Gathering screen images and texts shared by artist Les folies passagères on Instagram, Gravel-Patry addresses issues of care that affect women on a daily basis, from mental health to body dysmorphia - but also creating expansive life worlds through our relationality with the digital image, how we operationalize it so that we might think and feel our lives differently.

Introduction

On a light pink background, bodies are floating in space, creating a whirl that circles around the center of the image. In contrast to the visually pleasing color palette, this illustration by Les folies passagères (LFP) is disorienting (figure 1). The bodies represented seem lost in a void, suspended in time and space. In the caption, Maude Bergeron, the artist behind LFP, writes: Dealing with mental health issues on a daily basis is extremely hard. It requires a lot of time and energy. You are not a burden for having some bad days.

For the artist, the illustration represents what it might feel like to live with a mental illness; to be in a constant state of mental fog, or to have your body sucked in by crippling feelings of anxiety. This illustration, and the text that accompanies it, also works as a reminder to her community that there is beauty in the messiness of life and that they shouldn't feel any less worthy because of their illness. The artist's use of the body to represent what happens within the mind sheds light on the physical (though invisible) dimension of mental suffering, as well as the larger entanglement between the surfaces (body, image, representation) and the deeper structures (mind, technology, society). Through the illustrations and texts she shares on her Instagram page, Bergeron addresses issues that affect women on a daily basis, ranging from mental health and body dysmorphia, to sexual violence and racism. Her page is emblematic of a growing number of feminist Instagram pages that deal with mental health and act as support groups where users discuss living with mental illness as it intersects with other forms of marginalization. Not only are these types of illustrations attempting to visualize illnesses that are not visible, they also offer spaces where people can share their stories, seek comfort and share tips with other users. While these pages are undeniably visual, their literary dimension is as much important. This leaves us wondering why women are turning to Instagram, a predominantly visual platform, to share their experiences with mental illness. The question driving this article is therefore the following: What does Instagram allow women to actually do that a text-based platform would not?

In this piece, I argue that instead of using the image platform as a way to ascribe meaning to their feelings, in order to frame the unspeakable, the use of the medium of illustration allows women to consider the possibility of living differently through a relationality with the image. Through this argument, I address the limits of textual analysis, which tends to leave out the sensorial and material dimension of meaning-making, in order to consider other ways that content acquires meaning in a context where image and text collide. More specifically, I am interested in what these practices actually do for women on a personal and political level. I use affect theory as a framework to think about the stuff

that is not always palpable with poststructuralist frameworks of analysis. Textual analysis, though it remains necessary for part of my work, doesn't allow me to get to the crucial dimension of what culture actually does. Using these pages and literatures of care as a case study, I hope to make a broader contribution to the discussion on affect theory, social media and the production of knowledge in a context where images are increasingly central to the way we communicate, share stories and feel our way through life.

I. Affect as Embodied Meaning-Making

I consider pages like LFP as sets of affective practices (Wetherell 17) that articulate different ways of doing care through the operation of the digital image. For Margaret Wetherell, affective practice is the way emotions appear in social life in their messy, eclectic and relational forms. Affect is not only grounded in material lives through bodily reactions, it is embodied meaning-making. For the author, affective practice is "a figuration where body possibilities and routines become recruited or entangled together with meaning-making and with other social and material figurations. It is an organic complex in which all the parts relationally constitute each other.” (17). Drawing from Wetherell, I understand affective practice as the way care gets embodied through media practices that involve both discursive and material modes of doing care. Indeed, according to Wetherell, we cannot separate bodies, talk and text. She condemns the turn to affect of separating affect from discourse and privileging the non-representational as a way out of the socially constructed. However, she holds that the problem with the new work on affect is not its critique of post- structuralism, which is necessary, but the fact that it denies any link between affect and meaning-making. Wetherell further argues that representation is a practical organising activity that we cannot overlook: “Thinking and feeling are, in fact, social acts taking place through the manifold public and communal sources of language.” (21). Social interactions, routines and activities, as well as our reactions in social contexts, are not random (non-conscious) but formed within the social organization of our respective groups. Interestingly, this doesn't mean that our feelings are not real or felt in our bodies, but rather that they are always representational, discursive. Wetherell's explanation is thus an interesting way of approaching representation as the very foundation of our felt everyday lives. It also urges us to consider non-traditional spaces of meaning-making. Building on this, I argue that the routines and relational patterns that are created through the affective practices of care are themselves creating meaning; one that manifests itself not only in signs, codes and icons, but also in the affective textures of the everyday; the contact between bodies; in the traces of the motions of affect.

By flattening mind and body into one image, the illustration I used in the introduction also opens up to the need to talk about the surfaces of body and image. Drawing from the work of Jens Eder, I consider visual communication not just as an aesthetic or semiotic experience, but as a matter of bodily action. Images are particularly effective because they are affective, he argues. Thus, moving beyond a consideration of representation as being superficial and not deep enough

, I rather consider visuality as an integral part of the social and the way we feel our way through life. In fact, Eder argues that images are not just being experienced passively, they operate; meaning they make or augment situations and events.

Image operations, he posits, "are not only operations on images, with images and through images, but also operations by images.” (13). Thus, approaching Bergeron's page as deploying affective image operations is a way to think about the specific forces at play in _Les folies _passagères and the images as potential actors in the doing of care and feminist activism. Indeed, the images are being operated by Bergeron and members of this community in order to do care: following the page, sharing the images, commenting on them, tagging friends in the comments sections or screenshotting images and stories, all translate an affective practice of doing care for oneself and others.

II. The Image as Contact Zone

Through the operation of images, the care page also becomes what Sara Ahmed (96) calls a contact zone, meaning a point of articulation between different objects and bodies that have the potential of creating different affects in the relationality that is being operated. While affect has been theorized as a move away from semiotics and poststructuralism's obsession with signs and structures, both Wetherell and Ahmed highlight the importance of histories, of text and signs, in not only producing meaning, but also affect. Ahmed posits that “knowledge cannot be separated from the bodily world of feeling and sensation; Knowledge is bound up with what makes us sweat, shudder, tremble, all those feelings that are crucially felt on the bodily surface, the skin surface where we touch and are touched by the world.” (171) By taking into consideration the investment of emotions in knowledge, her theories are useful in order to address the erasure of the histories of oppression that are behind the production, circulation and accumulation of feelings especially those associated to women's lives and bodies, and the stigma around mental health. As argued by Ahmed, emotions are relational: we do not have

emotions, but emotions are formed through our contact with things such as images and representations, their past histories and their future possibilities. It is the contingency of that contact that allows affect to become an object, and to in turn produce meaning.

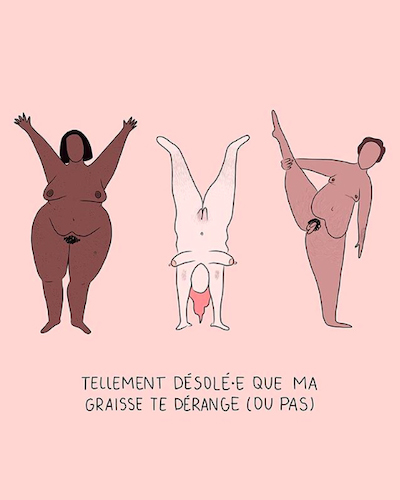

In one illustration, Bergeron uses the word fat (graisse

in French) as something beautiful rather than disgusting (figure 2). By rearticulating the meaning of the word fat, that she associates to images of rounder bodies, the artist is creating different affects. Highlighting what is usually seen as disgusting, such as fat, body hair or period blood, Bergeron uses the image in order to contest the existing visual and textual languages that serve to alienate women's bodies and contain them within a framework of male pleasure. In relations to images such as this one, Ahmed's interest in contact zones and surfaces becomes particularly relevant. According to Ahmed, emotions work to shape the 'surface' of individual and collective bodies.

(1). Instead of trying to make sense only of bodily sensations, Ahmed turns her enquiry towards what it means to be a body in society, how different bodies are interpreted and how bodily traits are used to structure society. The image, and the body, are surfaces to which emotions get attached, but also negotiated through the scaling of affects. By associating different meanings to emotions or physical attributes that are normally associated as negative, Bergeron sheds light on the relationality of emotions and the fact that emotions are shaped by contact with objects rather than simply being in an object (Ahmed 6).

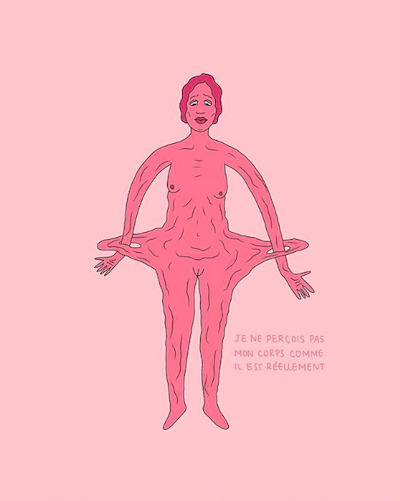

Furthermore, Bergeron's illustrations often evoke the absence of real boundaries between bodies and the world, evoking the vulnerability of people living with mental illness and the material implications of mental illnesses on the body. She often illustrates the body as a porous and elastic entity or a disintegrating pile of mud (figure 3). Far from reality, these illustrations nonetheless offer a visualization of how one's body might feel like when living with mental illness. However, these bodies are not only distorted by mental illness, they also threaten to stick to whatever they touch. This is particularly interesting to understand these in light of Ahmed's notion of stickiness. For Ahmed, stickiness is the effect rather than that which describes the objects' surface. Stickiness is the histories of contact between bodies, objects, and signs.

(90), it is about the meaning that gets attached to certain bodies or objects but also the contingency of that meaning. By representing women's bodies as sticky, Bergeron is shedding light on the difficulties of mental illness, how it can figuratively and physically distort one's perception of themselves, but it also evokes the possibility to reshape this history through the accumulation of new affects. Ultimately, these bodies represent the not-yet

and the contingency of the future that Ahmed describes as the moment of hope, the one that is not-yet shaped by language and the present in which we must act to make it our future.

(Ahmed 184).

III. Inhabiting the Sensorial

But how does that meaning actually get embodied? In an article on images, networked affect and social change, Carolyn Pedwell (154) calls for a more nuanced account of the relationship between images and change especially in a context in which images get shared easily, more rapidly and on a larger scale. She argues that what is required (...) is a mode of critical intervention that addresses the complex interaction of affect and habit within ongoing material processes of transformation.” (154). In reaction to scholars who tend to argue that social media are only affectively binding us into inaction, she argues that the habits we form through our use of social media are actually what allow us to inhabit our sensorial reactions to images. For Pedwell, the interaction between processes of affecting and being affected, and of habituation opens up transformational possibilities:

I suggest that while our affective responses to images can produce a powerful spark that moves us (at least temporarily), affect (...) protracts our relationship with an image (or visual environment), compelling us to inhabit the sensorial intensity of our encounter and its critical implications.(152). However, she argues that without habits, change may appear, but it may not survive. Thus, she understands change not in terms of

affective revolutionsbut rather as something that can happen

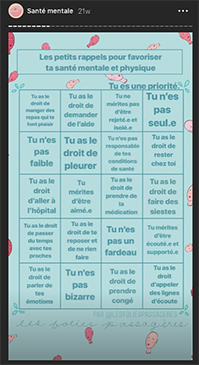

through the accumulation and reverberation of seemingly minor affective responses, interactions, and gestures and habits.(152). As argued by Pedwell, it is through the repetition and accumulation of the image that these habits get taken up. On care pages, the accumulation of images is done mostly through the screenshot. Bergeron invites her followers to screenshot her stories in order to save her to-do lists and it is by screenshotting her images that one can return to them at any time (figure 4). More than just a way of inhabiting the images and the change they represent the screenshot is a way to archive the intensity of the present and keep it with us at any time. Thus, the screenshot is not just a photo of a screen, but it actually embodies the freezing of time and the slowing down of the productive pace of capitalism. In her story highlights, Bergeron shares tips for mental health that she receives from users. Here, she uses the screenshot in order to share the knowledge and make it beneficial to all members of the community (while keeping the identity of the people who share their story anonymous). She also asks questions, through the

ask a question" function of Instagram, in order for them to share their tips on how to deal with anxiety. Bergeron also uses her story to share help-lines and other resources. Through these different ways of operating the story function of Instagram, Bergeron fosters a sense of community and affective inhabitation that gets amplified by her and the community's operation of the image, and scaled through the use of the screenshot. The screenshot is operated in order to foster feelings of community, create solidarity between women and produce collective knowledge. Contrary to the accumulation of viral images to which Pedwell is referring to in her article, literatures of care get inhabited through the intimate circulation of content between members of the community, friends and loved ones.

Though Pedwell's reflections on affect and images are useful in understanding how affective practices of care get inhabited into social or mental change, Pedwell seems to ignore the question of representation and how the feelings we have for images are deeply intertwined with what is represented in the image, as well as social beliefs attached to images themselves. Coming back to Wetherell's argument, I would nuance Pedwell's claims by suggesting that because affect is embodied meaning-making, then we cannot ignore discourse and representation because we are already, always producing meaning in our daily media practices. Implying that representation is not relevant in the study of affect and images only reproduces the idea of an ontological truth that exists outside of language when the reality is that our inhabitation of images depends as much on what is represented and told, than it does on the accumulation of the image itself.

Conclusion

Through this article, I demonstrate that the meaning of these pages is as much produced by the relationality of text and image, the contact between the surfaces of bodies and screens, then it is by the affective textures of these contacts, the sharing of the image and its accumulation over time and space. By putting Pedwell in conversation with Wetherell and Ahmed, the contribution I want to make with this piece is that we cannot dissociate the semiotics of the image from the semiotics of emotions when it comes to understanding how meaning is produced through social media. The affective power of the image, the one that pushes us into action, into actual material changes, resides both in the meaning of the image and its material accumulation as it is shared, screenshotted and inhabited. Women are therefore choosing Instagram not just because it is accessible or because of social prohibitions, but because of what it allows them to create, to do and to feel. Like meaning, the way we understand our bodies and our minds is not fixed, but always in movement, and the creation of expansive life worlds is possible through our relationality with the image; in the way we operationalize it in order to think and feel our lives differently.

Bibliography

Ahmed, Sara. The Cultural Politics of Emotion. Second Edition, Routledge, 2014.

Eder, Jens. Affective Image Operations

in Eder, Jens & Klonk, Charlotte. (Eds.). Image Operations: Visual Media and Political Conflict. Oxford University Press, 2016, pp.63-78.

Wetherell, Margaret. Affect and Emotion: A New Social Science Understanding . London: Sage Publications, 2012.

Pedwell, Carolyn. “Mediated Habits: Images, Networked Affect and Social Change.” Subjectivity 10, 2017, 147-169.