The lively dialogue among the contributing authors, ebr’s longest-serving and newly appointed editors, and the engaged and interested audience, which accompanied the Post-Digital / Dialogues and Debates book launch in September 2020, is an interesting insight into the recent debates on the multifaceted ramifications of digital disruption and the ways in which it has transformed our society, culture, and aesthetics. The discussion throws some light as well on the always fascinating history of the early electronic literature initiatives which had laid the groundwork for what eventually turned out to become the whole new field of intermedia literary practice and the sub-discipline of trans- and interdisciplinary academic inquiry. The authors of the mammoth 2-volume anthology recruit from the variety of contexts and offer diverse looks at the post-digital condition of our contemporaneity.

Zoom book launch September 17th, 2020

Scott Rettberg:

We're very excited to be doing a book launch tonight for Post-Digital: Volume One and Volume Two. Joe Tabbi, who's the editor, is here with us. Just to say a bit about the volumes before Joe gets into it. I wouldn't say it’s the ‘best of’ the electronic book review,’ exactly, but it's a selection of texts from ebr from the past 25 years that the journal has been published.

ebr is one of the leading – and it was one of the first – open access journals in the field of literature. And it really has evolved with digital culture, as academic discourse has begun to be disseminated on the internet, from the mid-1990s and through to the present. I think I can safely say that ebr is certainly one of the most important journals – if not the most important – in our field, and certainly the most important journal for criticism.

I think most of you are familiar with Joe Tabbi. He is a is a well-known critic of American literature who has devoted substantial energy over the years to the development of the field of electronic literature. I first met Joe when we were both living in Chicago 20 years ago – 20 years ago? no, 21 years ago now – it was when we were starting the Electronic Literature Organization. And it was a few years after Joe had begun ebr.

I met up with Joe for coffee. And it turned out that we lived about three blocks away from each other. We talked with each other about these two nascent enterprises and how they might they might fit together. And I'm very pleased that our collaboration has continued to this day. I'm also very pleased that Joe is sort of leading a wave of migration to Norway. We're trying to establish a Center for Digital Narrative here at the University of Bergen. Joe came last year. We're going to be also welcoming a couple of new faculty in January, Jason Nelson and Astrid Ensslin. We've been excited over the years to have hosted so much activity in the field of electronic literature – events like this, that have typically taken place in person; the major ELO conference; and, of course, a very active and robust research group.

I'd like to now turn it over to Joe, who will talk for about 10 to 15 minutes, I guess. And then we'll begin with presentations from a number of people who have published articles in ebr that subsequently became chapters in the book. So take it away, Joe.

Joseph Tabbi:

Thank you, Scott. That meeting over coffee – that was in Leo's Lunch Room on Division Street in Chicago. And you brought a pile of papers that you had just printed out. That was an application for funding the ELO. You had worked with – as I'll say again in my talk here – a couple of others to get that going. And within a matter of months after that Chicago meeting, the ELO had started. So that's just a footnote to that anecdote. Also, I was looking at those present here today and I thought I'd mention that we have two people who were involved in ebr right from the start: Stephanie Strickland and Stuart Moulthrop. Anyone else? Scott and Eric Rasmussen came in a bit later and— Anne Burdick? Is Anne here? Anne was very much present, very close to the start. But we also have three of our recently appointed editors who have joined the journal: Caleb Milligan, Lai-Tze Fan and Anna Nacher. And then we have a number of people who kind of arrived in the middle somewhere: Lisa Swanstrom and Davin Heckman, who have each had sustained terms as co-editors. It’s good that we have so many coeditors present.

It’s what I tried to do with these books, as well: collect not my own selections only, but invite a ‘gathering’ of co-editors who each made selections of their own. As Scott said, it's not a ‘best of’, though it does include a few of my personal ‘bests’ – or, if not best, most relevant and timely pieces. The idea of structuring the volumes this way was to give readers a sense of the cross-section of work in ebr over the decades from a range of perspectives.

The idea for the journal itself occurred to me during a 1993 literary conference in Kassel, Germany that Mark Amerika and I attended. We'd been working together on a special issue of a print journal called American Book Review. That one was founded and edited by Ron Sukenick, Amerika's senior colleague at the University of Colorado. After a post-conference dinner conversation it occurred to me to ask Mark if we might do something similar to what Ron had done with a journal, maybe one designed for the Internet. Mark paused a moment as we were leaving the restaurant, and then he turned to me and said, ‘I might have an idea about how to do that.’

Though we never quite achieved the institutional solidity of American Book Review, which was then part of a formal publishing network called Fiction Collective 2, Mark and I did manage to engage our personal networks, who marked up, illustrated and placed our first issue of – actually, I was going to Google this and see how many essays were in that first issue; it was about 10 – which was posted on the Alt-X website that Mark had founded. He writes about this project in the opening chapter of the first volume.

At the time when we started, there were a number of terms circulating that described the net aesthetic, none of which lasted very long. Among them were these: AvantPop, Surfiction, Chicklit, Critifiction. In retrospect, our terminological gestures toward a digital experimentalism might seem more like a dim echo of modernist movements, avant-gardes, Duchamp and all of that. As Álvaro Seiça, our colleague here in Bergen, argued in an essay for the Bloomsbury Handbook of Electronic Literature (published two years prior to the two ebr volumes), the digital culture tends to discourage collectively recognized movements, their language and identifiers. And that's okay, because our commitments, our aesthetic commitments, were more toward friendships and an early embrace of a kind of networking that was freewheeling and largely unstructured. That was the creative side of ebr that benefited from the incoming experiments of Alt-X members.

We also brought in contributions from the Electronic Literature Organization that was – as we’ve noted – founded by Scott, in collaboration with Robert Coover and Jeff Ballowe. And it's important, particularly now, to recall how easily those of us who were primarily academic scholars could join up with a startup businessman like Ballowe, a postmodern novelist like Coover, and no shortage of creative writers and visual and graphic artists. Consider, for example, the last coinage that we have up in the list of literary terms: ‘critifiction.’ This term was put forward by Raymond Federman, another heterodox literary statesman and a friend of Sukenick, who tended to integrate literary theory with creative writing. This literature/theory convergence was also an important and distinguishing feature of ebr. As Cary Wolfe would argue in his introduction to one of three ‘Critical Ecologies’ gatherings in the new volumes, the spirit that founded and still floats ebr was always along the lines of ‘let's experiment and see what we find.’

And this is also what, for Wolfe, distinguishes ebr’s literary lab – grounded in soft, qualitative and interpretive techniques – from the digital humanities lab, which is more about real or hard knowledge. And for sure, the ability to avail ourselves of an internet that could be accessed freely made many of us feel more like collaborative lab workers than authors, editors or publishers. This transformation of our disciplinary lives was especially noticeable among our first wave of so-called design-writers, who were brought into the journal by Mark America, Steve Tomsula and our early site designer Anne Burdick, who is here today.

I met Tomasula when I arrived at the University of Illinois, Chicago in the fall of 1994. Steve had just graduated with a Ph.D from the creative writing program. You heard me right. Creative writers at that time could – and can now – earn doctorates, which was one of the things I liked best about the program in Chicago, and which is consistent with the sense in ebr that literary studies and literary creativity can go hand-in-hand. That year, ’94, Tomsula had published an interview with Anne Burdick in an arts journal titled Emigré, which was itself an accomplished piece of book art. I remember how it felt to see it and hold that journal. The gallery that Anne has reproduced in Post-Digital gives an impression of the kind of design writing that ebr was featuring at the time, those hybrid processual pages that brought both graphic and visual artists into our literary lab.

So that's one way of describing the uniqueness of ebr that I think still has a lot of potential: the integration of creative and critical writing. To again cite Cary Wolfe, however: even though I can look back and we can say that this is an aspect of the journal's character, there was never a real plan for the journal, no commitment to this or that subject position. And that was certainly true of both the Critical Ecologies thread, that Cary and I initiated and a later, entirely different thread we devised on experimentation in music that happened to interest us. I'll never forget the time when, midway into a brainstorming conversation, Cary was speculating, ‘So, if we do this music sound noise thing—’ I stopped him midsentence, remarking on the acronym Music, Sound Noise: MSN. And that settled that, we had the title: a pun on Microsoft. Later on, we brought in Trace Redell, a practicing musician in digital environments, who would become a colleague of Mark Amerika, to join us as guest editor. None of it – the thread titles or the subject positions or the journal's place within electronic literature or the digital humanities – was ever really formulated concretely. We were mostly playing as we went.

The point of the project – what there was from the beginning and what we have now – is a continuing series of collaborations. A number of these – 16, in fact – are presented formally in the two Post-Digital volumes. Indeed, the selection of essays for reprinting was, for the most part, left to the section editors, the point being precisely to show through a distribution of editorial duties and decisions, a print analog to our formative network structure. A look at the two covers can thus convey a sense of the long list of editors who are joining in and cycling off from one year to the next without a specified term of assignment.

Scott Rettberg:

To give everyone a sense of the contents of the book, we've asked a number of contributors and editors to say some words either about this book or about their experience with ebr. And Eric Rasmussen, who I think is has been one of the longest serving editors, going back to the time when he was a Ph.D student of Joe’s at the University of Illinois at Chicago, will kick us off.

Eric Dean Rasmussen:

First, I just want to thank Joe Tabbi for founding ebr. I joined ebr in 1998, and I think my official title in ’99 was web editor. What I was doing, initially, was marking up essays in HTML. And I met Joe because I'd finished a master's thesis about Pynchon and technology. I'd read and cited his work, and then it turned out that I was living in a neighborhood in Chicago where he was. I'd left one PhD program, thought I was done with academia, was doing different things in the city, and then ebr was what brought me back in. So I've been with ebr now for twenty-some years, and I can say without a doubt that working with ebr has been the most substantive influence on my intellectual development for a variety of reasons. That's no insult to UIC (University of Illinois at Chicago), because while I was at UIC, I was also working at ebr. So I'm grateful for the support that UIC provided ebr at the time, though Joe is no longer there.

ebr has kept me in dialogue with both the e-lit community as well as introduced me to other – what do you want to call it? – posthumanities scholars interested in science, technology, the arts and literature. And it's afforded me opportunities to meet brilliant writers. One of my specialties is American literature and all that includes. Through ebr, I got the chance to record sound poetry with surfictionalist Raymond Federman; to discuss perversion as an ideological concept with Slavoj Žižek; and to interview, with the writers Rone Shavers and Lydia Davis, another prose master and one of my favorite writers, Lynne Tillman. I'm really grateful for all the opportunities, and I'd like to thank Joe and everyone else involved. Thanks for keeping this DIY platform going.

To return to the Post-Digital volumes, my primary responsibility was assembling one of the three Critical Ecology gatherings. Another was done by Cary Wolfe and a third by Laura Shackleford. The one I edited includes seven essays, including my own. What I want to do, then, is explain what ‘critical ecologies’ means and explain two of my primary aims with the essay and the gathering. Basically, if ecology is the study of relations, coming out of biology, between organisms and their environments, then ‘critical ecologies’ at ebr refers to efforts to integrate knowledge produced in the arts and humanities with knowledge from the natural sciences in order to better understand our species' interconnectedness with other non-human entities in shared ecosystems. What's at stake in this? Basically, whether or not our species is going to be able to continue to survive in a biosphere that's severely degraded and damaged. The stakes are high.

Critical Ecologies essays at ebr often discuss and analyze the complex interrelations between integrated systems – and these systems are sometimes textual artifacts – and environments. And these environments are both ‘natural’ and ‘artificial’. I'm glad Anne Burdick is here, because Anne's original site design suggested this integration in the colors that she selected to represent the Critical Ecologies thread: the green and the gray. So there's the integration of environmental ecology – the green – with media technology/ecology and ecology of mind: the gray stands for technology and also for the brain and its extended cognitive systems. You can see just from this cluster of terms how, by working with the system/environment distinction, suddenly you can start to see, to observe, how all sorts of agents in the world act as media forms. What you get from systems theory – this comes from Cary Wolfe – is this idea that we have a broader notion of what communications are. As someone in the field of literature, I'm most interested in language, but we can start to think about all sorts of biosemiotic communications and so on.

My gathering opens with the essay “Literary Ecology: From Resistance to Resilience.” When I'm using the term literary ecology, which has been used before, I'm thinking this way: literary ecology is ecological thinking through practice, via acts of literature. The subtitle, ‘From Resistance to Resilience,’ refers to a phenomenon that I've seen, over twenty-plus years of editorial work, during this digital turn, moving out of the Gutenberg era, which has enabled me to observe larger-scale trends in higher education, particularly the arts and humanities. My first aim with this gathering and my essay was to foreground a subtle but significant shift in critical emphasis. This shift is evident at ebr, but also other affiliated sites and forums, journals and other venues of literary activity, sites where writing is appreciated and examined as aesthetic praxis. Art does something in the world. At the same time, we are thinking about writing as a vital eco-critical activity, literary activity, communicative activity that entails the use of language, words, letters in order to better orient ourselves, our species, within dynamic, turbulent environments. This shift, then, entails a heuristic reorientation from resistance to resilience.

Resistance: we hear this word all the time in literary studies; still, we love it. Resistance suggests opposition, the ability to exert an opposing force. From an ecological perspective, resistance is a quality that enables a system that's being disrupted or under attack to stabilize, protect itself. In this way, resistance is primarily defensive and reactionary (not in a political sense). Now, resilience: resilience also is described as a system's protective responses to disruptions in the environment, but resilience goes beyond preservation or restoring stability and equilibrium. In contemporary biology, the notion of systems remaining in or returning to a state of equilibrium has been challenged. Equilibrium is ephemeral. Resilience connotes adaptability. Resilience refers to a system’s ability to endure these environmental disruptions and protect its integrity while allowing for necessary metamorphoses. I don't need to unpack all this stuff right now with the pandemic going on and wildfiresraging again in California and the West. Some of these things were going on when I first started this gathering in 2017, but the problems just continue to intensify. I'm arguing for the need to develop more resilient systems to adapt to all these changes. I'm particularly interested in literary ecosystems and, not least, publishing systems. You can hopefully see where I'm going with this: I'm thinking about ebr as a literary agent in a larger media-ecological system.

My other aim was to clarify a really important argument, and that's the value of thinking ecologically, via aesthetics, particularly the literary arts. I argue that literary culture – and by literary culture I mean written texts, but also all the processes and practices and activities that are involved in their creation, their circulation, their distribution, their interpretation, their teaching – provides invaluable resources that can help humans and other symbionts to coexist in more healthful environments in this catastrophic new millennium.

One example here: participants in 21st-century literary cultures need to be vigilant when tactically resisting the monopolization of the word by corporations such as Alphabet, Google's parent company, while at the same time adapting to transformations in computational media and complex technical systems. These cognitive technologies, to use a term from Katherine Hayles, a patron of ebr from the start. As Kate reminds us, these cognitive technologies are a “potent force in our planetary cognitive ecology.” They are rapidly changing how we are coevolving with human-technical systems; they are changing the way we process information within environments that are mediated and alter the ways that we act upon the planet.

And this gets us back to the beginning. I'm going to frame it as a question: if publishing systems, both academic and commercial, have been radically disrupted, indeed degraded, by the internet and digital technologies, how can literary studies and literature adapt in what I call the Programming Era? One shorthand answer is we need to maintain and develop existing systems and structures that have proven their value over time rather than pursuing that neoliberal imperative of always chasing after the new, which unfortunately privatized universities and neoliberal 'new' universities often do. One of the things that we need to do, urgently, is to revitalize editorial and publishing systems. And that's one of the reasons why I'm really happy to have been with _ebr all these years and will continue working with ebr for an indefinite period into the future.

Scott Rettberg:

Thanks, Eric, and thanks for all your editorial work over the years. Sort of a hidden engine that keeps things going. I'd like to turn next to Lisa Swanstrom.

Lisa Swanstrom:

Thank you, Joe. And thank you, everyone. And Scott and Davin and Eric and Jill for hosting us, for putting this together. It's wonderful to see faces. It's wonderful to have live conversations about our work, especially now in this kind of weird, surreal time where we are both isolated and completely bombarded with media. It's really nice to take a moment to celebrate and to reflect on the history of, I think, the most important journal online in literary studies and absolutely the most important journal in terms of digital aesthetics in a literary sphere. I'd like to echo what Eric said: I'm very grateful to have been a part and to still be a part of ebr. It's just been a fundamental part of my career and learning and growth as a scholar.

And it was really fun, actually, to go back and read an essay of mine that’s included in Post-Digital, because it was the first piece that I contributed to ebr. I remember when Joe asked me if I wanted to do it, I was just like, ‘I don't know, so much going on; I don't know if I can do it justice.’ Going back to that essay, I realized how much I learned from writing it and how much it has stuck with me in terms of my critical thinking and writing practices. I start that essay with a quote from Flatland – the science-fiction-Victorian novel – from the perspective of a sphere and a square who are trying to reconcile these two completely different modes of existence, two-dimensional and three-dimensional space. And what was so great about that text is that it just provided a nice framing mechanism for everything that the authors and editors are trying to do in that work, which I think is still a concern that we have today, which is how do we talk about these different spaces that, yes, are spaces of representation, but also spaces that we inhabit and interact with in a fully embodied manner, even if that embodied activity differs according to medium. And I think Joe contacted me in 2011. I had just started my first real job; I was still kind of really full of all these ideas from critical code studies – the project that Mark Marino had been developing; and my work as a grad student with Rita Raley, and thinking about ‘Z-space’, was something that occupied my mind for a good chunk of time.

One thing that I take from that experience is that what is so great about ebr – what ebr offers that no other journal that I’ve ever worked on really offers – is the opportunity for improbably improvisational criticism, on-the-fly conversations, real-time responses to media events. And it's actually, after publishing and working with ebr, become much harder for me to work with traditional print publishers, because of the lag time and the intense amount of effort that goes into something that, by the time that it does in fact come out, probably should be restructured because other things have happened in the world, really important things.

I'll close by saying that it's been an honor. Writing for ebr was an essential formative experience for me, as was editing the Natural Media collection with Eric, and editing the Digital and Natural Ecologies gathering. I feel that ebr has been fantastic for helping me develop my editorial practices; I've become a better editor – not of my own work laughs, but a better editor of other people’s work! And I'm very proud of some of the stand-out pieces that we have produced: I was delighted to see, for example, Alenda Chang's ‘Environmental Remediation’ appear in Post-Digital – a of landmark piece that debuted in EBR. My work and training and practice with ebr continues to inform my scholarship. Thank you all very much.

Scott Rettberg:

Thanks, Lisa. I'd like to turn next to Stuart Moulthrop, who is Distinguished Professor of English at the University of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, and is certainly one of the pioneers and continuous innovators in the field of electronic literature.

Stuart Moulthrop:

Thanks, everybody for being here and putting this event together. This is like one of those gatherings of the clans that they do in Scotland. If you've never been on an airplane flying to Europe and discovered that it's full of Americans with Scottish sounding names because they're going up to the clan gathering, that’s really what this feels like. And it's marvelous. I'm learning so much from what you all are saying.

I really want to talk about the piece I have in the volume, which I think is the last piece. And strangely enough – well, maybe not strangely at all – this is about the sixth time, I think, that I've contributed an essay to something and it's been the last piece in the volume, which is either because I'm the kid who always gets picked last for the baseball team or because somehow the things I write feel like, ‘Okay, that's the last word to say about that.’ The latter, I'm sure, is true of this piece. The piece is called ‘Just Not the Future,’ which is actually a quote, and it's one version of an essay that I wrote several times – actually rewrote several times – between December 2016 and September 2017. There's a longer version in a book that came out of something called the Soul International Forum for Literature. So, it's a piece that's evolved many, many ways. The paper belongs to what I hope is a short-lived genre that I will call 2016 trauma pieces.

My piece is a meditation on how to think about one's investment in network media under the image, not of the World Wide Web, but of a Twitterverse haunted by monsters from the Id. I doubt anybody will recognize that phrase, but it comes from a film called Forbidden Planet from 1956 – actually even older than I am – which is one of those films that it's in my personal cinematic brain, Id, I don’t know. Along with La Jetée, which I was fascinated to see come up today. I really need to go see that piece about La Jetée. You might want to go look at it, you know: it's a sci-fi film, a resetting of The Tempest on an alien planet. And there's a reference to monsters from the Id. And I think, in a way, ‘monsters from the Id’ explains far too much about where we are now.

So in my piece, I do this close reading of Whitney Philips’ This Is Why We Can't Have Nice Things, rejecting, with one exception, the prospect of digital disengagement. And Phillips herself also takes this line: that we shouldn't unplug, we need to stay connected. I reach my position in alliance with Phillips, perversely, from the reading of a death-facing poem by someone named Donna Kuhn, whom I didn't know but I found on the internet. This is a poem that she put on a blog, an assemblage of email cut up from correspondence with a friend who was dying from cancer, and at the time that I wrote the piece, I wasn't sure who was dying – whether it was Donna herself or the friend. And I will say that, happily, a year later I got correspondence from Donna Kuhn saying thanks. Anyway, her poem ends with the line, ‘I'm just not the future,’ which is actually coming from her friend. But it also contains the line, ‘I am objectively happy,’ and my essay tries to imagine a way to be objectively and happily disengaged from certain versions of the future.

I'll just wrap up by reading the end of my piece, which goes:

To be happy one must be objective, enforcing a certain separation from spectacularly social media. For some reason, for someone's sins, if not our own, we are doing time in the House of Lies, a place now full of dread, we are doing time in the house of lies, a place now full of dread, though some of us may once have raised a cheer at its raucous, disruptive opening. I will own the memory of that exultation, but not much more. I do not need trolls or Fox or even Oprah in my life. So long as Twitter, Inc. allows the current President of the United States to use its service for defamation and deceit, I will not use that product. Beyond this, total unplugging and other forms of technological asceticism remain unthinkable. Phillips is right: we are mutually in the soup, good and bad alike. Today’s howl—

—and that reference to the soup is from Allen Ginsberg's phrase, ‘the animal soup of time’ in Howl—

Today’s howl comes out differently: if you are not safe for work, I am not safe for work. And still the work continues. Engage we must, but not without stipulations and conditions, the maintenance of an essential and elective distance. Only across such gaps can we gain the perspective needed to figure out why our world is so broken.

Last word: the breakage will almost certainly get worse before it gets better. The 2016 elegies may unfortunately become the 2020 elegies, but you know, we're going to have to deal with it. It may be necessary to disengage from certain futures or timelines – I will call mine ‘Earth 1619,’ referring to the wonderful New York Times piece on slavery – in order to discover better ones. This is the work in which electronic literature and digital art must play an important part.

Thank you and thanks, Scott and Joe, for organizing this.

Joseph Tabbi:

Very quickly, just about the position of your essay at the end of Volume One, I just was noticing that at the end of Volume Two, the last essay is given to Joseph McElroy. So I think you're in good closing company.

Scott Rettberg:

Always good to end on a grim note. Laughter. Let's turn next to someone cheery, always optimistic: Davin Heckman.

Davin Heckman:

As ElectroPoetics editor, my approach was always to just pull in as much material as possible. I think as a young editor, I had no career to speak of, and probably a chip on my shoulder about disciplinary worlds that excluded me, and I had no desire to ingratiate myself to a professional culture that did not want me as myself. So being asked to serve ebr was kind of a godsend to me in my life. And I’ve found that Joe has remained, for all of his grace, wit and charm – to reference a classic work of NetProv – a savvy provocateur. He enjoys hard ideas, always opening himself up to the new, ignoring credentials and going straight to substance. Related to this is an e-lit community that is built by outsiders and self-starters and other nonconformist, talented people changing the world, often fighting for the merest toehold in their disciplines or in the arts. So as a kind of uneasy academic, getting to work with ebr, which started out countercultural and hopefully will remain so, was an opportunity for me to just soak in as much as possible without a commitment to foregone conclusions, without a commitment to a profession, without a commitment to status. My philosophy was just to publish as much as possible, and the less I knew about what I was publishing, the better: everything as a learning curve.

A digression: if you're ever in a position of editorial responsibility, do what Joe does – appoint junior scholars to good positions. Forget about their degrees, forget about fashionable perspectives, forget about prestige. Just give chances to people who have nothing to lose. The humanities don’t need to imitate the sciences. We don't need to be unassailable in our outcomes. We can be questionable. We can be strange. It's important to have a piece of culture that can be admired and assailed. Against the technocratic impulse which has washed over our world, we need to remind people that someone can be simultaneously valuable and interesting, even good, and still be imaginary and contested and unstable and transcendental and fake and satirical, abandoned, whatever.

In the course of this endeavor, I was very lucky to work with Serge Bouchardon, just to point to one example – and he's here, so he'll have a chance to talk about his work. But he's an artist and writer whose work I love. He makes heavy things light. And I was very pleased to discover Serge’s scholarly voice was just as captivating as his creative one. So, I approached him with an offer to rework a scholarly talk into an article, and I was taken aback when he suggested that we collaborate on the piece. The chance to work with someone that you admired for a long time is really special.

Some ideas from that piece – figure; grasp; memory – I looked at his discussion of those things and I found an uncanny applicability to Bernard Stiegler's talk of individuation at the psychic, the collective and the technological level. To think of individual memory as something that's applied to real-time phenomenological being in the world; to think of the social or collective dimensions that frame our interpretations; and then finally to think of the deep cultural memory that’s expressed in institutions, archives, rituals and that sort of thing – to think about works of literature through this framework, we can see the power of instability. We see subjectivity, the self, being as nurtured by a metastable equilibrium that needs both certitude and instability to work. And this is a point, I think, whose salience has only grown as we struggle over social media platforms and their duty to the truth – or what we suspect is their duty to the truth, or we think should be their duty to the truth. We're thrust into a world which is very available to us in two dimensions – the first two dimensions: the psychic and the collective. We can see our individual response to things and we can see what is happening immediately around us, but it’s very closed off to us in the third dimension, which is the archival record and the engagement of the record, which is an analytic project now that is in service of an industrialized model of cultural memory. So we live two lives: we ourselves are increasingly relegated to this kind of ephemeral mode of being, but the larger contours of trans-personal, trans-cultural, trans-temporal thought are part of a digital profile that we cannot easily access or interpret. And I think this has consequences for how we see ourselves. Deprived of perspective, we become more isolated in our perspectives. Social trust decays. We become unforgiving. We lose sympathy. We selectively despise the supposed irrationality of the other. And we become more irrational.

For me, the literary is a powerful counterpoint, and it contains this hope, right? Through its works, e-lit specifically introduces these modes of memory – the primary, the secondary, the tertiary – for consideration. It can engage individuation at these three levels and make us conscious of these things in a way that is hidden from us by the larger industrial apparatus that frames us. So, I just wanted to kind of put that there as my thoughts on what we might be participating in today, or in general – or what we could or should be participating in. And to thank my fellow editors also for giving me so much to think about. Thank you.

Scott Rettberg:

Thanks so much, Davin. One of the great things about ebr, I think, is that it's really been a transgenerational meeting space. I'd like to hear next from Lai-Tze Fan, who is a very bright scholar, a brilliant mind, and a representative from the next generation.

Lai-Tze Fan:

Thanks very much, Scott. I also want to thank Davin for what he’s just said about the human aspect of what we're working on. I think about this in particular when working on aspects of the digital humanities, and I know that Scott and Alex Saum-Pascual just put out an extended gathering in ebr in relation to the digital humanities. That's what we’re publishing right now. Often with topics in relation to technology, we forget about the human. I want to thank Scott, Alex, and Davin for their contributions to thinking about all of this critically. And it’s fitting speaking for me to speak after Davin, as it's because of Davin that I became involved in ebr in the first place, three years ago. He introduced me to Joe in 2017, and they invited me to participate on the board. Joe really took me under his wing.

So, yes, I'm Lai-Tze. I’m the Director of Communications for ebr. I'm the one you hear from every month if you’re getting the newsletters, although that has now changed. We've added a bunch of new editors, which I'm really excited about, and you're going to hear from them as well. And I was really fortunate to become a part of this Post-Digital project, especially because I was added in at the end, through the generosity of Joe. I was asked to write a selected annotated bibliography, which was a tall task. It was really hard to choose texts that could be considered fundamental, because there are so many options. The final product – what actually ended up in the second volume – is only a surface skim, I think, of the wealth of work in e-lit in over 20 years. I was definitely helped by some of the resources that we already offer – the Electronic Literature Directory, ELMCIP. And in building the annotated bibliography, I noticed that a lot of my resources were in English and I really wanted to include e-lit scholarship in other languages. So, while I couldn't read a lot of them – most of them – I wanted to include links of e-lit or e-lit scholarship in other languages, so that they were available to other people all over the world. In that sense, I'm really happy to see how many of you are actually joining us from places all over the world: just going through the chat, I've noted the Philippines, France, Poland, Portugal, Brazil, India, Nigeria, Norway – that's amazing. You're all so welcome; earlier in the chat I said, ‘Welcome to the global community,’ and I definitely mean that. I'm hoping if go forward in thinking about broadening the annotated bibliography – and reflecting a little bit more about what we have to offer on a global scale – that we're going to continue to see a lot of new voices, and newer and older generations, all coming together, collaborating, and coming up with new resources. I look forward to what the reactions are, and to what people have to say.

Scott Rettberg:

Thanks, Lai-Tze. I'd like to turn now to a place and a person who I try to visit at least once a year when there's not a pandemic on. So, my sadness meets the joy of Serge Bouchardon from France.

Serge Bouchardon:

Thank you, Scott. Thank you all. I want to share my screen. Can you see my screen? I know it looks a bit narcissistic, but Scott asked us to talk about our contribution to the books and to ebr, so that's what I'm going to do.

But first of all, I want to say a few words about ebr. I love ebr for its accessibility and readability. But above all, I love the riPOSTes. To encourage continued conversation: this is, for me, a way to revive the ideas of scientific conversation that presided over the invention of journals in the 17th century.

So, since 2012, I’ve published five essays in ebr. The first one, ‘Digital Manipulability and Digital Literature,’ coauthored with Davin, appears in Post-Digital: Volume Two. Davin already spoke so well about this essay, so I will not continue, but I will just focus on one point. The digital is based on the manipulation of discrete units with formal rules, and we link this with the gestural manipulations by the reader of text, image, sound and video. With a digital, as you know, it's not only the medium but also the content as a whole that becomes manipulable. This led me to the notion of figures of manipulation – meaning gestural manipulation – and these rhetorical figures are specific to interactive writing and constitute, for me, a category on their own, along with figures of diction, construction, meaning and thought. The digital makes it possible to defamiliarize the gestural experience inherent to reading and writing; to make it unfamiliar and even strange again.

I continued to explore this notion of figures of manipulation in a paper in 2018, ‘Towards Gestural Specificity in Interactive Digital Literary Narrative.’ As a theoretician and as an author, I'm interested in the ways gestures specific to the digital contribute to the construction of meaning. This question of gestures is also addressed, among other issues, in a paper published in ebr in 2019, ‘Mind the gap! 10 gaps for Digital Literature?’ – which was, in fact, the keynote I gave at the ELO Conference in Montréal the year before.

Then, with my colleague Victor Petit, who is a philosopher of technics – a former student of Bernard Stiegler – I wrote an essay on the philosophical and pedagogical issues of digital writing, based on a project in France. In this essay, we defined the digital as our new milieu – both around us and between us – of writing and reading.

And the last publication, with another French researcher, is entitled ‘The Digital Subject: From Narrative Identity to Poetic Identity,’ and in this essay we offer the hypothesis of a shift in the reader's self-identification process as a poetic experience. We based our analysis both on self-expression processes in social media and on creations of electronic literature.

So, since 2012, ebr, has accompanied my work as a practitioner and researcher, and I want to deeply thank Joe Tabbi, Will Luers, Lai-Tze Fan, Eric Rasmussen and the whole team for that.

Scott Rettberg:

Thanks. I'd like to now ask Anne Burdick just to say a few words. Anne of course, played a very significant role in the design of ebr and has been a significant contributor to many of the threads.

Anne Burdick:

Thank you. I don't have any prepared comments, but I did want to have the opportunity to chime in and emphasize some of the things that I've heard coming through that echo my own experience with ebr. First is to really deeply thank Joe for seeing the potential of design and of the visual representation of writing, the digital representation of writing, as a significant component in the formative years of ebr. What I hear over and over here is about Joe recognizing young scholars or outsider scholars, for lack of a better term, who are engaged in creative and critical work that is relevant to the ongoing development of electronic literature, and _ebr becoming a place for us to really engage deeply and develop our own practice. It was instrumental in my own academic development, and I just can't thank Joe enough for that.

I do remember, in the very early years, meeting once with the group in Chicago in Joe’s loft, and the conversation being about the stakes of the work that we were doing. At the time, I was a design educator, which is a very, very different experience than being an academic in literature. And so, the academic life – tenure expectations and things – was quite foreign to me. But what I heard from my colleagues was that the work that we were all doing collectively was not being recognized and understood by the powers that be in the tenure review process. And that, as I recall Joe putting it, in a sense the stakes were higher for those of us doing this work, because it was a labor of love; we weren’t getting the academic points that we needed, but instead were doing something that we were defining the significance of, and doing in addition to the expected work that was required. So, the Journal – as a site for that investment in a collective, creative and critical project – was developed in spite of academic structures and requirements, and the fact that that work has moved into being understood and validated is really significant. That's pretty phenomenal in my experience.

The other thing that I wanted to say was that for me, in those early years, ebr really allowed me to come to the digital through my interest in writing and in reading – you know, to come at it through writing as the entry point, as opposed to through users or through computation or distant reading or whatever. This was really formative in the development of my own ideas about the role of the digital in the context of reading and writing.

The last little anecdote that I want to share is about a very intense conversation between Ewan Branda, Joe and myself as we were developing the riPOSTe feature and the glossies. You know, what is the entry point of that comment? Is that after a period? Is it after a paragraph? The kind of nitty-gritty questions that have these rippling semantic effects and poetic effects. Being at the site where these things were being hashed out was an incredibly exciting place to be. I was really happy to have been a part of that. So, thank you all for that.

Scott Rettberg:

Thanks so much. I'll just say a few words about my contribution to Volume One here. It was really sort of interesting to me that the Joe asked me to contribute that piece, partially because it was one of the first academic essays that I published in the field of electronic literature, and since then ebr – especially after I was promoted to full professor – has kind of become an intellectual playground for me. Now that I don't need to worry about where I publish something, the first the first question that I ask when I come up with an idea for a strange or an innovative or an interesting project is, Why not publish it in ebr, a great open access journal with a great community of readers, and a place where you can be sort of formally innovative without kind of worrying about the traditions of the older academic journal?

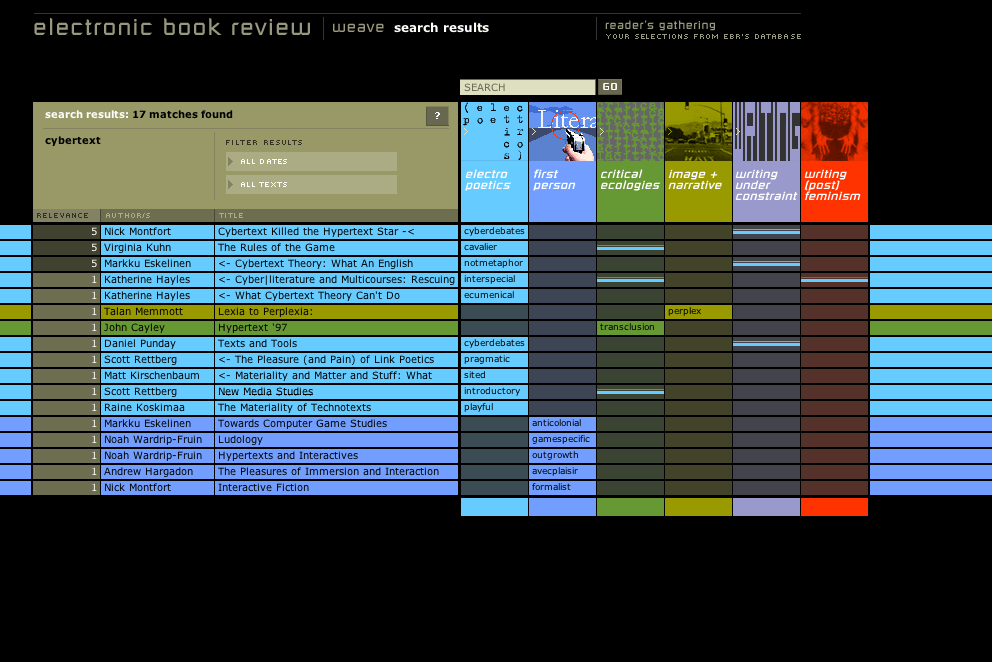

So I’ll just say a few words about this essay, ‘The Pleasure and Pain of Link Poetics.’ This is, as I said, an essay that I wrote when I wore a younger man's clothes. It was right after we had written and published The Unknown – a hypertext novel – and right when I was starting my first professor gig. I was focusing on thinking through the poetics of the link, and this followed an important thread that's documented in Volume One about the ‘cyber text debates’. A number of people – Nick Monfort, N. Katherine Hayles, Matthew Kirschenbaum, Markuu Eskelinen – all contributed to that debate, which grew out of Aarseth's Cybertext and in a way defined the schism between the fields of game studies, or that game studies emerged from, and electronic literature. So I followed a tributary to this debate when Jeff Parker wrote a follow-up that was based on thinking about links and how links function. I won't go through all of this, but I was really interested in this idea, and in following up on some other ideas in ebr about constrained writing, about how the link functions as a constraint and a mode of both reading and writing in hypertext, because when we were writing The Unknown, one of the things that was so exciting to me about the form was the link itself, because it was the sort of poetic device that we didn't understand how to use and whose potentialities we were just exploring. It wasn't just sort of ‘connecting two nodes together’ – certainly that was there, but it was also different ways of being referential, of introducing line breaks, of shifting point of view, of subverting things comically, and of moving around in chronology.

Of course, one of the things about the link, to me, was – and it’s something Stuart's also written about – that it's also an interruption. And for a fiction writer, it's in some ways a problematic interruption. There’s this communicative gap between what the writer intends as a literary effect with the link and how the reader receives it. And again, the really interesting thing to me is that we were not just reading the text, we're reading the gaps between the text when we're reading a hypertext. We're actually kind of reading the links. Links that don't work, that don't pay off, are those that kind of fail to meet a reader's expectation for a sense of connection and causality, or to work against the grain and subvert those in a decipherable way. So, it's not just that we're reading a text, but we're reading intentionality, we’re reading strategy.

One of the things that I reflected on as we were looking through The Unknown and even watching the logs of how people read The Unknown, was that there was this sense of expectation and that it wasn't always about the early rhetoric of hypertext – that hypertext was liberation; that actually links, in some ways, are much more of a direct form of control than the linearity of the random access book, where you can sort of hop around as you choose. But it also creates this interesting anxiety: what am I missing if I don't click? And of course, as a writer, you're a little upset if you write these scenes and you work on them very carefully – in some ways, it's exciting that people want to leap to the next scene, but also, you know, it's sort of sad that they didn't finish the scene to begin with. When we were writing The Unknown, another thing that was fun or exciting about what we did, was that we actually rang a call bell, when we were giving live readings, every time that there was a link. So, it became this really connective mode of performance. And we saw two responses to this at the live readings. One was that people said, Wow! And this was new at the time, right? Hypertext was still relatively new; hypertext on the web certainly was. And people were excited about this, this ability to leap through, and how it was being represented in performance. But other people would come up and say, I was really bummed that we didn't get to finish that scene. Maybe one of the ways that I sort of moved away – although maybe I'll come back to hypertext someday – was this sense that we we were sort of interrupted and unable to tell the story; not that we wanted to tell a linear story to begin with, but there's a loss of control on both sides, from the reader and from the writer.

Hypertext sort of floated off a little bit after the 1990s and early 2000s. But I think it does remain one of the most interesting forms of electronic literature. And that tension between the conflicting desire for movements and contemplation, to me, remains at the core of hypertext, something interesting to think about. That's all I wanted to to say about that essay. And of course, I also encourage you to read the many other essays that I'm publishing, writing and taking part in – including the Framework series about digital humanities and electronic literature – that we're just unfolding now in ebr. Like everybody else, I’m grateful that this venue exists and that this writing community, this intellectual community, continues to thrive.

I'd like to I'd like to open it up now to members of the audience. We kind of predictably went a bit over time, but I'd like to welcome anyone who would like to chime in. Stephanie, do you want to say a few words?

Stephanie Strickland:

Well, we left a lot of things behind. I mean, we're leaving Flash behind, which makes me feel very sad, because the link, I mean, the link wasn't just in hypertext fiction. I know you're mostly doing narrative but, of course, I was much more focused on poetry. And I think it's a whole different story there, a different kind of development, where some things carry over and some things are different. But I do think it all happened so fast, and the changes happened so fast, that it's been very hard to have enough time to really think about what was happening as we move from one thing to the next. There wasn't enough time to have the responses, or as many responses as I think you would have had, if it were a print work. But I'm very grateful for the number of them that we did have in ebr. Anyway, it's been a good ride.

Scott Rettberg:

Thanks very much. I want to thank all of you for coming tonight. I do want to say that one of the things that we've typically done here with our research group is have events, small seminars on various topics, and that a lot of people have been to Bergen to take part in these events, and during the pandemic, of course, we've not been able to do that. So it has been great to have this opportunity. And I think we're going to try to continue to do some of these virtual events, maybe a few each semester. I'll send an announcement to all of you who joined this event about the next event that that we have planned as we firm up the dates. And thanks to all of you for joining from so many places. I think every continent but Antarctica was represented here. So, thanks to all of you for joining us. And I hope to see you on Zoom soon. Even more, I hope to see many of you in person at some point in the future. Stay safe, everyone. Good night or good morning to all.

Joseph Tabbi:

Good night.