Burdick situates the speculative software prototypes of Trina: A Design Fiction as design-theory hybrids that can expand our understanding of critical making and critical design. The essay offers four readings of the Trina prototypes, designed as research into speculative writing technologies that are situated and embodied. The essay concludes with the introduction of an “Indexical Reader,” a design concept for close and distant reading in the Humanities.

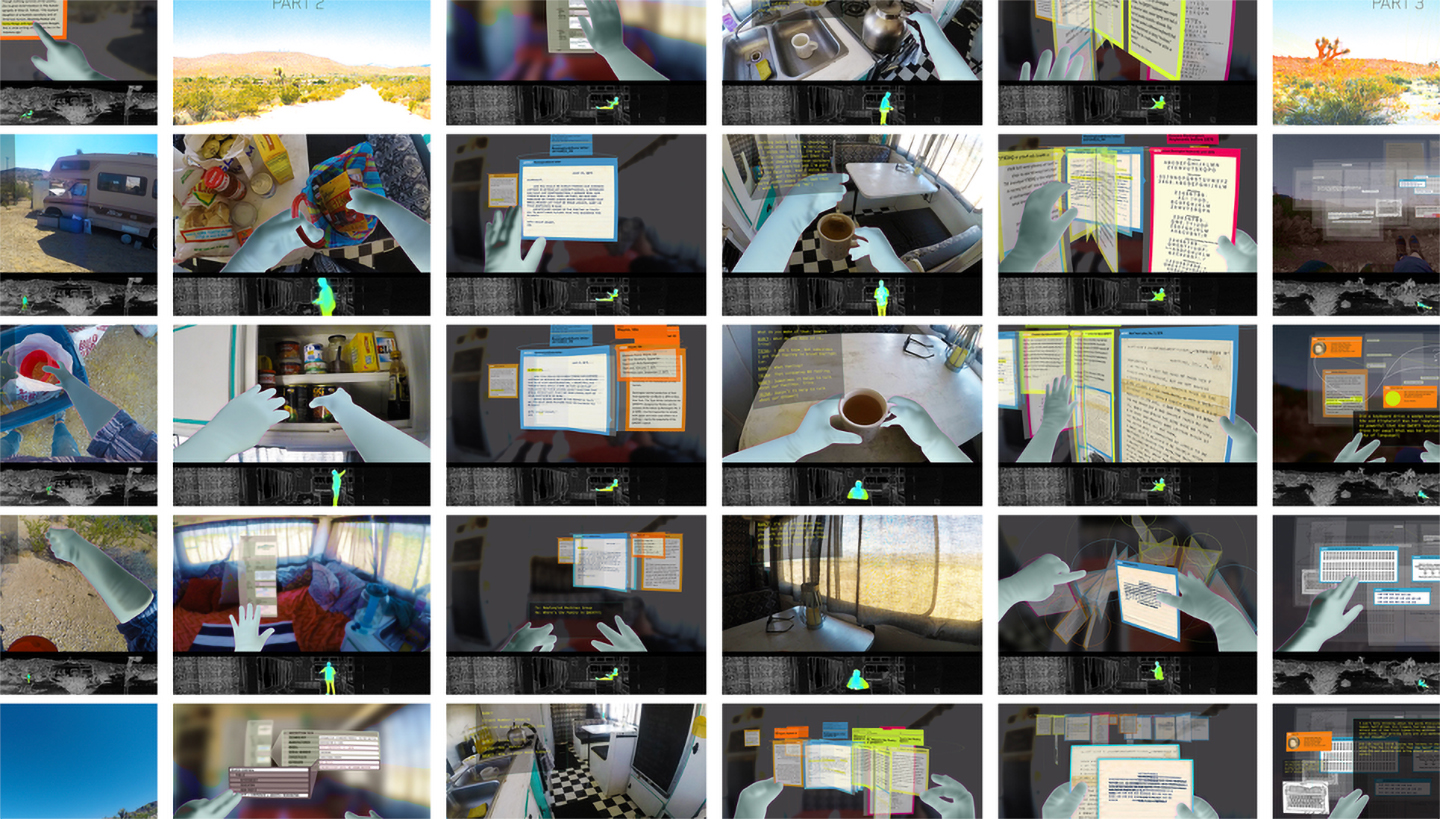

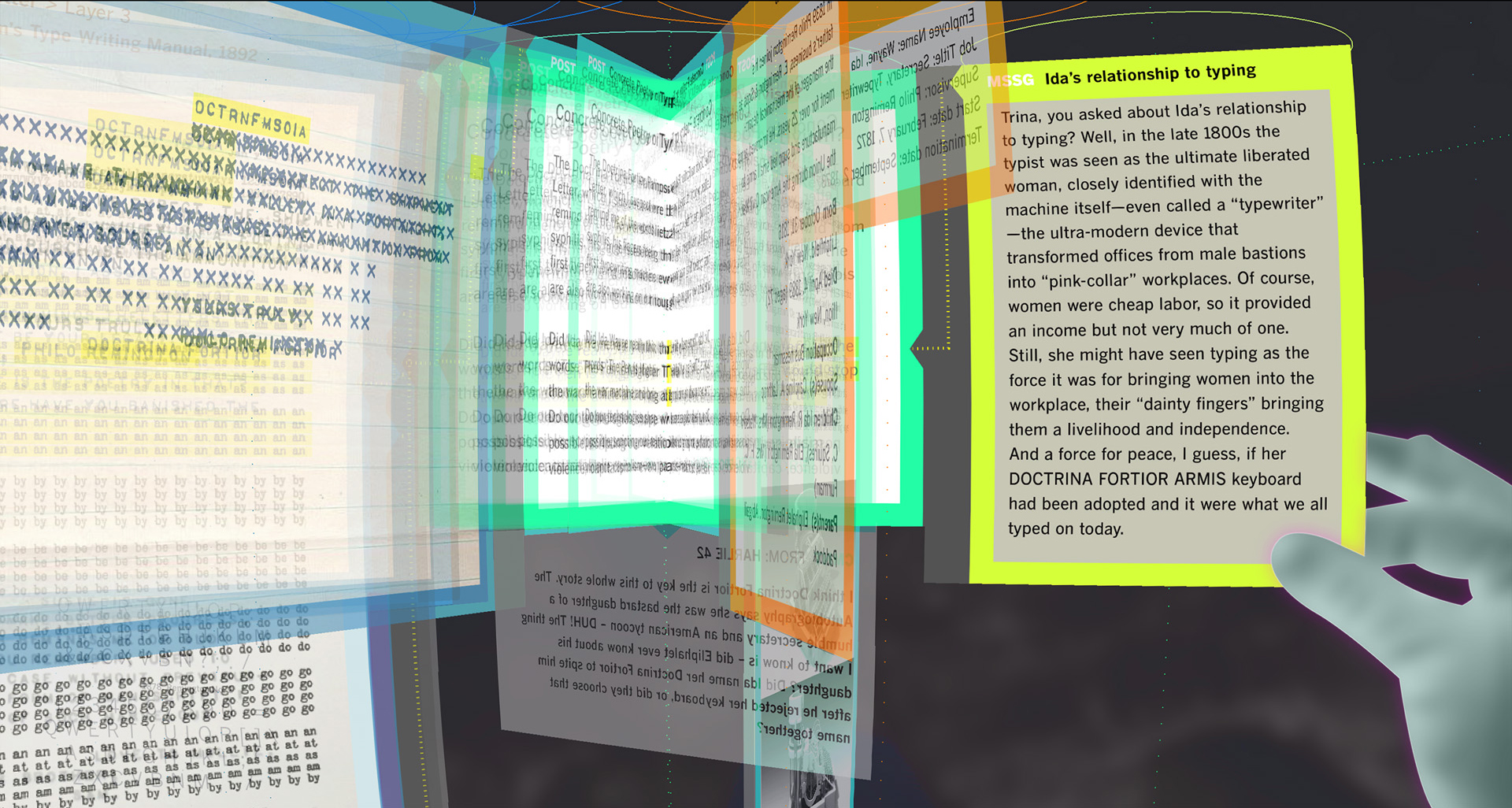

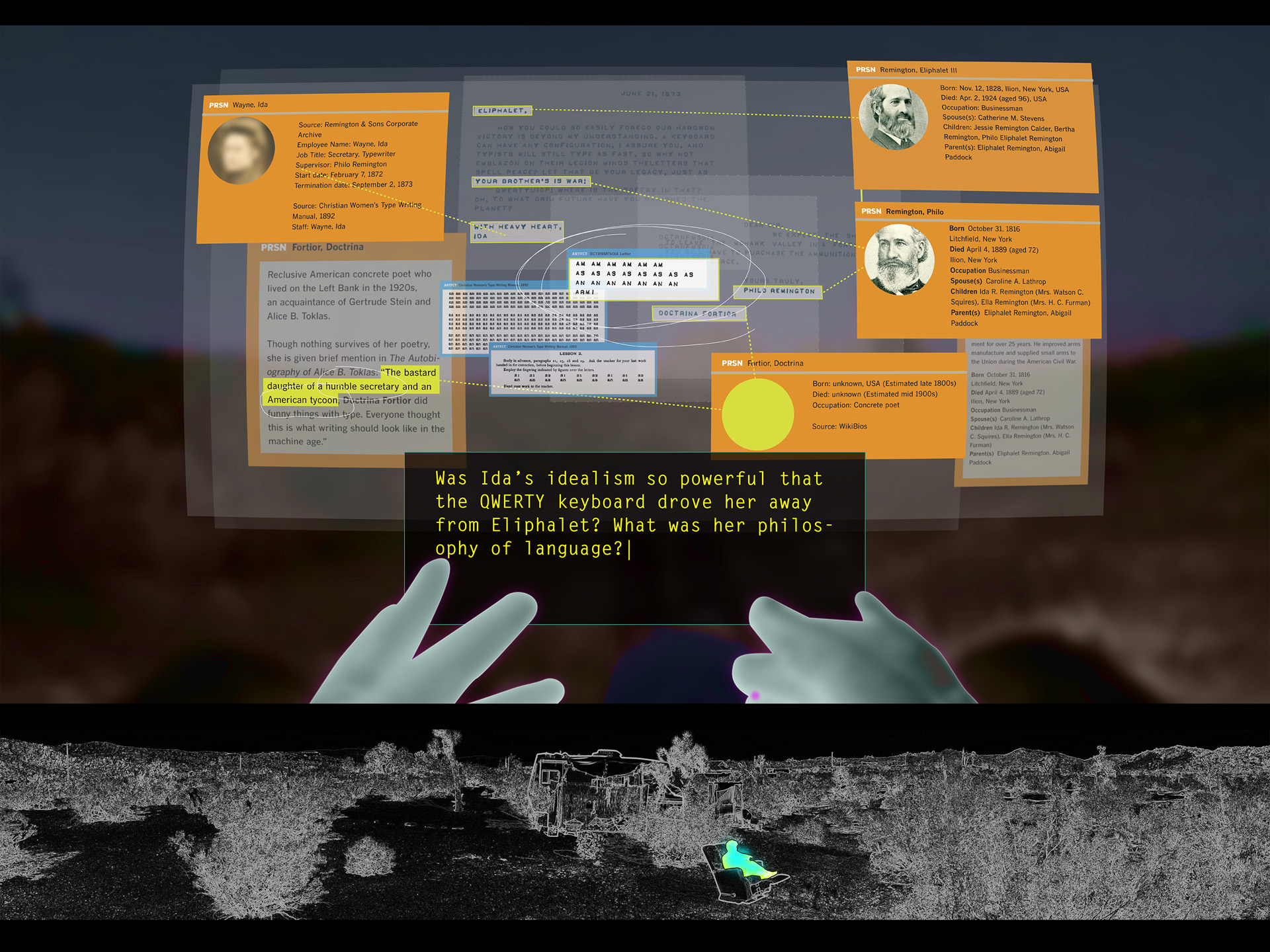

Trina: A Design Fiction brings together speculative computing (Drucker, SpecLab), speculative software (Fuller), and speculative design (Dunne and Raby) in equal measure. The story is a feminist reconfiguration of language, bodies, and writing technologies, co-authored by myself and Janet Sarbanes. In Trina’s collaged photo-graphics, text, image, and environment coalesce. We read/watch/listen as Trina traverses the gendered politics of typewriters and guns, Left Bank literary expats, and the personnel files of E. Remington & Sons, interrupted by perfunctory sessions with an AI therapist. The graphic story is told entirely through the interactions between Trina and her speculative software prototypes, designed in response to the research question that launched the project: “What might result when digital tools are designed from the ground up, based on the core humanities concepts of subjectivity, ambiguity, contingency, and situatedness? What new models of knowledge might they give rise to?”

While the project does not claim a specific answer to these questions, its pursuit through the creation of imaginary software allowed for the material experimentation and theoretical investigation of Research through Design (RtD). RtD is a methodology in which the activity of designing is posited as a mode of inquiry that results in new knowledge. The Trina story provided a design situation within which I could create a digital tool founded on key humanities concepts. The fiction defined the storyworld — the people, the conditions, the stakes — while a design brief established the technical and conceptual parameters of the software design, which led to the creation of multiple tools. This essay will look at the theory/practice interplay in the creation of the story’s speculative prototypes and how it can be seen to generate the “intermediary knowledge” of RtD which ties the abstraction of theory to the “ultimate particulars” of concrete design actions and outcomes (Höök and Löwgren). Through four distinct readings of the story’s prototypes, I will demonstrate how such design-theory hybrids can expand our understanding of critical making and critical design, concluding with the introduction of a design concept for multimodal scholarly work in the (digital) humanities.

Creative practice has always involved critical thinking. A theory-practice divide can be elicited when those engaged in “making” are asked to account for the critical and theoretical dimensions of their work, in writing. Practice-based design researchers are sometimes expected to produce research outcomes in the manner of the humanities and sciences where the circulation of citations, journal articles, and books serves as validation in national or institutional research assessment exercises. Such pressures have prompted design scholars to develop theories that account for “designerly ways of knowing,” hoping to identify and preserve qualities and practices distinct to design while incorporating textual production with intention and rigor (Cross; Stolterman).

Before going further, I should clarify here what I mean by “design.” I write this essay as a design scholar, educator and practitioner immersed within the design profession, discipline, and discourse. This is not the design that many people undertake on a daily basis nor is it the design thinking that has been described and practiced in other fields, from anthropology to business schools. I’m talking here about cap-D design, and within its specialized discourse, there are numerous competing definitions at play. The idea of design as a process of “rational problem-solving,” the analytical plans and methods of “design science” (Simon), has long dominated, permeating design rhetoric with four key concepts: individualism, objectivism, universalism, and solutionism (Rosner). While these notions have been used to justify design’s relevance to corporations and markets, they are at odds with the critical inquiry of the Humanities. A better fit can be found in Donald Schön’s “reflection-in-action,” a philosophy of practice in which design is seen as situational, improvisational, and difficult to codify; designers engage in a “conversation” with a unique design situation in which action is a way of knowing (Schön). Reflective practice brings to design the notions of contingency, subjectivity, and reflexivity. Similarly, design as social critique can be found in participatory, critical, and speculative design practices whose goals are cultural, emancipatory, political, and intellectual (Rosner). I rely largely on the latter two orientations which converge in my own critical reflective design practice.

In the essay that follows, I will introduce the main tenets of Research through Design (RtD) and its notion of intermediary knowledge as a site where theory and practice meet. It is this conjunction that brings the critical to reflective practice — and makes it relevant to this special issue of ebr and tdr. Then I will demonstrate how the design of the software prototypes in the Trina story were entangled with theory before, during, and after their creation, leading to a design concept that I call an indexical reader, at the ready for deployment in future instantiations or further theorization.

Theory/Practice in Research through Design

RtD arose as a form of practice-based research in the late 20th century and finds adherents across many design specialties from industrial design to human-computer interaction. RtD is concerned with how design-specific activities and outcomes can be used to generate new knowledge about design but also about other topics when used as a method in other fields. The RtD referenced throughout this essay is enacted through two aspects of design that reflect the term’s status as both verb and noun: designerly activities and the designed realizations that result. The “designerliness” of RtD is linked to what Erik Stolterman calls the “nature of design practice” in which designers create concrete responses to specific situations characterized by messiness, complexity, and incomplete information. Design activities and realizations deal with “the specific, intentional and non-existing… Design is about the unique, the particular, or even the ultimate particular” (Stolterman 59). Stolterman eschews a problem-solution framing, claiming that designers engage instead with problem-setting, active materials, and dynamic, unstructured conditions through a hands-on exchange —Schön’s “conversation,” but also Tim Ingold’s “correspondence” — with the situated and the tangible (Schön; Ingold).

RtD builds upon Schön’s epistemology of practice which differs significantly from the research paradigms of the sciences in order to account for more performative and action-oriented ways of knowing, particularly in “situations of uncertainty, instability, uniqueness, and value conflict” (Schön 49). As professionals respond to each situation’s unique dynamics they develop patterns of action and a “feel” for the push and pull of fluid conditions. Such tacit knowledge (Polyani) and experiential learning (Dewey) have been described as “first-order knowledge: subjective insights and understandings pertaining to particular situations” (Höök et al.). The recognized challenge for this work is documenting and articulating such first-order knowing into a “second-order” form that is useful to others.

While Schön’s analysis has been widely adopted within design scholarship, critics point to the need for a greater emphasis on reflection that accounts for the positionality of the designer. In other words, through which lenses do individual designers with distinct educations and personal and professional biographies “reflect”? This is an important question. With design researcher Shana Agid, I look to critical and cultural theory to frame issues of race, class, gender, and ability. Agid recalls feminism’s theory/practice nexus to bring political and intellectual analysis to Schön’s reflective exercise (Agid). Theory/practice allows us to resist the binary in which activities that are ostensibly of the head or mind — thinking, theory, reflection — are posited as distinct from those that are said to happen in the body — making, practice, action. It’s taken years for fields ranging from feminist theory to neuroscience to art to reorient our conception of knowing as situated and embodied. Theory/practice helps account for both/and ways of knowing and being, especially where design, the digital humanities, and research are concerned.

Tara McPherson references the flickering of theory/practice in early feminist film studies when filmmakers and writers were engaged in defining a new medium (McPherson). She models her own practice in media studies and the digital humanities on those scholar-practitioners who were engaged in making with/in a new medium while also writing in/about the new medium. McPherson claims that some insights may have never been made if members of that community, in particular Laura Mulvey, had not been shuttling between modes and media: criticism and theory were articulated through both writing and reflexive filmmaking.

Phil Agre’s critical technical practice, on the other hand, provides the rationale for keeping the activities of technical action and intellectual reflection distinct, given that each has its own rigor, challenges, and opportunities (Agre). “Some of these critical tools will draw on the methods of institutional and intellectual analysis that have served generations of philosophers, sociologists, and literary critics. Others may be responses, each sui generis, to the specific properties of technical work…” which for Agre is defined by productive “limitations and failures.” “…Research could proceed in a cycle, with each impasse leading to critical insight, reformulation of underlying ideas and methods, fresh starts, and more instructive impasses.” Reflection, for Agre, serves many of the same purposes as it does for Schön — identifying tacit norms, strategies, and theories implicit in behavior patterns, problem framings, and constructed roles. But Agre’s reflection is not embedded in the technical action, rather it is enacted in the reflective space of writing, largely informed by literary theory.

RtD grapples with similar tensions. Thus, the question of how to account for, document, and disseminate the knowledge claims of RtD drives much of the methodology’s development. Within the literature, one can find ways to build theory from designed realizations as objects of knowledge but also from the tacit knowing of reflective practice made explicit (Durrant et al.; Höök et al.). Others have proposed that extrapolating the broad generalizations of theory from the ultimate particulars of design instances may be too big a stretch. Instead, they propose a kind of intermediate-level knowledge that “is more abstracted than particular instances, yet does not aspire to the generality of a theory” (Höök and Löwgren 24). By occupying the middle ground, intermediary knowledge, which can be discursive, artefactual, or a combination of the two, can be in dialogue with higher level theories while being tested and developed in particular designed instances. Intermediary knowledge is thus aligned with the kind of theory that design researcher Bill Gaver expects from RtD, theory that is “provisional, contingent and aspirational” rather than “extensible and verifiable” (Gaver 2).

In creating Trina, I worked through various mixes of theory/thinking/reflection and practice/making/action. My aim here is not to argue for one combination or sequence over another, but to demonstrate how design — action entangled with critical reflection, aware of its own construction and positionality, explicit about its theoretical orientation — can operate as a mode of inquiry that results in new knowledge. Thus, what follows are four distinct readings of the software prototypes of Trina. The first three readings exploit the elasticity of the term prototype in the context of RtD designerly activities. Specifically, the prototypes can be seen as: technosocial when framed as diegetic and performative; reflexive when undertaking the mission of speculative software; and embodied when in dialogue with media archeology. The fourth reading looks at one of the project’s designed realizations, the Commons Reader View, as a conceptual prototype, to generate new interpretations and possibilities beyond its use in Trina. What began as a response to the ultimate particulars of a design fiction will be worked into a design concept called an indexical reader.

Technosocial prototypes — from diegetic to performative prototypes

“Diegetic prototype,” is a term that is used widely in theorizing design fictions (Bleecker; Sterling). As coined by film theorist David Kirby, a diegetic prototype is used “to account for the ways in which cinematic depictions of future technologies demonstrate to large public audiences a technology’s need, viability and benevolence.” (Kirby, 2010, p. 41) A diegetic prototype enters the social sphere when its use and consequences are demonstrated within a story and its world (consider the interfaces in Minority Report or Avatar), which for Kirby serves as a kind of future tech public relations. I see Trina’s digital tools as diegetic prototypes in this sense, but also, with Kirby, I was inspired by the “performative prototypes” identified by Suchman, Trigg, and Blomberg (2002) in their ethnomethodological account of information technology development practices in a large corporation. In their study, they assert that a prototype’s meaning evolves through interactions amongst an assemblage of actors that can include people, a physical environment, management systems, the prototype itself, and more. Placed in a use context, the prototype is a working tool, a mock-up of a proposed future technology produced as part of a design process. The prototype acts as a “tangible, but also provisional, apparatus,” and a “reflexive probe.” I have discussed Trina’s prototypes as both diegetic and performative prototypes in the storyworld of a narrative-based design fiction, in depth, elsewhere (Burdick, 2019). What is important to identify here is how the prototypes of Trina were created “as part of a dynamic assemblage of interest, fantasies, and practical actions, out of which new socio-material arrangements arise.” (Suchman et al. 175) I interpret new socio-material arrangements as new practices, shifting the emphasis away from “discrete, intrinsically meaningful objects” and onto relations and actions (Suchman, Located Accountabilities in Technology Production). Suchman critiques the notion that the human subject is an autonomous actor and looks instead at how “relations of human practice and technical artifact become ever more layered and intertwined.” Designing software prototypes with this in mind pushed my attention away from the development of a future technology and the worlds it might promise, and onto the specific forces of Trina’s world(s) in giving shape to the use and meaning of her digital tools.

Reflexive prototypes — speculative software

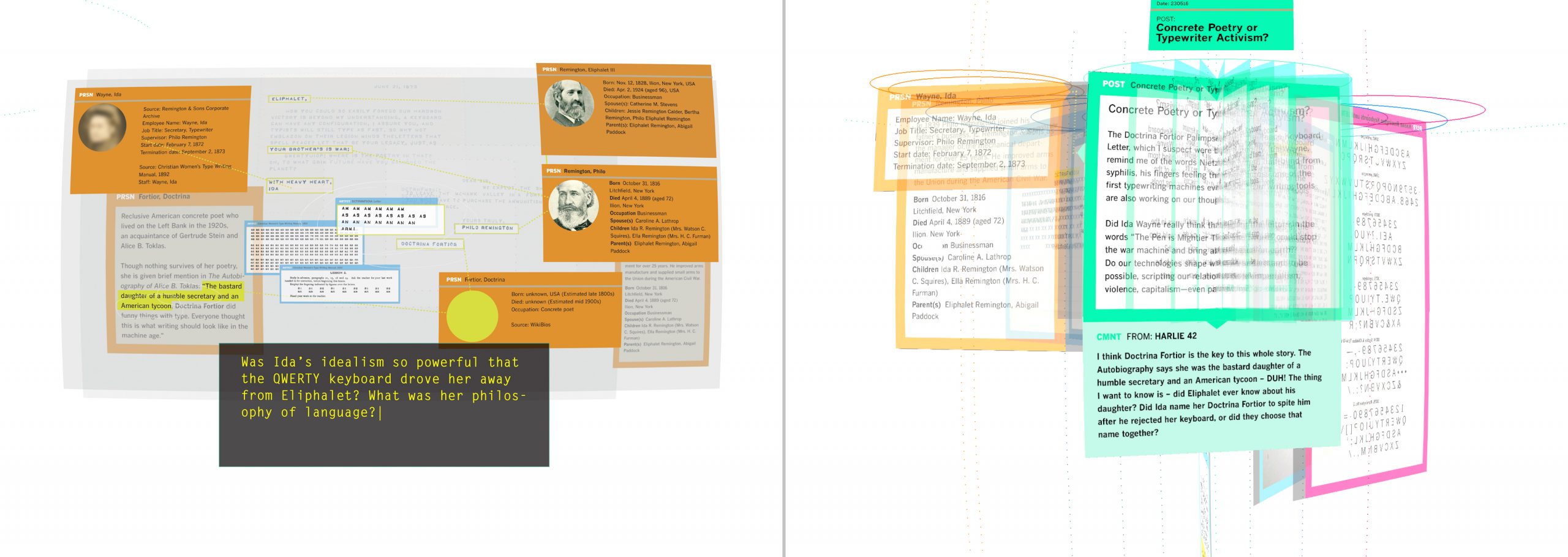

Throughout the design process, I also wanted the prototypes to take on the challenge posed by Matthew Fuller’s definition of speculative software, “whose work is partly to reflexively investigate itself as software. Software as science fiction, as mutant epistemology,” (Fuller 30). Fuller advocates for software designed to rework the events, regimes, and processes of software — cultural critique embodied in an interface. Like some strands of critical design, such works operate by upending naturalized expectations through subversive strategies that defamiliarize, their strangeness positioned outside the status quo and the ordinary everyday. But as part of a larger storyworld, Trina’s software had to perform as if it were created to be used on a daily basis, to accomplish ordinary tasks, forcing me to develop a different critical strategy than estrangement. Initially the software was designed as a single, integrated system in which the movement between research tools, information environments, and social networks would be fluid. While this might have been technically feasible, as speculative software it was conceptually untenable. The seamlessness masked the operations of the digital tools which went against the need for surfacing a critique of the software’s constructedness. Thus, what we find in Trina is not a single work of “mutant epistemology,” but a collection of interfaces that allow for a kind of comparative study of software ideologies and models of knowledge. My aim was to demonstrate that there is no such thing as a “default view,” rather all software constructs distinct user/subject positions, and allows for different kinds of agency for humans, data, networks, and systems of control.

Providing comparative software environments allowed me to draw the reader’s attention to the differences in visual form, organizational logic, data structures, interaction modes, user/subject positions, and networked relations of each. Within the story, each application became a character, a proxy for unseen forces, with a way of being and a way of knowing. The applications also became forces within the plot that Trina worked with and against on par with other environmental factors such as a group of amateur historians, the desert fauna, or the nearby Marine Base.

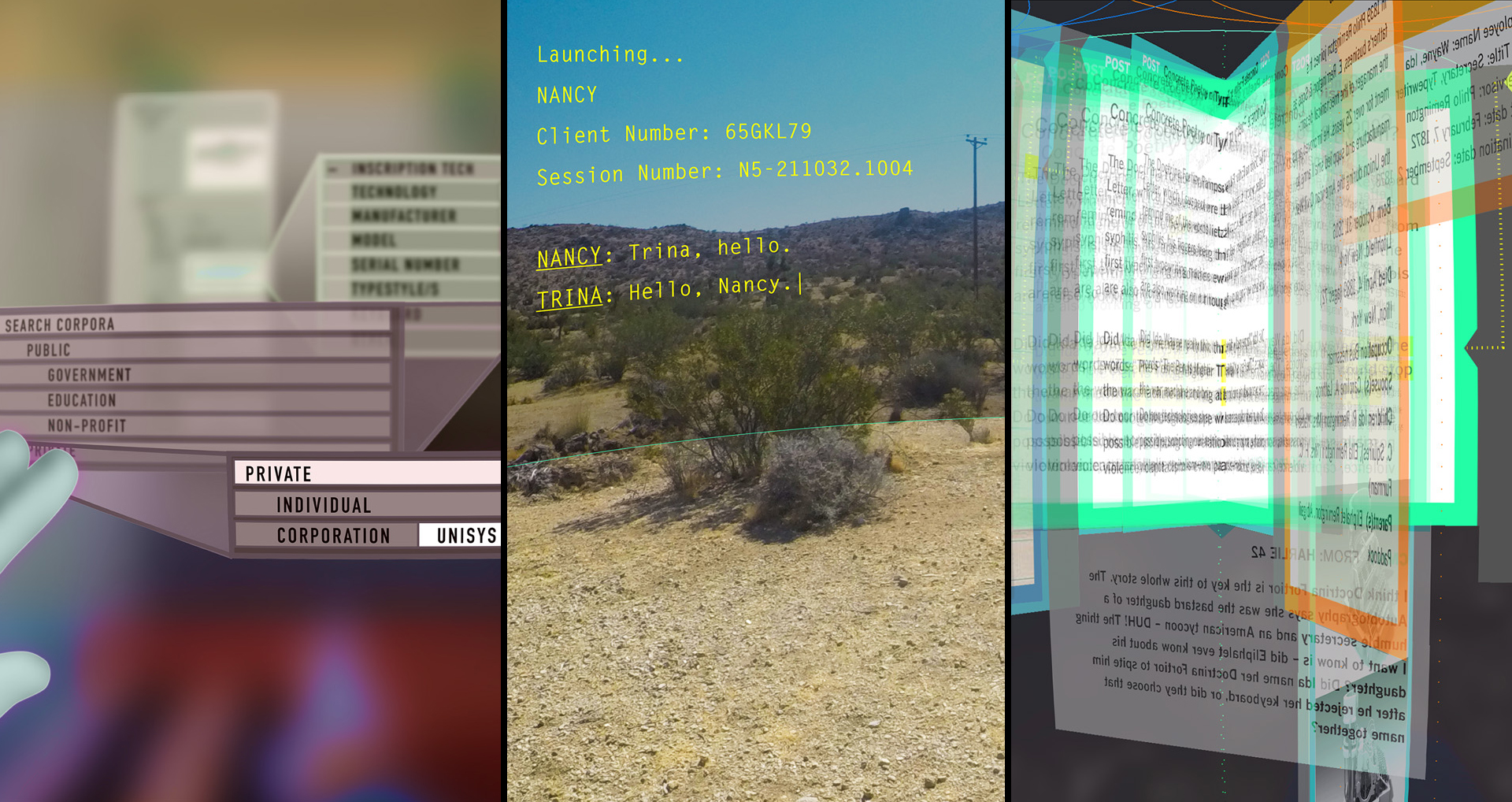

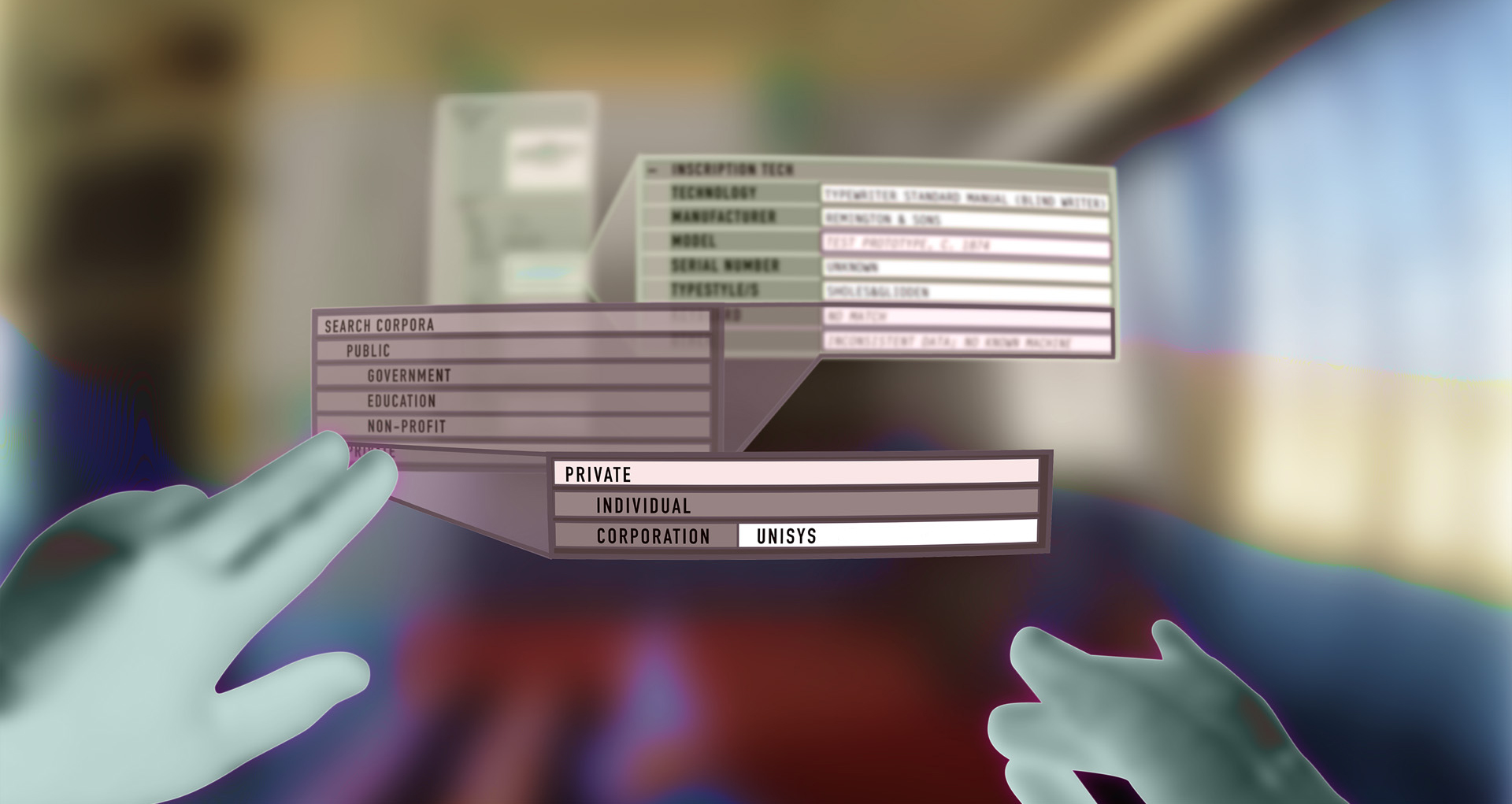

This critical orientation is manifest in the design of each prototype through its visual style, organizational logics, and mode of address. Analyssist (Figure 4) is only interested in forensics, provenance, and pinning down meaning. Its epistemology locates truth in evidence and facts. The interface explicitly visualizes its nested hierarchy of boxes within boxes that situate the user as task-oriented, filling fields provided by a master algorithm. In this regard, Analyssist is no different than the interfaces used by workers in fulfillment warehouses, or in even less robotic circumstances such as, say, the record-keeping of universities or health care providers.

By contrast, the AI therapist NANCY (Figure 5) is based on a psychological model of the individual in which self-knowledge and well-being is attained through talk and behavioral therapy. Thus, NANCY provides a two-way dialogue with an emphasis on the words spoken. The utterances are recorded and presented back to the user but they also sit in an HR file deep inside the corporation. NANCY’s design references ELIZA, one of the earliest natural language processing programs created at MIT (“ELIZA”), though contemporary AI is far more sophisticated, measuring responses in microgestures and deep linguistic analyses. The tone and vernacular of NANCY’s conversational user interface might signal the software’s outdated status, a perfunctory litigation-avoidance tactic on the part of the corporation. But it may also be that the feature is designed to disarm cynical users while it conducts other forms of surveillance.

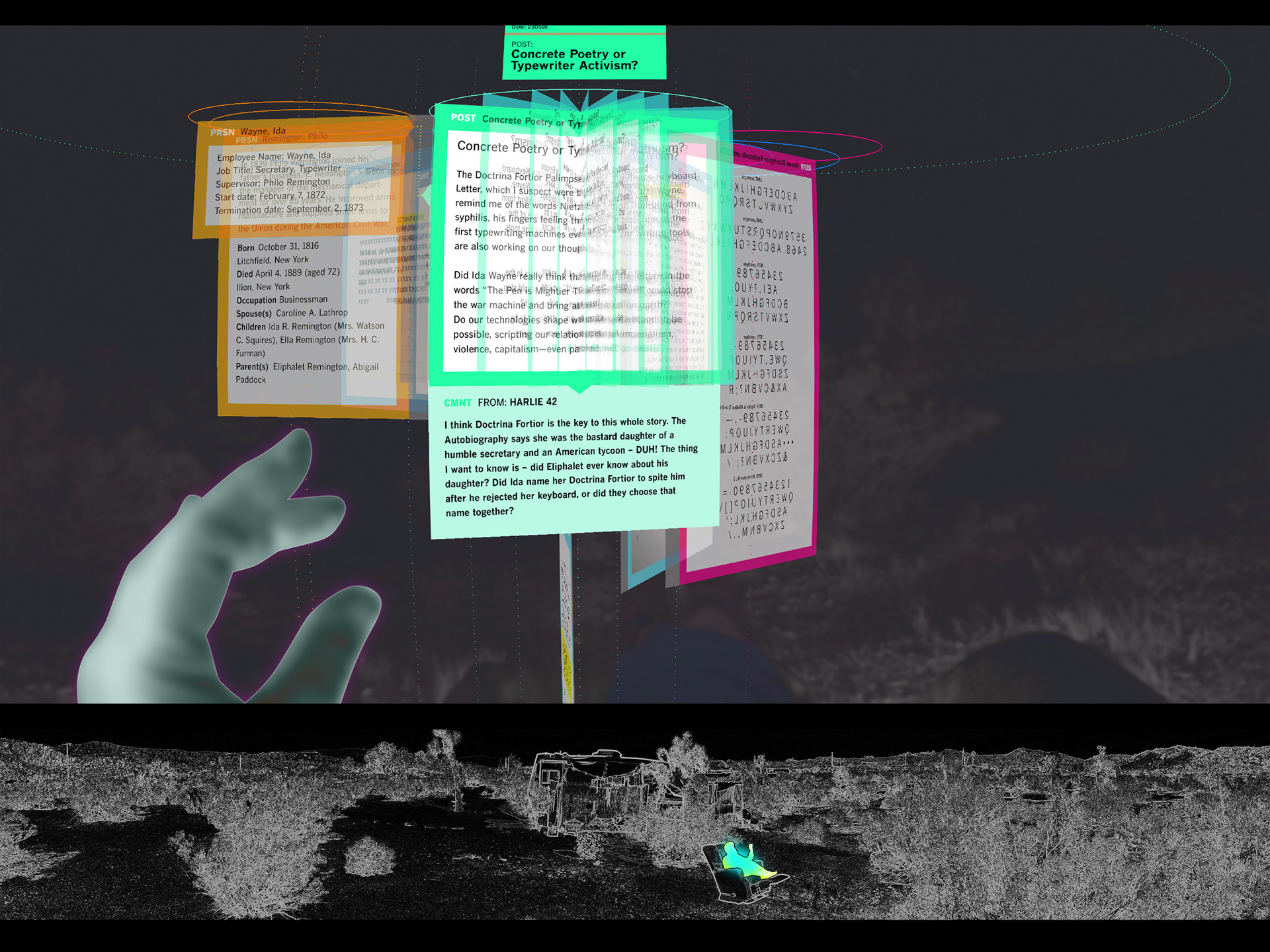

The Commons (Figure 6), on the other hand, sits outside of corporate control structures, and is built upon a model of knowledge that is partial, situated, contingent, and multiple, embodying the humanities-inflected values of open access and debate. This orientation can be seen in the design of the software’s Reader View in which multiple interpretations of a single document are always visible, arranged around the axis of individual “spindles.” The user is conceived as a reader/writer who controls which aspects of the larger collection are shown, and when. Pathways emerge as readers follow lines of thought co-created with fellow reader/writers. The visual emphasis is on multiplicity and connectivity in a non-hierarchical horizontal landscape. We will return to Reader View prototype in the fourth reading.

Embodied prototypes — media archeology

Designing digital tools for readers and writers provided me the opportunity to think/design through how technologies operate in concert with language and the body. As I was developing the software, I was working through readings in media archeology, among other fields, while also reflecting on my own experiences as a writer and a graphic designer. I was using media archeology as “a method for doing media design and art” (Parikka and Hertz).1My focus here is on prototypes. In Scenes of Writing, I discuss how to address the “human” in human-computer interaction when designing technologies for subjective and idiosyncratic acts of interpretation. See (Burdick, “Scenes of Writing”).

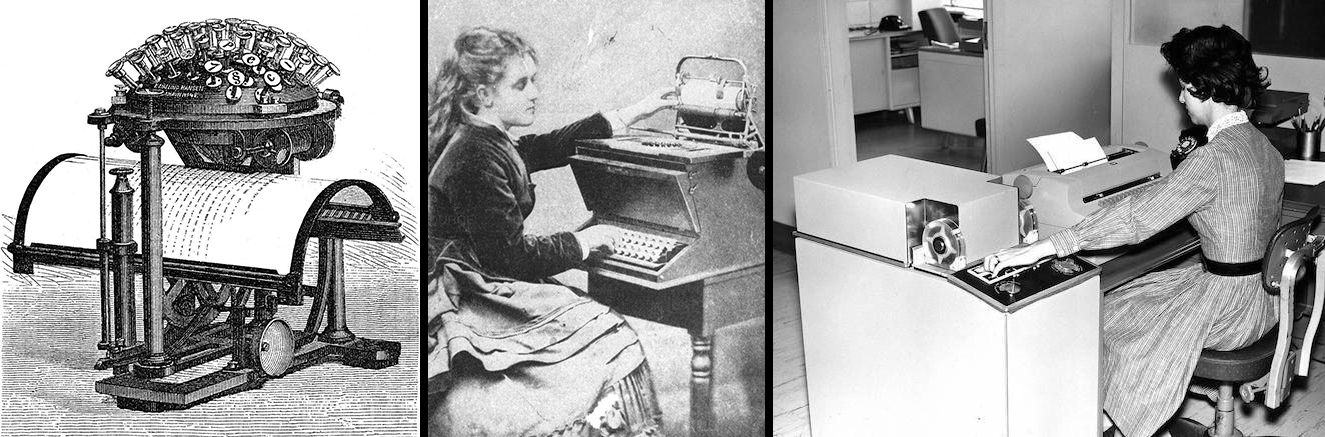

Through Friedrich Kittler’s account of Nietzsche’s famous proclamation, “our writing tools are also shaping our thoughts,” (Kittler 200) I came to understand how handwriting had required eyes as much as hands. Working with one of the first mechanical type writing machines, Nietzsche, who was going blind, did not have to see in order to get letters to align; the machine placed the marks one after the other, which meant that what appeared on paper could later be read by a human reader. Like many of the first typewriters, the machine was called a “blind writer” because even a fully-sighted person could not see the writing it produced until the paper was pulled from behind the machine’s apparatus (see Figure 8, left). Shortly after their introduction, typing machines were reconfigured to place the letter marks within the typist’s line of sight. But trained typists learn to type without looking, programming their fingers to feel the keys and memorize the QWERTY sequence. After taking typing in high school, reading was ruined; I no longer saw word shapes, I saw letters and spaces. The flow of reading that had taken me many years to attain was disassembled as my fingers silently tapped the letters of every word I saw, in every situation, on my denim-covered thighs until sometime in my mid-twenties.

Kittler introduced me to the history of the gendered definition of a “typewriter,” which calls forth all the women who have been called not only typewriter, but also computer and calculator, at first doing the work with their minds, eyes, and hands, and then, working the machines for the men. This prompted me to pay closer attention to bodies and the role they play in writing. Imagining the technology prototypes through Trina’s hands and eyes gave me a way to design that was both situated and embodied. Creating the prototypes allowed me to get a feel for how interactions and subject positions are entangled with biological and cultural material in answer to Suchman’s call to consider “specific configurations of persons and things … within social histories and individual biographies” (Suchman, Human-Machine Reconfigurations 284).

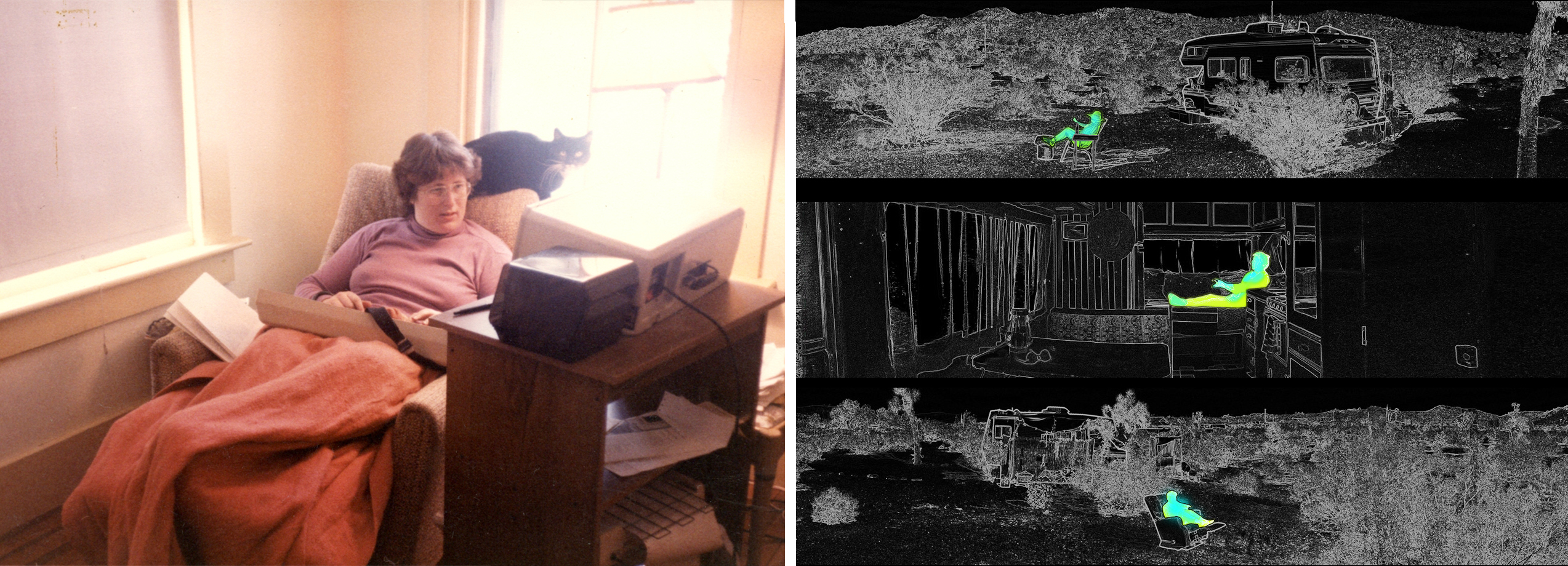

This is not to claim anything generalizable from Trina’s distinct writing habits, for writing can be decidedly idiosyncratic. In his study of word processing software in literary practices, Matthew Kirschenbaum looks at how the word processor is understood as part of a medial pro-cess, one of the many different writing technologies, old and new, that are configured by writers as part of their own individual working scenarios (Kirschenbaum). Writers can be found who write by hand, who commission bespoke digital tools, or who work for decades with applications and machines that they never update lest they disrupt a delicate scene. Kirschenbaum quotes Paul Auster, who still makes use of a typewriter, harkening back to my own experience in high school: “You feel that the words are coming out of your body and then you dig the words in to the page ... I call it ‘reading with my fingers’” (Kirschenbaum 21). Every writer’s setup is different, though many might resemble the image of Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick tucked into her recliner, cat on her shoulder, keyboard in her lap (Figure 9, left). You can see in Trina’s writing situations how physical comfort — pillows, footstools, food and drinks — are an integral part of her own writing ritual.

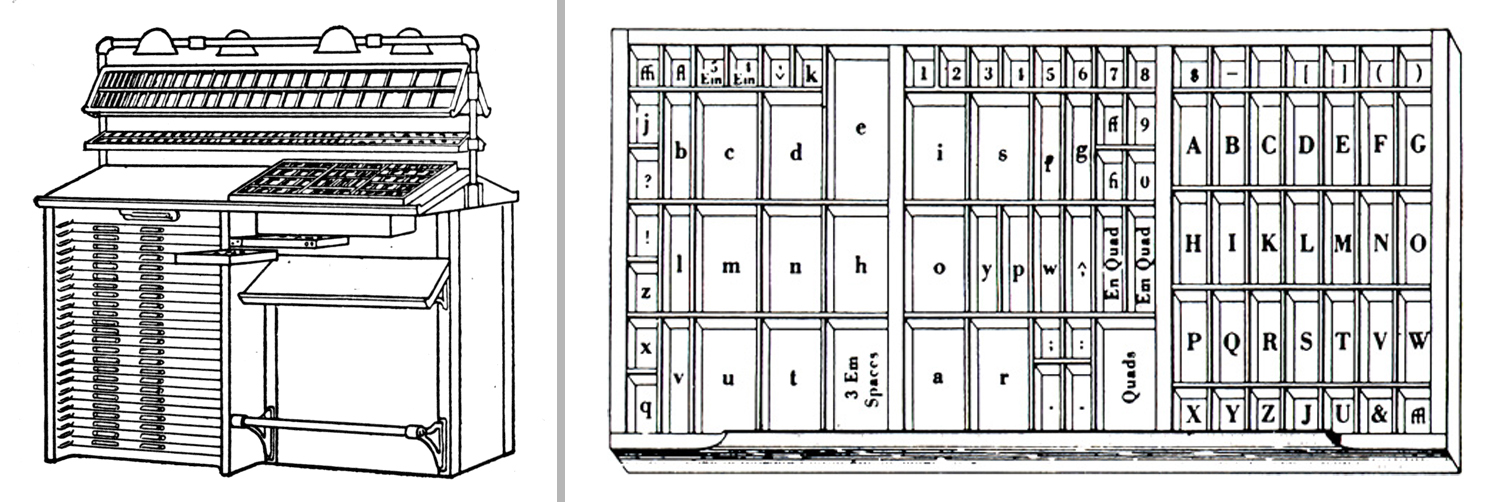

My understanding of a writing technology prototype as the nexus between language and the body is also informed by my experience in a letterpress workshop. Amongst the letterpress printing presses and lead type stands a tall piece of furniture, a technology called a compositing table that is used to arrange lines of metal type in blocks for printing, similar to that shown on the left in Figure 10. The position of various working surfaces and spaces implies the upright body of a human compositor: a manuscript can be attached at eye level; the type case is placed waist-high with a compositing table just above it, level with the hands; a well-worn footrest sits a few inches off the floor, ready to receive feet.

But it is the layout of the type case, a compartmentalized wooden box used for the storage, access, and retrieval of movable type, whose design is equal parts language and body. An example is the California job case (Figure 10, right), which took its name from its San Francisco origins and was widely used across the United States in the 19th century (“California Job Case”). The layout contains 89 compartments, for capital and miniscule letters, spacers, ligatures, and quads, which were laid out to reduce the distances that a compositor’s (right) hand would have to travel while composing lines of type. The spatial positioning and size of the boxes for each letter were allocated according to the frequency of their occurrence in the language. So, for example, in English, “e” appears most often — biggest box, top center — while “z” occurs the least — small box to the side. The bottom portion of the case, as shown in the image, is closest to the compositor. Two of the most frequently occurring words — “and” and “the”—are created through smooth gestures that start at the body and sweep forward. Thus, the case can be seen as a kind of indexical interface between human bodies and written language. Accordingly, different languages and different bodies demand differently mapped cases.

The history of the development of the QWERTY keyboard reveals a logic of a different sort. While the most prevalent stories involve rational responses to tangled keys, letter frequencies, and/or finger strength, the reality may be much sloppier. Yasuoka and Yasuoka assert that many of the conclusions made by contemporary historians have been based upon analysis that relies upon a 4-finger typing method. Yet the team asserts that early keyboarding methods actually involved only three fingers. By assuming a 3-finger position, a researcher was able to demonstrate the shortcomings of historical reconstructions and assumptions about hands, fingers, and letters (Yasuoka and Yasuoka). Yasuoka and Yasuoka instead piece together a history of the keyboard arrangement as a combination of remediating the telegraph, tweaking letter placement to avoid patent infringements, and other situational variables. The result is an unintuitive keyboard that requires hours of practice to learn to use quickly (high school typing, again). Through its institutionalization in typing schools, exercise manuals, and more, this illogical configuration persists. Indeed, the endurance of QWERTY is frequently used as an example of path dependence (David). “A path-dependent sequence of economic changes is one of which important influences upon the eventual outcome can be exerted by temporally remote events, including happenings dominated by chance elements rather than systemic forces” (David 332).

Science and Technology Studies and media archeology can serve as inspiration, guide, and provocation when creating imaginary software that takes into account the skeumorphs, legacy systems, path dependencies, and other forms of tech remediation that shape our contemporary technological environment. The prototypes and stories that result can make palpable such historical accounts and theoretical concepts. In the Trina story, the character Ida Wayne aspires to encode a pacifist message into her keyboard in a mystical gesture that is no less reasonable than Nietzsche’s proclamation Trina’s FingerTyps allow for blind writing and while she is seen in Slide 55 (Figure 11, right) reprogramming an alphabetic sequence into her finger sensors, is the practice any different from the way in which I programmed QWERTY into my teenage fingertips? Trina’s augmented reality display moves and reconfigures around her body rather than the other way around. No longer needing to stand at a compositing table or sit upright in front of a typewriter, Trina frequently reclines, propped up by pillows and a footrest. The only thing missing is a cat.

Conceptual prototypes — RtD Intermediary Knowledge

To address the design of the Commons software prototypes themselves, we can step away from the myriad forces at play in Trina’s storyworld and revisit the original research question of how to design digital tools founded on precepts central to the humanities. The Commons software was an attempt to answer this. The prototypes show a Reader View and a Writer View, two sides of an integrated system that allows for the reading, annotating, compiling, and composing of texts (Figure 12). For the purposes of this essay, we will look in depth at the Reader View, out of which I derive a form of RtD intermediary knowledge, a design concept called an indexical reader.

A design concept is a model educed from a specific instance — a concrete design situation — that is theorized and articulated so that it may be implemented in other contexts, without claiming to be universal. A design concept carries a core design idea that cuts across particular use situations and application domains. A widely used example is Alan Kaye’s early notion of a “dynamic book,” which can be understood as a kind of schematic abstraction that could be realized through a variety of different forms in different instances — an interactive museum installation, say, or a laptop — while still maintaining the integrity of the concept. A design concept is generative in that its aim is to advance theory and/or inform practice.

Design researchers have introduced distinct kinds of design concepts to study the push and pull of theory and practice in their creation. A strong concept begins and ends with practice. “A specific artifact is fully concrete, that is, not abstracted at all, and as such, it is (primarily) applicable only in the situation for which it was designed. Elements of that particular artifact, or instance, can be isolated and abstracted to the level that they are applicable in a whole class of applications, a whole range of use situations, or a whole genre of designs” (Höök and Löwgren 5). By contrast, a conceptual construct starts with and feeds back in to theory. The objective is to manifest “visionary theoretical ideas in concrete designs,” in order to advance theory (Stolterman and Wiberg 97). Designerly activities create a space for active reflection on theoretical concepts. Finally, a bridging concept moves fluidly between theory and practice, “often in a continuous process of theoretical and practice-based explorations, which is characteristic of many experimental design projects” (Dalsgaard and Dindler 1637).

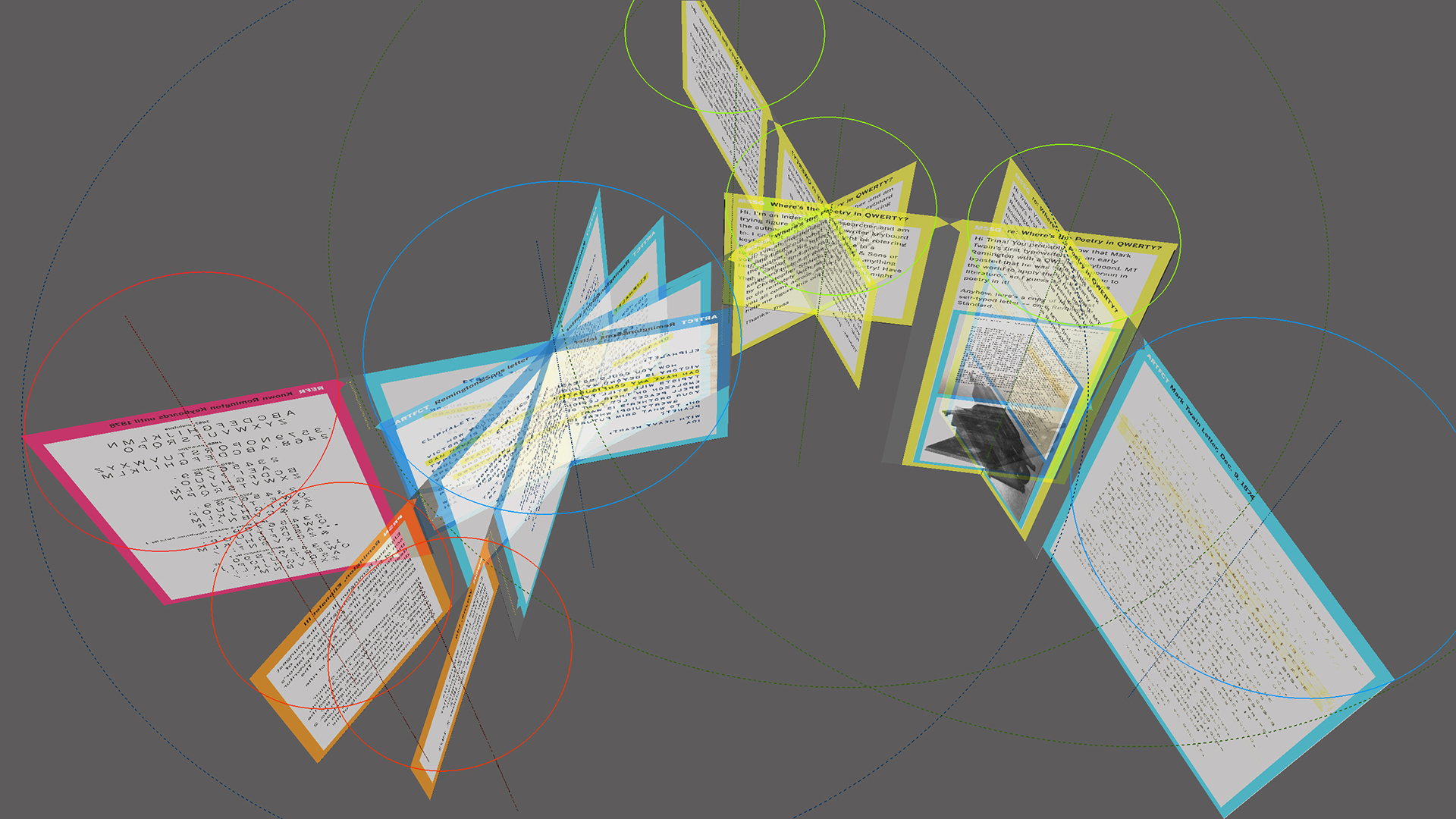

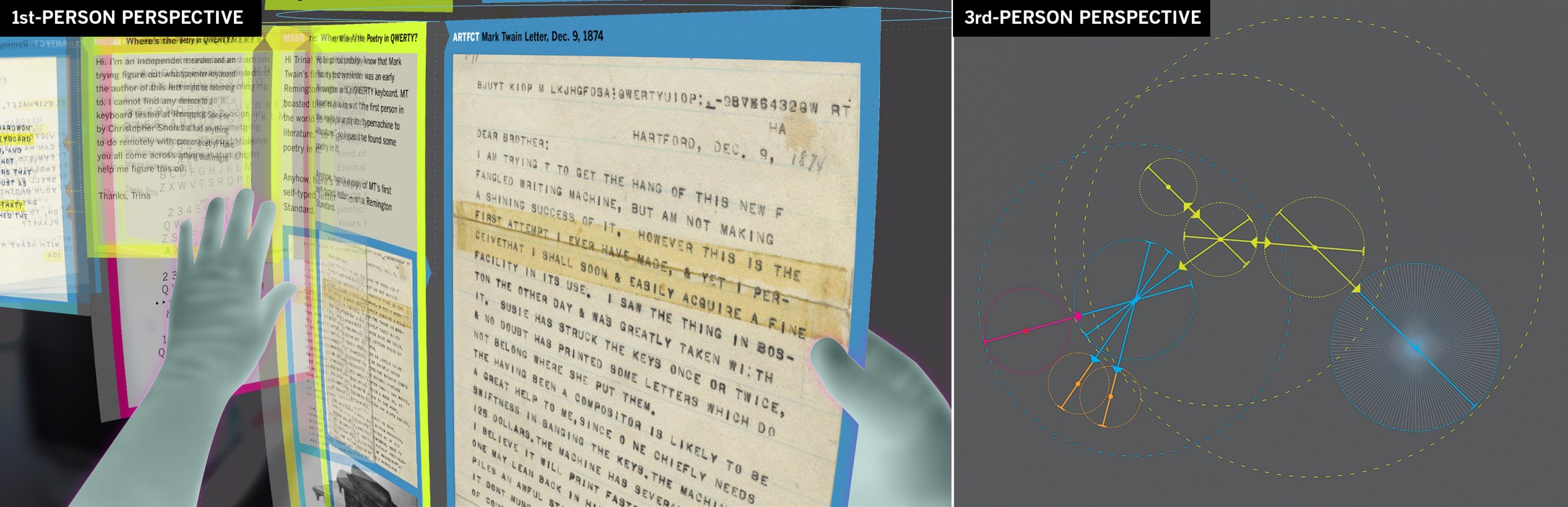

The Commons software resembles a bridging concept in its creation but a strong concept in its outcomes. The prototypes shown in the story were developed and tested for both technical and theoretical integrity in a variety of media and through ideas from literary theory, media studies, and feminist technoscience, in order to design digital tools “from the ground up, based on core humanities concepts.” What emerged through the RtD design process was an interface with a built-in duality that allows a reader to move inside and through texts when engaged in close reading (first-person orientation), then to switch to a position outside and above a collection of texts seen as a whole (third-person orientation), a form of distant reading (Moretti).

Here’s how it works. A reader in first-person orientation (Figure 14, left) begins with a document that automatically shows all its references in the form of a “spindle” that can be manipulated in virtual space. Each reference generates its own instantiation of the document, centered on the spindle, with a connecting document as an extension that sits to either its left (referring to) or right (cited by). Each instantiation appears semi-transparent, becoming opaque as the reader rotates the spindle or touches the pages. The reader can move from text to text, following the references, in what is referred to as citation chaining in library and information science. As the reader moves a new text to the center, that document generates its own array of incoming and outgoing citations and the cycle continues, slowly building a readerly terrain, a record of the reading experience.

But the reader can also pivot the entire collection, shifting to a third-person orientation in which the spindles appear as a kind of network graph whose nodes and edges are created by the documents themselves (Figure 14, right). The spatial arrangement of each reading session can be saved and shared. The logic of the displays are rooted in a data structure comprised of documents, relationships, metadata, and snippets (extracts), much of which is typical for textual analysis. But what is unique here is that the graph that is generated is not an abstract representation of numbers and relations, rather it is the actual side of the readerly territory itself. Each digital document thus has a dual identity, as the embodiment of a text to be read and as the trace of a document and its relations. It is this indexicality combined with the fluid movement between close and distant reading that defines the Commons Reader View.

The design of the Commons Reader View was in part a response to the affordances of virtual or augmented 3-D environments in which objects and spaces do not necessarily conform to real world physics. In the simulation software Unity, a virtual 3-D object, whether a coffee pot or a house, could be scripted to allow you to put your hand straight through its exterior walls. You could spin it around, float it in the air, or turn it upside down. You could also make it so big that you could stand inside it or make it so small that it could sit on the tip of your finger, while its shape and proportions would remain intact. By exploiting the object malleability and shifting perspectives of the software, I was able to create a reading apparatus that behaves in a manner beyond what is possible in the physical world.

The theoretical concepts that informed the prototype’s creation are manifest in several key features. The subjective and situated character of knowledge construction is realized in the simultaneous co-existence of multiple interpretations of a single document. The spindle structure was developed through early critical making exercises that worked through notions of n-dimensional textuality (McGann), readingwriting (Emerson), and visual epistemology (Drucker, Graphesis).2A full account can be found here: (Burdick, “Meta! Meta! Meta! A Speculative Design Brief for the Digital Humanities”). I was also inspired by artist Corinne Vionnet’s layered images of popular landmarks in which the subject appears as a blurry composite of viewer perspectives (Figure 15). The more numerous the number of interpretations, the denser the array and the fuzzier one’s view of the original becomes, an aspect built into the design of the Reader View. The contingency of interpretation, another key humanities tenet, is enacted through the experience of reading, selecting a specific perspective among many, and moving along a path created through cross-references and dialogue within and between the texts themselves.

*

While the design of the Commons involved such theory/practice interplay, turning the finished prototype for the Commons Reader View into a RtD intermediary knowledge claim requires an additional layer of interpretation. In the RtD literature, the process calls for “horizontal grounding,” in which a design concept is compared with others, and “vertical grounding,” in which it is connected upward to theory and downward to particular instances. Dalsgaard and Dindler claim that a design concept must be articulated, theorized, and situated, to maintain the rigor of a knowledge claim.

A design articulation identifies a concept’s key expressive qualities:

An indexical reader is a three-dimensional spatial-informational concept manifest as an object that can be engaged at different scales and from different positions, each of which reveals something about the structure’s parts and whole. An indexical reader has a built-in duality in which a view of the whole from the outside shows the intellectual organization that is experienced across space and time from the inside as meaningful relationships amongst its parts. The Commons’ Reader View, designed for use in a digital humanities context, allows a user to shift easily between close reading and distant reading. It is but one form that such a concept could take.

Theoretical connections define a design concept’s conceptual terrain. To locate the term indexical reader, I begin with Shannon Mattern’s notion of an “indexical landscape” which she used in a public lecture in 2010 to describe a space that is shaped “to refer to its own organized content and operative logics.” Libraries, grocery stores, and fulfillment centers whose shelves are arranged according to different systems of categorization for ideas or products can be thought of as indexical landscapes. Equally relevant is Johanna Drucker’s writing about visual epistemology and the way in which schematic graphical forms construct meaning. Like Mattern, Drucker is interested in forms in which the shape “…of its organization and the intellectual structure it represents are the same” (Drucker, Graphesis 111). Indexicality in architecture is located in strands of modernism related to both rationalism and functionalism in which “structure, function, and expression supply concurrent, co-existent knowledge” about a building (Zimmerman 277).

Indexicality in this regard relies on Charles Sanders Peirce’s notion of the index, a topic of recurring interest in film, photography, and media studies. Throughout his late nineteenth-century writings, Peirce defined three kinds of signs: icons, which look like the thing they represent; symbols, whose meaning is created through repeated associations; and indices, which rely upon a physical connection to the thing represented (Peirce et al.). Indices come in two forms: a physical trace, such as a footprint, weathervane, or sundial, that indicates the presence that made it; and a pointer, such as “this,” “there,” “now,” “I,” or “her,” which is defined through a speaker’s position in space and time. In both cases, the index is largely seen as being grounded in the real. Indeed, the immediacy and evidentiary qualities of mechanical photography have been attributed to such an indexicality, though digital imagery has complicated matters (Doane).

Critiques of data visualizations as the reduction of literary semiosis to numerical abstraction bemoan the erasure of contingencies and actualities. Might indexicality restore such a loss? Or at least reconfigure it? The network graph of an indexical reader is constructed through a combination of digital documents, data structures, algorithms, and interface design. As a digital object, it is intrinsically quantitative; as a graphical display, it is interpretative. Through human interactions with an algorithm, it is performatively synechdotal, complicating the distinction between mathesis and graphesis (Drucker, “Digital Ontologies: The Ideality of Form in/and Code Storage—or—Can Graphesis Challenge Mathesis”). As such, the indexical reader produces signs of a different order, provoking the need for a longer discussion of indexicality in data visualizations and digital media.

The duality of an indexical reader recalls Michel de Certeau’s writing on the qualities of maps versus itineraries which he correspondingly describes as seeing versus going (Certeau 119). De Certeau asserts that it wasn’t always a simple binary of two autonomous forms. He finds a time when maps were entwined with tales of journeys and places. In his discussion of “drawings that outline not a route but the log of a journey,” we can see the self-generating actions of an indexical reader, tapping into an important distinction between its visual displays and those of data visualizations, which, like de Certeau’s maps, “erase itineraries and narratives of their own production” (Certeau 121). An indexical reader retains such traces, and one can imagine how the gathering of texts according to different logics might lead to new indexical reader forms.

Also relevant is Jerome McGann’s call for a digital spatial textuality that is autopoietic, meaning a self-generating system. An indexical structure is an attempt to allow for reading “texts in n-dimensions.” In its simplest terms, this means a text with an infinite number of interpretative perspectives in a field of relations from a clearly identified position inside of the field itself (McGann). While an indexical reader is a highly simplified version of ideas informed by quantum physics, it brings perspective and position to a multitudinous reading experience, implicating yet another dimension of Peirce’s index, the deictic.

Exemplars can help to flesh out a design concept’s core properties and situate it amongst other design instances. Looking for exemplars for the indexical reader — a design concept derived from the conceptual demands of a humanities-based tool and the affordances of a 3-D virtual environment — is challenging, but not impossible. There are projects that share the same basic data structure and document chaining of the Commons Reader View, if not sharing its indexicality. For example, Inke’s Paper Drill is a software prototype designed to enable a user to explore scholarly articles through a similar form of citation chaining (Ruecker et al.). As with the Commons Reader View, a scholar begins with a “seed” article and follows articles that it cites, then articles that they cite, and so on. The interface no longer appears to be online so I rely here on the software’s description in a paper by its creators. Paper Drill would generate an abstract graphical image of the concentric circles of reference around a seed article – a symbolic, rather than indexical, representation. The focus appears to have been on building a tool that would allow a researcher to quickly assess the utility of the chain of references that would be identified, which could frequently generate an overwhelming number of connections, an issue the Commons Reader software would need to address if it were actually created.

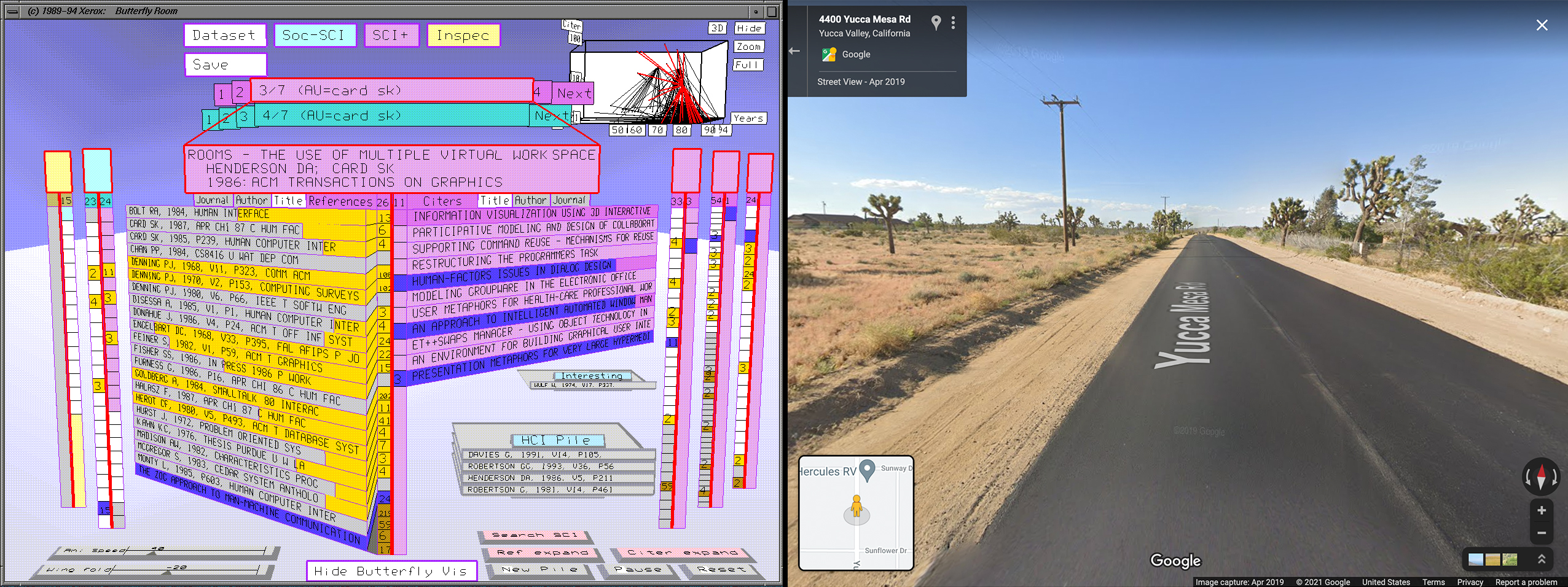

Butterfly, a much earlier prototype developed at Xerox PARC (Figure 16, left), introduces a novel 3-D “visualizer” that shares structural features with the Commons Reader View (Mackinlay et al.). The software is designed for information retrieval in information intensive work, circa 1995. It is published as a demonstration project for an approach dubbed “’Organic User Interfaces for Information Access,’ in which a virtual landscape grows under user control as information is accessed automatically” (Mackinlay et al. 67). While the Butterfly visualizer is not an indexical structure — its forms are abstract geometrical representations — it nonetheless bears an uncanny resemblance to the spindles, with citations that create “wings” leading forward to the right and backward to the left.

In a non-digital example, the layout that is built into the structure of the California Job Case instantiates its intellectual organization. The logic is that of an alphabetic writing system with standardized rules for spelling, grammar, and syntax in which patterns of use are consistent over time. This is then mapped to the movement of a human body. The case can be experienced as an interface for the task of composing lines of text while also being viewed as a measure of the mechanics of an alphabetic system. This dual meaning can be accessed in part due to its size in relation to the human body — its whole can be grasped in plan view, a key feature of an indexical reader.

The most ubiquitous example of the dual perspectives of an indexical reader is Google Street View (Figure 16, right). The ability for a user to zoom from the God’s eye view of a satellite to the eye level and human scale of the street offers the closest approximation to the experience of the Commons Reader view. Similarly, many video game interfaces allow users to switch between first- and third-person perspectives and to view them simultaneously. An indexical reader uses similar techniques to provide a user with a sense of place in a space though it does not construct a virtual world per se. Comparing the Commons Reader View with Google Street View raises questions about how an indexical reader differs theoretically and practically from digital environments created through photographic, cartographic, and simulation software.

Each of the exemplars gathered here points to an aspect of the technical qualities that define an indexical reader — citation chaining, algorithmically-generated 3-D forms, intellectual organization manifest in material construction, and lastly, the ability to dramatically shift viewing perspectives. As seen in each example, such designed attributes are not merely aesthetic choices, rather each has ontological and epistemic dimensions teased out through the use of media, literary, and cultural theory.

As an intermediary knowledge claim, the indexical reader design concept thus blends theory and practice in order to make a unique contribution to either or both. The design concept is meant to be generative, to provoke new instantiations and new theoretical interpretations, at the ready for use in constructing information environments in virtual 3-D spaces that use indexicality to materialize the n-dimensionality of humanities reading practices. The articulation, theorization, and situating sketched out here is just that — an initial sketch, a proof-of-concept to demonstrate the potential of a newly identified design concept.

Conclusion

Through these diverse readings of the speculative digital tools of Trina, I have demonstrated how a prototype created as part of a critical reflective practice is constantly oscillating in the theory-practice nexus. Approaching the design of software from a range of orientations enabled me, as a practice-based researcher, to address diverse facets of a complex and distinct design situation. Diegetic and performative prototypes enacted the technosocial dimensions of the story, making me attentive to the push and pull of an assemblage of actors, human and nonhuman, that give shape to our technologies. The reflexive media critique of speculative software pushed me to develop three distinct prototypes that I designed as a comparative study that exposes the worldviews built into our interfaces. Media archeology provided a way to account for writing technologies at the intersection of bodies and language, which informed the physical relationship of each of the women in the story as they negotiated their own identities through the story’s tech, real and imagined, past and future. And finally, Research through Design’s notion of a design concept allowed me to claim a design-specific contribution — the indexical reader — from an otherwise unruly, multitudinous, and multi-dimensional design project. I hope that others will take it from here.

Works Cited

Agid, Shana. “Worldmaking: Working through Theory/Practice in Design.” Design and Culture, vol. 4, no. 1, Mar. 2012, pp. 27–54. Crossref, https://doi.org/10.2752/175470812X13176523285110.

Agre, Philip E. “Toward a Critical Technical Practice: Lessons Learned in Trying to Reform AI.” Social Science, Technical Systems, and Cooperative Work: Beyond the Great Divide, edited by Geoffrey C. Bowker, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1997, pp. 131–58.

Bleecker, Julian. Design Fiction: A Short Essay on Design, Science, Fact and Fiction. Near Future Laboratory, Mar. 2009, http://drbfw5wfjlxon.cloudfront.net/writing/DesignFiction_WebEdition.pdf.

Burdick, Anne. “Meta! Meta! Meta! A Speculative Design Brief for the Digital Humanities.” Visible Language, vol. 49, no. 3, Dec. 2015, pp. 13–33.

---. “Scenes of Writing.” Proceedings of DRS 2018 International Conference: Catalyst, vol. 1, Design Research Society, 2018, pp. 73–82.

“California Job Case.” Wikipedia, 11 Jan. 2019. Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=California_job_case&oldid=877832600.

Cross, Nigel. Designerly Ways of Knowing. Springer, 2006.

Dalsgaard, Peter, and Christian Dindler. “Between Theory and Practice: Bridging Concepts in HCI Research.” Proceedings of the 32nd Annual ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems - CHI ’14, ACM Press, 2014, pp. 1635–44. Crossref, https://doi.org/10.1145/2556288.2557342.

David, Paul A. “Clio and the Economics of QWERTY.” The American Economic Review, vol. 75, no. 2, 1985, pp. 332–37.

Certeau, Michel de. The Practice of Everyday Life. University of California Press, 1984.

Dewey, John. Experience and Education. Free Press, 2015.

Doane, M. A. “Indexicality: Trace and Sign: Introduction.” Differences, vol. 18, no. 1, Jan. 2007, pp. 1–6. DOI.org (Crossref), https://doi.org/10.1215/10407391-2006-020.

Drucker, Johanna. “Digital Ontologies: The Ideality of Form in/and Code Storage—or—Can Graphesis Challenge Mathesis.” Leonardo, vol. 34, no. 2, 2001, pp. 141–45.

---. Graphesis: Visual Forms of Knowledge Production. Harvard University Press, 2014.

---. SpecLab: Digital Aesthetics and Projects in Speculative Computing. University of Chicago Press, 2009.

Dunne, Anthony, and Fiona Raby. Speculative Everything : Design, Fiction, and Social Dreaming. 2013, http://www.books24x7.com/marc.asp?bookid=57537.

Durrant, Abigail C., et al. “Research Through Design: Twenty-First Century Makers and Materialities.” Design Issues, vol. 33, no. 3, July 2017, pp. 3–10. Crossref, https://doi.org/10.1162/DESI_a_00447.

“ELIZA.” Wikipedia, 14 Mar. 2019. Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=ELIZA&oldid=887796938.

Emerson, Lori. Reading Writing Interfaces: From the Digital to the Bookbound. 2014. /z-wcorg/.

Fuller, Matthew. Behind the Blip: Essays on the Culture of Software. Autonomedia, 2003.

Gaver, William. “What Should We Expect from Research Through Design?” Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, ACM, 2012, pp. 937–46. ACM Digital Library, https://doi.org/10.1145/2207676.2208538.

Höök, Kristina, et al. “Framing IxD Knowledge.” Interactions, vol. 22, no. 6, Oct. 2015, pp. 32–36. Crossref, https://doi.org/10.1145/2824892.

Höök, Kristina, and Jonas Löwgren. “Strong Concepts: Intermediate-Level Knowledge in Interaction Design Research.” ACM Transactions on Computer-Human Interaction, vol. 19, no. 3, Oct. 2012, pp. 1–18. Crossref, https://doi.org/10.1145/2362364.2362371.

Ingold, Tim. Making: Anthropology, Archaeology, Art and Architecture. Routledge, 2013.

Kirschenbaum, Matthew G. Track Changes: A Literary History of Word Processing. Belknap Press: An Imprint of Harvard University Press, 2016.

Kittler, Friedrich A. Gramophone, Film, Typewriter. Translated by Geoffrey Winthrop-Young and Michael Wutz, Stanford University Press, 1999.

Mackinlay, Jock D., et al. “An Organic User Interface for Searching Citation Links.” Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems - CHI ’95, ACM Press, 1995, pp. 67–73. Crossref, https://doi.org/10.1145/223904.223913.

McGann, Jerome. A New Republic of Letters: Memory and Scholarship in the Age of Digital Reproduction. Harvard University Press, 2014. /z-wcorg/.

McPherson, Tara. “Theory/Practice: Lessons Learned from Feminist Film Studies.” The Routledge Companion to Media Studies and Digital Humanities, edited by Jentery Sayers, Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2018, pp. 9–17.

Moretti, Franco. Distant Reading. Verso, 2013.

Parikka, Jussi, and Garnet Hertz. “CTheory Interview: Archaeologies of Media Art.” CTheory.Net, 1 Apr. 2010, http://www.ctheory.net/articles.aspx?id=631.

Peirce, Charles S., et al. The Essential Peirce: Selected Philosophical Writings. Indiana University Press, 1992.

Polyani, Michael. The Tacit Dimension. Doubleday and Co., 1967.

Rosner, Daniela. Critical Fabulations: Reworking the Methods and Margins of Design. The MIT Press, 2018.

Ruecker, Stan, et al. “Drilling for Papers in INKE.” Scholarly and Research Communication, vol. 3, no. 1, 2012, p. 5.

Schön, Donald A. The Reflective Practitioner: How Professionals Think In Action. Basic Books, 1983.

Simon, Herbert A. “The Science of Design: Creating the Artificial.” Design Issues, vol. 4, no. 1/2, 1988, p. 67. Crossref, https://doi.org/10.2307/1511391.

Sterling, Bruce. “Made Up Symposium Keynote, January 29, 2011.” Made Up: Design’s Fictions, Art Center Graduate Press, 2017, pp. 18–26.

Stolterman, Erik. “The Nature of Design Practice and Implications for Interaction Design Research.” International Journal of Design, vol. 2, no. 1, 2008, p. 11.

Stolterman, Erik, and Mikael Wiberg. “Concept-Driven Interaction Design Research.” Human–Computer Interaction, vol. 25, no. 2, May 2010, pp. 95–118. Crossref, https://doi.org/10.1080/07370020903586696.

Suchman, Lucy. Human-Machine Reconfigurations: Plans and Situated Actions. 2 edition, Cambridge University Press, 2006.

---. Located Accountabilities in Technology Production. 6 Dec. 2003, http://www.lancaster.ac.uk/fass/resources/sociology-online-papers/papers/suchman-located-accountabilities.pdf.

---. “Working Artefacts: Ethnomethods of the Prototype.” British Journal of Sociology, vol. 53, no. 2, June 2002, pp. 163–79. Crossref, https://doi.org/10.1080/00071310220133287.

Yasuoka, Koichi, and Motoko Yasuoka. “On the Prehistory of QWERTY.” Zinbun, vol. 42, Mar. 2011, pp. 161–74.

Zimmerman, Claire. “Photography into Building in Post-War Architecture: The Smithsons and James Stirling.” Art History, vol. 35, no. 2, Apr. 2012, pp. 270–87. Crossref, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8365.2011.00886.x.