); it is learning that is 'more like discovery than proof' (Ulmer, 1994: 57).

Ulmer's study has not been without criticism.For example: 'What a mystory ends up looking like [...] judging by "Derrida at the Little Bighorn," is a canonic literary memoir, beautifully written and fashionably discontinuous, and suitably apocalyptic in tone.' (Lucy, 2001:130) Even so, it has had lasting influence and remains a particularly important contribution in 'bringing into relationship the three levels of sense - common, explanatory, and expert' (Ulmer, 1989: vii); in developing a method (heuretics, chorography) for 'thinking electronically' (Ulmer, 1994: 45); and in its emphasis on the (il)logic of invention (and on rethinking the "place" of invention).Ulmer's project of developing a 'logic of invention' (heuretics) shares marked similarities with the work of the Canadian media theorist Donald Theall and his dual notions of an 'ecology of sense' (an adaptation of Gregory Bateson's theory of the ecology of mind) and 'the poetic' (an umbrella term for all forms of 'inventive cultural productions'). Curiously, these similarities have largely passed without remark, although they are playfully acknowledged in the title of the present volume with the two key concepts ('logic of invention' and 'ecology of sense') conjoined to form a kind of portmanteau title. On Theall's work, see in particular: Theall, 1995 and Tofts, 1997: 32-36.

Chorographical coincidence: the double winnow/window

To these first two iterations of the Derridean (architectural) diagram (and that is to say of diagrammatology in general), a third can be added. In the course of writing the preceding text, and throughout my own ongoing research into tele-technologies and issues of place and community, a certain chorographical coincidence has presented and continues to present itself to me. The coincidence is this: there is an uncanny similarity between the Derridean choral grid or sieve diagram and Microsoft's Windows XP icon. Indeed, the two can be overlayed, one on top of the other, to create a collage-montage, a kind of double winnow/window or filter/screen.

What is of interest in this coincidence is the capacity of the diagram - and of this particular diagram - 'to organize and suspend diverse kinds of information within a single graphic or set of graphic configurations' (Lobsinger, 2000: 22). To offer, that is, 'a logical and abstract means for representing, thinking about and explaining the complex dynamic and information dense conditions we confront'; to serve, in other words, as a conceptual tool 'that approximates our experience of the real' (Lobsinger, 2000: 22).

The coincidence of the double winnow/window diagram is explored here as a kind of guiding figure (or "interpretive filter") for engaging with the intermingled nature of contemporary teletechnologies - one which draws from both the Derridean and Ulmerian iterations of the choral diagram. This engagement with teletechnologies via the overlayed double winnow/window diagram follows Ulmer's notion of electronic writing insofar as it is more concerned with discovery than proof. That is to say, it is prospective, in the sense of mining or prospecting, an opening up to speculation of various "veins" (within the lode that constitutes the whole apparatus of teletechnology in general) in order to see what they might yield and where they might lead.

Yet I hesitate to describe the discovery of this coincidence, as Ulmer might, as a "Eureka moment." Rather, it is a coincidence that is resisted due to a fear that in aligning the Windows icon (which stands as a kind of metonym not just for Bill Gates and Microsoft and all that both might represent, but for globalised telecommunications and media production in general) with the choral grid (which in a similar way might stand, metonymically, for the philosophy of Jacques Derrida) there is a risk, through this surface alignment, of merely perpetrating yet another form of violence against Derrida and the intricacies of his thought (not to mention against Ulmer and his thought).

However, despite such an unlikely convergence, such apprehension, it would seem, need not be restrictive. It is Derrida who in fact writes that 'interesting coincidences are necessary coincidences' (Derrida, 1987: 171).As Ulmer puts it, "Chora is about the crossing of chance and necessity, whose nature may be discerned only indirectly in the names [and I would add, the ideas and associations] generated by a puncept rather than as a concept (or paradigm) [....]" (2001: 332).

Coincidence must be loved, received, treated in a certain way. The question is, in which way? Coincidence must be respected, though it is not easy. Such respect demands an orientation, a disposition and exercise to respect the important aspects of the coincidence. (Derrida, 1987:172)

In the present context, then, what might this disposition be? The following preliminary observations provide a useful initial point of orientation and departure from which to exercise and respect the important aspects of the chorographical coincidence suggested in the above diagram (and in/by diagrammatology). The etymology of diagram (di/a + gram) reveals something of the potential that diagrammatology and the above double winnow/window diagram hold for negotiating binary thinking and for critically engaging with the contemporary apparatus of teletechnologies. According to one possible derivation of the word diagram, di- is from the Greek dis-, meaning 'twice, two, double'. And according to a second, more common etymological formation, dia- means 'through', and -gram, from grapho, means 'to write', and 'denotes a thing written or recorded, often in a certain way' (diagrammatically, for example). Thus, diagrammatology permits the possibility of thinking through the double (di). That is to say, it is through writing (dia+gram) that one is able to think through binaries, in both senses of the word through: as a way of simultaneously working with and against binary oppositions, of 'undoing-preserving' opposites as Spivak puts it (Spivak, 1997: xliii).Part-and-parcel of this process of 'undo-preserving' opposites is remembering, as Meaghan Morris remarks, that 'binarization, too, has differing aspects:' 'not all binarized terms are opposed terms (the drawing of a distinction is not necessarily oppositional), and oppositions can be alternating, or 'only relative' [...], as well as rigidly divisive; no positioning of a term is final, and 'nonsymmetrical' reversals are always possible between terms [...]' (Morris, 1996: 393). It is this very act of 'thinking through opposites,' of 'undoing-preserving,' that I see as captured in the aforementioned chorographical coincidence of the double winnow/window.

Let us (re)turn - albeit far too briefly and only by way of outline - to the issue of the diagram, and of this particular winnow/window (filter/screen) diagram, as an abstract means for representing, thinking about and explaining the complex conditions we face, and the question of what these conditions might be.

If a name could be put to this winnow/window diagram, it might well be a double name - that which Derrida terms the 'two traits' of actuality: "artifactuality" and "actuvirtuality" (Derrida & Stiegler, 2002: 3). The coining of these two 'portmanteau nicknames' (3) is a continuation of Derrida's deep-seated interest in 'thinking through binaries' and revealing what Niall Lucy describes as 'the "aporetic" moment' or "blind spots" that structures all oppositional logic (Lucy, 2004: 1). In this particular instance, these issues are explored by Derrida around a consideration of the notion of actuality and "our experience of the present [...] as something that is produced (made, made up)" (Lucy, 2004:3). Actuality, Derrida writes, 'is not given but actively produced, sifted, invested, performatively interpreted by numerous apparatuses which are factitious or artificial, hierarchizing and selective [...]' (Derrida & Stiegler, 2002: 3). Derrida coins the term "artifactuality" to describe these processes. The second trait of "actuality" is captured in Derrida's insistence 'on a concept of virtuality (virtual image, virtual space, and so virtual event) that can doubtless no longer be opposed, in perfect philosophical serenity, to actual reality in the way that philosophers used to distinguish between power and act, dynamis and energeia,' and so forth (Derrida & Stiegler, 2002: 6). Derrida coins the term "actuvirtuality" to describe this second trait. The import of this insistence on the artifactuality/actuvirtuality of teletechnological experience is 'to let the future open' (Derrida & Stiegler, 2002: 21):

It is to show that what counts as actuality in the present can no longer be confined to the ontological opposition of the actual and the virtual, despite the ongoing necessity of this opposition to every form of politics. (Lucy, 2004: 6)

Derrida's 'thinking through' of the traditional ontological opposition of the actual and the virtual (and of the actual as the 'undeconstructible opposite of artifice and the artefact') thus holds manifold implications for media and cultural theory that extend far beyond a simple commentary on the way in which media produce rather than simply record events (Lucy, 2004: 4). This reading necessitates a responsibility to analyse the media, 'to learn how the dailies, the weeklies, the television news programs are made, and by whom' (Derrida & Stiegler, 2002: 4). A responsibility that is made all the more urgent by the fact that, in our time, 'the least acceptable thing on television, on the radio, or in the newspapers today is for intellectuals to take their time or to waste other people's time there' (Derrida & Stiegler, 2002: 6-7).

Moreover, not only does artifactuality and actuvirtuality necessitate a responsibility to analyse media, it is a responsibility that is open to the future and open to the other.

Such an understanding of the actual as what is always 'actively produced' and 'performatively interpreted' is not an excuse for disengaging from public life or for affecting a disinterest in real-historical events. If the condition of actuality is that it must be made, then it must be able to be made differently [...]. That is why it's possible to make another artefact of the other - as the arrivant, the absolute stranger. (Lucy, 2004:6)

In practical terms, Lucy suggests, 'remaining as open as possible to the radical alterity of others [...] means only that, as a place from which to start, an artefact of the other arrivant leaves open the greatest space for the possibility of a non-violent future to come' (Lucy, 2004: 6).

To return, momentarily, to the winnow/window diagram: where Derrida's choral grid serves as a diagrammatic distillation of his reading of the chora section of the Timaeus, the winnow/window (filter/screen) diagram serves as a distillation of Derrida's twin notions artifactuality and actuvirtuality. That is to say, this, the third, iteration of the choral diagram functions as a kind of prompt or reminder of the responsibility to analyse the media, and for media and cultural theorists (etc.), to remain open to the future and to the other.

Yet, the insights gained from this reading of the twin facets of actuality can be extended according to a slightly different yet complementary set of considerations. This change in direction might be summarised according to the following crude delineation. If Derrida's reading of the actual can be taken to activate (or be abstracted in) the diagram's winnowing function as a critical interpretive filter for engaging with teletechnologies, the second set of considerations are distilled in and framed by the window/screen aspect of this same diagram, and can be usefully introduced via the relay of humour.

Joke:

Q. What architectural element do Jacques Derrida and Bill Gates have a shared interest in?

A. glas/s windows.

This joke isn't very funny. The central pun in this joke certainly wasn't funny for Peter Eisenman as he reflected back on his Villette collaboration with Derrida:

Jacques, you ask me about the supplement and the essential in my work. You crystallize these questions in the term/word/material glas/s. You glaze over the fact that your conceptual play with the multifaceted term glas is not simply translatable into architectural glass. One understands that the assumption of the identity of the material glass and your ideas of glas, in their superficial resemblance of letters, is precisely the concern of literary deconstruction; but this becomes a problem when one turns to the event of building. This difference is important. For though one can conceptualize in the building material glass, it is not only as you suggest - as an absence of secrecy, as a clarity. While glass is a literal presence in architecture, it also indexes an absence, a void in a solid wall. Thus glass in architecture is traditionally said to be both presence and absence. (Eisenman, 1987:187)

While this joke was apparently no laughing matter for Eisenman, the glass window serves as a useful frame for engaging with contemporary teletechnologies and attendant issues such as presence and absence, public and private, transparency and secrecy, and so forth.

The Australian media theorist Scott McQuire places the architectural window in a broader context of a 'cultural history of transparency' (McQuire, 2003: 103-123). This context enables McQuire to 'sketch a cultural logic linking the modernist project of architectural transparency to the contemporary repositioning of the home as an interactive media centre' - charting, in other words, a 'shift from glass windows to screen walls' in both an architectural sense (as in the much-publicised Gates house), and in the rise of media phenomena such as the Big Brother television franchise (McQuire, 2003: 103,110, passim). In the case of Big Brother, what McQuire identifies in this program is a reconceptualisation of private and public space where the private is given up in the name of public entertainment (McQuire, 2003: 119). And while this transformation of the private 'may well offer a glimpse of a more open society with greater transparency in interpersonal relations,' it is suggested that 'this promise should also be seen as part of the historical process by which surveillance has been normalised in the name of minimising social risk' (McQuire, 2003: 119). McQuire posits that the popularity of programs such as Big Brother 'might be seen as the entertainment complement to other policies of "border protection" which preoccupy the contemporary nation-state swimming the tides of globalisation' (McQuire, 2003: 120). It is a particularly apposite remark given that Derrida's thinking on teletechnologies and the actual is part-and-parcel of his thinking on a broader European (and global) geopolitical context that is marked by renewed desire for the "home," in both its domestic sense and in a more threatening nationalistic sense (Derrida & Stiegler, 2002: 79-80).

This same geopolitical and global context - characterised by an overabundance of information and a growing tangle of interdependencies, according to one account (Augé, 1995: 28) - is also seen to have dramatically reconfigured the very nature of interpersonal communication through an increasingly complex interplay of presence and absence. Concomitant with and overlapping this interplay is an equally complex intermingling of public and private space and of "actual" and "virtual" space (actuvirtuality) to create a peculiar kind of paradox which the anthropologist Marc Augé characterises as the creation of an 'excess of space correlative with the shrinking of the planet' (Augé, 1995). Augé coins the term "non-places"' to describe this expanding excess. "Non-spaces" are those interstitial zones where we spend an ever-increasing proportion of our lives: in supermarkets, airports, hotels, cars, on motorways, and in front of ATMs, TVs and computers. Augé argues that a new form of anthropology - an "anthropology of supermodernity" - is required if we are to begin to account for and make sense of these teletechnological "non-places" (Augé, 1995: passim).

A key point to add to Augé's account of the non-places of supermodernity (to employ his phrase) is that computer-mediated communication and the endless flow of global informational and media vectors is a priori anchored in the flows of the everyday. The global is filtered through the local, in other words. Just as importantly, teletechnological machines, and computers in particular, are no longer stationary items; they are increasingly miniaturised and made mobile.One might say that teletechnological equipment in general, and computers in particular, are undergoing an increasing transmogrification in form and use from stationary items to stationery items: devices that are small, transportable, and often designed with aesthetics as much as function in mind. Thus, in the face of globalised communications, we cannot afford to lose sight of the reality that cyberspace temporality is experienced from the local and, increasingly, from local mobility, from our own movement in time through space, whether this be in transit (city streets, train, plane, automobile) or at any of a number of possible destinations (home, car, office, library, hotel, transit lounge). In short, and to state the deceptively simple: 'we have to relearn how to think about space' (Augé, 1995: 36). In part this requires relearning how to think about space as teletechnological space. And in light of increased technological mobility, such spatial relearning, as Augé suggests, also involves thinking about 'space as frequentation of places [and 'non-places'] rather than a place' (Augé, 1995: 85).

It could be suggested, then, that any project that attempts to rethink place and teletechnology in these terms, to following Augé's lead, needs to pay attention to 'factors of singularity:'

singularity of objects, of groups or memberships, the reconstruction of places; the singularities of all sorts that constitute a paradoxical counterpoint to the procedures of interrelation, acceleration and delocalization [and I would add relocalisation] sometimes carelessly reduced and summarized in expressions like 'homogenization of culture' or 'world culture'. (Augé, 1995: 39-40)

In the context of the above discussion of the actual and the virtual, inside/outside, and the question of the other, it is noteworthy that, for Augé, within 'the contemporary world [...] with its accelerated transformations' there is 'a renewed methodical reflection on the category of otherness' (Augé, 1995: 24).

A great deal more could be said here about the window and interface culture. However, I will limit myself to the following concluding remarks, which concern a past thread in the Association of Internet Researchers (AoIR) email list where many of the above issues resurface. At the time, this thread generated considerable debate and a flurry of postings. It developed from an initial questioning of the suitability of drawing on notions of space and place and other like metaphors when writing about the Internet and related technologies. An early posting in this exchange declared a determined resistance to the continued use of the term space in such research:

I believe that the employment of such terms as 'space' and 'cyberspace' in popular and academic writings about the computer and Internet technologies makes it seem like representations are a kind of material environment. This writing repeats and even enhances design strategies that describe synchronous settings as 'rooms', Internet maps that produce unnecessary and fictive geographies, and programming that makes users' progression through sites seem like bodily movement. Such visceral renderings discourage critical interventions into Internet representations because sites seem tangible. The conflation of space-producing discourses with user investment in particular sites and identities threatens to make stereotypes 'real.' The represented bodies of Internet settings are 'fleshed out' because there seems to be an environment that can support varied bodily processes. Computer representations can also justify the perpetuation of physical but certainly not necessary or natural conditions by mirroring material circumstances. (White, 2004)

The post concludes with the qualifier: 'I also continue to ponder other ways that we can write about and experience technologies' (White, 2004). In response to this parting remark, another contributor wonders whether the above poster, or others on the list, has 'an alternative suggestion [that might be offered] constructively in addition to pointing out flaws of the space and place metaphors?' (Bunz, 2004) Alternatives were not forthcoming; one suggestion eventually put forward is the somewhat prosaic and alternative term "setting."

What seems to be played out in the AoIR debate bears certain, albeit qualified, resemblances to the difficulties facing Derrida and Eisenman, and Ulmer after them: the difficulty of representing the unrepresentable. Which is to say, this same problematic also characterises much contemporary (and past) discourse on teletechnologies and "cyberspace:" a kind of ceaseless straining to come to terms with, to define and delimit that which, through its intermingled character and diffusion, increasingly evades simple conception and strict definition. Further complicating this already complicated scene is the fact that what arguably lies at the heart of the AoIR place/space debate are equally fraught considerations of (and attempts to represent) vexed issues such as subjectivity, (dis)embodiment, and otherness, to name a few.

It is in this context, for this reason, that it would be interesting to posit khōra as a further alternative (or supplement) to space/place/setting. Of course, there is merit in proposing this alternative (or supplementary) term, but, as Derrida might suggest, writing "sous rature" ("under erasure"), rendering the word in strikethrough font - khōra - in order to highlight its status as provisional, inadequate. Redeployed in this way, khōra is useful insofar as it stands as one name that can be given to that which is unnameable. It also sheds light on the ongoing struggle to come to terms with the issue of subjectivity and the category of the other, both of which underpin so much of computer-mediated communications research. Some of this illuminating potential is discernible in the following summary of Derrida's thinking on khōra:

as Derrida sees it [...] khora is that third thing (between the intelligible and the sensible) that makes it possible to think anything like the difference between pure being and pure nothingness (or between my autonomous selfhood and your autonomous otherness); it is what makes it possible to think the difference between 'I' and 'you.' (Lucy, 2004: 68)

And while Ulmer clearly develops the notion of khōra in different directions to what is suggested in the above passage, his understanding of chorography nonetheless makes for an important additional layer here. 'Chora evokes electronic media,' he writes, it 'concerns not this or that machine, not a winnowing basket or a convex mirror, not a computer monitor, but machinery or technology as such' (Ulmer, 1994: 69, emphasis added). That is to say, as another term for heuretics, or the logic of invention, Ulmer's understanding of khōra brings to mind both the notion of poesis as revealing or making in general (such as Heidegger develops it in 'The Question Concerning Technology' and elsewhere), as well as Donald Theall's conception of 'the poetic' as an organising term for all forms of 'inventive cultural productions' (Theall, 1995: xiii).

Thus, if the operation of the diagram, its function, is to suggest, as Deleuze claims, hopefully what might be suggested by the above winnow/window diagram is a prompt in a double sense. It operates as a mnemonic (or mnemotechnical) device: a reminder of the intermingled and ambivalent nature of the actual and the virtual, and of the responsibility to analyse what Derrida calls the whole apparatus of teletechnology in general. (Derrida & Stiegler, 2002) And, at the same time, it serves as a reminder or prompt 'to let the future open,' to engage with the 'possible impossible' of invention: an encouragement to invent, to act, and to invent new actualities which remain as open as possible to the radical alterity of others.

References

ANY ('Diagram Work' special issue, eds Ben van Berkel and Caroline Bos), 23 (1998).

Augé, Marc. Non-Places: Introduction to an Anthropology of Supermodernity, trans. John Howe (London & New York: Verso, 1995).

Bennington, Geoffrey, and Jacques Derrida. Jacques Derrida, trans. Geoffrey Bennington (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1993).

Bunz, Ulla. 'Re: first post (An Internet without Space)', posting to air-l@aoir.org mailing list, 3 February (2004).

Confurius, Gerrit. 'Editorial', Daidalos, 74 (October, 2000): 4-5.

Daidalos ('Diagrammania' special issue, ed. Gerrit Confurius), 74 (October, 2000).

Deleuze, Gilles. 'The Diagram,' in Constantin V. Boundas (ed.) The Deleuze Reader, trans. Constantin V. Boundas (New York: Columbia University Press, 1993), 193-200.

Derrida, Jacques. 'Letter to Peter Eisenman,' in Jeffrey Kipnis and Thomas Leeser (eds) Chora L Works: Jacques Derrida and Peter Eisenman (New York: The Monacelli Press, 1987), 182-185.

---. 'Why Peter Eisenman Writes Such Good Books,' in Jeffrey Kipnis and Thomas Leeser (eds) Chora L Works: Jacques Derrida and Peter Eisenman (New York: The Monacelli Press, 1987), 95-101.

---. 'Psyche: Inventions of the Other,' trans. Catherine Porter in Lindsay Waters and Wlad Godzich (eds) Reading de Man Reading (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1989), 25-65.

---. 'khōra,' trans. Ian McLeod in Jacques Derrida, On the Name edited by Thomas Dutoit (Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 1995), 89-127.

Derrida, Jacques, Eisenman, Peter and Kipnis, Jeffrey. 'Transcript Seven,' in Jeffrey Kipnis and Thomas Leeser (eds) Chora L Works: Jacques Derrida and Peter Eisenman (New York: The Monacelli Press, 1987), 104-112.

Derrida, Jacques, Eisenman, Peter and Kipnis, Jeffrey. 'Transcript One,' in Jeffrey Kipnis and Thomas Leeser (eds) Chora L Works: Jacques Derrida and Peter Eisenman (New York: The Monacelli Press, 1987), 7-13.

Derrida, Jacques, and Kipnis, Jeffrey. 'Afterword,' in Jeffrey Kipnis and Thomas Leeser (eds) Chora L Works: Jacques Derrida and Peter Eisenman (New York: The Monacelli Press, 1987), 166-172.

Derrida, Jacques, and Stiegler, Bernard. Echographies of Television: Filmed Interviews, trans. Jennifer Bajorek (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2002).

Eisenman, Peter. 'Post/el Cards: A Reply to Jacques Derrida,' in Jeffrey Kipnis and Thomas Leeser (eds) Chora L Works: Jacques Derrida and Peter Eisenman (New York: The Monacelli Press, 1987), 187-189.

---. 'Separate Tricks', in Jeffrey Kipnis and Thomas Leeser (eds) Chora L Works: Jacques Derrida and Peter Eisenman (New York: The Monacelli Press, 1987), 132-136.

---. Diagram Diaries (London: Thames and Hudson, 1999).

Kipnis, Jeffrey, 'Twisting the Separatrix,' in Jeffrey Kipnis and Thomas Leeser (eds) Chora L Works: Jacques Derrida and Peter Eisenman (New York: The Monacelli Press, 1987), 137-160.

Kipnis, Jeffrey, and Leeser, Thomas (eds). Chora L Works: Jacques Derrida and Peter Eisenman (New York: The Monacelli Press, 1987).

Lobsinger, Mary Lou. 'Cedric Price: An Architecture of the Performance,' Daidalos, 74 (October 2000): 22-29.

Lucy, Niall. Beyond Semiotics: Text, Culture and Technology (London and New York: Continuum, 2001).

---. A Derrida Dictionary (Oxford: Blackwell, 2004).

McQuire, Scott. 'From Glass Architecture to Big Brother: Scenes from a Cultural History of Transparency,' Cultural Studies Review 9(1) (May, 2003): 103-123.

Mitchell, W. J. T. 'Diagrammatology,' Critical Inquiry, Spring (1981): 622-633.

Morris, Meaghan. 'Crazy Talk Is Not Enough,' Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 14 (1996): 384-394.

Speaks, Michael. 'It's Out There... The Formal Limits of The American Avant-Garde,' in Stephen Perrella (ed.) 'Architectural Design Profile, No. 133: "Hypersurface Architecture,"' in Architectural Design, 68 (5-6) (London: Academy Editions, 1998): 26-31.

Spivak, Gayatri Chakravorty. 'Translator's Preface', in Jacques Derrida Of Grammatology trans. Gayatri Spivak corrected edition (Baltimore and London: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1997), ix-lxxxvii.

Theall, Donald. Beyond the Word: Reconstructing Sense in the Joyce Era of Technology, Culture and Communication (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1995).

Tofts, Darren. 'Fuzzy Culture,' 21•C, 25 (1997): 32-36.

---. '→↑→: 'Diacritics for Local Consumption', Meanjin, 2 (2001): 102-114.

Tofts, Darren, and McKeich, Murray. Memory Trade: A Prehistory of Cyberculture (North Ryde, NSW: 21•C/Interface, 1998).

Tschumi, Bernard. Cinégramme Folie: Le Parc de la Villette (Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton Architectural Press, 1987).

Ulmer, Gregory L. Teletheory: Grammatology in the Age of Video (New York and London: Routledge, 1989).

---. Heuretics: The Logic of Invention (Baltimore and London: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1994).

---. 'Traffic of the Spheres: Prototype for a ME-morial,' in Mikita Brottman (ed.) Car Crash Culture (New York: Palgrave, 2001), 327-343.

White, Michele. 'Re: first post (An Internet without Space),' posting to air-l@aoir.org mailing list, 3 February (2004).