Electronic Literature Experimentalism Beyond the Great Divide. A Latin American Perspective

Given the longstanding but limited readership for North American, Euro and Scandinavian e-lit, will Latin America succeed in carrying its experimental and avant-garde approaches to a general e-lit audience? Claudia Kozak's expanded keynote for the 2018 ELO conference in Montreal, titled "Mind the Gap!", explores some first forays in this direction: practices that might hearken back to Puig and Borges in print; Omar Goncedo, Eduardo Darino, Erthos Albino de Souza and Jesús Arellano in the era of mainframes; and (not least) fan fiction over pretty much the entire span of literary writing.

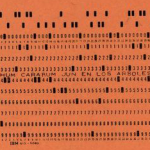

Image: Omar Gancedo, IBM (1966).

0. It may be true that contemporary digital culture is by now deeply rooted in everyday life of an important part of world’s population–including our habits of writing and reading. Yet digital literature remains more or less invisible to most people. Many people can feel “at home” within digital everyday life and, still, consider that literature is only something related to print books, at most digitized. Regarding this–at first sight–paradoxical situation, I will argue that its cause lies in the strong experimental impetus that digital literature has entailed since its first appearances in mid- 20th century. E-lit has kept this impetus up to the present; therefore, it stays under larger audiences’ radar; audiences who in general play along with mainstream digital culture. However, from my standpoint this e-lit experimentalism, which does not easily accept the whole predigested package of digital culture in its mainstream form and meaning, may also open interesting possibilities to building disruptive perceptual and cognitive experiences at a larger scale contesting hegemonic digital culture. One condition to accomplish such an endeavor, though, would be to surpass the reproduction of the–in part rejected since the sixties–“Great Divide” (Huyssen) between high and lowbrow culture or, maybe in a more accurate description of nowadays culture, between smaller but highly self-reflective audiences and broader, usually less reflective ones.

Mainstream digital culture can be certainly seen as hegemonic. Raymond Williams’ explanation of the notion of hegemony (Williams 108-114) primarily follows Gramsci’s theoretical development. Williams stresses that hegemony correlates the whole social process, that is to say, “culture” according to one of Williams’ definitions (108), with specific distributions of power and influence but not in a coercive way–which fits better to the notion of political rule or dominion. Williams, rather, regards culture as an everyday, “lived dominance and subordination of particular classes” (110), that needs constant renewal and confirmation as a “lived system of meanings–constitutive and constituting–which as they are experienced as practices appear as reciprocally confirming” (110). As discussed later, we can isolate distinctive traits that shape mainstream/hegemonic digital culture such as the alleged equivalence between technological modernization, novelty and progress; the standardization of cultural consumption concealed under algorithmic customization; the invisibility of digital materiality that poses the illusion of proximity and of equal cultural assets available for everyone.

In this essay, I will theoretically and critically explore one possible alternative scene–among others already existent or to be created. It is a scene e-lit practitioners could consider if they are inclined to breach the gap between e-lit and larger audiences, without losing the experimental emphasis that constitutes e-lit’s mark of birth and that may bring along to mainstream everyday digital culture a dose of defamiliarized perspective. Of course there would be experimental e-lit practitioners not interested in doing such a thing, similarly to other–not digital–experimental writers who do not aim to be read by larger audiences. But since e-lit shares a common ground and its mere existence with digital culture at large, I believe that it is in a good position to give other perspectives confronting mainstream/hegemonic meanings in current digital culture. And not only to just give them–as it is already doing–but to reach more people in the process.

If we are to imagine a possible–let’s hope not entirely unrealistic–scenario, I’d like to first assess experimental e-lit’s contestation of mainstream digital culture, while recuperating some established cultural genealogies such as avant-gardes and postmodernism. Afterwards, I will examine some pioneer experimental Latin American e-lit works and, subsequently, some more recent works that enact possible encounters and dis-encounters between two very different practices within online digital culture that, despite their differences, and because they turn to appropriationism (Goldsmith) as an artistic device, could establish a common ground where each one profits from the other. One of these practices is e-lit associated with conceptual and purposely uncreative writing (Goldsmith)–one of the forms literary experimentalism takes nowadays; the other is literary fanfiction that, even if it is usually only digitized–not generated using digital affordances–owes its exponential growth to virtual communities and social networks since the development of the Web 2.0.

1. In a seminal chapter on the notion of time in her book Dreamworld and Catastrophe: The Passing of Mass Utopia in East and West, Susan Buck-Morss explains avant-gardes in the context of the Russian Revolution and stresses how these artistic movements “interrupted the continuity of perceptions and estranged the familiar (…) The effect was to rupture the continuity of time, opening it up to new cognitive and sensory experiences.” (49) From my perspective, this statement also applies to other avant-garde movements at the beginning of 20th Century, namely Dada and Surrealism, which in terms of Peter Bürger’s Theory of the Avant-Garde (109) should be considered–along with Russian avant-garde after the October revolution and, to some extent, Italian Futurism and German Expressionism– as “historical avant-garde movements”, given the fact they were a specific historic response to the development or the art institution in Modernity, a response which came after the exaltation of the autonomy of art by Aestheticism. Although tracing a genealogy from experimental e-lit back to historical avant-gardes does not seem big news, it allows me to extrapolate, within certain limitations, the notion of artistic disruptions that open up new cognitive and sensory experiences, in this case, within digital culture.

When following Bürger’s argument on historical avant-gardes, we should acknowledge that the cognitive and perceptual disruptions they sought to achieve were part of an attack on the autonomy of institutionalized art in bourgeois society or, in the case of post-revolutionary Russian avant-gardes–and resuming Buck Morss’ argument–on the notion of linear progressive time that shaped social life not only in bourgeois society but also within the notion of history held by the Bolshevist party. In all these cases, the experimental disruptions implemented by historical avant-gardes were tied to the idea of a reintegration of art into a new type of life that was also inseparable from a new everyday “common” life and mass culture. The disruptions introduced by experimental e-lit might not appear with the same virulence as the attack on institutionalized art as shown, for instance, by Dada. Nonetheless e-lit has great potential to denaturalize hegemonic digital life, which is not a minor task in a world where digital culture allegedly appears as a necessary improvement of life itself.

To be clear, when speaking about mainstream/hegemonic–therefore non-critical– paths in digital culture, I am thinking of several usually intertwined aspects; namely:

a. Mainstream digital culture is an offspring of the modern worldview that presupposes an unambiguous equivalence between technological modernization, novelty and progress. This has led Western societies to a gadget culture that might slightly improve comfort but also promises instant happiness despite the fact everything usually remains in the realm of a never-ending replacement of merchandises. The foundation of this worldview is not only capitalism, but also a notion of technology merely based on instrumental criteria correlative to an alleged neutrality of data and information, as philosophies of technology have pointed out many times from numerous positions such as those advanced, for instance, by Adorno and Horkheimer (Dialectic of Enlightenment; Marcuse One-Dimensional Man) or Heidegger (“The Question on Technology”). In the last decade or so, many cultural critics–Evgeny Morozov (La locura del solucionismo tecnológico) and Éric Sadin (La humanidad aumentada; La siliconización del mundo), among others–have been “updating” this type of cultural criticism with regards to contemporary digital technology, by analyzing the never-ending happiness promised by technological gurus settled in Silicon Valley. These gurus’ current vision, anchored in notions of innovation and/or improvement, results in a sort of technocratic ideology of total algorithmic life improvement: “solutionism” in terms of Morozov or algorithmic governance within “world siliconization” in terms of Sadin. A crucial aspect of algorithmic governance, related to Big Data analytics and pattern recognition, is that it conceals under an allegedly neutral technology a highly political issue (Apprich, x). Indeed, as Apprich asks when introducing Hito Steyerl’s contribution to the essay collection Pattern Discrimination, “why is it that there is almost no discussion about the implicit racist, sexist, and classist assumptions within network analytics?” (x). We could say that, basically, this happens because our digital culture “invites” us to see data as a collection of neutral facts while, as Florian Cramer argues in his contribution to the same essay collection–also going back to the debate on the allegedly neutrality of data held by Frankfurt School–“data is always qualitative, even when its processing is quantitative: this is why algorithms and analytics discriminate, in the literal as well as in the broader sense of the word, whenever they recognize patterns.” (24-25)

b. Although in a more fluid fashion than modern mass culture, digital mainstream culture relies on the standardization of cultural consumption–from social media interpersonal behavior to, again, a more general algorithmic culture (Galloway, Gaming: Essays on Algorithmic Culture; Striphas, “Algorithmic culture”). Following Alexander Galloway, Ted Striphas defines “algorithmic culture” as “the enfolding of human thought, conduct, organization and expression into the logic of big data and large-scale computation, a move that alters how the category culture has long been practiced, experienced and understood.” We can even think of it not in terms of culture but–with Morozov–of life itself. Another contemporary critic, Taina Bucher, begins her book If … Then: Algorithmic Power and Politics with “the premise that life is not merely infused with media but increasingly takes place in and through an algorithmic media landscape (…) Social media and other commercial Web companies recommend, suggest, and provide users with what their algorithms have predicted to be the most relevant, hot, or interesting news, books, or movies to watch, buy and consume.” (1). Moreover, the illusion of freer consumption is paradoxically accomplished by targeting audiences in a customized way, algorithmically oriented by segmented profiles.

c. Algorithmic life is also related to techno-vigilance as a huge and usually unnoticed social control device (Bruno, Máquinas de ver, modos de ser). It’s a common discussion not only in social theory but in mass-media. Nonetheless, we usually adapt ourselves to this kind of techno-vigilance in order to be part of our own society. In fact, for many people everyday life is oriented within a grid that–following Costa (49)–goes from “fingerprint” to “digital footprint.” As Costa states: “On the one hand, the actual or possible observation of a biological individual; on the other hand, the construction of a statistical simulation of what could be an identity, which functions as a reducing but highly effective mirror” (49). In addition, this social control device is bonded to important transformations of subjectivity. Each person in social media not only displays a “show of the self” (Sibilia 9) but also innocently offers this “self” to be captured by data mining.

d. Digital culture has produced a vast widening of contents in the form of texts, images and sounds, but rarely does this widening go with the necessary skills to produce critical judgment. A spreading phenomenon in digital culture such as fake news is one obvious but nevertheless highly significant example that illustrates the lack of judgment that is generated by contemporary mainstream digital culture. Additionally, this lack of judgment can be tied to a lack of memory due to overinformation. Speaking about images’ proliferation online–and the very short time they “survive” as visible in social media–Diogo Bornhausen points out to what extent data production today completely surpasses our capacities of consuming. Even if all these images are allocated in a virtual memory, “the system selects what will be seen, giving value to some results to the detriment of others.” (Bornhausen 8, my translation).

e. The concealment of materiality in mainstream digital culture also influences how we make sense in everyday life. Through the idea of virtuality and telematic shortening of distances, digital culture tends to make invisible not only the materiality of hardware, all along with its way of shaping life and differences in regards to material conditions of existence and geopolitical relationships but, at the same time, it tends to make invisible the ties between the materiality of hardware and software. As if a world of “immaterial” bytes would not collapse, for instance, without electricity.

The recognition of these–and possibly other–characteristics of mainstream digital culture becomes a necessary first step in the imagination of alternative ways of producing and experiencing e-lit. I would say that e-lit based on a diverted digital imagination frequently exhibits artistic nuances that confront those mainstream digital culture traits. In relation to the above list, I think that experimental e-lit contests each item by strategies such as: the overlapping of new and anachronistic technologies (item a); the messing with digital data in order to deconstruct its allegedly neutrality (item b); the unmasking of techno-vigilance (item c); the exhibiting of renewed politics of memory (item d) and the defamiliarization of digital interfaces in order to make them more “visible” (item e), among other possibilities. A second step drives us to cultural genealogies that go back to avant-gardes. This gives me the opportunity to resume the argument I posed at the beginning of this essay. My approach re-signifies an argument developed in the eighties by Andreas Huyssen, which is worth revisiting when considering the relationship between the arts, technology and mass culture.

2. After the Great Divide?

Andreas Huyssen’s book is titled After the Great Divide: Modernism, Mass Culture, Postmodernism and was published in 1986. For the author, “Modernism constituted itself through a conscious strategy of exclusion, an anxiety of contamination by its other: an increasingly consuming and engulfing mass culture.” (vii). And despite the many moves tending to destabilize this opposition all along the 20th Century, it remained resilient at least until the emergence of postmodernism, which meant a challenge to the high/low dichotomy. Even if we usually do not speak a lot about postmodernism any more–I think the notion of globalization swallowed the concept, but I am not going to follow that road–Huyssen’s core argument, which I agree with, is that we need not mix up modernism and the avant-garde. In fact, the same distinction is clearly made by Jochen Schulte-Sasse in his comprehensive foreword to the translation into English of Peter Bürger’sTheory of the Avant-Garde (xiv-xv). Although they share many traits, experimentalism being one of them, they differ in relation to the notion of autonomy of the arts. In that sense, Adorno’s theory, for instance, was a theory of modernism, experimentalism, novelty and artistic autonomy. To me, Adorno’s definition of experimentalism in arts remains valid. While slightly preferring modernism to the avant-garde–a preference that is not necessary to my own choice–Adorno explains in his Aesthetic Theory that “the gesture of experimentation [is] the name given for artistic practices that are obligatory new” (24), mainly because pre-established and secure forms and contents have become historically non-viable. On the contrary, mass culture usually depends on proven, profitable, mechanisms now and then a bit transformed to give a sense of novelty, but does not comprise the very new, which is unpredictable. That is the reason why, in Huyssen’s words “Adorno was the theorist par excellence of the Great Divide” (ix).

A possible formula for modernism could then be experimentalism minus mass culture. On the contrary, the historical avant-garde implied in many cases experimentalism plus mass culture. In particular, because at least since the beginning of the 20th Century, everyday life has embedded mass culture and technologies associated with it, in unprecedented ways, transforming percepts, affects and concepts (Deleuze and Guattari, What is Philosophy?). Of course, throughout the 20th Century up to the present, this process has only increased. Life has become an omnipresent and unprecedented technological space. The general technification of the world over the last century on a planetary scale, has literally become an atmosphere. How could art be apart from that? How can it maintain a separation from life? Quoting Huyssen one more time: ”(…) like the historical avant-garde though in very different ways, postmodernism rejects the theories and practices of the Great Divide.” (viii).

In regards to experimental e-lit, the narrow/broader audience issue, and even the high and lowbrow culture gap, we might better think of our particular creation of born digital literature as the return of the living dead. I mean, as we have just seen in relation to Huyssen’s argument, at least since the postmodern cultural debates in the eighties–that were a consequence of a transformed art scene by artistic movements that were under way since the late sixties–many of us thought that this specific Great Divide had been to some extent erased. However, it has survived more or less intact, and in our very own e-lit field and community.

Since I am born and raised in Buenos Aires, I will put my argument in terms of a quite well-known Argentine novel, many times read as postmodernist: Boquitas pintadas. Un folletín. [Heartbreak Tango. A Serial] by Manuel Puig. My formula “experimentalism + mass culture” applies here perfectly due to how this novel deals with the relationship between literature and mass culture. The novel imaginary is close to mass media discourses dated in 20th Century thirties and forties, such as tango and bolero songs and radio soap operas. There are also narrative devices appropriated from mass media genres such as serialized-melodramatic novels–for instance, the division not in chapters but in episodes and a recap of previous events in the middle of the text. At the same time, we find a proliferation of experimental devices that require a more self-reflective reader. For example, the fracture of the story’s temporal linearity, stream of consciousness monologs, letters and multiple allegedly transcribed texts as taken from everyday life–the obituary at the very beginning of the novel, police reports, medical records, among others.

Puig published Heartbreak tango in Argentina in 1969; since then it has been translated into 30 languages. Suzanne Jill Levine translated the novel into English in 1973; and only in English has it been reissued six or seven times, one of them by Penguin Classics. In some way, the novel manages to appeal to different kinds of readers. Some of them are only interested in the melodramatic love story and do not pay much attention to the experimental devices, which nevertheless–and this is crucial–they have to go through in order to keep up with the story–therefore, experimentalism re-shapes the meaning of melodrama itself. Others are more interested in the realistic depiction of small-town gossip and petty bourgeoisie’s hypocrisy in small rural towns in Argentina. And then there may be other ones who focus on the experimental devices as a disruptive way to re-signify all the rest.

In regards to this example, and finally moving on to e-lit, I find myself in a sort of predicament. I wrote several times about Puig’s novels. My interest in these novels had absolutely to do with their merging of experimentalism and mass culture on which I am basing my argumentation in this essay. How is it then that I ended up dealing with a kind of literature whose experimentalism led it many times far away from mass culture? Paradoxically, it came about because technology was already interwoven with mass media in everyday life. That is to say, for the same reasons that led me to read Puig’s novels in the first place, Heartbreak Tango included. Of course, it takes two to tango. In regards to e-lit, I would like not to dance the afterlife of the Great Divide anymore.

Of course, this entails some problems. E-lit found the best conditions for its development in academia and experimental artistic communities given that “one of e-literature’s founding principles”–Kathi Imman Berens remind us–“[is] that to read e-lit requires ‘non-trivial’ effort, whether that effort is physical interaction and/or cognitive complexity.” And that is not usually the case in mass culture. Even more, when analyzing Instagram poetry, Imman Berens also reminds us: “Instagram poetry’s aesthetic is indivisible from the surveillance capitalism infrastructure of social media metadata that makes algorithms agentic in ‘reading’ the reader.” I could not agree more.

Does it mean that e-lit’s experimental nature should be abandoned in order to embrace broader audiences? I do not think so. Does it mean then that e-lit should persist in isolation? I do not think so either. Instead, I am here trying to think how we could keep the better and discard the worse of both sides of the equation. In order to bridge the gap, we could explore how to denaturalize mainstream digital culture from within–something that many e-lit works already do–but stressing strategies to reaching more people. Our community is already engaged in this task via institutional efforts that I consider very valuable, since we are beginning to teach e-lit in conventional literature classes and to have e-lit tracks in more general literature conferences. This will eventually allow e-lit to be known by people who at present do not know about it. This is one way of acting. Another way is related to experimenting and thinking on, for instance, the potentialities of bots delivered through Twitter and certain other, more literary platforms such as Twine or Netprov. But this also poses some issues. For example, the debate on “e-lit third generation” fueled by Leonardo Flores is part of the same panorama. Flores coined the term “third generation” in an effort to update established historical accounts on e-lit:

I propose defining three generations (or waves) of electronic literature. The first one, much as defined by my predecessors, consists of pre-Web experimentation with electronic and digital media. The second generation begins with the Web in 1995 and continues to the present, consisting of innovative works created with custom interfaces and forms, mostly published in the open Web. The third generation, starting from around 2005 to the present, uses established platforms with massive user bases, such as social media networks, apps, mobile and touchscreen devices, and Web API services.

Although Flores recognizes that our present “third generation coexists with the previous one,” they are also too far away one from each other, given that from my point of view much of–but not all–third generation e-lit Flores has in mind–such as “Twine games, Twitter bots, Instagram poetry, GIFS, and image macro memes”–seems to be too comfortable with hegemonic digital culture.

In dialog with these initiatives, but stressing quite more e-lit’s experimental nature, I imagine other ways to appeal to broader publics without losing the impetus to build disruptive experiences within digital culture. Updating Huyssen’s argument, I think that e-lit experimental distinctiveness could be even a strength to appeal to broader audiences, because it shares a common ground with the historical avant-garde in regards to everyday techno-life. Despite when considering e-lit “second generation” (Hayles; Flores) critics usually read it as modernist, we could better consider it as “avant-gardish.” I am not saying that avant-garde movements really reached vast publics, but they posed the issue of how to interrupt everyday life from the inside. Many of them did so in regards to transformations of everyday life related to technology of their own time–telephone, cinema, radio, automobile’s velocity, transatlantic ships and so on. This was accomplished not only in an celebratory fashion as in Italian Futurism but in Dada and Surrealism: “by incorporating technology into art, the avant-garde liberated technology from its instrumental aspects and thus indermined both bourgeois notions of technology as progress and art as ‘natural,’ ‘autonomous,’ and ‘organic’” (Huyssen 11).

The kind of e-lit I am thinking about could be one that gets along with everyday techno-life, entertainment included, but it is undoubtedly not just entertainment. Critics have already read this, for instance, in certain types of textual videogames. When speaking about an “unnatural narratology of videogames,” Astrid Ensslin explained in a DiGRA keynote delivered in 2015 that though “games are unnatural narratives par excellence: because they comprise physical/logical impossibilities (…) some games are more unnatural than others: because they comprise defamiliarization and anti-mimeticism.” Although videogames are out of my field of expertise, the idea of defamiliarization and anti-mimeticism inside, and not outside, digital culture seems appealing. Hence, after a brief contextualization of Latin American pioneer experimental e-lit, I will consider more recent Latin American works that revert to appropriationism as a way to defamiliarize authorship within mainstream digital culture.

3. Latin American e-lit and its experimental nature

As far as I know, the first Latin American electronic works that can be associated to e-lit are Correcaminos (aka Caminante) (circ. 1965/1966) by Uruguayan Eduardo Darino, IBM (1966) by Argentinean Omar Gancedo, El canto del gallo. Poelectrones (1972) by Mexican Jesús Arellano and Le tombeau de Mallarme (1972) by Brazilian Erthos Albino de Souza. I outline a brief depiction of each in order to give the reader an idea of first generation “prehistoric” (Funkhouser 2007) experimental e-lit works in Latin America:

- Correcaminos (aka Caminante) is a programmed visual work that shows a walker, whose silhouette comprises letters and numbers in a visual poetry fashion. According to Darino’s testimony, the piece had several renditions over time. Having been since 1961 an experimental film maker and illustrator, but working around those years for a short term in a multinational oil company, Darino explored for artistic purposes how to use punch cards and mainframes in order to get a print version of a previously handmade silhouette. Two colleagues who worked in the same office and knew the punch card code aided him. By 1964, GE-235 (one of General Electric’s small mainframes) worked in tandem with GE DN-30 (Datanet-30) and used BASIC language, completed by Dartmouth College in 1964 (Fry). Darino states that in 1965 or 1966 he had access to BASIC programming language provided to him in beta testing by a publishing company in Buenos Aires. Shortly after, working as chief editor of the entertainment section in a newspaper, he used the telex to codify the silhouette and send it to the teletype printer. Correcaminos had also an animated film version completed at this time by capturing frames of the telex prints with a Keystone camera. Digital animation of the work was possible around the end of the eighties using first versions of Animator, which sooner became Autodesk Animator. At some point Darino recreated this work as an homage to Clemente Padín, a well-known Uruguayan mail artist and visual/performer poet since the sixties, who only experimented with e-lit–for instance in his Spam trashes–at the turn of 21th Century. In fact, in one of the work’s renditions the names “Eduardo” and “Clemente” are recognizable. Padín used the same idea/procedure of Correcaminos to create in 2003 with Flash his Homenaje to Wlademir Dias-Pino.

- IBM is a series of three short visual poems codified using an IBM 534 keypunch and processed by an IBM Card Interpreter. Each punch card, comprising the printed de-codified text on the middle horizontal line, was reproduced in the 20 issue of the journal Diagonal Cero in December 1966, edited in the city of La Plata, Argentina, by experimental visual artist and poet Edgardo Antonio Vigo. The explanation–not very clear though–about the equipment and the way it was used to create these poems was also published in the journal as an introduction to the work. The usual code for punch cards at the time was EBCDIC (Extended Binary Coded Decimal Interchange Code). Comparing the card perforations and the printed text of the poems in the same cards, the use of EBCDIC is demonstrable.

- El canto del gallo is a visual poem book, designed in an IBM MT72 composer. When explaining in an article how best-selling novelist Len Deighton composed in 1968 also with an IBM MT72 his novel about World War II, titled Bomber, Mathew Kirchembaum poses that Deighton’s was the first novel ever written on a word processor. He also explains that MT72 was another name for the IBM MTST (Magnetic Tape Selectric Typewriter).

- Finally, Le tombeau de Mallarme is a series of ten visual poems printed with the aid of a computer after the manipulation of software prepared for temperature measurement, and accessible to de Souza due to his work as an engineer in the Brazilian oil company Petrobras. At the same time, Erthos Albino de Souza produced other poetic experimentations with computers or computer peripherals. One of them was the transcodification in punch cards of the poem “Cidade” by Augusto de Campos. In addition, he produced a computer version of Augusto de Campos’ “Colidouescapo,” originally published in 1971. Interviewed in 1983 by Carlos Ávila–who published in 2004 the interview as a chapter of his book Poesia Pensada–de Souza says “When Augusto did his ‘Colidouescapo,’ which is a collage of word fragments, I did it with the computer, including all possible permutations.” [de Souza in Ávila 65, my translation]. Compared with the poem by de Campos–a well-known concrete poet who later on “remediated” some of his print visual poems in Flash–de Souza’s computer version only remained as a sort of hidden experiment.

It is not the aim of this essay to present a history of Latin American e-lit. If I mention these pioneers in some detail, it is because they were part of the poetic movement that contributed to the experimental nature Latin American e-lit has acquired since then, among other possibilities, in the fashion of visual, kinetic and/or combinatory poetry. The sixties and early seventies were in Latin America times of technological modernization, coinciding with the progressive spread of mainframes in business and government agencies. As it was not yet the time of personal computers, experiences of this kind were more or less isolated. But the actors behind technology, modernization and experimentalism were all committed to the search for “the new.” At the same time, those decades were also politically turbulent and several of the poets mentioned before entangled their experimentalism, in particular since mid-sixties, with social critique, something that will also persist as a relevant aspect in Latin American e-lit. In Gancedo’s IBM, for example, technological modernization and subjugated indigenous cultures encountered each other in no predictable ways. In fact, Gancedo’s electronic poems can be linked both to the very new–IBM gives not only the title to the poems but the poems’ medium–and to ancient cultures, since the verses obscurely allude to forests, resounding indigenous drums and indigenous people who die. We can add a similar consideration about Arellano, as many of his “poelectrones” are very “modern” in a techno-international way. Cybernetics for Arellano is a repeated significant and “to poelectronize” becomes a recurrent neologism. But my point is that Arellano entangles this kind of references to new global technolgies–along with the use of the very new IBM MT72–with the depiction of political issues and local inequalities. In the same vein as Gancedo, his verses are not always transparent but, still, we can read about poor peasants, big cities’ famished masses, bankers, politics and priests all branded as worms.

In that sense, Latin American e-lit was born altogether experimental, international and also grounded in local economic and political issues. While Emmett Williams produced in the United States his IBM generative poems in 1966, Gancedo produced in Argentina his own. Presumably, neither author knew about the other. Although both works that share the same title are not alike in regards to their realization, IBM was definitely in the air, as the unquestionable corporate leader in regards to computers. (Something that is politicized, not just stated in Gancedo’s IBM poems.)

A detailed consideration of the way experimentalism and politics entangle in contemporary Latin American e-lit goes beyond the scope of this essay. I addressed the topic in previous essays (2017, 2019) and Milton Läufer and I presented a paper related to the matter about Mexican Eugenio Tisselli’s and Argentinean Belén Gache’s e-lit works in the ELO Conference 2019 in Cork–“War from the periphery: appropriation and error in works of linguistic-political bellicosity.” By tracing Latin American e-lit back to its roots, I have only intended to put in perspective its experimental nature. And this, in turn might allow me to pose another scenario that might offer one chance, among possible others, for bridging the gap between e-lit and a more audience-oriented electronic literature.

4. Experimentalism, anti-authorship trends and mass culture

The scenario I would like to explore revolves around anti-authorship trends in contemporary digital culture. In particular in relation to experimental e-lit and digitized, lowbrow literature in the vein of online fanfiction. Admittedly, these two practices could not be more different in the way that audiences are targeted, works are circulated and self-reflective literary consciousness is created. But despite their many differences, a sort of common ground can be established between them in relation to how they conceive the role of the author and community building in literature.

The kind of e-lit I am thinking of can be associated with uncreative writing, conceptual writing, flarf, spam, generative poetry and any other language experimentation more or less related to appropriationism (Goldsmith). While genealogies for these practices can be traced back to specific historical avant-garde movements such as Dadaism and Surrealism that emphasized collective–in same cases anonymous–creation, up to neo avant-garde movements such as Fluxus, it is usually accepted that appropriationism gained momentum in digital culture. And despite remix has become nowadays almost a commonplace, there are still interesting cases. To give only a couple of relatively well-known examples in Argentinean e-lit, we can mention Peronismo (spam) (2010), by Charly Gradin, with programming assistance by Alejo Rotemberg, or IP-Poetry (2004/2006-present) by Gustavo Romano, a more complex piece programmed by Milton Läufer. Both works take Internet searches to trigger new poetic digital writings. In Gradin’s piece, the “seed phrase” that triggers online search is “El peronismo es como…” (Peronism is like…), a phrase absolutely bonded to Argentinean political history, being a kind of homage not without slight irony; in Romano’s piece there are numerous “seed phrases,” many times depending on the specific location of the work when presented as an installation. Sometimes the seed phrases are even verses pulled out of well-known poetry books, for instance, Federico García Lorca’s Poet in New York (1929). In the former, the final text emerged after the author’s manipulation of the online findings. It is presented in a kind of real time word processor going forward and backward when a typo needs to be corrected–white letters on an electric green screen accompanied by an electronic music remix: Mig Cosa Minimal Techno v.2–. In the latter, texts are produced by the programmed algorithm. Numerous readers have collaborated over the years providing seed phrases or verses, but it is always the algorithm, in the end, that selects and combines the resultant texts. These are then recited by four robots displayed as speakers mounted inside acoustic boxes, each of them having a screen in their front (Kozak, “Latin American Electronic Literature” 63). Human or machine produced–a topic I cannot develop here, but worth considering as Weintraub did concerning IP Poetry and its posthumanism–both works address the Internet as a symbolic reservoir of knowledge, passions, language, errors and more. Though oriented by Internet browsers that are not neutral but related at least to economic interests, this symbolic reservoir can be seen also as a chaotic Aleph that serves as a substrate for rearranging new memories out of the Internet’s collective language artifact.

Considering literary fanfiction and its possible relation to anti-authorship trends, and setting aside films, comics and videogames, it is obvious that appropriation and rewriting of favorite texts is basically the core of fanfiction. In order to discuss how to bridge the gap between “narrow” and “large” audiences, even high and lowbrow literature–without losing anything in the process–I picked up fanfic because of some sort of common ground, a tendency toward appropriationism, that it shares with experimentalism. In addition, I also picked it up because it is easily related to mass-culture genres – of the kind we have seen in Manuel Puig’s experimental rewriting of mass culture genres. Genres that are also in the core of fanfic culture: sci-fi, hard-boiled, melodrama, zombies’ stories, etc. To be sure, fanfic can be traced back to late 19th Century with mimeograph fanwriting around Sherlock Holmes (Jamison 4) and carried forward to science fiction fandom and fanzine culture. But it has increased exponentially in digital culture.

Strange as it might be, in fact, the comparison between experimental writing and fanfic within the anti-authorship digital culture atmosphere has already been made. For example, Darren Wershler–an experimental, conceptual, writer himself–wrote about it in “Conceptual Writing as Fanfiction”, his contribution to Anne Jamison’s book, published in 2013, Fic. Why Fanfic is Taking Over the World? Among aspects Wershler analyzes, it is worth to quote the followings: “Conceptual writing, like fanfiction, grows out of particular kinds of interpretive communities.” (336); “Fanfiction and conceptual writing have both been fueled by the rapid growth of networked digital media” (339); “Where fanfiction shifts characters to other settings, conceptual writing shifts text to other discursive contexts.” (340)

I would add other traits closer to the authorship matter to extend the comparison. Some critics analyze the proliferation of different kinds of “writings” and self-published literature on the Internet as an actualization of Barthesian death of the author (Pérez Parejo in Morán Rodríguez 51). In Barthes view, both modernism and avant-gardes–by different means though–contributed to the desacrilization of the image of the Author (Barthes 144) reaching a point where a modern “text is not a line of words, releasing a single ‘theological’ meaning (the ‘message’ of the Author-God), but a multi-dimensional space, in which a variety of writings, none of them original, blend and clash.” (146). In a way, fanfiction “scriptors” act as there is no “sacred” author of the stories they appropriate, though their rewritings are also a kind of homage that restores the author as an inspiration. The endless rewritings of favorite literature works poses then paradoxical ways to approach to the category of authorship. It is not a complete denial of authorship but a different–diluted–way to treat it. When in her essay Morán Rodríguez brings the issue of the “death of the author,” it is ultimately to deny such a thing in fanfiction (51). Other critics read fanfic as the raising of multiple authors. Anne Jamison poses: “at its very essence, fanfic challenge the unique/solo model of authorship” (20), but from her standpoint this does not happen because of the death of the author but because everyone become an author: “The author is not dead. The author is legion” (13), she provocatively declares. The fact is that many critics whose topic is fanfic feel the necessity of arguing in relation to the “death of the author,” for the category of authorship enters a sort of crisis or at least changes within this literary practice. Given that, we could also say that the avant-garde premise that envisaged a world where everyone might become an artist could be a bit closer, though in an unexpected way. Indeed, aside the relative minor amount of cases where fanfic trespassed the borders of the fandom, whose authors became published and recognized within cultural industry– Fifty shades of grey being one of the most famous– not everyone in the fanfic community aspires to be an author. They prefer the anonymity. They write and read fanfic for the sake of it. For the pleasure of the stories themselves, for the sake of been part of a community who shares imaginary worlds. And better if they can read them free of charge–another issue I do not have the space to develop here. Would it then be possible to go beyond the avant-garde premise and write an oxymoronic avant-gardish fanfic?

Cristina Rivera Garza dedicated a part of her book Los muertos indóciles. Neoescrituras y desapropiación [Undocile Bodies. Neo-Writings and De-Appropriation] to how citational aesthetics–following Marjorie Perloff’s concept–gain place in Spanish language literary practices in the context of digital culture. After commenting strategies and literary devices such as plagiarism, endless re-writing or textual appropriation, she proposes the notion of “de-appropriation” to explain practices where not only someone appropriates texts written by others but also detaches the result from her/his own name. She speaks about an intensive and extensive de-appropriation, which could tend to make the name of the authors to even not appear on the covers of their published books (91). In fact, Rivera Garza’s notion of de-appropriation exceeds–in a utopic fashion maybe–many cases of conceptual writing where the category of author blurs but does not disappear either because there are conceptual writers who reaffirm attribution of an appropriated text–but not all of them practice this sort of attribution–or because the author’s individuality lies in the way she/he selects and reorganize the appropriate materials (Goldsmith 10). Ultimately the majority of works of experimental literature–experimental e-lit included–that appropriate, distort or take out of context, texts by other authors, being them well-known authors or just people posting anything on the Internet or social media, hold the name of the “appropriator” as a new author.

De-appropriation would also be a way to exceed the several paradoxes fanfic poses in relation to authorship. Of course, it could not apply to fanfic authors who have gone published–or aspire to go published–within the authorship copyright system, but to the ones that are only recognizable within the fanfic scene as a nick and get no economic profit of their writings. Morán Rodríguez poses though that in fanfic forums there are specific rules concerning the use of plots or other developments already published by other fanfic writers, and the obligation to ask permission for reproducing a certain fanfic on another platform (48). These obligations seem to me at odds with the liberty fanfic writers have in regards to the original authors’ copyright, a burden that brings back attribution in a field that could easily liberate itself from it all. As Darren Wershler concludes: “If makers of conceptual writing and fanfiction really desire to operate differently from culture at large (and I’m no longer sure that this was ever the case), they’d need to produce writers who are not interested in becoming celebrity authors, but are willing to dissolve away into the shadows before the laurels can be handed out.” (341) Then, both experimental writing–e-lit that plays with authorship included–and fanfic could take profit of a more intensive de-appropriation.

Another aspect shared by experimental e-lit and fanfiction that deserves attention is that of technological obsolescence, which results in the instability of many of these productions as they circulate in areas not sustained by strong economic investments. By operating largely outside the market, these writings are often ephemeral. Even if there are nowadays extensive fanfic online archives, many times texts that had lots of readers disappear without trace (Morán Rodríguez 50).Jamison also refers to obstacles when trying to access a certain text everyone was recommending in fanfic forums but it was hard to find online (2). It is well-known to what extent experimental e-lit is subjected to technological obsolescence that threatens its accessibility. The fact that Flash will not run on online browsers after December 2020 puts many of us in a race to finding alternatives in order to preserve a great amount of e-lit works. Aside from established artists who take a great deal of effort to updating their websites, there are others who do not have the means–time, economic resources and technical skills–to do it. In some geographies such as Latin America this is more usual than in others. For example, if readers want to access Charly Gradin’s peronismo spam, a search on Google or other Internet browsers is not the best solution. The original URL has been inoperative for many years, but browsers still redirect to it. Since last year, the work moved to a new online location but many people cannot find it yet.

As for the differences between both practices, I have already briefly pointed out some. I nevertheless emphasize that within these differences there are nuances that could approach one practice to the other. On the one hand, fanfic culture is part of mass culture typical genre system. The one that Adorno had strongly criticized in relation to the reproduction of the “ever the same” due to its schematism and standardization. We could not say anything alike about conceptual writing and experimental digital writing that “plays” with the notion of authorship. However, while fans are comfortably installed in mass culture genre system–science fiction, terror, police, melodrama, etc.–they also rarify it. This rarefication may be seen as a denaturalization as well. In particular, due to eroticization of the contents, the proliferation of new genres and the divergent links established between genre and gender. Women write the majority of fanfiction works, although men and people who are committed to gender declassification also participate. As Jamison argues: “Male/male erotic romance by straight women for straight women was just the beginning. Fanfiction transforms assumptions mainstram culture routinely makes about gender, sexuality, desire, and to what degree we want them to match up.” (19)

On the other hand, the degree of literary self-reflexivity in experimental writing is much greater than in fanfiction. Experimental (de)appropriationism implies a conscious use of a device, a literary resource that is not present in most fanfiction productions. But there is also a self-referential fanfic. And not only in the obvious case of the self-referentiality involved in all kinds of content crossings–intertextuality and crossovers–but in the works that Jamison specifically considers as meta-fic: discussion forums about fanfic content and productions of highly self-referential rewriting with regard to the typical procedures used by the fanfic community. Although this kind of self-referential procedures does not represent its main avenue, part of fanfiction can also show artistry, cultural self-consciousness and even meta-fiction devices. In that sense, Jamison explicitly speaks about cultural criticism and self-commentary in fanction (11).

Given the previous comparison, I’d like to address a possible Latin American ideal confluence between experimentalism and the spirit of fanfic. Two years ago, I asked a small group of colleagues at University of Buenos Aires whether they knew anything about fanfic or not. The only one who answered affirmatively–although he declared to not being interested in it all–was Pablo Katchadjian, an experimental/conceptual writer, who had to endure a long legal process due to María Kodama’s–Borges widow–plagiarism lawsuit. This leads me, finally, to some examples on how experimental literature becomes experimental e-lit and might also become something else, trespassing the borders of a small community.

5. Borges, (Kodama), Katchadjian, Läufer & Company

Pablo Katchadjian literary works are not digital, but they sometimes dialog with e-lit. For instance*, Mucho trabajo* (2011) [Heavy work, or, Lots of work] is a novel which would occupy around 200 pages in normal printing, but was published in an extremely reduced font in only 8 pages. The novel is illegible in first sight. The only way to read it is using a special magnifying glass or recurring to digital amplification. People have taken digital pictures and then expanded their size in order to read it, even with some difficulty. On the contrary, we could also not read it at all, and keep it as a conceptual artwork.

Another work that I find interesting in regards to my main argument is El Martín Fierro ordenado alfabéticamente (2007) [Martin Fierro in alphabetical order]. Martín Fierro, by José Hernández, is Argentine “national poem,” a narrative poem that tells the story of a transgressor gaucho who, in the poem’s first part published in 1872, ends living beyond the national territory with indigenous people. The poem has also a second part published in 1876 that narrates Martin Fierro’s social reinsertion in the “acceptable” society.

Katchadjian’s text is exactly what the title says. He put in alphabetical order the 2316 verses of the poem’s first part, and published the result in a small independent print he owned, IAP (Imprenta Argentina de Poesía). The choice of the first part of Martín Fierro, not the second one, is also important. Both texts display certain type of transgression, in two different levels though: in the original Martín Fierro, transgression had to do with the main character, an outsider; in Katchadjian’s, transgression is related to language experimentalism. The experimental gesture is oriented to not foreseeing any specific value of the results other than the literal. This gesture starts only with a question: what could happen if we put Martín Fierro’s first part in alphabetical order? We can keep only the conceptual, ironic, gesture and do not even bother reading the text. Nevertheless, we can also read it and find the very materiality of the poem’s language. Indeed, the alphabetical order gives a distinctive alliterative quality to the whole. Moreover, we could also put the work in the same universe with poetic digital bots such as @everyword, by Allison Parrish. The artist also launched this bot for the first time in 2007 and the bot’s main device is alphabetical order as well. Republishing El Martín Fierro ordenado alfabéticamente as a bot could perhaps be a “natural” update in regards to denaturalizing social media.

El Martín Fierro ordenado alfabéticamente intended to be part of a “national” experimental trilogy whose second episode was El Aleph engordado (2009) [The Fattened Aleph], the book that motivated Kodama’s lawsuit. I quote an article from an online British magazine on experimental literature–Minor Literature[s]–that refers to this work:

Two hundred copies were printed and distributed mostly among friends. The book was a remake of Argentine writer Jorge Luis Borges’ short story “The Aleph” through a procedure that was explained in a post-script: Katchadjian added 5,600 words to the original 4,000 of Borges’ “The Aleph” (…) In 2011, María Kodama, heir of Jorge Luis Borges’ literary estate, filed a criminal lawsuit accusing Pablo Katchadjian of plagiarism–clearly without reading the book’s post-script. According to Argentine legislation, this charge contemplates a prison sentence of up to six years. The case was dismissed by a lower court judge and Kodama’s lawyers appealed the ruling, which was confirmed by the Appeals Court. Kodama’s lawyers appealed yet again and the case was heard by the Appellate Court, which overturned the lower court and the Appeals Court’s ruling, and ordered the first instance judge to review his decision.

In short, the legal process went back and forward. At some point Katchadjian was indicted and some of his assets were frozen. It was not until 2017 that the case was dismissed, again, by the Appeals Court. In a disproportional measure, Kodama appealed again, to the Apellate Court (the highest court below the Supreme Court), but she did not followed the appeal and Katchadjian was finally acquitted. Nevertheless, disproportion and misunderstanding has always been at stake in the first place. Although this briefing of the whole story is necessary in case readers do not know it, it is not my intention to make this Kafkaesque trial the center of my argument. Instead, I would like to point out Argentinean Milton Läufer’s generative remake of Borges’ “The Aleph,” and stress one or two aspects.

El Aleph a dieta (hasta la ininteligibilidad) (2015) [The Aleph on a Diet (up to unintelligibility)] and El Aleph autocorregido (2016) [The Aleph autocorrected] exhibit algorithmic variations of Borges’ short story. In the first one, different words change randomly their color onto red, while they are crossed out and finally deleted. If we keep reading, the text progressively “loses weight” until illegibility. In the second, words appear first crossed out without any change of color, and then replaced for others, this time in red, which hyperlink to online dictionaries entries. There are also options of manual manipulation and the possibility to have the changes in Spanish, English or both languages.

El Aleph a dieta is dedicated to Pablo Katchadjian. It could not be otherwise. We are here in presence of an experimental e-lit work, by Läufer, based on another experimental work, by Katchadjian, based on the work of another experimental author, Borges. At least if we think about the multiple occasions–not only in his “Pierre Menard”–Borges himself appropriated other texts and reflected on appropriation. Something about every writer and scholar tried to convince Kodama, without any success. Läufer raised the bet including a disclaimer–sort of anti-disclaimer–which says (in Spanish, but I translate): “all rights of the original text are absolutely reserved to M. Kodama, to her and only, only, only her, Georgie’s prophet.”

Hence, I return to fanfic. Many fanfiction works also include disclaimers in order to not be reached by copyright guardians. This in fact has not prevented those who participate in fanfiction communities of being legally sued for plagiarism in several occasions. Henry Jenkins (2008) has reported large cases of lawsuits of this type in relation especially to audiovisual fanfiction. Interesting is his review of how the strategies of the publishing and audiovisual industry have varied even within the same companies that own copyright, going somewhat volatilely from the indifference to these legions of “authors,” to the legal demands, or also, the co-optation for advertising purposes.

In conclusion, it is not only that the two practices share a general resemblance within the copy&paste culture. They both actively exhibit their position within this culture, and not in the form of a vague and non-reflective acceptance of the spirit of the times. Asked Katchdjian about comparing experimental appropriationism and the one of fanfic, he stated that in experimental literature appropriationism is a conscious apparatus, a literary procedure, but not in fanfic. I am not so sure about that, or at least not in some cases. Of course, in the case of experimental literature, this is not surprising, since its self-reflective nature is evident. However, at least for part of the fanfic communities, it should not be surprising either. Nor should it be surprising that there are quite different fanfic communities. Nor that there are also fanfic works derived from Borges. In a magazine article on the fanfic phenomenon, Cristian Vázquez wondered: “And is it not a kind of fanfiction of Martín Fierro what Borges made in stories like “El fin” [“The end”] and “Biografía de Tadeo Isidoro Cruz” [“Biography of Tadeo Isidoro Cruz”]?” [my translation]. Given that fanfic is not really digital literature but digitized, I imagine then e-lit writers getting on board. We might have experimental digital fanfic. This would comprise the kind of defamiliarized devices e-lit already knows very well, and at the same time the appealing of the stories and imaginary worlds many people enjoy. Why not?

I have not intended here to establish a total equivalence between experimental e-lit and fanfiction. What I have presented are actually encounters and dis-encounters between two practices based on a common ground inscribed in contemporary digital culture. The (de)-appropriationism by which they manifest is part of the way they construct meaning within digital culture. The question that has led me to look at fanfiction, from the perspective of experimental e-lit, is based on the relative invisibility of e-lit for larger audiences, which of course does not apply to fanfiction. Digital literature is still in search of its readers. Fanfiction has plenty. However, if we think of the distance between them not quite as a gap but instead, as a threshold, productive exchanges between them come to the fore. I hope then that this essay can contribute to the ongoing discussion in our community in relation to surpassing the sort of “gaps” I’ve been dealing with here. I am not proposing to completely give up on experimental e-lit but to move its denaturalization of digital mainstream culture to other literary communities. For instance, I have been thinking about persuading some experimental e-lit makers to do what Manuel Puig did with his novels–but updated for our contemporary digital culture. Wouldn’t it be María Kodama’s worse nightmare if a whole fanfic community experimentally rewrites “The Aleph” as e-lit?

References

Adorno, Theun W. Aesthetic Theory.1970. London: Continuum, 2002.

Adorno, Theun W. and Max Horkheimer. Dialectic of Enlightenment. Philosophical Fragments. 1947.Trans. Edmund Jephcott. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2002.

Apprich, Clemens. “Introduction”. Pattern Discrimination. Clemens Apprich, et al. Minneapolis, USA: University of Minnesota Press / Lüneburg, Germany: meson press, 2018. ix-xii.

Arellano, Jesús. El canto del gallo. Poelectrones. 1972. México, DF: Universidad Autónoma de México, 1975, 2nd edition, expanded.

Ávila, Carlos. “O engenheiro da poesia”. Poesia pensada. Rio de Janeiro: 7 Letras, 2004. 60-74.

Barthes, Roland. “The Death of the Author.”1968. Trans. Stephen Heath. Image Music Text. London: Fontana, 1977. 142-148.

Borhnausen, Diogo. “Memória, disponibilidade e excesso: Sobre as (in) capacidades do consumo das memórias virtuais”, 2014. http://www.espm.br/download/Anais_Comunicon_2014/gts/gt_sete/GT07_BORNHAUSEN.pdf [Currently of line, Accessed 16 Oct. 2017]

Bruno, Fernanda. Máquinas de ver, modos de ser: vigilância, tecnologia e subjetividade. Porto Alegre: Editora Sulina, 2013.

Bucher, Taina. If then… Algorithmic Power and Politics. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2018.

Buck-Morss, Susan. Dreamworld and Catastrophe: The Passing of Mass Utopia in East and West. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 2000.

Bürger, Peter. Theory of the Avant-Garde. 1974. Trans. Michael Shaw. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1984.

Costa, Flavia. “Nuestros datos, ¿nosotros mismos?” Víctor Ramírez, Laia Manonelles y Daniel López del Rincón (Eds.), Corporalidades desafiantes: reconfiguraciones entre la materialidad y la discursividad. Barcelona: Editorial de la Universidad de Barcelona, 2018. 49-67.

Cramer, Florian. “Crapularity Hermeneutics: Interpretation as the Blind Spot of Analytics, Artificial Intelligence, and Other Algorithmic Producers of the Postapocalyptic Present”. Clemens Apprich et al.Pattern Discrimination. Minneapolis, USA: University of Minnesota Press / Lüneburg, Germany: meson press, 2018, 23-58.

Darino, Eduardo. E-mails to the author. December 27, 2019-January 30 2020.

Deleuze, Gilles and Felix Guattati. What is Philosophy? 1991. Trans. Hugh Tomlinson and Graham Burchell III. New York: Columbia University Press, 1996.

Ensslin, Astrid. “Videogames as Unnatural Narratives.” DiGRA2015, https://vimeo.com/132324039Accessed August 7, 2018.

Flores, Leonardo. “Third Generation Electronic Literature.” Electronic Book Review, April 7, 2019. http://electronicbookreview.com/essay/third-generation-electronic-literature/ Accessed September 14, 2019.

Fry, Don. “Don Fry history working in the Time Sharing Development Area.” June 7, 2018. http://ed-thelen.org/TS-history-DonFry-v01-01.html Accesed January 30, 2020.

Funkhouser, Christopher T. Prehistoric Digital Poetry: an Archaeology of Forms, 1959-1995. Tuscaloosa, Al.: The University of Alabama Press, 2007.

Galloway, Alexander. Gaming. Essays on Algorithmic Culture. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2006.

Gancedo, Omar. “IBM.” Diagonal Cero 20 (1966): 15-18.

Goldsmith, Kenneth. Uncreative Writing: Managing Writing in the Digital Age. New York: Columbia University Press, 2011.

Gradin, Charly. Peronismo (spam). 2010. http://peronismo.atspace.cc/ Accessed January 24, 2020.

Hayles, N. Katherine. “Electronic Literature: New Horizons for the Literary.” Notre Dame, Ind.: University of Notre Dame Press, 2008.

Heidegger, Martin. “The Question on Technology.” 1953. The Question Concerning Technology and Other Essays. Trans. William Lovitt. New York & London: Garland Publishing, 1977. 3-35.

Huyssen, Andreas. After the Great Divide. Modernism, Mass Culture, Postmodernism. Bloomington, Ind.: Indiana University Press, 1986.

Inman Berens, Kathi. “E-Lit’s #1 Hit: Is Instagram Poetry E-literature?” Electronic Book Review, 04-07-2019, http://electronicbookreview.com/essay/e-lits-1-hit-is-instagram-poetry-e-literature/ Accessed September 14, 2019.

Jamison, Anne. “Introduction.” *Fic. Why Fanfic is Taking Over the World?*Dallas: Smart Pop, 2013. 1-28.

Jenkins, Henry*. Convergence Culture. La cultura de la convergencia de los medios de Comunicación*. 2006. Trans. Pablo Hermida Lazcano. Barcelona: Paidós, 2008.

Katchadjian, Pablo. El Martín Fierro ordenado alfabéticamente. Buenos Aires, IAP, 2007.

---. El Aleph engordado. Buenos Aires, IAP, 2009.

---. Mucho trabajo. Buenos Aires, Spiral Jetty, 2011.

Kirschenbaum, Matthew. “The Book-Writing Machine. What was the first novel ever written on a word processor?” Slate Book Review, 03-01-2013, https://slate.com/culture/2013/03/len-deightons-bomber-the-first-book-ever-written-on-a-word-processor.html Accessed September 14, 2019.

Kozak, Claudia. “Latin American Electronic Literature: When, Where and Why.” María Mencía (ed.). #WomenTechLit, West Virginia University Press, Morgantown, WV, USA, 2017. 55-72.

---. “Poéticas/Políticas de la materialidad en la poesía digital latinoamericana.” Perífrasis. Revista de Literatura, Teoría y Crítica 20 (2019): 71-93.

--- and Läufer, Milton. “War from the periphery: appropriation and error in works of linguistic-political bellicosity.” Peripheries. ELO Conference. University College Cork. Cork, Ireland, 17 July 2019.

Läufer, Milton. El Aleph a dieta (hasta la ininteligibilidad). 2015. http://www.miltonlaufer.com.ar/aleph/ Accessed August 14, 2018.

---. El Aleph autocorregido. 2016. http://www.miltonlaufer.com.ar/alephautocorrect/ Accessed August 14, 2018.

Marcuse, Herbert. One-Dimensional Man. Studies in the ideology of advanced industrial society. 1964. New York & London: Routledge, 2002.

Minor Literature[s]. “On the Perils of Literary Freedom: Pablo Katchadjian and The Fattened Aleph.” https://minorliteratures.com/2015/06/28/on-the-perils-of-literary-freedom-pablo-katchadjians-unfair-trial/# Accessed August 10, 2018.

Morán Rodríguez, Carmen. “Li(ink)teratura de kiosko cibernético: Fanfictions en la red.” Cuadernos de Literatura, 12/23 (2007): 27-53.

Morozov, Evgeny. La locura del solucionismo tecnológico. Trans. Nancy Viviana Piñeiro. Buenos Aires: Katz Editores, 2015.

Padín, Clemente. Spam Trashes. CD-ROM, 2002.

---. Homenaje a Wlademir Dias-Pino. 2003. Antología litElat. V. 1. Flores, Leonarod; Kozak, Claudia and Mata, Rodolfo, editors, 2020, forthcoming.

Parrish, Allison. “@everyword in context.” Decontextualize, 2011. http://www.decontextualize.com/2011/10/everyword-on-gawker/ Accessed January 25, 2020.

Perloff, Marjorie. Unoriginal Genius: Poetry by Other Means in the New Century. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2010.

Puig, Manuel. Heartbreak Tango. A Serial.1969. Trans. Susan Jill-Levine. New York: Dutton, 1973.

Romano, Gustavo. IP Poetry. 2004/2006. https://ip-poetry.findelmundo.com.ar/ Accesed January 24, 2020.

Rivera Garza, Cristina. Los muertos indóciles. Neoescrituras y desapropiación. México DF: Tusquets, 2013.

Sadin, Éric. La humanidad aumentada. La administración digital del mundo. 2013.Trans. Javier Blanco and Cecilia Paccazochi. Buenos Aires: Caja Negra, 2017.

---. La siliconización del mundo. La irresistible expansion del liberalismo digital. 2017. Trans. Margarita Martínez. Buenos Aires: Caja Negra, 2018.

Schulte-Sasse, Jochen. “Foreword: Theory of Modernism versus Theory of the Avant-Garde.” Theory of the Avant-Garde. By Peter Bürger. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1984. vii-lv.

Sibilia, Paula. La intimidad como espectáculo. Buenos Aires: Fondo de Cultura Económica, 2008.

Souza, Erthos Albino de. “Le tombeau de Mallarmé.” 1972. Mallarmé. Augusto de Campos, Décio Pignatari y Haroldo de Campos. São Paulo: Perspectiva, 1991, 195-216.

Striphas, Ted. “Algorithmic culture.” European Journal of Cultural Studies18/4-5 (2015): 395-412.

Vázquez, Cristian. “Game of Thrones, la fanfiction y un jardín de senderos que se bifurcan.” Letras Libres, 2017, https://www.letraslibres.com/mexico/literatura/game-of-thrones-la-fanfiction-y-un-jardin-senderos-que-se-bifurcan Accesed September 15, 2019.

Weintraub, Scott. “Machine (Self-)Consciousness: On Gustavo Romano’s Electronic Poetics.” Paper presented at the Conference “Latin American Cybercultural Studies: Exploring New Paradigms and Analytical Approaches”. Liverpool, UK, University of Liverpool, May 19-20, 2011. http://ip-poetry.findelmundo.com.ar/MsC.html Accesed August 1, 2015.

Wershler, Darren. “Conceptual Writing as Fanfiction.” Anne Jamison (ed.), Fic. Why Fanfic is Taking Over the World? Dallas: Smart Pop, 2013. 333-375.

Williams, Raymond. Marxism and Literature. [1977]. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 1985.

Cite this article

Kozak, Claudia. "Electronic Literature Experimentalism Beyond the Great Divide. A Latin American Perspective" Electronic Book Review, 1 March 2020, https://doi.org/10.7273/rpbk-9669