New = Old, Old = New

Jan Baetens argues that Chris Ware's print-based comic book, Jimmy Corrigan, has already produced the revolution longed for by Scott McCloud - a revolution, however, that will not be digitized.

There was already something weird, and maybe something wrong, with the first book by Scott McCloud on comics art, the widely acclaimed Understanding Comics (HarperCollins, 1994). thREAD to the Sabin discussion of Understanding Comics And today, something is still more weird and wrong with its sequel, Reinventing Comics: How Imagination and Technology Are Revolutionizing an Art Form. For many readers, the analysis of the medium proposed by the first book has always seemed a little simplistic, and not really up-to-date. McCloud’s work had already been accomplished by several other theoreticians, for example by Thierry Groensteen in Bande Dessinée: Récit et Modernité (Paris: Futuropolis, 1987) and Benoit Peeters in Case, Planche, Récit (Paris/Tournai: Casterman, 1991). Although McCloud put his message in a pleasant ars poetica form based upon a certain coincidence of showing and telling - the essay on comics is a comic book itself - there was not much to learn about the language of comics in Understanding Comics.

Reinventing Comics displays still more overtly than its predecessor why McCloud’s approach is so impoverishing and disappointing. Before focusing - with strong reservations - on the way the author examines the digital revolution in comics, I would like to recapitulate why this book, a rather unimaginative continuance of Understanding Comics, does not represent for me the ideal introduction to the field so many (mostly non-comics) readers see in it.

Theoretically speaking, McCloud is a follower of Will Eisner, whose Comics and Sequential Art (Poorhouse Press, 1985) provides him with a strong but narrowly-defined model. Eisner, who coined the concept of “graphic novel” to stress the literary ambition of the “art” comics, wants comics to tell stories. This fundamental scope of more or less linear storytelling controls and directs the use of the medium’s formal devices as a sequence of panels - an assumption not false in itself, but one that implies a radical dichotomy of telling and showing, the first determining the latter. Comics embody narratives, they are visual meat put on the conceptual bones of a story. For Eisner and McCloud, comics images have a fundamentally illustrative role to play, and this a priori makes Understanding Comics and Reinventing Comics so boring. For instead of showing visually what he wants to explain, McCloud repeats with an icon in each panel what is said in the captions and balloons. While this didactic device may be funny and amusing on some pages, or even throughout whole chapters, the technique ultimately reveals itself as useless, if not counter-productive. Why go on drawing indeed if everything is told and explained verbally anyway? Many efforts have been made to introduce to comics a “meta-representative” or self-reflexive mode or dimension (see Conséquences 1991:13/14, entirely dedicated to this matter), where the reading of the image as well as the text helps the reader to discover the possibilities and strategies of comic storytelling and comics language - the two are not at all the same, as Eisner and McCloud seem implicitly to believe.

The case becomes all the more problematic because McCloud shrinks his corpus even more ruthlessly in Reinventing Comics. His thesis that comics are basically sequences of panels covers only a small part of the formal devices of the medium. McCloud goes much farther in Reinventing Comics with his “own” cultural tradition, that of American comics. Indeed, despite all his good intentions to open up the medium and break the domination of mainstream comics, McCloud falls prey to his excessively narrow conception of the panel as the basic unit of storytelling. Some sections of Reinventing Comics present a survey of the history of comics, including a great variety of visual quotations of non-mainstream examples. On the one hand, one can only be delighted by such an anthology (and by the good taste of McCloud, who knows his “modern classics” very well). But on the other hand, one should feel horrified by the way the author systematically erases the formal characteristics of the quoted sources. Only small fragments - generally just a panel, and often only small panel fragments - are taken from the original artwork, and these fragments always appear in McCloud’s specific and very stereotypical page layout. The selection of small portions can be understood, and largely excused, for reasons of copyright. The insertion of these portions into McCloud’s page layout is more difficult to forgive, since it produces an overall misrepresentation of the sources. McCloud’s integration of the pieces of his anthology resembles, mutatis mundis, those prose pieces that quote traditional (i.e. versified and patterned) poetry without making the slightest effort to stress the fact that the quoted words are not prose but poetry.

Understanding Comics supplied the demand of the larger audience looking for an easy companion to comics unavailable at that time on the (American) market. From an historical viewpoint, the book has done a good job; despite reservations about the theoretical and practical underpinnings of McCloud’s approach, it would be silly to deny that. The case of Reinventing Comics is much more ambivalent, since the book wants to simultaneously give an answer to the crisis of the comics market, endemic for more than a decade, and sketch a way out to a brighter future. The plea for the medium becomes, for the comic artist Scott McCloud, a professional plea pro bono. A small independent artist and entrepreneur, McCloud suffers from the effects of collapsing retail sales, and his renewed reflection on the comics business bears many undertones of small enterprise.

McCloud’s main line of defense in Reinventing Comics is two-fold. First, he tries to convince us that comics has been a poor genre for the last hundred years, and that it now has to go through a set of “revolutions” in order to become “art.” Many, if not all of the so-called revolutions, however, are long since behind us, at least in Europe. Only the straw man’s argument of explicit reduction of the comics field to mainstream superhero stuff can explain why McCloud wants to consider his thesis as revolutionary. Moreover, his arguments sound rather hollow as his own graphic style is hardly innovative. If the new comics authors of tomorrow draw like McCloud, then one may reasonably prefer their outdated or forgotten counterparts. In fact, the truly fundamental issues concerning the renewal or revolution of comics language are never raised by McCloud. Indeed, if the readership tends to reject comics - or at least the “art” comics which help McCloud make his living - the problem has much more to do with society than with the structure of the medium or with the qualities or insufficiencies of its language. What’s the use of “reinventing” comics if the much more daring and challenging work of the great masters has never met with any success? Why not try first of all to promote the work of those masters? Why not analyze the reasons for their commercial failure? Why not investigate why creating and maintaining a comics heritage is so difficult?

Second, McCloud states that the real revolution to come will be - and in part already is - a digital one. Thanks to the Internet, comics can become infinite, for the screen, as McCloud puts it, is not a “page” but a “window,” and it gives access to a whole new universe where the sky of our imagination will be the only limit, where rights of the creators will be at last recognized and respected, where the reading process will cease to be passive and become truly interactive, etc. I intentionally add “etc.” because this array of commonplaces is nowadays well-known as what it actually is: an array of commonplaces. The examples of digital comics given are not exciting at all: with a bad wordplay, one could say that “Digital Comics” à la McCloud are no more interesting the “DC”-comics he rightly despises. Further, and more problematically, McCloud’s digital comics fail to formulate some crucial interrogations; for instance, ownership of the media. If the Internet will help some small entrepreneurs such as Scott McCloud gain independence from the great big wolf of the comics industry - always an easy target, but let’s not forget such genial authors as Herriman, who worked for the industry all his life - why not imagine that it will also give birth to net-piracy on a planetary scale, and so bring to an end the very short history of individual copyright and textual ownership? Another issue on which McCloud remains curiously silent is the matter of artistic identity, both that of the “medium” and that of the “author.” The idea of a migration from print-based to digital comics is terribly naive, since what we are facing is not a permanent supersession of one medium by another, but a no less permanent mutual complexification and reciprocal feedback. Every new medium redefines the existing mediasphere, and in turn is challenged, influenced, and transformed by that mediasphere. Technological revolutions are neither linear nor unproblematic: each revolution or change is the theatre of a new repositioning of all actors in the field, just as the print-based comics are not condemned to mere obsolescence, but forced to better explore their own specific constraints and opportunities - and there are no opportunities without constraints! Writing Under Constraint - digital comics will never become a new island or continent, they will never achieve the splendid isolation McCloud is longing for, far away from the stupid crowd of superhero booklets. The future of comics, then, will not reside in the inventing or reinventing of some “type” (in this case digital) of comics, but in the inventing and reinforcing of new relationships between the types available in a certain time and space. That in such a context there will no longer be room for “individuals,” but only for networks of dialoguing and collaborating users-consumers-creators-researchers, is a logical step of technological evolution Reinventing Comics is of course not willing - or ideologically able - to take. Imagine a scientific lab where one person would do all the thinking by him- or herself. That’s how McCloud imagines his own digital Nirvana (see the front cover of the book, where the author is represented as a smiling Buddha-like figure).

Let us leave him there and come back down to earth with Chris Ware’s Jimmy Corrigan, The Smartest Kid on Earth, a book, just a comics book, but a comics book unlike any other. Music to Slit Your Wrists By

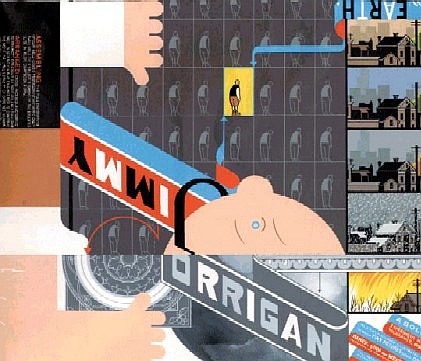

The first thing to notice about Jimmy Corrigan is that it is a heavy, old-fashioned, hard to handle, often difficult to read, book, but it nonetheless does exactly what McCloud wants his digital fiction to do in the near future. Already the dust jacket of the book, once folded out and read on both sides, is a masterful exploration of what reading ought to be: the discovery of a world in a nutshell. Chris Ware does not need the ultimate unboundedness and infinite space of the Internet to establish a whole universe of stories, places, and characters: in comparison with this double-sided printed sheet, the clicking and linking dreams of McCloud seem futile and pointless.

Jimmy Corrigan is not the mere illustration of the revolutionary comic as art (sorry, as Art) that McCloud calls for. It is also, for two reasons, the exact opposite of it. First, Ware’s work follows a logic which is mainly visual rather than verbo-narrative, and second, it does not strictly obey the claim of infiniteness. For those two reasons, Jimmy Corrigan is able to produce the revolution that digital comics have failed to produce until now. Ware uses constraints; that is, he reduces the number of units, aspects, colors, forms, etc., to create the possibility of a more complex, multi-layered, poly-sequential writing and reading in which the reader has no right to play freely with the author’s arrangement of material, but must scrupulously follow it to slowly discover the myriad relationships on the page itself. Although the dust jacket of the book is not McCloud’s “window” on the world but a sheet of paper whose opacity is almost entire, it nevertheless manages to confront the reader with a complete universe.

CAPTIONMARKERSTARTThe dust jacket of Jimmy CorriganCAPTIONMARKEREND

CAPTIONMARKERSTARTThe dust jacket of Jimmy CorriganCAPTIONMARKEREND

Moreover, the reading path is indicated by arrows which at first sight seem to reduce the freedom of the user, but which very soon reveal themselves as the necessary condition of a serious construction of the page and of the images. Thanks to the organization of the plate and its sequential orderings, for several reading paths are suggested, it becomes possible to both construct and deconstruct the traditional way of reading without engendering a chaos whose apparent creative advantages are always rapidly lost.

The unusual minimalism of the drawing style and the story are also indispensable allies of this hyper-constructed “less is more” aesthetics. Objects and characters are executed in a style reminiscent of the international visual language as developed by, for instance, Otto Neurath in 1936. Neurath’s approximately 2000 “isotypes” and accompanying pictorial grammar can be considered one of the first occurrences of the various contemporary pictogram sets. Such an eminently “impersonal” style, using again and again the same “minimal forms,” helps to visually gather certain elements which “in reality” have no direct relationships; for example, circle-like or triangle-like shapes shared by, say, the head of a character and the cheeseburger he is eating. In Jimmy Corrigan, the page is generally divided into small panels displaying immobile scenes and showing only very minute changes from one image to another. This lack of movement blocks the sequentiality of the reading, and why go on stressing the importance of sequential reading, whatever the chosen reading path may be, if “nothing happens”? At the same time, the lack of movement strongly emphasizes a reading mode which both underlines the global reading of groups of panels and manages to do away with the panel as the central unit of narration and reading. What happens in Ware’s fiction is a phenomenon of semiotic “articulation”; i.e., of dividing a unit into its smaller, meaningful components on the one hand, and of integrating this unit into an element of a superior level on the other. Articulation is often considered more characteristic of verbal language than of images. Indeed, one of the most popular stereotypes of the semiotic interpretation of an image is that it is not possible to “cut up” an image, that one has to consider it always as a “whole.” But here Ware applies articulation in an eminently visual way; forms and colors are used as the letters of an alphabet, and their combinations are almost infinite.

This perspective of infinite combination appears very clearly in the narrativity of a work whose panels and page layouts seem, at least at first sight, to be absolutely static. In Jimmy Corrigan, the temporal art of storytelling is no longer based upon the successive reading of panels, each detailing a segment of an action or a movement, but created with techniques that, crucially, converge towards an astonishing dynamization of the plates.

First, given the reduced sizes of many images - and even more of the texts, which are sometimes hardly readable - it is no longer possible to distinguish the panel as an autonomous structure. So strong is the presence of the surrounding panels that one is unavoidably forced to grasp several images at the same time. The very distinction of screen and off-screen no longer holds; panels stick together despite the absolute immobility of what they represent. This abolition of the panel’s autonomy is a perfect illustration of the continuity between Jimmy Corrigan and the greatest examples of comic history: Winsor McCay’s Little Nemo in Slumberland and George Herriman’s Krazy Kat. However, Ware does not limit himself to a mere - and in his case a very hard-edged - reactualization of their multi-layered and resolutely delinearized plates, he also reinterpets the relationship of character and setting. All three authors pay equal attention to the balance between the equivalently-valued narrative parameters of character and setting (settings perform as characters in McCay and Herriman’s work as well as in that of Ware). The distinction is that while Little Nemo in Slumberland and Krazy Kat are still able to acknowledge the magic of the places they exhibit and transform, Jimmy Corrigan is a comic strip in which the setting bears the traces of history. Just as the characters shift from youth to old age and undergo many cross-generational changes, the places of the book achieve an historical depth which is very different from the fictitious and luxuriant settings invented by McCay and Herriman. In Ware’s work, people really die, and they do not simply die, but they get old and sick and then die after a long and painful process of physical and mental deterioration; the places also die, nature is destroyed and settings collapse - the very life of things is similar to that of the human beings inhabiting them. In the comics field, such an historic consciousness is exceptional, and it introduces in Jimmy Corrigan an almost epic, but totally unheroic dimension which was lacking in the dehistoricized fantasy worlds of the Little Nemo and Krazy Kat characters.

A second feature I would like to underline here is the very astute multiplication of narrative threads throughout the whole work. Instead of going “simply” backwards and forwards in the life stories of the Corrigan family, Ware uses a narrative technique of linking and unlinking which represents for me the first real illustration, or transposition if you will, of the technique of “narrative generators.” This technique was explored in the sixties and the seventies by New Novelists such as Jean Ricardou (Le Nouveau Roman, Paris: Seuil, 1973) and Raymond Federman (Surfiction: Fiction Now… and Tomorrow, Chicago: Swallow Press, 1975). Fed Ex Un Ltd A “generator” might be a key word whose occurrence in the verbal stream of the work creates, not a reinforcement of its thematic tissue, but an opportunity for a narrative shift, an occasion for breaking the narrative line in order to give the story a new direction. A simple but good example of a generator is of course the homonyms of puns, whose twofold meanings allow the storyteller to bifurcate or to pick up a thread which had broken before. The ubiquity of word-play and verbal confusion in Jimmy Corrigan - where communication is often difficult due to external noise, deafness, or distraction - creates a story whose line can be broken at any moment, and whose meandering digressions can also be apparently re-ordered at any moment. This technique also explains why the graphic immobility of Ware’s style is not an obstacle to the disturbing yet samba-like surprises of an unendingly unfolding storyline.

A third mechanism of such a paradoxical narrativization is the presence, reuse, and remediation of other types of images, in this case of other types of narrative images: war pictures, tourist post cards, several examples of 19th century viewing machines studied by Jonathan Crary in Techniques of the Observer (MIT 1991), other comic strips, cinema, and Muybridge’s experiments with a certain mode of chronophotography. The active dialogue with all these sorts of images, which often plays a role in one of the storylines, produces in the Jimmy Corrigan plates a duplicity and a memory which radically makes every image tell in itself, as a form, a thousand stories. But once again Ware does much more than just remind the reader that each image is the result of a historical process, he also shows to what extent each new image is in struggle with its own past, and with the whole past of visual storytelling. Muybridge’s horses, which are inextricably linked with many thematic elements of the book, act both as generating and generated key items (we cannot know what came first: the Muybridge images, or the remembrance of the grandfather’s carriage), and the way they are remade by Ware exemplifies the critical distance the author takes to his models. Muybridge’s horses are not used in order to create an always unfaithful recomposition of a linear movement, but as an illustration of the impossible longing for it; they are there to show that such a naive vision of movement is now lost, and that we have to rebuild different visions of time.

Is all this formalism? Are we playing a minimalist card game? What remains of meaning, humanity, social commitment? The great achievement of Chris Ware is that his fiction also builds emotions, feelings, thoughts, concepts; in a word, everything which is typical of the human machine. The building material of the book is essentially autobiographical - the story of the lonely Jimmy Corrigan is mainly about an absent and impossibly present mother and an overwhelmingly present but absent father. But this material does not transform it into another “story of myself by myself,” the dominant feature of American adult comics since the sixties; rather, it underlines the universal dimension of its story.

Cite this essay

Baetens, Jan. "New = Old, Old = New" Electronic Book Review, 1 January 2001, https://electronicbookreview.com/publications/new-old-old-new/