Digital Manipulability and Digital Literature

Serge Bouchardon and Davin Heckman put the digit back into the digital by emphasizing touch and manipulation as basic to in digital literature. The digital literary work unites figure, grasp, and memory. Bouchardon and Heckman show that digital literature employs a rhetoric of grasping. It figures interaction and cognition through touch and manipulation. For Bouchardon and Heckman, figure and grasp lead to problems of memory - how do we archive touch and manipulation? - requiring renewed efforts on the part of digital literary writers and scholars.

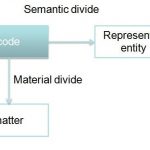

Introduction On a theoretical level, the Digital is based on the manipulation of discrete units with formal rules (Bachimont). On an applicative level, interactive works are based on the gestural manipulations of semiotic forms (text, image, sound, video) by the reader. Both types of manipulations mentioned above are related. Manipulation is indeed the essence of the Digital. In terms of manipulation, the Digital offers a range of technical possibilities. To what extent can these possibilities affect the conditions and modalities of literary writing? The idea here is to confront literary creativity with the manipulative possibilities of the Digital. To what extent can digital literary writing, in turn, affect the broader analytic landscape? The idea here is to open calculate language to creative possibility, and thus explore its liberatory political potential. There seems to be a mutual incompatibility between the Digital and the Literary. Whereas literary expression (and artistic expression more largely speaking) mobilizes a material and gives it meaning, the Digital has to discard the meaning of writing in order to make it calculable and manipulable, as the history of the Digital shows. Despite this significant difference, authors have been creating literary works on computers for over thirty years. These works are sometimes called digital literature, electronic literature, e-literature, or cyberliterature. A work of digital literature is a piece created with a computer and meant to be performed on a computer (Hayles 1-42). A distinction ought to be made between digitized works and digital works. A digitized work is a work conceived for another medium (the printed medium for example), but made accessible on a digital medium. A digital work is a work specifically created for the computer and the digital medium and it exploits some of their characteristics: hypertext technology, multimedia, interactivity. There is a great diversity amongst works of digital literature, including: hypermedia, kinetic, generative, and collective pieces. The mutual resistance between the Digital and the Literary, which first creates a tension, is at the same time that which makes invests it with potential: on an aesthetic level of course, but also on an epistemological one. As a matter of fact, the tension between digital manipulability and literary creation leads us to reexamine certain notions, chief among them are the logocentrism which has crept into contemporary understandings of representation (as exemplified by the rise of religious fundamentalism under late capitalism) and the hyperelativism which fractures binding social consensus (as exemplified by the decline of the public across the same period). In this paper, we will focus on three notions in particular which are revalued and reconfigured by the relationship between digital manipulation and literary writing: the notions of figure, of grasp and of memory. These notions intervene on the three complementary levels of a digital literary work: the figure concerns the manipulation of a semiotic form, the grasp involves the manipulation of the interface, the memory concerns the manipulation of the whole creation for preservation purposes. As poiesis is defined against instrumental language, so digital literature prompts an understanding of expressive “language” and its trifold relation to subjectivity. As a heuristic, digital literature provides insights into an understanding of language within interpersonal persuasion (rhetoric via figure), shared systems of meaning (anthropology via grasp), and the technical system (archivistics, or “archival science,” via memory). In the schematic of individuation developed by Bernard Stiegler, individuation is accomplished through a triple process: the individual (or psychic), the social (or collective), and the technical (or techno-logical). Stiegler explains, “The I, as a psychic individual, can only be thought of in relationship to a we, which is a collective individual: the I is constituted in adopting a collective tradition, which it inherits, and in which a plurality of Is acknowledge each other’s existence” (2009). Thus, the formation of subjectivity is an interplay of different processes informing identity. The individual experiences him or herself in the context of others. The collective experiences itself as a group of individuals that can be offset from other groups. A conventional understanding of the process would dictate that our identity is produced by our capacity to identify with those groups to which we belong and our ability to contribute as individuals to those groups in a recognizable way. To this dual process, Stiegler adds the question of how individual and collective identifications are recorded and replayed, producing both the capacity for cultural “inheritance” and possibility of inscription (i.e. capable of making decisions, entering into epiphylogenesis, developing a temporal consciousness).Another way to think of this interplay of societies, individuals, and technics is to think of the various words with their root in the Latin legare, which gives us “legend,” “legacy,” “legitimate,” “legal,” “delegate,” “legible,” “legislate,” etc. The root word and its offspring reveal the relationship of the individual and the collective engaged in hominization. Just as print literature opened up the analytic advantages of print to creative intervention and reflection, so digital literature opens up the augmented analytic capacity of the computer age, and in doing so allows us to reexamine the characteristics of signification more broadly. Digital literature is the heuristic by which the human is experienced against the backdrop of an instrumental, logocentric regime. 1. Digital manipulability On a theoretical level, the Digital is defined as a technical device based on discretization and manipulation with formal rules. Relying on sequences of zeros and ones, the Digital is the manipulation of discrete units deprived of semantics. There is indeed a “semantic divide” [Bachimont, 2007]: the Digital doesn’t have any proper meaning or interpretation (cf. figure 1). This level is plain calculation; it is at this level that one has access to the universality of calculation and its possibilities.

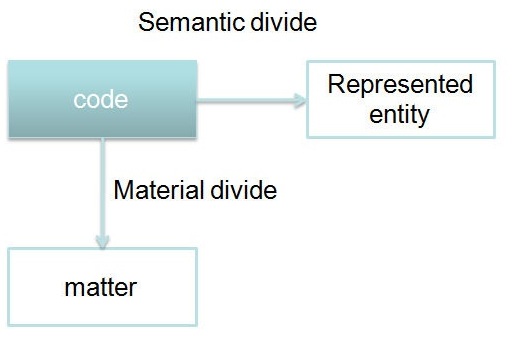

By nature, a text on a digital medium is thus the result of calculation. A digital text is made up of two types of texts: a text as a code and a text displayed on screen. I am referring here to Bruno Bachimont’s (Bachimont 2007, 23-42) distinction between recording form (“forme d’enregistrement”) and restitution form (“forme de restitution”). In a book, the recording form (the printed text) and the restitution form are identical, whereas they are distinct on a digital medium. In this medium, the source code is not what the user sees on the screen: for one form of recording, several forms of restitution are possible because of the mediation of calculation. This distinction is close to the distinction between “scripton” and “texton” by Espen Aarseth (Aarseth1997, 62); indeed, Aarseth coined these terms to distinguish between underlying code and screen display. Though the recording form and the restitution form of print are indistinct, one can perceive a relative desire for manipulability at the level of the codex, the verse, the word, and the letter. While it is critical to note the integral role of computation in the restitution of the digital text, it is difficult to dispute the embedded ideal of analytical manipulation present, for instance, in this relatively conventional scholarly format. Citations and references, arranged and controlled, performing the work of analysis in a manner that aspires towards its hypothetical restitution in the minds of others. And it would, perhaps, be a mistake to overlook the function of this ideal in the theory of a “clockwork universe,” the scientific method, the scriptural focus of the Protestant Reformation, and the general spirit of the Enlightenment. In each case, the hope is for practice of rendering and calculation that is immune to the capriciousness of the human observer, and instead reliant on a habituated form of reading and rational thought that can be externalized and re-membered. As an interesting digression, the early work of literary scholarship was primarily geared towards a kind of bibliography, history, and translation, with the emphasis placed on correcting and preserving the record. What we understand as literature today was an insurgent exploitation of the analytic liabilities of print media, an entertaining distraction of the emerging middle class, a prototypical form of hacking and gaming that had found its moment of opportunity between the priorities of Enlightenment humanism and Protestant faith. It is only later when literary art became important from an expressive, interpretive, and cultural perspective, that literary scholars were able to successfully incorporate many of the features literature had initially resisted (stasis, linearity, clarity, universality, and, eventually, under the New Critics, Truth) into its central value. Literature’s place is that of a niche organism, between the feeling and reason, and thus the medium of archived speech lends itself to both passionate assertions of belief and falsifiable demonstrations of reason, both considered species of truth with ontological implications. On the line is the long term accountability of the subject. Today, literature is held up against digital culture for its ability to habituate readers into linear thought, reasoned discourse, and deep concentration. And, of course, as textual writing, it is often very good at these things. But what is often lacking from this understanding is critical context as a form which exposes the limitations of its proto-digital ancestor (i.e. the word as Truth). In a world where heavy analytical tasks are performed by computers and policy decisions are removed democratic process, such a context is increasingly meaningless. Without the lively explorations of the limits of inscription and their competing priorities for truth, faith becomes fickle and facts become flexible. In other words, the basic processes that literature mediates become deprived of their foundations as an affective force. The strongest evidence of this shifting foundation is, perhaps, the preponderance of conspiracy theories, within articulations of faith and reason, as all-consuming, teleological truths so true they must not represented — speculative “non-fictions” predicated on the idea that, to quote the X-Files slogan, “The Truth is Out There.” But it tends not to be held, but to be discovered. Truth tends not to be linear and centralized, but distributed within the unofficial and official records. It tends not to be directly represented, but symbolized through occult references. Thus the plain-spoken democratic spirituality and the egalitarian discourse of rational thought are replaced with calculated interpretations of modular texts. Still, calculation is always present between a recording form and a restitution**form. That we forget this is a convenient nostalgia that reifies both the “chaotic” complexity that the machine can comprehend and the “stable” simplicity of a bygone era. Between these two extremes, we lose sight of the human capacity to modify and adapt to conditions, to act. While the raison d’être of paper documents is that they make the graphic and spatial representation of information possible (Goody 1977, 140-196), the raison d’être of digital documents is that they make calculation on these documents possible. As a matter of fact, it is because calculation allows inscriptions to be manipulated that the reader can be given the possibility to manipulate inscriptions. Thus the essence of the digital could be manipulability (Ghitalla & Boullier 2004, 19-125). The digital text is as much a manipulable text as a readable text, and for this reason, the reader’s reception of a text may have to be revalued. 2. Figures of gestural manipulation Literary and artistic digital creations often rely on gestural manipulations from the reader (for instance to activate a link, to move an element on screen, to enter text with the keyboard). In an interactive work, the gesture acquires a particular role, and fully contributes to the construction of meaning. Y. Jeanneret reminds us that turning a page “doesn’t involve any particular interpretation of the text” (Jeanneret, 2000, 113); on the contrary, in an interactive work, “clicking on a hyperword or an icon is itself an interpretative act. The interactive gesture is primarily the actualization of an interpretation through a gesture.” To what extent can these gestural manipulations contribute to the constitution of rhetorical figures? Since Antiquity, the figures have made up a significant part of rhetoric, even though rhetoric should not be reduced to rhetorical figures. Figures are generally divided into four main categories: diction (e.g. anagram and alliteration), construction (e.g. chiasmus and anacoluthon), meaning (tropes, e.g. metaphor and metonymy), and thought (e.g. hyperbole and irony). The rhetorical figure is traditionally defined as a “reasoned change of meaning or of language vis-a-vis the ordinary and simple manner of expressing oneself.”Quintilian, De institutione oratoria, IX, 1, 11-13. In computing contexts, our understanding of the figural is influenced the divergence between the restituted figure and its recorded form as code. In the context of programming ontology, this means that objects are defined as discrete entities within the program framework. Following the arguments of the Object Oriented Ontologists, the concept of the “figure” is no longer a “figure of speech,” rather such figures are individuated precisely through their objective existence. As Levi Bryant explains, “To be is a simple binary, isofar as something either is or is not. If something makes a difference then it is, full stop. And there is no being to which all other beings are necessarily related” (Bryant 2011, 268). This flat understanding of being, without recourse to its collapse, deconstruction, or migration, is more than merely rhetorical in the context of the digital, as the chief function of the digital is, following Manovich’s identification of the database as the defining metaphor, powered by its ability to define and manipulate discrete objects. However, the functional ideal of the modular component has always had a home in machinic contexts and in the imagination. Predictably, this modularity has also been anticipated by a host of rhetorical manipulations that undermine the discrete character of the modular through literary practice. Interactive and multimedia writing calls upon certain existing figures, such as the metaphor and the metonymy. For instance, Stuart Moulthrop (Moulthrop 1991, 119-132) and Jean Clément (Clément 1994) highlighted the way in which certain figures could be reinvested in hypertextual writing. Thus Clément reckons that, because a hypertextual fragment can be understood differently depending on the reader’s journey, it calls into play the concept of metaphor (Clément 1995). Yet the figure can function somehow differently in digital literary works. In a previous paper (Bouchardon 2002, 65-86) on the digital fiction NON-roman,Boutiny Lucie (de), NON-roman, 1997-2000, http://www.synesthesie.com/boutiny/ Bouchardon showed how hypertextual navigation materializes certain rhetorical figures. In this work, the materialization of figures is rendered through the creative use of frames and windows. Bouchardon analyzed several examples, including synecdoche. Synecdoche is a figure where a part of something is used to refer to the whole thing. In NON-roman, when the reader clicks on the link “Apt. 3rd floor,” he/she triggers a materialization of the synecdoche. Indeed as he/she clicks, a window appears on the screen, offering a tour of the whole apartment (figure 2). The rhetorical figure is paired with the material space and architecture of the narrative.

Besides, in digital works, the reader has to make an action (roll over, drag and drop, type letters). This manipulation of media (text, image, video) contributes to the construction of meaning. For instance, very often, when a reactive zone is moused over, a text or a picture appears. It disappears as soon as the cursor leaves the reactive zone. This appearance/disappearance effect is here the result of the user’s action. It is exploited in many digital works. However it only becomes a figure when it provides another realm of possibility for a text, a picture, a video, giving the impression that there is depth lying under the digital surface, depth that can be explored (Bouchardon 2008). The appearance /disappearance figure can unveil the other side of things (a hidden reality). It can also suggest semantic depth, a double meaning, that objective rendering can collapse into depth and polysemy. Therefore, we can identify rhetorical figures specific to interactive writing: figures of manipulation (meaning gestural manipulation). This is a category on its own, along with figures of diction, construction, meaning and thought. The figures of manipulation are based on the user’s interaction with the interface. Let us take an example. AnonymesAnonymes.net, 2001, http://www.anonymes.net/anonymes.htmlis an online creation in French (figure 3). In the first scene, the reader is asked for his/her name, but the letters keyed in do not stay in the text area and fly away. Like the man who appears in the video loop in the background and who avoids the camera, the reader will always remain anonymous. It is a figure insofar as there is a discrepancy between the reader’s expectations and the result of the manipulation. Thus, such works highlight the potential estrangement between the aggressively asserted agency promised by the digital and the limitations of the ontological constraints they impose upon the domain of meaning to secure their smooth function.

The expression “rhetoric of manipulation” (Bouchardon 2008) seems adequate to define interactive writing. Interactive writing is based on figures of manipulation (meaning gestural manipulation), rather than on figures of meaning like tropes. Examples of digital literature show us that the notion of figure can take into account the gesture of the reader. It may modify our approach to the notion of figure in rhetorics. 3. From control to loss of grasp As seen previously, the figures of manipulation are based on the control of certain elements by the user. In The Language of New Media (Manovich 62-115), Lev Manovich analyses the influence pre-existing cultural traditions (the printed word, the cinema, and the human-computer interface) play on digital language (and on what he calls “cultural interfaces”). While the audiovisual (cinema) tradition refers to a way of controlling the flux, the human-computer interface (the control panel) refers to the idea of control by the user. Likewise, in software ergonomics, we can find complementarity between “guidance” and “explicit control” (Bastien & Scapin 1993). Control of the user and control by the user are not only intimately linked, but their inter-relations seem to be a specific mode of writing in digital works. Their constant co-presence results in a tension that produces interactivity. However, this very idea of tension is an answer to one question only: who/what manipulates? The user or the technical system? This level is that of a classical human-machine interface approach. In fact, even this question remains within an ergonomic approach while one should also consider an anthropological one. So the question is to know how the world of the user (or the supposed worlds of the user) is or is not taken into account. Francis Chateauraynaud (Chateauraynaud 1995, 236-253) suggests a model of “grasp.” According to the author, one summons two kinds of elements to have a grasp on one’s environment: elements based on conventions and material elements to be found in the immediate environment. These dual elements characterize the concept of grasp. Grasp emerges from the meeting between markers (points of reference which depend on conventions), and habits (which are localized practices). Giving control to the user does not necessarily entail giving him grasp in a traditional anthropological meaning: the user doesn’t always have the frame necessary for the grasp. At that point one sees two positions for the user :

- in control / under control;

- with grasp / without grasp.

Conversely, the user can have less control and paradoxically more grasp. Instead of thinking in terms of the user being in or under control, one should think of the user having or not having grasp. Or rather it is a question of identifying the various possible combinations. Indeed, the user can be in control and either with or without grasp, just as the user can be under control and either with or without grasp. In contrast to the discrete, objective interest of the figurative, grasp presents a subject-object orientation to our understanding of the digital. Where the figural tends to struggle with subjectivity in discrete, objective, individual terms, grasp defines subjectivity as relation. The most basic understanding of this is in the material elements of grasp: i.e. the user is the one who manipulates the tool. This is the foundation of subject-object relations and informs our understanding of prosthesis. A more loaded question becomes the conventional elements of grasp, specifically as expressed through the politics of access and influence: i.e. what is a tool and who uses it? It is along these lines that control and grasp are synchronous or divergent. What forms the subjectivity in these situations is no longer the empirical status of the figure, instead it is the place of this figure within a network of activity. For instance, on the web, full screen display and disactivation of the browser’s functionalities is an example of control by the system and of loss of grasp for the user. The user loses the points of reference of the browser’s interface. Now, preselected temporality,Let us compare the various ways of playing the time according to media. The audiovisual media are very controlling : the duration of a film coincides with the viewer’s flow of consciousness. On the contrary, the printed text is far less controlling: readers read texts at their own pace. With the digital medium, no preset pace is imposed to the user: the pace depends on the degree of interactivity present in the work. The user is alternatively controlling or controlled. which is a form of control by the system, is also a possible grasp for the user. Indeed, the user finds himself/herself in a frame which he/she is accustomed to, that of the time flux to be found in audio-visual type works. This is the case in the cinematic works – often developed with the Flash software – which are played without any interaction opportunity for the user. For instance, in My Google Body,Dalmon Gérard, My google body, 2004, http://www.neogejo.com/googlebody/ a human body is represented through pictures corresponding to the various parts of the body, with the pictures being renewed at regular intervals. The program displays the results of the requests made automatically to Google Images concerning the word “head,” “body,” “arm,” “hand,” “leg,” and “foot.” This work shows a graphic body in continuous and regular evolution.

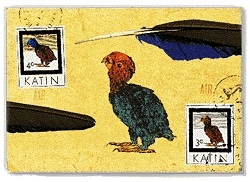

Just as interactive works rely on this constant play between a controlling and a controlled approach, they also rely on grasp and loss of grasp. The idea is to get the user involved and to destabilize him/her, so that he/she might possibly enjoy becoming disoriented and playing with the work. Thus, very often, the play between grasp and loss of grasp is the basis of literary interactive works. Ceremony of innocenceMayhew Alex, Ceremony of innocence, CD-Rom, Real World et Ubisoft, 1997.is a work made up of a succession of postcards from a painter and one of his admirers. Each postcard is an enigma that the user has to solve by doing certain things in a predefined order. Let us take the example of the first postcard (cf. figure 5): after a while, the bird shown on the picture eats the cursor of the mouse. Immediately, the cursor disappears from the screen. At that point, one may think that the user is totally under control, since he/she cannot use the mouse in the way he/she is used to. Yet, moving the mouse (whose cursor is invisible on the screen) still has an impact on the elements of the postcard. The functionality of the mouse is in fact not disactivated. One can observe an act of playing with the loss of grasp. By losing the cursor of the mouse, the user has also lost the grasp which is a point of reference for him/her. Yet the user can now achieve the task expected from him/her. The card turns round finally and the text is read by the character who wrote the message.

As in Ceremony of innocence, numerous works exploit this strategy of the loss of grasp. Figures of manipulation could be expected to give more control to the user, but in many digital literary works, the artists use these very figures to introduce a loss of grasp. When manipulating, the user finds himself/herself being manipulated by the author. This play on the loss of grasp invites the user to have a reflexive attitude towards his/her interactive practice. The rhetoric of interactive writing is an invitation to interact differently, to have another apprehension of interactivity. In digital literary works, interactivity doesn’t consist in giving more or less control to the reader, but more or less grasp. The focus on these works shows that the anthropological notion of grasp is valuable to analyze and understand interactive manipulations. 4. From stored memory to reinvented memory The tension between digital manipulability and literary creative practice led us to reexamine the notions of figure or grasp. This tension also questions the notion of memory in archivistics, the technical occasion of subjective formation. With regards to the trifold model of identity formation offered in the introduction, the question of memory takes on a special significance with regards to what Stiegler refers to as “tertiary memory,” or the various techniques and technologies for storage and transmission. As Stiegler notes, there is a tendency to overlook the technical aspect of human existence, creating a false equivalence between the computer memory and the human brain, when the more apt comparison would best understand digital storage within the context of tertiary retentions. Stiegler explains,

For 15 years now I have taken pains to show that given the fact that the computer has not been analysed or even seen as a technical prosthesis by cognitivist theory, which, in a diametrically opposed view, refers to Turing in order to define it metaphysically as an “abstract machine,” what has in fact been neglected and repressed by cognitivism, as well as by philosophy as a whole, going back to Plato’s first gesture of thought, is the place of technics in general in life, technics as the condition of life that knows… The brain is not an abstract machine, on the one hand because “abstract machines” do not exist, and on the other, because this organ is in no respect a machine: a machine is not a living organism, and therein lies its force. The brain is a living memory — that is to say a fallible memory, in a permanent process of destruction, constantly under the sway of what I call retentional finitude. This biological living memory is, however, only one memory among others: particularly alive, it is nevertheless nothing outside its inert memories — i.e., its technical memories: the essential point being the relation between what is living in the brain and what is dead in its technics qua memories. (2009)

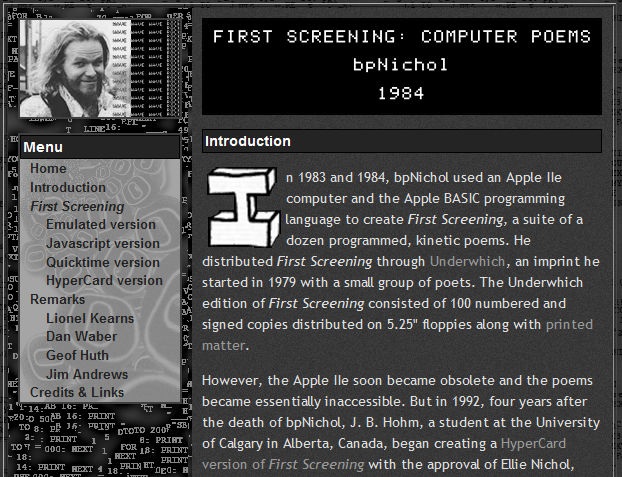

Indeed preserving a whole digital creation means preserving the ability to manipulate it, not simply for the sake of storing data, but in order to reinvent it, to read it. The archiving and preservation of digital data appear particularly crucial in the field of digital literature. The preservation of works of digital literature leads to a real theoretical and practical problem. A digital literary work is indeed not an object, but, in most cases, it is also not a simple event limited in time, like a performance or a digital installation. In fact, it partakes of both aspects: it is a transmittable object but also fundamentally a process that can only exist in an actualisation. Some authors consider that their works – notably online works – are not meant to last forever. They consider that their works bear their own disappearance within themselves. Their lability is part of the artistic project. This claim can be made a posteriori, as in the case of Talan Memmott and his Lexia to Perplexia.http://www.uiowa.edu/~iareview/tirweb/hypermedia/talan\_memmott/But the majority of the works do not claim to adhere to this aesthetics of dereliction or disappearance. What should be preserved in such digital literary works? The mere preservation of the original file seems insufficient to preserve the work. Especially so if the work is generative or interactive. In this case, the file is not the work as it is not what the reader perceives. Not to mention that online works sometimes rely on readers’ contributions: they grow thanks to the internet users’ contributions and are in a process of constant evolution. In this way, digital literature as print literature did before, opens up the analytic pretensions of contemporary writing technologies to reflection and scrutiny. Here, the ideal of the perfect thinking machine as the abstract and infinite retention machine is challenged by pleasure of works that we can change individually or socially. All the same, however, these works are not necessarily doomed to be lost to history. That the readings they inspire would activate audiences to preserve these works mirrors the archival efforts of libraries past. Though the possibility of automated duplication of everything is real and increasingly likely, within this sea of everything, the human process of reading and archiving is still active, though not necessarily so limited by material accident as print archives are with regards to shelf space, budgets, staff, and patronage. Instead, the questions of preservation and archiving revolve around programming, compatibility, bibliography, and interest. To meet the needs of such an inventory of works, the NT2 laboratory (New Technologies New Textualities, UQAM University in Montreal) constituted an online “directory of hypermediatic literature and arts.”This directory in French identifies and indexes the artistic and literary experiments on the Web, in order to describe them and to encourage their study: http://www.labo-nt2.uqam.ca/observatoire/repertoire The Electronic Literature Organizationhttp://eliterature.org/ also wishes to emphasize an editorial and reviewing activity. The ELO website indeed provides the reader with a directory (Electronic Literature Directory) selected by an “editorial collective.” ELMCIP has implemented the Knowledge Base, which documents individual works within the larger field of practice, and includes data regarding exhibitions, publications, events, courses, institutions, conferences. These three directories (in the context of an emerging network that includes Hermeneia, Po.ex, Media Upheavals, Brown Digital Repository, Creative Nation, and electronic book review) tend to contextualise the works by offering a critical documentation, but do not aim at preserving them.However, the ELO Preservation, Archiving, and Dissemination (PAD) project materialized in two DVDs, Electronic Literature Collection volume 1 and 2. The ELD has an on-going agreement with Archive-it.org (a partnership between the Internet Archive and the Library of Congress) to archive a selection of key works. ELMCIP has announced the development of its own anthology of European Electronic Literature. When dealing with the preservation of digital works, one must take into consideration the fact that digitalization does not preserve the content, but the resources and tools used to rebuild the content. Content is only accessible through the functionalities of the tools. The first consequence is that interpretation is conditioned by access tools. The second consequence is that reconstruction is variable. One can observe a proliferation of variants. Numerous versions of a similar content are to be found. Therefore, the questions which must be asked are: what makes the identity of a content? What makes some versions acceptable? What permits differentiating a variant from the original? Maria Engberg (Engberg, 2005) bore such questions in mind when she analyzed the various versions of RiverIslandCayley John, RiverIsland, http://homepage.mac.com/shadoof/net/in/riverisland.html by John Cayley. Jim Andrew’s initiative on the webhttp://vispo.com/bp to preserve the digital poem First Screening by bpNichol (1984) combines several strategies. Thus Andrews proposes:

- the original computer program coded with Hypercard;

- the emulator of the original machine which permits to run the program today (emulation);

- a rewriting of the program in javascript to play the work on today’s machines without resorting to an emulator (migration);

- a rendering of what was seen on the screen at the time through the use of a video (simulation of the event).

By proposing these complementary approaches, Jim Andrews claims that *“the destiny of digital writing usually remains the responsibility of the digital writers themselves.”*Ibid. The authors themselves have to organize the strategies of preservation of the works. It could be relevant to notice the number of authors who, in a perspective of preservation, reinvent one of their creations several years later. This is the case in Tramway,Saemmer Alexandra, Tramway, 2003-2009, http://www.revuebleuorange.org/oeuvre/tramway an online creation by Alexandra Saemmer. The first version, in 2000, has just been reinvented by its author, taking into account and poetizing the evolution of formats and systems. These practices lead to another model of archiving but also of memory. Conservation is not a preservation of the physical integrity of the content, but a permanent reinvention of the content based on the preserved elements. The issue is to preserve an identity of the content through the transformation of its resources and the variability of its reinvented renderings. What digital literature teaches us is that preservation should adopt an organic vision of memory, that is a vision in which the content has to evolve, change, adapt to be maintained and preserved. Regarding preservation, the digital age is undoubtedly the most fragile and complex context in the history of humanity. The value-added of digital technology is thus not where one expects. The digital medium is not a natural preservation medium, but is on the contrary hell for preservation. But digital technology makes us enter another universe which is a universe of reinvented and not stored memory. From an anthropological point of view, this model of memory is more valuable and more authentic than the model of print media which is a memory of storage (the book that one stores on a bookshelf just like the memory that one would store in a case of one’s brain) and the popular conception of the brain as computer. Indeed, cognitive sciences teach us that memory does not function on the model of storage. From this point of view, digital literature can be regarded as a good laboratory to address digital preservation: it makes it possible to raise the good questions and it presents the digital age as a move from a model of stored memory to a model of reinvented memory. Conclusion It is relevant to analyze the conjunction of the digital manipulative possibilities and of the modalities of literary expression. The tension between the Digital and the Literary not only permits previous media to be reexamined (paper for instance), but it also allows several well-established notions to be revalued, i.e. to be refined (figure), expanded (grasp) or transformed (memory). This is what could be called the heuristic value of digital literature. Exploiting the heuristic value of digital literature has two consequences:

- a revaluation of key notions in certain scientific disciplines (besides the notion of figure in rhetorics, grasp in anthropology, memory in archivistics, we could mention narrative in narratology, text in linguistics and semiotics, materiality in aesthetics, literariness in literary studies… (Bouchardon, 2009);

- a revealing effect regarding digital writing.

Although the Digital offers a realm of possibility to literary creation, it also presents difficulties in terms of writing and reading, notably on three levels: intersemiotisation of media (the co-building of meaning by various media - text, image, sound and video – is more difficult to grasp), hypertext reading (hypertextual navigation contributes to disorientation and compromises the reading), and author/reader dialectics (interactive contents re-negotiate the roles of the author and the reader via the availability of reading and writing tools). Digital literary works play with these difficulties and thrive on these stakes. They emphasize the tensions and throw light on the digital writing practices. In this sense, digital literature can act as a revealer for digital writing. Works cited Aarseth 1997 Aarseth Espen, Cybertext, Perspective on Ergodic Literature, John Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, 1997. Bachimont 2007 Bachimont Bruno, Ingénierie des connaissances et des contenus. Le numérique entre ontologies et documents, Hermès, Paris, 2007. Bastien & Scapin 1993 Bastien Christian and Scapin Dominique, Ergonomic Criteria for the Evaluation of Human-Computer Interfaces, technical report n°156, INRIA, 1993. Bouchardon 2002 Bouchardon Serge, “Hypertexte et art de l’ellipse”, in Les Cahiers du numérique, La navigation, vol. 3, p.65-86, Hermes Science Publishing, Paris, 2002. Bouchardon 2008 Bouchardon Serge, “The rhetoric of interactive art works”, DIMEA 2008 Conference, ACM Proceeding Series Vol.349, 2008. http://portal.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=1413634.1413691&coll=GUIDE&dl=GUIDE&CFID=10169068&CFTOKEN=68698915 Bouchardon 2009 Bouchardon Serge, “Littérature numérique: le récit interactif”, Hermes Science Publishing, Paris, 2009. Bryant 2011 Bryant, Levi R., “The Ontic Principle: Outline of an Object-Oriented Ontology*”*, in The Speculative Turn, edited by Levi Bryant, et al., re-press, Melbourne, 2011. 261-78. Chateauraynaud 1995 Chateauraynaud Francis and Bessy Christian, Experts et faussaires. Pour une sociologie de la perception, Editions Anne-Marie Métailié, Paris,1995. Clément 1994 Clément Jean, “Afternoon, a story, du narratif au poétique dans l’œuvre hypertextuelle”, in A:\LITTÉRATURE, CIRCAV-GERICO, Roubaix, 1994. http://hypermedia.univ-paris8.fr/jean/articles/Afternoon.htm Clément 1995 Clément Jean, “L’hypertexte de fiction, naissance d’un nouveau genre ?”, in Vuillemin Alain et Lenoble Michel (eds.), Littérature et informatique: la littérature générée par ordinateur, Artois Presses Université, Arras, 1995. Engberg 2005 Engberg, Maria, “Stepping Into the River - Experiencing John Cayley’s RiverIsland”, 2005. Ghitalla & Boullier 2004 Ghitalla Franck and Boullier Dominique, L’Outre-lecture, Editions Georges Pompidou, Paris, 2004. Goody 1977 Goody Jack, The Domestication of the Savage Mind, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1977. Hayles 2008 Hayles Katherine, Digital literature: New Horizons for the Literary, University of Notre Dame, Indiana, 2008. Jeanneret 2000 Jeanneret Yves, Y a-t-il vraiment des technologies de l’information ?, Editions universitaires du Septentrion, 2000. Manovich 2001 Manovich Lev, The Language of New Media, MIT Press, Cambridge, 2001. Moulthrop 19991 Moulthrop Stuart, “Reading for the Map: Metonymy and Metaphor in the Fiction of Forking Paths”, in Hypermedia and Literary Studies, Paul Delany and George Landow (éd.), p.119-132, 1991. Stiegler 2009 Stiegler, Bernard, “Desire and Knowledge: The Dead Seize the Living”, translated by George Collins and Daniel Ross, Ars Industrialis, 2009. http://arsindustrialis.org/desire-and-knowledge-dead-seize-living

Cite this article

Bouchardon, Serge and Davin Heckman. "Digital Manipulability and Digital Literature" Electronic Book Review, 5 August 2012, https://electronicbookreview.com/publications/digital-manipulability-and-digital-literature/