Writing as a life form: A Review of Richard Zenith’s Pessoa: A Biography (2021)

For Fernando Pessoa, as for the roughly 600 texts that make up his Book of Disquiet, and the estimated 136 heteronyms that Pessoa inhabits in his own writing, there "is life, and there is writing, and they must remain immiscible." Richard Zenith's attentive biography of Pessoa succeeds, in the words of Portuguese literary scholar Manuel Portela, in "forming a homogeneous mixture" when all of the names and textual experiences are brought together in a single, biographical narrative.

I’m nothing. I’ll always be nothing. I can’t want to be something. But I have in me all the dreams of the world. -Álvaro de Campos, from “Tobacco Shop” (1928), All translations of Pessoa by Richard Zenith.

To create, I’ve destroyed myself. I’ve so externalized myself on the inside that I don’t exist there except externally. I’m the naked stage where various actors act out various plays. -Vicente Guedes, from the Book of Disquiet (text 299, c. 1918).

I’ve made myself into the character of a book, a life one reads. Whatever I feel is felt (against my will) so that I can write that I felt it. -Bernardo Soares, from the Book of Disquiet (text 193, September 2, 1931).

The first epigraph is the opening stanza from “Tabacaria” [“Tobacco Shop”], a poem authored by Álvaro de Campos, one of Pessoa’s heteronyms. Written in January 1928, it was first published in 1933 in Presença [Presence], the major literary magazine of the second generation of Portuguese modernist writers.1 Those lines set the tone for the entire poem, a disenchanted reflection about the inevitable failure of the self’s desire to be, in its useless quest to construct and inhabit some or other form of being, in its inability to reconcile inner fantasies and the social and material realities of the world, in its awareness of the utter uselessness of any ambition, including the ironic self-acknowledged act of writing the poetry that is coming into existence in this very poem: “And I’ll write down this story to prove I’m sublime.” Nothing seems to be worth the effort.

The stunning power of “Tabacaria” lies in its rhythmic and rhetorical ebbing and flowing of the speaker’s voice, alternating between listing his failures and interrupting his interior monologue with observations about the scenes he witnesses at the Tobacco Shop from his first-floor window. The bittersweet irony of the contrast—encapsulated in the parenthetical remarks throughout the text—suggests that the speaking self’s feeling of inadequacy and frustration is, at the same time, an existential engagement with the inescapable evidence of the reality of the world as perception, sensation, and affection. The poem becomes a paradoxical embodiment of the intensity of desire of the self as a potentiality for being whose fulfilment lies in this paralyzing awareness of the impossibility of fulfilment. As a sentient, self-conscious organism, the speaker’s despair stems from the endless plasticity of its imagination.

The second and third epigraphs come from the Book of Disquiet, an unfinished and fragmentary book made up of c. 600 texts, first composed by Vicente Guedes (1913-1920) and later resumed by the “semi-heteronym” Bernardo Soares (1928-1934).2 The self is presented as a hollow being who can take many shapes. Its person does not exist except as a character, an externalized interiority. This dramatic process of depersonalization—analytically described in “The Art of Effective Dreaming for Metaphysical Minds”3—led him to multiply his identity through imaginary writers. For some of them, Pessoa developed distinct biographies, psychologies, worldviews, and ways of being that gained expression in assigned bodies of writing and book projects. As if this were the first key for entering Pessoa’s literary multiverse, Zenith’s biography begins with a brief presentation of 47 dramatis personae, i.e., all the fictional authors created by Pessoa that are mentioned in this biography (pp. vii-xiv). One of them is “Fernando Pessoa”, a persona who “was just as much a fingidor (feigner, forger, pretender) as the heteronyms” (p. xii). In some way, all identities and personalities—including the one attached to his name—have to be faked, i.e., they have to be performed again and again on the stage of life.

Both epigraphs seem to imply that there is no essential distinction between being a self and being a character, and thus no “inside person” but only shifting and changing impersonations. It is as if the living self were a byproduct of the writing self, designed as a “naked stage” for the performative emergence of characters. Being nothing but a character among characters, the self can only exist through vicarious masks, each face another mask that has to be performed into existence through writing acts. There is no feeling that is not pre-written, i.e., felt for the sake of being written. Referring to the Book of Disquiet, Vicente Guedes writes “This book is the autobiography of a man who never existed” or, in a variant reading, “This book is the biography of a man who never lived” (c. 1917, Appendix 2 in Zenith’s edition). The Book of Disquiet’s program for writing the self out of existence and Zenith’s attempt at writing Pessoa’s self into existence offer contrapuntal directions for thinking about the genre of biography as a narrative account of the life of the individual.

Zenith’s biography locates specific moments and contexts for the appearance and the output of each of those characters in various periods of Pessoa’s life, making readers realize how “heteronyms” (before they became fully developed fictional authors) evolved from a large constellation of named writers that were experimented with since his high-school days. In homemade manuscript newspapers—produced in Durban and in Lisbon, between 1900 and 1905, in his adolescence –, for instance, there were already several imaginary authors mixing fictional and real news, jokes and riddles, short fictions and poems, often imitations and parodies of the periodical press and other sources mined for words, characters and ideas by an avid reader. Some of the earliest experiments with fictional writers were influenced by his collaboration with Henrique Rosa (his stepfather’s older brother), who became an intellectual mentor. Major fictional authors of the 1910s and 1920s—those who authored a significant literary output—include Alberto Caeiro, Álvaro de Campos, Ricardo Reis, Vicente Guedes, Bernardo Soares, António Mora, and Baron of Teive. They were preceded by many others, such as Dr. Faustino Antunes, Eduardo Lança, Dr. Gaudêncio Nabos, Karl P. Effield, W.W. Austin, David Merrick, Lucas Merrick, William Jinks, Horace James Faber, Charles Robert Anon, Jean Seul de Méluret or Alexander Search, several of whom wrote in English, others in Portuguese, a few in French.

The number of fictional authors created by Pessoa has been set by Jerónimo Pizarro (2012) at 136, but only the triad of Caeiro, Campos, and Reis seem to have been considered by Pessoa as “heteronyms,” while Soares—the assistant book-keeper—was described as a “semi-heteronym.” His orthonym (Fernando Pessoa) was also used to sign specific works, initially as one more fictionalized subject among others. From the late 1920s onwards, he projected the future publication of his heteronymic works assigned to their respective fictional authors but subsumed under his own name.4 In December 1928, he published a “Bibliographic Summary” in Presença in which he divided his ongoing works into orthonymous and heteronymous, defining as heteronymous those works signed with other names and written “outside his own person.” Pessoa explained his theory of depersonalization and provided a fictional account about the emergence of his heteronyms in a much-quoted letter to a friend dated January 13, 1935.5

In this account Pessoa describes how—on March 8, 1914, his so-called “Triumphal Day”—he wrote more than thirty poems of The Keeper of Sheep, followed by the appearance of its author, Alberto Caeiro. This was immediately followed by the emergence of the neoclassical poet, Ricardo Reis, by the writing of the six-poem series “Chuva Oblíqua” [“Slanting Rain”] under his own name, and by “Triumphal Ode”, assigned to the futurist Álvaro de Campos.6 Despite the fact that the textual evidence tells a very different compositional story—those heteronyms having been invented and those poems having been written over the course of several months in 1914 –, the literary significance of the appearance of those voices and styles, particularly of Alberto Caeiro, who was described as the master of the other three, cannot be underestimated. Zenith stresses how the emergence of Caeiro—who wrote lines such as “Yes, this is what my senses learned on their own: / Things have no meaning: they have existence, / Things are the only hidden meaning of things”—was a complete mystery for Pessoa himself:

In March 1914 Alberto Caeiro, uttering verses as clear and natural as water flowing down a slope, was nothing else than a revelation, one that Pessoa could never fully fathom. And so the story of his Triumphal Day was not so much a fabrication as it was a metaphor. (Chapter 30, p. 381)

The biographies and astrological charts created by Pessoa for his major heteronyms contain typical models of the lives of writers in the way they connect date and place of birth, education and professional life to works and writing styles. Social and literary theory converge in establishing associations between authors and environments. Caeiro (b. Lisbon, April 16, 1889 - d. 1915), pantheist and sensationist poet, had little formal education and lived in a white house in the country. Álvaro de Campos (b. Tavira, October 15, 1890), futurist and provocative poetry and prose writer, studied engineering in Scotland, travelled to the Far East, and worked as naval engineer in northern England before settling in Lisbon. Ricardo Reis (b. Porto, September 19, 1887), classicist and neopagan poet, studied medicine but became a high-school Latin teacher, and immigrated to Brazil in 1919. Those three accounts of fictional writers fulfil our expectations of finding an explanatory model that links features of each life to features of each work. Capturing the singularity of the individual in relation to the singularity of the work is our basic model for writing a writer’s life.

Within that basic model, the telling of the lives of writers admits a number of variations. Three frequent patterns for narrating lives in relation to writing could be abstracted as writing before living, writing while living, writing after living. Schematic distinctions as they are, those conjunctions encapsulate the ways in which biographers and writers themselves place the production of their work in relation to the production of their lives. Thus biographical (and autobiographical) accounts often reproduce these forms of intelligibility of the temporalities of writing and living. Writers who have produced intensely in their early years and then followed other pursuits, such as Arthur Rimbaud (1854-1891), would fit the first case. Writers who turn their ongoing daily lives into raw material for their work, such as James Joyce (1882-1941), belong perhaps to the second.7 Those who seem to retreat from the world in order to compose works based on their past life, such as Marcel Proust (1871-1922), would enter the third group. Each of those patterns assumes a model of what living is for humans as biological and social beings, seemingly ignoring the practice of writing as its own life form. There is life, and there is writing, and they must remain immiscible: one has to come before or after the other, or they can interrupt each other in parallel streams but without ever mixing up. Writing is not living. Or is it?

This heuristic distinction between writing and living lies at the heart of the process of writing the biography of a writer. Biographers take the trouble of painstakingly documenting the temporality of life events and writing events in order to establish some kind of historical narrative that illuminates the development and evolution of the self of the writer within a network of relations—how s/he felt, thought, acted at significant moments, how those moments relate to their writings, how life follows its own historical course, often refracted in highly indirect ways in the creative process. This explanatory narration is based on an exposition of the social, intellectual and moral formation of the writer’s self, generally according to a “bildungsroman” archetype. Since this documentation of another’s life cannot escape the narrative condition of our epistemological and rhetorical modes for knowing and communicating biographical knowledge, biographies also have to deal with the general constraint of knowledge production. As in other historical genres, there is no bios without graphia. The biocultural pervasiveness of narrative is so strong that this may be true even before life turns into writing: it is not only that biographers cannot tell life without some kind of narrative model, perhaps biographees cannot live life without some kind of narrative model either.

On the one hand, we have a mental and cultural model of the lives of individuals that combines their biological existence in a restricted sense (birth, body form, death, habitat, reproduction, lifespan, etc.) with their social existence in a broad sense (family, education, love life, working life, politics, travels, etc.). We also have documentary and narrative methods for organizing those elements (chronology, events, focalizations, topics, relation of references in written or published works to lived events, transcription of documents, reproduction of photographs, etc.). In their attempt to fill in the name of the author with the density and concreteness of lived experience—showing the author as a living organism in a heterogeneous ecosystem rather than a discursive function in a selected archive of works –, biographers open up their lives and works to forms of historical intelligibility. Through the writing of the life of living, writing can no longer be separated from living. Writing the life of the writer is to experience the porosity of living and writing, the semi-autonomy and discontinuity of the literary work or, rather, its mediating role in the homo scriptor’s semiotic exchanges with their environment. Creativity is an unexplainable scandal, an unpredictable singularity, an uncontrollable anomaly, but also a social and historical process through which writers mediate their being in the world.

On the other hand, for symbolic creatures lives can never be entirely lived without narration. We live by embodying prospective accounts of our own existence. We force ourselves to live narratively. There are a number of available narratives that we have to grow into, either by choice or imposition or, most frequently, as a negotiation of both. Any alternative storyline is another narrative framework. Culture scripts our lived life stories as a number of available forms of being in the world. We learn to script our own actions in teleological terms. Telling our lives is a tentative account that in one way or another links a post factum to an ante factum narrative. Selves seem to be emergent properties of this social narrative machine. The autobiographical nature of the self—the emergence of consciousness as a neurological effect of memory that extends in time our awareness of ourselves as modified by the environment—suggests that our life is also lived as a story telling itself. If this is the case, then graphia is already in bios, and not only in biographia. We live grammatologically. Writing a life is not a precondition for a life to write itself as a form of narrative. A biography can then be imagined as a second degree form of writing life: writing a life whose plight is to write itself through its living. From the matches and mismatches between the biographer’s and the subject’s storylines new plots may begin to emerge.

Yet, we unconsciously know that life also has to be lived without narrative, without discernible connections between actions, feelings, motives. An unstoppable and unrewindable flow of events and states, micro-movements of an organism that must maintain its body homeostasis in a given physical and chemical environment. A continuous flow of sensations that are, to a great extent, independent of any structured perception, any symbolic organization. What is it like to live non-narratively? Is this possible without submitting our minds to the relentless chaos of moment by moment sensations and impressions? Does it necessarily depend on giving away the filter of the self? Not necessarily through the chaotic dissolution of a unified consciousness, but through a surplus of subjectivity, by a relentless multiplication of possibilities. Somehow Pessoa’s “sensationism” is another expression of the hollowness of this formless self: “I, what’s truly I, am a well without walls but with the walls’ viscosity, the centre of everything with nothing around it.” [Book of Disquiet, text 262, December 1, 1931*,* translation by Richard Zenith]. What would this degree of fragmented and disjointed form of being, through writing the self, look like?

If we internalize a narrative model of existence in our living—as something to be experienced as an anticipated narrative that needs to be confirmed and retold retrospectively as time goes by—, this means that biographers also have little choice but to tell our lives based on the narrative models with which we as subjects purport to live them. In the self-imagining of his own literary immortality, Pessoa is trying to write his future biography through the surrogate authorship of the scholars of his life and works. Just by writing about him we follow his script and reinforce his narrative:

Should someone point out that the pleasure of enduring is nil after one ceases to exist, I would first of all respond that I’m not sure if it is, because I don’t know the truth about human survival. Secondly, the pleasure of future fame is a present pleasure—the fame is what’s future. And it’s the pleasure of feeling proud, equal to no pleasure that material wealth can bring. It may be illusory, but it is in any case far greater than the pleasure of enjoying only what’s here. The American millionaire can’t believe that posterity will appreciate his poems, given that he didn’t write any. The sales representative can’t imagine that the future will admire his pictures, since he never painted any.

I, however, who in this transitory life am nothing, can enjoy the thought of the future reading this very page, since I do actually write it; I can take pride—like a father in his son—in the fame I will have, since at least I have something that could bring me fame. And as I think this, rising from the table, my invisible and inwardly majestic stature rises above Detroit, Michigan, and over all the commercial district of Lisbon. (Book of Disquiet, Text 145, February 2, 1931).

Life is transmuted into literary creations whose afterlife depends on future readings. Pessoa’s life narrative is to write himself into the future, counting on the collaboration of his readers to biograph his written life. Our second-degree posthumous narrative, however, always contains several possible biographical stories. Biographers have to negotiate their narratives with all those interpellations and injunctions left behind in the archive. The strong narrativity of Pessoa: A Biography shows how Zenith—even in his scrupulous attention to the factual and textual record—knows that it is never possible to completely disentangle “bios” and “graphia” (in Pessoa’s writing of his “un-living” life and in Zenith’s own writing of Pessoa’s living and writing). This double scripting of life is part of the biographical pact with readers who mostly want stories, all the stories—the writer’s, the biographer’s, their own. Reading about lives is imagining how lives can be lived as stories, what possibilities are out there, and how they can play out as lived narrated lives.

Zenith’s biographical method joyfully embraces narrative and narrativity as the major instruments for the intelligibility and readability of life as written text. The facts that make up the life of a writer must be retrospectively inferred from the textual corpus of the biographee and from a corpus of material witnesses and other testimonies from third parties. In turn, these have to be connected according to interpretative frameworks and patterns that establish causality, motivation, sequence, simultaneity, posteriority, etc. The role of the biographer is to make life writable according to what can be known and according to certain literary conventions and expectations of how we can tell what can be known. The epistemological and the rhetorical cannot be pulled apart. Telling is already its own form of knowing. From this encounter between a model for individual life and a model for narrating life, a writer’s life becomes writable and readable.

While the first model assumes that life is told chronologically as a chained succession of events that tell us how an individual was formed, and what events make his day-to-day living narratable as a meaningful sequence of actions, the second model assumes that narrative unity must also, in some way, be subsumed in the individual’s writing life, that is, in the connections between their “writing life” and their “non-writing life.” Writing the life of an individual who writes thus unfolds in writing the individual’s life and writing the life of that individual’s writing. Even when the biographer is not adopting the model of the so-called literary biography—i.e., an account mostly focused on the history of the writing of the works and based on work-derived inferences—, s/he cannot avoid producing a variation on the model of the literary biography. Literary models of life permeate our collective imagination. Writers are contemporary heroes.

The quality of a writer’s biography is determined by the way in which the narrative of the life of the person and the narrative of the writing mutually illuminate each other. In Pessoa: A biography, this quality is evident from the very beginning. Zenith deeply intertwines the life and writing of Pessoa, offering many precise references that link minutely selected passages to very specific events.8 He is not inferring life from an imaginary and mythologized projection allegorically based on his writing, but rather associating the emergence of topics and texts to the mental flow of Pessoa’s concerns and undertakings at significant moments in his life and vice versa. The link between biographical moments, testimonies in Pessoa’s letters, plans, projects and texts (poems, articles, manifestoes, business plans, horoscopes, etc.) and third witnesses reveals an intense transit between the writing of life and the life of writing. Without denying the relative autonomy of the imagination, Zenith has been able to anchor Pessoa’s texts and reflections in his social and mental life.

This is achieved through his ability to create a vast web of connections and his mastery of narrative voices for biographing Pessoa. There is the third voice of the omniscient narrator who weaves in a wealth of contextual information, but also brief (and relatively frequent) moments of internal focalization that attempt to capture the perspective of Pessoa and other characters, creating clear-cut scenes that appear to the reader as living pictures, simulated tableaux vivants. Characterization is vivid, yet generally closely connected to material witnesses. Three examples illustrate how Zenith turns documents into narrative vignettes. In the first one, at the enticing opening of the book, we have a glimpse of the weather and the agitation in Lisbon’s downtown streets during the feast of St. Anthony as we learn about the birth of Pessoa:

On a pleasantly warm but blustery afternoon, as gusts of wind blew the hats of pedestrians down below, Fernando António Nogueira Pessôa was born to an excited young mother—her first child—in a fourth-floor apartment in the city of Lisbon. It was June 13, 1888, the feast day of St. Anthony of Lisbon, and the feasting was not only religious. There were years when the merrymaking that filled the streets, particularly around Praça da Figueira, got too boisterous, even violent, with fighting and crime spoiling the fun, but not in 1888. The newspaper reported that “the eve of St. Anthony’s passed by calmly, without giving the police much work to do”—just a few scuffles, two or three drunks who had to be locked up for the night, and a pair of petty thieves who were arrested for trying to steal a gold ring. (Chapter 1, p. 3)

This paragraph ends with note number 1, in which we are given the daily newspaper source for the narrator’s knowledge about the weather on that day and the 1888 St. Anthony celebrations (p. 960). In the second example, feelings expressed by Ophelia in her letters to Pessoa and a manuscript poem by Pessoa from their first dating period (1919-1920) provide the basis for this internal focalization of both characters:

What did he write about, Ophelia wondered, and why so much? Intrigued by this man so unlike other men, and whose unusual way with words made her think, and rethink, as well as laugh, she began flirting with him in her first week on the job. Pessoa did not discourage her, he liked the attention, but it also unnerved him. On Saturday, October 18, he wrote two pages for a poem in English whose speaker asks a young infatuated girl why, unless thou wouldst playA prank alike on Fate and me Do thine eyes come my way And thy smiles seek me, who have sought not thee? (Chapter 48, p. 586)

Notes 20 and 21 provide references to Pessoa’s manuscript poem and Ophelia’s letter (p. 994). The third example recreates a conversation at Augusto Ferreira Gomes’s home in August 1934, in which Pessoa’s friend is urging him to finish his book on time for submission to the award created by the National Secretariat of Propaganda:

Mensagem (Message), however, was more than a book that might confer fame and honor on Pessoa, a possibility that fascinated as much as it frightened him; it was a book that could rouse the Portuguese from their slumber and prepare Portugal to be a culturally proud, spiritually aware nation. He had a moral obligation to publish it! So argued Augusto Ferreira Gomes, at whose apartment Pessoa had lately been a regular guest for Sunday lunch. “I’ll take care of the practical details,” Ferreira Gomes promised. All he required from Fernando was a typescript for the printer. (Chapter 70, p. 851)

Thoughts and speeches in this and the following paragraphs are based on a letter by his friend and on research around the publication of Mensagem, but without directly referencing witnesses (note 1, p. 1012). The text is built according to realist conventions for verisimilitude and plausibility in non-fictional discourse, including a specific discursive mode for establishing the reliability of the storytelling narrator. These three examples capture the techniques for linking documents to narrative. With the exception of the occasional footnote (mostly reserved for elucidating terms and historical allusions), the critical apparatus (pp. 960-1020) contains exclusively end-notes that are not too frequent and never break the narrative flow. While the notes serve to authenticate quotes, references and factual information—and thus establish the truth value of text—, the fact that they are scattered within long narrative passages, which are more or less independent of a specific source, contributes to a strong sense of continuity and unity of form. The subtle movement between a self-possessed narrator who is completely confident in the rhythm and structures of his telling, on the one hand, and the non-intrusive referencing of sources demonstrates the biographer’s mastery of narrative unity and narrative flow.

Besides the detached and the empathic narrator of the examples above, two other voices can be recognized: the voice of the historian and the voice of the interpreter. While the first one emerges mostly to provide details of world and national historical events—often taking up the initial, final or intermediate sections of a number of chapters—, the second voice emerges when Zenith advances his own ideas about Pessoa’s love for literature, Pessoa’s engagement with society and politics, Pessoa’s search for spiritual truth (particularly his interest in occultism and esotericism), and Pessoa as a sexual being.

The biographer’s historian voice appears many times, for instance in the account of the Boers War (Chapter 8). The historical narrative generally zooms in on events and transformations of social life that can be documentarily and imaginatively related to Pessoa’s life, namely those that could have been directly witnessed (and for which there are direct or indirect references in his notebooks or works)—such as, in this example, the movement of troops, refugees and prisoners going through Durban. The “historical narrator” is always careful in providing a wider context so that readers can understand the general dynamics of those events:

True to the usual prewar pattern, both sides prepared for armed struggle—the Boers by spending lavishly on weapons for their militias, the British by dispatching ten thousand soldiers from around the empire to Natal—as each avowed these merely “defensive” measures were intended to preserve peace, by discouraging the other side from attacking. (Chapter 8, p. 92)

This is another compositional reason for making Pessoa such an exceptional biography. Whether it is Pessoa’s formal education in Durban (1896-1905), his return to Lisbon at the height of the republican movement (1905-1910), his involvement in the launch of Portuguese modernist magazines in the 1910s and his contributions to several magazines in the 1920s, or his changing feelings in relation to Salazar’s dictatorship in 1935, the historical and local context is richly described, with a sense of proportion that moves effortlessly between the general overview and the close-up, and explicitly connects those historical frescoes with events in his life or with his writings. The historical and social world in which Pessoa lived comes alive through these plentiful descriptions. Zenith’s kaleidoscopic imagination, with attention to the telling detail, and the depth of his descriptions of Pessoa’s work and Portuguese history are often breathtaking.

Descriptions of major historical events—including the Boers War in South Africa, the abolition of the Portuguese monarchy and the fight among different republican parties resulting in the political instability of the 1910s, Portugal’s disastrous participation in the First World War, and the expansion of fascism in Europe in the 1920s and 1930s—are seamlessly integrated into the biographical narrative. They are used to give historical density to Pessoa’s social and political world in a way that shows us how deeply affected by the events of the day he was, and how—despite describing himself through one of his heteronyms as someone “unfit for action”—he was always willing to engage with ongoing events through his writing. This is seen in many unfinished and unpublished texts, but also in several newspaper, magazine articles and booklets, including The Interregnum: Defense and Justification of Military Dictatorship in Portugal (January 1928; later repudiated in 1935).

We find new detailed accounts of well-known events—such as the circumstances surrounding the writing and publication of Mensagem in 1934—, and new interpretations for several dimensions of Pessoa’s intellectual interests, including his effort to gain spiritual knowledge. Building on recent scholarship about the personal library of Fernando Pessoa9 and on the analyses of his readings, a captivating “interpreter’s voice” emerges in many chapters. Realizing that Pessoa’s deep investment in religious knowledge and in esotericism—particularly during the last decade of his life—has received less attention than it deserves, Zenith pays close attention to this spiritual quest. His analysis of Pessoa’s interest in Aleister Crowley and the episode around their correspondence and meeting in Lisbon in 1930, for instance, provide fascinating interpretations of Crowley’s impact on Pessoa’s motives and behavior:

Esoteric religions, on the other hand, claimed to be vehicles for gaining access to hidden truths, a hypothesis Pessoa was far more willing to admit after reading and meeting Aleister Crowley, who impressed upon him two lessons about truth. The first was that all traditions ultimately express the same truths. The second lesson was that the truth, for a spiritually attuned person, is whatever that person says it is. “Say what thou wilt shall be the whole of the Law.” Though he never actually uttered this variation on the core moto of Thelema—“Do what thou wilt shall be the whole of the Law”—Crowley intimated it through his own example. (Chapter 62, p. 767)

A 2021 Pulitzer prize finalist, Richard Zenith’s biography of Fernando Pessoa has been acclaimed as both a research and writing achievement. Thoroughly documented in the minute details of Pessoa’s life, it draws on the immense scholarship about Pessoa’s life and work, including a significant body of work produced by Zenith himself who has been editing, researching and translating Pessoa for more than three decades.10 It is a towering achievement in bringing together what we now know about the life of Portugal’s greatest twentieth-century poet, within a narrative structure that gives historical density to the individual, to his work and to the world he lived in. Pessoa: A Biography is also a brilliant demonstration of Zenith’s narrative skills: in controlling the plot, situating events in place and time, focusing each chapter around one or two major scenes, moving seamlessly from the collective historical background to the individual, placing the individual in an extensive network of affective (family, friends) and wider social relations (fellow writers, publishers, office colleagues, domestic workers, etc.), segmenting the vast mass of information into highly readable units. Like a suspense-paced thriller, the biography is difficult to put down.

One of the formal reasons for this lies in Zenith’s architectural conception of the book as a series of nested bibliographic structures that have symmetrical features or, at least, clearly defined patterns that make it easy to navigate. The book is segmented into reading units of more or less similar extension (76 chapters, a prologue and an epilogue), which are, in turn, internally segmented into 4 to 9 subunits of 2 to 4 pages each. These divisions are further grouped into four major parts that approximately give us childhood and adolescence (“The Born Foreigner”, 1888-1905), youth (“The Poet as Transformer”, 1905-1914), adulthood (“Dreamer and Civilizer”, 1914-1925) and middle age (“Spiritualist and Humanist”, 1925-1935). The equivalence between bibliographical sections and narrative techniques thus approaches the structure of a novel on the education and development of the individual combined with elements of the historical novel. A dense description of family life, education, everyday life and writing production of the character is situated in the wider coordinates of Portuguese, European and global history. The breaking up of chapters into tightly unified sequences shows that, beyond the strictly user experience design logic of dividing a vast amount of information into manageable reading units, there is a narrative rationale to the segmentation.

Towards the end of biography, Zenith transcribes a note in which Pessoa’s numerological imagination divides his life into significant periods. Those four periods closely match the macro-structure created by Zenith for organizing Pessoa’s life. The biographer enters the narrative at this point to express the thrill of this discovery:

He noted, in English:

Every year ending in 5 has been important in my life. 1895—Mother’s second marriage; result—Africa. 1905—Return to Lisbon. 1915—*Orpheu.*1925—Mother’s death. All are beginnings of periods.

A chill ran down my spine when I first laid eyes on this document. (Chapter 73, p. 888)

It is not entirely clear if the biographer’s chill comes from confirming that his master narrative structure for Pessoa’s life matches the author’s own autobiographical perspective, or if it merely refers to the biographer’s general search for local meanings and global patterns. In this case, Pessoa’s note could of course be read as an anticipation of 1935 as another significant date—which turned out to be the year of his death (November 30). The fact that each of the four periods for structuring the biography is framed by an epigraph from the Book of Disquiet indicates that Zenith is reading this particular work as a prismatic refraction of Pessoa’s life. In other words, Pessoa’s narrative about Pessoa (or rather, his semi-heteronym’s “factless autobiography”) remains a powerful constraint in our imagination of his life:

I envy—but I’m not sure that I envy—those for whom a biography could be written, or who could write their own. In these random impressions, and with no desire to be other than random, I indifferently narrate my factless autobiography, my lifeless history. These are my Confessions, and if in them I say nothing, it’s because I have nothing to say. (c. 1929, Book of Disquiet).11

Despite Bernardo Soares’ confessional claims, Pessoa’s life is not factless or eventless. Self-construction only goes so far. Born to a middle-class family in Lisbon, he was raised within an extended family of several aunts and uncles:

The majority of Fernando’s maternal relatives—his great-aunts, the men they married, and their children—were living in Lisbon, and he saw nearly all of them on a regular basis, but his cousins Mário and Maria, who were the only relatives close to him in age, grew up in the Azores. And so his companions in Lisbon were mostly adults, and not just any adults. The men all stood out in their chosen professions, and the women were unusually well-educated homemakers. The boy had to be on his toes to keep up with the conversation. (Chapter 3, p. 45)

His father died from tuberculosis in 1893 when he was five. In 1895 his mother remarried a navy officer, who was the Portuguese consul in Durban, and the family moved to South Africa in 1896. Here he would receive an English education, first, at St. Joseph’s Covent School (1896-1899) and, later, at Durban High School (1899-1905). Zenith’s account of Pessoa’s high-school days provides plenty of information on the curriculum and school practices, but also on what could have been Pessoa’s feelings and his daily routines:

So it was back to full days of classes and evenings dominated by homework. The intensive course of study for Form VI was tailored to prepare students for the next evaluative hurdle: the Intermediate Examination in Arts. Pessoa’s tall stack of study materials included textbooks for subjects such as trigonometry, British history, and French, and no less than four Latin books. In English the examinees would be specifically tested on the seventeenth-century poetry in Palgrave’s Golden Treasury of English Songs and Lyrics. (Chapter 11, p. 149)

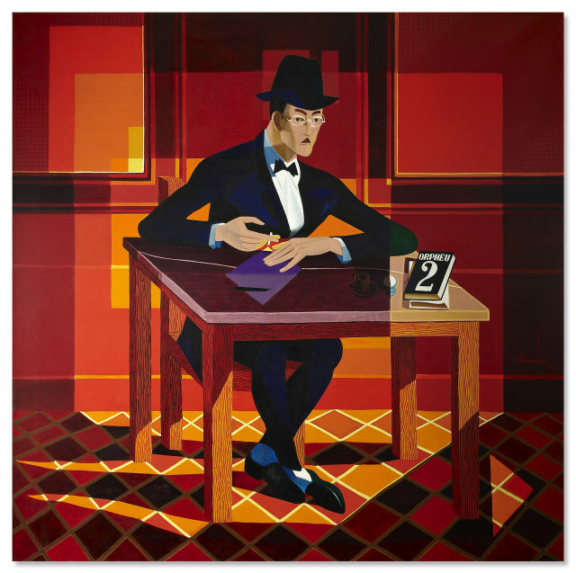

Pessoa returned definitively to Lisbon in 1905 with the prospect of continuing his studies at the School of Arts and Letters. He enrolls in 1905-1906, but fails to sit for exams due to illness; enrolls again in 1906-1907, but drops out before the end of the academic year. Two years later, after acquiring a printing press, he starts Ibis, a printing and publishing business begun at the end of 1909, but the company goes out of business in June 1910. Pessoa had invested and lost all his inheritance money in this project, and accumulated debt. He also started to meet in the cafes of Lisbon with a young generation of writers, including Mário de Sá Carneiro, whom he met in 1912 and who will become his closest friend during the following years (Mário committed suicide in Paris in 1916). Zenith offers a perceptive description of their friendship—expressed in the letters they exchanged about each other’s writings. In 1915, the magazines Orpheu 1 and Orpheu 2, for which Pessoa and Sá-Carneiro were major contributors, launch the modernist movement in Portugal. Except for two self-published chapbooks in English (35 Sonnets and Antinous), published in 1918—republished in 1921 as English Poems I-II and English Poems III (with the addition of “Epithalamiun”)—Pessoa would continue to publish only in magazines through the 1920s and 1930s. His only published book of Portuguese poetry, Mensagem, came out in December 1934.

Throughout most of his adult life, he earned his living as a freelancer, writing commercial letters for several import and export firms based in downtown Lisbon. Bernardo Soares, the second writer of the Book of Disquiet, is an emanation of Pessoa’s office experience. Zenith retells one of the anecdotes about Pessoa’s daily routine at the office:

Pessoa also worked for more than a dozen years—beginning in 1922 or 1923—at Moitinho de Almeida, Lda., an import-export firm at Rua da Prata, 71, conveniently located between his favourite café, Martinho da Arcada, and an outlet of Abel Pereira da Fonseca, a distributor of wines and spirits, which could be consumed by the glass at the counter. Several times in the course of an afternoon, Pessoa would stand up from his typewriter, straighten his jacket and his glasses, put on his hat, and announce to the employees, “I’m going to Abel’s,” where he downed a glass of red wine or brandy. (Chapter 57, p. 694)

Pessoa was also constantly making plans and projects for starting businesses that would give him some financial independence. Most of those ideas never left the paper and the ones that did ended in financial disaster, such as his two attempts to establish a publishing house. Olisipo, in 1921-23, was his second attempt, and through its imprint he managed to publish a handful of impactful works—including books of poetry by two outspoken homosexual authors (António Botto and Raul Leal)—, but it would also prove to be a commercial failure. We learn about several other projects—from cardboard games to tourist guides—for which he never found the necessary investors. Some of those projects could be described as visionary ideas, such as Cosmópolis, conceived in 1915 as a large-scale communication and publishing agency:

To prepare Portugal for its Fifth Empire future, Pessoa drew up grandiose plans for a multifaceted company called Cosmópolis, whose ten separate divisions included Business Services (ideas for company and brand names, outfitting of commercial establishments, letter writing, translations), Literary Services (library research, copy editing, proofreading, typing), Advertising, Legal Services, Publishing, and a Real Estate Agency. (Chapter 39, p. 481-482)

He was a tireless although impractical entrepreneur, his imagination stimulated by his understanding of international trade and the thriving firms for which he worked.

One of the mysteries that seems to have been solved (once and for all?) is that of Fernando Pessoa’s sexual life (“Pessoa copulated with no man or woman”, p. xxviii). The combination of documentary analysis (poems, fragments) with a large set of inferences relating to various episodes at different times in his life indicate, on the one hand, a continuing oscillation between homoerotic and heteroerotic desire, and, on the other, an inner resolution, reiterated on several occasions, to repress his sexual desire as a condition for carrying out his literary project and his intellectual life. Despite the fact that he did not write many texts with sexual allusions, the range of his erotic imagination can be seen in the English masterpieces “Epithalamium” (1913) and “Antinous” (1915), intense expressions, respectively, of heterosexual and homosexual love. Zenith addresses Pessoa’s sexuality and his sexual imagination in many chapters (there are 35 index entries under “sexuality”, p. 1048), ultimately claiming that sexuality was expressed and experienced through words:

Throughout this biography I have avoided defining Pessoa’s sexuality, but based on his spiritual explanations and as demonstrated by his own “practice,” such as it was, it’s possible to affirm that the poet was ultimately not heterosexual, homosexual, pansexual, or asexual; he was monosexual, androgynously so. The heteronyms can be seen as the fruit of his self-fertilization. (Chapter 71, p. 871)

It is a suggestive, if somewhat mystical, interpretation of the heteronyms as the progeny of his androgynous self-procreation, as if fictional selves were an effect of discharges of sexual energy.

To what extent is a biography also a history of the self? How is the life of the self projected in the writing of the self? Throughout the biography, the biographer reads many passages from Pessoa’s poetry and prose—written by heteronyms, semi-heteronyms and para-heteronyms—as documents of the life of the self (of his thoughts and feelings). At the same time, he recognizes the dramatic enactment of subjectivities as hypotheses of being, fictional possibilities of lived and felt life, a machine for multiplying the sensorium. Zenith’s narrative is generally distant from the template of literary biography and its mythification of the writer, and Pessoa: A Biography shows that it is possible to find the person within the author, and consequently to find the “pessoa” [the “person”] in Pessoa. Inferences and assumptions about the self as author are factually authenticated, so to speak, by being placed in relation to other documents and other more or less simultaneous events.

This synchronization of the flow of writing with the flow of life is, to a great extent, one of the major conceptual methods of writers’ biographies. What was the author writing on that date, what relationship exists between texts written more or less on the same date, and how does the event x or y appear mediated in these texts? This exercise is systematic but surgical—testifying to Zenith’s unique breadth of knowledge of Pessoa’s work—, and it is one of the most fascinating aspects of this biography and perhaps the main source of his impressive achievement: the way the biographer interconnects an enormous constellation of texts and facts, and synchronizes countless connections across the domains of bios (family, education, sex, working life, business projects, political life, the self) and graphia (all sorts of written documents, including literary works, photographs)—the archive of multiple documentary witnesses as a network of co-referential documents, i.e., writings from the past that become embedded within the weaving of the biography itself as a form of writing. A biography, as much as an archive, is sustained by a co-referential system.

Can you finally narrate the life of Pessoa? Is there a life to describe? Yes, there cannot not be a life to describe. All writing acts take place within certain material and cultural conditions of production. The question is not the what-to-describe but the how-to-describe what there is. Pessoa’s restless imagination and his abdication of a number of available scripted life forms (“the family man,” “the successful entrepreneur,” “the recognized writer,” etc.) challenge our expectations of how a life should or could be narratively lived. This, in turn, creates the problem of matching lived life to the narrative models for telling lived life. Pessoa’s posthumous worldwide recognition suggest that his “Super-Camões” narrative script for his future reception may have been his alternative life form and his supreme fiction.12 A fiction that we must turn into the master narrative that confirms Pessoa as the ultimate embodiment of literary genius by making us willing participants in his contradictory staging of his own immortality.13 A fiction that counted on us—his future editors, scholars, biographers, readers—in order to make that paradox real and fulfil Pessoa’s search for lost future time. Pessoa’s life cannot be completely disentangled from Pessoa’s posthumous life, as we are already caught within the interpellation of an expanding narrative web about his life writings.

Robert Bréchon (1920-2012), French scholar and translator of Pessoa, published a literary biography in 1996 under the title Étrange étranger [Strange Stranger], inferring Pessoa’s person from Pessoa’s personae, often subsuming the person under the writer.14 He reinforced not only Pessoa’s narrative construction of himself as a heteronymic writer, but also the available templates for narrating the life of the writer as a literary genius and cultural hero. In Bréchon’s literary biography, Pessoa often takes the form of a character derived from his own writing since many factual events seem to be validated only through their textual representation in Pessoa’s works. In Zenith’s documentary approach to biographical narrative, we find an entirely distinct movement, as the writer and the writings are strongly subsumed under the person, and only very specific references in the texts are read biographically. Without ignoring Pessoa’s fictions of himself and of his surrogate selves, Zenith weaves a highly complex, layered and inflected narrative to let us see how Pessoa lives beneath, beyond and through his work.

At the same time, there seems to be no complete satisfactory answer to these questions: Where does the description of life stop? Where is the border between lived life and imagined life? Between sitting at a desk, typing and smoking, and the invented thoughts and feelings of a multitude of selves? Can I really make myself into a character? What happens when I surrender myself to the mental desire to be and feel in many different ways as Pessoa seems to have done? When the process of writing stages itself as a dramatic performance spanning over more than three decades? When I am—and, somehow, we still cannot prevent ourselves from looking at a great artist in this way—divinely touched by the eloquent madness of language? The impossibility of disentangling living from writing and the acknowledgement of Pessoa’s writing practice as a form of living is pointedly captured by the title of the British edition of the biography: Pessoa: An Experimental Life (Penguin, 2021). Here is Zenith’s attempt at offering a synthesis of the life of his subject:

His poems and prose pieces were him, his own person, or the bits and pieces of the person, or Pessoa, who did not exist as such. His sexual life? His spiritual life? They may be found in his writing, and nowhere else but in his writing. There is no secret Pessoa for the biographer to reveal.

Fernando Pessoa was an experimentalist, whose own life was the permanent subject of his research. Each of the heteronyms was an experiment, as was each of the philosophical, political, literary, and religious points of view that he successively adopted and successively abandoned. His relationship with Ophelia Queiroz was an experiment. So was the correspondence he had recently struck up with Magde Anderson. His attempts to be a businessman. His communications with astral spirits. […] All were experiments, most of whose procedures and results he recorded, like a scientist of love, of commerce, of religion, and so on. (Chapter 76, p. 931)

The epilogue (pp. 933-937) is made up of thirteen entries briefly detailing the remaining lives of important dramatis personae (friends and family) after Pessoa’s death. It is typographically symmetrical to the list of fictional authors created by Pessoa that Zenith lists at the beginning as an ante-chamber to the prologue (pp. vii-xiv). The epilogue also seems to evoke the practice—on films “based on real-life events”—of telling the viewers about the future destinies of the real persons whose characters we have just learned about in the film. Given the witness- and document-based nature of biography as a historical non-fiction genre, Pessoa’s fictional authors and real persons in his life must remain ontologically distinct. Distinct epistemological rules apply to fictional and non-fictional entities. However, they have to share their common narrative condition as verbal presentations: accounts of characters are modelled on real lives and on models of characters; accounts of real persons are modelled on real lives and on models of persons. Persons offer models for characters while characters offer models for persons.

Pessoa’s literary work seems to rhetorically challenge the ontological distinction between being a person and being a character, suggesting the possibility of multiplying forms of being by hollowing out one’s self from a particular life script. This awareness of the performative condition of the self—and thus, of the possibility of othering the life of the self—can help us recognize biography as yet another mode of constructing characters. The bibliographic symmetry between fictional authors created by Pessoa and real persons in his life selected by Zenith—placed as if they were bookends sustaining the opening and closing of the biography—suggest the narrative affinity of their written endeavours. A certain level of recursion comes to light: Pessoa as a real person shares the life of Pessoa as a character who shares the life of Pessoa as a real person.

After placing every reference to time, place, persons, events and actions in a coordinated system of documents from multiple archives, and establishing the truth value of many thousands of fact-checked elements, Pessoa’s life still cannot be separated from his writing. Pessoa: A Biography offers an original, thoroughly researched and highly-readable narrative about the formation of Pessoa as an individual and as a writer. We can see the minute particulars of how he was produced by the social forces of family, education, language and culture, but also how he was constantly exploring and expanding the technologies for self-construction. His intellectual and literary quest was an ontological and existential research into the nature of desire, consciousness, self, being, writing. What is possible? Zenith’s remarkable achievement as biographer is to make us realize how Pessoa relentlessly explored this question by turning writing into a life form.

Works Cited

Bréchon, Robert. Étrange étranger: une biographie de Fernando Pessoa. Paris: Christian Bourgois, 1996.

Castro, Mariana Gray de. “Pessoa, Coleridge, homens de Porlock e dias triunfais: sobre génio, inspiração, interrupção e criação poética.” Revista Estranhar Pessoa, 1 (2014): 58-70.

Crespo, Ángel. La vida plural de Fernando Pessoa. Barcelona: Seix Barral, 1988.

Drucker, Johanna*.* Iliazd: A Meta-Biography of a Modernist. Baltimore, MA: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2020.

Ellman, Richard. James Joyce. New York: Oxford University Press, 1982 [1st ed. 1959].

Holmes, Richard. Coleridge: Early Visions, 1772-1804. New York: Pantheon Books, 1999 [1st ed. 1989].

Holmes, Richard. Coleridge: Darker Reflections. New York: HarperCollins, 2005. [1st ed. 1989].

Painter, George D. Marcel Proust: A Biography. Two volumes. New York: Random House, 1989 [1st ed.1959].

Pessoa, Fernando. Heróstrato e a Busca da Imortalidade. Edited by Richard Zenith. Translation by Manuela Rocha. Lisbon: Assírio & Alvim, 2000.

Pessoa, Fernando. Escritos Autobiográficos, Automáticos e de Reflexão Pessoal. Edition and Afterword by Richard Zenith. Translation by Manuela Rocha. Lisbon: Assírio & Alvim, 2003.

Pessoa, Fernando. The Book of Disquiet. Edited and translated by Richard Zenith. London: Penguin, 2015 [1st ed. 2002].

Pessoa, Fernando. Fernando Pessoa & Co.: Selected Poems. Edited and translated by Richard Zenith. New York: Grove Press, 2022 [1st ed. 1998].

Pizarro, Jerónimo. Pessoa existe? Lisboa: Ática, 2012.

Portela, Manuel, and António Rito Silva, eds. LdoD Archive: Collaborative Digital Archive of the Book of Disquiet, Coimbra: Center for Portuguese Literature at the University of Coimbra, 2017-2022. https://ldod.uc.pt/

Robb, Graham. Rimbaud: A Biography. New York: Norton, 2000.

Sepúlveda, Pedro, Ulrike Henny-Krahmer, and Jorge Uribe, eds. Digital Edition of Fernando Pessoa: Projects and Publications. Lisbon/Cologne: IELT-Institute for the Study of Literature and Tradition, New University of Lisbon, and CCeH-Cologne Center for eHumanities, University of Cologne, 2017-2022. http://www.pessoadigital.pt/en/index.html

Simões, João Gaspar. Vida e Obra de Fernando Pessoa. Lisbon: Bertrand, 1971 [1st ed. 1950].

Tabbi, Joseph. Nothing Grew but the Business: On the Life and Work of William Gaddis. Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 2015.

Zenith, Richard. Pessoa: A Biography. New York: Liveright/Norton, 2021.

Footnotes

-

Facsimile reproduction (and transcription) as it appeared in Presença can be read here: http://www.pessoadigital.pt/pt/pub/Campos_Tabacaria (Pedro Sepúlveda, Ulrike Henny-Krahmer and Jorge Uribe (eds.), “Tabacaria,” Digital Edition of Fernando Pessoa: Projects and Publications. Lisbon/Cologne: IELT/CCeH, 2017-2022). A translation by Richard Zenith is included in Fernando Pessoa & Co.: Selected Poems (New York: Grove Press, 2022 [1st ed. 1998]). Also available online at https://www.ronnowpoetry.com/contents/pessoa/TobaccoShop.html ↩

-

A facsimile reproduction and transcription of all the texts from the Book of Disquiet can be read here: https://ldod.uc.pt/ (Manuel Portela and António Rito Silva, eds, LdoD Archive: Collaborative Digital Archive of the Book of Disquiet, Coimbra: Center for Portuguese Literature at the University of Coimbra, 2017-2022.) See also Fernando Pessoa, The Book of Disquiet, edited and translated by Richard Zenith, London: Penguin, 2015 (revised translation [first edition 2002]). ↩

-

Book of Disquiet, c. 1914. https://ldod.uc.pt/fragments/fragment/Fr549/inter/Fr549_WIT_ED_CRIT_Z ↩

-

When he died in 1935, at 47, Pessoa left c. 28,000 unpublished manuscripts (housed at the National Library since the late 1970s), which have provided textual work for several generations of literary editors and scholars. Heteronymic writing in Pessoa has been a persistent subject of research and debate since the posthumous publication of his works started in the 1940s. Editors have held divergent views on whether to assign works to heteronyms or directly to Pessoa. A critical edition of his complete works, published by Imprensa Nacional-Casa da Moeda, is ongoing since 1990 (24 volumes were planned, most have been published, a few remain in preparation). Editors continue to transcribe documents from Pessoa’s Archive, which has now been completely digitized by the National Library. Pessoa Plural: A Journal of Fernando Pessoa Studies, with two issues per year, was established in 2012 in open access. ↩

-

This letter was addressed to his friend Adolfo Casais Monteiro, a fellow poet, critic and translator. A digital facsimile of the typescript letter (BNP Esp. E15/2719) from Pessoa’s Archive at the National Library of Portugal can be seen here: https://purl.pt/13858/1/correspondencias/283.html A transcription of this letter is available at Casa Fernando Pessoa: https://www.casafernandopessoa.pt/pt/fernando-pessoa/textos/heteronimia ↩

-

This mythical account of Pessoa’s “scene of writing” has been analyzed as a parody of the preface to Coleridge’s “Kubla Khan: or A Vision in a Dream” (Castro 2014). ↩

-

In James Joyce (first published in 1959, revised 1982), Richard Ellman famous opening paragraph describes how life and writing become entangled in a feedback loop in Joyce’s compositional process, and how that, in turn, must be mediated in his biographical narrative: “We are still learning to be James Joyce’s contemporaries, to understand our interpreter. This book enters Joyce’s life to reflect his complex, incessant joining of event and composition. The life of an artist, but particularly that of Joyce, differs from the lives of other persons in that its events are becoming artistic sources even as they command his present attention. Instead of allowing each day, pushed back by the next, to lapse into imprecise memory, he shapes again the experiences which have shaped him. He is at once the captive and the liberator. In turn the process of reshaping experience becomes part of his life, another of its recurrent events like rising or sleeping. The biographer must measure in each moment this participation of the artist in two simultaneous processes.” (3). Biographers have to strike a difficult balance between chronicling in (sometimes) excruciating detail the trivial routines of life and selecting significant moments that will provide illuminating connections between living and writing. Those decisions are further situated within a self-conscious awareness about how lives and works are being constructed through particular biographical methods, interpretative frameworks and narrative forms. Different ways of solving biographers’ narrative dilemmas can be seen in these five examples: George D. Painter, Marcel Proust: A Biography (two volumes; first published in 1959, revised 1982); Richard Holmes, Coleridge: Early Visions, and Coleridge: Darker Reflections (1989); Graham Robb, Rimbaud: A Biography (2000); Joseph Tabbi, Nobody Grew but the Business: On the Life and Work of William Gaddis (2015); and Johanna Drucker, Iliazd: A Meta-Biography of a Modernist (2020). ↩

-

The “Chronology of Pessoa’s Life” (pp. 949-958) lists the most significant dates (years, a few months in each year, and also some calendar dates). However, the flow of time within the text often follows Pessoa month by month. See, for instance, Chapters 36-40 (pp. 442-497) dedicated to the year 1915. ↩

-

Housed at Casa Fernando Pessoa in Lisbon, Pessoa’s private library of c. 1300 titles was digitized in 2010. For the past decade, new studies have analyzed his readings and his marginalia looking for evidence of influences and creative appropriations. Catalogue and digital facsimiles of all the books in the library are available here: https://bibliotecaparticular.casafernandopessoa.pt/index/index.htm ↩

-

Zenith’s edition of Livro do Desassossego [Book of Disquiet, 1998], as well as his editions of Heróstrato e a Busca da Imortalidade [Erostratus or The Future of Celebrity, 2003] and of Escritos Automátcos, Autobiográficos e de Reflexão Pessoal [Automatic, Autobiographical and Personal Reflection Writings, 2006] are three instances of editorial work that have contributed to the interpretative framework of the biography. There are more than 50 references to the Book of Disquiet, extending across the four parts of Pessoa: A biography. Pessoa’s astrological charts and automatic writings of 1916-1917 are given significant attention, particularly those mediunic written conversations with spirits that announced his forthcoming sexual encounters. The 2006 volume contains an extended afterword titled “Notes towards a factual biography” (pp. 431-517), which was Zenith’s first rehearsal as Pessoa’s biographer. ↩

-

Text 12 in Zenith’s edition and translation. Facsimile and transcription of the original document is available here: https://ldod.uc.pt/fragments/fragment/Fr177/inter/Fr177_WIT_MS_Fr177a_199 ↩

-

In his first articles of literary criticism, “The New Portuguese Poetry Sociologically Considered” and “The New Portuguese Poetry Psychologically Considered” (published in 1912, in the magazine A Àguia), Pessoa claimed that the new poets were preparing the way for the emergence of a “Super-Camões” (i.e., a poet that would eclipse Luís de Camões). ↩

-

For Pessoa’s texts on immortality and literary fame, see: Heróstrato e a Busca da Imortalidade [Erostratus or The Future of Celebrity], edited by Richard Zenith (Lisbon: Assírio & Alvim, 2000). ↩

-

The first biography of Pessoa, written by João Gaspar Simões (1903-1987), Vida e Obra de Fernando Pessoa (1950; revised edition, 1971), focused on a psychological interpretation of the author. The second major biography was written by Ángel Crespo (1926-1995), La vida plural de Fernando Pessoa (1988). ↩

Cite this review

Portela, Manuel. "Writing as a life form: A Review of Richard Zenith’s Pessoa: A Biography (2021)" Electronic Book Review, 8 January 2023, https://doi.org/10.7273/dc1v-2t26