Towards Gestural Specificity in Digital Literature

In this essay, Serge Bouchardon looks to electronic literary and its important predecessors in a way that prioritizes gesture and manipulation. Bouchardon interrogates how technology alters and opens the way that literature can be materially engaged-with by its readers, a way that deliberately encourages its readers to engage physically and agentially with the text. In this way, Bouchardon reveals a way of critiquing electronic literature that expands upon the physically-engaging properties of print.

The gesture of manipulation in digital literature

In the domain of digital or electronic literature1, interactive works have already existed for several decades. In an interactive creation, manipulations by the readers are often required so that they can move through the work (for instance in hypertextual narratives). Such manipulations, in these interactive digital creations, are not radically new and there are many examples of literary works which require physical interventions on the part of the reader; for example in Raymond Queneau’s Cent mille milliards de poèmes the readermust construct sonnets from a number of individually printed lines of poetry. Espen Aarseth proposes the term “ergodic literature” to describe this kind of works, arguing that “in ergodic literature, nontrivial effort is required to allow the reader to traverse the text” (Aarseth 1997, p.1). Yet while some print works do require that the reader provides some physical input, what is somewhat new in interactive digital works is the fact that it is the text itself, and not only the physical medium, which acquires a dimension of manipulation. A digital text, as well as being a text provided for reading, can also afford an opportunity for manipulation. This dimension of the manipulation of the text, but also the whole range of semiotic forms, opens a large field of possibilities in interactive digital creations.

But to what extent can one speak of a gesturality specific to the Digital?2 I will focus on three of my own creations to try to answer this question.

Gesture and materiality

Since 2013, a research and creation project has been conducted in partnership with the ALIS company and the University of Technology of Compiegne in France (UTC). The project builds on an artistic practice invented by Pierre Fourny, founder of ALIS, entitled Two Half-Words Poetry (or Cutting-edge Poetry…). This particular practice makes it possible to create sequences based on the idea that words which are halved horizontally, contain the half of other words.3 This poetry is meant to be performed on stage.

Within the context of the project, several interactive applications (for PC and smartphone) have been developed.

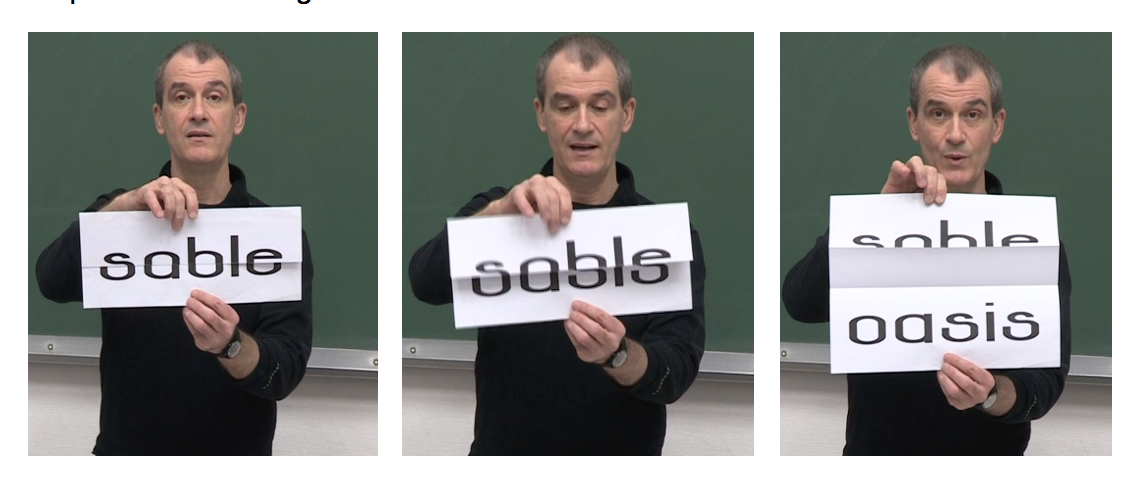

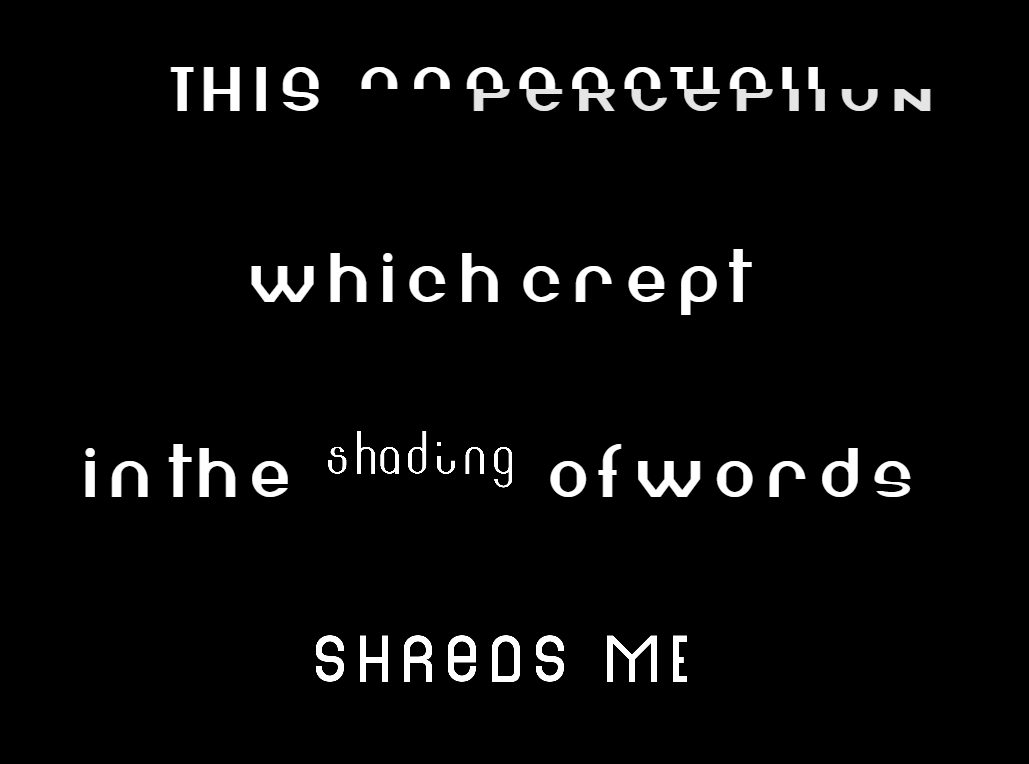

In the application entitled Separation4, the users can experience cutting edge poetry. In the example below (see figure 3), there are three different gestures (with the mouse on a PC or the finger on a smartphone or tablet) and three different animations. With the Guillotine font, the users can cut a word in half (in figure 3, the word “separation” is being cut and the word “perception” takes its place). With the shadow font, they rub a word to let another word appear. With the central font, they tear the word apart.

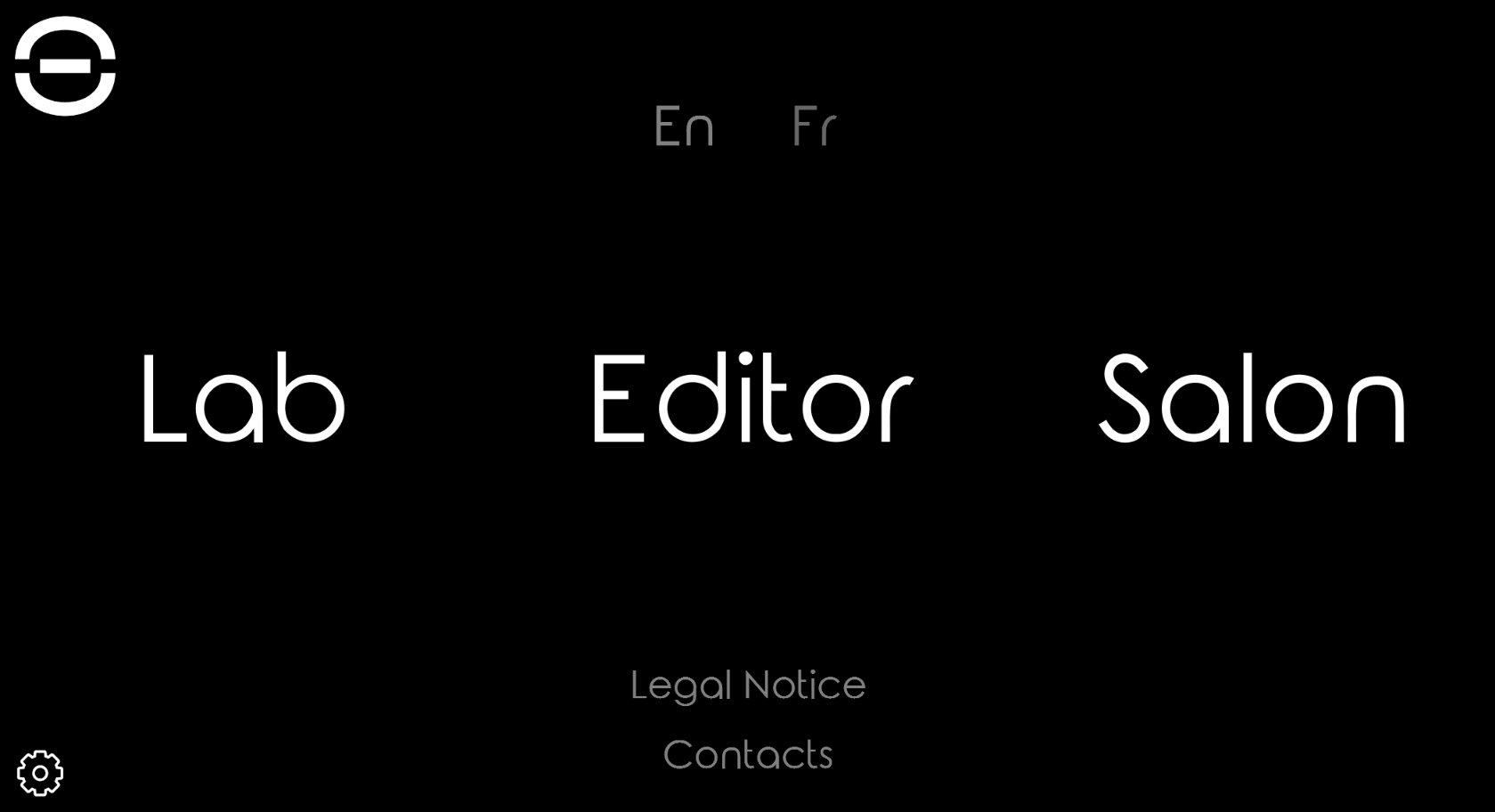

The users of the application are also able (in the “Lab” and “Editor” sections, see figure 4) to play with their own words and texts. A software program returns results dynamically for any word. They can compose their own texts and share them.

The conception and the development of this application, under the form of a prototype, has opened up new avenues about gestures and the production of meaning, especially on interactive mobile screens (smartphones and tablets). The interactive application acts as a call for gestures to be renewed and shared by the users. The semantic choices and gestures of Pierre Fourny, who unveils one word after another on stage, are displaced in the interactive application by the semantic choices and gestures of the user. The user makes the words appear and a poem unfold.

The nature of the gestures themselves is no longer the one that Pierre Fourny has been experiencing so far in the physical space of the stage. The user triggers another realm of possibilities in the tactile digital space. It is impossible indeed in the physical world to cut a word with a simple movement of the finger (see figure 5).

This raises the question of tangibility and the role of materiality in digital writing. We can often experiment on the screen (in the animations of cutting edge poetry) a pragmatic loss of the poem. This loss can be partly compensated by a dramaturgy emphasizing the appearance / disappearance (with movement and speed), important for the perception of the targeted poetic effect. There are also pragmatic gains on the screen, with various possibilities of decomposition of the action that may lead to a more complete perception of the visual process.

Beyond the question of animation, different forms of tangibility can be noted when switching from paper to screen. The gesture of cutting a word in two halves gives the user the illusion of perception through touch. Thus, cutting a word with his/her finger, dragging it to the left or to the right, controlling the speed at which he/she does it, gives the user the impression that his /her finger is actually magnetizing one half of the word.

However, in the Separation application, it may not be appropriate to speak of tangibility in the full sense of the term because there is no mobilization in the interaction of the actual physical constraints and properties of the object: impenetrability, weight, friction… Speaking of tangible user interface would be a misnomer: the idea of tangible user interface is usually to give the user the ability to interact with digital objects through direct manipulation (a reproduction of touching where there is no mediation between the body and the object). But in the smartphone interface application, there is an illusion of tangibility: the user moves objects with his/her fingertip as he/she would move some physical objects (for example a pawn on the squares of a game board). Even though they are not fully tangible, words in the Separation application are manipulable in their materiality.

The exploitation of materiality in digital writings, theorized notably by Katherine Hayles (Hayles, 2008), allows us to do away with the immateriality of the Digital. With the Digital, it is possible to manipulate the medium but also the content, insofar as the content is calculable: materiality found in the digital medium may thus have different properties than in other media. Digital writing leads us to a conception of materiality which is primarily action-based.

Gesture and meaning

Yves Jeanneret (2000) claims that the simple act of turning the page of a book “does not suppose a priori any particular interpretation of the text.” However, “in an interactive work clicking on a hyperword or on an icon is, in itself, an act of interpretation” (113). Jeanneret further suggests that the interactive gesture consists above all in “an interpretation realized through a gesture” (121). However, the distinction that Jeanneret proposes between turning a page and clicking on a hyperlink is not necessarily obvious and could be criticized. Moreover, we are stretching the limits of interpretation quite dramatically if we really accept that all clicking is interpretative. Despite these caveats, we can nevertheless point out that, in an interactive work, the gesture acquires a particular role, which fully contributes to the construction of meaning.

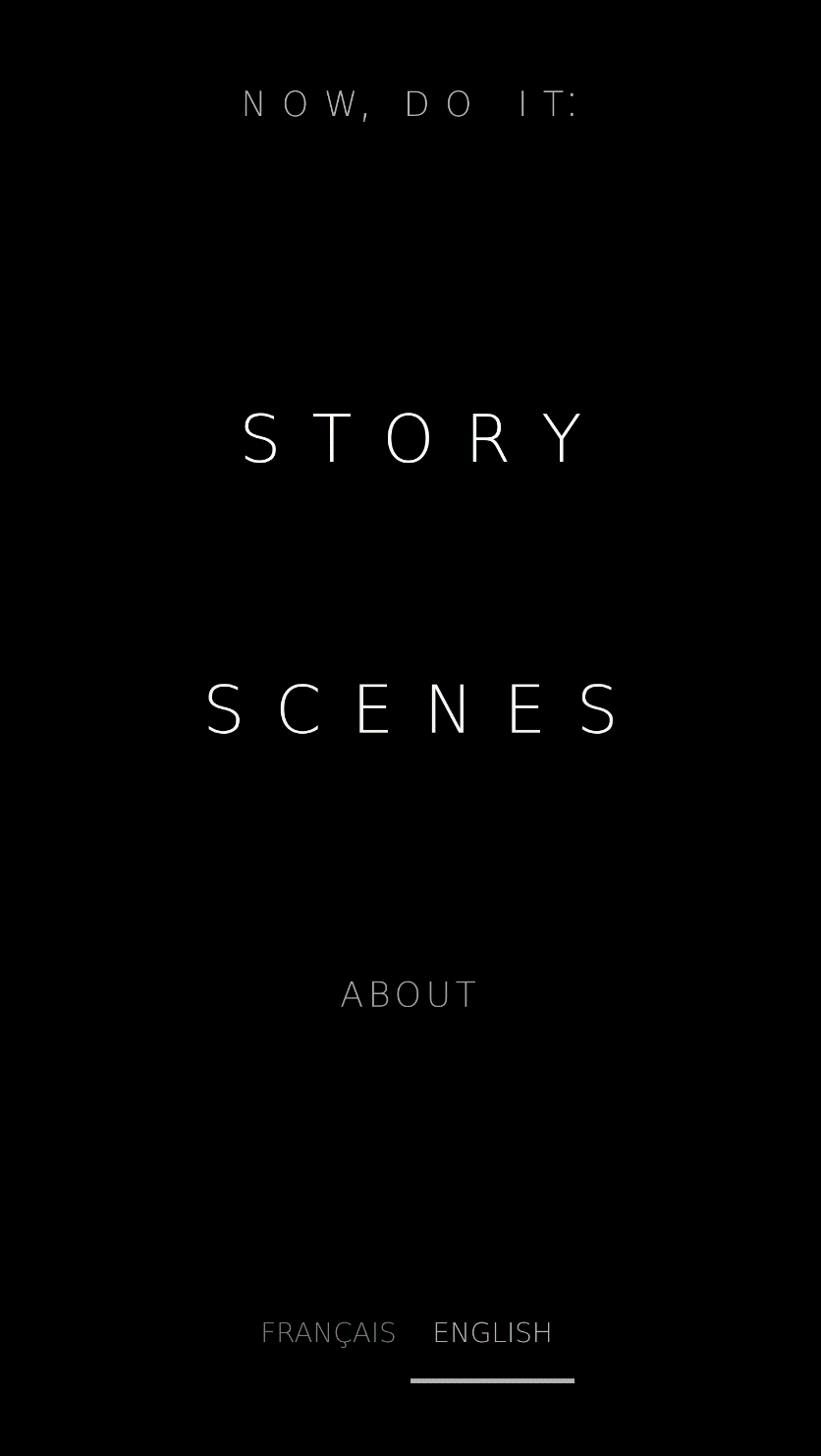

This is the case in the interactive narrative DO IT5, presented in the ICIDS Art Exhibition 2017. This digital creation offers four interactive experiences: adapt, rock, light up and forget. Each scene comes as an answer to contemporary injunctions: being flexible, dynamic and mobile, finding one’s way, forgetting in order to move forward… These four scenes are integrated into an interactive narrative (Story). They can also be experienced independently (Scenes, see figure 6).

The interactive narrative tells the story of someone who is struggling against the acceleration ot time and the injunctions to move always forward, faster and faster. The original music emphasizes the contrast between the reflections of the character, who aspires to slowness, and the injunctions given to him to go always faster and to accelerate the tempo.

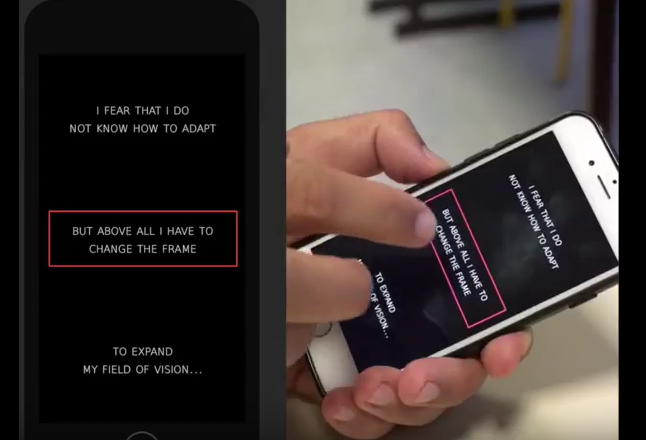

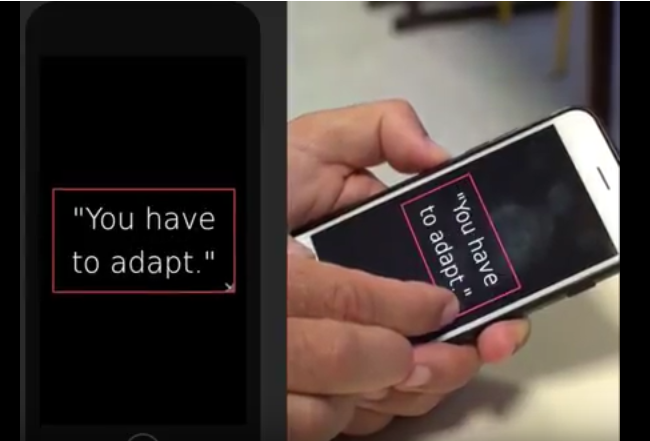

At each stage of the story, the gestures of the user contribute to the construction of meaning. Let us take the examples of the first two scenes. In the Adapt scene6, the character wants to « change the frame to expand [his/her] field of vision » (see figure 7). The user can thus play with a red frame to enlarge it and make the text appear on screen (see figure 8).

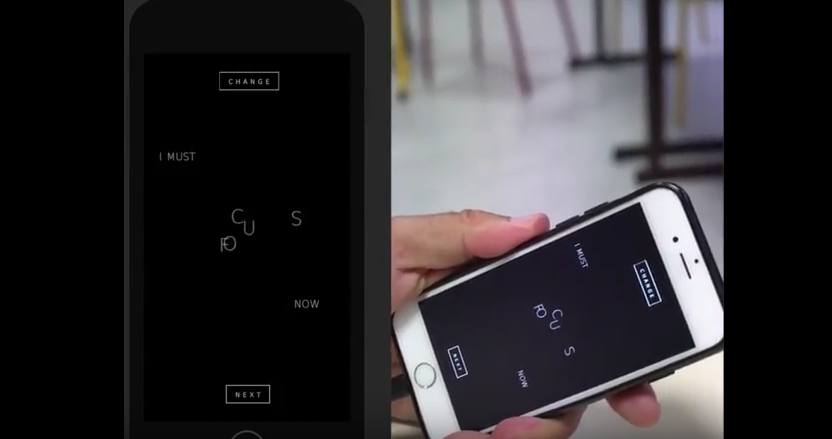

In the Rock scene, the character has to prove that he/she can be dynamic. The user can then shake the mobile phone—more or less strongly—to shake words and let other words appear – with a more or less negative meaning (see figure 10).

In this example, we can see that the user’s gestural manipulations can fully contribute to the construction of meaning.

Gesture and figures of (gestural) manipulation

Numerous interactive works of digital literature, notably interactive narratives, do largely call upon what we may call figures of manipulation (Bouchardon, 2014). Since Antiquity, the figures have been a significant part of rhetoric, even though rhetoric should not be reduced to rhetorical figures. Figures are generally divided into four main categories: diction (e.g. anagram and alliteration), construction (e.g. chiasmus and anacoluthon), meaning (tropes, e.g. metaphor and metonymy) and thought (e.g. hyperbole and irony). The rhetorical figure is traditionally defined as a “reasoned change of meaning or of language vis-a-vis the ordinary and simple manner of expressing oneself.”7 Jean-Marie Klinkenberg (Klinkenberg 2000: 343) defines a rhetorical figure more precisely as “a dispositif consisting in the production of implicit meanings, so that the utterance is polyphonic”. In interactive and multimedia writing, the polyphonic dimension of the figure also relies on the pluricodal nature of the content.

I have identified rhetorical figures specific to interactive writing: figures of manipulation, meaning gestural manipulation (Bouchardon, 2014). It is a category on its own, along with figures of diction, construction, meaning and thought (Bouchardon & Heckman, 2012). Let us illustrate this point with the short digital fiction Don’t touch me.8 This work displays a photograph of a woman lying on a bed (see figure 11), as a voice - that of Annie Abrahams, the author - starts telling a story. The narrative is about a dream that Annie Abrahams had when she was a teenager. This dream can be interpreted as the sometimes painful transition from teenage to adulthood about a young woman exposed to the gaze and the desire of men. Being passive, looking and listening without using the mouse is not always easy for the interactor, often prompted to click compulsively. If the interactor rolls the cursor over the image, the image seems to resist the reader. Text immediately appears on the screen expressing the woman’s refusal (“don’t touch me”), the woman changes her physical position and the vocal tale immediately stops and restarts from the beginning. On the fourth attempt of a caress with the mouse, the window closes.

The story Don’t touch me has a vocal, visual (the woman displayed) and written-textual dimension (the three messages of refusal). It also has a gestural dimension: it is through the action of the user that the vocal narrative makes sense. This is an interactive story that is based on a play between interactivity and narrativity (Ensslin, 2012). Interactivity prevents narrativity insofar as the gesture of the user stops the narrative. The author also plays on the apparent incompatibility between narrativity and interactivity to teach the user to resist his desire to click, but also to apprehend differently the representations - especially online – of the female body. The vocal narrative can only be interpreted through the gesture of the user: it makes sense because it is interactive.

In the piece Don’t touch me, we can identify a gap between the expectations of the interactor when he or she moves the mouse cursor and the result obtained with this manipulation (until the final white screen). The caress on the picture of the woman with the mouse cursor only interrupts and then brutally stops the course of the piece, giving rise to a figure of manipulation that could be called a figure of interruption.

Numerous interactive digital fictions indeed play on the expectations of the reader by resorting to non-conventional couplings between the gesture and the result on screen, which can be analyzed in terms of figures. Let us now focus on an entire digital fiction. Loss of Grasp9 is an online interactive narrative in five different languages. In this creation, six scenes tell the story of a character who is losing grasp on his life. In the first scene, the reader unfolds the narrative by rolling over the sentences which appear on the screen. Each time a sentence is rolled over, a new sentence is displayed. But after a while, when the sentence “Everything escapes me” appears, the mouse cursor disappears. The reader can keep rolling over each sentence, but without the reference point of the mouse cursor. Through this “non-conventional media coupling” (Bouchardon, 2014), the reader experiences loss of grasp with his/her gestures.

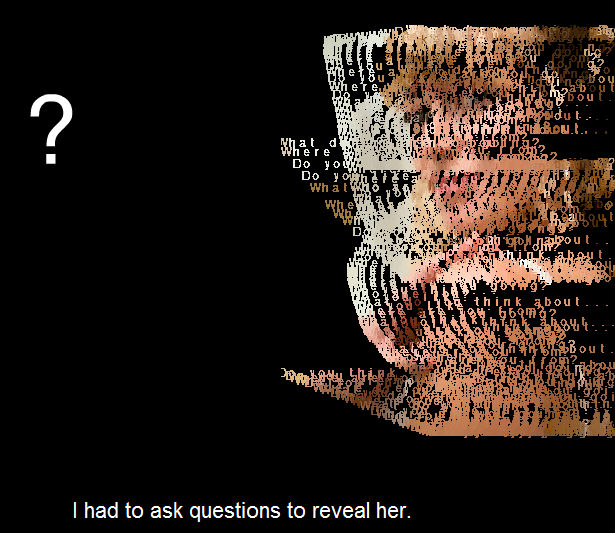

The second scene stages the meeting of the character with his future wife, 20 years earlier. While the character “ask[s] questions to reveal her”, the reader can discover the face of the woman by moving the mouse cursor. These movements leave trails of questions which progressively unveil her face. The questions themselves constitute the portrait of the woman (see figure 12).

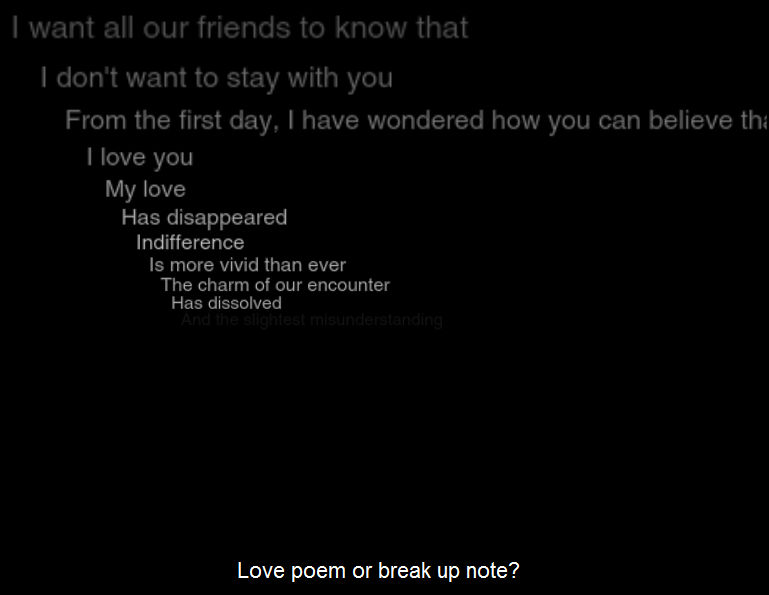

In the third scene, 20 years later, the character can’t seem to understand a note left by his wife: “love poem or break up note?” The reader can experience this double meaning with gestures. If he/she moves the mouse cursor to the right, the text will unfold as a love poem; if he/she moves the cursor to the left, the order of the lines is reversed and the text turns into a break up note (see figure 13).

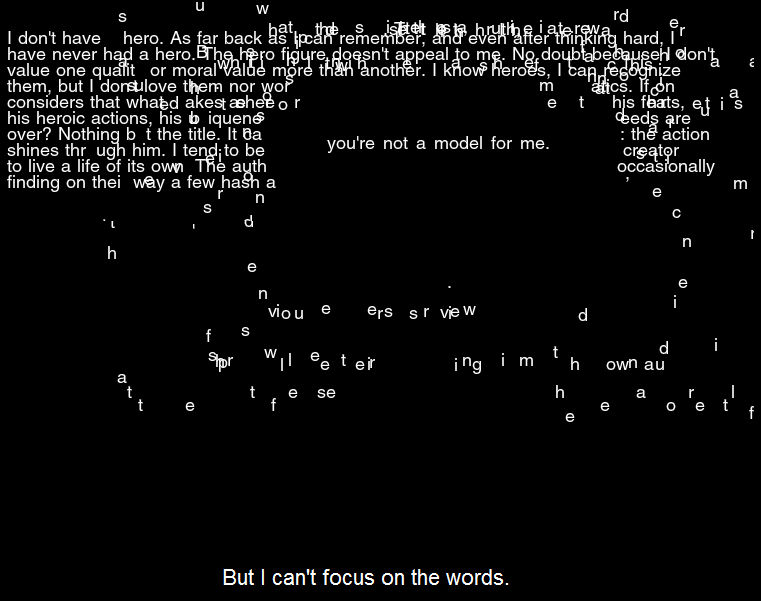

In the fourth scene, the character’s teenage son asks his father to read an essay he wrote on the notion of “hero”. But the character cannot focus on the words and “can only read between the lines”. If the reader clicks on the words of the essay, sentences appear – made up of letters from the text itself – such as:

I don’t love you. You don’t know me. We have nothing in common. I don’t want anything from you. You’re not a model for me. I want to make my own way. Soon I will leave.

Paradoxically, the gesture of focusing on the text makes it fall apart and lets an implicit meaning appear (see figure 14).

In the fifth scene, even the character’s own image seems to escape him. Via the webcam, the image of the reader appears on the screen. He/she can distort and manipulate it. The character/reader so “feel[s] manipulated”.

In the last scene, the character decides to take control again. A typing window is proposed to the reader, in which he/she can write. But whatever keys he/she types, the following text appears progressively.

I’m doing all I can to get a grip on my life again. I make choices. I control my emotions. The meaning of things. At last, I have a grasp…

Here again, the reader is confronted with a figure which relies on a gap between his/her expectations and the result of his/her manipulations on screen. Thus through his/her gestures and through various figures of manipulation – which could as a matter of fact appear as variations on a figure of loss of grasp – the reader experiences the character’s loss of grasp in an interactive way.

Conclusion

The examples analyzed above raise the question of the gesture and more largely of the engagement of the body in digital literature. Gestural manipulation is certainly inherent in writing and reading devices; however, the Digital results in a passage to the limit by introducing computation into the very principle of manipulation (Bachimont, 2008). What can happen when the user makes the gesture of typing a letter on the keyboard? Another letter may be displayed instead10, or the typed letter may leave the input field and fly away, or that gesture can generate a sound, run a query in a search engine, or even turn the computer off (all these examples are to be found in digital literature)… From this simple gesture, the realm of possibilities exceeds the anticipation inherent in the gesture. Because of the arbitrariness and opacity of computation, the Digital introduces a gap between the user’s expectations based on his/her gestures and the realm of possibilities offered.

The Digital makes it possible to defamiliarize the gestural experience inherent to reading and writing, to make it unfamiliar and even strange again. Defamiliarization is of course the project of many avant-gardes and literary approaches (and more generally, art approaches). But one could argue that there are particularities to the digital mode of defamiliarization. In literature, defamiliarization concerns the linguistic aspect. In digital literature, Roberto Simanowski claims that

“the concept of defamiliarization needs to be applied beyond the realm of linguistics to the entire cyber “language”, including the visual and acoustic material as well as the idiosyncratic features of digital media such as intermediality, interactivity, animation and hyperlink. A more general definition therefore characterizes the literary as the arranging of the material or the use of features in an uncommon fashion to undermine any automatic perception for the purpose of aesthetic perception” (Simanowski, 2010: 16).

Defamiliarization thus concerns not only the linguistic dimension, but also the iconic and sound dimensions, as well as the gestural dimension. However, there is one difficulty: as Simanowski rightfully asks, “how can we identify the “unusual” in a realm of expression not yet old enough (and growing too fast) to have established the “common”?” (Simanowski, 2010: 16). How can defamiliarization be identified in a system of expression that has not yet established familiar and common ground? It is undoubtedly through the question of gesturality that the experience of defamiliarization can be made explicit, insofar as a repertoire of gestures has begun to stabilize with digital devices (PC and tactile devices).

As said previously, with the Digital, the interactive gesture and the interactive gestural manipulation are defamiliarized thanks to the opacity of computation: the Digital can introduce a gap between the user’s expectations based on his/her gestures and the realm of possibilities offered. In interactive digital literature, defamiliarization is based on computation. In this sense, one could speak of a gesturality specific to the Digital, which is particularly well highlighted in digital literature.

The role played by computation, by digital programs and interfaces, must be taken into account to analyze gestural manipulations and to grasp their specificities. Hypothesizing that there is a gesturality specific to the Digital entails the necessity to sensitize and train users to the role of gesture in the construction of the meaning of a digital creation. It is indeed important to understand and analyze the semiotics and the rhetoric specific to these gestural manipulations when teaching digital literacy. Understanding gesturality through digital literature should be part of digital literacy teaching.

References

Aarseth, E. (1997). Cybertext, Perspective on Ergodic Literature. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press.

Bachimont, B. (2008). “Formal Signs and Numerical Computation: Between Intuitionism and Formalism. Critique of Computational Reason” in H. Schramm, L. Schwarte and J. Lazardzig (Eds.), Theatrum Scientiarum: Instruments in Art and Science. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter Verlag, 362-382.

Bouchardon, S. (2014). “Figures of gestural manipulation in digital fictions” in Bell, A., Ensslin, A., Rustad, H. (dir.) Analyzing digital fiction. London: Routledge, 159-175.

Bouchardon, S., Heckman, D. (2012). “Digital Manipulability and Digital Literature”, Electronic Book Review, ISSN 1553 1139, August 2012, http://www.electronicbookreview.com/thread/electropoetics/heuristic

Ensslin, A. (2012). “Computer Gaming”, in Bray, J., Gibbons, A. and McHale, B. (eds.), The Routledge Companion to Experimental Literature. London: Routledge.

Hayles, N. K. (2008). Electronic Literature: New Horizons for the Literary. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press.

Jeanneret, Y. (2000). Y a-t-il vraiment des technologies de l’information? Paris: Editions universitaires du Septentrion.

Klinkenberg, J.-M. (2000) Précis de sémiotique générale. Brussels: De Boeck.

Simanowski, R. (2010). “Reading Digital Literature” in Simanowski, R. Schäfer, J. and Gendolla, P. (eds). Reading Moving Letters. Digital Literature in Research and Teaching. Bielefeld: Transcript.

- Google Play: https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=com.tx.agir

- App Store: https://appsto.re/cn/WDN8fb.i

Footnotes

-

Digital or Electronic Literature: “The term refers to works with important literary aspects that take advantage of the capabilities and contexts provided by the stand-alone or networked computer” (Electronic Literature Organization, http://www.eliterature.org/about. ↩

-

The use of the capitalized noun “the Digital” (instead of “digital media” or “digital technology”) refers to the French expression “le numérique”, which designates both a technical and a cultural reality. “The Digital” refers to the notion of digital milieu: the stake consists in considering “the Digital” not only as a means, but as a milieu, namely that which surrounds us and exists between us, that which acts as a stimulus for our actions and pushes us to make transformations through a permanent co-constitutive relationship. The notion of “milieu” is borrowed from Gilbert Simondon, who incessantly strove to reconcile culture and technology. ↩

-

http://i-trace.fr/separation/index.php Video capture of the interactions: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OdQEOF3misE ↩

-

DO IT (2016) is an interactive app. freely available on: ↩

-

Video captures of the interactions : https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=u6UOq-j_ZJ4. ↩

-

Quintilian, De institutione oratoria, IX, 1, 11-13. ↩

-

Abrahams Annie (2003). Ne me touchez pas/Don’t touch me, http://www.bram.org/toucher/index.htm. ↩

-

Bouchardon Serge and Volckaert Vincent (2010). Loss of Grasp, http://lossofgrasp.com. This creation won the New Media Writing Prize 2011: http://newmediawritingprize.co.uk/past-winners/.It has been exhibited at ICIDS 2016 in Los Angeles. ↩

-

Cf. the last scene of Loss of Grasp: http://www.lossofgrasp.com/ ↩

Cite this article

Bouchardon, Serge. "Towards Gestural Specificity in Digital Literature" Electronic Book Review, 2 December 2018, https://doi.org/10.7273/chma-0q31