On feminist futures of electronic literature (and interactive narrative, more broadly construed).

Introduction

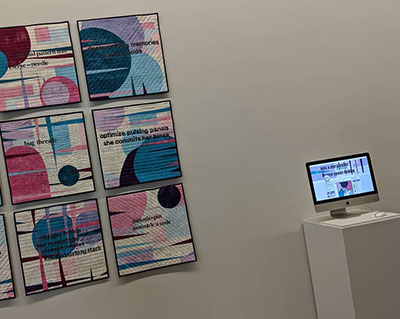

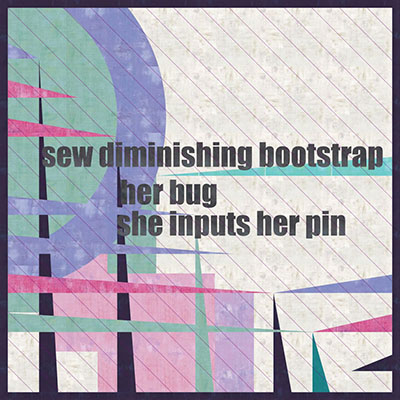

“Re:traced Threads” is a hybrid physical-digital work inspired by the discourse of computational craft. It is an installation piece that includes both procedurally-generated, ephemeral, digital artifacts of poetry (displayed on a computer monitor) and the physicality of handmade quilts (displayed on the wall). The project builds on the traditions of quilted poetry, which combines methods of applique and piecing with both written language and representative or abstract imagery, but using a digital, procedural source to guide the making. The project consists of two elements: a Twitter bot producing hypothetical works of quilted textual art, and a set of 9 blocks of physically-realized works patterned on selected output from the bot. The Twitter bot has been seeded with fundamental shapes and elements of quilt poetry, as well as a language library that draws on the verbs and words of fiber craft (a traditionally feminine-coded space of making) and computation (a typically masculine-coded space of hacking.) As a Tracery-powered bot, it will act as an unending source of inspirational imagery, with only selected generated image-texts chosen for the labor-intensive task of physical quilting. By fusing these sources and linguistic elements in procedurally crafted text poetry that is born-digital, but made “soft” by the act of translation to fiber and fabric, this installation draws attention to gendered making and the assumptions that frequently keep the discourse of craft artificially separate from communities and practices of digital making.

While the quilts and bot are coded by the installation’s author, this installation is conceptually collaborative in the inherent tradition of craft: the bot relies upon Kate Compton’s Tracery library, designed to make procedural drawing and writing accessible; the bot itself as the unpredictable combiner of visual and textual inspiration; and the author as the programmer of the grammar, curator of the bot’s output, and maker of the quilts themselves. As such, the work comments on the erasure of authors within both traditionally communal crafts and procedural spaces, inviting the viewer to engage with both the work and the discourse of making.

The potential of computational craft is disruptive, existing as it does at the intersection of STEM, arts, and humanities: “a focus on craft activities can lead to a re-evaluation of some of the basic concepts of traditional computer science: a ‘computational crafter’ may well begin to rethink the very ideas of programming languages, software engineering, computer architecture, and peripheral devices” (Blauvelt et al.). This “rethinking” is not inherently activist, but it does immediately bring that potential, thanks in part to the degeneration of craft in traditional discourse—even advancing craft as part of the umbrella of art is controversial. Fiber-based crafts such as sewing, quilting, weaving, and embroidery are particularly suspect in their inclusion in institutions, as they have been traditionally associated with women and thus with spheres of domesticity. In the preface to the classic history of embroidery The Subversive Stitch, first published in 1984, Rozsika Parker observes that “the art of embroidery has been the means of educating women into the feminine ideal, and of proving that they have attained it, but it has also provided a weapon of resistance to the constraints of femininity” (Parker). It is my interest in computational fiber arts as a “weapon of resistance” that drives the work of “Re:traced Threads.”

Craftivism and Feminist Making

“Re:traced Threads” draws on the history of craftivism, a form of expressive craft that Betsy Greer’s definition of craftivism focuses on “engaged creativity,” and focuses on craft as expression and communal action (Greer). By this definition, projects such as the Orlando Modern Quilt Guild’s outpouring of charitable quilts in the wake of the Pulse shooting (which targeted a center of the LGBTQ+ community) qualify as well as more overtly political work. For instance, the now-famous “pussy hat” knitting project, an exemplar of collective feminist craftivism despite lacking in inclusivity, demonstrates the potential of craftivism augmented by social networked media. As Shannon Black describes:

Although the strength and longevity of these networks is unknown, the Project encourages activism that is at once accessible and multi-scalar, functioning at the personal (i.e. making and/or wearing hats), community (i.e. the exchanging of hats), national (i.e. wearing and making hats at the Women’s March), and international (i.e. the making and wearing of Pussyhats at various marches throughout the world) levels, cultivating relationships and promoting participation in the spirit of political activism and change (Black).

The type of networked feminist work represented by the pussy hat movement is on the rise. Feminist crafting groups such as “Stitch’nBitch” demonstrate approaches to integrating technology in traditional crafting communities, and this type of space is growing both in prevalence and in political contention (Minahan and Cox). Such craft communities are already spaces of play, with socially mediated craft exchanges and rules-limited challenges just one example of prevalent “games” (Sullivan et al.). Contemporary subversive craft within online communities frequently engages in play with the very expectations of craft, embedding feminist discourse into the context of domestic making in a way that resists “traditional gendered domestic context” (Winge and Stalp).

Such communities have grown up alongside the networked communities of electronic literature, although their discourse has only occasionally intersected formally. Most notably, the potential for fusion of craft and computation in procedural electronic literature is demonstrated in Kathi Inman Beren’s work “Tournedo Gorge,” which includes a feminist commentary in the code: “I'm a code novice and intuitive cook. It delights me to mash the procedural with the domestic, female and tactile” (Berens). Other exemplars of playful fusions of data and computation abound in the craft community, although not always in conjunction with the labels of digital art or electronic literature. One of the more poignant is the rise of “Tempestry” scarves, which translate day-by-day visualizations of the temperature to colored knitted rows (McNeil). As one knitter, Kiki B. Smith, described the process in an interview: “I found this to be one of the most mindful projects I have ever done…each stitch, each row, a meditation on the climate, humanity, the Earth” (Schwab). Such data-driven craftivism, circulated as a form of nonfiction storytelling in Facebook communities, on Twitter, and on Instagram, offers a mechanism for personal, feminist craftivism through fiber making.

Carolyn Guertin has described the potential of networked feminism as hacktivism, observing that “when postfeminisms meet the new media they encourage these kinds of pleasures in the confusion of boundaries between bodies, texts, technologies, politics, and cultures” (Guertin). While one hopes that we are now decidedly post-“postfeminism,” the idea of networked feminism as crossing (and erasing) boundaries

Tracery as Craftivism

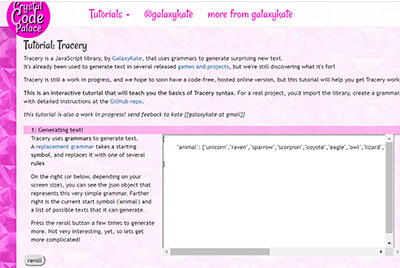

Tracery was developed by Kate Compton as “an authoring tool for casual users to build grammars to generate interesting stories” (Compton et al.). This emphasis on the casual user is unusual in procedural tools of any kind. Kate Compton’s own aesthetic puts an emphasis on the feminine and the playful, inviting the user into a style not typically associated with the space of computer programming. As shown in figure 2, the pink background immediately defies such expectations.

“Re:traced Threads” is one of many works of electronic literature powered by Tracery’s friendly grammar, which is made even more accessible thanks to George Buckenham’s companion tool “Cheap Bots, Done Quick!” . Twitter bots powered by this tool are part of what Leonardo Flores has termed “third generation” electronic literature. Flores defines this generation as “less interested in originality (a digital modernist characteristic), and more willing to create remixes, derivations, copies, and outright plagiarism of works, frequently adding personal touches and customizations” (Flores). Tracery (and Twitter bots more broadly) particularly embrace the ideas of remixes and derivations, and “Cheap Bots” even allows users to easily share their source code when publishing new bots (including “Re:traced Threads” itself).

The textual grammar of “Re:traced Threads” is fairly simple, and demonstrates some of the underlying accessibility of Tracery’s crafty approach. It relies upon a combinatorial fusion of computational and craft-related nouns and verbs:

craftNouns:[

album,

backing,

bargello,

barkcloth,

basting,

batik,

batting,

bearding,

beading,

betweens,

bias,

binding,

stitch,

nesting,

bobbin,

tension,

chainstitch,

emblem,

embroidery,

frame,

sash,

gap,

gapping,

hoop,

hooping,

lettering,

mirror,

monogram,

needle,

pantograph,

tape,

puckering,

punching,

density,

design,

thread,

broadcloth,

block,

border,

calico,

charm,

die,

flannel,

feed dogs,

paper,

sleeve,

foot,

fabric,

loft,

longarm,

medallion,

memory,

motif,

quilt,

fiber,

panel,

patch,

value,

unit,

seam,

fill,

facing,

hook,

scale,

satin,

punching,

button,

cloth,

pattern,

pin,

spool],

craftVerbs:[

appliqué,

bind,

sew,

hem,

bridge,

fill,

press,

back,

repeat,

rotate,

stabilize,

thread,

break,

cut,

tie,

trim,

verify,

glaze,

label,

layer,

piece,

corner,

connect,

rip,

mend,

make,

assemble,

combine,

mix],

codeNouns

:[algorithm

,application

,bootstrap

,code

,structure

,data

,framework

,stack

,query

,object

,function

,variable

,binary

,bug

,command

,conditional

,statement

,pattern

,server

,parameter

,grid

,pixel

,resolution

,user

,flow

,element

,repository

,comment

],

codeVerbs

:[decompose

,debug

,iterate

,control

,program

,run

,embed

,influence

,bounce

,optimize

,mine

,declare

,edit

,design

,type

,input

,reverse

,upload

,command

,commit

,break

,save

],

adjectives

:[failing

,falling

,diminishing

,dissipating

,rising

,growing

,pulsing

,flashing

,moving

,running

,shifting

,pending

]

Note that the JSON structure shown here can also be generated using a visual interface that eliminates the need for syntax, further increasing the accessibility The aesthetic code is more complex, working with web graphics (SVGs, or scalable vector graphics) at its foundation and using the same replacement vocabulary to interrupt those elements. I added certain constraints to harness the possible into the tangible, replacing the palette of HTML5 colors with scans of fabric so that the digitally-made (shown in figure 3) echoes the material artifact (as shown in figure 1).

Retracing Threads

These structures encourage a new way of thinking of the making of third generation electronic literature: as a craft, reliant upon patterns, but encouraging experimentation and the passing of knowledge through pattern-making, pattern-following, and pattern-breaking. The pattern is a feminist tool because it acts as a way of passing on knowledge: communities of pattern sharing online are themselves activist, encouraging the viewer to see themselves as a potential maker—in that sense, every fiber craft work released with its pattern in online communities is fundamentally “open source.” In the past, I’ve noted that the feminist futures of electronic literature (and interactive narrative, more broadly construed) are intimately tied to questions of code: who codes, and how, and perhaps most importantly how it is taught (Salter). With “Re:traced Threads,” that work becomes material.

Works Cited

Berens, Kathi Inman. “Tournedo Gorge.” Electronic Literature Collection Volume 3, Feb. 2016, http://collection.eliterature.org/3/work.html?work=tournedo-gorge.

Black, Shannon. “KNIT + RESIST: Placing the Pussyhat Project in the Context of Craft Activism.” Gender, Place & Culture, vol. 24, no. 5, May 2017, pp. 696–710. Taylor and Francis+NEJM, doi:10.1080/0966369X.2017.1335292.

Blauvelt, G., et al. “Integrating Craft Materials and Computation.” Knowledge-Based Systems, vol. 13, no. 7, Dec. 2000, pp. 471–78. ScienceDirect, doi:10.1016/S0950-7051(00)00063-0.

Compton, Kate, et al. “Tracery: Approachable Story Grammar Authoring for Casual Users.” Seventh Intelligent Narrative Technologies Workshop, 2014. www.aaai.org, https://www.aaai.org/ocs/index.php/INT/INT7/paper/view/9266.

Flores, Leonardo. “Third Generation Electronic Literature.” Electronic Book Review, Apr. 2019, http://electronicbookreview.com/essay/third-generation-electronic-literature/.

Greer, Betsy. Craftivism: The Art of Craft and Activism. Arsenal Pulp Press, 2014.

Guertin, Carolyn. “From Cyborgs to Hacktivists: Postfeminist Disobedience and Virtual Communities | Electronic Book Review.” Electronic Book Review, 27 Jan. 2005, http://electronicbookreview.com/essay/from-cyborgs-to-hacktivists-postfeminist-disobedience-and-virtual-communities/.

McNeil, Emily. “Tempestry Project.” Tempestry Project, 2018, https://www.tempestryproject.com/.

Minahan, Stella, and Julie Wolfram Cox. “Stitch’nBitch: Cyberfeminism, a Third Place and the New Materiality.” Journal of Material Culture, vol. 12, no. 1, Mar. 2007, pp. 5–21. SAGE Journals, doi:10.1177/1359183507074559.

Parker, Rozsika. The Subversive Stitch: Embroidery and the Making of the Feminine. I.B.Tauris, 2010.

Salter, Anastasia. “Code before Content? Brogrammer Culture in Games and Electronic Literature.” Hyperrhiz: New Media Cultures, 2017, doi:10.20415/hyp/017.e02.

Schwab, Katharine. “Crafting Takes a Dark Turn in the Age of Climate Crisis.” Fast Company, 11 Jan. 2019, https://www.fastcompany.com/90290800/crafting-take-a-dark-turn-in-the-age-of-climate-crisis.

Sullivan, Anne, et al. “Games Crafters Play.” Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on the Foundations of Digital Games, ACM, 2018, pp. 26:1–26:9. ACM Digital Library, doi:10.1145/3235765.3235802.

Winge, Therèsa M., and Marybeth C. Stalp. Nothing Says Love like a Skull and Crossbones Tea Cozy: Crafting Contemporary Subversive Handcrafts. 1 Feb. 2013, doi:info:doi/10.1386/crre.4.1.73_1.