From Datarama to Dadarama: What Electronic Literature Can Teach Us on a Virtual Conference’s Rendering of Perspective.

On this first Sunday in July 2023, as the Electronic Literature Organization prepares for its meeting in Coimbra, Portugal, we present a set of reflections by four ELO members who co-organized this Organization's 2021 conference fully virtual conference, titled "Platform (Post?) Pandemic." What we have is an insightful critique of platform conferencing. The concepts of datarama turned dadarama offer a refreshingly literary way of reorienting the discourse of the ELO's annual conference.

This article is a reflection on our experiences with co-organizing the Electronic Literature Organization’s (ELO) yearly global conference in 2021, entitled “Platform (Post?) Pandemics”, which was fully virtual due to the Covid-19 pandemic.1 The article will be focused on how to understand the conference through critical data studies and will propose applying poetics and techniques from electronic literature to develop qualitative interpretations. The conference presented a wide range of literary performances, exhibitions, workshops, presentations of academic papers, and discussions that in different ways addressed (as stated in the call) how with “social media, apps, search engines and targeted advertisements, platformization has become increasingly dominant in digital media,” and how during the COVID-19 pandemic, “platforms have entered into our most private and intimate spaces, raising questions about surveillance, capture, and who’s reading our reading and writing.” Considering these socio-technical transformations, the general stipulation of the conference call is that “research into electronic literature” can examine “how we are platforming the future.”

How does electronic literature reflect, “how we are platforming the future”? That the conference itself took place on the video conferencing platform Zoom2 and that (nearly) all presentations and discussions were transcribed and recorded by Zoom, would to many seem like a unique opportunity to perform a sort of statistical “distant reading” (Moretti) of one of electronic literature’s most central paratexts: the discourse of its annual conference. Such approaches have also been conducted by others (Anderson and Willard; Eichmann-Kalwara et al.); however, rather than merely examining what digital methods might reveal about ELO and electronic literature’s take on the conference theme, this article aims to present an understanding of what a conference becomes when formatted into a video conferencing platform. From our initial data studies of the transcripts, we found a lack of results that contributed further to the knowledge we already had after attending the conference, which made us rethink our approach. We want to present how a platform sees and senses us (the community of electronic literature, and users of the platform); that is, how it makes sense, rather than what sense it makes. In this way, we aim to move beyond predictable results and continue the effort from the conference of exploring platforms, their algorithmic techniques, and data processing, through electronic literature.

We see our hands-on experiences of organizing the virtual conference and our attempts to read the conference data from a distance as starting points for a series of reflections. Firstly, we will briefly present the conference. If what people say at a conference might be considered as the textual body of a conference, then the investigation of a platformed view of the conference makes us aware of the many paratexts that are part of a conference. We pursue these paratexts as outsets for a critical study of them as data and argue that a view of the conference through the prism of data can be conceptualized as what we tentatively call a datarama – an attempt to, through data, create an all-encompassing view of the conference, comparable to e.g., a distant reading of the conference. If former visual and architectural media technologies have provided other all-encompassing perspectives on reality such as the panorama, then what is particular for this datafied view?

Consequently, we turn our attention towards the iterative processes of translation involved in rendering this datarama. That is, how the conference needs to pass through a series of translations before proceeding to our eyes; for instance, how processes of textual encodings from sound to text serve as one of these passage points. What exactly are these translations, what is it they render, and what may we learn from them? Our experience is that in the datarama numerous translations between different formats take place where the perspective is constantly rendered. We focus on how these decision-making processes which couple data management and interpretation include, reject, and reflect existing cultural and linguistic practices.

Thirdly, we reflect further on the kinds of literacies involved in the translations. How does one make sense of the conference datarama? We describe our experiences with digital methods, and how our work provides an opportunity to map the different layers of literacy in the datarama. Literacy is often used in relation to the digital, the computational and data, but what does it mean? How does it relate to other understandings of ‘literacy’? And what literacies occur in the datarama? Following media critical traditions from electronic literature, we underline that literacy involves not only “know-how” skills, but also a critical and tactical implementation of such skills, as well as an awareness of what knowledge is being reinforced in these processes.

Finally, we ask ourselves if the datarama, as a rendered perspective on the conference can be presented as an electronic literary perspective? If, as stated in the conference call, “Electronic Literature’s history of developing independent, purpose-specific platforms” is challenged by commercial platforms that “are often closed formats with largely rigid templates for ‘content’”, then where does it leave electronic literature? What types of literature can one write with a platform perspective – or, with a datarama?

Hence, we conclude by moving from data analysis to data creation in a literary mode, moving from a datarama to what we will call a dadarama. We generate a series of poems inspired by approaches to natural language processing, such as those of Allison Parrish, and others in the field of electronic literature. Where data normally is presented and perceived as becoming intelligible through Machine Learning we discover a different reality through electronic literary approaches: A dadarama. In other words, we stipulate that Data may become Dada through ML processes.

Through this series of reflections, we aim to approach critical data studies as an aesthetic process of sensemaking, which combines what data analysis can make us see with how the platform produces data and text – or, to present a literary perspective on what the platform is as a technical apparatus. Although the apparatus according to Michel Foucault reflects an assemblage of “discourses, institutions, architectural forms, regulatory decisions, laws, administrative measures, scientific statements, philosophical, moral and philanthropic propositions,” (Foucault and Gordon 194) our ultimate aim is not to provide a full apparatus analysis but to tentatively suggest how a literary approach might produce insights into the sense-making processes of a platformed conference, how a perspective on the conference is rendered by the platform(s).

We will, however, begin with some contextual background on how this particular ELO conference came to be.

“Platform (Post?) Pandemic”

Consider the spring of 2021. As indicated in “(Post?)” of the conference title, the pandemic was far from over; and not least the conference’s partners in India were amid the second wave of COVID-19, experiencing a shortage of hospital beds and ventilators, lack of medical personnel, and more in one of the countries that were hit hardest by the pandemic.

Consider platforms, too, and how they became further integrated into people’s lives during the pandemic. In retrospect, it can be perceived as a disruptive moment in platform culture – a point in history where platforms entered all aspects of our lives and homes as the necessary option for education, work, social and cultural life, etc. due to social isolation.

Consider the ELO community. It is not only a community dealing with literature, but also one that offers many theoretical, analytical, and practical understandings of the significance of platforms; what they mean, what they do, how they can be used, etc. Electronic literature is a born-digital art form that historically often has relied on platforms. In the early days, most electronic literature was made using custom-built software and designed its own interface, but later platforms such as the now obsolescent Flash became an important part of both the reading and writing experiences of electronic literature (as displayed in the “After Flash” exhibition at the conference). Today, much electronic literature uses corporate network platforms such as Twitter, Facebook, Google, or Instagram, reaching new audiences of readers and writers, but also critically reflecting the role of platforms, including author-control over the design and presentation, ownership rights, cultural use practices, internal mechanisms of user control, and much more (Flores; Berens).

At this moment in time, the ELO community was, in other words, seeking to develop new formats for electronic literature, rethinking, and experimenting with the many new platforms introduced into people’s lives. Similarly, scholars in the field were also developing new understandings of how platforms function as entertaining, compulsive, or addictive substitutions in people’s lives, but also how they during the pandemic had become an increasing part of the construction of a social and cultural reality in the everyday.

On this background, our initial aim as organizers was to produce a virtual conference in the shadows of the pandemic. Organizing the conference on platforms, however, also allowed us to gather vast amounts of data, predominantly of audio transcripts, that potentially could provide novel insights into the conference as a paratext of electronic literature and the community’s reflections on the conference theme.3 But what kinds of paratexts does a virtual conference produce?

Organizing and archiving a virtual conference

Building on prior experiences with virtual conferences during the pandemic (Salter and Stanfill), a basic challenge for us, as organizers, was how to accommodate a community. To accommodate a community, one cannot simply replace a physical conference with video conferencing (in this case Zoom). The ELO, like many other academic communities by default, operates at a range of different platforms that serve the community in different ways. First and foremost, the ELO is a community of peers, meaning that its annual conference is based on calls, submissions, and reviews by peers. To organize this, the ELO uses the conference platform EasyChair. It is also a community that functions as a social network. As in many professional communities, the informal meetings between its members play an important role in building networks and collaborations, welcoming new scholars, building friendships, and every other cultural practice that ties the community together. The ELO community therefore also operates a channel on Discord, which, along with GatherTown, functioned as separate conference venues during ELO 2021. The ELO is also an art/literature community, meaning it is based on a professional interest in electronic literature, and both exhibitions and performances are an important part of what binds the community together. The conference featured 128 artworks exhibited at different venues and online in 6 curated exhibitions (in an exhibition design made by Jason Nelson) and as part of the conference’s performance program.4

As a particular challenge in the organization of the virtual conference, the ELO is also a community that is spread across six different continents and time zones, and the virtual conference format allowed a very diverse contingent of participants, including people who could not normally afford or set the time aside to travel. Synchronicity and liveness are obvious problems that one must address. Instead of pre-recorded video presentations of papers (sometimes used in virtual conferences operating across time zones), all presenters in the conference track submitted full papers of their presentations available from the conference website (using the content management system Typo3, hosted by Aarhus University), and were asked to give very short presentations. This format would allow time for fuller and deeper discussions – rather than just talking heads. Using Zoom’s cloud recording feature, all sessions were also immediately made available online (on Vimeo, via the ELMCIP Knowledge Base), allowing participants to catch up on sessions that were too early or late for them (the conference was organized from 11 AM to 9 PM UTC to fit as many as possible in Asia, Europe, and the Americas). Furthermore, Zoom cloud recordings come in a variety of file formats: Audio/video file (.MP4), audio only (.M4A), a playlist for playing all individual audio/video files (.M3U), a text record of the chat (.TXT), and a text file of the audio transcription (.VTT) that can be used for subtitles.5

In other words, organizing a virtual conference does not produce one single outcome, but multiple paratexts that in each their way reflect how the community addresses a “Platform (post?) pandemic”. To understand this disruptive moment in platform culture through electronic literature, it is evidently necessary to further study the academic arguments and artistic works that were presented in the exhibitions. Hopefully, the conference will inspire many in the community to do so, and the Zoom recordings may be useful in this, too. However, video conferencing is much more than a mere medium for a conference, and in continuation of the theme of the conference, our question is how the platform constructs a particular perspective on the conference. With particular attention to the audio transcriptions (a total of approximately 70 hours of video calls, and ca. 2.5 million characters of text), the aim in the following is to pursue a critical understanding of the conference data, building on theories that study how data and data-setting reflect a larger cultural history of technological perspective.

The datarama

A basic question for a virtual conference is where it takes place? From one perspective, the conference predominantly took place in Aarhus and Bergen where it was mainly moderated and hosted. As mentioned, speakers and audiences, however, came from six different continents and were sitting in their homes or offices (COVID restrictions permitting). The virtual conference may therefore also be perceived as generated from the more than 250 individual interfaces of the participants – as an individualized mass or multi-perspective controlled by interfaces, software, and platform architecture. All participants attended the conference logged in to the necessary cloud-based platforms, but combined with an individual perspective, i.e., their personal interfaces and platforms (their laptop, their operating system, their browser, their camera, etc.). The conference took place everywhere, but nowhere in particular – or one could say that the ‘view’ from the platform is ‘the’ view that generates the conference’ space.

The construction of an architectural and virtual view from a platform is not a new thing invented by Zoom but reiterates historical mass-mediated utopias like the panorama. The panorama was part of the 19th century pre-cinematic ‘-orama’ media (including the diorama, cyclorama, cosmorama, and myriorama), introduced in major cities in early modern, urban milieus, where the sovereign overview had been lost to the urban mass, commercialized media, bureaucracy, and marketization.6 The panorama has been described as the first commercial visual mass medium constructed as an architecturally controlled virtual view, literately from a building without windows. The viewers are confronted with a view that is bigger than their perspective and the central perspective is substituted by a mass perspective from the platform in the center of the panorama rotunda that they buy a ticket to enter. In this sense, it is a visual training architecture for a new imaginary, which we can call modern, liberalist and capitalist (Oettermann). The panorama is important for Honoré de Balzac’s literary realism as a way of showing and reflecting on the new, mediated perception of the urban reality of Paris. Besides, panoramas were a way of conquering and colonizing the surroundings in the sense that panoramas often portrayed battles and remote places and were used in nationalistic propaganda (Pold).

There are obvious parallels between the panorama and contemporary platforms – as elevated viewpoints (assemblages of interfaces) with opportunities, actions, and insights (Gillespie). However, there are also important differences. In particular, one should pay attention to the staging and production of perspective, and how perspective simultaneously is directed and limited by the architecture; or, put differently, how it is rendered, meaning how it is animated to us and given volume as a causal process (Andersen and Cox).7 As a digital, statistical, semio-capitalist ‘phantasmagoria’, what we might call the ‘datarama’, like the panorama and other “oramas” in the history of media technologies (the diorama, the cyclorama, etc,) hides its conditions from immediate view of its users and contributors, but does so in distinct ways.

Nooscopic translations

In a rendering perspective, the datarama has a “nooscopic” character. Or better said, it is a series of nooscopes related to data translations. By translations, we mean the processes of selection, automated or manual, between the data formats of the conference (e.g., from recorded sound to text, or from text to networks). The nooscope, derived from the Greek words skopein and noos (“to see” and “knowledge”, respectively), is defined by Matteo Pasquinelli and Vladan Joler, kindly borrowing from Leibniz, as “an instrument to navigate the space of knowledge” (Pasquinelli and Joler 1263). Much like the telescope, the nooscope is understood as an instrument of perception and measurement, but in the digital age of machine learning where causation as a general epistemological directionality is replaced by correlations. Pasquinelli and Joler’s nooscope offers a generous analysis of current machine learning processes, including different types of biases, labour practices, and technical shortcomings. Of particular relevance in this context are what they label “dimensionality reduction” and the “undetection of the new”, in part because these two phenomena are inherent not only to machine learning but in general to any data translation, automated or manual.

Dimensionality reduction refers to the practice of minimizing the quantity of variables in a dataset or statistical model to avoid exponential growth. This reduction entails either conflating similar clusters or categories (putting together objects in the same category or vector, if they are minimally different) or even removing certain outliers (ignoring objects that happen too rarely). The notion of dimensionality reduction entails a filtering process which makes some things more visible than others. The associated phenomena of the “undetection of the new” is a nested outcome of reduction: for example, a model trained for a certain type of normalized data, will not be able to recognize data located beyond this reduced grammar. While these phenomena can certainly be tuned, they are an inherent part of any (digital) translation process.

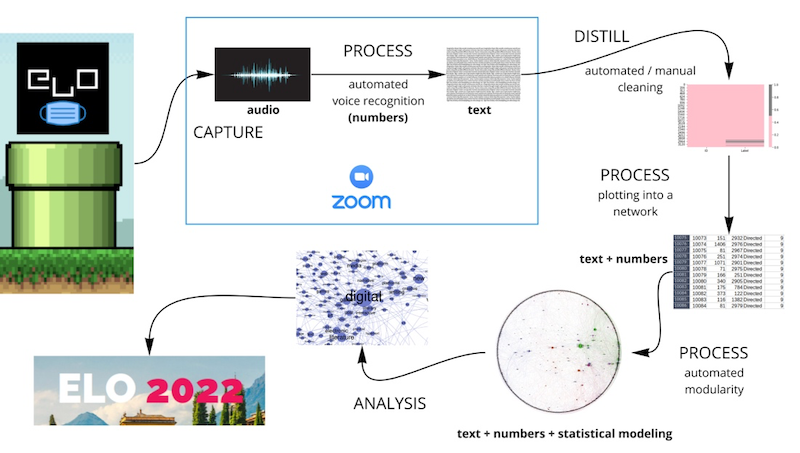

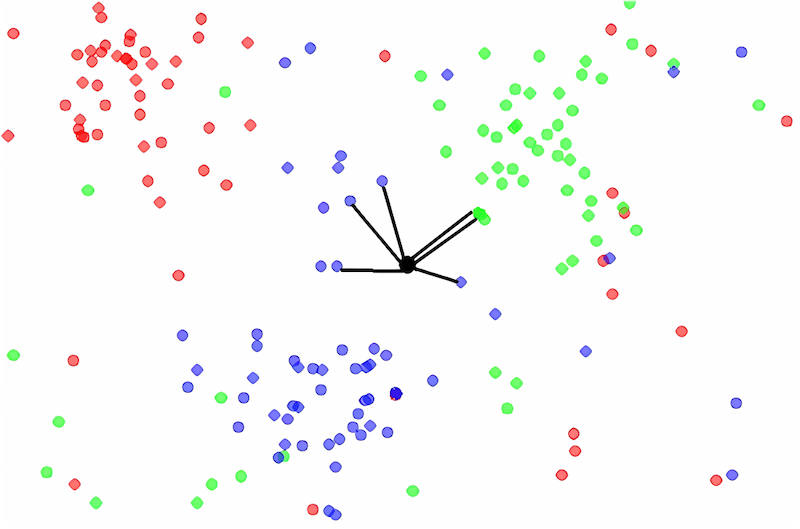

Fully aware of the impossibility of a 1:1 representation of the conference, we designed, with the aid of our student assistants, different approaches to reflect on which data was reduced and which data was brought into the main stage with our own translation processes. More specifically, we a) did a close reading of (parts of) the transcripts, b) used Natural Language Processing (NLP)-derived bigrams (using Python’s Natural Language Tool Kit and Pyvis) to detect the correlation of words (e.g., “electronic” and “literature”), and c) did a word co- occurrence analysis (using Gephi) to visualize the frequency and clusters of co-occurrent selected keywords. In this paper, we focus solely on the findings of the third approach.

While reflecting and working on the transfiguration between the lived experience (as one of the many paratexts) of the conference and the three different distillation processes, used to render the conference visible, we observed two important implications.

First, a process of distillation or dimensionality reduction takes place, inevitably, in each step of the process. In every instance of decoding (e.g., voice to text) and encoding (e.g., text to numbers) some data is made more visible than others. Through either an automated or an agential decision-making process, some data is assigned relevance, and some data is left behind. While this is perhaps expected or well known, working with the living phenomena (that is, the conference) allowed us to observe the technical granularity that lies behind the more grandiose datarama. That is, more than a 1:1 nooscope between the lived experience of the conference and the datafied reading of it, our observation sheds light on the many moments where viewpoints were attuned through the technical organization, and where dimensions were reduced or repurposed.

Second, that our point of departure, the ‘raw’ data from the conference, was already an output. Our .VTT files (the text files of the audio transcriptions) were packed following a technical perspective that filters some types of data and is naïve about other types. Presentations, replies, questions, and every significant or menial conversation happening in between, that is, the lived experience of the conference as it happened through Zoom, were captured through the specific prism of the already known. The most obvious example of this is how novel wording or non-standard English pronunciation is simply not captured when translating voices to data. There is a note to make here, on how a pronunciation preference was naively already taking place in the early data translation processes, which misspelled (i.e., incorrectly encoded) many non-native English pronunciations. For example, turning “panel” into “funnel”, “gender” into (the non-existent word) “dunder” and “hermeneutics” into “have an artist”. In this sense, Zoom’s transcription includes an Anglo-American bias that made it misinterpret many non-native English accents and all other languages than English (in our case). What we want to stress here is that even before starting to make sense of our available data, the data had been made sense of through specific translations in the software. These elementary translations are also partially black-boxed, as they happen to be a service provided through Zoom. We can speculate that the audio data, alongside its metadata (e.g., the person recognized as a speaker), is automatically encoded through machine learning for voice recognition. This apparently seamless translation, however, is already mediated by a quantification process, where audio streams are fed into a statistically based recognition process which turns audio into numerical approximations into text. That is, our ‘raw’ material for the conference data has been twice distilled (from audio to numbers to text) before we even start our own translation processes.

Our translations

Delving into the notion of dimensionality reduction, we were then confronted with the question of what was noise in our data. The translation of international and phatic conversations from the conference resulted in a messy transcription: names were incorrectly interpreted, niche or conceptual terms were not recognized, and non-English phrasing was weirdly deciphered as random words. Even the name of the organization behind the conference, ELO, was translated into a plethora of, sometimes risible, wordings, like “yellow” or “eel”. A typical approach from data analytics would require us to follow some standard procedures to clean the data, like for example, removing ‘stopwords’ (words that appear in many instances but are not significant, such as “the”). But given the lively nature of our data, we were forced to revisit what takes the place of a stopword in this scenario, and what sort of meaning would be removed. “Right“, for example, is a word that was used in significantly different ways (“bottom right button“,“being right“,“right?”), but which one of them can be tagged as meaningful in the spoken context of our conference? Indeed, “right” could in some instances be interpreted as a way to negotiate through a phatic language function the sense of being at a conference even if sitting in one’s living room behind a laptop (“right?”). The vocal mode of ELO made us question what we will probably be less hesitant to remove from a written text.

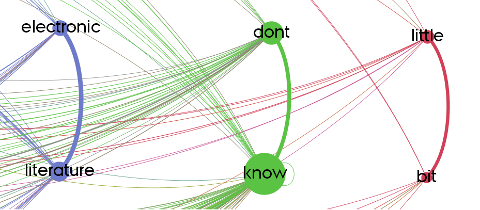

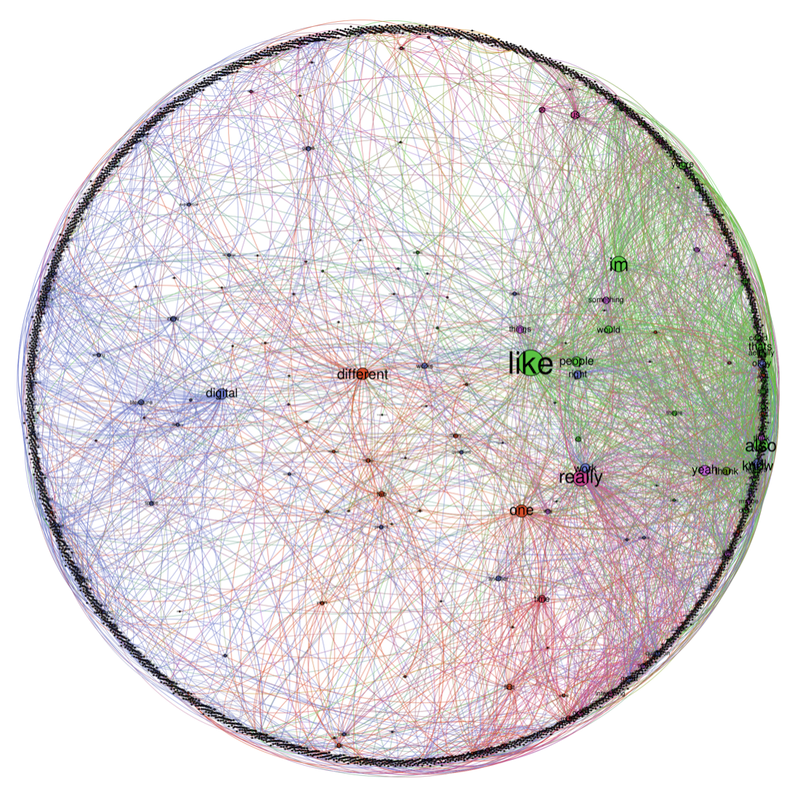

We decided to keep most of the words and removed only standard stopwords (“the”, “is”, etc.) while building a co-occurrence network. The network displays 1n co-occurrence, i.e., it connects words with their immediate neighbor, bounded by sentences. This allowed us to make visible strong relations between concomitant word-pairs used in a sentence. Unlike vector-based techniques (or similar attempts like topic modelling) which aim to extract core themes within a corpus, we were interested in revealing the spoken nature of the data. Word co-occurrence allowed us to generate word pairs which, to some degree, maintained the temporality and continuity of the spoken word. The most common word associations in this network indeed reflect the fluidity and informal disposition of a dialogue, more than the categorical statements of a published paper: “don’t know”, “little bit”, “really different”.

The graph above [FIG 4 Planet ELO], one of the many representations of the platform conference according to a platform, holds the promises of the datarama, an all-encompassing mass view. It is tempting to declare that this bi-gram network is a faithful representation of the conference, after all, it includes and displays every significant word. Such is the promise of the datarama when it ignores its production. Our approach then tried to turn the attention from the “sites of projection” to the “sites of production” (Latour), away from the all-encompassing results of the datarama, and towards the moments where data translations harbor their own nooscopes.

When managing (big and small) data we, as humanists, artists, and social scientists, rely in some way or another on the tools of data analytics. This is a critique highlighted by Johanna Drucker, for whom there is not only a need to understand the consequences of using these tools for humanities concerns, but also a need to imagine and develop alternative tools that stem from the inquiries between social sciences, arts, and humanities. According to Drucker, such approaches to data should be able to integrate the complexity of constructivist readings, as well as imagine representations that embrace ambiguity and uncertainty (Drucker). Our graph follows such a field path: rather than producing a panoramic representation, it seeks to embrace translations and pattern recognition as cultural practices (Rieder) and to reflect their aesthetic, political and epistemological consequences.

Drucker’s observation highlights how the rendering of perspective in the datarama, i.e., our translations of data and experiences with the software’s technical translations, begets a particular ‘literacy’; or rather, a range of ‘literacies’, and we would like to pause for a moment, to reflect on our experiences in working with the nooscopic translations.

Datarama literacies

Data and digital literacies seem to be core concepts in educational discussions (from primary school to higher education), focusing on the use of digital tools, the ability to synthesize and evaluate information, problem-solving and, in general, becomingfamiliar with computationally based processes. But what kind of literacy does making sense of the former translation processes entail? How does the datarama relate more specifically to the process of reading and writing?

Besides a general textual literacy that allowed us to read the transcripts, working in the datarama clearly indicated a need to realize that data does not appear from nowhere, but from somewhere and someone. It depends on sensors (users’ microphones and cameras), it depends on a complex setup and a network of interfaces, it is accessible in different formats (.VTT, .MP4, .TXT, etc.) which have a platform politics of their own, and it is collected, scraped and cleaned (for stop words, for instance). In other words, this data literacy includes first and foremost the competence to both tactically and critically apply methods of collecting and cleaning data.

But it also involves a new kind of visualization literacy. Reading the transcripts as a network textual analysis (e.g., detecting word correlations or concurrences) very often involves the use of visualizations. In our case, we mostly used Gephi, which in many ways may be compared to a larger turn to dashboards in contemporary data analysis.

As suggested by Cowley et al., the dashboard puts into focus the data in use “at the point of decision making, where it can be acted upon” (Cowley et al. 35). In other words, it reflects an epistemological condition in which data has an indexical and also a live quality. We do not need to listen in depth and qualitatively assess all the conference presentations to get a deep insight into the conference; the visualizations will provide us with a ‘here and now’ index of what the conference was about. For instance, the word “platform” was used extensively – 845 times during the conference, compared to for example “literature” which was used 721 times, or that most “questions” are (occur with) “great”. This allows us to not only see the discourse (i.e., visualization literacy), but also provides us with a managerial advantage. Although we did not generate live visualizations as the conference was happening, ideally the visualization of the conference discourse signals something – such as hidden meanings or preferences in the discourse – that the ‘literate’ can act upon. For instance, we could have displayed if certain words or relations of concepts are trending, and decide to oppose, problematize, or take advantage of this.

This kind of managerial visualization literacy is often picked up by digital humanities scholars. At many faculties of humanities, it is becoming increasingly common to offer students and researchers courses in data visualization. Often these courses also offer another type of literacy. For instance, they often include lessons in R, and Python distributions like Anaconda that not only provide the future data scientist with the tools to generate and manage the dashboard, but also with a powerful tool to think with: they focus on the affordances of new digital methods, and the ability to imagine possible other types of insight. As such, data literacy also relates to broader discussions of “computational thinking” within education (Wing).

One example of how to ‘think’ with data would be the application of the so-called word to vectors technique, which we applied in our inquiries into the conference data and which we will use in our poetic experiments below. Word to vectors builds on the idea that a word’s contextual meaning – which we would otherwise assume is an exclusively human capacity to decipher – can be solved by algebra. Representing meaning through algebra allows us to see a new relationality between words that are otherwise not clear to us.

Without entering the techniques in depth, the method by and large builds on extracting, translating or transforming a word into a series of numbers or coordinates, based on its contextual distance. Say – as an imagined example from our text corpus – we could find that “posthumanism” is close to “cool” and to “quite new”; and that “postmodernism” is less close to “cool”, and also to “quite old,” it would generate the following result:

“Postmodernism” – not so cool – quite old

“Posthumanism” – very cool – quite new

We might also find that some relations are the same; say, that “postmodernism” relates to “posthumanism”, the same way that “the animated GIF”, relates to “Zoom”. That is, some words are related to each other, when thought of as vectors, even if this relationship does not exist in their traditional associations. However, it has often been argued that such representations of the world not only show existing relations but also reinforce them – e.g., that “Man is to Computer Programmer as “Woman is to Homemaker” (Bolukbasi et al.). In other words, this ability to think with computation is by no means neutral: it is deeply intertwined with the construction of identities, or other social constructions.

These literacies are all examples of what it involves to render the datarama – to make a process of distillation and dimensionality reduction take place, step-by-step, and what it implies to make an apparatus of decoding and encoding operational. Like former literacies, they also work across multiple scales. As highlighted by Colin Lankshear and Michele Knobel, literacy is not a uniform concept, but one that taps into different scholarly traditions, with different epistemic interests (Lankshear and Knobel).

Conventionally, literacy functions as an indicator of a nation’s educational level, and hence its potential productivity and economic growth. It traditionally refers to the reading and writing of words but should also be considered in an expanded context of text. There are in other words many forms of literacies: visual literacy, media literacy, data literacy, and digital literacy. With this, it also becomes evident that the question of literacy is not only a question of education but also one of culture and identity: social identity is shaped by one’s ability to take part in a textual, visual, media or other discourse. Being able to not only take part in a discourse, but also realize how one is written by the discourse then becomes another kind of literacy, which one might associate with e.g., Paolo Freire’s notion of a “pedagogy of the oppressed”: literacy as a process of liberation, and a distinct marker of an ability to question and shape civic society (Freire). Furthermore, literacy should also be related to work within the field of electronic literature such as John Cayley and Daniel Howe’s The Readers Project in which they explore literacy and how reading and readers are reconfigured by contemporary platforms (Cayley and Howe). What is of particular interest to us is this latter understanding of literacy, which often tends to disappear in favor of critiques of, for instance, the data setting or computational thinking as biased constructs. What we want to suggest is that electronic literature may play an additional role in questioning and experimenting with the hidden grounds of translation processes on which meaning occurs, the sense-making of the datarama. In other words, in liberating oneself from the strains of computational thinking and other digital literacies.

In line with Freire’s pedagogy (but refraining from details), this liberation, which we ultimately propose relates to the role of electronic literature, involves a Marxist dimension. Platforms like Zoom, belong to a new moment in capitalism which calls for new ways of learning how to liberate oneself from their oppression, new ways of relating to them, and new conditions for these relations.8 Arguably, platforms impose logic and only adapt to certain classes of users in their rendering of perspective. This, we see for instance in the translations and glitches in the text encodings; but one may, in a much broader perspective, question how we as users are considered entities that are ‘mastered’ by the platforms, and how we in our use reaffirm them in their rendering of perspective? Such knowledge of logic and mastering remain the property of the platform (‘oppressor’) and are difficult to comprehend, but a literary approach might allow for a space for us to experience how meaning and ultimately, we, as users, are produced and mastered. That is, it might de-construct (or ‘de-render’) the datarama’s rendering of perspective and allow for a more poetic, human interaction with the platform. For this, we turn to the dadarama.

Platform poetry | Dadarama

We want to begin this literary approach to data with an example – an example of how vectorization leads to new kinds of poetic encounters with the conference, or what we call ‘platform poetry’.

Platform poetry consists of (1) a title that is also a query that generates a poem and (2) a poem that takes the form of an array, that is, a list of data points that we received as output for the query. In this instance, we used a K-Nearest Neighbors model that was trained on the unedited transcripts from the conference, as we explain below. With this approach, we have created a small selection of platform poems that meditate on the relation between vectors, knowledge, and literature. As an example:9

time zone [‘time zone’, ‘the time zone’, ‘my comfort zone’, ‘this gray zone’, ‘real difference’, ‘some version’, ‘that version’, ‘that difference’, ‘this difference’, ‘this version’, ‘what difference’, ‘less time’]

To understand how these poems came about, let us look at the software used to generate them. We used a K-Nearest Neighbors model implemented in the natural language processing framework spaCy, based on code by digital poet Allison Parrish (“Understanding Word Vectors”). Such a model belongs to the machine learning subcategory of AI. Instead of tediously programming computers to do certain tasks by explicating each step, machine learning works by getting the computer to model a dataset, in other words, machine learning is popularly known as programming-by-example. Based on the measurement of and statistical operation on myriad data points, a K-Nearest Neighbor model is optimized to look for the ‘closest’, so to speak, vectors in the dataset to a given input. Remember the vector spaces mentioned above: word vectors that are close in vector space are also – in many cases – semantically connected. Thus, using a K-Nearest Neighbors model, we can input any string of words as a query to the dataset and in return we will get a selection of strings of letters (i.e., words or sentences) that are ‘close’ to the input. Note that the input does not need to be something that was already present in the training data, whereas the output will always only consist of vectors from the dataset, i.e., the title of the poem resides outside the conference data, but the lines of the poem are taken directly from their original spoken form (that is, after a series of translations).

The above poem “time zone”, is then, an array of short sentences whose vectors neighbour the same coordinates as the vector of the input value “time zone”. Another example is querying the dataset with the string ‘a vectorized poem’, the result is a list of the most similar data points in the conference transcript, resulting in a conspicuously self-referential reflection:

a vectorized poem [‘a jpeg’, ‘a quote’, ‘a quotation’, ‘a click’, ‘a poem’, ‘a very poemy poem’, ‘this poem’, ‘this pdf’, ‘these quotes’]

Word vectors and other forms of natural language processing are usually thought of as tools that can help ‘mine’ a text for answers to a hypothesis. Arguably, they are useful for that, but they are also poetic and embracing the poetic nature of computational outputs may potentially reveal other insights.

this is electronic literature [‘this electronic literature’, ‘as much electronic literature’, ‘that electronic literature’, ‘what electronic literature’, ‘how electronic literature’, ‘both electronic literature’, ‘so electronic literature’, ‘an electronic literature’, ‘also electronic literature’, ‘not necessarily electronic literature’, ‘just a tool’]

“Language models can only write poetry“ Allison Parrish claims. In saying this, Parrish construes poetry as “a material, which can result from any process (whether conventional composition, free-writing, or tinkering with language models)” (“Language Models Can Only Write Poetry”). Although Parrish mainly discusses generative large language models such as OpenAI’s GPTs, we can infer that K-Nearest Neighbors also belong to poetry-producing machinery, given the breadth of processes that Parrish mentions. Thus, in contrast to Irving John Good, who in the early days of AI famously speculated that writing poetry would be a characteristic of what he called “ultraintelligent machines“ (Good), Parrish suggests that generating poetry is an easy task: make the machine generate language.

Despite the seeming dismissal of the value of poetry, Parrish is not saying that we should disregard our poetic inclinations or that any scrambled language will be equally poetically vibrant, but that we should understand the computational outputs in terms of their materiality, that is, in dialogue with the conditions of their generation. This material understanding of poetry can also be characterized as a Dadaist approach to poetry.

vectors are dada [‘a Bo alphabet Omega genders’, ‘vectors’, ‘viruses’, ‘good viruses’, ‘yo ho ho’, ‘hi everyone’, ‘hi folks’, ‘hi everybody’, ‘Miss K’, ‘the second hon hon’]

In Tristan Tzara’s famous meta-poem from 1920, “To make a Dadaist poem”, Tzara instructs the reader to take a newspaper article, cut the article up into individual words, place the words in a bag, shake it gently, and then compose a poem by taking out one word at a time, placing them in the exact order in which they left the bag.

To make a Dadaist poem: Take a newspaper. Take some scissors. Choose from this paper an article of the length you want to make your poem. Cut out the article. Then cut out each of the words that make up this article and put them in a bag. Shake it gently. Then take out the scraps one after the other in the order in which they left the bag. Copy conscientiously. The poem will resemble you. And here you are a writer, infinitely original and endowed with a sensibility that _is charming though beyond the understanding of the vulgar. (Quoted from Cramer 6)

Tzara’s meta-poem predates the digital computer by more than two decades, but it is often brought up as a provisional example of text generation, since, as Florian Cramer notes, “[t]he poem is effectively an algorithm, a piece of software which may as well be written as a computer program” (Cramer 6). Thus, Tzara’s poem prefigures aspects of data-based text generation, most notably that the outputs cannot deviate from the corpus; like the vectorized poems, Tzara’s resulting text will reflect a statistical rendition of the article that is chosen to be cut up, which is to say, of the dataset. However, there are also significant differences between Tzara’s meta-poem and our platformed poems.

Whereas Tzara’s poem would, if we executed the instructions, lead to an output governed by random probability distributions of individual words in the article, the outputs of our K-Nearest Neighbors model are based on systematically designed distributions that approximate, or at least claim to approximate, a semantic mapping of the dataset. One of Cramer’s arguments in his reading of Tzara is that we do not actually have to do what the poem says to appreciate it: the act of cutting up newspapers and scrambling their contents would not add much to our understanding of Tzara’s work. In other words, it is mainly a conceptual piece.

Contrarily, in the case of our platform poems, the execution of the system is absolutely central. No amount of conceptual consideration of the idea of a K-Nearest Neighbors model would lead to the emergence of poems like the ones we here present. Even though each case construes poetry as a material, they differ in terms of the conditions under which that material came into being. In Tzara’s work, the concept trumps the execution and, by extension, the output, whereas in our case, concept, execution, and output must be considered together to appreciate the platform poems.

And so, it seems that a vector is not a bag, it is much more than that, but perhaps at least some vectors are still dada, nonetheless. Were we to execute Tzara’s instructions, the resulting poem would, at its most basic material layer, reflect the cloth-to-paper interactions of bags and cut-up articles. In much the same way, but under drastically different material circumstances, our platform poems reflect the complex processes of translation, literacy and vectorization mentioned above. We are mainly dealing with a difference in terms of complexity, which in this case also becomes a difference in the incitement to execute.

this is poetic knowledge [‘this knowledge’, ‘that insight’, ‘very little knowledge’, ‘some insight’, ‘a little bit more detail’, ‘a predictable way’, ‘a very nice metaphor’, ‘a simple thing’, ‘a real metaphor’, ‘a simple it’]

The materialization of language, in other words, not only makes the outputs from computers poetic, but it also enables poetry to become a way of knowing that reflects the rendering that took part in the emergence of the poems. The poems (the queries of which differ only in terms of conjugation), for instance, help us question how gender was discussed at the conference in quite different ways than, say, a sentiment analysis or word cloud. If, as Serge Bouchardon and Ariane Mayer argue, the experience of reading poetry is characterized by instantaneity, meaning that there is no clear sequence in which the events in the poem unfold and by extension that a poem ultimately expresses an instant rather than a sequence, and multiplicity, meaning that one poem can contain multiple voices as well as multiple kinds of sensory experiences all at once, then these poems provide equally instantaneous and multiplicious insight. Instantaneous because each line in the poems could come from any point in the conference, without a clear temporal direction, and multiplicious because each line could originate from one or more unique pronouncers with no clear indication of their origin.

a gendered platform [‘Artistic patterns from a global pandemic experience.’, ‘Minimal technical affordances.’, ‘As a platform for marginalized voices.’, ‘Many interesting aspects relating to gender, bodies and globalisation.’, ‘So they are inflected by social media and mobile practices.’, ‘During platform culture and online life.’, ‘We need to unpack all the platform ideologies.’]

Thus, the poem above was generated from the input “a gendered platform” and takes that same phrase as its title. It reads like a to-do list to address issues of gender in computational culture, or perhaps as a transcript of a slightly messy academic discussion, whereas the other poem below, “a platformed gender”, provides less academically charged discourse and reads more like a series of moments in which the problematic of gender exists in the underbelly, so to speak, of the output.

a platformed gender [‘Irate protesters appeared carrying signs exoticism racism appropriation imperialism and murder.’, ‘Utopianism.’, ‘No politics.’, ‘Moral soapbox’, ‘Last lucille pareto stuff palomas’, ‘I understand regretting life choices’, ‘Oh gotcha’, ‘Soren you’re unmuted <3’, ‘Sorry media fandom.’, ‘Claustrophobia, sorry’, ‘Congratulations all! :-D’]

Conclusion

So, what do we know about ELO 2021, organized, and attended by a community spread across the entire globe? Though the conference accepted papers on all kinds of topics related to electronic literature, data also reveals that the word “platform” was used extensively (845 times during the conference). Also, many platform-critical artworks were featured in the exhibitions and performances, many of them relating to platform culture (e.g., social media). Examples include, for instance, works by Ben Grosser, Mark Sample, Giselle Beiguelman, Alexandra Saum-Pasqual, Annie Abrahams, Atom-r, Salyer + Schaag, Jörg Piringer, Ana Gago & Diogo Marques, Jody Zellen and Bilal Mohamed. There were also ongoing discussions of historical platforms including how to preserve, exhibit and explore them. For instance, discussions of the exhibition “After Flash”, the platforms Flash and Storyspace, The NEXT initiative10, and several post-digital returns to historical genres such as net-art and hypertext. Also, the potential of exploring digital folk and vernacular electronic literature and finding new writers and readers of electronic literature among the massive audiences of commercial platforms were discussed. It is safe to say that “platform” was a strong theme, but it is also notable that it points to a diversity of agendas, topics, and approaches.

But beyond the numbers, participation, and overarching topic of the platform, how does this platform conference render perspective? How does it make data and make sense out of the data? Our approach provided two trajectories for answering these questions: first, the potentials and issues of the datarama, and second, the possibility of a radically different reading as a dadarama. In the first instance, we followed some of the transfigurations data makes and takes.

Still, under a relatively positivist, quantitative data management approach, we generated a data-oramic vision of the conference, albeit with our focus not on the promise of an all-encompassing representation, but instead on the technical and managerial processes that guide such translations. Our analysis pushed us to rethink which type of literacy is at play in the understanding of these translations. Such literacy, we argue, is not only related to the know-how of technical malleability to build representations but oriented towards the creative and generative sense-making processes that such translations permit.

With the dadarama and dada literacy, we turn towards the role of electronic literature in the questioning of data translations. Written from and with a platform perspective, yet not guided by the representational modes of the datarama, we produced a series of vector-based platform poems, which we present as poetic encounters. These are examples of sense-making from what we have called a dadarama, an alternative reading and writing of the conference data, that uses somewhat traditional data and techniques but for a poetic production in the line of Tzara’s dadaist poems.

We have studied a virtual conference on electronic literature and its relations to platforms, ELO 2021, through the data produced by the platforms it was held through, especially Zoom. Participating (and co-organizing) the conference, we had a clear understanding, that the conference as a common, collaborative endeavor, including its many papers, workshops, discussions, exhibitions, and performances, marked a pivotal and potentially disruptive moment in platform culture after more than one year of pandemic lockdown, and as mentioned above we can point to several different ways of exploring platforms and data at the conference. Inspired by this, we started exploring all the data through different data studies processes as described above, but rather than giving us interesting outputs directly, the results we got, such as the high frequency of words like “right” (1086 mentions), led to new questions about how participants of the conference negotiated the very fact that they were participating in a conference that happened on platforms while also being about platforms and electronic literature. This raised discussions about how platformization influences our language – obviously, participants say “platform” often (845 mentions) and we tried to find interesting correlations of words and got outputs such as “electronic” and “literature”, however, most of these findings were banal and predictable as the finding that people tend to say “electronic literature” often at an ELO conference. This led to the discussions of how platforms render language and the conference – how it is co-produced by the rhetorical situation created by the technical setting and how platforms translate the conference into data, including mistranslations such as “ELO” becoming “yellow”.

Consequently, we ended up analyzing not only the data but also the processing of platform data and how understanding this processing allowed for new and expressive ways of exploring the data. Eventually, this led us to a platform poetry, inspired by electronic literature and borrowing code and strategies from Alison Parrish and Tristan Tzara. Thus, we move from the datarama as a way of trying to understand data sensing in relation to the conference to dadarama as a way to write with the conference, to make it expressive and potentially get beyond the banal and predictable that we found with more traditional tools.

Jill Walker Rettberg points to failed predictions in machine learning as a relevant focus for qualitative research to get beyond the boring and predictable results that digital humanities are often criticized for. She argues instead for “using machine learning against the grain” to “develop machine learning methodologies that support the epistemologies of qualitative research” and points to critical and artistic ways of using machine learning (J. W. Rettberg 4). Using electronic literature as a way to experiment with and explore data processing and machine learning builds on a long tradition of generative literature (S. Rettberg), which is becoming even more relevant with current developments in ML/AI. We hope to have demonstrated that electronic literature might be relevant as a resource for the development of qualitative machine-learning methodologies and that data produced by a virtual conference on Zoom, too, can be explored as electronic literature. If data normally is presented and perceived as becoming intelligible through machine learning, we discover a different perspective through electronic literary approaches.

Whereas the datarama tends to present obvious results that could potentially make sense in a dashboard to quickly overview and ‘control’ the conference, the dadarama platform poetry presents a more evocative and less controlled perspective. In machine learning, data is generally cut up and collated through statistical methods, hence Dada platform poems might be the literary equivalent of developing literacy.

what is a conference? [‘It is a summary of what I have presented, and these are my references so thanks very much.’,

‘So.’, ‘Well.’,

‘So okay’, ‘So.’,

‘So.’,

‘So.’,

‘So.’,

‘Excellent!’]

References:

Andersen, Christian Ulrik, and Geoff Cox. “Rendering Research“ APRJA 11, 1 (2022): 4-9. Print. https://doi.org/10.7146/aprja.v11i1.134302

Anderson, Mark W. R., and David Millard. “Hypertext’s Meta-History: Documenting in-Conference Citations, Authors and Keyword Data, 1987-2021.” In Proceedings of the 33rd ACM Conference on Hypertext and Social Media, 96–106. Barcelona Spain: ACM, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1145/3511095.3531271.

Berens, Kathi Inman. “Third Generation Electronic Literature and Artisanal Interfaces: Resistance in the Materials.“ ebr [electronic book review] 2019.5 May (2019). Print. http://electronicbookreview.com/essay/third-generation-electronic-literature-and-artisanal-interfaces-resistance-in-the-materials/.

Bolukbasi, Tolga, Kai-Wei Chang, James Zou, Venkatesh Saligrama, and Adam Kalai. “Man Is to Computer Programmer as Woman Is to Homemaker? Debiasing Word Embeddings.” ArXiv, July 21, 2016. http://arxiv.org/abs/1607.06520.

Cayley, John, and Daniel C. Howe. “The Readers Project“. 2009-. <http://thereadersproject.org/>.

Cowley, Robert, et al. “Forum : Resilience & Design (Preprint).“ Resilience : International Policies, Practices and Discourses 6.1 (2018): 1-34. Print. https://wrap.warwick.ac.uk/90326/.

Cramer, Florian. “Concepts, Notations, Software, Art.“ Seminar for Allegmeine und Vergleischende Literaturwissenschaft (2002). Print. http://cramer.pleintekst.nl/all/conceptnotationssoftwareart/conceptsnotationssoftwareart.pdf.

Drucker, Johanna. “Humanities Approaches to Graphical Display.“ Digital Humanities Quarterly 005.1 (2011). Print. http://www.digitalhumanities.org/dhq/vol/5/1/000091/000091.html.

Eichmann-Kalwara, Nickoal, Jeana Jorgensen, and Scott B. Weingart. “Representation at Digital Humanities Conferences (2000–2015).” Bodies of Information: Intersectional Feminism and the Digital Humanities, edited by Elizabeth Losh and Jacqueline Wernimont, University of Minnesota Press, 2018, pp. 72–92. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.5749/j.ctv9hj9r9.9.

Flores, Leonardo. “Third Generation Electronic Literature.“ ebr [electronic book review] 2019.7 April (2019). Print. http://electronicbookreview.com/essay/third-generation-electronic-literature/.

Foucault, Michel, and Colin Gordon. “The Confession of the Flesh.“ Power/Knowledge: Selected Interviews and Other Writings, 1972/1977. Brighton, UK: Harvester Press, 1980. Print.

Freire, Paulo. Pedagogy of the Oppressed. Trans. Bergman Ramos, Myra: Bloomsbury, 2014. Print.

Gillespie, Tarleton. “The Politics of ‘Platforms’.“ New Media & Society 12.3 (2010): 347-64. Print. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/1461444809342738. 10.1177/1461444809342738.

Good, Irving John. “Speculations Concerning the First Ultraintelligent Machine.“ Advances in Computers. Vol. 6: Elsevier, 1966. 31-88. Print.

Lankshear, Colin, and Michele Knobel. New Literacies Everyday Practices and Social Learning. 3rd ed. Maidenhead: Open University Press, 2011. Print.

Latour, Bruno. “Gaia or Knowledge without Spheres.“ Aesthetics of Universal Knowledge. Eds. Schaffer, Simon, John Tresch and Pasquale Gagliardi. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2017. 169-201. Print.

Moretti, Franco. “Conjectures on World Literature.“ New Left review 1.1 (2000): 54-67. Print.

Oettermann, Stephan. The Panorama : History of a Mass Medium. New York: Zone Books, 1997. Print.

Parrish, Allison. “Language Models Can Only Write Poetry.“ Decontextualize (2021). https://posts.decontextualize.com/language-models-poetry. Accessed 8 Mar 2023.

---. “Understanding Word Vectors: A Tutorial for ‘Reading and Writing Electronic Text.’” Gist, https://gist.github.com/aparrish/2f562e3737544cf29aaf1af30362f469. Accessed 8 Mar. 2023.

Pasquinelli, Matteo, and Vladan Joler. “The Nooscope Manifested: Ai as Instrument of Knowledge Extractivism.“ AI & SOCIETY 36.4 (2021): 1263-80. Print. https://link.springer.com/10.1007/s00146-020-01097-6. 10.1007/s00146-020-01097-6.

Pold, Søren. “Panoramic Realism: An Early and Illustrative Passage from Urban Space to Media Space in Honoré De Balzac’s Parisian Novels, Ferragus and Le Père Goriot.“ Nineteenth-Century French Studies 29.1/2 (2000): 47-63. Print. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23538115.

Rettberg, Jill Walker. “Algorithmic Failure as a Humanities Methodology: Machine Learning’s Mispredictions Identify Rich Cases for Qualitative Analysis.“ Big Data & Society 9.2 (2022): 20539517221131290. Print. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/20539517221131290. 10.1177/20539517221131290.

Rettberg, Scott. Electronic Literature. Cambridge, UK ;Medford, MA, USA: Polity Press, 2018. Print.

Rieder, Bernhard. Engines of Order. Amsterdam University Press, 2020. Print. https://www.aup.nl/en/book/9789462986190/engines-of-order.

Salter, Anastasia, and Mel Stanfill. “Pivot! Thoughts on Virtual Conferencing and Elorlando 2020.“ Electronic Book Review June 6, 2021 (2021). Print. https://doi.org/10.7273/mrd4-2812.

Wing, Jeannette M. “Computational Thinking.“ Commun. ACM 49.3 (2006): 33–35. Print. https://doi.org/10.1145/1118178.1118215.

Footnotes

-

The main co-chairs were University of Bergen, Norway and Aarhus University, Denmark with partner chairs from USA and India. A full list of organizers is available at the conference website: https://conferences.au.dk/elo2021/people-and-partners.The Electronic Literature Organization (ELO) is an international organization dedicated to the investigation of literature produced for the digital medium, founded in Chicago in 1999. https://eliterature.org/ ↩

-

But also, on Discord and GatherTown and other platforms such as Easychair (for planning) and Vimeo. ↩

-

When accepting the terms and conditions of using a platform like Zoom, users allow for the collection of various data, such as basic technical information (IP address, OS details, and device details) and user account profile information (e.g., email address, first and last name). We have access to the data collected by Zoom about which and how many users connected to the sessions. For this purpose, however, we only used the transcripts of the Zoom video recordings, consented by the conference participants when they registered for the conference. The transcripts are available from the archived recordings at https://vimeo.com/showcase/8518450, and can be obtained as a collected file from the authors by request. We have not used material from Discord or other material from the conference, apart from the material, e.g., art works we reference. Furthermore, we have taken care not to reveal any personally identifiable details or comments from this data. ↩

-

The curated exhibitions were “Platforming Utopias (And Platformed Dystopias)”, “After Flash”, “Platform as a place of study: E-lit as already decolonised”, Posthuman and “Covid E-lit”). The main conference website even had a shadow art site, a “parasitic ‘flipside’” that through Recurrent Neural Network models trained on texts about the conference and Aarhus (one of the hosting cities) welcomed the virtual participants to an electronic literature version of Aarhus (AaUOS by Anders Visti and Malthe Stavning Erslev). ↩

-

See: https://support.zoom.us/hc/en-us/articles/203650745-Understanding-recording-file-formats ↩

-

Panorama comes from the Greek “πᾶν “all” + ὅραμα “view”, consequently our concepts “datarama” and “dadarama” should have been “data-orama” and “dada-orama” to fully preserve the Greek etymology, however for reasons of readability we have chosen to omit the “o”. ↩

-

To clarify what is meant by rendering: “To render, then, is to give something ‘cause to be’ or ‘hand over’ (from the Latin reddere ‘give back’) and enter into an obligation to do or make something like a decision. More familiar perhaps in computing, to render is to take an image or file and convert it into another format or apply a modification of some kind, or in the case of 3D animation or scanning. To render is to animate it or give it volume.” Andersen, Christian Ulrik and Geoff Cox, “Rendering Research ” APRJA 11, 1 (2022): 5. ↩

-

Nicolas Malevé’s use of Freire, in which he addresses the question of learning in relation to machine learning, is also useful in this respect. Malevé, Nicolas, “Machine Pedagogies,” A Peer Reviewed Newspaper 2017. ↩

-

We have taken a few literary liberties and slightly edited some of the outputs, but nothing too drastic. ↩

-

The NEXT is a platform that facilitates and promotes “the writing, publishing, and reading of literature in electronic media. It seeks to achieve this mission by making born-digital literary works and the scholarship about them accessible to the public for years to come.” [https://the-next.eliterature.org/about] ↩

Cite this article

Andersen, Christian Ulrik and Malthe Stavning Erslev, Søren Bro Pold, Pablo Velasco. "From Datarama to Dadarama: What Electronic Literature Can Teach Us on a Virtual Conference’s Rendering of Perspective." Electronic Book Review, 2 July 2023, https://doi.org/10.7273/hn47-pw06