In this conversation and accompanying "How to Not" guide, Drs. Lai-Tze Fan, Kishonna Gray, and Aynur Kadir consider responsible theories and methods towards racial equity, racial justice, and anti-racism in game design. Their main focus is on how games can provide a platform for helping people understand and learn about these issues.

Introduction

This contribution to electronic book review includes detailed Q&A with three women of colour who are scholars in games and/or race studies: Professors Lai-Tze Fan, Kishonna Gray, and Aynur Kadir. In this work, we consider responsible theories and methods towards racial equity, racial justice, and anti-racism in game design. Our main focus is on how games can provide a platform for helping people understand and learn about these issues.

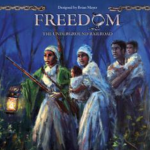

In a cultural response to the long history of racial tensions and racial injustice that continues today, critical games (or what are sometimes called "serious" games) have emerged such as Freedom, the Underground Railroad (2012) and Rise Up: The Game of People and Power (2017). Such games are developed in an effort to help players and the broader public understand sociocultural issues about race, racism, and anti-racism—each a unique topic, each deserving their own conversation.

To begin to understand the critical work of games on racial equity, in October 2020, we gathered in a roundtable to begin theorizing what racial equity game design might look like, with a foundation in board games but expanding to games in other mediated forms as well. What are the best practices? What should be avoided? Who can make games that prompt racial equity and justice, or that represent and practice anti-racism? Who can play them? The roundtable was hosted virtually through the University of Waterloo in Canada, and was co-hosted by the university's Research, Equity, Diversity and Inclusion (REDI) Council, the Games Institute (GI), and the Council for Responsible Innovation and Technology (CRIT). It anticipates a showcase to be co-hosted by these same groups, so the speakers make reference to this future showcase.

The result of the conversation is included in this contribution, touching upon the guidelines that were first outlined by the REDI, GI, and CRIT, including their objective to address issues in racial equity, racial violence, racial discrimination, and/or anti-racism in the world today through player engagement with solidly researched topics concerning the selected issue (or issues) and [through gameplay that] must make it possible for the players to learn the depth, complexity, and significance of the issue(s). Saliently, they add the stakes of racial equity in game design against recent and rising conversations in games studies that identify "serious games" as perhaps a unique or separate game genre. Their guidelines note that "serious games" communicate what we want designers to keep foremost in their minds. Racial Equity is a highly serious issue, and designers must be careful not to trivialize it, though to this mediation, we want to emphasize that racial equity is not just for those who want to take games seriously. Indeed, racial equity is everyone's problem—not just that of designers or critical players. It should, and must, be a standard in game design and play.

At the end of this publication, we have included a comprehensive "How to Not" guide of anti-racist game design practices that are to be avoided.

Transcript from the Racial Equity Board Games Panel

What are some general expectations for game submissions to a potential showcase on games that focus on anti-racism, racial equity, and racial justice?

Kishonna: Be open to critique and feedback and then make the modifications and changes. This is not a one-time thing; this is something you have to be continually invested in since there will be missteps. Folks should be open to receiving feedback and committed to doing better next time.

Lai-Tze: Games that get submitted to the showcase should include a self-aware rationale, or a rationale in general, and an awareness of the intended objectives, audiences, and potential contributions to racial equity and anti-racism.

Aynur: Gameplay creates a safe place to curate meaningful discussions so the quality of components you create and your game mechanisms must reflect the overall theme you wish to address. Accessibility with the games is very important to think about. Consider various perspectives and ask who you are designing for: kids? Avid gamers? Aim your specific strategy toward a community to better facilitate learning.

Kishonna: Make sure you're leaving space for critique and further dialogue. This is very important so that you can be ready to listen to what the community has to say.

What are expectations for what game designers must do in their process?

Kishonna: Bring everybody to the table. Make sure you're not leaving anybody out whose perspectives need to be included and ask yourself if you've incorporated them meaningfully into the design iterations and ideation phases. Have you consumed all of the content about previous examples of missteps and critiques from other board game designs? Think about what it might look like on the other end. Do an exercise of going through various perspectives and asking how different populations would receive the narratives you're designing.

Aynur: If you cannot do the work of understanding how various populations will receive your narrative, be open to asking them. If you don't have access, start with your friends or friends of friends. Discover panels like these that bring together multiple perspectives and learn from them.

Are there examples of designs where this process has been successfully implemented with a positive outcome?

Kishonna: Black Card Revoked (2015) is rooted in mainstream Black culture and knowledge and epistemologically is really recognized in the game. I brought it into a classroom and a white student talked about the fact that they felt at a disadvantage to playing the game but, after sitting with the discomfort, realized that this game doesn't have to be for them. That student used it as a learning process and enjoyed learning about black culture from the game and the people in the space with them. Black Card Revoked is an example of designing a game by us, for us, but it's also a way to educate other folks about Black culture. La Loteria is another example of this learning. La Loteria has a long history in Mexico so it has an intergenerational component. It's not about everyone being able to know everything about latinx and Hispanic culture. Rather, if you're outside the culture, these games create an opportunity for you to learn.

Lai-Tze: In addition to the student's experience with Black Card Revoked where they felt they couldn't win: sometimes the point is to lose. There isn't always a need to strategize and win when playing a game. Sometimes the point is to do critical thinking.

On the point of what we should pay attention to in terms of exemplary games: Cards Against Humanity (2011), for example, is not a politically correct game, but there are ways to hack existing games, including by creating your own cards and throwing away other cards that we don't want to perpetuate. In addition to board games, there are digital experiences and digital games. For example, the Aboriginal Territories in Cyberspace project at Concordia University, led by Jason Edward Lewis and Skawennati, funds workshops that teach Indigenous youths to create games based in their own heritages and cultures. The creative output and pedagogical structure is an example of a successful initiative towards racial equity. It doesn't always have to be about anti-racism: anti-Black racism is its own conversation and Blackness is its own conversation. These two are not the same things. One thing is a rejection of xenophobia and the other is a celebration. We should differentiate the language between racial equity and anti-racism.

Kishonna: We often have these discussions and talk about the oppression, but we also have a lot of joy. This is one of the powerful things that comes through in Black Card Revoked. Conversely, Monopoly (1935) and the Game of Life (1860) tend to leave people feeling really frustrated. A game like Black Card Revoked allows you to just be and exist in joy and happiness by seeing minute details of your culture and sharing in them collectively. Often, gamers and designers want to provide an authentic experience, but in their mind the authentic experience has to highlight the pessimism and structural inequalities. And that's not necessary. So, when you're designing these kinds of things, make a decision about your approach: if you want to be rooted in anti-racism, that's fine, but if you want to be rooted in Blackness, know that that's different.

Aynur: Many people are so afraid to be politically incorrect or are too afraid of deconstructing ideas of Indigeneity or Blackness to really understand the concurrent examples. Many times. I advise my students to read stories and autobiographies. Think about "if I had that identity, how would I respond?" There are many good examples of games [that foster this perspective-taking], like Inequality-opoly (2016) and Refugee Journeys (2018). Refugee Journeys is meant to inspire workers to help refugees and dismantle misconceptions. The game is about how you help them without showing that you are this [performative] generous entity. They come with a complex history: how does their identity factor into their coming to Canada? Players in Refugee Journeys are made to think about what these identities mean.

There's also the example of games by Indigenous designers, where players role play as a young Indigenous person moving from a reserve to a city. You have to make choices to integrate into society such as education and you have to deal with policy. What's interesting about this game is you gain resistance points to show your strengths based on your resilience. These games that bring specific personal stories, frustrations, and feelings to the table could open up genuine discussion and a good setting to understand. These can be more accessible than the complex rhetoric and discourse that deals in theory. Using a player's empathy and compassion will be good elements to include in the games.

What is your advice on portraying cultures visually without stereotyping but still educating?

Kishonna: We have learned a lot from video games and poor examples of how different races are portrayed. Avoid using these stereotypes by asking where you got this information from. If you have this impression based on other media you've seen, go and broaden your research. We need more stories to be told, so ask if your stories and narratives are adding something new. Don't just replicate what's there.

Aynur: There are tons of games that are really good bad examples. Do your homework and do your research. Try to break these stereotypes. What can you bring and enlarge the conversation in terms of your own perspective?

Is there some kind of approval scale or system for rating racial equity or queer friendliness of new games and if not, would something like that be useful? What could that entail?

Lai-Tze: There's no Bechdel test for racial equity that I know of, so maybe a "best practices guide" is something you could contribute to the showcase (or see the "How to Not" guide at the end). However, I would state that racial equity and queer friendliness should not be lumped in together. They both have their own scale since these are separate conversations.

Kishonna: There is a "Can I play that?" (CIPT) [website] hosted by Courtney Craven who does work in accessibility. CIPT answers if a game is playable to folks living with certain disabilities. I also want to caution that we should avoid reducing cultures to checklists. A scale might slip into itemizing cultures into checklists to say what is or isn't appropriate. It can be done in a meaningful way but we have to think about how we define racial equity. How are folks appearing? How are they talking to each other? This might be a cop out to doing the meaningful work because it might become about completing the checklist. It might be a meaningful guide or reference, but this cannot become easy or simple since it's not.

Lai-Tze: Initiatives for racial equity start at the beginning of design in avoiding stereotypes, but also in the labour and responsibilities. When it comes to trying to work toward better representation, what [can] end up happening is that the workload is unbalanced. Certain people are assigned to do that work since they have the authority and experience with it, but that doesn't mean that they should do all the work because that's also an unfair type of representation. And the worst part about that is it's invisible and it doesn't even show up in the final product. Who's doing the invisible labour is a big question for me. So that's something to consider: is the right representation happening the whole way?

Aynur: My suggestions to the designers are: instead of thinking from the bigger picture to your design, work from the bottom up. Is there a particular issue or story you want to address? Media plays a really powerful role in educating people. As a designer, think about what the main story is that you want to highlight. For example, I might want to tell the story of the Muslim-Chinese community that immigrated to Canada. Or I might want to talk about the wage gap in 1920. If you have the specific statistics, how can you use it to your game?

Lai-Tze: Instead of best practices, I'm thinking about the anti checklist: a list of [things that say "how to not"] and using that as the barometer.

Anti-racist work often leads to uncomfortable/painful discussions that lead to personal growth. When designing board games, how do you allow this to happen while fostering safe spaces?

Kishonna: It's important to recognize that the growth has different audiences. You'll have conversations with Black and Indigenous folks, and then conversations with white populations. These conversations will be different. You have to think about who is it that needs the growth and who's uncomfortable. It's often the more progressive liberal white folks that experience the discomfort from hearing about overt racism. Think about how growth for other folks get stunted when we have to bring white folks up to speed. The process is a journey and board games can be mobilized to do that work. Your game is not going to solve the problem, so you have to pick a specific topic you want to engage. Sometimes the space is not always going to be safe in order to have the growth. Avoid bringing everyone to the table to have the same dialogue about the topic since people will come from different points. Think about "where is my conversation happening?" Are you just jumping on the train right now? Then you have some catching up to do.

Aynur: You can have a post-game dialogue with bullet points to guide the discussion. Or, in the middle, maybe you can provide explanations. With the video game "Never Alone", any time the player has a frustrating situation, you hear from an Elder giving advice. You can foster this in your board game. Learning from each other and thinking about these issues is very important.

Lai-Tze: Having questions in the middle or at the end is a great idea. The regrouping is a good idea to support self-reflexivity. Providing resources to support a mode of conversation along with playing the game can help. Going back to the discomfort, it really depends on who is the intended audience. If this is a game on racial equity for white people, that's a very different conversation in terms of how to practice anti-racism. The resources should be designed to eliminate the possibility that racialized people have to come in and educate them. Instead, offer the resources and ask them to teach themselves. Providing the resources also helps to address the common problem that people often engage in this work and then go back to their regular lives. The better mediating process is to do the work and then think about it so you can integrate it, and it goes beyond performativity.

We're planning to do an exploratory study on social and economic factors. How would you feel about a serious game where they are used to teach specific subjects through gamified exercises and simulations?

Kishonna: We are bound by the mechanics of the space we're operating in. There are certain things you have to do, like gamifying experiences. Darfur is Dying (2006) is an example of gamifying different experiences to provoke empathy for the human experience. You have to recognize the limitations of what these tools can offer. For example, you might be just replicating playing somebody's pain. If the stories about the experience didn't provoke empathy, why will your game? Avoid exploiting pain and find a better way to articulate the experience. If you're going to do it, think about what utility its serving and be able to answer why we have to see it in order to get the point. Does it have generative value?

Lai-Tze: There are all types of problems with games that allow you to step into the shoes of someone, such as sensationalism and performativity. This type of experience-taking can become almost pornographic. [I'm referring to things like ruin porn, or] vacation photos of poor people which are a type of violence that is done upon that group and can be pornographic when considered as exploitation. It's not that it's sexual; rather, it's sensationalist and meant to provoke feeling. How can we imagine these scenarios in a respectful way without being hyperbolic and without taking up these peoples' spaces?

Aynur: Sustainability of serious games is another thing for designers to keep in mind. How can we have a longer perspective given limited resources? How can designers contribute to the longer-term maintenance and integrating feedback? How can we bring in the audiences to get better support and reception for these games?

What's in the "to avoid" list?

Lai-Tze: [Editors: See the longer guide below.]

Do not ask for people's stories. If they are out there, do not use them without their permission and consent. Do not ask BIPOC if your game is realistic enough and do not ask them to play your game in order to verify the quality of your anti-racist message unless they want to. Nobody is obligated to play your game to verify that it gets the check marks. Also, know that that's only one person's opinion and a variety is what you're looking for. Don't design games that are meant to fix the world. If your main objective is to promote anti-racist activism, then don't sidetrack that goal and don't do yourself the injustice of lumping in major themes around other topics that on their own deserve dedicated conversations. This risks watering all of it down and can be offensive to even try to tackle all those topics of inequality together – that becomes the content version of all lives matter. Finally, don't critique Black Indigenous People of Colour's (BIPOC) game design if it's not about race or racial politics. Racialized people are allowed to create and design things that just make them happy without it being about race. Racialized people are not representatives of their race and do not owe the games industry games about their identities.

What can be done on the mechanical vs. narrative level? Can you lean on the implicit message, for ex. a game that isn't immediately apparent as anti-racist?

Kishonna: It's worth asking what the utility of this is: is taking an implicit approach to being anti-racist meant to make the conversation more comfortable? I wonder why folks don't just use the words they want to and make the point they want to. These topics are urgent and yet there are privileged bodies that don't want to acknowledge the problems. I just don't have time for metaphors. If we're trying to create games to talk about certain kinds of things, we don't have time to placate peoples' feelings. There have been some amazing examples of doing this interesting work of using metaphors as stand-ins for anti-racism, but I don't have time for that.

Aynur: When we're thinking about what is fair and unfair, start off by thinking about your background. When you feel like a game is unfair, that can foster a discussion. You can get to talking about inequality when you start recognizing inequities in other games that are unrelated. But you have to have the critical thinking that helps you get there. For example, there's a game about Louis Riel's trial (High Treason: The Trial of Louis Riel [2016]), and after playing that you have to go off on your time to read about the actual history. So, when you're using implicit mechanics, there has to be a component where players go off and do more learning.

Lai-Tze: These games can be good stepping stones toward larger conversations, but those anti-racist conversations ultimately do need to happen.

How intentional do you think the ignoring of equity is in the gaming industry and how do we effectively name it?

Kishonna: I don't think there's intentional malice. For a lot of these folks, they have good intentions, but it's not part of their lexicon to talk about these things because they come from very privileged perspectives. We have to always insert ourselves into these conversations because we're an afterthought, and then people always resist with other excuses. People want things to stay the way they are. The chore is to get them to move outside of that and break the "othering". I'm more generous than I ought to be by showing them their errors, but if they continue to do it then that's where actual fault comes in.

Lai-Tze: A common game industry excuse is to say that you can't change something once the game comes out, but that's not necessarily true. You can fix a bug? Then you can fix something racist. You can correct a design flaw. Pokémon GO (2016) is an example of this fail. There's an article called Pokéwalking While Black: Pokémon GO and America's 'e-quality' of life that talks about the systemic racism and lack of access based on race. The intended access didn't end up being what they designed, but they realized that they should have fixed it instead of letting it go on.

What's at stake if we don't start taking innovative approaches to innovation?

Kishonna: What's at stake really impacts the people who are marginalized, but for the privileged there's nothing at stake for you. I would just hope we can activate more allies in the conversation. People who are in positions of power should want to do this work because they recognize marginalized folks have limited access for doing this work. I wish more people would recognize the power they have through their platforms and tools at their disposal. What's at stake is the continued ethnic cleansing, genocide, and death of people that matter to us. If that matters to you all but you say, "I can't do much but I can make a game," then make that game about educating others. For example, educate players about the difference between defund the police and reform the police so that folks can understand there is no reforming.

Aynur: Racism is a structural phenomenon. Many folks say they are not racist or "do we have racism?" But there is racism in every society. The beginning is about acknowledging there is a problem and then, as a community, you come together to change it to have a better future. We like to think we've come a long way but still, people make basic mistakes. Despite the fact that race doesn't have a real biological definition, racism is real. Use this education to create that inclusive society for humanity's sake. That's what we're fighting for.

Lai-Tze: This is a very 101 question, asking us to return to the beginning. It's not really worth discussing since it's so obvious. But what we can look at is the innovative education pieces. We can use innovative education to reach folks that otherwise don't have that access. At the very least, we can connect people to more resources through knowledge mobilization. Also, the purpose is not for all of us to preach to the converted, so we can use education to reach the folks that don't agree with us yet. That's the difficult work.

Are there any final thoughts to share?

Kishonna: I want people to go away not feeling defeated. If you're experiencing discomfort, I want you to think about why. If you feel unequipped or not up to the task, this is where your growth will happen. I want this to encourage you to do that growth and do the best work you can. Don't be afraid of messing up; be open to learning and doing better. If you do that, you'll have comfort in knowing that the work you put out will be a result of your growth.

Aynur: My advice to designers is to collaborate. You can invite BIPOC folks to be co-designers. Give them power to make decisions by taking away your own complete control and power. When it's out of your control, it will be uncomfortable, but challenge that. If there are four people in the team, and all of you are designers, can you make a game that works? And for BIPOC folks, you don't have to give up your stories, but you can work with folks to help get your story out there. Come up with a collaborative strategy to do this challenge.

Lai-Tze: I'm glad that this conversation was able to happen. It needs to happen and can hopefully foster a showcase that will facilitate more conversations. If you're tired from listening, I promise you we're tired from talking. I wanted this conversation to happen, but I want folks who want to participate in the showcase to really think about if you can do it. If you really think you have something to add, then do it. We're rooting for you.

How to Not: A Guide to Avoiding Worst Practices

This Guide serves as a response to the use of best practices in racial equity in game design. The intention is to avoid the use of didactic checklists that, upon completion, may grant permission to designers to feel as if their ethical and equitable work has been accomplished and does not require further contemplation or consultation.

In response, we have created a How to Not Guide in order to identify what practices in racial equity design should be avoided. While this Guide was written by Lai-Tze Fan, its contents, objectives, and ethos was approved by all three authors.

- Don't ask for stories. If personal stories are offered to you, double and triple check that someone consents to their reproduction in your game. If stories are shared publicly, check anyway: don't use others' stories without permission and check whether or not those who offer personal stories want to be named and credited. Along this line, Twitter user @razorfemme argued on October 18, 2020, that "Sometimes when people ask you to tell your story, what they are really saying is: Bleed for me."

- Don't ask BIPOC if your game is "realistic" enough. People don't owe you their stories nor insights for standards of racial equity or racial trauma.

- Don't ask BIPOC to play and verify the quality of your anti-racist message unless they want to.

- Don't design any character role-play that relies on the painful and harmful performance of racialized identities, especially where appropriation, mockery, or satire is involved.

- Don't design games that are meant to fix all problems of racism. If your game's main objective is to promote anti-racist activism, don't sidetrack that goal by bringing in major themes around, for instance, women's rights and child labour. Each of those topics deserve their own conversations and to lump them together waters all of them down. It's offensive—in fact, it's the content version of All Lives Matter.

- Don't critique BIPOC's game design if the content does not involve racial politics. They are allowed to create and design things that make them happy. They are not representatives of their entire race and do not owe game industries their racial politics just because they're racialized.