A personal recitation of Paul Ingendaay's career as a "lifelong" associate editor with the Frankfurter Allgemeine. Ingendaay also shares with us a recollection of the slow, belated but definitive situation of Gaddis's lifework in the German literary canon.

It’s hard to explain why the work of William Gaddis reached Germany so late, with the translated publication of Carpenter’s Gothic, his third novel, in 1988.1In subsequent footnotes I provide the full publication information upon mentioning each German translation of Gaddis’s novels. Carpenter’s Gothic was first published as Die Erlöser, Trans. Klaus Modick and Martin Hielscher. Rowohlt, Reinbek 1988. There had been an abandoned translation attempt of his massive The Recognitions in the sixties, as I will explain more fully below, but nowhere did the German literary market follow the lead of other European countries such as France, Italy, or Spain, where Gaddis was translated decades earlier. Especially surprising, then, was the triumphant arrival on the German scene in 1996 through 1998 with the almost simultaneous publication of translations of his three major novels – The Recognitions, J R, and A Frolic of His Own – in two different German publishing houses, and a subsequent acclaim of reception that may have outdone anything he received elsewhere in his lifetime. The following pages will try to tell this story, combining scholarly information with a more personal approach.

To say that the work of William Gaddis was influential in my life, both in my development as a human being and in my professional career, would be grossly understating the case. For it was sheer enthusiasm that brought me to Gaddis in the first place – I only discovered his novels in 1987 – and it must have been something akin to missionary zeal that made me write my first published essay ever, in 1988, on the work and career of this author, although it cost me a lot of hard work to condense the complexities of Gaddis’s textual strategies into a coherent account.

My essay (“Zauberer ohne Publikum”), back then, was published in the German literary magazine Schreibheft, which had brought out a piece by Bernd Klähn (“Diskurs der Moderne”), on American ‘postmodernist’ literature, including The Recognitions, a year earlier, probably the first time ever that Gaddis’s name was mentioned in any German publication. The same issue carried an excerpt from The Recognitions translated into German, along with excerpts of works by John Hawkes, William H. Gass, John Barth, Gilbert Sorrentino, and others of that generation. In fact, all the early efforts on behalf of Gaddis by German aficionados of what was then called “postmodernist” American literature are inextricably linked to Schreibheft, the pioneering German avantgarde magazine, edited by Norbert Wehr, and still very much alive today.

What I’m going to tell you here started with a student of American Literature looking for a subject for his M.A. thesis in the summer of 1987. Having secured all necessary credits, I had taken time off from Munich University and spent some four months in Mexico, working on a book of fiction and learning Spanish, when, on my return trip, I stumbled in New York’s Shakespeare & Company upon the Viking Penguin reissue of Gaddis’s first three novels.2Full publication information for the Viking Penguin Gaddis editions: The Recognitions [1955]. Viking Penguin, New York 1985. J R [1975]. Viking Penguin, New York 1985. Carpenter’s Gothic [1985]. Viking Penguin, New York 1986. I still recall the sensation of seeing all three of them grouped together up there on the shelf: the blue-backed Recognitions, the red J R, and the yellow Carpenter’s Gothic. Why, I asked myself first puzzled, then dumbfounded and utterly at a loss for a reasonable explanation, had I never even heard this writer mentioned, let alone seen any book of his anywhere, neither in bookstores nor in our well-stacked university library? This was how I first learned about Gaddis’s “elusiveness” or almost clandestine existence on the margins of the literary market. (Ironically, I wasn’t aware that Gaddis himself was in Germany in 1987 giving interviews at just about the time I discovered him in New York.)3See for example the painter Dirk Görtler’s brief memoir of an event on this tour: https://williamgaddis.org/reminisce/remgoertler.shtml

Reading the initial sentences of The Recognitions, I realized then and there that this was a serious, demanding, excitingly interesting author worth critical attention, and dipping into the first few pages of the masterful dialogue of J R showed me in a matter of minutes that Gaddis’s literary register was immense. Again, I wondered. Why on earth had no one I knew taken up and discussed his novels, not even on the corridors of Munich’s Department of American Literature where Thomas Pynchon, Don DeLillo, John Barth, Robert Coover, and a bunch of minor voices of American metafiction were household names? It strained belief and it still does now.

I have never received a fully satisfying answer to these questions. I can only state here that I made an experience common to many Gaddis readers: that literary reputation is a fickle business and can’t be trusted or predicted; that sales figures and the fame game are misleading categories most of the time; and, finally, that the so-called market tends to tell us one story, while literary value and, to borrow Nabokov’s lovely phrase, “aesthetic bliss” are quite another matter and depend entirely on the individual experiencing them. All of this, of course, might seem obvious, and even more so today. But it’s likely to be forgotten when one tries to recreate the initial moments of first encountering a truly powerful, unforgettable literary voice such as Gaddis’s. One wants to understand why one is drawn to a given writer’s style, or tone, or temper. One wants to be ever conscious of one’s aesthetic choices.

Faithful to chronological order, I bought The Recognitions on the spot, with the two succeeding novels to follow in the ensuing months. I brought the thick book home, along with my Mexican mementoes: I read it and studied it, laid out filing cards on library desks, took notes, started using funny symbols and complex color schemes for my annotations, and ploughed my way through Gaddis’s literary universe of myth, religion, and techniques of forgery. Naturally, before the advent of the word processor, recurring phrases and motifs were chased throughout the book in the old style, by leafing through the text again and again, scanning the pages, and scribbling notes in the margins. Somehow, to me, much of it seemed to be about dissecting the book first and putting it back together again in order to fully grasp its material being, like the inner workings of a well-crafted clock.

As a reader, I probably came well-prepared. Only three years earlier, I had had the privilege of attending the first seminar Hans-Walter Gabler, professor of English Literature at Munich University, offered using his recently published, first-ever critical edition of Ulysses. Naturally, in my early encounters with Gaddis, I deeply sympathized with Steven Moore’s approach as embodied in his Reader’s Guide to William Gaddis’s ‘The Recognitions’ to first and foremost lay bare the literary, cultural, and mythological allusions buried deep in the fabric of this remarkable début novel (much as Joyce, thirty-three years earlier, had smuggled his erudition and playfulness into his ground-breaking Ulysses) and then, but only then, discuss everything else.

I had finished my M.A. thesis on J R – for my money, no pun intended, still Gaddis’s supreme novel – and contemplated doing a PhD on the whole body of his work when in 1988 his third novel, Carpenter’s Gothic, came out in German, at Rowohlt. The German title Die Erlöser (“The Saviours”) makes reference to the aura of religious fanaticism pervading the book. I published a review (“Apokalypse…”) in Süddeutsche Zeitung and, half a year later, a more extended piece (“Kunst aus dem Geist”) on Gaddis’s then-entire output in the Frankfurter Allgemeine’s luxuriously designed weekend supplement.

The pieces on Gaddis, though I wasn’t aware of it at the time, were the starting point for my lifelong association with the Frankfurter Allgemeine, leading first to my post as literary editor in 19924Twelve months into the job, I published my PhD under the title Die Romane von William Gaddis. Wissenschaftlicher Verlag Trier, Trier 1993. and, from 1998 through 2013, to being the paper’s cultural correspondent in Spain and subsequently European correspondent based in Berlin, a job I still hold today. It all started with Gaddis; or rather, with my understanding that literary criticism should explore new, bold forms of writing and make them known to readers. On a more personal note, I might add that my life, since then, has always been connected to Gaddis’s work. Somewhere along the line I realized I wouldn’t have become first an editor, then a newspaper correspondent without Gaddis, because the very first book review I ever wanted to write was when Carpenter’s Gothic came out in German – and I, at twenty-eight years of age, had a distinct feeling I just had to preach to the ignorant.5My brother, Marcus Ingendaay, has an even bigger claim to say such a thing. He began his career as a professional literary translator by doing short pieces by Gaddis for Schreibheft and went on to do acclaimed German versions of The Recognitions and (jointly with Klaus Modick) J R, as well as Moore’s Reader’s Guide. In yet another twist of fate, my invitation by Paul Michael Lützeler, then Head of the Department of German Literature at Washington University in St. Louis, to come teach as a visiting professor for a stint in early 2020, just before the outbreak of the pandemic, brought me right to the place where the Gaddis papers are housed: the Special Collections of the Library of Washington University in St. Louis. My thanks go to Joel Minor and the enormously helpful library staff for making me feel welcome in this special place and allowing me a few afternoons with the material Gaddis legacy. Deeper thanks are due to Joel for reconnecting me to the Gaddis universe by including me in all further communication to do with the Autumn 2022 Gaddis conference at Washington University, and the call for papers which urged me on to remember and collect my thoughts on Gaddis for this present occasion.

The reception of Carpenter’s Gothic (translated by Klaus Modick and Martin Hielscher) in the German market in 1988 was unanimously positive. 6Gerhard Kirchner points out Gaddis’s “profound malice” and the reader’s enjoyment of the author’s “grotesque as well as grandiose tragicomedy,” expressing his hope that Gaddis may find a larger audience in Germany than he did in the US. Which he eventually did Some reviewers took the trouble to mention that Gaddis’s third novel was a minor achievement compared to the two towering novels that went before. One of them, especially, the famous critic Fritz J. Raddatz, writing in the weekly Die Zeit, hailed Gaddis’s late arrival as an indicator of a work of genius thus far hidden from the German public (“Schwarzer Spiegel”). In this, however, Raddatz was not entirely honest, for certainly he had been involved in some of the hiding. For instance, he failed to mention in his review that he himself, as editor at Rowohlt in the sixties, had shelved an attempt to have The Recognitions translated into German. In fact, Raddatz’s name was the only one Gaddis recalled when, in our first personal encounter in Long Island in 1989, he and I talked at length about how his work had fared earlier in Germany. There had been rumors, Gaddis told me, of a fire on the publisher’s premises allegedly consuming large chunks of the translated manuscript of The Recognitions, a wild story Gaddis had no way of verifying and appeared not to find entirely credible. There were other rumors of the kind that the job had been given up as too time-consuming, if not outright impossible.

Be that as it may, Gaddis’s tone, to me, suggested a certain disappointment, but then – as he always made abundantly clear in conversation7After my first visit in Long Island at the author’s home in 1988 (then in the Georgica Settlement, Wainscott, with access to the pond included) I saw Gaddis a few more times throughout the following ten years. These visits were rather long, lasting two to four hours, the first time with Gaddis frying fish and serving lunch, at other times over coffee in the living room. In 1995 I visited Joseph Heller, just a few miles away, and went on to see Gaddis who told me about his delight at the prospect of being finally published in Germany. – he was long used to being called “difficult”, “hard to translate”, and, most of all, even harder to sell. He eventually told me in 1995 how happy he was to be finally set for publication in Germany. In this context, I think it deserves mention that, during the time that Germany strangely, inexplicably ignored him through the first three decades of his literary career, there came out translations of one or both of his first big novels in France, Italy, and Spain, to name just a few.

Now that one of his novels was positively received in Germany, the platform was created for a more receptive audience for whatever came next. It would have been hard to predict, however, just how significant a figure Gaddis became with his next German translations. To enter the nineties and talk about how Gaddis fared in the German market is to highlight the curious fact that his three largest novels irrupted on the scene as a bulk within the short span of just two years, making the order of their publication in America, not to mention the author’s artistic development, all but unrecognizable. Thus, translations of J R and A Frolic of His Own came out in fall 1996 (at Zweitausendeins and Rowohlt, respectively8As J R, Trans Marcus Ingendaay and Klaus Modick. Zweitausendeins, Frankfurt am Main, 1996. And as Letzte Instanz, Trans. Nikolaus Stingl. Rowohlt, Reinbek, 1996.), followed in 1998 by The Recognitions and an updated edition of Steven Moore’s Reader’s Guide, again at Zweitausendeins.9As Die Fälschung der Welt, Trans. Marcus Ingendaay. Zweitausendeins, Frankfurt am Main, 1998. And (Moore) as Die Fakten hinter der Fälschung. Trans. Marcus Ingendaay. Zweitausendeins, Frankfurt am Main, 1998.

The gap of more than forty years between the first American publication and the delayed German edition of The Recognitions plays a crucial role in understanding how Gaddis was received over here: as a visionary satirist and a postmodernist master who allowed us to understand, and make sense of, the profound changes over the American decades just passed. Given the atmosphere in German society at large, with financial worries over reunification costs and the first signs of early gamblers at the stock exchange via the internet, the mood seemed to be ripe for reading a truly satirical mind on money, mergers, and the cynicism of business strategies relying on the almost fictitious quality of empires built on paper. In that respect, Gaddis’s J R, for example, may have been perceived in Germany as an even more fitting novel for the nineties than for the seventies, when it was written, at a time when many of the abuses of the stock market lay still in the future.

Still, there were obvious drawbacks. It is difficult to do justice to complex literary texts when one virtually obliterates the traces of their historicity and robs them of the fingerprints of their age; then again, one might argue just the opposite and say that there is much to be gained, too. For one thing, Gaddis finally appeared with a loud bang as the literary giant he had always been to his devoted readers. For another, Germans were able to take in, perhaps even ponder and digest, an entire ecosystem of literary craft and technique all at once. Not surprisingly, then, renowned German reviewers took on the forbidding challenge and went on to explain to their audiences what “reading Gaddis” truly meant. Looking back on Thomas Pynchon and Don DeLillo rather than forward, towards them, the inverted timeline served to discover something like a new continent that had always been there but hitherto shrouded in dense mists. One hardly overstates the case when pointing out that William Gaddis was the most showcased, most enthusiastically received foreign writer in the German catalogue of 1996.10The Frankfurter Allgemeine dedicated the front-page review of their 1996 Frankfurt Book Fair supplement to the “great American author William Gaddis” with a long, laudatory piece by Gustav Seibt (“Die Tonspur…”). Hardly ten years after his unheralded 1987 visit to Germany where he had given talks before audiences of just thirty people, as Dirk Görtler vividly describes in his account of the Freiburg reading.

In a sense, the bulk publication mentioned earlier was itself the result of decade-long neglect. It seems oddly fitting to Gaddis’s career that the real driving force behind the massive publishing effort of the late nineties was the house of Zweitausendeins, a former specialist in selling cheap reprints and remaindered books in their own chain of bookstores in major German cities and, more importantly, a symbol of leftist underground culture since the seventies. Zweitausendeins, up until then, had published the likes of William Burroughs, Bob Dylan, and Robert Crumb, offered marked-down coffee table books on rock stars or whale songs and – seeing themselves as a liberating force in a complacent German society – even literary porn with arte povera chic. Fronting the huge translation costs for Gaddis’s longest novels, then, and throwing in Moore’s Reader’s Guide as a bonus, was a tremendous feat even for the nineties; looking back on it, one cannot but admire the people who took the risk. More than anything else, it meant they trusted their audience. Of course, an underground move like this doesn’t speak well of established literary publishers. The overwhelming impression was that they had simply shied away from the daunting prospect of marketing a foreign writer branded “demanding,” leaving his two longest and most ambitious novels untranslated for decades.

With J R and Frolic entering the German market in 1996, Gaddis became a literary reference point, a status he visibly enjoyed for the last two years of his life. In fact, the translated novels sold reasonably well, and I remember a book presentation in Frankfurt – even without Gaddis’s personal presence – drawing a crowd of beyond a hundred people. The biggest German Gaddis event ever, without any doubt, was his triumphant appearance in Cologne, in the company of his son Matthew, in spring 1997. He was already quite sick by then, and Deutschlandfunk – the radio station which had commissioned the original radio play Torschlusspanik, which became Agapē Agape – paid for first class airfare and medical equipment on board. It’s a crucial part of Gaddis’s German history that large parts of the book we now know to be his last novel were conceived as the monologue of a dying man for the German radio, in translation. Gaddis, in fact, told me gleefully that here for once he had managed to outwit the system: he had been paid well for the radio play in Germany and he also got paid in America for the novel similar enough to be essentially the same book. For the occasion, Barbara Klemm, the renowned staff photographer of the Frankfurter Allgemeine, came over to Cologne and took impressive portraits of the elegant Gaddis, complete with his legendary cane, dapper suit and house slippers, in the lobby of his hotel.11In a letter to Barbara Klemm from 12 July, 1997, sadly not included in Steven Moore’s selection of The Letters, Gaddis wrote:

I have finally just written a note to Paul I. [Ingendaay] marveling at your camera’s evidence that I really was in Cologne, even in the guise of this ‘popinjay’ with his walking stick. That moment, that day, the entire event and reception not only of my staggering self but of my work in Germany has been a sort of rebirth at this late date, and what has made it so was not the commercial ‘book signing’ best-seller here-today-gone-tomorrow American publishing exercise but the very real and lasting warmth of my visit from the moment I arrived through that marvelous Sunday night till the day I left.

On that day in Cologne, William Gass spoke at length on behalf of his friend and colleague, whom he had helped win the National Book Award in 1976 by casting his vote for J R along with Mary McCarthy. The event was hosted by Denis Scheck, then editor of Deutschlandfunk and something like the mastermind behind the whole operation.

Gaddis then spoke to a packed museum hall, listened to the praises of others, didn’t read from his work – he didn’t budge an inch from his routine objection to doing so – and may truly have felt something like a star adored on foreign shores. I like to think he was genuinely moved; his audience, in any case, was. So was the city at large. I recall one of the boulevard papers carrying a story about the, as the headline ran, “mortally sick cult author in Cologne,” a news item he may even have laid eyes on, and relished.

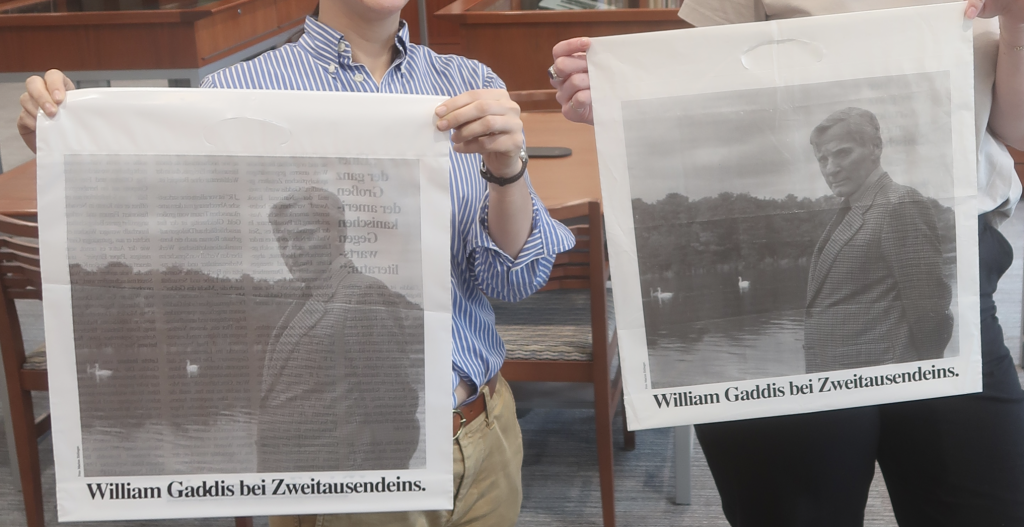

It’s likely it was on that day, too, that Gaddis saw, and touched, for the first time the large white shopping bags Zweitausendeins had had produced in the honor of their cult author the year before. The sturdy plastic things, designed in the austere black and white aesthetics the publisher was famous for, carried Gaddis’s portrait photo, done by Marion Ettlinger, bearing the legend: “William Gaddis bei Zweitausendeins.” On the reverse was a description of his novels excerpted from my own work. In a letter a few months later, again not included in Steven Moore’s volume of Gaddis’s correspondence, he wrote to ask me if it was too much trouble to send him a few more of those plastic bags; some of his friends hadn’t believed him when he told them he had turned into a marketable cultural product in Germany. So, I sent him the five bags I had left, wishing now I had kept one for myself. The ones I sent are likely those now filed with the rest of his archive, in St Louis (see Figure 1).

In his very first letter to me, postmarked 25 August, 1989, he had quoted the brothers Grimm (“my German being shreds of rote from 40 years ago …”) and alluded to Robert Musil’s Man Without Qualities – with the title in German, Der Mann ohne Eigenschaften, “whence we have Mr Eigen in J R …” (Letters 457). Over the years, he mentioned the obvious German sources of inspiration for his books, namely the Faustian myth so important for The Recognitions, or the dwarf Alberich, from Wagner’s Rhinegold, for the unloved, money-grabbing boy named J R. So in Cologne it had an air of higher justice done that Gaddis, finally, had fully arrived in the culture that had provided him with ideas for so long.

Shortly after the fall 1998 publication of The Recognitions under the German title Die Fälschung der Welt (The falsification of the world), Gaddis died in his Long Island home. Long, thoughtful obituaries appeared in all major German newspapers. I wrote one (“Der Stimmenimitator”) for the Frankfurter Allgemeine while staying in Barcelona, Spain, where the news of his death was passed on over the telephone by a colleague who, in my absence, asked the Spanish hotel clerk to take down the important information in writing. When I finally held her hardly legible note in my hands, it read: “Mr Gedis has died.” So much for the transmission of information in the late twentieth century and the implacable ironies of final moments.

Just four months prior to his death, I had visited Gaddis, on two consecutive days, for the last time in his home in One Boat Yard, East Hampton, Long Island. With me was Verena Lueken, then our paper’s New York correspondent. Gaddis talked to us as much as his diminishing powers allowed, with Matthew recording our encounter on film, and asked us to come back the next morning. That Sunday, it took him some time to gather himself and be “presentable,” as he called it. While Matthew helped to prop him up and get him everything he needed, Gaddis kept looking at the weather report on the tv screen, mumbling something about the miseries of old age. That morning was our farewell. I’d have to hunt for my notes of that day to remember what was being said. Mainly, I remember feeling hampered and sad.

For what it is worth, I’d like to finish with a few personal remarks, all bearing on Gaddis’s unique artistic temper. He was, and still is, the writer I admire most among all those I have ever met. Across a time divide of more than thirty years, I have never stopped being a Gaddis reader and a Gaddis fan. Still today, I hold up his novels as models of their kind, knowing that they are probably their own type of kind, or kind of type, following no model whatsoever. There are famous phrases in his novels, much quoted in academic studies, concerning the high task of art within the confines of a commercialized world, from Wyatt Gwyon’s failed artistic mission as a painter to the ever-recurring pursuit of “something worth doing” in the mouth of virtually all his artist characters, especially in J R. He also said it, succinctly and with capital letters for emphasis, in his short piece on the painter Julian Schnabel: “In his relentless search for Authenticity, the artist works to please himself in a constant process of Discovery through the very experience of the making of Art, and then seeking opportunities for it to prevail” (Rush 138). I am convinced Gaddis lived his life emphatically seeking opportunities for art to prevail. All his wit, irony, inventiveness, and formal exuberance went towards this aim with what Joseph Conrad once called “single-mindedness of purpose.”

We all know that “the death of the author” was never meant to suggest his or her disappearance for the reader, or not in the sense I’m talking about here: his or her personality, aura, grace, poise, stubbornness, valor, rage, humor, and intellectual temperature. All these words come to mind when I think of William Gaddis. Not to forget his speaking voice: careful, suggestive of former resonance, a bit hoarse, strained by much smoking in the past. And the ironical chuckle.

There is no doubt in my mind that his late German career gave him great satisfaction. Indeed, it may well be that by not including a number of letters which could have testified to Gaddis’s warm response to all the efforts of his German publishers, translators, and journalist friends, Steven Moore’s edition of The Letters downplayed (certainly unintentionally) the importance of the enthusiastic German reception which had come to Gaddis so late in his life.12See for example the Klemm letter in my footnote 11. In an unpublished letter to me from 10 November, 1996, a few months before the Cologne events described here, Gaddis spoke of his “everlasting gratitude for all your efforts on my work’s behalf going so far back”, and concluded: “I must say I find it quite wild to have my rebirth in Germany! In German! It is immensely pleasing & I am most aware & grateful for, again, all your efforts which have played so important a part.” By then, he had seen the enthusiastic reviews in the German press greeting the simultaneous publication of J R and A Frolic of His Own. On 8 July, 1997, upon receiving a book I had sent him—to the best of my recollection by the Austrian writer Thomas Bernhard—he wrote to me again, speaking generously of “simply another expression of the inventive extra effort you have shown me & my work from the start & some measure of our warm debt since try as you may there is no denying or even mitigating [the fact that] my German publications & that extraordinary Cologne adventure blossomed from your early interest.” In the same letter, he goes on to ask “what may have become of any evidence (tape & otherwise) of that triumphal Sunday evening which, again, will sustain me for this swan song on the player piano.” Of course, that reception could not entirely reconcile him with how his books, at certain times, had fared in the American marketplace. But then, reconciliation wasn’t precisely what he was after. “Never thank them, never complain” was the phrase expressing most succinctly his attitude to reviewers and critics. At his most playful, again with a chuckle, he referred to the recent death of an American reviewer who had thrashed one of his novels: “Gone to his heavenly rewards, such as they are.”

Works Cited

Gaddis, William. The Letters of William Gaddis, ed. Steven Moore. Dalkey Archive Press, 2013.

—. The Rush for Second Place: Essays and Occasional Writings, ed. Joseph Tabbi. Penguin, New York 2002.

Ingendaay, Paul. “Apokalypse im amerikanischen Wohnzimmer: William Gaddis und sein Roman ‘Die Erlöser.’” Süddeutsche Zeitung, Oct 5, 1988.

—. “Der Stimmenimitator. Alles verzahnt: Zum Tod des Schriftstellers William Gaddis.” Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, Dec 18, 1998: 41.

—. “Zauberer ohne Publikum: Versuch über William Gaddis.” Schreibheft 32 (1988): 119-126.

Kirchner, Gerhard. “Satan allein reicht nicht: ‘Die Erlöser’ des Amerikaners William Gaddis.” Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, Oct 4, 1988

Klähn, Bernd. “Der literarische Diskurs der Moderne: Anmerkungen zur innovativen Nachkriegsliteratur der USA.” Schreibheft 29 (1987): 41-47.

Moore, Steven. A Reader’s Guide to William Gaddis’s ‘The Recognitions.’ University of Nebraska Press, 1982.

Raddatz, Fritz J. “Schwarzer Spiegel. Von rigoroser Bitterkeit: William Gaddis’ Roman ‘Die Erlöser.’” Die Zeit, Nov 4, 1988.

Seibt, Gustav. “Die Tonspur einer zerfallenden Welt. ‘J R’: Der große amerikanische Schriftsteller William Gaddis zeigt, wohin es mit der Menschheit im zwanzigsten Jahrhundert gekommen ist.” Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, Oct 1, 1996.