Like many of the "Artistic Reflections" featured in the Cork 2019 e-lit conference, Carpenter's opens out from her own web based works to a "post-digital world, in which invisible layers of data inform our daily thoughts and actions; a post-human world, of vast oceans and ceaseless winds."

This essay considers literary realism in relation to two of my own recent works of digital literature: This is a Picture of Wind: A Weather Poem for Phones, and The Pleasure of the Coast: A Hydro-graphic Novel. Both of these web-based works grapple with the actual world we live in: a post-digital world, in which invisible layers of data inform our daily thoughts and actions; a post-human world, of vast oceans and ceaseless winds. These works use the affordances of the internet to call attention to the historical, colonial, elemental, and material substrate of the internet; both attempt to represent the reality of the vast corpus of non-human writing which lurks beneath the mere appearance of the screen. Methodologically, this essay grapples with the material and contextual actualities of these works by turning its attention to earlier analogous moments in the intertwined histories of technology, science, and writing. In particular, this essay is concerned with the technology of the ship, the science of measurement, and the writing of the vast non-human systems of coastlines and winds.

In “Mapping’s Intelligent Agents,” Shannon Mattern stresses that “we need to keep asking critical questions about how machines conceptualize and operationalize space. How do they render our world measurable, navigable, usable, conservable?” (n.p.). I agree that we need to ask these questions forward, of writing machines, of machines of surveillance, of the GPS tracking devices we carry in our pockets, and of the Google Street view cameras paving the way for a world navigable by self-driving cars. But we also need to keep asking these questions backwards, applying this critical frame to earlier navigational regimes.

For most of human history the ship was the fastest we could travel, the furthest we could think. It’s no mere coincidence that the logo for Netscape Navigator, the world’s first widely publicly accessible web browser, combined a distant horizon and a ship’s wheel. The ship’s passage is defined by a rudder, a vertical blade at the stern of the ship that can be turned horizontally to change the ship’s direction when it is in motion. The word ‘rudder’ is akin to the word ‘row’, the ship’s rudder being a descendant of the humble oar. The word ‘rudder’ also bears a close association with the word ‘router’ or ‘route’ from the Old French meaning road, way, or path, from the Latin rupta, meaning a road opened by force. A ship’s rudder is a thing which routes; it opens a road in the sea. During the years 1873-76 the British ship H.M.S. Challenger sailed the globe taking soundings of the ocean floor. This research was necessary to the establishment of a global submarine telegraph network (Murray & Thomson 1885). Most of the world’s digital data now flows through submarine fiber optic cables laid along roughly these same routes.

The Pleasure of the Coast: A Hydrographic Novel is a web-based work commissioned by the ‘Worlds, interfaces and environments in the digital age’ research group at Université Paris 8, in partnership with the cartographic collections at the Archives Nationales in Paris. This work asks questions about how the ship made the world measurable and thus navigable for western imperialism. It does this through the reactivation and reorganization of a 225-year-old data set held at the Archives nationales: a collection of sketches showing coastal elevations along with drafts of sea charts drawn by Charles-François Beautemps-Beaupré (1766-1854) during a voyage for discovery to the South Pacific in the late eighteenth century.

In 1785 Louis XVI appointed Jean-François de Galaup, comte de Lapérouse to lead an expedition around the world. The aim of this voyage was to complete the discoveries made by the English Captain James Cook on his three earlier voyages to the Pacific. On the 1st of August 1785, Lapérouse departed Brest with ten scientists aboard. On the 10th of March 1788, Lapérouse departed the English colony at new South Wales, Australia. He was never seen by European eyes again. On 25 September 1791, Rear Admiral Bruni d’Entrecasteaux departed from Brest in search of the lost Lapérouse. To the English ear, the name Lapérouse sounds a lot like the verb ‘to peruse’ — to scan or browse, to read through with thoroughness, to survey or examine in detail. The dictionary cautions, the word ‘peruse’ can be confused with the verb ‘to pursue’ — to follow in order to overtake, to strive to gain, to seek to attain, to proceed in accordance with a method, to carry on or continue. The English word ‘pursue’ sounds a bit like the French word ‘perdu’ — disposable, ruined, lost.

Beautemps-Beaupré sailed on one of d’Entrecasteaux’s two 500-ton frigates. The ship was called La Recherche (The Research). Beautemps-Beaupré was twenty-five years old at the time. He went on to become the founding father of French Hydrography. Hydrography is to the sea what cartography is to the land. Sybil Krämer has observed that during the so-called ‘Age of Discovery’ cartography underwent a profound reformation: “map producers abandoned the elaborate and fantastic projections created in their studios and exchanged them for fieldwork in a landscape whose topology was exactly quantifiable” (188). Through the operations of measurement and direct observation, map-making was transformed from an art to a science.

In his Introduction to The Practice of Nautical Surveying, Beautemps-Beaupré wrote that by the time of his first voyage to the South Pacific in 1791:

“Every sea had been explored, and there remained no great discoveries to be made. The latitudes and longitudes of a great number of important positions had been determined, and these positions had become the bases on which the corrections of marine charts were to be founded” (1).

Science is an accumulation of systematic knowledge about the real world. Through the standardization of cartographic and hydrographic techniques during this period, a quantifiable ‘New World’ was written over the surface of a topography which had already been inscribed by its inhabitants through thousands of years of use. The map became a metaphor, a symbolic representation of a terrain that it strove to approximate exactly.

The Pleasure of the Coast aims to disrupt this assumptive relation between the symbolic and the real. Exactitude is eschewed. The work is imperfectly bilingual. The user navigates long, horizontally-scrolling cartographic collages composed of sketches of coastal elevations made by Beautemps-Beaupré aboard La Recherche. These documents show the active marks of a practicing hand, liquid lines of inquiry drawn in oak gall ink on a wind-born ship floating on a fluid sea.

The title and much of the text in this work détournes Roland Barthes’ The Pleasure of the Text, first published in French in 1973. Barthes’ proposed opposition between readerly and writerly texts prefigures the notion of a post-digital literary realism put forward by this essay. In Roland Barthes by Roland Barthes he writes, a readerly text “is one I cannot rewrite (can I write today like Balzac?); a writerly text is one I read with difficulty, unless I completely transform my reading regime” (118).

For Barthes, the difficult, writerly text is bliss. For me, coastlines constitute non-human lines of writing. In my PhD thesis, Writing Coastlines, I argued that coastlines are edges, ledges, legible lines caught in the double bind of writing and erasing: “The act of writing translates physical, aural, mental, and/or digital processes into marks, actions, utterances and/or speech-acts. Wave action translates a physical process into a set of marks… The action of a wave is legible in the sand that it has just washed over. But sands shift, winds lift, cliffs crumble (68). Coastlines are texts which are read with difficulty. They require a transformational reading regime. Beautemp-Beaupré’s manual for nautical surveying is full of anxiety about how best to read and write the coast:

having ascertained the possibility of measuring a great number of angles at the same instant, I conjectured that the most correct and easy method of laying down the points or positions corresponding with these angles, taken from a station either afloat or on shore, was still to be sought for: the system of using the letters of the alphabet and arithmetical figures, to denote objects which were not yet named […] exposed [the observer] to the commission of errors so much […] there was not a hope of proving their existence or extent (2).

Barthes concedes: “there may be a third textual entity: […] the unreaderly text […] the red-hot text […] whose function […] would be to contest the mercantile constraint of what is written; this text […] armed by a notion of the unpublishable, would require the following response: I can neither read nor write what you produce, but I receive it, like a fire, a drug, an enigmatic disorganization” (118).

In The Pleasure of the Coast, passages of Bathes’ détourned philosophy intermingle with technical writing by Beautemps-Beaupré. These unattributed and often indistinguishable voices are in turn interrupted by excerpts from a third textual entity. In Suzanne and the Pacific, a symbolist novel by Jean Giraudoux, first published in French in 1921, a young French woman becomes shipwrecked on an island in the region of the Pacific charted by Beautemps-Beaupré. In the following passage The Pleasure of the Coast this tripartite language system of symbolism, science, and philosophy unfurls and folds in on itself:

I left for another world as if for a coasting voyage, innocently; trying to see all of France, like an island, as I left it behind. I made a sketch of the land commencing with those parts which, being most remote, were the least liable to change in appearance. I savored the sway of formulas, the reversal of origins, the ease which brings the anterior coast out of the subsequent coast. At last the sky appeared, the whole sky, so pure, so laden with stars.

In his introduction to a 1964 edition of Suzanne et le Pacific, Roy Lewis states: “The realist writer assumes… that there is an objective world which it is [their] duty to describe accurately and unambiguously” (20). It’s for this very reason that, writing in the 1970s Barthes stated: “Realism is always timid… there is too much surprise in a world which mass media [has] made so profuse that it is no longer possible to figure it projectively: the world, as a literary object, escapes; knowledge deserts literature…” (119). In Gramophone, Film, Typewriter, first published in 1986, Friedrich Kittler suggested that writing stored in books is always self-conscious and subjective, laden with meaning, and thus limited. Mechanisation, Kittler argued, “permits a linguistic hodgepodge hitherto stifled by the monopoly of writing… The epoch of nonsense, our epoch, can begin” (86). In our post-digital epoch, the vast majority of the text produced by computer systems is nonsensical to most humans. As our use of digital devices grows, text we did not write and cannot read underwrites the language of ordinary rational discourse. In her essay “Realism for the Cause of Future Revolution,” first published in 1984, Kathy Acker proclaimed: “The only reaction against an unbearable society is equally unbearable nonsense” (18).

The Pleasure of the Coast does not assume an objective world. Rather, it tries to reveal some of the messy sketchy subjectivities lurking beneath the surface of the science of imperial measurement. Epeli Hau’ofa observes that Europeans, on entering the Pacific after crossing huge expanses of ocean, tended to see ‘islands in a far sea’ rather than ‘a sea of islands’: “Europeans and Americans drew imaginary lines across the sea, making the colonial boundaries that confined ocean peoples to tiny spaces for the first time. These boundaries today define the island states and territories of the Pacific” (152-153). The Pleasure of the Coast blurs colonial boundaries by calling attention to the moment that they were drawn. It disorganizes the sea of island carefully recorded by Beautemps-Beaupré, turning them into a variable font for use in the writing of willfully impossible word archipelagoes. Through the détournement of Barthes, the hydrographer becomes a libidinal, desiring body, taking pleasure in a rewriting coast which is also actively writing according to its own agency.

Wind was the invisible force powering colonial expansion. Beautemps-Beaupré lived and worked in a world driven by wind. He was a close contemporary of the Irish-born British Admiralty Hydrographer Francis Beaufort (1774-1857). Posthumously Beaufort is most commonly associated with the scale named after him, for measuring the force of the wind. As Scott Huler observes, “Francis Beaufort didn’t actually write the Beaufort Scale” (72). Rather, he put it in to action. Data collected by wind-powered sailing ships during this period continues to inform our daily thoughts and actions. Consider the weather app on your mobile phone, for example. Historical weather data recorded in Admiralty ships’ logs under the direction of Beaufort contributes to the accuracy of long-range weather forecasting.

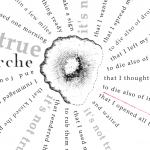

The Beaufort Scale informs the poetic structure of another recent work of digital literature. This is a Picture of Wind: A Weather Poem for Phones was commissioned by the IOTA Institute in Canada. A sea chart of the waters off the coast of South West of England underlies a calendrical rather than longitudinal grid. Numbers denoting ocean depths intermingle with the words of a part fixed, part variable poem composed of three type of textual data: fragments culled from a vast corpus of English science and nature writing, prose poems composed through sustained quotidian observation of a specific landscape, and couplets randomly generated in part by live wind data and in part by the inexorable passage of time.

Johanna Drucker has observed that the language in This is a Picture of Wind is not metaphorical, but rather, it

grapples with the actual, addressing the difficulty of bringing sensing and knowing together. […] The grid arbitrarily marks our days and months off from each other. […] The wind rushes through the rational structure, even as it leaves behind […] a residue of poetic notes, observations formulated in relation to fleeting sensations of the volatile atmosphere (22).

At the time of this writing the digital iteration of this work contains two years of wind. One year is based on quotidian observations of the River Dart at Sharpham in Devon 2009-2016. The other is based on barometric observations recorded by the British meteorologist Luke Howard at Tottenham in the early 1800s. A print book iteration of this work forthcoming from Longbarrow Press in June 2020 will introduce a third year, based on Vita Sackville-West’s writing about her garden at Sissinghurst in the early twentieth-century. This third year will be added to the digital work over the course of 2020. In this way, the digital work remains an open-ended structure able to change in response to the ongoing forces of wind, air pressure, and plants in flower.

Digital imaging techniques allow us to bring historical strata of hydrographic data out of the archives onto the screen. Application Programming Interfaces (APIs) allow us to interact directly with live weather data. At the same time, rising sea levels “imperil the delicate web of cables and power stations that control the internet” (Borunda n.p.). Realistically, as authors and critics of digital literature, we have to ask ourselves, what is the good of recording all this data if we are also in the process of erasing it through climate change? Both of the recent works of digital literature discussed in this essay seek language for vast non-human narratives unfolding beyond the time scale of the human body; invisible territories of data expand beyond the peripheries of human comprehension. Kathy Acker implores: “Let one of art criticism's languages be silence so that we can hear the sounds of the body: the winds and voices from far-off shores, the sounds of the unknown” (92). And so these works seek to address the limits of our comprehension, to call attention to the vulnerability of our libidinal desiring bodies, to depict the actual in human terms that we can understand and act upon.

Works Cited

Acker, Kathy. Bodies of Work. London: Serpent’s Tail, 1997. Book.

Barthes, Roland. The Pleasure of the Text. Richard Miller, trans. Berkeley & Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1975. Book.

Barthes, Roland. Roland Barthes by Roland Barthes. Richard Miller, trans. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1977. Book.

Beautemps-Beaupré, Charles François. An Introduction the Practice of Nautical Surveying, and the Construction of Sea-Charts. Richard Copeland, trans. London: R. H. Laurie, 1823. Book.

Borunda, Alejandra. “The Internet Is Drowning,” National Geographic. Wednesday, 18 July 2018. Online Article. https://www.nationalgeographic.co.uk/science-and-technology/2018/07/internet-drowning

Carpenter, J. R. The Pleasure of the Coast: A Hydro-graphic Novel. 2019. Web. http://luckysoap.com/pleasurecoast

Carpenter, J. R. **This is a Picture of Wind. **2018. Web. http://luckysoap.com/apictureofwind

Carpenter, J. R. Writing Coastlines: Locating Narrative Resonance in Transatlantic Communications Networks. London: University of the Arts London, 2015. PhD thesis. http://ualresearchonline.arts.ac.uk/7825/

Drucker, Johanna. “Dynamic Poetics: J. R. Carpenter’s This is a Picture of Wind,” IOTA:DATA Carpenter / Chan / Solo. Halifax: Iota Institute, 2019. E-Pub. https://www.iotainstitute.com/s/IOTA-DATA_CarpenterChanSolo.pdf

Giraudoux, Jean. Suzanne et le Pacifique. Roy Lewis, ed. London: University of London Press, 1964. Book.

Hau’ofa, Epeli. “Our Sea of Islands,” _The Contemporary Pacific, Volume 6, Number1, Spring 1994, 147–161.

Huler, Scott. Defining the Wind: The Beaufort Scale, and how a 19th-century Admiral Turned Science in to Poetry. NY: Crown Publishers, 2004. Book.

Krämer, Sybille. Medium, Messenger, Transmission: An Approach to Media Philosophy. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2015. Book.

Kittler, Friedrich. Gramophone, Film, Typewriter. translated from German, with and introduction by G. Winthrop-Young and M. Wutz, Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 1999. Book.

Mattern, Shannon. “Mapping’s Intelligent Agents,” Places Journal, 2017. Web. https://placesjournal.org/article/mappings-intelligent-agents/

Murray, J. & Thomson, C. W. Report on the Scientific Results of the Voyage of H.M.S. Challenger During the Years 1873-76. London: By Order of Her Majesty’s Government, 1885. Book.

Skirgård, Hedvig. “A Sea of Islands - Oceania as grouped by overnight voyages in traditional Polynesian canoes,” https://sites.google.com/site/hedvigskirgard/pacific-maps/pacific-maps-old#h.p_2hm2_kI60dWE