This discussion is adapted from a presentation by Roderick Coover and Scott Rettberg of Toxi•City and other CRchange projects at the Arts Santa Mònica museum in Barcelona on March 3, 2016.Toxi•City was exhibited there as part of the “Paraules Pixelades” exhibition.

This conversation is published as the third in a series of texts centered around the publication of The Metainterface by Søren Pold and Christian Ulrik Andersen. Other essays in the series include: The Metainterface of the Clouds, Always Inside, Always Enfolded into The Metainterface: A Roundtable Discussion. and Room for So Much World: A Conversation with Shelley Jackson.

Roderick Coover: One of the aspects of our work which is probably apparent is that there's a blending of fictional and non-fictional elements because a lot of our work builds narratively on top of the gathering of non-fiction material. So in my process I go out and I shoot along sets of ideas, systems of images that I gather, collecting buckets of related material and developing a kind of process of looking at conditions of change, particularly in recent times looking at a lot of sites where one might observe the impact of climate change.

In Toxi•City the process began as one of visual research. I was out kayaking on the Delaware River in its tidal zone, a long stretch of river that passes many of the large cities in the American seaboard. The river is home to many of America's largest oil refineries, it was once home to the American steel industry, and shipbuilding industries and the central port for coal and many of the other dirty fossil fuels of the past. At the center of the Delaware the largest city is Philadelphia, which was in the seventeenth and eighteenth century the main economic hub for the US, only to be surpassed by New York quite late in the 19th century. The landscape of the Delaware River estuary is scarred by centuries of early industrial development. Along with Philadelphia it includes a number of cities that are in rather poor state, like Camden, New Jersey, Wilmington, Delaware, and Trenton, New Jersey.

My initial voyage was one of boating along these sites, recording an industrial landscape and I began to speculate what would happen to these landscapes as rising seas from climate change would wash over a landscape of brownfields, of environmental cleanup zones, of active chemical repositories, and begin to mix all of this chemical waste into the land, washing over the cities, not just with salty corrosive seawater but with this toxic waste mix. So I began to explore these landscapes and photograph them, recording what I could see within a potential tidal zone of future floods.

This is something we can see in contemporary news, the story since we started filming has changed, even in the last year or two. The impact of climate change is becoming powerfully obvious. Just recently, for example, this area saw snowstorms coupled with high tides that resulted in whole towns and villages getting flooded. In one particular storm, Atlantic City was under eight feet of water. Flooding has become a fact of life and will increasingly become so.

We started talking about this situation specifically in the Delaware River estuary. I live in this area and Scott used to live in this region as well. We began by asking how people who live in the area have adapted and might adapt as terrible catastrophes related to sea-rise occur, and we followed outcomes of Hurricane Irene, Hurricane Katrina and the many more minor storms that impacted people's lives. While some leave, others die, most just make adjustments in their lives in landscapes that are imagined in new ways. Life goes on but life choices, feelings about places and human relations may all be altered.

I started going out and photographing landscape of the Delaware River estuary from kayak first to collective documentary material and then to gather the substance of what would become a narrative film. It was a process looking for documentary evidence for a changing future imaginary: the worlds we imagine we might inhabit in the years ahead. Scott and I then began to think about the kinds of characters we'd like to follow, and the differing conditions they might face. Given the infinite permutations involved in looking forward, the combinatory structure seemed to offer a perfect structure. An array of images constructs one vision of the future, which is then set against another, and another, and another....

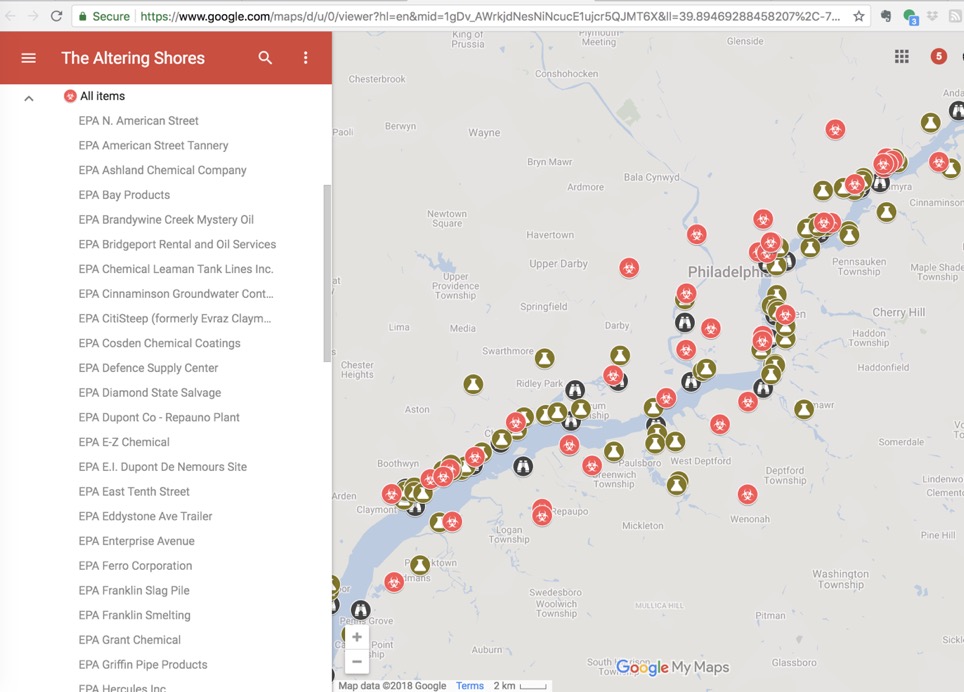

Along with gathering images and sounds, mapping was also an important part of this initial process. I used historic maps to locate former industrial sites that might be disturbed with new floods. This landscape, which was so transformed by the 19th Century industrial revolution, is full of hidden repositories of toxic soils that have since been built upon or left fallow. This hidden landscape is complemented by a contemporary petro-chemical industrial landscape of refineries and chemical plants, while other maps like those of human water use, agriculture and bird migration show how interconnected our lives are with both industrial and natural conditions. The research resulted in the development of The Chemical Map, a kind of online resource identifying over 200 sites within flood zones of potential toxicity, sites that would impact where people live, drinking water supplies and so forth. The map provided additional structure for the gathering of images and a means of setting an objective set of data against my own, personal observations.

Thus, the Chemical Map also grew into a kind of a nonfiction record in the form of an interactive log of exploration, and it's that log that I passed on to Scott. He also started doing additional research on deaths that occurred during Hurricane Sandy and on the potential impact and what life would look like in a near future if events like Hurricane Sandy and this kind of regular flooding we see now became so frequent that it would force people to change where they live or their habits of life.

It's out of this kind of interactive writing and picturing a landscape in a nonfiction form that we move into narrative and we carry that research into a fiction form and that's where Scott and I then began working back and forth, to develop characters and develop an approach to a feature-length film with a combinatory structure. I think this is a pretty rare, unusual form, a full film that refreshes itself about once an hour and recreates itself anew. If you watch the film several times, each time you'll see a different film.

Scott Rettberg: We started working on this project right before Hurricane Sandy hit the East Coast of the USA. When the storm came, I was in Edinburgh, and one morning I picked the newspaper outside my hotel room door and I saw this picture of President Obama standing on this devastated shoreline comforting this woman who had just lost her business in the storm, and I looked at these pictures and I thought "Well that place looks remarkably familiar."

It turned out that Obama was standing about two blocks from the house where I used to live, in Brigantine, New Jersey, during the years before I moved to Norway. And I looked online at Flickr photos and these local New Jersey newspapers, and I found, for example, pictures of my old neighborhood pub, the Rod n' Reel, and it was just completely washed out, inundated, destroyed. The houses on the street where I used to live, the whole north end of the island, just completely wiped out. This is just to say that I think both for Rod and me, as we were working on this project, the situations we were writing about, making a film about, were not completely abstract. The places affected were places that we knew, the people affected were people we saw walking down the streets in neighborhoods we had lived in.

And the contemporary situation of climate change is not abstract. It is a present thing. You are certainly seeing this all the time now, for example in the the flooding in Philadelphia that Rod referenced. Even though we could describe this film as a speculative narrative, it is a very near-term type of speculation, more addressing the imminent horizon than the distant future. And I think that one of the functions of art about climate change is looking at that imminent horizon, both in an analytical kind of way, but also in an empathic kind of way. And maybe one of the powers of media art is to create a different kind of affect, and a different kind of identification, so that we have a better sense of the impact of these problems in human terms.

There are two kinds of narrative here, two layers: one which is absolutely non-fictional. These layers are structured in a way both algorithmically and rhythmically. In between the character-driven narrative segments you hear this kind of what we call a chorus, made up of death stories. I adopted these stories mainly, and pretty directly, from obituaries. This is a very sort of odd genre that we see in the papers when people die in a major disaster. They are both about the disaster itself, and they focus in some sense on how the people died, but they also try to do the work of marking the life and the passing of this particular person, this particular spark of human life that has been extinguished in the event.

A number of our films have tried to engage in some way with how we, as humans, as individuals, as a society, process catastrophic events and deteriorating environmental conditions. And I think that we often rush past them, maybe to avoid dwelling on the trauma. I think we often sort of hear whatever, that 100 people died in New Jersey, or 300 people died during the storm, and we absorb that as a statistic and we move very quickly past it. So by including those death stories, we're trying to keep them as a sort of persistent reminder, maybe to sort of humanize what is happening as a result of climate change, through the inclusion of that layer.

The other layer of the story is a fragmented speculative narrative. Just to say a few words about some of the decisions about the characters: we wanted to represent a number of different perspectives, a number of different types of voices. The six characters sort of represent different age groups, different socioeconomic groups, as well as different types of reactions to the events. Some of this was again based loosely on the non-fiction research that Rod and his students did. The voice of the fisherman character, for example, I adapted the style of that voice, and some elements of his story, from interviews that Rod's students did with longshoremen in Philadelphia. And the voice of the FEMA worker, in a way he serves an expository role, as a way to bring in that factual information about all of these toxic waste sites on the chemical map, this incredible concentration of hazardous material, all of this potential catastrophe lying in wait two or three feet beneath the topsoil. But we also wanted to not simply represent these characters as victims. Sure, they're victims, we're all both victims and perpetrators of climate change, but we know that we will see different kinds of constructive and destructive reactions to these types of events. So you have voices like the pig farmer, who is constructive in his own way, but is also the voice of these really ignorant perspectives on climate change that are still very much part of the contemporary discourse around it.

We've used combinatory structures in several of our projects now, and I think we've explored the poetics of combinatory film in a different way each time. In Three Rails Live, for example, the combination of images and texts is different every time, so in that sense we were exploring how these different juxtapositions work with a sense of closure, or how we as human interpreters create new associations between image and text, regardless of whether or not those associations were intended by the author or filmmaker.

The combinatory structure in Toxi•City was a bit different than that of Three Rails Live—in this case the images and the texts are yoked together but I think there is a poetic reason for using the combinatorial structure. As I said, there are a few dozen of these death stories in the pool. We're trying to take a kind of a panoramic approach to what happens in these sorts of events so the fact that you can watch the film over and over again and each time you're hearing about the passing of different people is, I think, a point that we're trying to emphasize: that there's a singularity to each trauma that climate change produces, it is a human trauma that is experienced individually, as well as a planetary trauma. Each time you watch the film, you're going to hear different death stories, experience these singular traumas, each of which occurred to a different human being who actually lived this moment and actually died (Watch video: 17.mp4).

This work was designed to have more of a narrative flow than some of our other combinatory work in that there are actually clearly defined beginnings, middles, and endings but the mix of them and the order that they are presented in is always changing. And you never hear the whole story on any given run. There is the sense, I think, that these types of events happen everywhere at the same time, and that it is never possible to know them, or to understand them, completely. Nevertheless, to progress in any way, we need to try, we need come to grips with this kind of scattered understanding and not be paralyzed by it.

Roderick Coover: We have discussed this narrative structure as being like the visual metaphor of the waves you see throughout the film. Each time the film runs, there's another array of stories to be told and another set of deaths that happened, but also new potential. With each refresh you've got another set of experiences, another wave of stories, but also fresh sense of possibility for these characters who need somehow to live with hope in facing these situations. I think this is a very important part of talking about catastrophes or risks and dangers. We need have some kind of positive sense, some consideration, of how we can manage to go on in spite of these conditions.

REFERENCES

Coover, Roderick, Nick Montfort, and Scott Rettberg. Thee Rails Live. 2013. http://crchange.net/crchange/projects/ThreeRailsLive/. CR Change Production.

Coover, Roderick, and Scott Rettberg.Toxi•City: A Climate Change Narrative. 2014, 2017. http://crchange.net/toxicity. CRChange Production.