At the Brink: Electronic Literature, Technology, and the Peripheral Imagination at the Atlantic Edge

In this keynote, presented at the 2019 Electronic Literature Organization conference in Cork, Ireland, Anne Karhio highlights the importance of electronic literature as no less peripheral in its own construction of social, cultural, networked communities and material geographies. By looking also at recent scholarship on digital infrastructures, media archaeology, and new materialist approaches to communications technology, Karhio delineates changes that emerge from the margins, "from experimentation and risk-taking that questions established conventions, and canons, and flickers at the border of the actual and the imaginary."

On 15 June 1919, in Clifden, Connemara, the seven-year-old Harry O’Sullivan could not go to Sunday mass as he was sick with measles. He heard a loud roar from above, ran out, and witnessed a Vickers Vimy two-plane aircraft, piloted by John Alcock with the navigator Arthur Whitten Brown, fly past to soon land on, or rather in, the nearby Derrigimlagh Bog. Alcock and Brown had just spent the past 16 hours crossing the Atlantic in dismal conditions, a first crossing of the kind in history. The Irish author Colum McCann imagines their first encounter with Ireland in his novel Transatlantic:

In the distance, the mountains. The quiltwork of stone walls. Corkscrew roads. Stunted trees. An abandoned castle. A pig farm. A church. And there, radio towers to the south. Two-hundred-foot masts in a rectangle of lockstep, some warehouses, a stone house sitting on the edge of the Atlantic. It’s Clifden, then. Clifden. The Marconi Towers. A great net of radio masts. They glance at each other. No words. Bring her down. Bring her down. (McCann 32)

The flight had not been easy, and before seeing the Irish coast below, Alcock and Brown had little idea where they were. It was by sheer luck that they happened to reach the coast near Clifden as planned. In fact, they had not really planned to land in Ireland at all: their desired destination was much less peripheral, the capital of the British Empire, London. But the men decided to play things safe and bring their aircraft down earlier, as they spotted the telegraph towers and saw what seemed like an ideal grassy and even landing strip. As strangers to the Connemara terrain they did not realize that the grass simply disguised an underlying soggy bog, into which their Vickers Vimy prosaically nosedived, as Brown would describe it, “with an unpleasant squelch” (Brown n. pag) This did nothing to diminish the sense of their achievement, however. Locals pillaged parts of the aircraft as souvenirs, to the extent that it “shed more parts after the crash landing than during it”, according to Brendan Lynch (Lynch n. pag.). After a party at Clifden’s Railway Hotel, Alcock and Brown were whisked off to Galway and onwards. These and other the details of the historic landing circulated widely in the media in June 2019, the hundredth anniversary of the crossing (see for example Brown, Cronin, Heather, Lynch, Pope, and Tierney).

Here, the story of Alcock and Brown’s flight from Newfoundland to Connemara prefaces a much larger story of electronic communications and infrastructures, technological change, and the peripheral imagination, and electronic literature’s role in it. The history of media and communications in Ireland has been shaped by its location at the brink of the Atlantic Ocean that lies between its western shore and the North American continent, and has repeatedly made it center and periphery at once, or in quick succession. In 1856, two years before the completion of the first, briefly functioning transatlantic cable connecting Ireland (and thus Europe) with North America, Thomas Knox Fortesque envisioned the Ireland of the near future as a “centre of a collection of radii, whose extremities shall be connected with every country in the Earth” (quoted in Morash 23). At the same time, as Christopher Morash has observed, the “development of the telegraph maps with uncanny precision the years of the famine”: Ireland was as “remote from modernity” as could be imagined, but also “more intimately connected to the rest of the world than ever before” (22-23).

Yet this essay is not “about” Ireland as a pioneer and hub of technological and scientific “firsts”, though there are quite a few of these, or about subscribing to the official government rhetoric around “creative economy and […] enterprise and innovation culture” (Innovation2020 33). Rather, it recognizes that the peripheral imagination extends its gaze to the darker underbelly of technological idealization, the utopian promise of eradicated distance between people and places, and the unsustainable fantasy of endless growth. It also highlights the importance of electronic literature as peripheral imagination by considering it in the context of Ireland’s social, cultural, and material geography, and through recent scholarship on digital infrastructures, media archaeology, and new materialist approaches to communications technology.

The discussion also builds on the conviction that while global information exchanges do not take place within fixed borders or specific settings, they must be understood as economically, infrastructurally, and environmentally situated, even if these sites and situations are perpetually renegotiated. Electronic literature, too, emerges through networks of aesthetic experimentation, but must in its experimentation acknowledge its own responsibility as socially, historically, and politically informed sociocultural practice. This requires building on the two meanings of the phrase “peripheral imagination”: firstly, as the kind of sociocultural dissent that is a prerequisite for literary and artistic creativity, as well as scientific and technological discovery. Change emerges from the margins, from experimentation and risk-taking that questions established conventions, and canons, and flickers at the border of the actual and the imaginary. Secondly, it is the domain of those peripherized, minoritized, and marginalized by social and economic structures of power. Increasingly, we have become aware of how this extends to various non-human or more-than-human forms of being and communication.

Times of rapid transformation in technology and communications tend to recalibrate our sense of centre versus periphery, in aesthetic practice, in cultural production, as well as geopolitically. Joseph Tabbi recognizes this in the context of electronic literature as world literature, and writes that “each successive world-literary formation has been shaped in part by the communications system in place at the time” (Tabbi 28). There is an uneven access to these communications systems, however, and there are uneven levels of agency in their design and implementation. This has been the case in various locations in Ireland’s western coast in particular, inasmuch as they have emerged as manifestations of the Foucauldian “heterotopia”, “capable of juxtaposing in a single real place several spaces, several sites that are in themselves incompatible” (Foucault 25). For electronic literature, such heterotopias present the challenge of bridging the gap between two kinds of peripheral imagination: between meaningful aesthetic and social dissent, and the locating of the marginalized voice. The periphery can be harnessed to challenge prevailing narrative of technological progress, and help imagine its alternatives.

Transmissions

Alcock and Brown’s clumsy landing in Derrigimlagh was not entirely accidental, even if Clifden had not been foreseen as the end point of their flight. The two were well aware of Guglielmo Marconi’s wireless and telegraph station (Figure 1), “the first fixed point-to-point morse telegraphy station, sending ‘marconigrams’ to the new world”, as Michael Sexton describes it (Sexton 16). Mike Cronin stresses that the pilot and navigator were well aware of how from Clifden “news could be spread across the world […] almost instantly”; and “[as] planned, the word of [the pilots’] success was telegraphed around the world, and journalists from across Ireland and beyond sped to Clifden to interview the two men” (Mike Cronin n. pag.). In Connemara: Last Pool of Darkness, Tim Robinson describes the station in a striking passage:

The appearance of the station on its opening for business in October 1907, seen from far away on that level landscape, must have been something like a flotilla of schooners riding out a storm. The transmitting aerial wires were carried on eight wooden masts 210 feet high, each held in place by four stays, in an array that stretched for a third of a mile eastward out into the bog; to celebrate the occasion [of its opening] one mast carried the flags of Britain, the USA, Canada, and Italy [N.B. not Ireland, which was not yet an independent nation]. The noise of the sparks made visitors cover their ears, and flashes as of lightning were visible especially by night. The first few days of operations were accompanied by torrential rain, which according to a Galway newspaper local people blamed on “the penetration of the clouds by the electricity which gives impetus to the Marconigrams”. (Robinson 266)

Marconi’s station placed Clifden within the rapidly expanding global network of electronic communications, “flaunting”, as Brendan Lynch has observed, “the latest technology in one of the most deprived corners of Europe” (Lynch n. pag.). The station’s location in Connemara was chosen due to a combination of geographical and socioeconomic advantage: 18 years prior to Alcock and Brown’s endeavor, Marconi had successfully transmitted the first wireless message across the Atlantic, between Poldhu in Cornwall, and Signal Hill, St. John’s, Newfoundland in Canada. It was due to financial challenges and foreseen opportunities that Marconi subsequently opened the Clifden station in 1907.

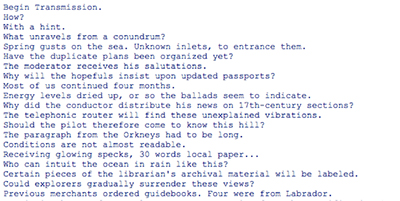

Several other stations were built along Ireland’s western coast. The coast was already the landing point for the first transatlantic telegraph cable (to which I shall return shortly), as well as the point of departure or arrival for countless journeys by fishermen, emigrants, traders, invaders, and explorers. This multiplicity of sociocultural strata co-existing in coastal points of departure and arrival informs J. R. Carpenter’s combinatory text TRANS.MISSION[A.DIALOGUE] (2011, Figure 2), “a computer-generated dialogue” or “literary narrative in the form of a conversation” (Carpenter, “statement”, n. pag.). If, in the age of computational media, Tabbi suggests, the aspiration for a shared language for human literary expression in the system of world literature has been replaced by the idea of inhabiting “a common workspace”, TRANS.MISSION reflects on, and performs, the heterogeneity of this space. And inasmuch as electronic literature has the potential “to disturb the smooth operation of global communications, using textual instruments whose operations are largely conceptual” (26), Carpenter’s shifting, entangled lines demonstrate that this smoothness can itself be an illusion. By implication, literary practitioners in the digital domain must also remain alert to electronic literature’s own operations and margins, and the disturbances at its own social and material periphery.

Figure 2: TRANS.MISSION[A.DIALOGUE] by J. R. Carpenter. Screenshot.

Carpenter explicitly recognizes the significance of how the combinatory text performs itself on the web, and thus not only evokes but also participates in the transmission of signals and narratives across the connections and nodes of the network. It repurposes – and thus translates – the code for Nick Montfort’s The Two (it was first written in python and then translated to javascript) and emerges in-between a series of locations. There is an intimate link between the aesthetic form and the material medium that enables it. Carpenter describes how “One JavaScript file sits in one directory on one server attached to a vast network of hubs, routers, switches, and submarine cables through which this one file may be accessed many times from many places by many devices. Each time this JavaScript is called, the network, the browser, and the client-side CPU conspire to respond with a new iteration” (Carpenter, “statement”, n. pag.). A transmission begins, there is a question or call, a response, and then lines charting the transmission of goods, ideas, texts, vessels, explorers, migrants and histories of oceanic crossing. But the phrases recombine and write themselves again before the reader reaches the end of the page, and she must return to the beginning to start the journey over. Like María Mencía’s cartographic data visualization Gateway to the World (which also has an Irish iteration), and Judy Malloy’s hypertext narrative From Ireland with Letters, Carpenter’s TRANS.MISSION enacts a constantly shifting poetics of migration, transmission, and exchange, where no single version or journey through the text, or across the sea, can stand for all the others.

Figure 2: TRANS.MISSION[A.DIALOGUE] by J. R. Carpenter. Screenshot.

Carpenter explicitly recognizes the significance of how the combinatory text performs itself on the web, and thus not only evokes but also participates in the transmission of signals and narratives across the connections and nodes of the network. It repurposes – and thus translates – the code for Nick Montfort’s The Two (it was first written in python and then translated to javascript) and emerges in-between a series of locations. There is an intimate link between the aesthetic form and the material medium that enables it. Carpenter describes how “One JavaScript file sits in one directory on one server attached to a vast network of hubs, routers, switches, and submarine cables through which this one file may be accessed many times from many places by many devices. Each time this JavaScript is called, the network, the browser, and the client-side CPU conspire to respond with a new iteration” (Carpenter, “statement”, n. pag.). A transmission begins, there is a question or call, a response, and then lines charting the transmission of goods, ideas, texts, vessels, explorers, migrants and histories of oceanic crossing. But the phrases recombine and write themselves again before the reader reaches the end of the page, and she must return to the beginning to start the journey over. Like María Mencía’s cartographic data visualization Gateway to the World (which also has an Irish iteration), and Judy Malloy’s hypertext narrative From Ireland with Letters, Carpenter’s TRANS.MISSION enacts a constantly shifting poetics of migration, transmission, and exchange, where no single version or journey through the text, or across the sea, can stand for all the others.

Importantly, TRANS.MISSION goes beyond aesthetic and formal reflection on transatlantic exchanges: its constantly reiterated lines reach out to, or from, one location after another, adopt multiple voices, and carry a mixed assortment of messages and cargo. The code may not be the text – or all of the text – but here a glance at the work’s code helps illustrate the variety of locations, experiences and materials involved. Transmissions have numerous points of departure and arrival; they are situated in specific material locations or places of personal significance:

[‘Canada’,‘England’,‘Ireland’,‘Scotland’,‘Wales’,‘Cornwall’,‘New Brunswick’,‘Nova Scotia’,‘Cape Breton’,‘Newfoundland’,‘Labrador’,‘the Maritimes’,‘the Scilly Isles’,‘the Hebrides’,‘the Orkneys’,‘the New World’,‘the old country’,‘home’]

Each message is not only geographically situated, but also embedded in a system of communication that has a technological and material, as well as social and cultural dimension. Tools and infrastructures participate in various acts and events of transmission, which search for their own expression in language, appropriate for their communicative function:

[‘electromagnetic’,‘long-distance’,‘ship-to-shore’,‘shortwave’,‘submarine cable’, ‘telegraphic’,‘telephonic’,‘transatlantic’,‘transverse’,‘wireless’]

[…]

[‘advertise’,‘broadcast’,‘communicate’,‘convey’,‘deliver’,‘distribute’,‘post’, ‘receive’,‘relay’,‘report’,‘send’,‘signal’,‘trade’,‘transfer’,‘transmit’,‘televise’]

[…]

[‘archival material’,‘article’,‘ballad’,‘evidence’,‘eye-witness account’,‘headline’,‘journal’,‘narrative’,‘research finding’,‘paper trail’,‘photograph’,‘record’,‘report’,‘rumour’,‘script’,‘transcript’, ‘testimonial’,‘textbook’]

At the same time, underpinning any sociocultural function are the material components of signals, as sound and noise, which intermingle and their own potential in contributing to those unexpected forms and outcomes that disturb the smooth operation of technological design. As material entities, signs and signals encounter other materials that refuse to yield to the fantasy of frictionless communication:

[‘beep’,‘click’,‘harmonic resonance’,‘hum’,‘murmur’,‘noise’,‘pattern’,‘rattle’,‘signal’,‘sound’,‘tap’, ‘tremor’,‘vibration’,‘whir’,‘whine’,‘whisper’]

[…]

[‘blips’,‘disturbances’,‘echoes’,‘feedback’,‘ghosts’,‘interference’,‘patterns’, ‘chimeras’, ‘flashing lights’, ‘ships’,‘sails’,‘shadows’,‘smoke’,‘specks’,‘shapes’,‘static’,‘waves’]

The strong media archaeological component in Carpenter’s work, which recognizes its own medium as it builds on previous, historical media infrastructures, highlights the connection between pre-digital and analogue forms of exchange, and present-day communication networks, without reducing it into a single narrative. The multiplicity and heterogeneity of different forms of transatlantic communication is presented as situated and constantly changing, and as driven by a plethora of desires, fears, needs, and desires. Reading TRANS.MISSIONS through its performance as well as its code highlights its nature as a constantly shifting narrative but also an archive or a database – or a demonstration of how, as N. Katherine Hayles has phrased it, the two are natural symbionts rather than enemies. It recognizes the human destinies driven by varieties of the peripheral imagination: curiosity for new knowledge, search for wealth or power, or fleeing for a better life (or just for one’s life). Each transmission, each venturing out to the sea or calling out to the distant shore has its own push and pull factor, and things are always gained or lost in transmission, or in the translation of words into sounds, or letters into electric signals.

In its disturbing of the seemingly smooth surfaces and operations of communications systems, electronic literature can, and should, also recognize how the shared work space is not one: the scholar, the electronic author, the traveler, the telegraph operator, the programmer, and the refugee occupy this space differently, and have diverging routes of access to it, in the networked as well as the material domain. This has less to do with identity or inclusiveness than it does with the recognition of the differences and discrepancies in usage, access, and ownership of the infrastructures of communication. While our digital media networks and platforms are relatively new, what is not new is how different constraints, and different ability to recognize or mobilize those constraints are encountered by individuals and social groups inhabiting the same spaces in very different ways. One person’s freedom becomes another one’s limitation, and one person’s or group’s vision the decimation of another’s entire habitat. It is for this reason that within the global space of textual circulation, electronic literature, too, is, and should be, understood as situated, no matter how transiently. The aesthetic and formal constraints provided by media tools and platforms, computer languages, and interfaces have emerged through, and continuously shape, specific linguistic, material, geographical, and cultural realities. There is no one network, there are many, co-existing in a wider global assemblage of exchanges of capital, goods, texts, images, narratives, and languages.

The literary and scientific imaginaries of the telegraph

Guglielmo Marconi did not invent the wireless, but he was perhaps the first to realize the technology’s large-scale commercial potential. After the first wireless messages had been transmitted between the Clifden station and Nova Scotia, The World’s Work reporter signaled the importance of the event, noting that “[the] mere wireless bridging of the Atlantic is no new thing. The new thing is the opening of a wireless ‘line’ to the businessof the world”, and that “[the] time may come when the wireless will become suitable for consideration by investors” (“Transatlantic Marconigrams” 9624). The commercial as well as military potential of the technology soon became a reality, and the Clifden station’s closure in 1925 was largely due to damage done to its installations during the Irish Civil War, prompted by a rumour that Britain would be allowed to continue using the station for military purposes after the Anglo-Irish treaty (Sexton 88). As a result, Clifden quickly lost its position as the location of one of the world’s most advanced communications hubs. The railway line was closed down in 1935.

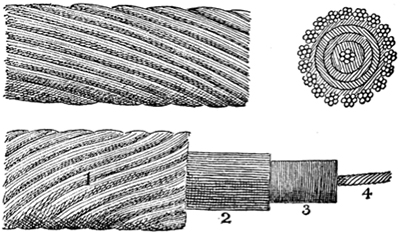

Before Clifden, another west-of-Ireland location had similarly experienced the rise, and would soon experience the fall, in its technological fortunes. Valentia Island at the coast of the Iveragh peninsula in county Kerry, less than two hundred kilometers south of Derrigimlagh as the bird flies, was the European landing point of the first transatlantic telegraph cable. The cable station still stands, but the last telegraph messages were transmitted in the 1960s. The cable, and other submarine cables laid by the Victorians, has become an actual part of the marine ecosystem, like the cable in Figure 3, recovered by CS Cambria in 1906.

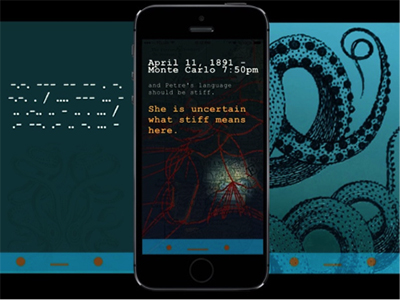

The silence of the cable, the relationship between the Victorian and present-day media ecology, and their co-existence with other social and natural ecosystems have informed Deanne Achong’s mobile app Lusca Mourns the Telegraph | In Search of Lost Messages (exhibited in the Electronic Literature Organization conference in Bergen in 2015, see Achong; Figure 4). The users of Achong’s app are invited to send messages to Lusca, who is dying as she has drawn her strength from the telegraph messages transmitted by the decaying cable, developing feelings while intercepting its signals. Lusca’s own responses to the users’ messages are echoes from the cable’s past, and the dialogue is thus not simply between the reader/user and the creature, but also between the present-day mobile users and those communicating via the 19th century telegraph. Through a wireless, digital messaging technology and a figure that evokes less emotions of gothic sublime than sympathy for those left in the margins of the narratives of progress, Achong’s work highlights the cost of technological obsolescence and marginalization.

Similarly to Achong’s Lusca, the architects of the first transatlantic telegraph struggled for years as they sought the resources required to establish a reliable system of exchange. The first transatlantic cable transmitted the first telegraph messages between Valentia island and the town of Heart’s Content in Newfoundland, Canada, in 1858. After a couple of laborious, costly, yet short- lived attempts, a more permanent connection was finally established in 1866 [an in-depth account of the cable project, including the financial and material resources it required, can be found in Bern Dibner’s 1959 volume The Atlantic Cable (see Dibner)]. It is not possible to outline the process here in much detail, but the sheer amount of hours, capital, and materials committed to the project merits attention. The resources required were by any standard colossal, and justified by much more than passion for scientific knowledge or progress.

These resources can be put in perspective when considered in the context of how, only ten years prior to the first successful transmissions, the west of Ireland had undergone a natural (as well as man-made) disaster of epic proportions, not the first of its kind but brought to the attention of the world through the rapidly growing communications network, as Morash has argued (22-23). Valentia was chosen as the landing site of the Atlantic cable in the aftermath of this calamity, as it was ideally positioned as one of the closest points to Newfoundland, and also offered road and rail transport links east to Dublin and then to London. Much of the island’s much-diminished population continued to live in poverty when the transatlantic cable turned the world’s attention towards Valentia, which quickly became what Cornelia Connolly has described as the 19th century equivalent to the Kennedy Space Centre in Cape Canaveral at the time of the first space and moon flights (Connolly n. pag.).

The contrast between the local economy and the new cutting edge technology is apparent in media coverage of the period: in 1865, one journalist commented on the “strange crowd” of locals, and wrote how “half the men were barefoot, and none of them were decently clad; but all of them, I suppose, could have conversed in two languages,” Irish and English (Connolly n. pag.). Despite such multilingual abilities, the islanders had limited opportunities to become a part of the elite community of professionals and businessmen that mostly profited from the operation of the telegraph, even though the station did offer some benefits and opportunities to the island community (see Buckley, Connolly). The language of the telegraph was English, and its cost beyond the reach of most. In the 1880s, the average weekly salary of an agricultural laborer in Ireland, for example, was up to 12 shillings, and the price of a telegraph message across the Atlantic 2 shillings per word in 1883, down to a shilling per word in 1888 (see Vaughan 320, and Connolly n. pag.). In June 1883, two ships arrived at Valentia harbor and carried 1,200 islanders across the Atlantic to America. Connolly notes how, of the 253 students of the national school on the island, 46 were left after the second ship sailed.

While Valentia was thus in many ways exceptionally well connected and economically advantaged in comparison with other rural communities in Ireland’s west, it was also a site of “competing sets of cultural geographies”, embedded in “broader epistemological spaces”, as Nessa Cronin has argued (Cronin 167). Valentia was, and to some extent continues to be, an embodiment of the variety of transatlantic traffic and exchange evoked in Carpenter’s TRANS.MISSION: it was occupied and traversed by scientists, businessmen, sailors, and emigrants; carrying cargoes of signals, news, maps, ballads, and stories; with cables, ships, boxes, crates, documents, and narratives. This diversity in the media of transmission led to complications in translation, sociocultural as well as linguistic. In 1891, cable engineer Willoughby Smith published his account of the cable project, including a passage anticipating Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, on an encounter with the local oral tradition during a nighttime sea passage to the cable ship The Great Eastern. The passage was interrupted as the local rowers, until then happily discoursing on the cable project, pulled in their oars in fear of evil spirits that were leading them astray. For Smith, this was “an instance of Irish superstition, which, had it not come with my own experience, I would not have believed possible” (Smith 166).

Yet there was no shortage of creative fantasy when it came to the technological future promised by the telegraph, of peace for humankind through the overcoming of distance. The Irish poet Thomas Caulfield Irwin imagined how “[t]hrough swift flashes through the wire as the nerve, over mountain, through main”, “the Telegraph narrows the round of our World to the size of the Brain” (quoted in in Morash 23). This was reflected in visual and cartographic descriptions, which shrunk the Atlantic in relation to the huge Newfoundland and the utterly disproportionate Valentia Island, eradicating most of the distance between Europe and North America. Dibner describes “this new instrument which science had placed before mankind” and how its anticipated “blessings to commerce, industry and statesmanship were exceeded only by its promise as a portent of peace” (Dibner 39). The more sober discussions on military and commercial potential, which largely motivated the investment in the cable project, were overshadowed by an almost religious celebration of its significance for humanity at large. Chester Hearn observes that the cable project inspired “poets, good and bad” (120), with verse such as this vision by Francis Scott Key:

‘Tis done! the angry sea consents,

The nations stand no more apart,

With clasped hands the continents

Feel throbbings of each others’s heart.

Speed, speed the cable; let it run

A loving girdle round the earth,

Till all the nations’ neath the sun

Shall be as brothers of one hearth. (In Dibner, and Hearn 120)

Jones Very’s no less enthralled lines – catalogued under “Religious Sonnets and Poems” in his Poems and Essays, celebrate how “words, with speed of thought, from east to west / Dart to and fro”, and the divine inspiration that made this possible: “May never man, to higher objects blind / Forget by whom this miracle was wrought” (Very 272).

Literary expression was seen to lend cultural authority to technological ambition: creativity and innovation went hand in hand in a manner not entirely dissimilar to 21st century cultural discourse. In his 1916 essay “Poetry of the Telegraph”, Donald McNicol observed how “[t]he telegraph, in its inception, had identified with it men of a high order of literary attainment”, and how “the best poems on the subject have appeared on occasions when a decided advance was made in the appreciation of telegraphy to commercial needs, or when some stubborn obstacle has been overcome by telegraph engineers” (McNicol n. pag.). McNicol goes on to list what for him was the best of “telegraph poetry” written by the date of his publication. But he also lamented how “the excellence of the literary productions of telegraphers during the [eighteen hundred and] seventies and eighties” was in danger of falling into oblivion due to “an overemphasis on educational matters of a technical nature” in published records (McNicol n. pag.). Literary explorations of new technologies were invited to celebrate specific occasions, but were of lesser value for everyday business.

Nicol’s interests emerged from a considerable body of similar examples of pre-digital electronic literature, or, perhaps more often, literature on the new electronic medium. And not all of it remained uncritical of the corporate system sustaining the medium: the Irishman Willian John Johnston, of Ballycastle in County Antrim, (now) Northern Ireland, emigrated to New York to work for The Western Union, the same company that was to take over the Valentia Island telegraph station in 1911, in the late 1860s or early 1870s (see Peterson). After a dispute, he declared himself the sole editor of the biweekly professional paper The Operator, to detach it from the control of the telegraph giant and to serve the noble purpose of giving “telegraphy a literature of its own” (Peterson n. pag.).

The physical cable also stirred the creative energies of the crew of the cable-laying ship of the 1865-1866 missions, The Great Eastern. They published an onboard newsletter called The Atlantic Telegraph, which covered a range of material from letters to editor, news received via the new cable, poems, plays, and so forth. Much of it was intended as entertainment rather than practical information, as creative output offered a counterbalance for the more matter-of-fact brief reports of international news received via the cable itself. Despite being connected to the expanding network of electronic communications, the ship’s crew seem to have envisioned the readership of the newsletter to be limited to those onboard The Great Eastern, sharing the experience of isolation, occasional boredom, and the frustrations brought by the uncertainties of the venture. For example, the heading “Amusements” was followed by dry opening statement “Same as last week.” A mock “Advertisement” listed items for sale, including “The goodwill of The Atlantic Telegraph Company” and “A large quantity of volatile spirits of hope, part over-proof”; “Births” section of one issue reported that of “Sir Optimus Cable” – co-inciding with the death of “the newborn’s father” (Smith 343, 345, 347).

The cable itself assumed, in the literary imaginary of the crew, qualities of a mysterious living organism, with characteristics described in a style that combined the scientific idiom of the period with a kind of Victorian techno-scientific gothic. On 17th August 1865 a short text introduced the fantastic creature of the Cable Worm, Teredo Cablistrius:

[a] singular animal [that] was entirely unknown to the ancients, being called into existence by the manufacture of submarine cables, and showing in all respects the strongest proofs of its parentage. It is greasy and dark in colour, and, from some experiments made by Mr. Varley, it was found if cut into pieces each part was perfect in its electric current, but if a pin was stuck into the whole animal, maliciously or otherwise, the current was broken. (Smith 351)

The “Deep Sea Fishing” section of the 12 August 1865 issue described the cable that previously broke and was lost as a “monster” or “lazy brute” which “lays perfectly still at the bottom of the ocean, and [is] fed by sea animals” (344). On land, too, similar tones and vocabulary of technological sublime and supernatural were often adopted, for example by the American statesman and educator Edward Everett, who imagined the telegraph cable, a “miracle of art”, transmitting “elemental sparks” flashing “far down among the uncouth monsters that wallow in the nether seas, along the wreck-paved floor, though the oozy dungeons of the rayless deep” (quoted in Dibner 20).

But as has happened with most miracles of technology, the telegraph eventually lost its novelty and no longer had similar potential to inspire the scientific or popular imaginary to envision strange creatures and fantasies of peace. As it descended towards obsolescence, the technology co-existing with the “monsters of the deep” fell silent and merged with the environment that hosted it. Achong’s Lusca, tapping into the language otherworldly monstrosity in the 19th century technological imaginary, invites us to consider the human as well as non-human fates of those left in the margins of the narrative of technological progress, but also to see technology as a part of a wider ecosystem.

Digital infrastructures and ecologies at the brink

In recent years, new materialist and posthumanist approaches to examining digital environments have increasingly challenged the rhetoric of 21st century equivalent of Victorian techno-fantasy. They question the language of virtual ephemerality and spatial metaphors, like the “cloud” as a disembodied domain of limitless information exchange. The submerged transatlantic cables of the 19th century telegraph network were a part of the “prehistory of the Cloud” discussed in Tung-Hui Hu’s similarly titled study. A growing body of scholarship also recognizes the cost of unchecked technological growth not only to non-human life, but to entire ecosystems and habitats, as well as what Jussi Parikka has described as “medianatures,” understood as “relation[s] between media and the geophysical environment” (Parikka, Geology 13). This is the “media history of selenium, copper, zinc, dilute sulphuric acid, shellac, silk, wool, gutta percha and various animal tissue used in technical devices” (Parikka, “Electronic Waste”, n. pag.). Technological environments are also natural environments, and their effects extend from the stratosphere to the stony layers of the earth’s lithosphere.

Here, too, Ireland’s past and present are inseparable from the complicated and often uncomfortable aspects of communications infrastructures and economies, at a global scale. The celebration of Ireland’s national technological achievements can obscure the significant socioeconomic contexts and consequences of these events. Alan Gillespie’s characterization of Ireland west, and the Valentia telegraph station more precisely, as “the birthplace of globalisation” is less problematic as an exaggeration than due to the omission of the dark side of this developing global infrastructure. For Gillespie, communications technology “is the one technology from the Industrial Revolution that did not cause mass pollution, unemployment or make working conditions intolerable” (Gillespie 25). This has increasingly been shown not to be the case.

Valentia’s contribution to globalization must therefore also involve a scrutiny of the global communications network’s environmental impact, which predates and anticipates the digital era. One example of this is gutta-percha, a white natural latex that is extracted from the Southeast Asian tree palaquium gutta, a species whose misfortune was its suitability for submarine electrical insulation. Kate Crawford and Vladan Joler’s award-winning research project “Anatomy of an AI System” recognizes palaquium gutta as one of the first victims of the present-day ecological crisis, partially caused by the construction of the modern transport and communications infrastructure. Gutta percha insulation made it possible to protect telegraph cables so they could withstand the conditions of the ocean floor. As the global submarine business grew, so did demand for palaquium gutta trees, and soon this demand became ecologically devastating. Crawford and Joler draw on John Tully, who provides a detailed description of the material make-up of the Atlantic telegraph cable (Figure 2):

The cable that first linked Valentia in Ireland with Newfoundland 1,852 miles away was composed of seven three-eighths-inch copper wires twisted tightly together, each wire individually coated with three layers of refined gutta-percha and minutely inspected for faults to make the insulation and protection from seawater as perfect as possible (Tully 569).

One mature palaquium gutta could yield about 300 grams of latex, and the 1858 transatlantic cable alone required 250 tons of gutta percha. That is the yield of 225 million trees, only for the first, briefly functioning cable. More insulation was added to make up for the costly vulnerabilities of the first cable, and “by the early 1880s the palaquium gutta had vanished” (Crawford and Joler, n. pag.).

Ireland’s own forests had similarly nearly disappeared by the late 19th century, partially to serve another stage of imperial expansion, as raw materials for the British navy, as well as to clear land to feed a growing population. In the 1998 collection Without Asylum, the Irish experimental poet Trevor Joyce drew a parallel between the “murderous intent” of strip mining carried out by “whirring blades”, the “bright axe” of colonial era deforestation, as well as the corporate greed of “firm/controllers.” Joyce, too, situates Ireland at the intersection of developments in technology, globalization, and economic and imperial exploitation.1

The historical and ecological consciousness of Joyce’s poetry and poetics is to a considerable extent informed by his long career in IT. Inasmuch as his writing “addresses the fraught question in contemporary Ireland of the country’s connection to its own past as one of the transmission of data across time”, as Martine Satris has argued (Satris 30), this same fraught question relates to the entangled relations between communications technology, imperialism, gutta-percha telegraph cables, and ecological disasters, which made 19th century Valentia and Ireland the center of scientific achievement. It also calls for an acknowledgement of Ireland’s responsibility regarding the fates of other geographical peripheries in the present day context: the weather observation station that continues to operate on Valentia is one of the world’s oldest. It was opened on the island in 1868, due to the access to the telegraph that allowed for the quick transmission of weather data to overseas destinations. Today, it continues to gather data on the increasingly unpredictable weather on Ireland’s west coast, as the disappearance of forests and the increase in carbon dioxide in the atmosphere are rapidly changing the climate.

The connection between ecocide, climate change, and the network infrastructure have informed several digital literary and art projects, including Joana Moll’s web-based DEFOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOREST (2016). It depicts, in rapidly filling rows of small tree images on screen, the number of trees required to make up for the carbon dioxide emissions from searches via the Google search engine around the world. As Moll’s note on the project states, “Google.com is the most visited site on the Internet. The site has an average of 52.000 visits per second and weights around 2MB, resulting into an estimated amount of 500kg of CO2 emissions every second” (Moll, “Deforest” n. pag.). Moll calculates that canceling the effects of these emissions would require an average of 23 new trees per second. Her CO2GLE (2014) adopts a similar approach, now calculating the amount of CO2 emitted since the last refreshing of the viewer’s browser window. The emissions from the virtual cloud have consequences for very real, material locations, and have a tangible, non-abstract effect on the climate, and again, Ireland plays more than a peripheral role in this process. The country’s low corporate tax rate has been implemented with the specific goal of attracting multinational IT business in mind. The operations of Google, as well as several other multinational IT companies including Facebook, Apple, Microsoft, Dell, and Oracle, have their European headquarters in Ireland, which, due to financial as well as geographical factors, now also hosts a growing number of data centers of these and other companies, like Amazon Web Services. This infrastructure has a considerable impact on the environment, as much of the energy needed to run it continues to be generated from fossil fuels. Works including J.R. Carpenter’s The Gathering Cloud (2016), Shelley Jackson’s Snow (2014 -), or Lisa Robertson’s The Weather (2001) highlight the awkward yet undeniable connections between deforestation resulting from the 19th century scientific hubris, the industry’s hunger for profit from the harvesting and use of limited raw materials, and the overall carbon footprint of 21st century digital infrastructure.

The materiality of the rapidly expanding network highlights the literal dimensions of the spatial metaphors adopted by the ICT industry, covering the entire range of strata within human reach: underneath the atmosphere of clouds, mining takes place in the litosphere, which provides raw material for many of the components needed for the network and its operations: mobile devices, screens, servers, and cables. Between the clouds and the planet’s crust, data centres and bunkers store and transmit signals, data, and information. All of this is also the physical environment hosting various aspects of “supply chain capitalism”, as it has been termed by Anna Tsing (2009). Drawing on Tsing, Evelyn Wang among others has addressed creative interventions into the “chains of exploitation” and the “necropolitics of digital culture” (Wan 1). Molleindustria’s mobile app Phone Story (2011), for example, is “an educational game about the dark side of your favorite smart phone”. The creators urge the player to “Follow (their) phone’s journey around the world and fight the market forces in a spiral of planned obsolescence”, better to understand the consumer’s “complicit(y) in coltan extraction in Congo, outsourced labor in China, e-waste in Pakistan and gadget consumerism in the West” (Phone Story, n. pag.). Similarly, the mixed reality performance LAMENT (The Mine Has Been Opened Up Well) by Judd Morrissey, Jennifer Scappettone and Abraham Avnisan, “excavates”, the artists write, “sites, histories, and languages of mining in a poetics of generative telegraphy, geophysical extraction, and the multilingual hauntings of forgotten laborers” – it critiques “the material substrate of modern network culture, spotlighting labor practices and struggles composing the transnational circuitry of copper” (Morrissey et al, n. pag.).

In Metainterface (2018), Christian Ulrik Andersen and Søren Bro Pold place Phone Story, as well as many of the other works relevant to this discussion, in the context of corporate interests in “the automated protocols for curating cultural software” (Andersen and Pold 49). These protocols and applications “reflect a particular control of cultural consumption […] that is embedded within the technical infrastructures of the prevailing cultural platforms of the metainterface” as an increasingly invisible, yet all-encompassing part of our everyday environment (Andersen and Pold 49). The visual and technological culture of Ireland is deeply embedded in this same system: in another continuation of 19th century developments, tourism and heritage marketing and platforms present Ireland’s landscape through romanticized vistas of green fields, and dramatic coastal sceneries. Ireland’s “literary landscape” is associated with this periphery as a marker of perceived cultural authenticity. But the imagery of Ireland’s Atlantic coastline (or “Wild Atlantic Way”, as it has more recently been branded by the country’s tourism authority Fáilte Ireland) now circulates in that same cloud infrastructure, via the same cables, and between the same data centres that constitute a clear and present threat to the island’s ecosystems.

Importantly, the infrastructure also increasingly exists in the same landscape as the marketed destinations, even if it remains outside the landscape image’s literal and figurative frame, thus calling for situated literary and artistic approaches that push past the established aesthetic. This challenge is taken up for example in the work of the media artist and researcher Paul O’Neill, whose scholarly and creative practice have recently explored how 19th century developments anticipated many present-day issues related to communications technology and infrastructure in Ireland. O’Neill has considered how both cable systems and data center projects are designed to benefit from Ireland’s strategic geopolitical location, and the continuing importance of seeing them in the context of the “complex historical relationships of migration, trade and colonialism.”(O’Neill, “Underwater Cables” n. pag.) Today’s fiberoptic cables and data centers are the material manifestations of how these relationships persistently shape our experiences and perceptions of center versus periphery – socially, economically, and materially. Furthermore, Irish government’s advertising of the country as a global hub of multinational IT operations is in stark contrast to the voiced objection of those whose views are excluded from official strategy documents. A case in point is the Havfrue cable landing station (Danish and Norwegian for “mermaid”) in Killala, county Mayo, opposed by local community for which it was said to be of “no strategic importance” (Mulligan n. pag.). The Irish ESB Telecoms (95 percent owned by the state) that has filed the planning permission stresses that the cable, financed by a huge multinational consortium, has “national strategic significance” (ibid., my emphasis).

These disparate views reflect the uneven effects of what Graham Pickren has described as “the global assemblance of digital flow”: money, data, and energy flow through locations that get their brief moment in limelight in the story of communications technology, until the technology changes or the resources are depleted, or the functioning of the system becomes yesterday’s news and attention turns somewhere else (226). Similarly to the diverging narratives of technology in 19th century Clifden or Valentia, today “the networks of data centres, (undersea) fiber optic cables, routers, and cell towers that power the transmission of digital data marks big data and ubiquitous computing as a palimpsest, a layering of different historical-geographical moments that is unfolding in contingent ways” (226). Pickren’s “palimpsest” is the Foucaultian heterotopia mentioned earlier: different social groups experience the technological event in a shared location in different and often contrasting ways.

Increasingly, the exact functioning and business operations of the digital infrastructure are characterized by considerable degree of political and economic secrecy. As Pickren observes, “invisibility is key to the normalization or ‘black boxing’ […] of socio-technical systems” (229). A black box hides its inner operations from outside scrutiny. The 21st century data centres do not only guard their servers, but also the transactions and processes whereby the stored data moves between individual users, corporations, intelligence agencies, and other interested parties: “Our digital lives and memories are stored within IRL black boxes – massive data centres in industrial estates and business parks around the world,” run by companies like the highly secretive Amazon Web Services (AWS) (O’Neill, “Greetings from” n. pag.). AWS “also works with various governments and operates a ‘secret region’ for US intelligence agencies” (ibid). Joana Moll, in The Hidden Life of an Amazon User (2019) has taken up the challenge of calling out the ethical implications of a system where the gathering of customer data, the secrecy around the location, storage, and exact use of that data, and the environmental impact of this process are impossible to separate (Moll, “Hidden Life” n. pag.). Again, the viewer follows, in real time, the transmission of data, energy, and emissions resulting from Amazon purchases and transactions.

Most multinationals running data centres are somewhat less secretive as AWS, which has multiple centers in Ireland, but AWS raises important questions on privacy, surveillance, public space, and accountability in the data economy. This further relates to the frictions characterizing discussions on data center construction projects, also in the West of Ireland, in Athenry, co. Galway, and Ennis, co. Clare. Paula Gilligan, for example, has discussed Ireland’s data centers particularly in the context of the “Apple for Athenry” data center project, where Apple ultimately withdrew its planning application due to delays caused by local objection (Gilligan n. pag.). As a result, however, the planning process for a center in Ennis is being rushed through the official process, to minimize objection, and with direct references to the delays in Athenry that caused Apple to withdraw their investment. In press coverage, local politicians refer to the data centre as “a goldmine”, and to data as “new oil, the new gold” (Deegan n. pag.). Ennis ticks all the boxes for data centre location: it is close to the Shannon international airport, to the Galway to Limerick motorway, and two power stations – Moneypoint and Ardnacrusha. Its inhabitants, however, have little if any idea as to the exact details of the project, as it is difficult or impossible even to find out which corporation will ultimately operate in the centre. In spring 2019, news reports identified an obscure “Dublin-based firm Art Data Centres Ltd.” as the applicant (Deegan n. pag.). More recent coverage does not name any company involved in the process, only comments about “sensitive” negotiations involving such a commercial venture (Ryan n. pag.).

The gap emerging between the large-scale built environments in public space, and the hiding of their operations from public view informs Moll’s multimedia installation and participatory project*_Hello From* (2010), based on a tailormade app which searches and locates on the map “[c]orporative domains and their hosting servers”, captures a satellite map image of each destination, then printed as a post card and sent via regular mail to the server location. The card is accompanied by “a distorted slogan from the company’s website” (Moll, “_Hello From” n. pag.). Moll’s piece covers corporate domains internationally, but a similarly envisioned tactical media project by O’Neill focuses on data centers in Ireland more specifically. His Greetings From…, presented at the ELO 2019 conference exhibition “Peripheries”, consists of walking tours to data centers, with a final stop at AWS data center in Dublin. In a project that comments on, but moves beyond the imagery of touristic promise of cultural and natural authenticity, participants in O’Neill’s walking tours and visitors to the exhibition have then been encouraged to send messages on postcards featuring a data center to Amazon CEO Jezz Bezos. These creative projects by Moll and O’Neill build on the contradiction that Pickren, too, drawing on Mitchell, highlights: “landscape [becomes] a kind of fetish that can be revealed to embody hidden labour struggles over the means and ends of production” (243). It can also be revealed to embody hidden political and economic structures and interests.

But what is the fate of literary language and literary texts in this system? The economy of literary language versus language as commodity on the web is explored in Pip Thornton’s Poem.py, also included in the ELO 2019 exhibition. The project addresses the exchange and trade of language in the digital economy as a “critique of linguistic capitalism” (Thornton, “poem.py” n. pag.). Poem.py uses Google AdWords to translate or move words from contextualized semantic assemblages in poems to word lists, in which each word is given a price depending on its position in relation to other words, and the current, real-time trading value of this position. Readers are now given the role of paying customers, and offered a printed receipt with a breakdown and total of the value of a poem’s words in the Google word market. Poem.py quantifies the monetary value of language and highlights how, rather than the number of words in an individual telegram, or even the value of quick access to information that attracted 19th century business visionaries, words are now data in a networked system where information on buying patterns, habits, hobbies, travel destinations, or life events is sold for profit. As Thornton notes, “with the near ubiquity of Google’s platforms and advertising empire, which in effect strip narrative context from the words we use while loading them with dissonant capital, it has become almost impossible to critique the system without adding to its economic value” (Thornton, “Geographies” n. pag.). This extends to the difficulty of using the web environment to critique the environmental impact of the web infrastructure.

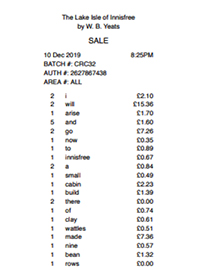

As language becomes data, Thornton argues, it also operates in different “digital geo-linguistic spaces” where it loses its “linear, narrative order” and semantic/referential function on relation to these spaces (Thornton, “Geographies” n. pag.). Language as “digitized data has a wide geographical reach”, but its material existence and circulation in the global digital infrastructure is of a different geographical significance than what scholars of literary cultural geographies would be accustomed to (ibid.). Situating a specific poem in relation to Ireland’s literary and material geography and digital economy helps illustrate he relationship between language, media, and infrastructures of textual circulation. A glance at the words of Yeats’s iconic “Lake Isle of Innisfree” through Poem.py shows how a text widely available on the websites with some kind of connection to Irish literary, culture, or heritage, is now priced according to the contextualization of its individual words within the overall internet economy (Figure 3). Words with specific connection to the actual material or cultural landscape, like “Innishfree” (£0.67), “clay” (£0.61) or “wattles” (£0.51) have a low price, however a seemingly marginal auxiliary verb “will” costs as much as £15.36 – possibly because it is identical to the legal document “will” that would have considerable advertising value on the web. The poem’s centre, the lake isle itself, becomes its periphery in the system of linguistic capitalism. Recognizing the complicated “geographies of context” in the sense they are outlined by Thornton invites us to shift our perspective from representation to a wider social and material framework within which poetic reprentations, too, are now located.

Conclusion

In 1898, Professor G. F. Fitzgerald wrote in the Dublin Evening Mail about Marconi’s wireless technology, and regretted that Wireless Telegraphy “has been looked upon as a thing that ‘no fellah can understand’”; “[i]t is”, he noted, “to be regretted if the Dublin public think so”, as lectures for grasping the technology had been offered to the new generation, and there should be no motivation “to prevent our youth from studying science” (Sexton 116). Such concern over public and the next generation understanding the exact operation of data transmission and storage is increasingly being replaced by a concern over the opposite: the fear that the public might indeed understand how, exactly, the networked infrastructure collects, trades with, and stores our data, where it moves, and to what purposes it is being used. In this context, electronic literature and art, inasmuch as they employ digital tools and platforms as a form of critique from within these media, have a vital role in moving beyond a merely functional understanding of the digital as a merely technical solution, or as methodological novelty in scholarly work.

As well as the constraints and possibilities of the digital medium, electronic literature must find a poetics suited for interrogating the invisible processes underpinning these media. In the current system, situated and locally enacted peripheral imagination is increasingly overpowered by the much less peripheral imagination, advocated as “innovation” in official political rhetoric, where scholarship, science, and creative practice mostly have value when harnessed for greater financial profit. Yet the story of technology, and the stories about technology, could, and can, be different, and electronic literature as critical practice can be employed the direction, function, and design of the expanding infrastructure. It can also allow us to recognize the processes of social peripherization through the peripheral imagination as dissent at a moment when we are, without any doubt, at the brink – literally as well as figuratively in the case of Ireland’s Atlantic coast. The shared workspaces of literary production and circulation in the global communications network present a responsibility to reconfigure those spaces to challenge invisibility as marginalization – and to recognize that we ignore the non-human, or more-of-human domain in which we, too, belong, at our own peril.

Acknowledgements:

Many of the ideas put forward in the above discussion, and the lecture that preceded it, have emerged from conversations, suggestions, and critical as well as creative work carried out by friends and colleagues. I want to particularly credit the research, contribution, and support (in alphabetical order) of Christian Ulrik Andersen, J. R. Carpenter, Paula Gilligan, Anne Goarzin, Sylvie Mikowski, Anna Nacher, Rióna Ní Fhrighil, Laoighseach Ní Choistealbha, Eavan O’Dochartaigh, Paul O’Neill, Søren Bro Pold, Scott Rettberg, Jill Walker Rettberg, Ira Ruppo, Pip Thornton, Álvaro Seiça, and Justin Tonra. I also want to extend a special thank you to James O’Sullivan, who invited me to give this lecture at the ELO 2019 conference in Cork. The research on which this essay builds has been funded by the Irish Research Council.

WORKS CITED

Andersen, Christian Ulrik and Søren Bro Pold. The Metainterface: The Art of Platforms, Cities, and Clouds. The MIT Press, 2018.

Achong, Deanne. “Lusca Mourns the Telegraph”, https://deanneachong.com/lusca-mourns-the-telegraph/, accessed 3 Dec. 2019.

Brown, Sir Arthur Whitten Brown. Flying the Atlantic in Sixteen Hours. Frederick A. Stokes Company, New York. Project Gutenberg, https://www.gutenberg.org/files/47129/47129-h/47129-h.htm, accessed 28 Nov. 2019.

Buckley, Dan. “History Counts,” The Irish Examiner, 4 Apr. 2011. https://www.irishexaminer.com/ireland/politics/history-counts-150264.html, accessed 3 Dec. 2019.

Carpenter, J. R.. TRANS.MISSION[A.DIALOGUE]. 2011. https://luckysoap.com/statements/transmission.html, accessed 3. Dec 2019.

---. The Gathering Cloud. 2016. http://luckysoap.com/thegatheringcloud/frontispiece.html, accessed 3. Dec. 2019.

Carey, James W. “Technology and Ideology: The Case of the Telegraph,” Prospects, vol. 8 (October 1983), 303-325.

Connolly, Cornelia. “The Transatlantic Cable Stations–An Irish Perspective,” History of the Atlantic Cable & Undersea Communications, http://atlantic-cable.com/NF2001/CCPaper/, accessed 3 Dec. 2019.

Crawford, Kate and Vladan Joler. “Anatomy of an AI System: The Amazon Echo as an anatomical map of human labor, data and planetary resources,” https://anatomyof.ai, accessed 4 Dec. 2019.

Cronin, Mike. “Flying into history – Ireland & the story of the first Transatlantic Flight”, RTÉ: Century Ireland, https://www.rte.ie/centuryireland/index.php/articles/flying-into-history-ireland-the-story-of-the-first-transatlantic-flight, accessed 24 Nov. 2019.

Cronin, Nessa. “Maude Delap’s Domestic Science: Island Spaces and Gendered Fieldwork in Irish Natural History,” in Coastal Works: Cultures at the Atlantic Edge, edited by Nicholas Allen, Nick Groom, and Jos Smith. Oxford University Press, 2017, 161-180.

Deegan, Gordon. “Clare council rezones land for €400m data centre outside Ennis,” The Irish Times, 11 Mar. 2019. https://www.irishtimes.com/business/technology/clare-council-rezones-land-for-400m-data-centre-outside-ennis-1.3822069, accessed 7 Dec. 2019.

Dibner, Bern. The Atlantic Cable. Burndy Library, 1959.

Foucault, Michel. “Of Other Spaces,” Diacritics, vol. 16, no. 1 (Spring, 1986), 22–27.

Gilligan, Paula. “‘Visualising Data Centres’ – ‘Apple to Athenry’ and the neganthropocene in Ireland,” presentation at the 2nd annual Critical Media Literacy ConferenceTaking Back the Web: Participation, Panic, Power”, DIT Dublin, October 2018.

Hearn, Chester G. Circuits in the Sea: The Men, the Ships, and the Atlantic Cable. Praeger, 2004.

Heather, Alannah. Errislannan: Scenes from a Painter’s Life. Kindle Edition. The Lilliput Press, 2002 [1993].

Hu, Tung Hui. A Prehistory of the Cloud. The MIT Press, 2016.

Innovation2020: Ireland’s strategy for research and development, science and technology. https://dbei.gov.ie/en/Publications/Publication-files/Innovation-2020.pdf. Accessed 24 Nov. 2019.

Joyce, Trevor. Without Asylum. Wild Honey Press, 1998. http://www.wildhoneypress.com/BOOKS/WAFULL.html, accessed 5 Dec. 2019.

Lynch, Brendan. Yesterday We Were in America: Alcock and Brown, First to Fly the Atlantic Non-Stop. The History Press. Kindle Edition. 1988.

Malloy, Judy. From Ireland with Letters. https://people.well.com/user/jmalloy/from_Ireland/about_whole_top.html, accessed 2 Apr. 2020.

Mencía, María. “Gateway to the World: Data Visualization Poetics.” https://www.mariamencia.com/pages/gatewaytotheworld.html, accessed 2 Apr. 2020.

Moll, Joana. “_Hello From.” Project Website. http://www.janavirgin.com/hello%20from.html, accessed 7 Dec. 2019.

---. CO2GLE. Project website. http://www.janavirgin.com/CO2/, accessed 5 Dec. 2019.

---. “DEFOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOREST”, http://www.janavirgin.com/CO2/DEFOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOREST_about.html, accessed 4 Dec. 2019.

Molleindustria. Phone Story. Project website. http://www.phonestory.org/, accessed 4 Dec. 2019.

Morash, Christopher. “Ghosts and Wires: The Telegraph and Irish Space,” in Ireland and the New Journalism, edited by Karen Steele and Michael de Nie. Palgrave MacMillan, 2014, 21-34.

Morrissey, Judd, Jennifer Scappettone, and Abraham Avnisan. “LAMENT (The Mine Has Been Opened Up Well)”. ELMCIP Knowledge Base description. https://elmcip.net/creative-work/lament-mine-has-been-opened-well, accessed 5 Dec. 2019.

Mulligan, John. “Locals oppose transatlantic cable plan,” The Irish Independent, 13 June 2019. https://www.independent.ie/business/irish/locals-oppose-transatlantic-cable-plan-38214445.html, accessed 7 Dec. 2019.

Neate, Rupert. “12 EU states reject move to expose companies’ tax avoidance,” The Guardian, 28 Nov. 2019. https://www.theguardian.com/business/2019/nov/28/12-eu-states-reject-move-to-expose-companies-tax-avoidance, accessed 29 Nov. 2019.

O’Neill, Paul. “Underwater Cables Leave Ireland Tangled – and Implicated – in the Internet”, https://www.dublininquirer.com/2019/02/20/paul-underwater-cables-leave-ireland-tangled-and-implicated-in-the-internet,accessed 5 Dec. 2019.

O’Sullivan, Majella. “Fortune calls… Joe to realise life’s dream of recovering undersea cable’s treasures”, The Irish Independent, 11 Jul. 2011, https://www.independent.ie/irish-news/fortune-calls-joe-to-realise-lifes-dream-of-recovering-undersea-cables-treasures-26750527.html, accessed 3 Dec. 2011.

Parikka, Jussi. A Geology of Media. University of Minnesota Press, 2015.

---. “Introduction: The Materiality of Media and Waste”, in Medianatures: The Materiality of Information Technology and Electronic Waste, edited by Jussi Parikka. Living Books About Life, 2011. http://www.livingbooksaboutlife.org/books/Electronic_waste/Introduction, accessed 4 Dec. 2019.

Peterson, Britt. “The Golden Age of Telegraph Literature: The 19th-century genre showcased technology anxieties and Catfish-esque storylines”, Slate, 11 Nov. 2014, https://slate.com/technology/2014/11/telegraph-literature-from-19th-century-was-surprisingly-modern.html, accessed 3 Dec. 2019.

Pope, Conor. “Alcock and Brown: Those magnificent men who landed their flying machine in a Galway bog”, The Irish Times, 8 Jun 2019. https://www.irishtimes.com/culture/heritage/alcock-and-brown-those-magnificent-men-who-landed-their-flying-machine-in-a-galway-bog-1.3909415, accessed 24 Nov. 2019.

Robinson, Tim. Connemara: The Last Pool of Darkness. Penguin, 2009.

Ryan, Owen. “Council ‘Confident’ about Ennis Data Centre”, The Clare Champion, 29 Nov. 2019, https://clarechampion.ie/council-confident-about-ennis-data-centre/, accessed 7 Dec. 2019.

Satris, Martine. “Textual Voices of Irish History in Trevor Joyce’s ‘Trem Neul’”, in Essays on the Poetry of Trevor Joyce, edited by Niamh O’Mahony. Shearsman Books, 2015.

Sexton, Michael. Marconi: The Irish Connection. Four Courts Press, 2004.

Smith, Willoughby. The Rise and Extension of Submarine Telegraphy. J. S. VIRTUE & CO, 1891. https://archive.org/details/riseandextensio00smitgoog/page/n1, accessed 7 Dec. 2019.

Tabbi, Joseph. “Electronic Literature as World Literature, or; The Universality of Writing under Constraint,” Poetics Today, vol. 3, no. 1 (Spring 2010), 17-50.

Thornton, Pip. “geographies of (con)text: language and structure in a digital age,” Computational Culture: A Journal of Software Studies, no. 7, 28 Nov. 2017. http://computationalculture.net/geographies-of-context-language-and-structure-in-a-digital-age/, accessed 7 Dec. 2019.

---. “{poem}.py : a critique of linguistic capitalism”, project website, 12 Jun. 2016. https://pipthornton.com/2016/06/12/poem-py-a-critique-of-linguistic-capitalism/, accessed 7 Dec. 2017.

Tierney, Ciaran. “First transatlantic flight ended with a crash-landing in a Galway bog 100 years ago today”, Irish Central, 15 Jun. 2019. https://www.irishcentral.com/roots/history/alcock-brown-first-transatlantic-flight-ireland, accessed 24 Nov. 2019.

“Transatlantic Marconigrams Now and Hereafter”, The World’s Work, December 1907, 9624-9626. https://earlyradiohistory.us/1907ta.htm, accessed 28 November 2019.

Tsing, Anna. “Supply Chains and the Human Condition,” Rethinking Marxism: A Journal of Economics, Culture & Society, vol. 21, no. 2 (2009), 148-176.

Tully, John. “A Victorian Ecological Disaster: Imperialism, the Telegraph, and Gutta-Percha,” Journal of World History, vol. 20, no. 4 (December 2009), 559-579.

Vaughan, W. E.. A New History of Ireland: Volume VI: Ireland under the Union, II: 1870-1921. Oxford University Press, 1989.

Very, Jones. Poems and Essays. Houghton, Mifflin, and Company, 1886. https://ia800602.us.archive.org/35/items/poemsessays00very/poemsessays00very.pdf, accessed 3 Dec. 2019.

Wan, Evelyn. “Labour, mining, dispossession: on the performance of earth and the necropolitics of digital culture,” International Journal of Performance Arts and Digital Media, vol. 15, no. 3 (2019), 249-263.

Footnotes

-

In a final twist to the tale of gutta-percha and the first transatlantic cable, in 2011 The Irish Independent published an article on Joe C. Keating, from Kerry coast near Valentia Island, who is currently salvaging the historical cable from the sea. Apart from the historical context to the operation, the motivation for it is largely commercial, as “the cable is worth a fortune due to its copper, steel, brass, and gutta percha […] components” (O’Sullivan n. pag.). Due to Keating’s alertness, the forgotten cable, and the community that hosted its first laying in the ocean, has resurfaced in an unexpected way. ↩

Cite this article

Karhio, Anne. "At the Brink: Electronic Literature, Technology, and the Peripheral Imagination at the Atlantic Edge" Electronic Book Review, 5 April 2020, https://doi.org/10.7273/1snb-gy96