From Analog Shuffle to Digital Remix: Translating Robert Grenier’s Sentences

Presenting the writerly and highly remixable analog edition as both pre- and proto-digital, Carly Schnitzler revisits Robert Grenier’s Sentences. She compares the analog version of “shuffle literature” (in choosing the term, she follows the footsteps of Nick Monfort and Zuzana Husarova), published as five hundred index cards stored in a box, with its 2003 digitized edition. Such comparison serves to set the ground to investigate further the potential for writerly literary forms of what Lawrence Lessig once described as Read/Write culture, beyond the analog/digital dichotomy. The detailed and attentive analysis proposed by Schnitzler leads to somewhat surprising conclusions, where the algorithmically driven automatic choices present far less potential for meaningful and open-ended interaction with the text. Simultaneously, all the nuances surrounding the relatively early efforts at rendering Sentences as an object of networked reading are demonstrated here, including hints on digitization as a practice with its own history.

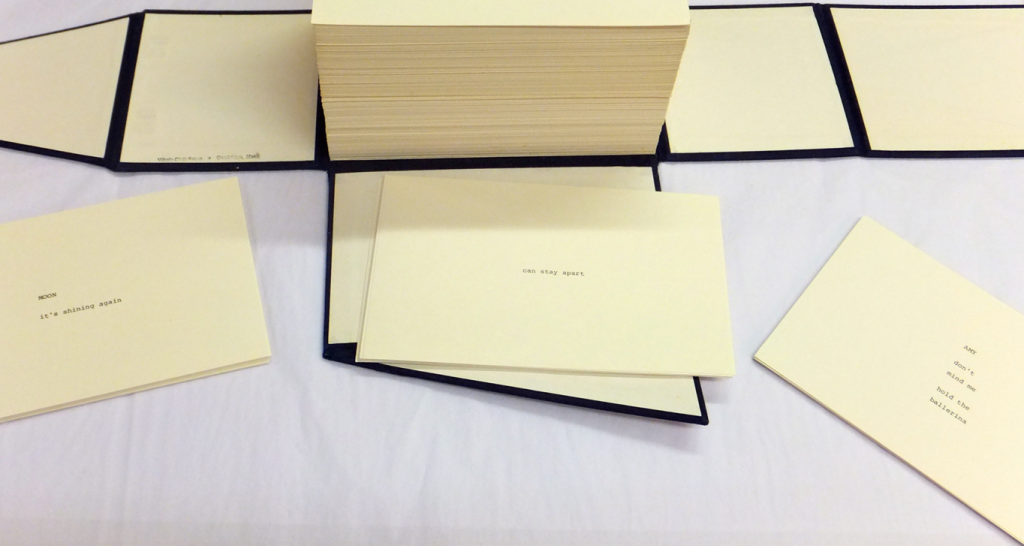

From 1971 to 1978, Language poet Robert Grenier wrote, then typed on an IBM Selectric typewriter, five hundred small lyric poems: really, pieces of a poem or poems to compose Sentences. Sentences is a poem composed on five hundred index cards and housed in a small box. This allows you, the reader, to shuffle them and spread them out, placing them in the (maybe non-linear) order that suits your experience of the poem. Unbound from the confines of the codex, you can create—one long poem, many shorter ones in succession, an expansive Un Coup de Des-esque constellation.

Sentences is a radically “writerly” poem in Roland Barthes’s original terms—one that allows for the text of the poem to be a site where the reader necessarily must produce meaning from the work not expressly “author”-ized by its creator. “The writerly text is a perpetual present,” Barthes writes in S/Z, “upon which no consequent language (which would inevitably make it past) can be superimposed; the writerly text is ourselves writing” (5). The device within Sentences largely enabling its “writerly”-ness is parataxis. Each index card is a free agent within the poem, operating as a discrete unit. Their combination, and any meaning that ensues from their combination, is the work of the reader “writing,” and the work of the reader “writing” only, since no words exist between index cards to indicate coordination or subordination. Grenier verbalizes this paratactic, writerly ethos for Sentences in a 1976 letter to Burroughs Mitchell, the editor-in-chief of Charles Scribner’s Sons: “I’d really like the reader to really participate in the work,” he writes, “such that both make an experience” (“Letter”).

In 2003, Whale Cloth Press, the original publisher of Sentences, digitized the work twenty-five years after its analog publication. The digital edition makes Sentences much more accessible to a wider audience, by removing the box and index cards and algorithmically doing the work of shuffling for you. The order of the cards are randomized and presented to viewers in a linear order with each new experience of Sentences.

The digital edition also prompts an exploration of the frictions that exist between what I will call analog shuffle and digital remix. Friction, in this context, is the resistance that happens in the phase change from analog to digital—the pieces of the analog that do not fully translate, that do not fully move into the digital. The analog form of Sentences, with its custom, cloth-covered, multi-jointed box housing five hundred index cards, is formally much closer to the remix culture of the digital than it initially might seem. “Remix is collage,” Lawrence Lessig says in his seminal book Remix: Making Art and Commerce Thrive in the Hybrid Economy (76). It is the process of repurposing and recontextualizing content from an ever-expanding multimedia archive to create something “new” (69). Remix is a combinatory act of writerly creation uniquely suited to a digital ecology, but Sentences provokes us to think about the concept in an analog environment as a proto-digital work.

To be clear, the analog edition of Sentences is inarguably material and physical, its own analog archive. The index card technique of composition is decidedly pre-digital, though I also wish to argue that this means of composition shares some common ground with the proto-digital, especially as it relates to remix. In a 1967 interview with Herbert Gold of The Paris Review, Vladimir Nabokov, who famously composed Lolita and many more of his novels on index cards, said of his process: “the pattern of the thing precedes the thing. I fill in the gaps of the crossword at any spot I happen to choose. These bits I write on index cards until the novel is done” (Gold). The index card technique of composition is also frequently employed by screenwriters, who use them for their proximity to represent discrete scenes or stills from scenes (Kellogg). Novels, plays, and films, though amenable to this kind of composition, are linear in their final forms, despite the non-linearity the index cards initially allow in the drafting process. Grenier’s Sentences, with its final form in index cards, renders this non-linearity integral. Digital media scholars Nick Montfort and Zuzana Husárová in their essay “Shuffle Literature and the Hand of Fate,” coin the term “shuffle literature,” which includes Grenier’s Sentences and other non-linear analog experimental works that are “meant to be shuffled and read [in their] entirety” (1). Shuffling, in works like Sentences and Oulipian Raymond Queneau’s Cent mille milliards de poems (I’ve made a bot doing this work of shuffling), “rearrange[s] the discourse and model processes of memory, random association, and cognition” (2).

Specifically, Sentences rearranges these things to exist in Barthes’s “perpetual present” (S/Z, 5). Fellow Language poet Ron Silliman notes of Grenier’s Sentences: “By removing “before” & “after” from the book of poetry—or at least by rendering it visibly arbitrary—Grenier has in fact created ‘new sentences’ in a way that had not been previously possible, let alone contemplated” (Silliman). This is the genius of Sentences—it is a material poem that creates a “perpetual present” wrapped up in the reader’s experience of the poem (Barthes, S/Z, 5). In the “perpetual present,” Sentences, taking its title seriously, is a work that is always complete, in whatever order, establishing presence. Sentences are sets of words complete unto themselves, movable wholes in the reader’s experience of them. Barthes, in The Pleasure of the Text, goes so far as to describe the writer in terms of sentences: “A writer is not someone who expresses his thoughts, his passion, or his imagination in sentences, but someone who thinks in sentences: A Sentence-Thinker (i.e. not altogether a thinker and not altogether a sentence-parser)” (50-1, emphasis in original). This is to say, writers think in wholes, in complete, discrete, movable units—like, for example, Grenier’s index card lyric stanzas. So, in Grenier’s Sentences, the reader is not only encouraged to be writerly by combining, shuffling, and reordering the index cards, but also by thinking in the very same units in which the writer does.

By giving the reader of Sentences both the ability and the prerogative to craft meaning from the text, Grenier privileges the moment of experience over the mutable content of the poem. In this, he also enables the readerly experience of simultaneity to emphasize the exceptional experience of the moment, Barthes’s “perpetual present” (S/Z, 5). The index cards of Sentences encourage a paratactic reading—they are five hundred moments at once, in their raw form, as a pile of cards in a box. Our readerly experience of them then traces a path through those individual moments, based on a combination of chance encounter between cards in proximity and our readerly eye working to spot a route through. This is what I’ll call the analog shuffle. An important thing to note about analog shuffle is that it is a non-linear, spatially implicated experience. For Sentences in particular, the analog shuffle necessary to read and write the work is tactile, it blurs the line between a game and a collection of poetry, privileging in-the-moment experience. Within the experience of the poem, cards fall this way and that, up, down, and to the sides. There are stacks of them, small piles that create physical depth. Edges of words on some cards can catch our eye under others, to the sides of them. The physical chance involved in the analog shuffle is Montfort’s “Hand of Fate” “highlight[ing] present moments and their continuity in the mind” (10).

In analog shuffle, meaning is optional. It is something a reader opts into and creates for themselves. Cards are pulled, ordered, re-ordered, grouped, re-arranged. You pull “why you say you see later” next to

“HAPPY TO BE WITH YOU

knew we knew each other,”

and then could switch them:

“HAPPY TO BE WITH YOU

knew we knew each other,”

“why you say you see later” (Grenier).

The “later” in these lyrics, when reversed, functions quite differently—in the former, it, as an inversion of “see you later” makes the relationship implicated in the “you” and the implied “I” and “we” resolved in the second stanza, the “you see later” becomes “we knew each other” in the second. The “you” and the “I” “knew” each other all along, eclipsing the transition from present to past tense, making the tenses irrelevant to how time is actually functioning between the lyrics in this combination. When reversed, though, the second lyric “why you say you see later” becomes a gesture to something to come, the “later” is unresolved by these two exemplary lyrics in combination. In this way, Grenier allows for, but doesn’t demand, time to eddy in Sentences, the first example being an example of time working in a closed loop, an eddy, and the second being an example of two time scales working at once. The possibility for simultaneity of event, of lyric, in a “perpetual present” demonstrates the unique relationship the analog shuffle has to time, and it’s all in the hands of the reader (Barthes, S/Z, 5).

So too, explicitly calling the verses on Grenier’s index cards ‘lyrics’ implicates the personhoods in Sentences, the human presences in the work. In a standard lyric usage, the reader is merely reading about another “I,” the “I” of the poet in relation to another. In Sentences, this conventional use is retained, but the writerly reader is also invited to see themselves in the “I,” as an active participant in the work.

This simultaneity and presence at once, particularly in relation to the writerly reader, is also notably proto-digital in form. Lawrence Lessig introduced the concept of “Read/Write Culture” in his aforementioned book Remix to describe what happens when writerly readers “add to the culture they read by creating and re-creating the culture around them” (28). Lessig gives a finer point to Barthes’s writerly reader, placing them in a media ecology—the digital—with a specific enterprise—remix. Lessig talks about “Read/Write Culture” (“RW” for short, in Lessig’s originals) in particular relation to the digital, contrasting it with much of the “Read Only” culture of the analog. “Read Only” media is media that is readerly, that is merely consumed, and not changed or augmented, by the reader. Lessig says of “Read Only”-ness of the analog:

“These are the inherent— we could say ‘natural’— limitations of analog technology. From the consumer’s perspective, they were bugs. … But from the perspective of the content industry, these limitations in analog technology were not bugs. They were features. They were aspects of the technology that made the content industry possible” (37).

In other words, the analog is, largely due to its business model, unfriendly to Read/Write culture. But Robert Grenier’s Sentences can bridge the gap between the analog and digital in this way, as a technically analog work that explicitly participates in Read/Write culture. Lessig later notes that “digital technology removed the constraints that had bound culture to particular analog tokens of RO culture” (38). But, since Sentences did not obey these constraints in the first place, it occupies an important place between the analog and the digital. Lessig notes that Read/Write culture finds its natural home in the digital ecosystem of “remix” (76). “Whether text or beyond text, remix is collage;” Lessig says, “it comes from combining elements of RO culture; it succeeds by leveraging the meaning created by the reference to build something new” (76).

Interestingly, the digital version of Robert Grenier’s Sentences is much more “Read Only” than “Read/Write,” collaged from the elements of a single body of materials. In the digital version, an algorithm does the work of shuffling for you and cards are presented in a linear order, one at a time. Each of these were different digital “cards” I encountered in the digital edition of Sentences: “didn’t we turn / off the television” // “sweet tooth tonight I hope I hope” // “AMY / could you get my spoon.” Ron Silliman, Grenier’s compatriot Language poet who beta-tested the digital edition of Sentences wanted to see the possibilities of the digitization, saying in a blog post about the work: “What’s occasioned my thinking on Grenier this week has been a chance to beta test a still unannounced site that, when complete, will make Sentences available in a fully equivalent electronic version, a wonderful solution.” The paratactic and “Read/Write” possibilities of the analog are ultimately lost here, though. It is not, as Silliman hopes, “a fully equivalent electronic version.” The order of the cards is set by the simple randomization algorithm and the reader is only left to read the lyrics in the order you’re made to encounter them. We lose the tactility, serendipity, and play of the analog version here, made to be passive readers, clicking ‘next.’ Paul Stephens briefly notes in his recent article “Really ‘Reading In’: A Media-Archival History of Robert Grenier’s Sentences” that:

“The roughly 3,300 words of Sentences can be clicked through quickly, and unless one opens multiple web browsers, only one card can be viewed at a time. Though the typewriter font is approximated in the web version, much of the sense of Grenier’s writing materials is lost, as is the physical heft of the six-pound box” (282).

The move between the analog and digital in this work would be to go from analog shuffle to digital remix, a form in which readers could manipulate the five hundred lyrics of Sentences. The limitations that Whale Cloth Press bumps up against in its digitization efforts demonstrates the friction in that move. They are beholden to a single tab, on a single web-browser. Silliman’s optimism may not be all misplaced, though, and I do not wish to demean the digitization and accessibility efforts of Whale Cloth Press—after all, I only had access to Sentences through the digital edition myself. Whale Cloth created the digital edition in 2003, right at the end of the messy, experimental Web 1.0 years, ushering in user-friendliness and simplicity with the new Web 2.0 tide. The 2003 digitization privileges digital usability over the proto-digital ethos of writerly remix deployed in the analog version. We might imagine a digital edition of Sentences closer to the ethos of the analog version that is also much less neat and user-friendly than the digital edition we have access to. In this hypothetical effort, five hundred pop-up windows approximating the index card lyrics could populate our screens or a touch screen iteration of Sentences installed in an interactive art space could allow writerly digital users to move and manipulate the ‘cards’ as they would in the analog.

There is an irony at play here—that Sentences in its original analog iteration both lends itself to the ethos of digital collage, digital remix, but also resists actual digitization in a Web 2.0 context. This friction in the phase change between analog and digital for Grenier’s Sentences leaves us to think about what translates between the two and what is lost, on one side or the other. It also leaves us to think about how to get at Grenier’s original impulse with Sentences, “to ‘stop Time’ / [and] ‘destroy the Book,’” in going reverse chronologically from the digital to the analog, seeing Sentences as an analog work with real digital possibilities and implications for the digital (“Guide,” 81). Digital remix has the potential to really up the ante on Grenier’s goal—it would demand, though, that Sentences be truly remixed, put into conversation with other works and released from the unity of its cloth-covered box into the networked, fragmentary “Read/Write” world wide web. This more radical take on digitization insists that the whole of the web be read as the sentences of Sentences, whole, complete, and paratactically movable. In combination, their efforts could really have the effect of “‘stop[ping] Time’” crafting a “perpetual present” in which we writerly readers read and write.

Works Cited

Barthes, Roland. Pleasure of the Text. Notting Hill Editions, 2012.

——S/Z. Translated by Richard Miller, Cape, 1975.

Gold, Herbert. “Vladimir Nabokov, The Art of Fiction No. 40.” The Paris Review, 12 June 2017, www.theparisreview.org/interviews/4310/vladimir-nabokov-the-art-of-fiction-no-40-vladimir-nabokov.

Grenier, Robert. Sentences. Whale Cloth Press, 1978.

—— Sentences. Whale Cloth Press. 2003. www.whalecloth.org/grenier/sentences_.htm

——“Guide to Histories of Making/Production of RG Works 1971 - 1997,” M1082. Dept. of

Special Collections, Stanford University Libraries, Stanford, Calif.

——“Letter to Burroughs Mitchell.” 19 Oct. 1976. Robert Grenier Papers, M1082, TS. Box 4,

Dept. of Special Collections, Stanford Libraries, CA

Kellogg, Carolyn. “Publishing from the Grave, Michael Crichton Style.” Los Angeles Times, Los Angeles Times, 2009, latimesblogs.latimes.com/jacketcopy/2009/11/michael-crichton.html.

Lessig, Lawrence. Remix: Making Art and Commerce Thrive in the Hybrid Economy. Penguin Books, 2009.

Montfort, Nick, and Zuzana Husárová. “Shuffle Literature and the Hand of Fate.” Electronic Book Review, 5 Aug. 2012, pp. 1–17.

Silliman, Ron. “Sentences.” Silliman’s Blog, 17 Jan. 2003, ronsilliman.blogspot.com/2003/01/after-berkeley-robert-grenier-taught.html.

Stephens, Paul. “‘Really ‘Reading In’’: A Media-Archival History of Robert Grenier’s Sentences.” American Literary History, vol. 30, no. 2, 2018, pp. 278–303., doi:10.1093/alh/ajy012.

Cite this article

Schnitzler, Carly. "From Analog Shuffle to Digital Remix: Translating Robert Grenier’s Sentences" Electronic Book Review, 6 December 2020, https://doi.org/10.7273/xpaf-pe03